6.5 Fractures: Bone Repair

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

Explain how bone repairs itself after a fracture

- Differentiate among the different types of fractures

- Describe the steps involved in bone repair

A fracture is a broken bone. It will heal whether or not a physician resets (places) it in its anatomical position. If the bone is not reset correctly, the healing process will rebuild new bone but keep the bone in its deformed position.

When a broken bone is manipulated and set into its natural position without surgery, the procedure is called a closed reduction. Open reduction requires surgery to expose the fracture and reset the bone. While some fractures can be minor, others are quite severe and result in grave complications. For example, a fractured diaphysis of the femur has the potential to release fat globules into the bloodstream. These can become lodged in the capillary beds of the lungs, leading to respiratory distress and if not treated quickly, death (this is called a pulmonary embolism).

Types of Fractures

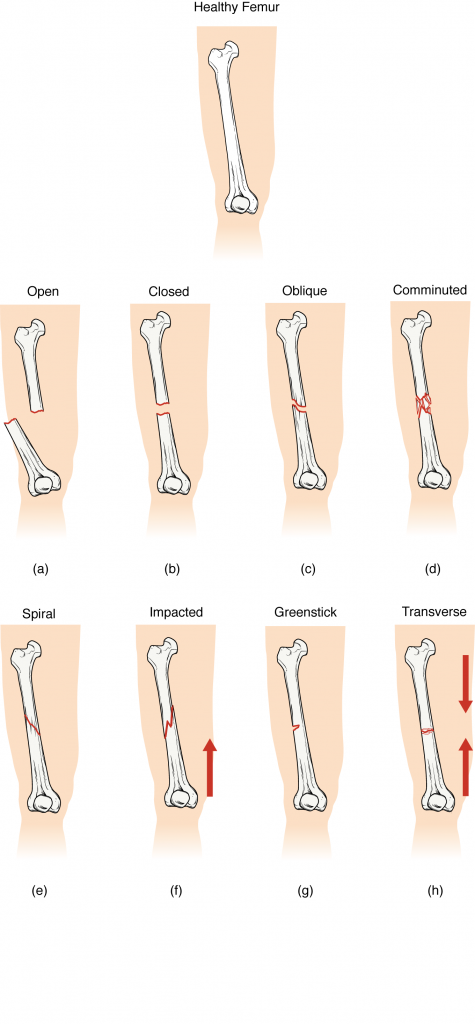

Fractures are classified by their complexity, location, and other features (Figure 6.5.1). Table 6.4 outlines common types of fractures. Some fractures may be described using more than one term because it may have the features of more than one type (e.g., an open transverse fracture).

| Types of Fractures (Table 6.4) | |

|---|---|

| Type of fracture | Description |

| Transverse | Occurs straight across the long axis of the bone |

| Oblique | Occurs at an angle that is not 90 degrees |

| Spiral | Bone segments are pulled apart as a result of a twisting motion |

| Comminuted | Several breaks result in many small pieces between two large segments |

| Impacted | One fragment is driven into the other, usually as a result of compression |

| Greenstick | A partial fracture in which only one side of the bone is broken, often occurs in the young |

| Type of Fracture | Description |

|---|---|

| Open (or compound) | A fracture in which at least one end of the broken bone tears through the skin; carries a high risk of infection |

| Closed (or simple) | A fracture in which the skin remains intact |

Bone Repair

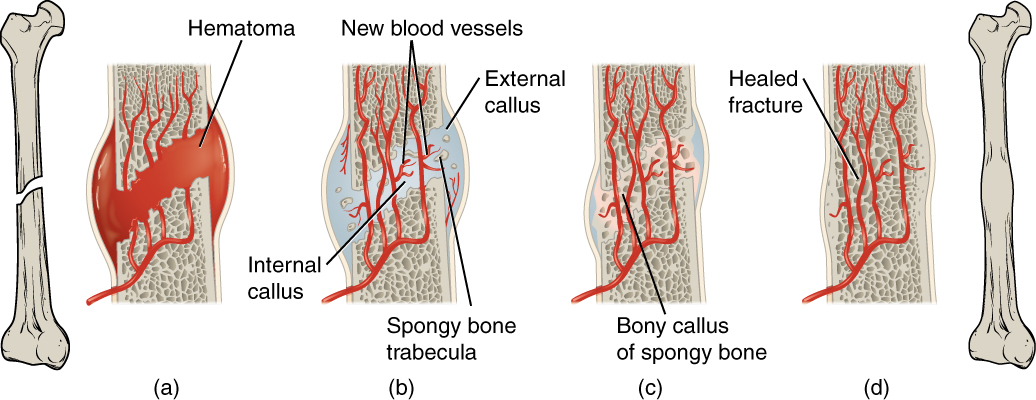

Depending on the type, severity of the fracture and distance between bone fragments, bones may heal directly by building new bone onto the fracture site (direct bone healing or contact healing) or may heal in a process like endochondral bone formation (indirect bone healing). Direct bone healing is essentially bone remodeling in which osteoblasts and osteoclasts unite broken structures. With indirect bone healing the process is more complicated and similar to endochondral bone formation in which broken bones form cartilaginous patches before regrowing new bone. In this process, blood released from broken or torn vessels in the periosteum, osteons, and/or medullary cavity clots into a fracture hematoma (Figure 6.5.2a). Though broken vessels promote an increase in nutrient delivery to the site of vessel injury (see inflammation process in blood vessel chapter), the disruption of blood flow to the bone results in the death of bone cells around the fracture.

Within about 48 hours after the fracture, stem cells from the endosteum of the bone differentiate into chondrocytes which then secrete a fibrocartilaginous matrix between the two ends of the broken bone; gradually over several days to weeks, this matrix unites the opposite ends of the fracture into an internal callus (plural = calli or calluses). Additionally, the periosteal chondrocytes form and working with osteoblasts, create an external callus of cartilage and bone, respectively, around the outside of the break (Figure 6.5.2b). Together, these temporary soft calluses stabilize the fracture.

Over the next several weeks, osteoclasts resorb the dead bone while osteogenic cells become active, divide, and differentiate into more osteoblasts. The cartilage in the calluses is replaced by trabecular bone via endochondral ossification (destruction of cartilage and replacement by bone) (Figure 6.5.2c). This new bony callus is also called the hard callus.

Over several more weeks or months, compact bone replaces spongy bone at the outer margins of the fracture and the bone is remodeled in response to strain (Figure 6.5.2d). Once healing and remodeling are complete a slight swelling may remain on the outer surface of the bone, but quite often, no external evidence of the fracture remains. This is why bone is said to be a regenerative tissue that can completely replace itself without scars.

External Website

Visit this website to review different types of fractures and then take a short self-assessment quiz.

Section Review

Fractures are classified by their complexity, location, and other features. Common types of fractures are transverse, oblique, spiral, comminuted, impacted, greenstick; they may also be classified as open (or compound), and closed (or simple). During indirect bone healing, fracture repair begins with the formation of a hematoma, followed by cartilaginous internal and external calluses. Osteoclasts resorb dead bone, while osteoblasts create new bone that replaces the cartilage in the calluses. Calluses eventually unite, and bone remodeling occurs to complete the healing process.

Review Question

Critical Thinking Questions

1. What is the difference between closed reduction and open reduction? In what type of fracture would closed reduction most likely occur? In what type of fracture would open reduction most likely occur?

2. In terms of origin, composition and cells involved, what are the differences between an internal callus and an external callus?

Glossary

- closed reduction

- manual manipulation of a broken bone to set it into its natural position without surgery

- external callus

- collar of cartilage and bone that forms around the outside of a fracture

- fracture

- broken bone

- fracture hematoma

- blood clot that forms at the site of a broken bone due to broken blood vessels

- internal callus

- fibrocartilaginous matrix, in the endosteal region, between the two ends of a broken bone

- open reduction

- surgical exposure of a bone to reset a fracture

Solutions

Answers for Critical Thinking Questions

- In closed reduction, the broken ends of a fractured bone can be reset without surgery. Open reduction requires surgery to return the broken ends of the bone to their correct anatomical position. A partial fracture would likely require closed reduction. A compound fracture would require open reduction.

- The internal callus is produced by cells in the endosteum and is composed of a fibrocartilaginous matrix. The external callus is produced by cells in the periosteum and consists of hyaline cartilage and bone. Both types are formed by stem cells that differentiate into chondroblasts (chondrocytes), but in different locations.

This work, Anatomy & Physiology, is adapted from Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax, licensed under CC BY. This edition, with revised content and artwork, is licensed under CC BY-SA except where otherwise noted.

Images, from Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax, are licensed under CC BY except where otherwise noted.

Access the original for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction.