24.7 Nutrition and Diet

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain how different foods can affect metabolism

- Describe a healthy diet, as recommended by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA)

- List reasons why vitamins and minerals are critical to a healthy diet

The carbohydrates, lipids, and proteins in the foods you eat are used for energy to power molecular, cellular, and organ system activities. Importantly, the energy is stored primarily as fats. The quantity and quality of food that is ingested, digested, and absorbed affects the amount of fat that is stored as excess calories. Diet—both what you eat and how much you eat—has a dramatic impact on your health. Eating too much or too little food can lead to serious medical issues, including cardiovascular disease, cancer, anorexia, and diabetes, among others. Combine an unhealthy diet with unhealthy environmental conditions, such as smoking, and the potential medical complications increase significantly.

Food and Metabolism

The amount of energy that is needed or ingested per day is measured in calories. The nutritional Calorie (C) is the amount of heat it takes to raise 1 kg (1000 g) of water by 1 °C. This is different from the calorie (c) used in the physical sciences, which is the amount of heat it takes to raise 1 g of water by 1 °C. When we refer to “calorie,” we are referring to the nutritional Calorie.

On average, a person needs 1500 to 2000 calories per day to sustain (or carry out) daily activities. The total number of calories needed by one person is dependent on their body mass, age, height, gender, activity level, and the amount of exercise per day. If exercise is regular part of one’s day, more calories are required. As a rule, people underestimate the number of calories ingested and overestimate the amount they burn through exercise. This can lead to ingestion of too many calories per day. The accumulation of an extra 3500 calories adds one pound of weight. If an excess of 200 calories per day is ingested, one extra pound of body weight will be gained every 18 days. At that rate, an extra 20 pounds can be gained over the course of a year. Of course, this increase in calories could be offset by increased exercise. Running or jogging one mile burns almost 100 calories.

The type of food ingested also affects the body’s metabolic rate. Processing of carbohydrates requires less energy than processing of proteins. In fact, the breakdown of carbohydrates requires the least amount of energy, whereas the processing of proteins demands the most energy. In general, the amount of calories ingested and the amount of calories burned determines the overall weight. To lose weight, the number of calories burned per day must exceed the number ingested. Calories are in almost everything you ingest, so when considering calorie intake, beverages must also be considered.

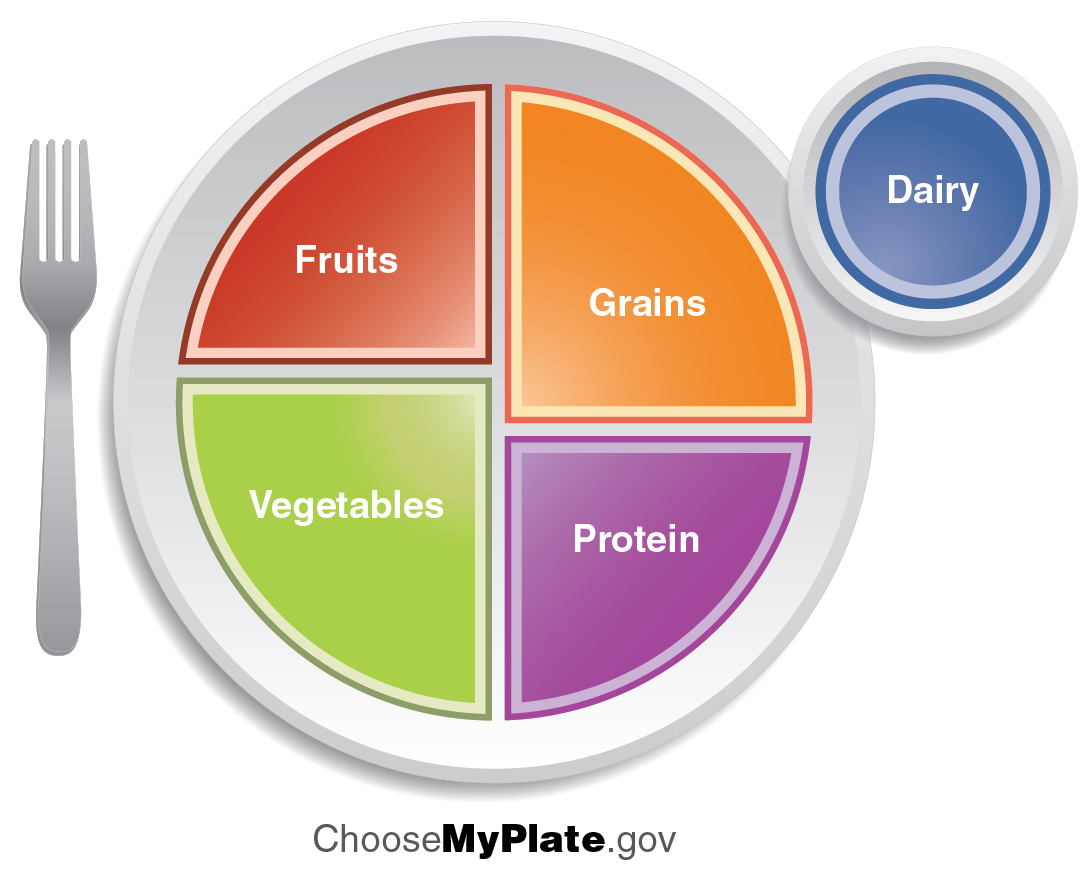

To help provide guidelines regarding the types and quantities of food that should be eaten every day, the USDA has updated their food guidelines from MyPyramid to MyPlate. They have put the recommended elements of a healthy meal into the context of a place setting of food. MyPlate categorizes food into the standard six food groups: fruits, vegetables, grains, protein foods, dairy, and oils. The accompanying website gives clear recommendations regarding quantity and type of each food that you should consume each day, as well as identifying which foods belong in each category. The accompanying graphic (Figure 24.7.1) gives a clear visual with general recommendations for a healthy and balanced meal. The guidelines recommend to “Make half your plate fruits and vegetables.” The other half is grains and protein, with a slightly higher quantity of grains than protein. Dairy products are represented by a drink, but the quantity can be applied to other dairy products as well.

ChooseMyPlate.gov provides extensive online resources for planning a healthy diet and lifestyle, including offering weight management tips and recommendations for physical activity. It also includes the SuperTracker, a web-based application to help you analyze your own diet and physical activity.

Everyday Connections – Metabolism and Obesity

Obesity in the United States is epidemic. The rate of obesity has been steadily rising since the 1980s. In the 1990s, most states reported that less than 10 percent of their populations was obese, and the state with the highest rate reported that only 15 percent of their population was considered obese. By 2010, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that nearly 36 percent of adults over 20 years old were obese and an additional 33 percent were overweight, leaving only about 30 percent of the population at a healthy weight. These studies find the highest levels of obesity are concentrated in the southern states. They also find the level of childhood obesity is rising.

Obesity is defined by the body mass index (BMI), which is a measure of an individual’s weight-to-height ratio. The normal, or healthy, BMI range is between 18 and 24.9 kg/m2. Overweight is defined as a BMI of 25 to 29.9 kg/m2, and obesity is considered to be a BMI greater than 30 kg/m2. Obesity can arise from a number of factors, including overeating, poor diet, sedentary lifestyle, limited sleep, genetic factors, and even diseases or drugs. Severe obesity (morbid obesity) or long-term obesity can result in serious medical conditions, including coronary heart disease; type 2 diabetes; endometrial, breast, or colon cancer; hypertension (high blood pressure); dyslipidemia (high cholesterol or elevated triglycerides); stroke; liver disease; gall bladder disease; sleep apnea or respiratory diseases; osteoarthritis; and infertility. Research has shown that losing weight can help reduce or reverse the complications associated with these conditions.

Vitamins

Vitamins are organic compounds found in foods and are a necessary part of the biochemical reactions in the body. They are involved in a number of processes, including mineral and bone metabolism, and cell and tissue growth, and they act as cofactors for energy metabolism. The B vitamins play the largest role of any vitamins in metabolism (Table 24.3 and Table 24.4).

You get most of your vitamins through your diet, although some can be formed from the precursors absorbed during digestion. For example, the body synthesizes vitamin A from the β-carotene in orange vegetables like carrots and sweet potatoes. Vitamins are either fat-soluble or water-soluble. Fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E, and K, are absorbed through the intestinal tract with lipids in chylomicrons. Vitamin D is also synthesized in the skin through exposure to sunlight. Because they are carried in lipids, fat-soluble vitamins can accumulate in the lipids stored in the body. If excess vitamins are retained in the lipid stores in the body, hypervitaminosis can result.

Water-soluble vitamins, including the eight B vitamins and vitamin C, are absorbed with water in the gastrointestinal tract. These vitamins move easily through bodily fluids, which are water based, so they are not stored in the body. Excess water-soluble vitamins are usually excreted in the urine. Therefore, hypervitaminosis of water-soluble vitamins rarely occurs, except with an excess of vitamin supplements.

| Fat-soluble Vitamins (Table 24.3) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin and alternative name | Sources | Recommended daily allowance | Function | Problems associated with deficiency |

| A

retinal or β-carotene

|

Yellow and orange fruits and vegetables, dark green leafy vegetables, eggs, milk, liver | 700–900 µg | Eye and bone development, immune function | Night blindness, epithelial changes, immune system deficiency |

| D

cholecalciferol

|

Dairy products, egg yolks; also synthesized in the skin from exposure to sunlight | 5–15 µg | Aids in calcium absorption, promoting bone growth | Rickets, bone pain, muscle weakness, increased risk of death from cardiovascular disease, cognitive impairment, asthma in children, cancer |

| E

tocopherols

|

Seeds, nuts, vegetable oils, avocados, wheat germ | 15 mg | Antioxidant | Anemia |

| K

phylloquinone

|

Dark green leafy vegetables, broccoli, Brussels sprouts, cabbage | 90–120 µg | Blood clotting, bone health | Hemorrhagic disease of newborn in infants; uncommon in adults |

| Water-soluble Vitamins (Table 24.4) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin and alternative name | Sources | Recommended daily allowance | Function | Problems associated with deficiency |

| B1

thiamine

|

Whole grains, enriched bread and cereals, milk, meat | 1.1–1.2 mg | Carbohydrate metabolism | Beriberi, Wernicke-Korsikoff syndrome |

| B2

riboflavin

|

Brewer’s yeast, almonds, milk, organ meats, legumes, enriched breads and cereals, broccoli, asparagus | 1.1–1.3 mg | Synthesis of FAD for metabolism, production of red blood cells | Fatigue, slowed growth, digestive problems, light sensitivity, epithelial problems like cracks in the corners of the mouth |

| B3

niacin

|

Meat, fish, poultry, enriched breads and cereals, peanuts | 14–16 mg | Synthesis of NAD for metabolism, nerve function, cholesterol production | Cracked, scaly skin; dementia; diarrhea; also known as pellagra |

| B5

pantothenic acid

|

Meat, poultry, potatoes, oats, enriched breads and cereals, tomatoes | 5 mg | Synthesis of coenzyme A in fatty acid metabolism | Rare: symptoms may include fatigue, insomnia, depression, irritability |

| B6

pyridoxine

|

Potatoes, bananas, beans, seeds, nuts, meat, poultry, fish, eggs, dark green leafy vegetables, soy, organ meats | 1.3–1.5 mg | Sodium and potassium balance, red blood cell synthesis, protein metabolism | Confusion, irritability, depression, mouth and tongue sores |

| B7

biotin

|

Liver, fruits, meats | 30 µg | Cell growth, metabolism of fatty acids, production of blood cells | Rare in developed countries; symptoms include dermatitis, hair loss, loss of muscular coordination |

| B9

folic acid

|

Liver, legumes, dark green leafy vegetables, enriched breads and cereals, citrus fruits | 400 µg | DNA/protein synthesis | Poor growth, gingivitis, appetite loss, shortness of breath, gastrointestinal problems, mental deficits |

| B12

cyanocobalamin

|

Fish, meat, poultry, dairy products, eggs | 2.4 µg | Fatty acid oxidation, nerve cell function, red blood cell production | Pernicious anemia, leading to nerve cell damage |

| C

ascorbic acid

|

Citrus fruits, red berries, peppers, tomatoes, broccoli, dark green leafy vegetables | 75–90 mg | Necessary to produce collagen for formation of connective tissue and teeth, and for wound healing | Dry hair, gingivitis, bleeding gums, dry and scaly skin, slow wound healing, easy bruising, compromised immunity; can lead to scurvy |

Minerals

Minerals in food are inorganic compounds that work with other nutrients to ensure the body functions properly. Minerals cannot be made in the body; they come from the diet. The amount of minerals in the body is small—only 4 percent of the total body mass—and most of that consists of the minerals that the body requires in moderate quantities: potassium, sodium, calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, and chloride.

The most common minerals in the body are calcium and phosphorous, both of which are stored in the skeleton and necessary for the hardening of bones. Most minerals are ionized, and their ionic forms are used in physiological processes throughout the body. Sodium and chloride ions are electrolytes in the blood and extracellular tissues, and iron ions are critical to the formation of hemoglobin. Many minerals are used as cofactors and coenzymes in metabolic processes. There are additional trace minerals that are still important to the body’s functions, but their required quantities are much lower.

Like vitamins, minerals can be consumed in toxic quantities (although it is rare). A healthy diet includes most of the minerals your body requires, so supplements and processed foods can add potentially toxic levels of minerals. Table 24.5 and Table 24.6 provide a summary of minerals and their function in the body.

| Major Minerals (Table 24.5) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mineral | Sources | Recommended daily allowance | Function | Problems associated with deficiency |

| Potassium | Meats, some fish, fruits, vegetables, legumes, dairy products | 4700 mg | Nerve and muscle function; acts as an electrolyte | Hypokalemia: weakness, fatigue, muscle cramping, gastrointestinal problems, cardiac problems |

| Sodium | Table salt, milk, beets, celery, processed foods | 2300 mg | Blood pressure, blood volume, muscle and nerve function | Rare |

| Calcium | Dairy products, dark green leafy vegetables, blackstrap molasses, nuts, brewer’s yeast, some fish | 1000 mg | Bone structure and health; nerve and muscle functions, especially cardiac function; blood cloting | Slow growth, weak and brittle bones |

| Phosphorous | Meat, milk | 700 mg | Bone formation, metabolism, ATP production | Rare |

| Magnesium | Whole grains, nuts, leafy green vegetables | 310–420 mg | Enzyme activation, production of energy, regulation of other nutrients; enzyme cofactor (essential for metabolism) | Agitation, anxiety, sleep problems, nausea and vomiting, abnormal heart rhythms, low blood pressure, muscular problems |

| Chloride | Most foods, salt, vegetables, especially seaweed, tomatoes, lettuce, celery, olives | 2300 mg | Balance of body fluids, digestion | Loss of appetite, muscle cramps |

| Trace Minerals (Table 24.6) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mineral | Sources | Recommended daily allowance | Function | Problems associated with deficiency |

| Iron | Meat, poultry, fish, shellfish, legumes, nuts, seeds, whole grains, dark leafy green vegetables | 8–18 mg | Transport of oxygen in blood, production of ATP | Anemia, weakness, fatigue |

| Zinc | Meat, fish, poultry, cheese, shellfish | 8–11 mg | Immunity, reproduction, growth, blood clotting, insulin and thyroid function | Loss of appetite, poor growth, weight loss, skin problems, hair loss, vision problems, lack of taste or smell |

| Copper | Seafood, organ meats, nuts, legumes, chocolate, enriched breads and cereals, some fruits and vegetables | 900 µg | Red blood cell production, nerve and immune system function, collagen formation, acts as an antioxidant; enzyme cofactor (essential for metabolism) | Anemia, low body temperature, bone fractures, low white blood cell concentration, irregular heartbeat, thyroid problems |

| Iodine | Fish, shellfish, garlic, lima beans, sesame seeds, soybeans, dark leafy green vegetables | 150 µg | Thyroid function | Hypothyroidism: fatigue, weight gain, dry skin, temperature sensitivity |

| Sulfur | Eggs, meat, poultry, fish, legumes | None | Component of amino acids; enzyme cofactor | Protein deficiency |

| Fluoride | Fluoridated water | 3–4 mg | Maintenance of bone and tooth structure | Increased cavities, weak bones and teeth |

| Manganese | Nuts, seeds, whole grains, legumes | 1.8–2.3 mg | Formation of connective tissue and bones, blood clotting, sex hormone development, metabolism, brain and nerve function; enzyme cofactor (essential for metabolism) | Infertility, bone malformation, weakness, seizures |

| Cobalt | Fish, nuts, leafy green vegetables, whole grains | None | Component of B12 | None |

| Selenium | Brewer’s yeast, wheat germ, liver, butter, fish, shellfish, whole grains | 55 µg | Antioxidant, thyroid function, immune system function | Muscle pain |

| Chromium | Whole grains, lean meats, cheese, black pepper, thyme, brewer’s yeast | 25–35 µg | Insulin function | High blood sugar, triglyceride, and cholesterol levels |

| Molybdenum | Legumes, whole grains, nuts | 45 µg | Cofactor for enzymes | Rare |

Chapter Review

Nutrition and diet affect your metabolism. More energy is required to break down fats and proteins than carbohydrates; however, all excess calories that are ingested will be stored as fat in the body. On average, a person requires 1500 to 2000 calories for normal daily activity, although routine exercise will increase that amount. If you ingest more than that, the remainder is stored for later use. Conversely, if you ingest less than that, the energy stores in your body will be depleted. Both the quantity and quality of the food you eat affect your metabolism and can affect your overall health. Eating too much or too little can result in serious medical conditions, including cardiovascular disease, cancer, and diabetes.

Vitamins and minerals are essential parts of the diet. They are needed for the proper function of metabolic pathways in the body. Vitamins are not stored in the body, so they must be obtained from the diet or synthesized from precursors available in the diet. Minerals are also obtained from the diet, but they are also stored, primarily in skeletal tissues.

Review Questions

Critical Thinking Questions

1. Weight loss and weight gain are complex processes. What are some of the main factors that influence weight gain in people?

2. Some low-fat or non-fat foods contain a large amount of sugar to replace the fat content of the food. Discuss how this leads to increased fat in the body (and weight gain) even though the item is non-fat.

Glossary

- body mass index (BMI)

- relative amount of body weight compared to the overall height; a BMI ranging from 18–24.9 is considered normal weight, 25–29.9 is considered overweight, and greater than 30 is considered obese

- calorie

- amount of heat it takes to raise 1 kg (1000 g) of water by 1 °C

- minerals

- inorganic compounds required by the body to ensure proper function of the body

- vitamins

- organic compounds required by the body to perform biochemical reactions like metabolism and bone, cell, and tissue growth

Solutions

Answers for Critical Thinking Questions

- Factors that influence weight gain are food intake (both quantity and quality), environmental factors, height, exercise level, some drugs or disease states, and genes.

- Although these foods technically do not have fat added, many times a significant amount of sugar is added to sweeten the food and make it taste better. These foods are non-fat; however, they can lead to significant fat storage or weight gain because the excess sugar is broken down into pyruvate, but overloads the Krebs cycle. When this happens, the sugar is converted into fat through lipogenesis and stored in adipose tissues.

This work, Anatomy & Physiology, is adapted from Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax, licensed under CC BY. This edition, with revised content and artwork, is licensed under CC BY-SA except where otherwise noted.

Images, from Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax, are licensed under CC BY except where otherwise noted.

Access the original for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction.