6.3 Bone Structure

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Identify the gross anatomical features of a bone

- Define and list examples of bone markings

- Describe the histology of bone tissue, including the function of bone cells and matrix

- Compare and contrast compact and spongy bone

- Identify the structures that compose compact and spongy bone

- Describe how bones are nourished and innervated

Bone tissue (osseous tissue) differs greatly from other tissues in the body. Bone is hard and many of its functions depend on that characteristic hardness. Later discussions in this chapter will show that bone is also dynamic in that its shape adjusts to accommodate stresses. This section will examine the gross anatomy of bone first and then move on to its histology.

Gross Anatomy of Bones

A long bone has two main regions: the diaphysis and the epiphysis (Figure 6.3.1). The diaphysis is the hollow, tubular shaft that runs between the proximal and distal ends of the bone. Inside the diaphysis is the medullary cavity, which is filled with yellow bone marrow in an adult. The outer walls of the diaphysis (cortex, cortical bone)are composed of dense and hard compact bone, a form of osseous tissue.

The wider section at each end of the bone is called the epiphysis (plural = epiphyses), which is filled internally with spongy bone, another type of osseous tissue. Red bone marrow fills the spaces between the spongy bone in some long bones. Each epiphysis meets the diaphysis at the metaphysis. During growth, the metaphysis contains the epiphyseal plate, the site of long bone elongation described later in the chapter. When the bone stops growing in early adulthood (approximately 18–21 years), the epiphyseal plate becomes an epiphyseal line seen in the figure.

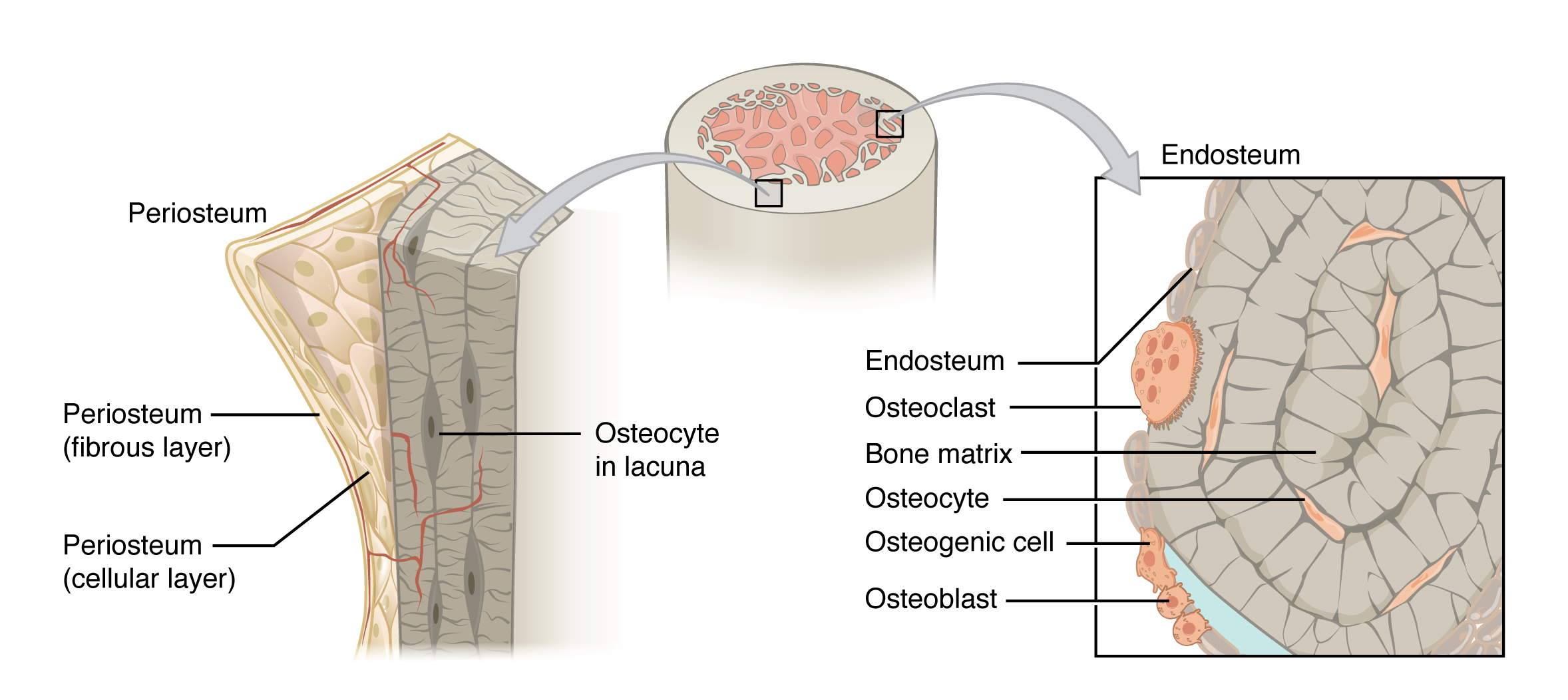

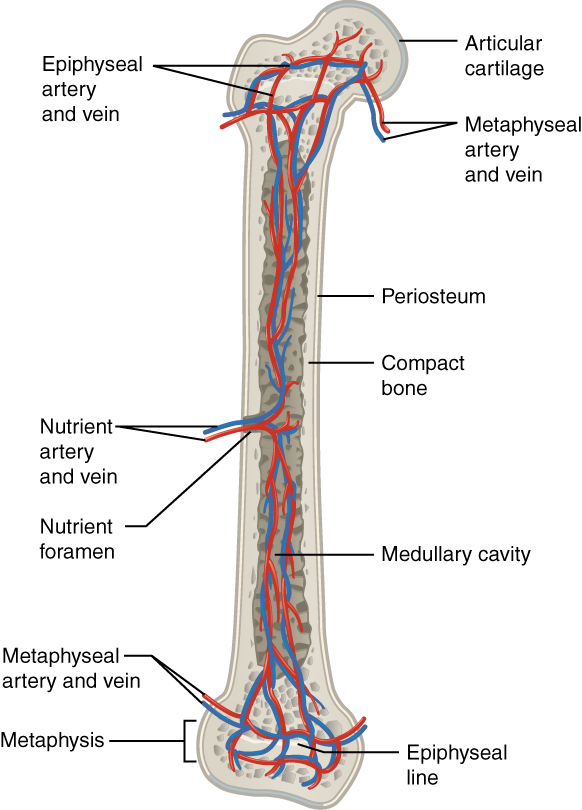

Lining the inside of the bone adjacent to the medullary cavity is a layer of bone cells called the endosteum (endo- = “inside”; osteo- = “bone”). These bone cells (described later) cause the bone to grow, repair, and remodel throughout life. On the outside of bones there is another layer of cells that grow, repair and remodel bone as well. These cells are part of the outer double layered structure called the periosteum (peri– = “around” or “surrounding”). The cellular layer is adjacent to the cortical bone and is covered by an outer fibrous layer of dense irregular connective tissue (see Figure 6.3.4). The periosteum also contains blood vessels, nerves, and lymphatic vessels that nourish compact bone. Tendons and ligaments attach to bones at the periosteum. The periosteum covers the entire outer surface except where the epiphyses meet other bones to form joints (Figure 6.3.2). In this region, the epiphyses are covered with articular cartilage, a thin layer of hyaline cartilage that reduces friction and acts as a shock absorber.

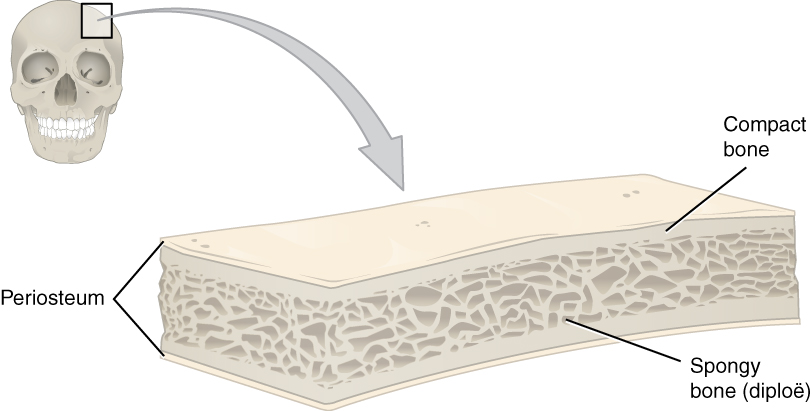

Flat bones, like those of the cranium, consist of a layer of diploë (spongy bone), covered on either side by a layer of compact bone (Figure 6.3.3). The two layers of compact bone and the interior spongy bone work together to protect the internal organs. If the outer layer of a cranial bone fractures, the brain is still protected by the intact inner layer.

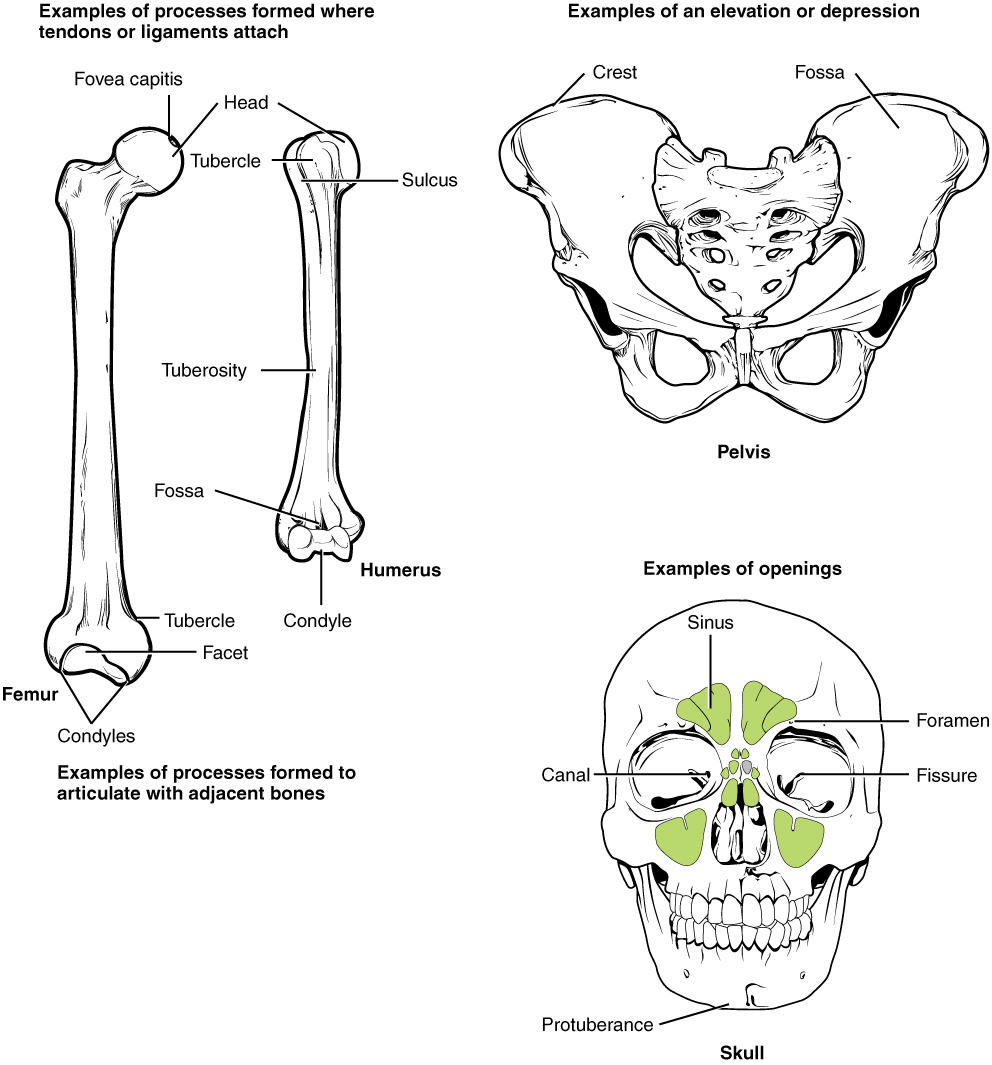

Bone Markings

The surface features of bones vary considerably, depending on the function and location in the body. Table 6.2 describes the bone markings, which are illustrated in (Figure 6.3.4). There are three general classes of bone markings: (1) articulations, (2) projections, and (3) holes. As the name implies, an articulation is where two bone surfaces come together (articulus = “joint”). These surfaces tend to conform to one another, such as one being rounded and the other cupped, to facilitate the function of the articulation. A projection is an area of a bone that projects above the surface of the bone. These are the attachment points for tendons and ligaments. In general, their size and shape is an indication of the forces exerted through the attachment to the bone. A hole is an opening or groove in the bone that allows blood vessels and nerves to enter the bone. As with the other markings, their size and shape reflect the size of the vessels and nerves that penetrate the bone at these points.

| Marking | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Articulations | Where two bones meet | Knee joint |

| Head | Prominent rounded surface | Head of femur |

| Facet | Flat surface | Vertebrae |

| Condyle | Rounded surface | Occipital condyles |

| Projections | Raised markings | Spinous process of the vertebrae |

| Protuberance | Protruding | Chin |

| Process | Prominence feature | Transverse process of vertebra |

| Spine | Sharp process | Ischial spine |

| Tubercle | Small, rounded process | Tubercle of humerus |

| Tuberosity | Rough surface | Deltoid tuberosity |

| Line | Slight, elongated ridge | Temporal lines of the parietal bones |

| Crest | Ridge | Iliac crest |

| Holes | Holes and depressions | Foramen (holes through which blood vessels can pass through) |

| Fossa | Elongated basin | Mandibular fossa |

| Fovea | Small pit | Fovea capitis on the head of the femur |

| Sulcus | Groove | Sigmoid sulcus of the temporal bones |

| Canal | Passage in bone | Auditory canal |

| Fissure | Slit through bone | Auricular fissure |

| Foramen | Hole through bone | Foramen magnum in the occipital bone |

| Meatus | Opening into canal | External auditory meatus |

| Sinus | Air-filled space in bone | Nasal sinus |

Osseous Tissue: Bone Matrix and Cells

Bone Matrix

Bone Cells

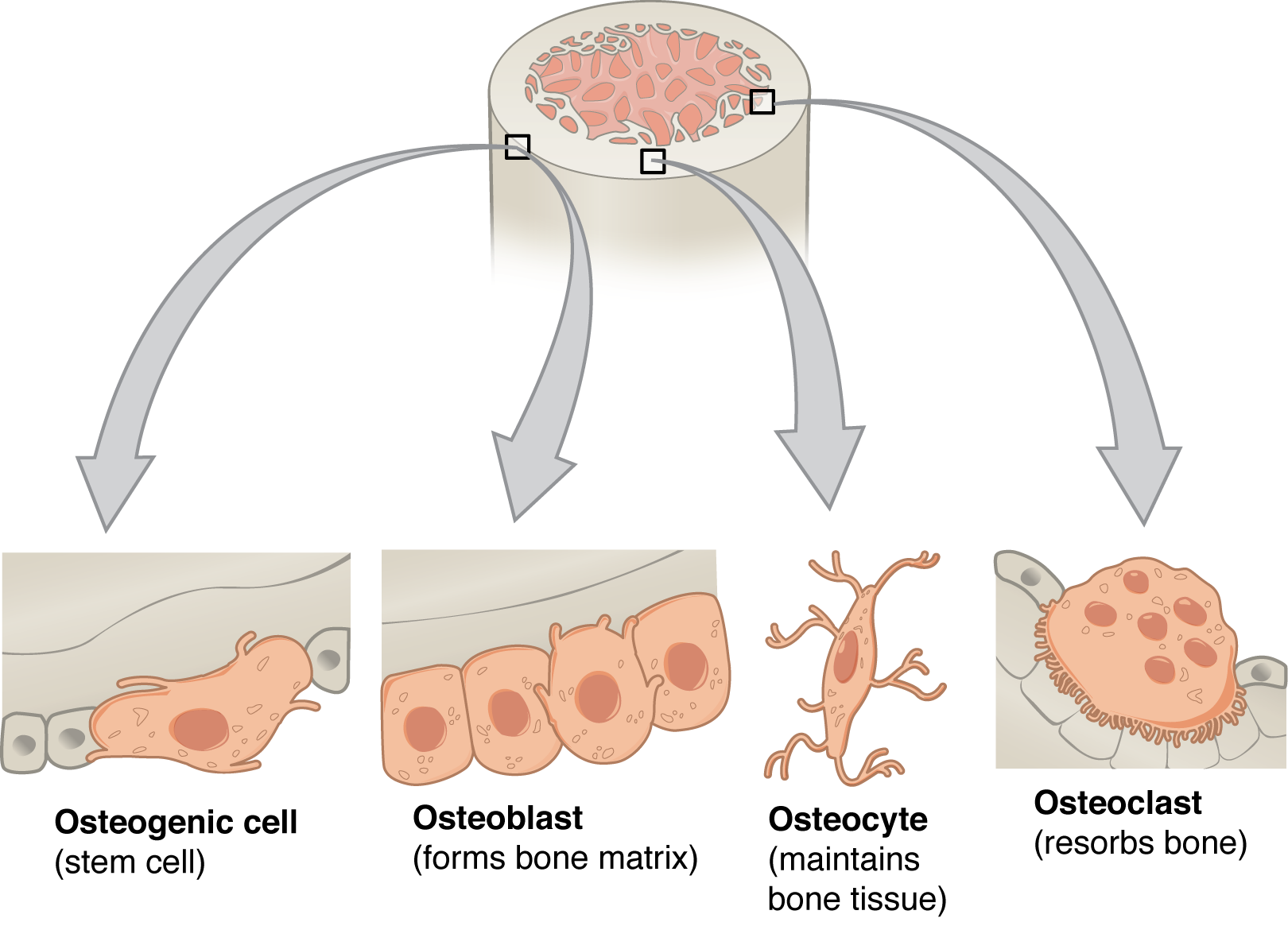

Although bone cells compose less than 2% of the bone mass, they are crucial to the function of bones. Four types of cells are found within bone tissue: osteoblasts, osteocytes, osteogenic cells, and osteoclasts (Figure 6.3.6).

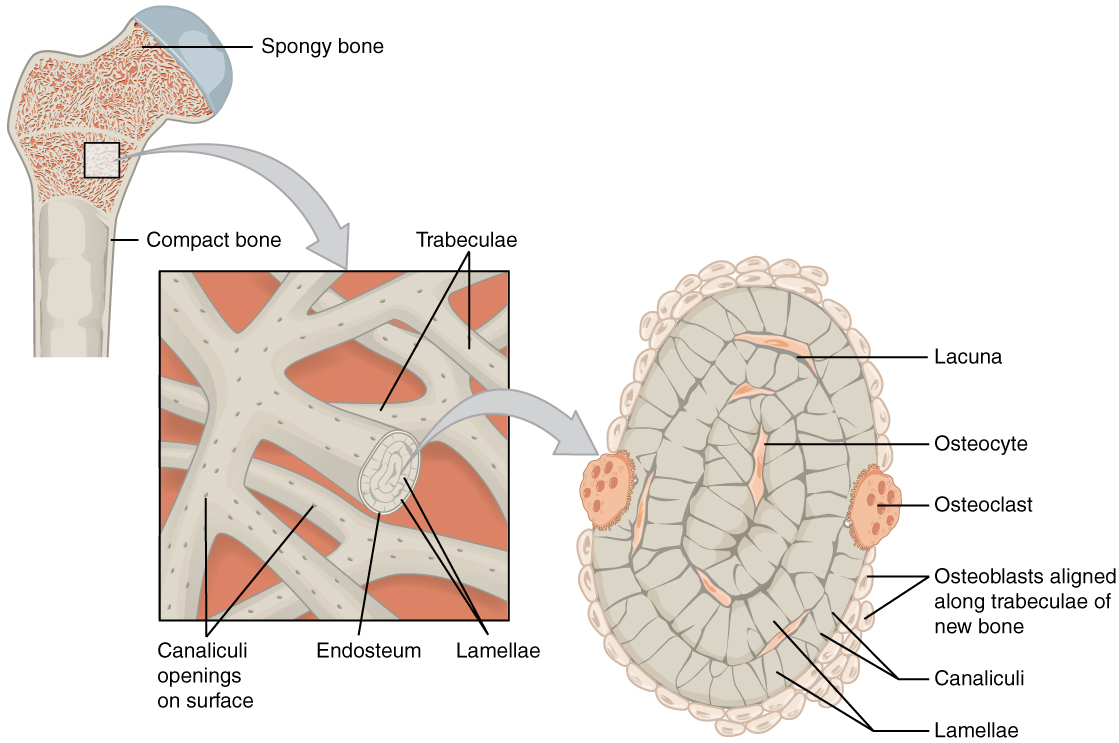

The osteoblast is the bone cell responsible for forming new bone and is found in the growing portions of bone, including the endosteum and the cellular layer of the periosteum. Osteoblasts, which do not divide, synthesize and secrete the collagen matrix and other proteins. As the secreted matrix surrounding the osteoblast calcifies, the osteoblast become trapped within it; as a result, it changes in structure and becomes an osteocyte, the primary cell of mature bone and the most common type of bone cell. Each osteocyte is located in a small cavity in the bone tissue called a lacuna (lacunae for plural). Osteocytes maintain the mineral concentration of the matrix via the secretion of enzymes. Like osteoblasts, osteocytes lack mitotic activity. They can communicate with each other and receive nutrients via long cytoplasmic processes that extend through canaliculi (singular = canaliculus), channels within the bone matrix. Osteocytes are connected to one another within the canaliculi via gap junctions.

If osteoblasts and osteocytes are incapable of mitosis, then how are they replenished when old ones die? The answer lies in the properties of a third category of bone cells—the osteogenic (osteoprogenitor) cell. These osteogenic cells are undifferentiated with high mitotic activity and they are the only bone cells that divide. Immature osteogenic cells are found in the cellular layer of the periosteum and the endosteum. They differentiate and develop into osteoblasts.

The dynamic nature of bone means that new tissue is constantly formed, and old, injured, or unnecessary bone is dissolved for repair or for calcium release. The cells responsible for bone resorption, or breakdown, are the osteoclasts. These multinucleated cells originate from monocytes and macrophages, two types of white blood cells, not from osteogenic cells. Osteoclasts are continually breaking down old bone while osteoblasts are continually forming new bone. The ongoing balance between osteoblasts and osteoclasts is responsible for the constant but subtle reshaping of bone. Table 6.3 reviews the bone cells, their functions, and locations.

| Cell type | Function | Location |

|---|---|---|

| Osteogenic cells | Develop into osteoblasts | Endosteum, cellular layer of the periosteum |

| Osteoblasts | Bone formation | Endosteum, cellular layer of the periosteum, growing portions of bone |

| Osteocytes | Maintain mineral concentration of matrix | Entrapped in matrix |

| Osteoclasts | Bone resorption | Endosteum, cellular layer of the periosteum, at sites of old, injured, or unneeded bone |

Compact and Spongy Bone

Most bones contain compact and spongy osseous tissue, but their distribution and concentration vary based on the bone’s overall function. Although compact and spongy bone are made of the same matrix materials and cells, they are different in how they are organized. Compact bone is dense so that it can withstand compressive forces, while spongy bone (also called cancellous bone) has open spaces and is supportive, but also lightweight and can be readily remodeled to accommodate changing body needs.

Compact Bone

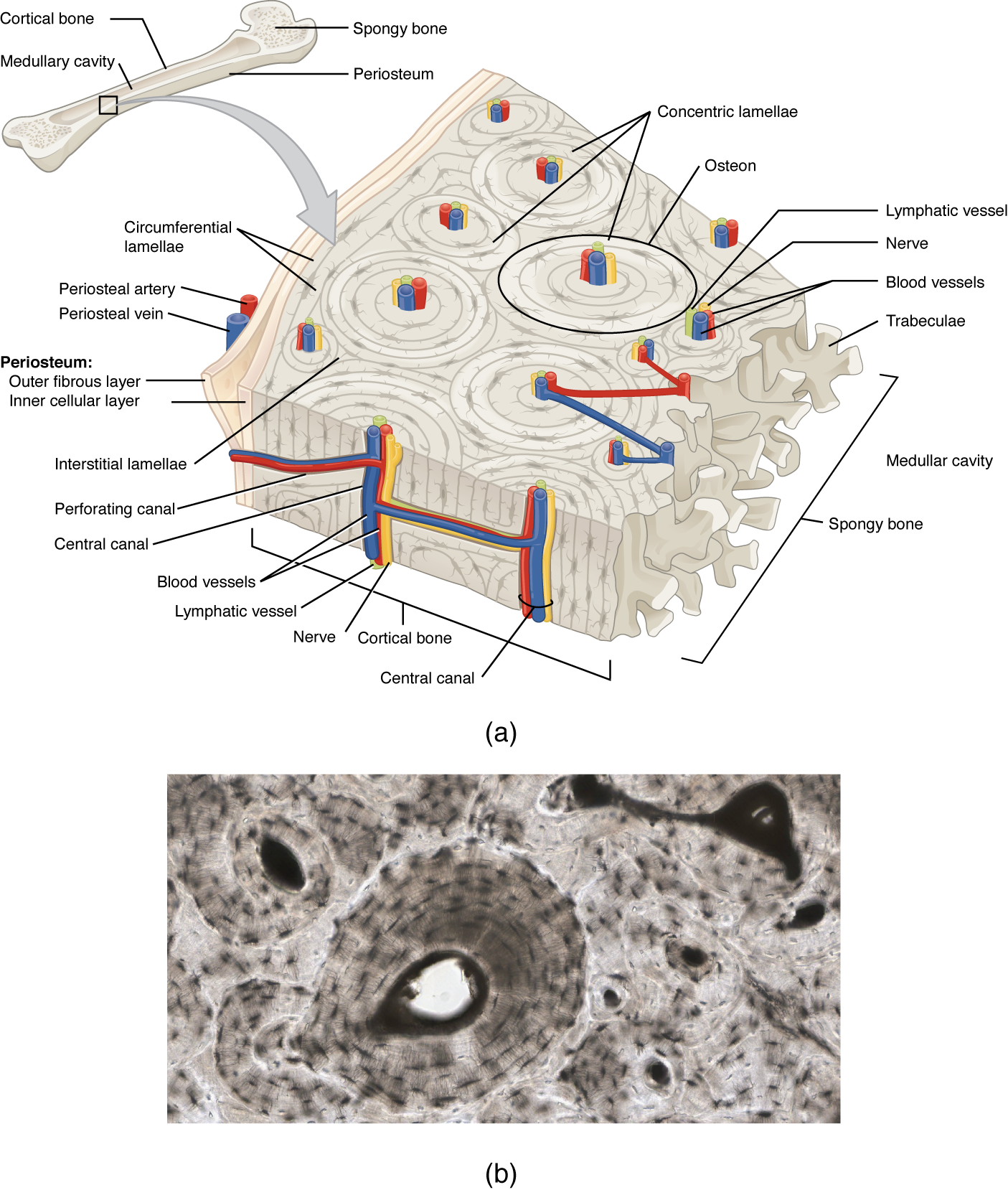

Compact bone is the denser, stronger of the two types of osseous tissue (Figure 6.3.7). It makes up the outer cortex of all bones and is in immediate contact with the periosteum. In long bones, as you move from the outer cortical compact bone to the inner medullary cavity, the bone transitions to spongy bone.

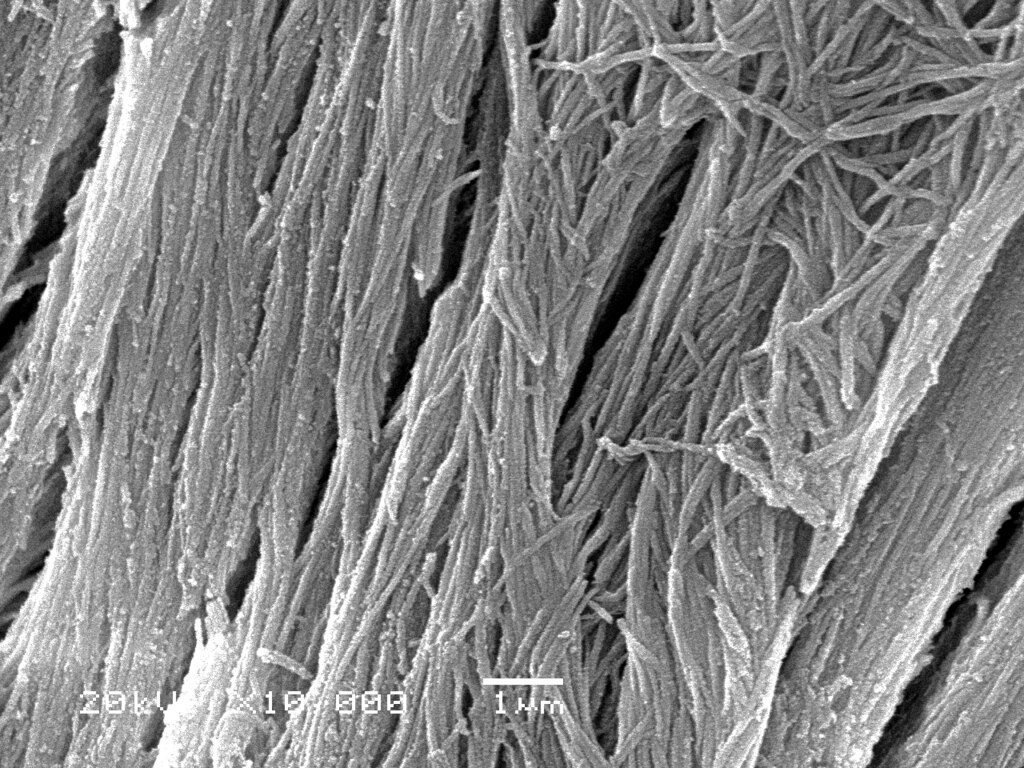

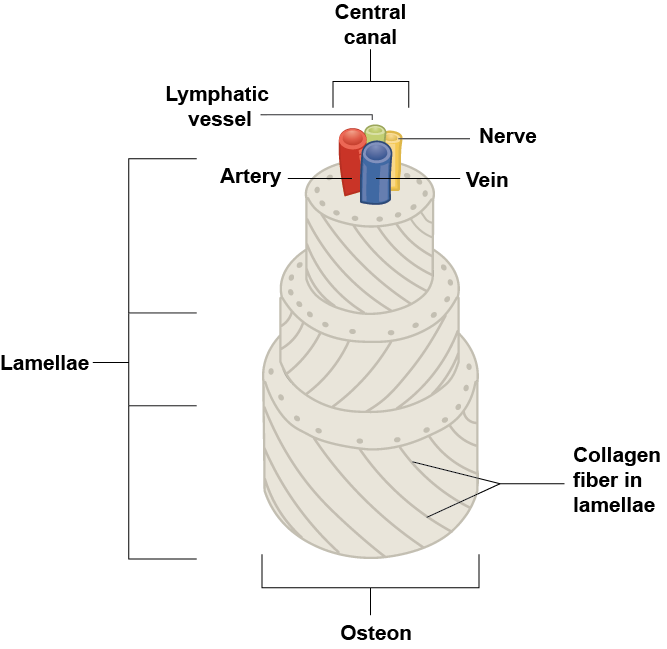

If you look at compact bone under the microscope, you will observe a highly organized arrangement of concentric circles that look like tree trunks. Each group of concentric circles (each “tree”) makes up the microscopic structural unit of compact bone called an osteon (this is also called a Haversian system). Each ring of the osteon is made of collagen and calcified matrix and is called a lamella (plural = lamellae). The collagen fibers of adjacent lamallae run at perpendicular angles to each other, allowing osteons to resist twisting forces in multiple directions (see figure 6.3.5). Running down the center of each osteon is the central canal, or Haversian canal, which contains blood vessels, nerves, and lymphatic vessels. These vessels and nerves branch off at right angles through a perforating canal, also known as Volkmann’s canals, to extend to the periosteum and endosteum. The endosteum also lines each central canal, allowing osteons to be removed, remodeled and rebuilt over time.

The osteocytes are trapped within their lacuane, found at the borders of adjacent lamellae. As described earlier, canaliculi connect with the canaliculi of other lacunae and eventually with the central canal. This system allows nutrients to be transported to the osteocytes and wastes to be removed from them despite the impervious calcified matrix.

Spongy (Cancellous) Bone

Like compact bone, spongy bone, also known as cancellous bone, contains osteocytes housed in lacunae, but they are not arranged in concentric circles. Instead, the lacunae and osteocytes are found in a lattice-like network of matrix spikes called trabeculae (singular = trabecula) (Figure 6.3.9). The trabeculae are covered by the endosteum, which can readily remodel them. The trabeculae may appear to be a random network, but each trabecula forms along lines of stress to direct forces out to the more solid compact bone providing strength to the bone. Spongy bone provides balance to the dense and heavy compact bone by making bones lighter so that muscles can move them more easily. In addition, the spaces in some spongy bones contain red bone marrow, protected by the trabeculae, where hematopoiesis occurs.

Aging and the Skeletal System: Paget’s Disease

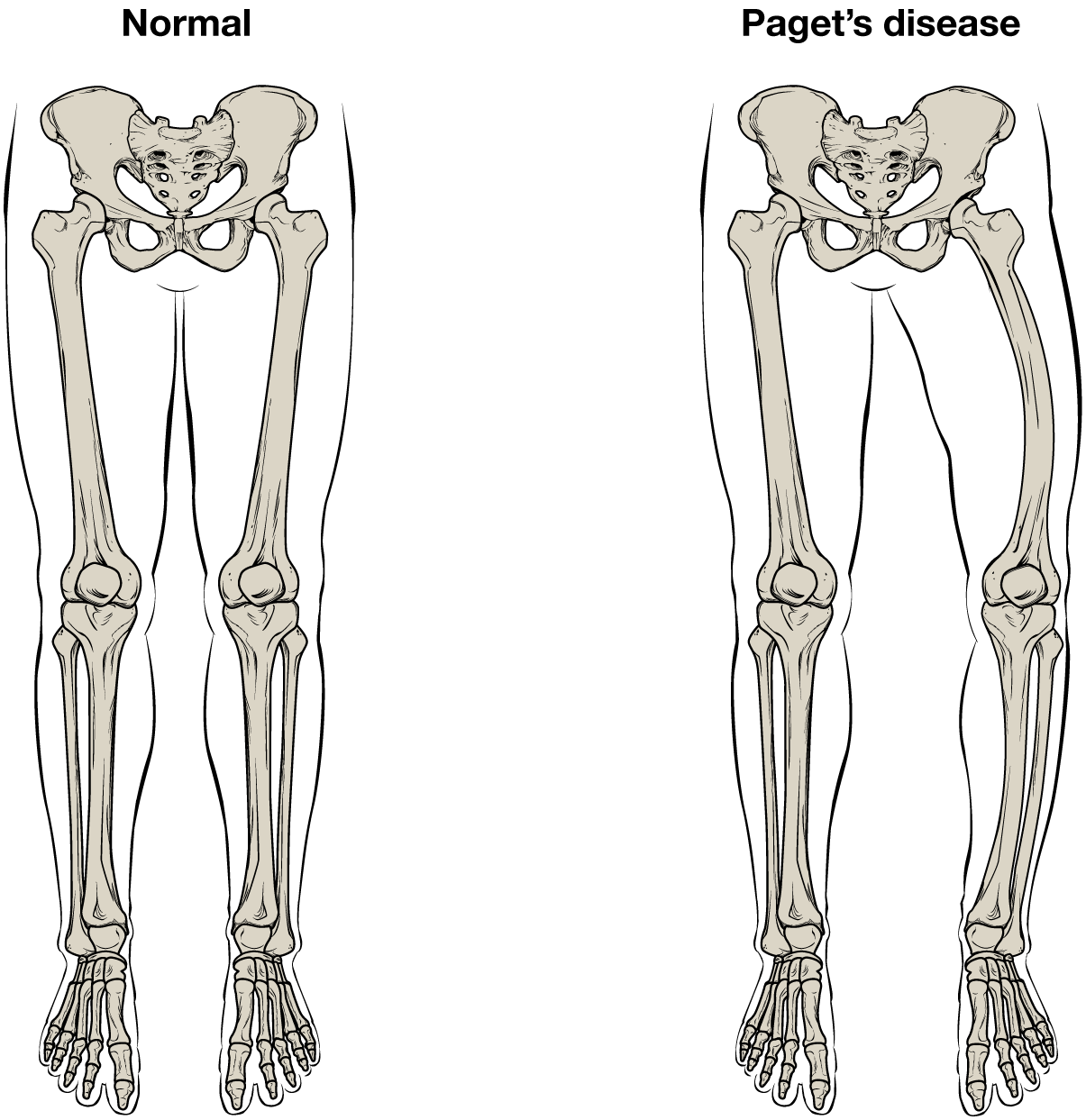

Paget’s disease usually occurs in adults over age 40. It is a disorder of the bone remodeling process that begins with overactive osteoclasts. This means more bone is resorbed than is laid down. The osteoblasts try to compensate but the new bone they lay down is weak and brittle and therefore prone to fracture.

While some people with Paget’s disease have no symptoms, others experience pain, bone fractures, and bone deformities (Figure 6.3.10). Bones of the pelvis, skull, spine, and legs are the most commonly affected. When occurring in the skull, Paget’s disease can cause headaches and hearing loss.

What causes the osteoclasts to become overactive? The answer is still unknown, but hereditary factors seem to play a role. Some scientists believe Paget’s disease is due to an as-yet-unidentified virus.

Paget’s disease is diagnosed via imaging studies and lab tests. X-rays may show bone deformities or areas of bone resorption. Bone scans are also useful. In these studies, a dye containing a radioactive ion is injected into the body. Areas of bone resorption have an affinity for the ion, so they will light up on the scan if the ions are absorbed. In addition, blood levels of an enzyme called alkaline phosphatase are typically elevated in people with Paget’s disease. Bisphosphonates, drugs that decrease the activity of osteoclasts, are often used in the treatment of Paget’s disease.

Blood and Nerve Supply

The spongy bone and medullary cavity receive nourishment from arteries that pass through the compact bone. The arteries enter through the nutrient foramen (plural = foramina), small openings in the diaphysis (Figure 6.3.11). The osteocytes in spongy bone are nourished by blood vessels of the periosteum that penetrate spongy bone and blood that circulates in the marrow cavities. As the blood passes through the marrow cavities, it is collected by veins, which then pass out of the bone through the foramina.

In addition to the blood vessels, nerves follow the same paths into the bone where they tend to concentrate in the more metabolically active regions of the bone. The nerves sense pain, and it appears the nerves also play roles in regulating blood supplies and in bone growth, hence their concentrations in metabolically active sites of the bone.

Resource Link

Watch this video to see the microscopic features of a bone.

Chapter Review

A hollow medullary cavity filled with yellow marrow runs the length of the diaphysis of a long bone. The walls of the diaphysis are compact bone. The epiphyses, which are wider sections at each end of a long bone, are filled with spongy bone and red marrow. The epiphyseal plate, a layer of hyaline cartilage, is replaced by osseous tissue as the organ grows in length. The medullary cavity has a delicate membranous lining called the endosteum. The outer surface of bone, except in regions covered with articular cartilage, is covered with a fibrous membrane called the periosteum. Flat bones consist of two layers of compact bone surrounding a layer of spongy bone. Bone markings depend on the function and location of bones. Articulations are places where two bones meet. Projections stick out from the surface of the bone and provide attachment points for tendons and ligaments. Holes are openings or depressions in the bones.

Bone matrix consists of collagen fibers and organic ground substance, primarily hydroxyapatite formed from calcium salts. Osteogenic cells develop into osteoblasts. Osteoblasts are cells that make new bone. They become osteocytes, the cells of mature bone, when they get trapped in the matrix. Osteoclasts engage in bone resorption. Compact bone is dense and composed of osteons, while spongy bone is less dense and made up of trabeculae. Blood vessels and nerves enter the bone through the nutrient foramina to nourish and innervate bones.

Review Questions

Critical Thinking Questions

If the articular cartilage at the end of one of your long bones were to degenerate, what symptoms do you think you would experience? Why?

Reveal

In what ways is the structural makeup of compact and spongy bone well suited to their respective functions?

Reveal

Glossary

- articular cartilage

- thin layer of hyaline cartilage that covers articulating surfaces of bones at a synovial joint; reduces friction and acts as a shock absorber

- articulation

- joint of the body (where two bone surfaces meet)

- canaliculi

- (singular = canaliculus) channels within the bone matrix that house one of an osteocyte’s many cytoplasmic extensions that it uses to communicate and receive nutrients

- central canal of the osteon

- longitudinal channel in the center of each osteon; contains blood vessels, nerves, and lymphatic vessels; also known as the Haversian canal

- compact bone

- dense osseous tissue that can withstand compressive forces

- diaphysis

- tubular shaft that runs between the proximal and distal ends of a long bone

- diploë

- layer of spongy bone, that is sandwiched between two the layers of compact bone found in flat bones

- endosteum

- delicate membranous lining of a bone’s medullary cavity

- epiphyseal line

- completely ossified remnant of the epiphyseal plate

- epiphyseal plate

- (also, growth plate) junction between epiphysis and diaphysis in the metaphysis of a growing long bone where a sheet of hyaline cartilage is replaced by bone tissue as the organ grows in length

- epiphysis

- wide section at each end of a long bone; filled with spongy bone and red marrow

- hole

- opening or depression in a bone

- lacunae (of the bones)

- (singular = lacuna) spaces in a bone that house an osteocyte

- medullary cavity

- hollow region of the diaphysis; filled with yellow marrow

- nutrient foramen

- small opening in the middle of the external surface of the diaphysis, through which an artery enters the bone to provide nourishment

- osteoblast

- cell responsible for forming new bone

- osteoclast

- cell responsible for resorbing bone

- osteocyte

- primary cell in mature bone; responsible for maintaining the matrix

- osteogenic cell

- undifferentiated cell with high mitotic activity; the only bone cells that divide; they differentiate and develop into osteoblasts

- osteon

- (also, Haversian system) basic structural unit of compact bone; made of concentric layers of calcified matrix

- perforating canal

- (also, Volkmann’s canal) channel that branches off from the central canal and houses vessels and nerves that extend to the periosteum and endosteum

- periosteum

- fibrous membrane covering the outer surface of bone and continuous with ligaments

- projection

- bone markings where part of the surface sticks out above the rest of the surface, where tendons and ligaments attach

- spongy bone

- (also, cancellous bone) trabeculated osseous tissue that supports shifts in weight distribution

- trabeculae

- (singular = trabecula) spikes or sections of the lattice-like matrix in spongy bone

tubular shaft that runs between the proximal and distal ends of a long bone

hollow region of the diaphysis; filled with yellow marrow

wide section at each end of a long bone; filled with spongy bone and red marrow

(also, growth plate) junction between epiphysis and diaphysis in the metaphysis of a growing long bone where a sheet of hyaline cartilage is replaced by bone tissue as the organ grows in length

completely ossified remnant of the epiphyseal plate

delicate membranous lining of a bone’s medullary cavity

fibrous membrane covering the outer surface of bone and continuous with ligaments

thin layer of hyaline cartilage that covers articulating surfaces of bones at a synovial joint; reduces friction and acts as a shock absorber

layer of spongy bone, that is sandwiched between two the layers of compact bone found in flat bones

joint of the body (where two bone surfaces meet)

bone markings where part of the surface sticks out above the rest of the surface, where tendons and ligaments attach

opening or depression in a bone

cell responsible for forming new bone

primary cell in mature bone; responsible for maintaining the matrix

(singular = lacuna) spaces in a bone that house an osteocyte

(singular = canaliculus) channels within the bone matrix that house one of an osteocyte’s many cytoplasmic extensions that it uses to communicate and receive nutrients

undifferentiated cell with high mitotic activity; the only bone cells that divide; they differentiate and develop into osteoblasts

cell responsible for resorbing bone

dense osseous tissue that can withstand compressive forces

(also, Haversian system) basic structural unit of compact bone; made of concentric layers of calcified matrix

longitudinal channel in the center of each osteon; contains blood vessels, nerves, and lymphatic vessels; also known as the Haversian canal

(also, Volkmann’s canal) channel that branches off from the central canal and houses vessels and nerves that extend to the periosteum and endosteum

(also, cancellous bone) trabeculated osseous tissue that supports shifts in weight distribution

(singular = trabecula) spikes or sections of the lattice-like matrix in spongy bone

small opening in the middle of the external surface of the diaphysis, through which an artery enters the bone to provide nourishment