7.6 Embryonic Development of the Axial Skeleton

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

Discuss the embryonic development of the axial skeleton

- Discuss the two types of embryonic bone development within the skull

- Describe the development of the vertebral column and thoracic cage

The axial skeleton begins to form during early embryonic development. However, growth, remodeling, and ossification (bone formation) continue for several decades after birth before the adult skeleton is fully formed. Knowledge of the developmental processes that give rise to the skeleton is important for understanding the abnormalities that may arise in skeletal structures.

Development of the Skull

During the third week of embryonic development, a rod-like structure called the notochord develops dorsally along the length of the embryo. The tissue overlying the notochord enlarges and forms the neural tube, which will give rise to the brain and spinal cord. By the fourth week, mesoderm tissue located on either side of the notochord thickens and separates into a repeating series of block-like tissue structures, each of which is called a somite. As the somites enlarge, each one will split into several parts. The most medial of these parts is called a sclerotome. The sclerotomes consist of an embryonic tissue called mesenchyme, which will give rise to the fibrous connective tissues, cartilages, and bones of the body.

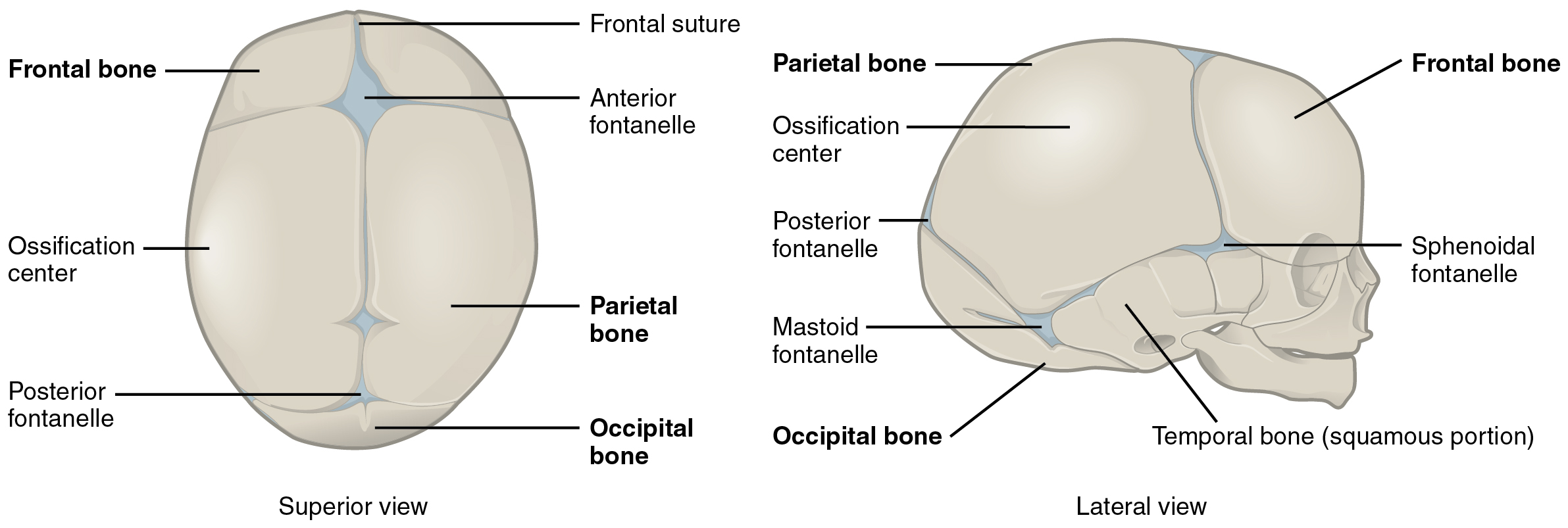

The bones of the skull arise from mesenchyme during embryonic development in two different ways. The first mechanism produces the bones that form the top and sides of the brain case. This involves the local accumulation of mesenchymal cells at the site of the future bone. These cells then differentiate directly into bone producing cells, which form the skull bones through the process of intramembranous ossification. As the cranial bones grow in the fetal skull, they remain separated from each other by large areas of dense connective tissue, each of which is called a fontanelle (Figure 7.6.1). The fontanelles are the soft spots on an infant’s head. They are important during birth because these areas allow the skull to change shape as it squeezes through the birth canal. As part of the newborn exam, fontanelles are palpated for bulging which indicates increased intracranial pressure often associated with hydrocephalus. After birth, the fontanelles allow for continued growth and expansion of the skull as the brain enlarges. The largest fontanelle is located on the anterior head, at the junction of the frontal and parietal bones. The fontanelles decrease in size and disappear by age 2. However, the skull bones remained separated from each other at the sutures, which contain dense fibrous connective tissue that unites the adjacent bones. The connective tissue of the sutures allows for continued growth of the skull bones as the brain enlarges during childhood growth.

The second mechanism for bone development in the skull produces the facial bones and floor of the brain case. This also begins with the localized accumulation of mesenchymal cells. However, these cells differentiate into cartilage cells, which produce a hyaline cartilage model of the future bone. As this cartilage model grows, it is gradually converted into bone through the process of endochondral ossification. This is a slow process and the cartilage is not completely converted to bone until the skull achieves its full adult size.

At birth, the brain case and orbits of the skull are disproportionally large compared to the bones of the jaws and lower face. This reflects the relative underdevelopment of the maxilla and mandible, which lack teeth, and the small sizes of the paranasal sinuses and nasal cavity. During early childhood, the mastoid process enlarges, the two halves of the mandible and frontal bone fuse together to form single bones, and the paranasal sinuses enlarge. The jaws also expand as the teeth begin to appear. These changes all contribute to the rapid growth and enlargement of the face during childhood.

Development of the Vertebral Column and Thoracic cage

Development of the vertebrae begins with the accumulation of mesenchyme cells from each sclerotome around the notochord. These cells differentiate into a hyaline cartilage model for each vertebra, which then grow and eventually ossify into bone through the process of endochondral ossification. As the developing vertebrae grow, the notochord largely disappears. However, small areas of notochord tissue persist between the adjacent vertebrae as the nucleus pulposus and this contributes to the formation of each intervertebral disc.

The ribs and sternum also develop from mesenchyme. The ribs initially develop as part of the cartilage model for each vertebra, but in the thorax region, the rib portion separates from the vertebra by the eighth week. The cartilage model of the rib then ossifies, except for the anterior portion, which remains as the costal cartilage. The sternum initially forms as paired hyaline cartilage models on either side of the anterior midline, beginning during the fifth week of development. The cartilage models of the ribs become attached to the lateral sides of the developing sternum. Eventually, the two halves of the cartilaginous sternum fuse together along the midline and then ossify into bone. The manubrium and body of the sternum are converted into bone first, with the xiphoid process remaining as cartilage until late in life.

External Website

View this video to review the two processes that give rise to the bones of the skull and body. What are the two mechanisms by which the bones of the body are formed and which bones are formed by each mechanism?

External Website

View this video to review the two processes that give rise to the bones of the skull and body. What are the two mechanisms by which the bones of the body are formed and which bones are formed by each mechanism?

The premature closure (fusion) of a suture line is a condition called craniosynostosis. This error in the normal developmental process results in abnormal growth of the skull and deformity of the head. It is produced either by defects in the ossification process of the skull bones or failure of the brain to properly enlarge. Genetic factors are involved, but the underlying cause is unknown. It is a relatively common condition, occurring in approximately 1:2000 births, with males being more commonly affected. Primary craniosynostosis involves the early fusion of one cranial suture, whereas complex craniosynostosis results from the premature fusion of several sutures.

The early fusion of a suture in primary craniosynostosis prevents any additional enlargement of the cranial bones and skull along this line. Continued growth of the brain and skull is therefore diverted to other areas of the head, causing an abnormal enlargement of these regions. For example, the early disappearance of the anterior fontanelle and premature closure of the sagittal suture prevents growth across the top of the head. This is compensated by upward growth by the bones of the lateral skull, resulting in a long, narrow, wedge-shaped head. This condition, known as scaphocephaly, accounts for approximately 50 percent of craniosynostosis abnormalities. Although the skull is misshapen, the brain still has adequate room to grow and thus there is no accompanying abnormal neurological development.

In cases of complex craniosynostosis, several sutures close prematurely. The amount and degree of skull deformity is determined by the location and extent of the sutures involved. This results in more severe constraints on skull growth, which can alter or impede proper brain growth and development.

Cases of craniosynostosis are usually treated with surgery. A team of physicians will open the skull along the fused suture, which will then allow the skull bones to resume their growth in this area. In some cases, parts of the skull will be removed and replaced with an artificial plate. The earlier after birth that surgery is performed, the better the outcome. After treatment, most children continue to grow and develop normally and do not exhibit any neurological problems.

Chapter Review

Formation of the axial skeleton begins during early embryonic development with the appearance of the rod-like notochord along the dorsal length of the early embryo. Repeating, paired blocks of tissue called somites then appear along either side of notochord. As the somites grow, they split into parts, one of which is called a sclerotome. This consists of mesenchyme, the embryonic tissue that will become the bones, cartilages, and connective tissues of the body.

Mesenchyme in the head region will produce the bones of the skull via two different mechanisms. The bones of the brain case arise via intramembranous ossification in which embryonic mesenchyme tissue converts directly into bone. At the time of birth, these bones are separated by fontanelles, wide areas of fibrous connective tissue. As the bones grow, the fontanelles are reduced to sutures, which allow for continued growth of the skull throughout childhood. In contrast, the cranial base and facial bones are produced by the process of endochondral ossification, in which mesenchyme tissue initially produces a hyaline cartilage model of the future bone. The cartilage model allows for growth of the bone and is gradually converted into bone over a period of many years.

The vertebrae, ribs, and sternum also develop via endochondral ossification. Mesenchyme accumulates around the notochord and produces hyaline cartilage models of the vertebrae. The notochord largely disappears, but remnants of the notochord contribute to formation of the intervertebral discs. In the thorax region, a portion of the vertebral cartilage model splits off to form the ribs. These then become attached anteriorly to the developing cartilage model of the sternum. Growth of the cartilage models for the vertebrae, ribs, and sternum allow for enlargement of the thoracic cage during childhood and adolescence. The cartilage models gradually undergo ossification and are converted into bone.

Interactive Link Questions

View this video to review the two processes that give rise to the bones of the skull and body. What are the two mechanisms by which the bones of the body are formed and which bones are formed by each mechanism?

Bones on the top and sides of the skull develop when fibrous membrane areas ossify (convert) into bone. The bones of the limbs, ribs, and vertebrae develop when cartilage models of the bones ossify into bone.

Review Questions

Critical Thinking Questions

1. Discuss the processes by which the brain-case bones of the skull are formed and grow during skull enlargement.

2. Discuss the process that gives rise to the base and facial bones of the skull.

3. Discuss the development of the vertebrae, ribs, and sternum.

Glossary

- fontanelle

- expanded area of fibrous connective tissue that separates the brain case bones of the skull prior to birth and during the first year after birth

- notochord

- rod-like structure along dorsal side of the early embryo; largely disappears during later development but does contribute to formation of the intervertebral discs

- sclerotome

- medial portion of a somite consisting of mesenchyme tissue that will give rise to bone, cartilage, and fibrous connective tissues

- somite

- one of the paired, repeating blocks of tissue located on either side of the notochord in the early embryo

Solutions

Answers for Critical Thinking Questions

- The brain-case bones that form the top and sides of the skull are produced by intramembranous ossification. In this, mesenchyme from the sclerotome portion of the somites accumulates at the site of the future bone and differentiates into bone-producing cells. These generate areas of bone that are initially separated by wide regions of fibrous connective tissue called fontanelles. After birth, as the bones enlarge, the fontanelles disappear. However, the bones remain separated by the sutures, where bone and skull growth can continue until the adult size is obtained.

- The facial bones and base of the skull arise via the process of endochondral ossification. This process begins with the localized accumulation of mesenchyme tissue at the sites of the future bones. The mesenchyme differentiates into hyaline cartilage, which forms a cartilage model of the future bone. The cartilage allows for growth and enlargement of the model. It is gradually converted into bone over time.

- The vertebrae, ribs, and sternum all develop via the process of endochondral ossification. Mesenchyme tissue from the sclerotome portion of the somites accumulates on either side of the notochord and produces hyaline cartilage models for each vertebra. In the thorax region, a portion of this cartilage model splits off to form the ribs. Similarly, mesenchyme forms cartilage models for the right and left halves of the sternum. The ribs then become attached anteriorly to the developing sternum, and the two halves of sternum fuse together. Ossification of the cartilage model into bone occurs within these structures over time. This process continues until each is converted into bone, except for the sternal ends of the ribs, which remain as the costal cartilages.

This work, Anatomy & Physiology, is adapted from Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax, licensed under CC BY. This edition, with revised content and artwork, is licensed under CC BY-SA except where otherwise noted.

Images, from Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax, are licensed under CC BY except where otherwise noted.

Access the original for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction.