5.2 The Viral Life Cycle

Learning Objectives

- Describe the steps of the replication process of animal viruses

- Describe unique characteristics of retroviruses and latent viruses

- Compare the different types of persistent infections

- Understand the components of a viral growth curve

All viruses depend on cells for reproduction and metabolic processes. By themselves, viruses do not encode for all of the enzymes necessary for viral replication. But within a host cell, a virus can commandeer cellular machinery to produce more viral particles.

Life Cycle of Viruses with Animal Hosts

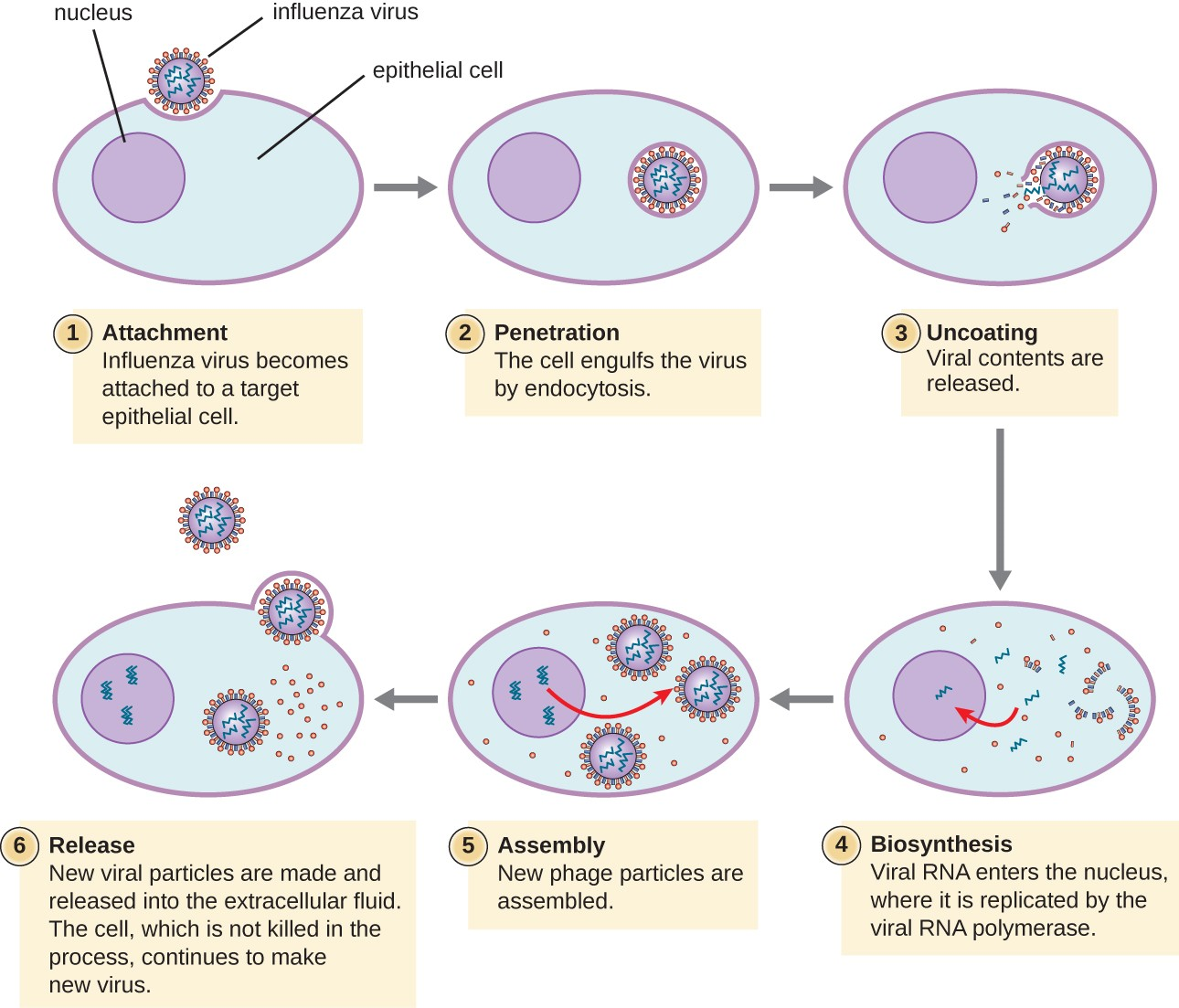

Lytic animal viruses go through the following stages to replicate: attachment, penetration, uncoating, biosynthesis, maturation, and release (see Figure 5.7). After binding to host receptors, animal viruses enter through endocytosis (engulfment by the host cell) or through membrane fusion (viral envelope with the host cell membrane).

Many viruses are host specific, meaning they only infect a certain type of host; and most viruses only infect certain types of cells within tissues. This specificity is called a tissue tropism.

Animal viruses do not always express their genes using the normal flow of genetic information—from DNA to RNA to protein. Some viruses have a dsDNA genome like cellular organisms and can follow the normal flow. However, others may have ssDNA, dsRNA, or ssRNA genomes. The nature of the genome determines how the genome is replicated and expressed as viral proteins. If a genome is ssDNA, host enzymes will be used to synthesize a second strand that is complementary to the genome strand, thus producing dsDNA. The dsDNA can now be replicated, transcribed, and translated similar to host DNA.

If the viral genome is RNA, a different mechanism must be used. Single-stranded RNA viruses such as HIV carry a special enzyme called reverse transcriptase within the capsid that synthesizes a complementary ssDNA (cDNA) copy using the +ssRNA genome as a template. The ssDNA is then made into dsDNA, which can integrate into the host chromosome and become a permanent part of the host. The integrated viral genome is called a provirus. The virus now can remain in the host for a long time to establish a chronic infection.

![]()

- Why does HIV have to use the enzyme reverse transcriptase?

Persistent Infections

Latent Infection

Not all animal viruses undergo replication by the lytic cycle. There are viruses that are capable of remaining hidden or dormant inside the cell in a process called latency. These types of viruses are known as latent viruses and may cause latent infections. Viruses capable of latency may initially cause an acute infection before becoming dormant.

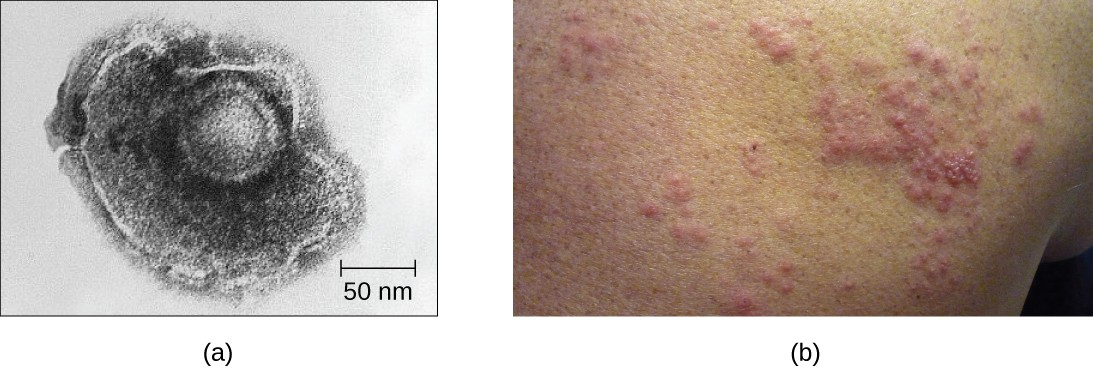

For example, the varicella-zoster virus infects many cells throughout the body and causes chickenpox, characterized by a rash of blisters covering the skin. About 10 to 12 days postinfection, the disease resolves and the virus goes dormant, living within nerve-cell ganglia for years. During this time, the virus does not kill the nerve cells or continue replicating. It is not clear why the virus stops replicating within the nerve cells and expresses few viral proteins but, in some cases, typically after many years of dormancy, the virus is reactivated and causes a new disease called shingles (Figure 5.8). Whereas chickenpox affects many areas throughout the body, shingles is a nerve cell-specific disease emerging from the ganglia in which the virus was dormant.

Latent viruses may remain dormant by existing as circular viral genome molecules outside of the host chromosome. Others become proviruses by integrating into the host genome. During dormancy, viruses do not cause any symptoms of disease and may be difficult to detect. A patient may be unaware that he or she is carrying the virus unless a viral diagnostic test has been performed.

Chronic Infection

A chronic infection is a disease with symptoms that are recurrent or persistent over a long time. Some viral infections can be chronic if the body is unable to eliminate the virus. HIV is an example of a virus that produces a chronic infection, often after a long period of latency. Once a person becomes infected with HIV, the virus can be detected in tissues continuously thereafter, but untreated patients often experience no symptoms for years. However, the virus maintains chronic persistence through several mechanisms that interfere with immune function, including preventing expression of viral antigens on the surface of infected cells, altering immune cells themselves, restricting expression of viral genes, and rapidly changing viral antigens through mutation. Eventually, the damage to the immune system results in progression of the disease leading to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). The various mechanisms that HIV uses to avoid being cleared by the immune system are also used by other chronically infecting viruses, including the hepatitis C virus.

![]()

- In what two ways can a virus manage to maintain a persistent infection?

Viral Growth Curve

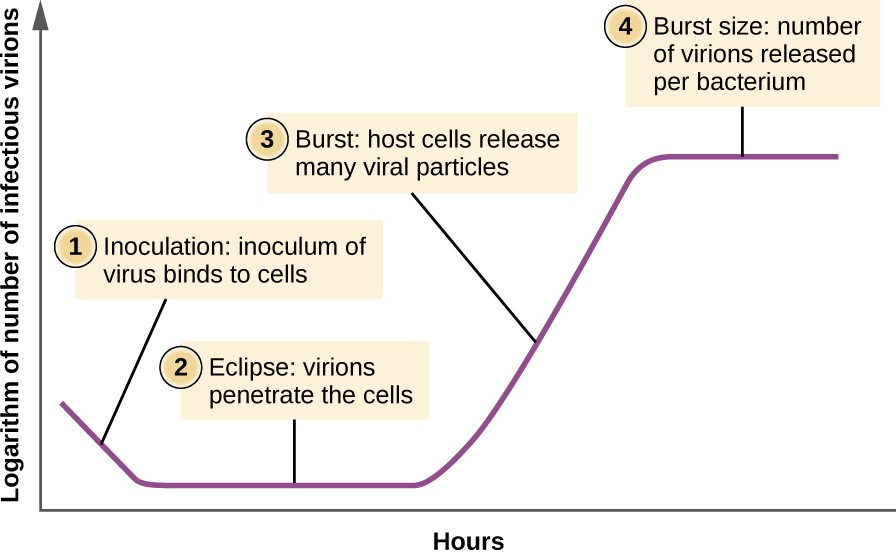

Unlike the growth curve for a bacterial population, the growth curve for a virus population over its life cycle does not follow a sigmoidal curve. During the initial stage, an inoculum of virus causes infection. In the eclipse phase, viruses bind and penetrate the cells with no virions detected in the medium. The chief difference that next appears in the viral growth curve compared to a bacterial growth curve occurs when virions are released from the lysed host cell at the same time. Such an occurrence is called a burst, and the number of virions per bacterium released is described as the burst size. In a one-step multiplication curve for bacteriophage, the host cells lyse, releasing many viral particles to the medium, which leads to a very steep rise in viral titer (the number of virions per unit volume). If no viable host cells remain, the viral particles begin to degrade during the decline of the culture (see Figure 5.9).

![]()

- What aspect of the life cycle of a virus leads to the sudden increase in the growth curve?

Case in Point

Ebola in the US

On September 24, 2014, Thomas Eric Duncan arrived at the Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital in Dallas complaining of a fever, headache, vomiting, and diarrhea—symptoms commonly observed in patients with the cold or the flu. After examination, an emergency department doctor diagnosed him with sinusitis, prescribed some antibiotics, and sent him home. Two days later, Duncan returned to the hospital by ambulance. His condition had deteriorated and additional blood tests confirmed that he has been infected with the Ebola virus.

Further investigations revealed that Duncan had just returned from Liberia, one of the countries in the midst of a severe Ebola epidemic. On September 15, nine days before he showed up at the hospital in Dallas, Duncan had helped transport an Ebola-stricken neighbor to a hospital in Liberia. The hospital continued to treat Duncan, but he died several days after being admitted.

The timeline of the Duncan case is indicative of the life cycle of the Ebola virus. The incubation time for Ebola ranges from 2 days to 21 days. Nine days passed between Duncan’s exposure to the virus infection and the appearance of his symptoms. This corresponds, in part, to the eclipse period in the growth of the virus population. During the eclipse phase, Duncan would have been unable to transmit the disease to others. However, once an infected individual begins exhibiting symptoms, the disease becomes very contagious. Ebola virus is transmitted through direct contact with droplets of bodily fluids such as saliva, blood, and vomit. Duncan could conceivably have transmitted the disease to others at any time after he began having symptoms, presumably some time before his arrival at the hospital in Dallas. Once a hospital realizes a patient like Duncan is infected with Ebola virus, the patient is immediately quarantined, and public health officials initiate a back trace to identify everyone with whom a patient like Duncan might have interacted during the period in which he was showing symptoms.

Public health officials were able to track down 10 high-risk individuals (family members of Duncan) and 50 low-risk individuals to monitor them for signs of infection. None contracted the disease. However, one of the nurses charged with Duncan’s care did become infected. This, along with Duncan’s initial misdiagnosis, made it clear that US hospitals needed to provide additional training to medical personnel to prevent a possible Ebola outbreak in the US.

- What types of training can prepare health professionals to contain emerging epidemics like the Ebola outbreak of 2014?

- What is the difference between a contagious pathogen and an infectious pathogen?

Link to Learning

For additional information about Ebola, please visit the CDC website (https://www.openstax.org/l/22ebolacdc) .