21.1 Anatomy of the Nervous System

Learning Objectives

- Describe the major anatomical features of the nervous system

- Explain why there is no normal microbiota of the nervous system

- Explain how microorganisms overcome defenses of the nervous system to cause infection

- Identify and describe general symptoms associated with various infections of the nervous system

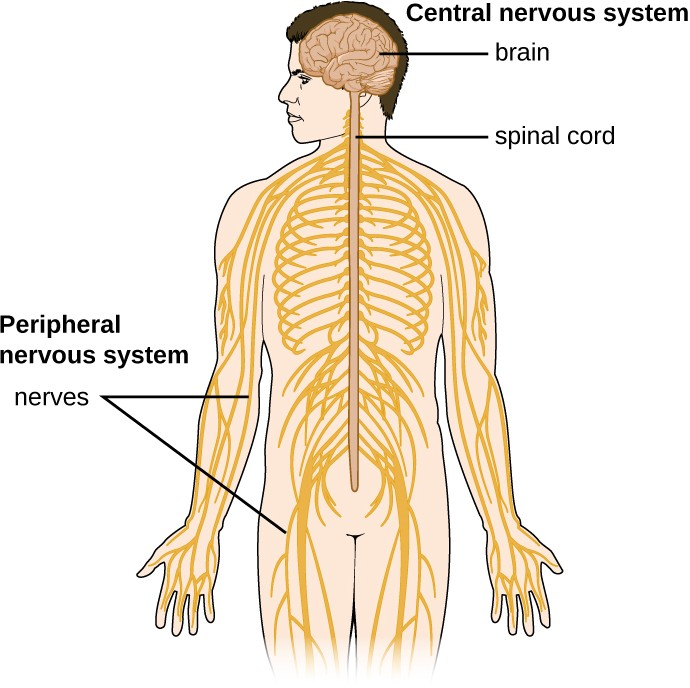

The human nervous system can be divided into two interacting subsystems: the peripheral nervous system (PNS) and the central nervous system (CNS). The CNS consists of the brain and spinal cord. The peripheral nervous system is an extensive network of nerves connecting the CNS to the muscles and sensory structures. The relationship of these systems is illustrated in Figure 21.2

The Central Nervous System

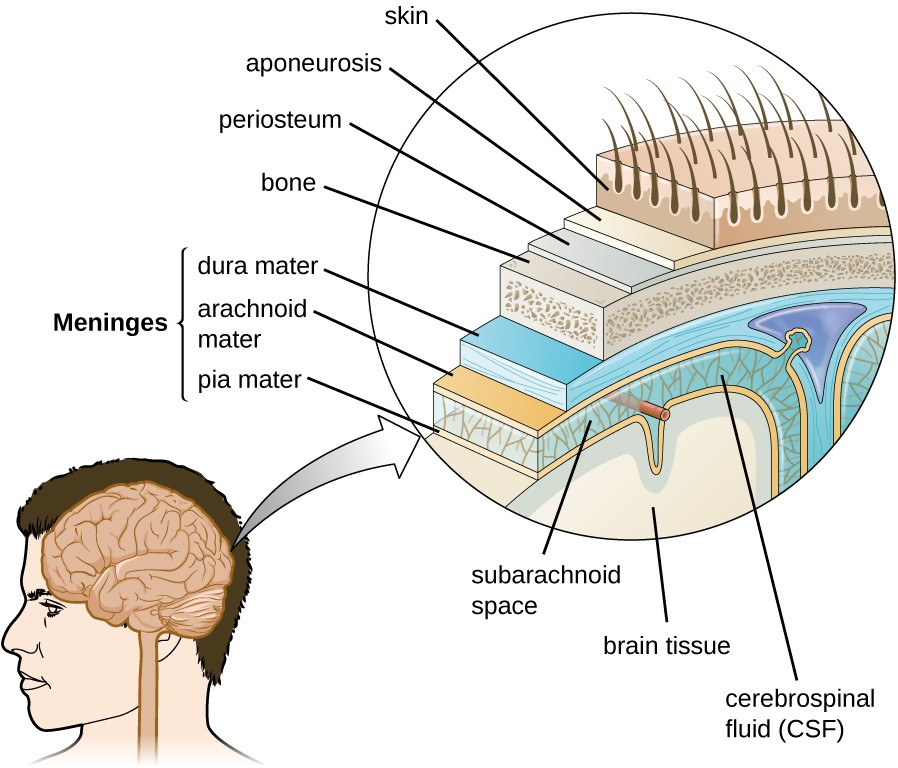

The brain is the most complex and sensitive organ in the body. It is responsible for all functions of the body, including serving as the coordinating center for all sensations, mobility, emotions, and intellect. Protection for the brain is provided by the bones of the skull, which in turn are covered by the scalp, as shown in Figure 21.3. The scalp is composed of an outer layer of skin, which is loosely attached to the aponeurosis, a flat, broad tendon layer that anchors the superficial layers of the skin. The periosteum, below the aponeurosis, firmly encases the bones of the skull and provides protection, nutrition to the bone, and the capacity for bone repair. Below the boney layer of the skull are three layers of membranes called meninges that surround the brain. The relative positions of these meninges are shown in Figure 21.3. The meningeal layer closest to the bones of the skull is called the dura mater (literally meaning tough mother). Below the dura mater lies the arachnoid mater (literally spider-like mother). The innermost meningeal layer is a delicate membrane called the pia mater (literally tender mother). Unlike the other meningeal layers, the pia mater firmly adheres to the convoluted surface of the brain. Between the arachnoid mater and pia mater is the subarachnoid space. The subarachnoid space within this region is filled with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). This watery fluid is produced by cells of the choroid plexus—areas in each ventricle of the brain that consist of cuboidal epithelial cells surrounding dense capillary beds. The CSF serves to deliver nutrients and remove waste from neural tissues.

The Blood-Brain Barrier

The tissues of the CNS have extra protection in that they are not exposed to blood or the immune system in the same way as other tissues. The blood vessels that supply the brain with nutrients and other chemical substances lie on top of the pia mater. The capillaries associated with these blood vessels in the brain are less permeable than those in other locations in the body. The capillary endothelial cells form tight junctions that control the transfer of blood components to the brain. In addition, cranial capillaries have far fewer fenestra (pore-like structures that are sealed by a membrane) and pinocytotic vesicles than other capillaries. As a result, materials in the circulatory system have a very limited ability to interact with the CNS directly. This phenomenon is referred to as the blood-brain barrier.

The blood-brain barrier protects the cerebrospinal fluid from contamination, and can be quite effective at excluding potential microbial pathogens. As a consequence of these defenses, there is no normal microbiota in the cerebrospinal fluid. The blood-brain barrier also inhibits the movement of many drugs into the brain, particularly compounds that are not lipid soluble. This has profound ramifications for treatments involving infections of the CNS, because it is difficult for drugs to cross the blood-brain barrier to interact with pathogens that cause infections.

The spinal cord also has protective structures similar to those surrounding the brain. Within the bones of the vertebrae are meninges of dura mater (sometimes called the dural sheath), arachnoid mater, pia mater, and a blood-spinal cord barrier that controls the transfer of blood components from blood vessels associated with the spinal cord.

To cause an infection in the CNS, pathogens must successfully breach the blood-brain barrier or blood-spinal cord barrier.

![]()

- What is the primary function of the blood-brain barrier?

The Peripheral Nervous System

The PNS is formed of the nerves that connect organs, limbs, and other anatomic structures of the body to the brain and spinal cord. Unlike the brain and spinal cord, the PNS is not protected by bone, meninges, or a blood barrier, and, as a consequence, the nerves of the PNS are much more susceptible to injury and infection. Microbial damage to peripheral nerves can lead to tingling or numbness known as neuropathy. These symptoms can also be produced by trauma and noninfectious causes such as drugs or chronic diseases like diabetes.

The Cells of the Nervous System

Tissues of the PNS and CNS are formed of cells called glial cells (neuroglial cells) and neurons (nerve cells). Glial cells assist in the organization of neurons, provide a scaffold for some aspects of neuronal function, and aid in recovery from neural injury.

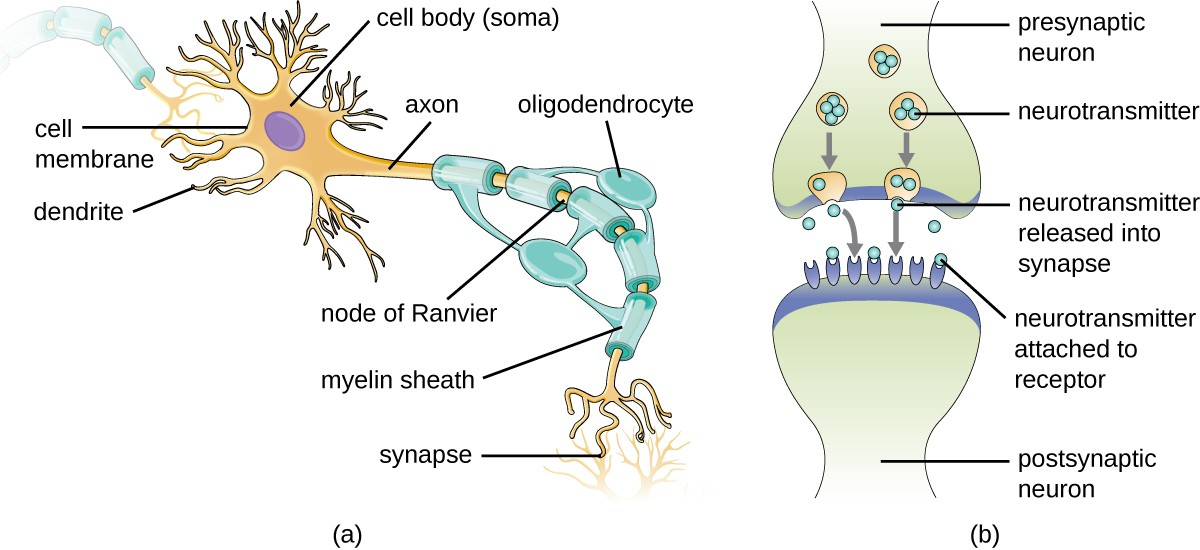

Neurons are specialized cells found throughout the nervous system that transmit signals through the nervous system using electrochemical processes. The basic structure of a neuron is shown in Figure 21.4. The cell body (or soma) is the metabolic center of the neuron and contains the nucleus and most of the cell’s organelles. The many finely branched extensions from the soma are called dendrites. The soma also produces an elongated extension, called the axon, which is responsible for the transmission of electrochemical signals through elaborate ion transport processes. Axons of some types of neurons can extend up to one meter in length in the human body. To facilitate electrochemical signal transmission, some neurons have a myelin sheath surrounding the axon. Myelin, formed from the cell membranes of glial cells like the Schwann cells in the PNS and oligodendrocytes in the CNS, surrounds and insulates the axon, significantly increasing the speed of electrochemical signal transmission along the axon. The end of an axon forms numerous branches that end in bulbs called synaptic terminals. Neurons form junctions with other cells, such as another neuron, with which they exchange signals. The junctions, which are actually gaps between neurons, are referred to as synapses. At each synapse, there is a presynaptic neuron and a postsynaptic neuron (or other cell). The synaptic terminals of the axon of the presynaptic terminal form the synapse with the dendrites, soma, or sometimes the axon of the postsynaptic neuron, or a part of another type of cell such as a muscle cell. The synaptic terminals contain vesicles filled with chemicals called neurotransmitters. When the electrochemical signal moving down the axon reaches the synapse, the vesicles fuse with the membrane, and neurotransmitters are released, which diffuse across the synapse and bind to receptors on the membrane of the postsynaptic cell, potentially initiating a response in that cell. That response in the postsynaptic cell might include further propagation of an electrochemical signal to transmit information or contraction of a muscle fiber.

Meningitis and Encephalitis

Although the skull provides the brain with an excellent defense, it can also become problematic during infections. Any swelling of the brain or meninges that results from inflammation can cause intracranial pressure, leading to severe damage of the brain tissues, which have limited space to expand within the inflexible bones of the skull. The term meningitis is used to describe an inflammation of the meninges. Typical symptoms can include severe headache, fever, photophobia (increased sensitivity to light), stiff neck, convulsions, and confusion. An inflammation of brain tissue is called encephalitis, and patients exhibit signs and symptoms similar to those of meningitis in addition to lethargy, seizures, and personality changes. When inflammation affects both the meninges and the brain tissue, the condition is called meningoencephalitis. All three forms of inflammation are serious and can lead to blindness, deafness, coma, and death.

Meningitis and encephalitis can be caused by many different types of microbial pathogens. However, these conditions can also arise from noninfectious causes such as head trauma, some cancers, and certain drugs that trigger inflammation. To determine whether the inflammation is caused by a pathogen, a lumbar puncture is performed to obtain a sample of CSF. If the CSF contains increased levels of white blood cells and abnormal glucose and protein levels, this indicates that the inflammation is a response to an infectioninflinin.

![]()

- What are the two types of inflammation that can impact the CNS?

- Why do both forms of inflammation have such serious consequences?

Micro Connections

Guillain-Barré Syndrome

Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) is a rare condition that can be preceded by a viral or bacterial infection that results in an autoimmune reaction against myelinated nerve cells. The destruction of the myelin sheath around these neurons results in a loss of sensation and function. The first symptoms of this condition are tingling and weakness in the affected tissues. The symptoms intensify over a period of several weeks and can culminate in complete paralysis. Severe cases can be life-threatening. Infections by several different microbial pathogens, including Campylobacter jejuni (the most common risk factor), cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, varicella- zoster virus, Mycoplasma pneumoniae,[1] and Zika virus[2] have been identified as triggers for GBS. Anti-myelin antibodies from patients with GBS have been demonstrated to also recognize C. jejuni. It is possible that cross- reactive antibodies, antibodies that react with similar antigenic sites on different proteins, might be formed during an infection and may lead to this autoimmune response. GBS is solely identified by the appearance of clinical symptoms. There are no other diagnostic tests available. Fortunately, most cases spontaneously resolve within a few months with few permanent effects, as there is no available vaccine. GBS can be treated by plasmapheresis. In this procedure, the patient’s plasma is filtered from their blood, removing autoantibodies.

- Yuki, Nobuhiro and Hans-Peter Hartung, “Guillain–Barré Syndrome,” New England Journal of Medicine 366, no. 24 (2012): 2294-304. ↵

- Cao-Lormeau, Van-Mai, Alexandre Blake, Sandrine Mons, Stéphane Lastère, Claudine Roche, Jessica Vanhomwegen, Timothée Dub et al., “Guillain-Barré Syndrome Outbreak Associated with Zika Virus Infection in French Polynesia: A Case-Control Study,” The Lancet 387, no. 10027 (2016): 1531-9. ↵