18.3 Bacterial Infections of the Reproductive System

Learning Objectives

- Identify the most common bacterial pathogens that can cause infections of the reproductive system

- Compare the major characteristics of specific bacterial diseases affecting the reproductive system

In addition to infections of the urinary tract, bacteria commonly infect the reproductive tract. As with the urinary tract, parts of the reproductive system closest to the external environment are the most likely sites of infection. Often, the same microbes are capable of causing urinary tract and reproductive tract infections.

Bacterial Vaginitis and Vaginosis

Inflammation of the vagina is called vaginitis, often caused by a bacterial infection. It is also possible to have an imbalance in the normal vaginal microbiota without inflammation called bacterial vaginosis (BV). Vaginosis may be asymptomatic or may cause mild symptoms such as a thin, white-to-yellow, homogeneous vaginal discharge, burning, odor, and itching. The major causative agent is Gardnerella vaginalis, a gram-variable to gram-negative pleomorphic bacterium. The disease is usually self-limiting, although antibiotic treatment is recommended if symptoms develop.

G. vaginalis appears to be more virulent than other vaginal bacterial species potentially associated with BV. Like Lactobacillus spp., G. vaginalis is part of the normal vaginal microbiota, but when the population of Lactobacillus spp. decreases and the vaginal pH increases, G. vaginalis flourishes, causing vaginosis by attaching to vaginal epithelial cells and forming a thick protective biofilm. G. vaginalis also produces a cytotoxin called vaginolysin that lyses vaginal epithelial cells and red blood cells.

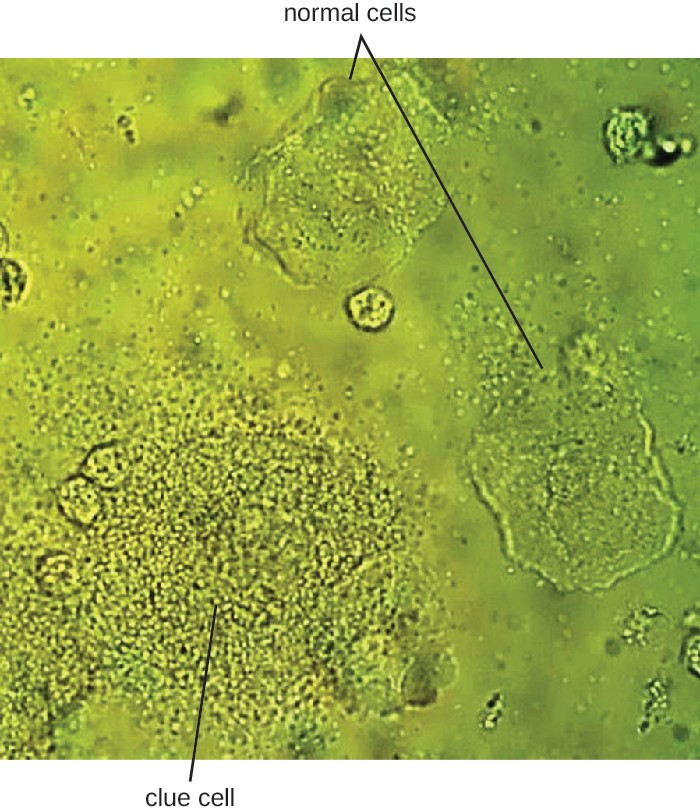

Since G. vaginalis can also be isolated from healthy women, the “gold standard” for the diagnosis of BV is direct examination of vaginal secretions and not the culture of G. vaginalis. Diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis from vaginal secretions can be accurately made in three ways. The first is to use a DNA probe. The second method is to assay for sialidase activity, an enzyme produced by G. vaginalis and other bacteria associated with vaginosis. The third method is to assess gram-stained vaginal smears for microscopic morphology and relative numbers and types of bacteria, squamous epithelial cells, and leukocytes. By examining slides prepared from vaginal swabs, it is possible to distinguish lactobacilli (long, gram- positive rods) from other gram-negative species responsible for BV. A shift in predominance from gram-positive bacilli to gram-negative coccobacilli can indicate BV. Additionally, the slide may contain so-called clue cells, which are epithelial cells that appear to have a granular or stippled appearance due to bacterial cells attached to their surface (Figure 18.5). Presumptive diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis can involve an assessment of clinical symptoms and evaluation of vaginal fluids using Amsel’s diagnostic criteria which include 3 out of 4 of the following characteristics:

- white to yellow discharge;

- a fishy odor, most noticeable when 10% KOH is added;

- pH greater than 4.5;

- the presence of clue cells.

Treatment is often unnecessary because the infection often clears on its own. However, in some cases, antibiotics such as topical or oral clindamycin or metronidazole may be prescribed. Alternative treatments include oral tinidazole or clindamycin ovules (vaginal suppositories).

![]()

- Explain the difference between vaginosis and vaginitis.

- What organisms are responsible for vaginosis and what organisms typically hold it at bay?

Gonorrhea

Also known as the clap, gonorrhea is a common sexually transmitted disease of the reproductive system that is especially prevalent in individuals between the ages of 15 and 24. It is caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae, often called gonococcus or GC, which have fimbriae that allow the cells to attach to epithelial cells. It also has a type of lipopolysaccharide endotoxin called lipooligosaccharide as part of the outer membrane structure that enhances its pathogenicity. In addition to causing urethritis, N. gonorrhoeae can infect other body tissues such as the skin, meninges, pharynx, and conjunctiva.

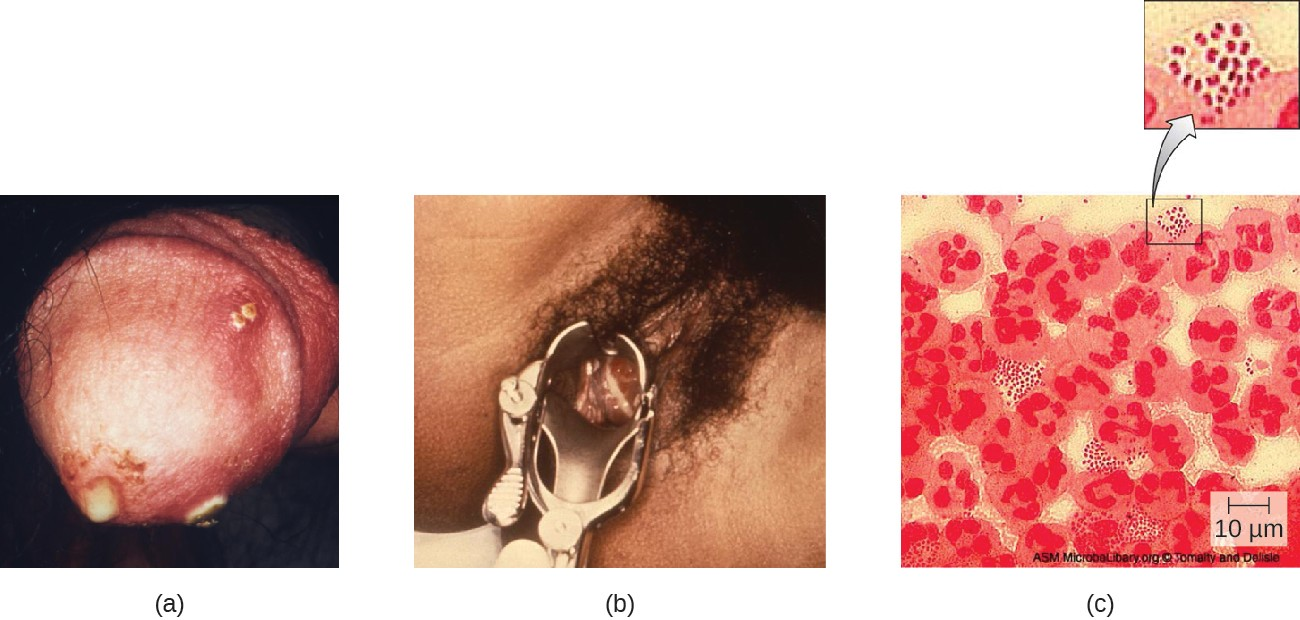

Many infected individuals (both men and women) are asymptomatic carriers of gonorrhea. When symptoms do occur, they manifest differently in males and females. Males may develop pain and burning during urination and discharge from the penis that may be yellow, green, or white (Figure 18.6). Less commonly, the testicles may become swollen or tender. Over time, these symptoms can increase and spread. In some cases, chronic infection develops. The disease can also develop in the rectum, causing symptoms such as discharge, soreness, bleeding, itching, and pain (especially in association with bowel movements).

Women may develop pelvic pain, discharge from the vagina, intermenstrual bleeding (i.e., bleeding not associated with normal menstruation), and pain or irritation associated with urination. As with men, the infection can become chronic. In women, however, chronic infection can cause increases in menstrual flow. Rectal infection can also occur, with the symptoms previously described for men. Infections that spread to the endometrium and fallopian tubes can cause pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), characterized by pain in the lower abdominal region, dysuria, vaginal discharge, and fever. PID can also lead to infertility through scarring and blockage of the fallopian tubes (salpingitis); it may also increase the risk of a life-threatening ectopic pregnancy, which occurs when a fertilized egg begins developing somewhere other than the uterus (e.g., in the fallopian tube or ovary).

When a gonorrhea infection disseminates throughout the body, serious complications can develop. The infection may spread through the blood (bacteremia) and affect organs throughout the body, including the heart (gonorrheal endocarditis), joints (gonorrheal arthritis), and meninges encasing the brain (meningitis).

Urethritis caused by N. gonorrhoeae can be difficult to treat due to antibiotic resistance. Some strains have developed resistance to the fluoroquinolones, so cephalosporins are often a first choice for treatment. Because co-infection with C. trachomatis is common, the CDC recommends treating with a combination regimen of ceftriaxone and azithromycin. Treatment of sexual partners is also recommended to avoid reinfection and spread of infection to others.[1]

![]()

- What are some of the serious consequences of a gonorrhea infection?

- What organism commonly coinfects with N. gonorrhoeae?

Micro Connections

Antibiotic Resistance in Neisseria

Antibiotic resistance in many pathogens is steadily increasing, causing serious concern throughout the public health community. Increased resistance has been especially notable in some species, such as Neisseria gonorrhoeae. The CDC monitors the spread of antibiotic resistance in N. gonorrhoeae, which it classifies as an urgent threat, and makes recommendations for treatment. So far, N. gonorrhoeae has shown resistance to cefixime (a cephalosporin), ceftriaxone (another cephalosporin), azithromycin, and tetracycline. Resistance to tetracycline is the most common, and was seen in 188,600 cases of gonorrhea in 2011 (out of a total 820,000 cases). In 2011, some 246,000 cases of gonorrhea involved strains of N. gonorrhoeae that were resistant to at least one antibiotic.[2] These resistance genes are spread by plasmids, and a single bacterium may be resistant to multiple antibiotics. The CDC currently recommends treatment with two medications, ceftriaxone and azithromycin, to attempt to slow the spread of resistance. If resistance to cephalosporins increases, it will be extremely difficult to control the spread of N. gonorrhoeae.

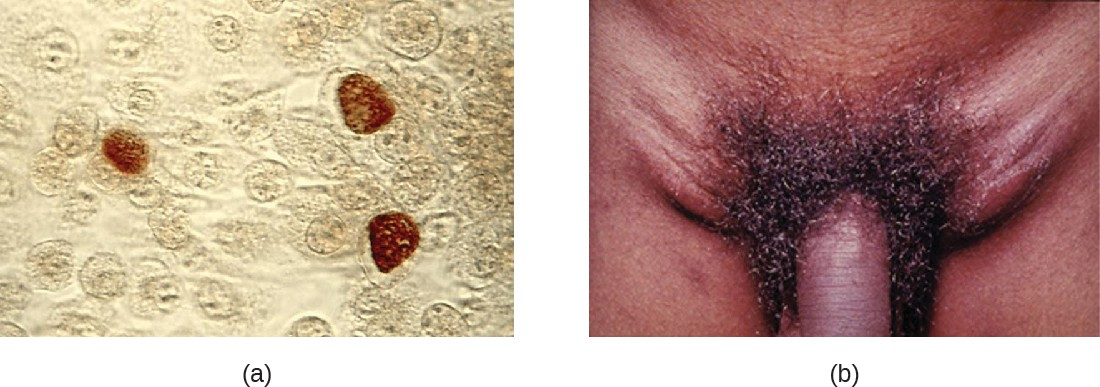

Chlamydia

Chlamydia trachomatis is the causative agent of the STI chlamydia (Figure 18.7). While many Chlamydia infections are asymptomatic, chlamydia is a major cause of nongonococcal urethritis (NGU) and may also cause epididymitis and orchitis in men. In women, chlamydia infections can cause urethritis, salpingitis, and PID. In addition, chlamydial infections may be associated with an increased risk of cervical cancer.

Because chlamydia is widespread, often asymptomatic, and has the potential to cause substantial complications, routine screening is recommended for sexually active women who are under age 25, at high risk (i.e., not in a monogamous relationship), or beginning prenatal care.

Urogenital infections caused by C. trachomatis can be treated using antibiotics.

![]()

- Compare the signs and symptoms of chlamydia infection in men and women.

Disease Profile

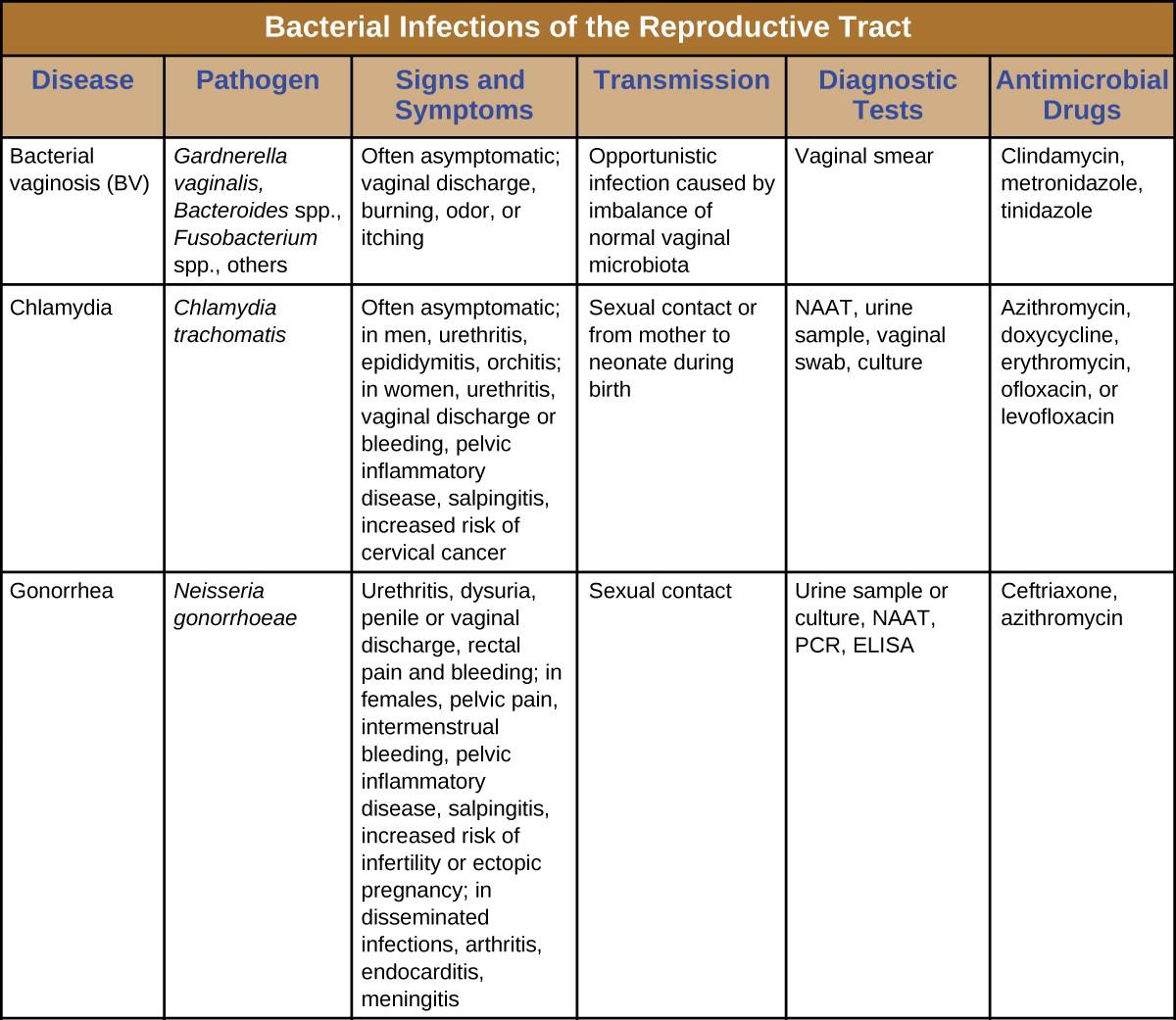

Bacterial Reproductive Tract Infections

Many bacterial infections affecting the reproductive system are transmitted through sexual contact, but some can be transmitted by other means. In the United States, gonorrhea and chlamydia are common illnesses with incidences of about 350,000 and 1.44 million, respectively, in 2014. Syphilis is a rarer disease with an incidence of 20,000 in 2014. Chancroid is exceedingly rare in the United States with only six cases in 2014 and a median of 10 cases per year for the years 2010–2014.[3] Figure 18.8 summarizes bacterial infections of the reproductive tract.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “2015 Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines: Gonococcal Infections,” 2015. http://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/gonorrhea.htm. ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2013,” 2013. http://www.cdc.gov/ drugresistance/pdf/ar-threats-2013-508.pdf. ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “2014 Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance,” 2015. http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats14/default.htm. ↵