18.5 Fungal Infections of the Reproductive System

Learning Objectives

- Summarize the important characteristics of vaginal candidiasis

Fungal Infection

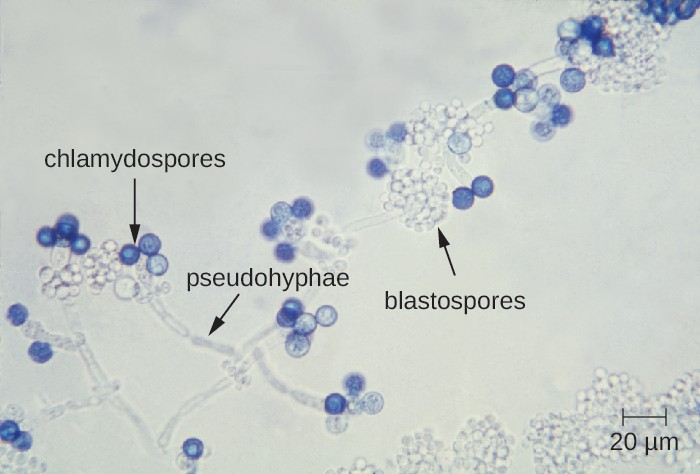

Only one major fungal pathogen affects the urogenital system. Candida is a genus of fungi capable of existing in a yeast form or as a multicellular fungus. Candida spp. are commonly found in the normal, healthy microbiota of the skin, gastrointestinal tract, respiratory system, and female urogenital tract (Figure 18.14). They can be pathogenic due to their ability to adhere to and invade host cells, form biofilms, secrete hydrolases (e.g., proteases, phospholipases, and lipases) that assist in their spread through tissues, and change their phenotypes to protect themselves from the immune system. However, they typically only cause disease in the female reproductive tract under conditions that compromise the host’s defenses. While there are at least 20 Candida species of clinical importance, C. albicans is the species most commonly responsible for fungal vaginitis.

As discussed earlier, lactobacilli in the vagina inhibit the growth of other organisms, including bacteria and Candida, but disruptions can allow Candida to increase in numbers. Typical disruptions include antibiotic therapy, illness (especially diabetes), pregnancy, and the presence of transient microbes. Immunosuppression can also play a role, and the severe immunosuppression associated with HIV infection often allows Candida to thrive. This can cause genital or vaginal candidiasis, a condition characterized by vaginitis and commonly known as a yeast infection. When a yeast infection develops, inflammation occurs along with symptoms of pruritus (itching), a thick white or yellow discharge, and odor.

Other forms of candidiasis include cutaneous candidiasis (see Mycoses of the Skin) and oral thrush (see Microbial Diseases of the Mouth and Oral Cavity). Although Candida spp. are found in the normal microbiota, Candida spp. may also be transmitted between individuals. Sexual contact is a common mode of transmission, although candidiasis is not considered an STI.

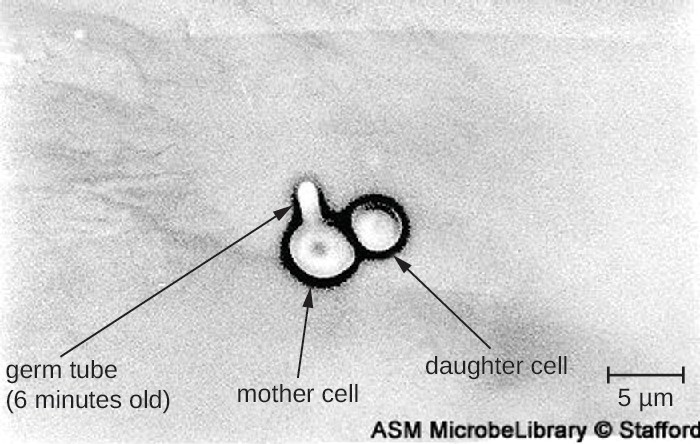

Diagnosis of vaginal candidiasis can be made using microscopic evaluation of vaginal secretions to determine whether there is an excess of Candida. Culturing approaches are less useful because Candida is part of the normal microbiota and will regularly appear. It is also easy to contaminate samples with Candida because it is so common, so care must be taken to handle clinical material appropriately. Samples can be refrigerated if there is a delay in handling. Candida is a dimorphic fungus, so it does not only exist in a yeast form; cultivation can be used to identify chlamydospores and pseudohyphae, which develop from germ tubes (Figure 18.15). The presence of the germ tube can be used in a diagnostic test in which cultured yeast cells are combined with rabbit serum and observed after a few hours for the presence of germ tubes. Molecular tests are also available if needed. The Affirm VPII Microbial Identification Test, for instance, tests simultaneously for the vaginal microbes C. albicans, G. vaginalis (see Bacterial Infections of the Urinary System), and Trichomonas vaginalis (see Protozoan Infections of the Urogenital System).

Topical antifungal medications for vaginal candidiasis include butoconazole, miconazole, clotrimazole, tioconazole, and nystatin. Oral treatment with fluconazole can be used. There are often no clear precipitating factors for infection, so prevention is difficult.

![]()

- What factors can lead to candidiasis?

- How is candidiasis typically diagnosed?