4.3 Fungi

Learning Objectives

- Explain why the study of fungi such as yeast and molds is within the discipline of microbiology

- Describe the unique characteristics of fungi

- Describe examples of asexual and sexual reproduction of fungi

- Compare the major groups of fungi in this chapter

- Classify fungal organisms according to major groups

The fungi comprise a diverse group of organisms that are heterotrophic and typically saprozoic. In addition to the well-known macroscopic fungi (such as mushrooms and molds), many unicellular yeasts and spores of macroscopic fungi are microscopic. For this reason, fungi are included within the field of microbiology.

Fungi are important to humans in a variety of ways. Both microscopic and macroscopic fungi have medical relevance, with some pathogenic species that can cause mycoses (illnesses caused by fungi). Some pathogenic fungi are opportunistic, meaning that they mainly cause infections when the host’s immune defenses are compromised and do not normally cause illness in healthy individuals. Fungi are important in other ways. They act as decomposers in the environment, and they are critical for the production of certain foods such as cheeses. Fungi are also major sources of antibiotics, such as penicillin from the fungus Penicillium.

Characteristics of Fungi

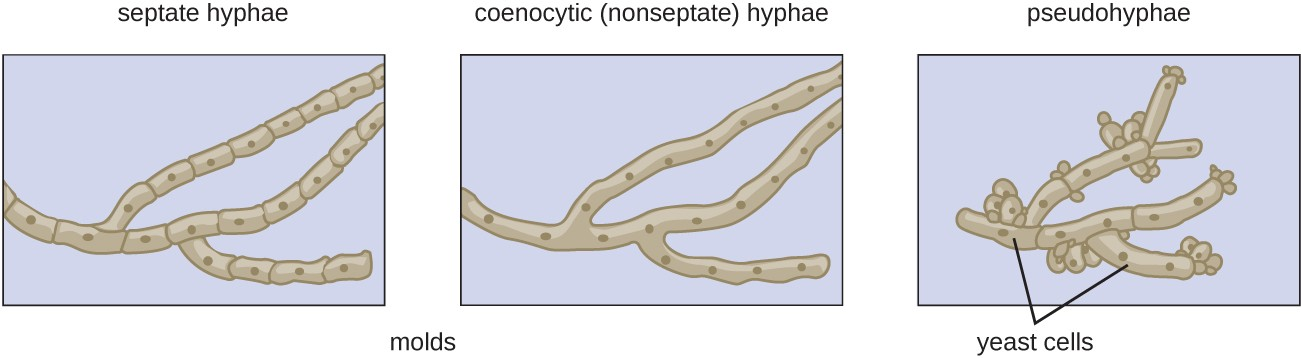

Fungi have well-defined characteristics that set them apart from other organisms. Most multicellular fungal bodies, commonly called molds, are made up of filaments called hyphae. Hyphae can form a tangled network called a mycelium and form the thallus (body) of fleshy fungi. Hyphae that have walls between the cells are called septate hyphae; hyphae that lack walls and cell membranes between the cells are called nonseptate or coenocytic hyphae. (Figure 4.14).

In contrast to molds, yeasts are unicellular fungi. The budding yeasts reproduce asexually by budding off a smaller daughter cell; the resulting cells may sometimes stick together as a short chain or pseudohypha (Figure 4.14).

Some fungi are dimorphic, having more than one appearance during their life cycle. These dimorphic fungi may be able to appear as yeasts or molds, which can be important for infectivity. They are capable of changing their appearance in response to environmental changes such as nutrient availability or fluctuations in temperature, growing as a mold, for example, at 25 °C (77 °F), and as yeast cells at 37 °C (98.6 °F). This ability helps dimorphic fungi to survive in diverse environments.

There are notable unique features in fungal cell walls and membranes. Fungal cell walls contain chitin, as opposed to the cellulose found in the cell walls of plants and many protists. Additionally, whereas animals have cholesterol in their cell membranes, fungal cell membranes have different sterols called ergosterols. Ergosterols are often exploited as targets for antifungal drugs.

Fungal life cycles are unique and complex. Fungi reproduce sexually either through cross- or self-fertilization.

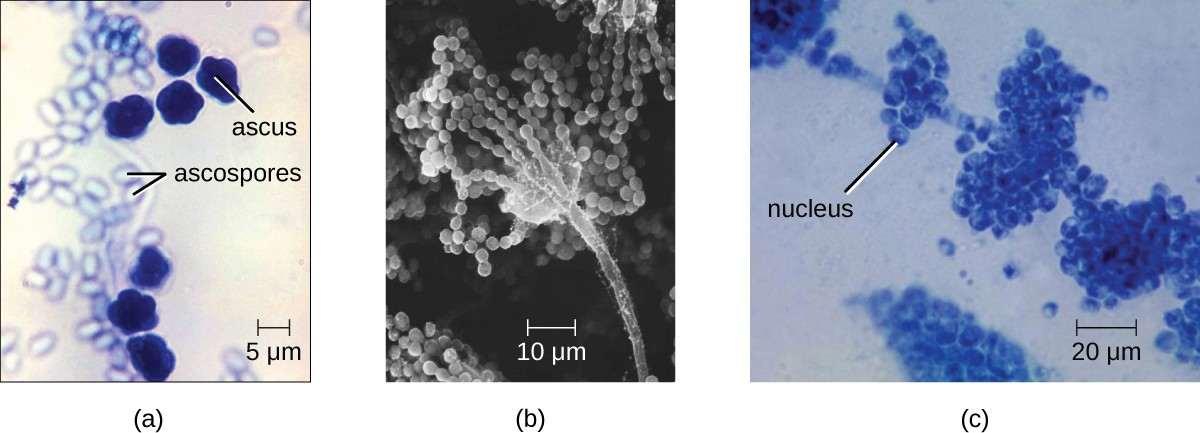

Fungi may also exhibit asexual reproduction budding, fragmentation of hyphae, and formation of asexual spores. These spores are specialized cells that, depending on the organism, may have unique characteristics for survival, reproduction, and dispersal. Fungi exhibit several types of asexual spores and these can be important in classification (Figure 4.15).

![]()

- Is a dimorphic fungus a yeast or a mold? Explain.

Fungal Diversity

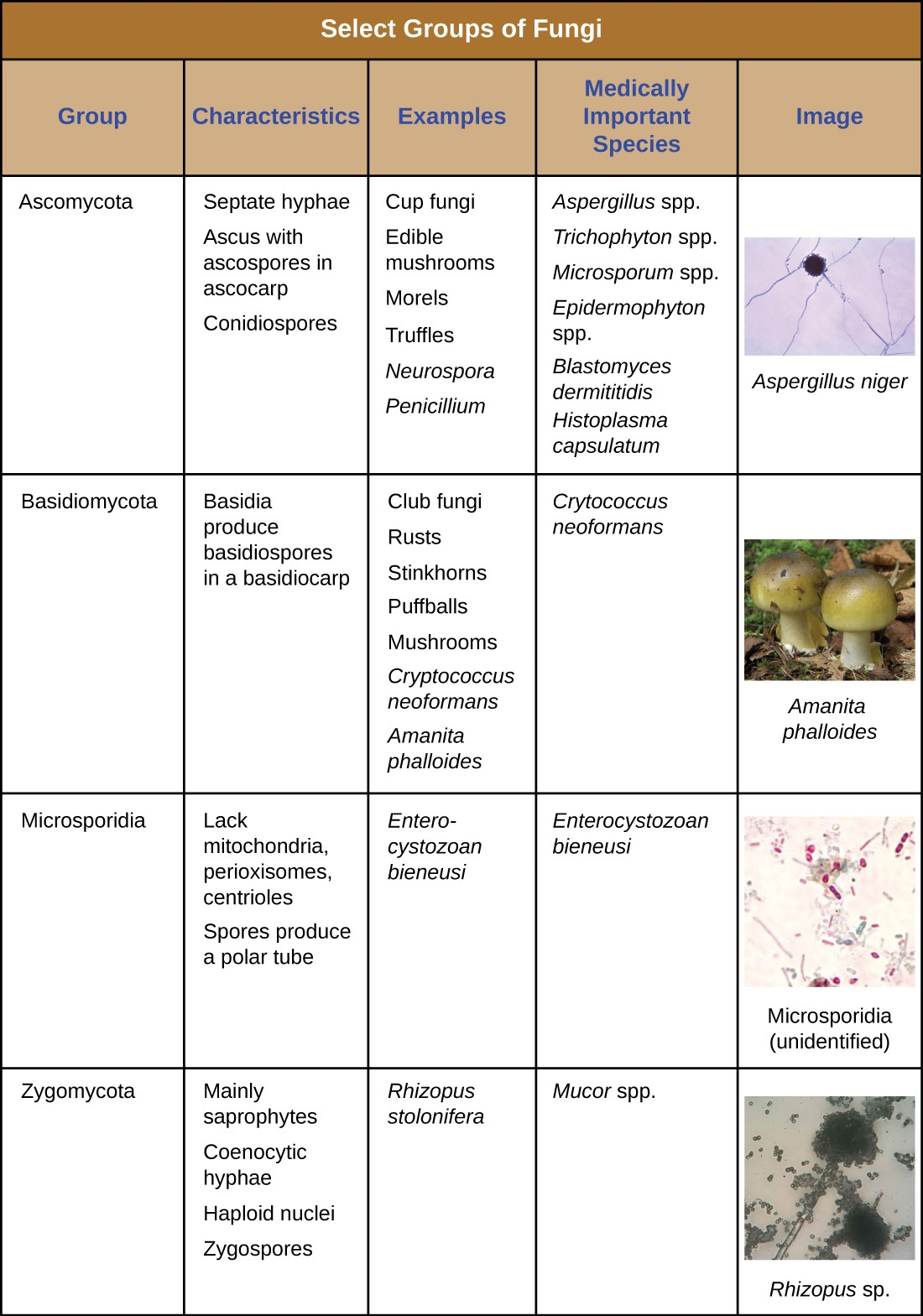

The fungi are very diverse, comprising seven major groups. Not all of the seven groups contain pathogens. Some of these groups are generally associated with plants and include plant pathogens. Because of their medical importance, we will focus on Zygomycota, Ascomycota, Basidiomycota, and Microsporidia. Figure 4.17 summarizes the characteristics of these medically important groups of fungi.

The Zygomycota (zygomycetes) are mainly saprophytes with coenocytic hyphae and haploid nuclei. They use sporangiospores for asexual reproduction. The group name comes from the zygospores that they use for sexual reproduction, which have hard walls formed from the fusion of reproductive cells from two individuals. Zygomycetes are important for food science and as crop pathogens.

The Ascomycota include fungi that are used as food (edible mushrooms, morels, and truffles), others that are common causes of food spoilage (bread molds and plant pathogens), and still others that are human pathogens. Some genera of Ascomycota use sexually produced ascospores (Figure 4.16) as well as asexual spores called conidia, but sexual phases have not been discovered or described for others. Some produce an ascus containing ascospores within an ascocarp.

Examples of the Ascomycota include several bread molds and minor pathogens, as well as species capable of causing more serious mycoses. The fungus Aspergillus flavus, a contaminant of nuts and stored grains, produces an aflatoxin that is both a toxin and the most potent known natural carcinogen. Penicillium produces the antibiotic penicillin. Many species of ascomycetes are medically important, causing a range of conditions such as skin infections, respiratory infections, and vaginal yeast infections.

The Basidiomycota (basidiomycetes) are fungi that produce basidiospores (spores produced through budding) within fruiting bodies called basidiocarps. They are important as decomposers and as food. This group includes rusts, stinkhorns, puffballs, and mushrooms. Several species are of clinical importance, causing lung infections or other health issues.

Finally, the Microsporidia are unicellular fungi that are obligate intracellular parasites. They lack mitochondria, peroxisomes, and centrioles, but their spores release a unique polar tubule that pierces the host cell membrane to allow the fungus to gain entry into the cell. A number of microsporidia are human pathogens, and infections with microsporidia are called microsporidiosis.

![]()

- Which group of fungi appears to be associated with the greatest number of human diseases?