18.6 Protozoan Infections of the Urogenital System

Learning Objectives

- Identify the most common protozoan pathogen that causes infections of the reproductive system

- Summarize the important characteristics of trichomoniasis

Protozoan Infection

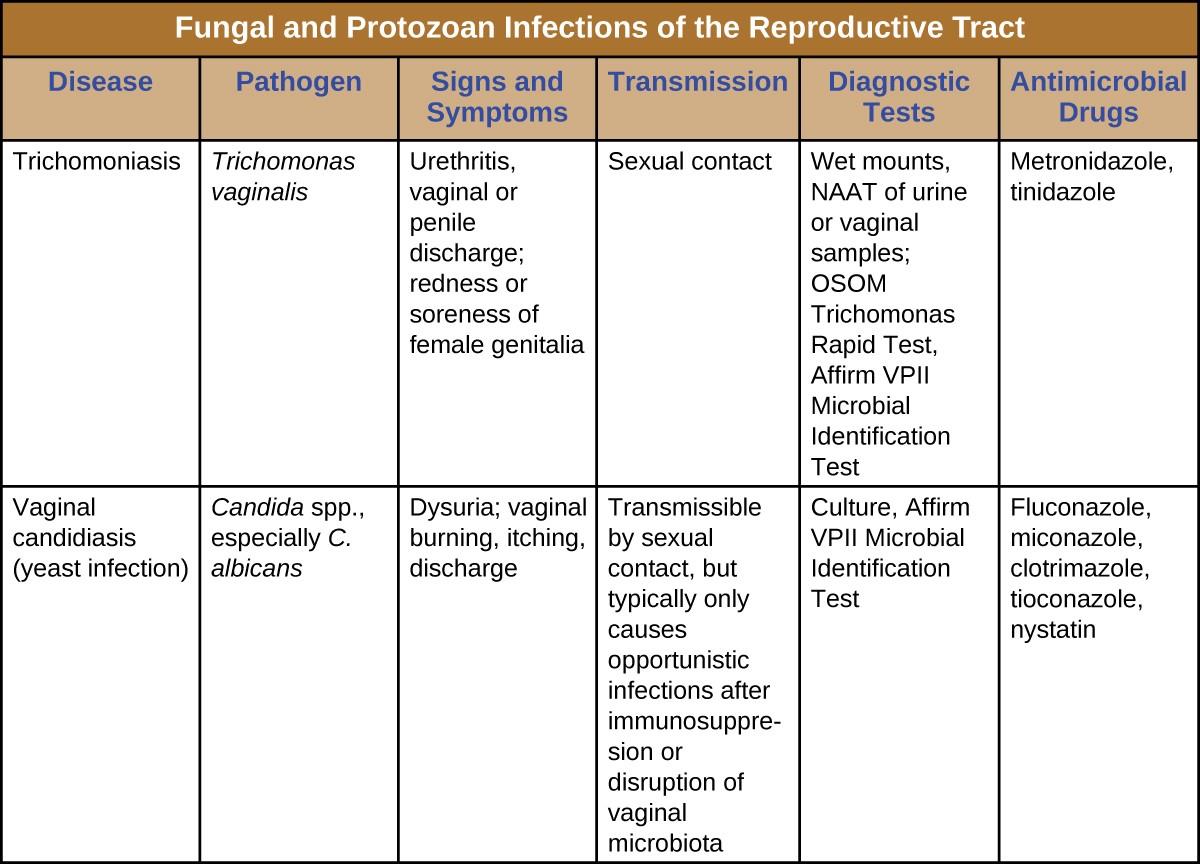

Only one major protozoan species causes infections in the urogenital system. Trichomoniasis, or “trich,” is the most common nonviral STI and is caused by a flagellated protozoan Trichomonas vaginalis. T. vaginalis has an undulating membrane and, generally, an amoeboid shape when attached to cells in the vagina. In culture, it has an oval shape.

T. vaginalis is commonly found in the normal microbiota of the vagina. As with other vaginal pathogens, it can cause vaginitis when there is disruption to the normal microbiota. It is found only as a trophozoite and does not form cysts. T. vaginalis can adhere to cells using adhesins such as lipoglycans; it also has other cell-surface virulence factors, including tetraspanins that are involved in cell adhesion, motility, and tissue invasion. In addition, T. vaginalis is capable of phagocytosing other microbes of the normal microbiota, contributing to the development of an imbalance that is favorable to infection.

Both men and women can develop trichomoniasis. Men are generally asymptomatic, and although women are more likely to develop symptoms, they are often asymptomatic as well. When symptoms do occur, they are characteristic of urethritis. Men experience itching, irritation, discharge from the penis, and burning after urination or ejaculation. Women experience dysuria; itching, burning, redness, and soreness of the genitalia; and vaginal discharge. The infection may also spread to the cervix. Infection increases the risk of transmitting or acquiring HIV and is associated with pregnancy complications such as preterm birth.

Microscopic evaluation of wet mounts is an inexpensive and convenient method of diagnosis, but the sensitivity of this method is low (Figure 18.16). Nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) is preferred due to its high sensitivity. Using wet mounts and then NAAT for those who initially test negative is one option to improve sensitivity.

Samples may be obtained for NAAT using urine, vaginal, or endocervical specimens for women and with urine and urethral swabs for men. It is also possible to use other methods such as the OSOM Trichomonas Rapid Test (an immunochromatographic test that detects antigen) and a DNA probe test for multiple species associated with vaginitis (the Affirm VPII Microbial Identification Test discussed in section 23.5).[1] T. vaginalis is sometimes detected on a Pap test, but this is not considered diagnostic due to high rates of false positives and negatives. The recommended treatment for trichomoniasis is oral metronidazole or tinidazole. Sexual partners should be treated as well.

![]()

- What are the symptoms of trichomoniasis?

Eye on Ethics

STIs and Privacy

For many STIs, it is common to contact and treat sexual partners of the patient. This is especially important when a new illness has appeared, as when HIV became more prevalent in the 1980s. But to contact sexual partners, it is necessary to obtain their personal information from the patient. This raises difficult questions. In some cases, providing the information may be embarrassing or difficult for the patient, even though withholding such information could put their sexual partner(s) at risk.

Legal considerations further complicate such situations. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPPA), passed into law in 1996, sets the standards for the protection of patient information. It requires businesses that use health information, such as insurance companies and healthcare providers, to maintain strict confidentiality of patient records. Contacting a patient’s sexual partners may therefore violate the patient’s privacy rights if the patient’s diagnosis is revealed as a result.

From an ethical standpoint, which is more important: the patient’s privacy rights or the sexual partner’s right to know that they may be at risk of a sexually transmitted disease? Does the answer depend on the severity of the disease or are the rules universal? Suppose the physician knows the identity of the sexual partner but the patient does not want that individual to be contacted. Would it be a violation of HIPPA rules to contact the individual without the patient’s consent?

Questions related to patient privacy become even more complicated when dealing with patients who are minors. Adolescents may be reluctant to discuss their sexual behavior or health with a health professional, especially if they believe that healthcare professionals will tell their parents. This leaves many teens at risk of having an untreated infection or of lacking the information to protect themselves and their partners. On the other hand, parents may feel that they have a right to know what is going on with their child. How should physicians handle this? Should parents always be told even if the adolescent wants confidentiality? Does this affect how the physician should handle notifying a sexual partner?

- Association of Public Health Laboratories. “Advances in Laboratory Detection of Trichomonas vaginalis,” 2013. http://www.aphl.org/ AboutAPHL/publications/Documents/ID_2013August_Advances-in-Laboratory-Detection-of-Trichomonas-vaginalis.pdf. ↵