16.1 Anatomy and Normal Microbiota of the Skin and Eyes

Learning Objectives

- Describe the major anatomical features of the skin and eyes

- Compare and contrast the microbiomes of various body sites, such as the hands, back, feet, and eyes

- Explain how microorganisms overcome defenses of skin and eyes in order to cause infection

- Describe general signs and symptoms of disease associated with infections of the skin and eyes

Human skin is an important part of the innate immune system. In addition to serving a wide range of other functions, the skin serves as an important barrier to microbial invasion. Not only is it a physical barrier to penetration of deeper tissues by potential pathogens, but it also provides an inhospitable environment for the growth of many pathogens. In this section, we will provide a brief overview of the anatomy and normal microbiota of the skin and eyes, along with general symptoms associated with skin and eye infections.

Layers of the Skin

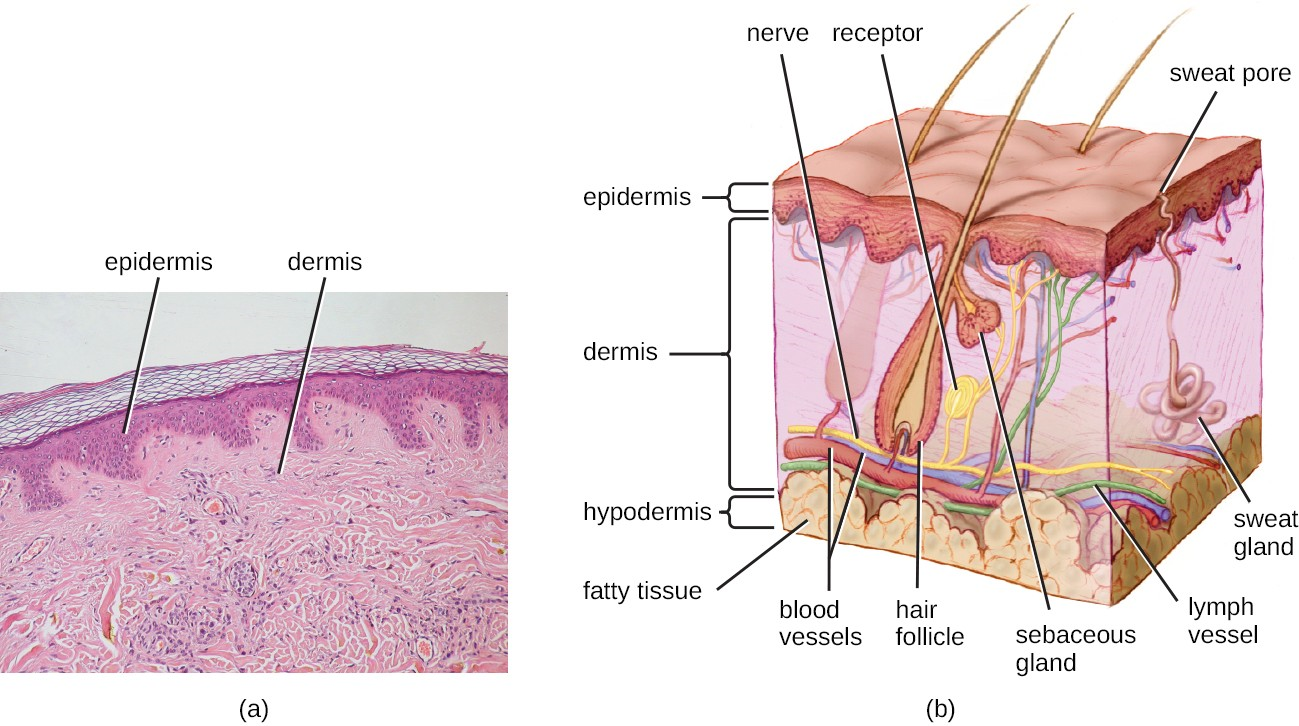

Human skin is made up of several layers and sublayers. The two main layers are the epidermis and the dermis. These layers cover a third layer of tissue called the hypodermis, which consists of fibrous and adipose connective tissue (Figure 16.2).

The epidermis is the outermost layer of the skin, and it is relatively thin. The exterior surface of the epidermis, called the stratum corneum, primarily consists of dead skin cells. This layer of dead cells limits direct contact between the outside world and live cells. The stratum corneum is rich in keratin, a tough, fibrous protein that is also found in hair and nails. Keratin helps make the outer surface of the skin relatively tough and waterproof. It also helps to keep the surface of the skin dry, which reduces microbial growth. However, some microbes are still able to live on the surface of the skin, and some of these can be shed with dead skin cells in the process of desquamation, which is the shedding and peeling of skin that occurs as a normal process but that may be accelerated when infection is present.

Beneath the epidermis lies a thicker skin layer called the dermis. The dermis contains connective tissue and embedded structures such as blood vessels, nerves, and muscles. Structures called hair follicles (from which hair grows) are located within the dermis, even though much of their structure consists of epidermal tissue. The dermis also contains the two major types of glands found in human skin: sweat glands (tubular glands that produce sweat) and sebaceous glands (which are associated with hair follicles and produce sebum, a lipid-rich substance containing proteins and minerals).

Perspiration (sweat) provides some moisture to the epidermis, which can increase the potential for microbial growth. For this reason, more microbes are found on the regions of the skin that produce the most sweat, such as the skin of the underarms and groin. However, in addition to water, sweat also contains substances that inhibit microbial growth, such as salts, lysozyme, and antimicrobial peptides. Sebum also serves to protect the skin and reduce water loss. Although some of the lipids and fatty acids in sebum inhibit microbial growth, sebum contains compounds that provide nutrition for certain microbes.

![]()

- How does desquamation help with preventing infections?

Normal Microbiota of the Skin

The skin is home to a wide variety of normal microbiota, consisting of commensal organisms that derive nutrition from skin cells and secretions such as sweat and sebum. The normal microbiota of skin tends to inhibit transient- microbe colonization by producing antimicrobial substances and outcompeting other microbes that land on the surface of the skin. This helps to protect the skin from pathogenic infection.

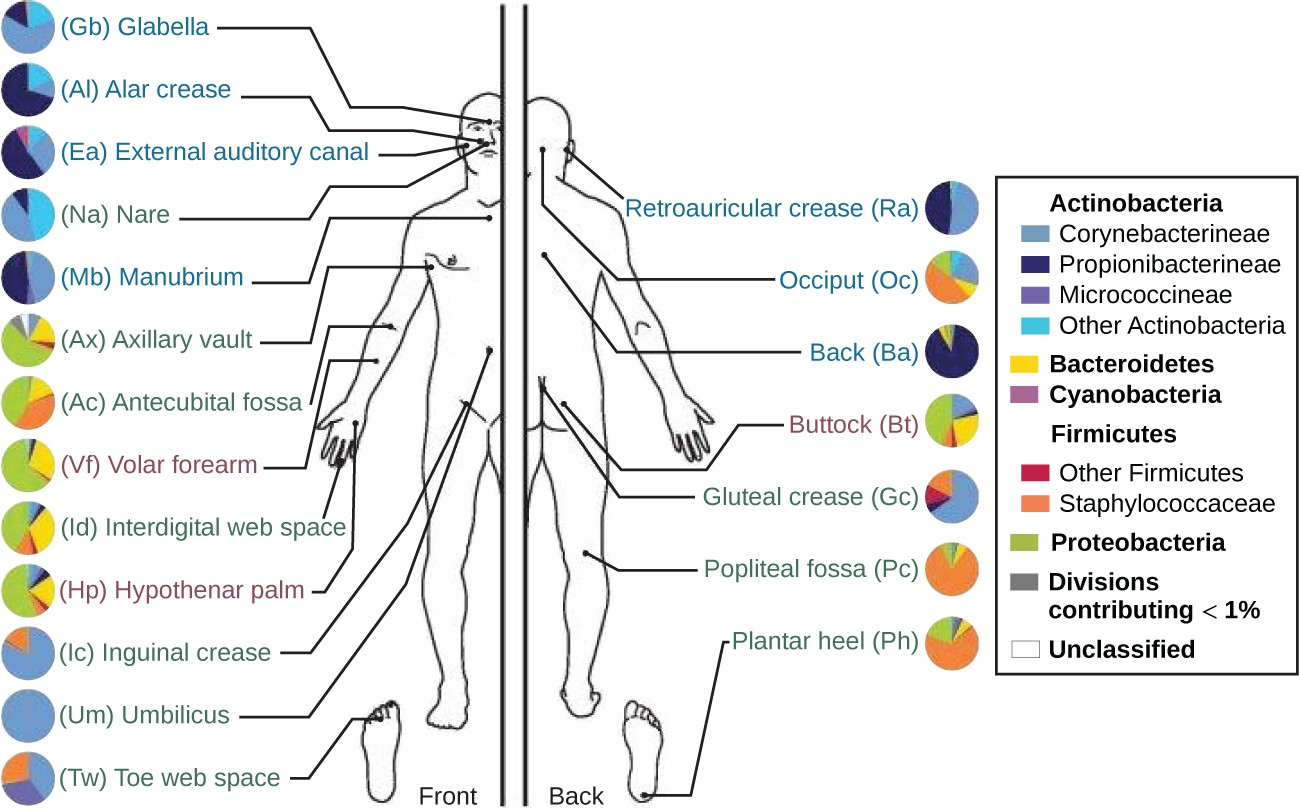

The skin’s properties differ from one region of the body to another, as does the composition of the skin’s microbiota. The availability of nutrients and moisture partly dictates which microorganisms will thrive in a particular region of the skin. Relatively moist skin, such as that of the nares (nostrils) and underarms, has a much different microbiota than the dryer skin on the arms, legs, hands, and top of the feet. Some areas of the skin have higher densities of sebaceous glands. These sebum-rich areas, which include the back, the folds at the side of the nose, and the back of the neck, harbor distinct microbial communities that are less diverse than those found on other parts of the body.

Different types of bacteria dominate the dry, moist, and sebum-rich regions of the skin. The most abundant microbes typically found in the dry and sebaceous regions are Betaproteobacteria and Propionibacteria, respectively. In the moist regions, Corynebacterium and Staphylococcus are most commonly found (Figure 16.3). Viruses and fungi are also found on the skin, with Malassezia being the most common type of fungus found as part of the normal microbiota. The role and populations of viruses in the microbiota, known as viromes, are still not well understood, and there are limitations to the techniques used to identify them.

![]()

- What are the four most common bacteria that are part of the normal skin microbiota?

Infections of the Skin

While the microbiota of the skin can play a protective role, it can also cause harm in certain cases. Often, an opportunistic pathogen residing in the skin microbiota of one individual may be transmitted to another individual more susceptible to an infection. For example, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) can often take upresidence in the nares of health care workers and hospital patients; though harmless on intact, healthy skin, MRSA can cause infections if introduced into other parts of the body, as might occur during surgery or via a post-surgical incision or wound. This is one reason why clean surgical sites are so important.

Injury or damage to the skin can allow microbes to enter deeper tissues, where nutrients are more abundant and the environment is more conducive to bacterial growth. Wound infections are common after a puncture or laceration that damages the physical barrier of the skin. Microbes may infect structures in the dermis, such as hair follicles and glands, causing a localized infection, or they may reach the bloodstream, which can lead to a systemic infection.

In some cases, infectious microbes can cause a variety of rashes or lesions that differ in their physical characteristics. These rashes can be the result of inflammation reactions or direct responses to toxins produced by the microbes. Table 16.1 lists some of the medical terminology used to describe skin lesions and rashes based on their characteristics. It is important to note that many different diseases can lead to skin conditions of very similar appearance; thus the terms used in the table are generally not exclusive to a particular type of infection or disease.

|

Term |

Definition |

|---|---|

|

abscess |

localized collection of pus |

|

bulla (pl., bullae) |

fluid-filled blister no more than 5 mm in diameter |

|

carbuncle |

deep, pus-filled abscess generally formed from multiple furuncles |

|

crust |

dried fluids from a lesion on the surface of the skin |

|

cyst |

encapsulated sac filled with fluid, semi-solid matter, or gas, typically located just below the upper layers of skin |

|

folliculitis |

a localized rash due to inflammation of hair follicles |

|

furuncle (boil) |

pus-filled abscess due to infection of a hair follicle |

|

macules |

smooth spots of discoloration on the skin |

|

papules |

small raised bumps on the skin |

|

pseudocyst |

lesion that resembles a cyst but with a less defined boundary |

|

purulent |

pus-producing; suppurative |

|

pustules |

fluid- or pus-filled bumps on the skin |

|

pyoderma |

any suppurative (pus-producing) infection of the skin |

|

suppurative |

producing pus; purulent |

|

ulcer |

break in the skin; open sore |

|

vesicle |

small, fluid-filled lesion |

|

wheal |

swollen, inflamed skin that itches or burns, such as from an insect bite |

- How can asymptomatic health care workers transmit bacteria such as MRSA to patients?

Anatomy and Microbiota of the Eye

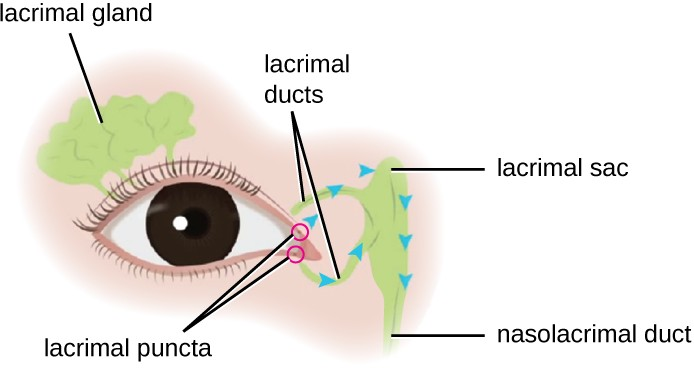

Although the eye and skin have distinct anatomy, they are both in direct contact with the external environment. An important component of the eye is the nasolacrimal drainage system, which serves as a conduit for the fluid of the eye, called tears. Tears flow from the external eye to the nasal cavity by the lacrimal apparatus, which is composed of the structures involved in tear production (Figure 16.4). The lacrimal gland, above the eye, secretes tears to keep the eye moist. There are two small openings, one on the inside edge of the upper eyelid and one on the inside edge of the lower eyelid, near the nose. Each of these openings is called a lacrimal punctum. Together, these lacrimal puncta collect tears from the eye that are then conveyed through lacrimal ducts to a reservoir for tears called the lacrimal sac, also known as the dacrocyst or tear sac.

From the sac, tear fluid flows via a nasolacrimal duct to the inner nose. Each nasolacrimal duct is located underneath the skin and passes through the bones of the face into the nose. Chemicals in tears, such as defensins, lactoferrin, and lysozyme, help to prevent colonization by pathogens. In addition, mucins facilitate removal of microbes from the surface of the eye.

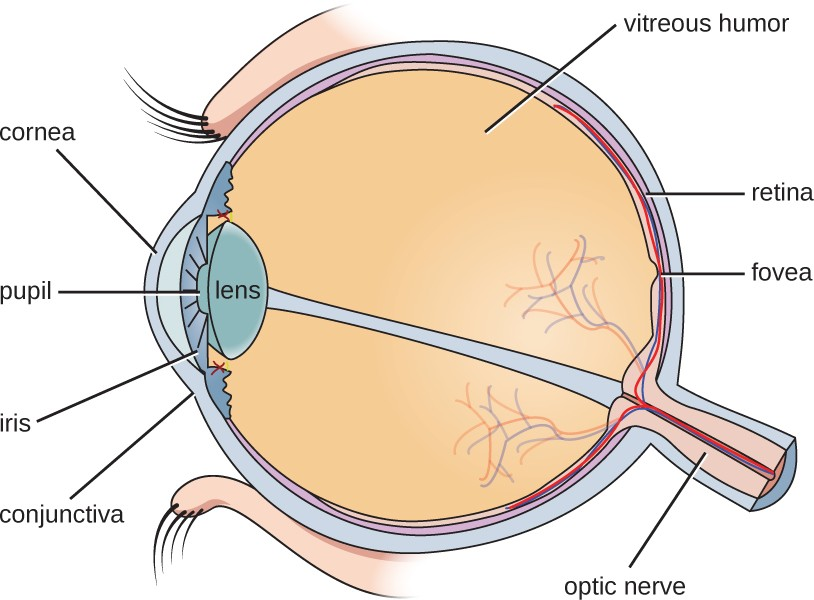

The surfaces of the eyeball and inner eyelid are mucous membranes called conjunctiva. The normal conjunctival microbiota has not been well characterized, but does exist. One small study (part of the Ocular Microbiome project) found twelve genera that were consistently present in the conjunctiva.[1] These microbes are thought to help defend the membranes against pathogens. However, it is still unclear which microbes may be transient and which may form a stable microbiota.[2]

Use of contact lenses can cause changes in the normal microbiota of the conjunctiva by introducing another surface into the natural anatomy of the eye. Research is currently underway to better understand how contact lenses may impact the normal microbiota and contribute to eye disease.

The watery material inside of the eyeball is called the vitreous humor. Unlike the conjunctiva, it is protected from contact with the environment and is almost always sterile, with no normal microbiota (Figure 16.5).

Infections of the Eye

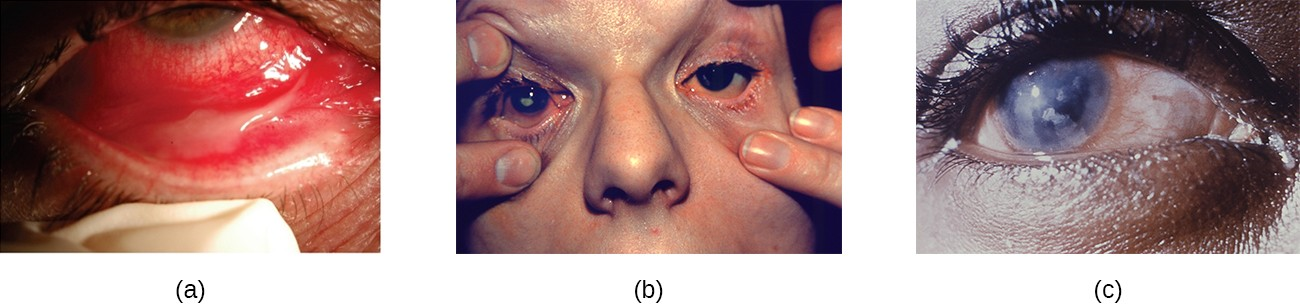

The conjunctiva is a frequent site of infection of the eye; like other mucous membranes, it is also a common portal of entry for pathogens. Inflammation of the conjunctiva is called conjunctivitis, although it is commonly known as pinkeye because of the pink appearance in the eye. Infections of deeper structures, beneath the cornea, are less common (Figure 16.6). Conjunctivitis occurs in multiple forms. It may be acute or chronic. Acute purulent conjunctivitis is associated with pus formation, while acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis is associated with bleeding in the conjunctiva. The term blepharitis refers to an inflammation of the eyelids, while keratitis refers to an inflammation of the cornea (Figure 16.6); keratoconjunctivitis is an inflammation of both the cornea and the conjunctiva, and dacryocystitis is an inflammation of the lacrimal sac that can often occur when a nasolacrimal duct is blocked.

Infections leading to conjunctivitis, blepharitis, keratoconjunctivitis, or dacryocystitis may be caused by bacteria or viruses, but allergens, pollutants, or chemicals can also irritate the eye and cause inflammation of various structures. Viral infection is a more likely cause of conjunctivitis in cases with symptoms such as fever and watery discharge that occurs with upper respiratory infection and itchy eyes.

![]()

- How does the lacrimal apparatus help to prevent eye infections?

- Abelson, M.B., Lane, K., and Slocum, C.. “The Secrets of Ocular Microbiomes.” Review of Ophthalmology June 8, 2015. http://www.reviewofophthalmology.com/content/t/ocular_disease/c/55178. Accessed Sept 14, 2016. ↵

- Shaikh-Lesko, R. “Visualizing the Ocular Microbiome.” The Scientist May 12, 2014. http://www.the-scientist.com/?articles.view/articleNo/39945/title/Visualizing-the-Ocular-Microbiome. Accessed Sept 14, 2016. ↵