15.1 Hypersensitivities

Learning Objectives

- Identify and compare the distinguishing characteristics, mechanisms, and major examples of type I, II, III, and IV hypersensitivities

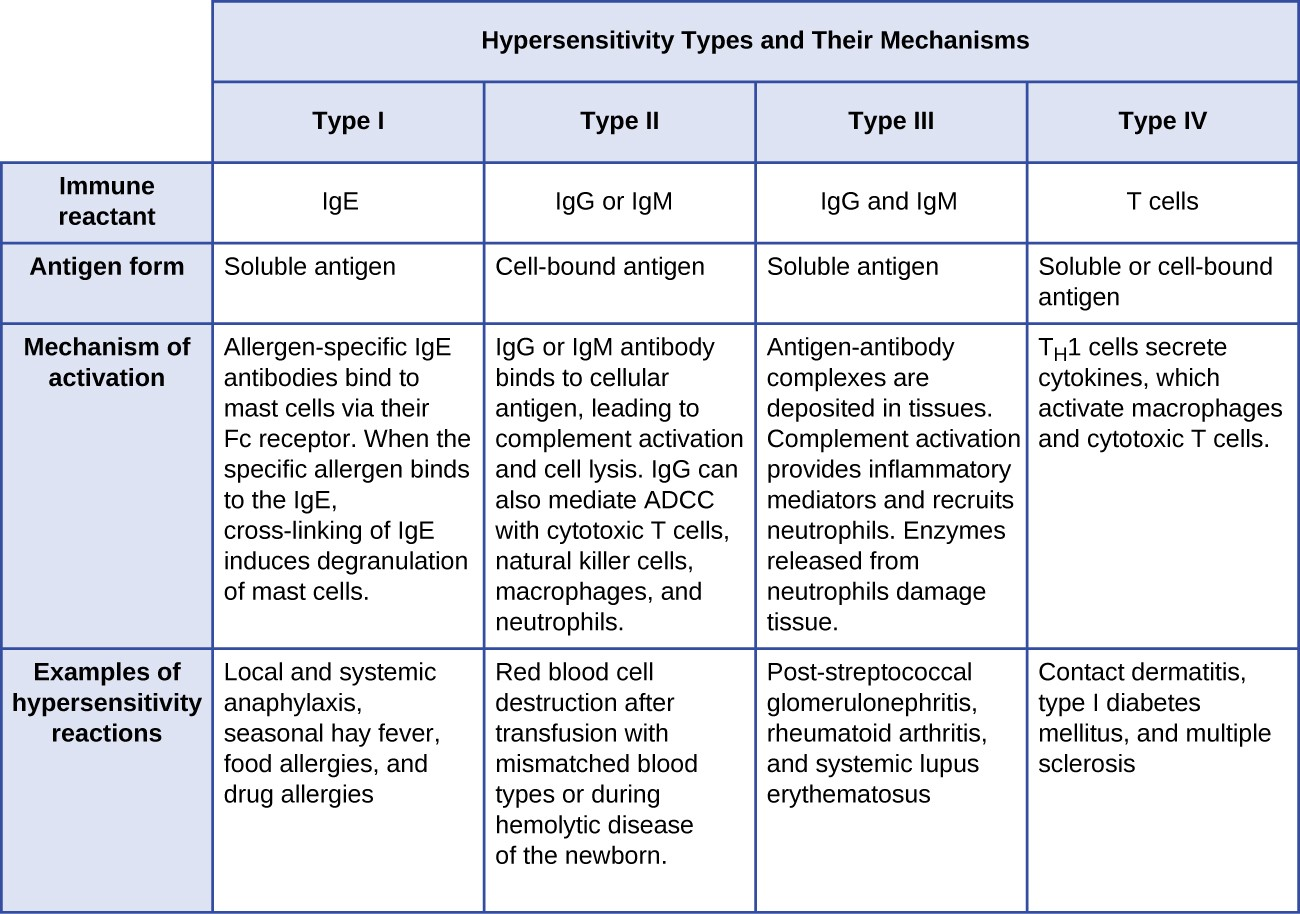

In Adaptive Specific Host Defenses, we discussed the mechanisms by which adaptive immune defenses, both humoral and cellular, protect us from infectious diseases. However, these same protective immune defenses can also be responsible for undesirable reactions called hypersensitivity reactions. Hypersensitivity reactions are classified by their immune mechanism.

- Type I hypersensitivity reactions involve immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibody against soluble antigen, triggering mast cell degranulation.

- Type II hypersensitivity reactions involve IgG and IgM antibodies directed against cellular antigens, leading to cell damage mediated by other immune system effectors.

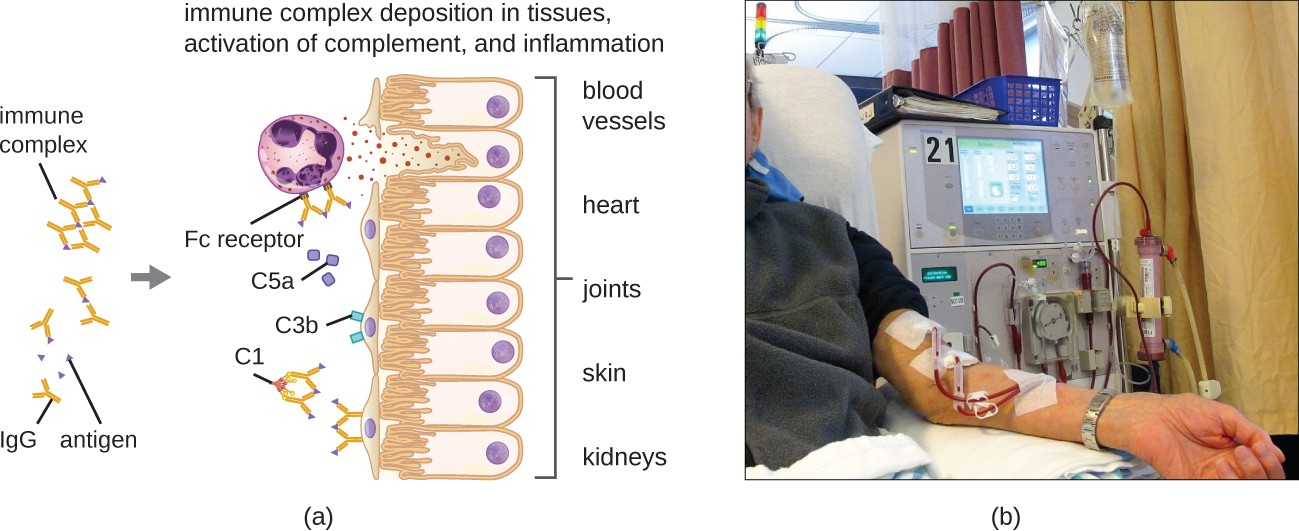

- Type III hypersensitivity reactions involve the interactions of IgG, IgM, and, occasionally, IgA[1] antibodies with antigen to form immune complexes. Accumulation of immune complexes in tissue leads to tissue damage mediated by other immune system effectors.

- Type IV hypersensitivity reactions are T-cell–mediated reactions that can involve tissue damage mediated by activated macrophages and cytotoxic T cells.

Type I Hypersensitivities

When a presensitized individual is exposed to an allergen, it can lead to a rapid immune response that occurs almost immediately. Such a response is called an allergy and is classified as a type I hypersensitivity. Allergens may be seemingly harmless substances such as animal dander, molds, or pollen. Allergens may also be substances considered innately more hazardous, such as insect venom or therapeutic drugs. Food intolerances can also yield allergic reactions as individuals become sensitized to foods such as peanuts or shellfish (Figure 15.2). Regardless of the allergen, the first exposure activates a primary IgE antibody response that sensitizes an individual to type I hypersensitivity reaction upon subsequent exposure.

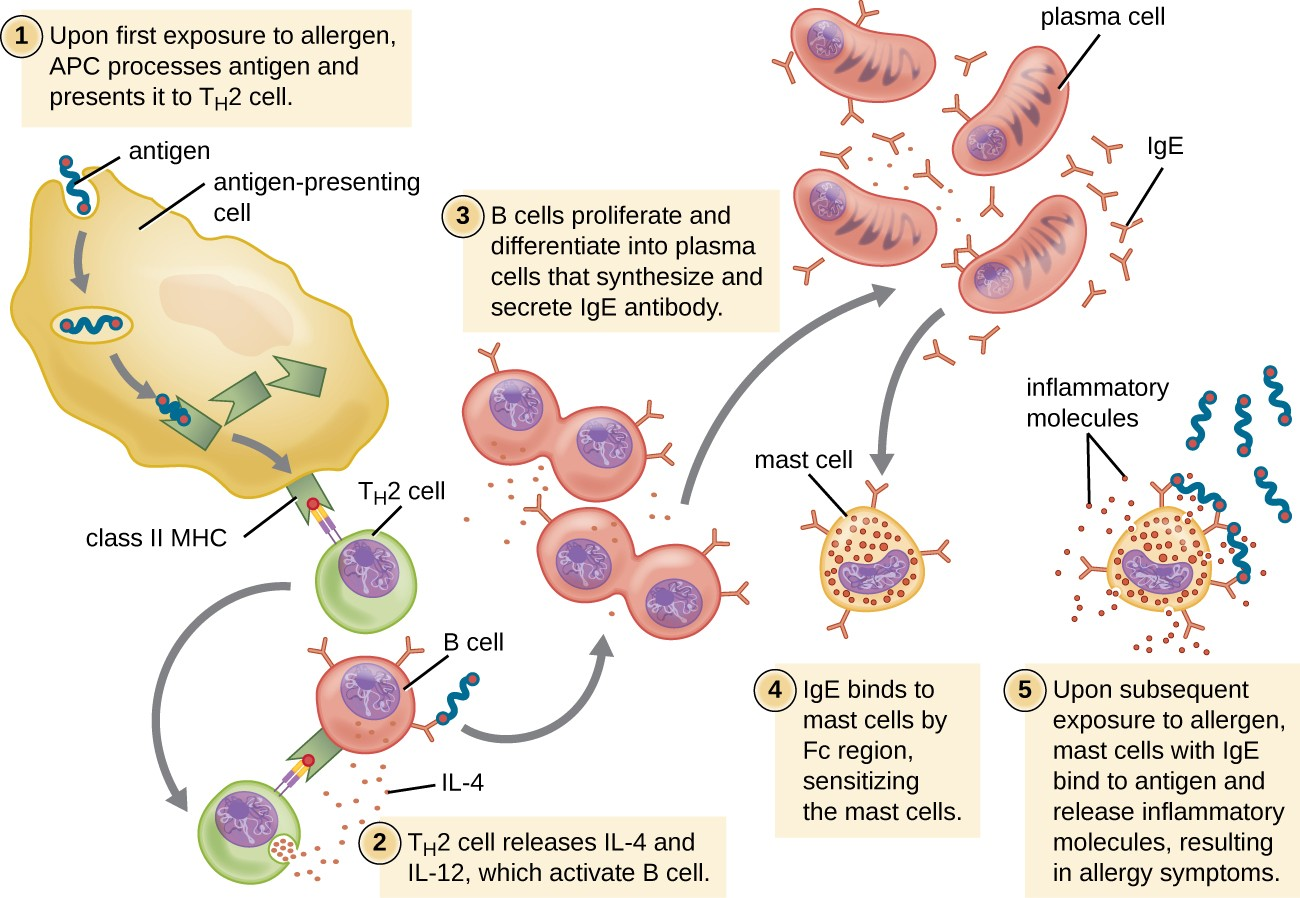

For susceptible individuals, a first exposure to an allergen activates a strong TH2 cell response (Figure 15.3). Cytokines interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-13 from the TH2 cells activate B cells specific to the same allergen, resulting in clonal proliferation, differentiation into plasma cells, and antibody-class switch from production of IgM to production of IgE. The fragment crystallizable (Fc) regions of the IgE antibodies bind to specific receptors on the surface of mast cells throughout the body. It is estimated that each mast cell can bind up to 500,000 IgE molecules, with each IgE molecule having two allergen-specific fragment antigen-binding (Fab) sites available for binding allergen on subsequent exposures. By the time this occurs, the allergen is often no longer present and there is no allergic reaction, but the mast cells are primed for a subsequent exposure and the individual is sensitized to the allergen.

On subsequent exposure, allergens bind to multiple IgE molecules on mast cells, cross-linking the IgE molecules. Within minutes, this cross-linking of IgE activates the mast cells and triggers degranulation, a reaction in which the contents of the granules in the mast cell are released into the extracellular environment. Preformed components that are released from granules include histamine, serotonin, and bradykinin (Table 15.1). The activated mast cells also release newly formed lipid mediators (leukotrienes and prostaglandins from membrane arachadonic acid metabolism) and cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (Table 15.2).

The chemical mediators released by mast cells collectively cause the inflammation and signs and symptoms associated with type I hypersensitivity reactions. Histamine stimulates mucus secretion in nasal passages and tear formation from lacrimal glands, promoting the runny nose and watery eyes of allergies. Interaction of histamine with nerve endings causes itching and sneezing. The vasodilation caused by several of the mediators can result in hives, headaches, angioedema (swelling that often affects the lips, throat, and tongue), and hypotension (low blood pressure). Bronchiole constriction caused by some of the chemical mediators leads to wheezing, dyspnea (difficulty breathing), coughing, and, in more severe cases, cyanosis (bluish color to the skin or mucous membranes). Vomiting can result from stimulation of the vomiting center in the cerebellum by histamine and serotonin. Histamine can also cause relaxation of intestinal smooth muscles and diarrhea.

|

Granule Component |

Activity |

|---|---|

|

Heparin |

Stimulates the generation of bradykinin, which causes increased vascular permeability, vasodilation, bronchiole constriction, and increased mucus secretion |

|

Histamine |

Causes smooth-muscle contraction, increases vascular permeability, increases mucus and tear formation |

|

Serotonin |

Increases vascular permeability, causes vasodilation and smooth-muscle contraction |

|

Chemical Mediator |

Activity |

|---|---|

|

Leukotriene |

Causes smooth-muscle contraction and mucus secretion, increases vascular permeability |

|

Prostaglandin |

Causes smooth-muscle contraction and vasodilation |

|

TNF-α (cytokine) |

Causes inflammation and stimulates cytokine production by other cell types |

Type I hypersensitivity reactions can be either localized or systemic. Localized type I hypersensitivity reactions include hay fever rhinitis, hives, and asthma (Table 15.3). Systemic type I hypersensitivity reactions are referred to as anaphylaxis or anaphylactic shock. Although anaphylaxis shares many symptoms common with the localized type I hypersensitivity reactions, the swelling of the tongue and trachea, blockage of airways, dangerous drop in blood pressure, and development of shock can make anaphylaxis especially severe and life-threatening. In fact, death can occur within minutes of onset of signs and symptoms.

Late-phase reactions in type I hypersensitivities may develop 4–12 hours after the early phase and are mediated by eosinophils, neutrophils, and lymphocytes that have been recruited by chemotactic factors released from mast cells. Activation of these recruited cells leads to the release of more chemical mediators that cause tissue damage and late- phase symptoms of swelling and redness of the skin, coughing, wheezing, and nasal discharge.

Individuals who possess genes for maladaptive traits, such as intense type I hypersensitivity reactions to otherwise harmless components of the environment, would be expected to suffer reduced reproductive success. With this kind of evolutionary selective pressure, such traits would not be expected to persist in a population. This suggests that type I hypersensitivities may have an adaptive function. There is evidence that the IgE produced during type I hypersensitivity reactions is actually meant to counter helminth infections.[2] Helminths are one of few organisms that possess proteins that are targeted by IgE. In addition, there is evidence that helminth infections at a young age reduce the likelihood of type I hypersensitivities to innocuous substances later in life. Thus it may be that allergies are an unfortunate consequence of strong selection in the mammalian lineage or earlier for a defense against parasitic worms.

|

Common Name |

Cause |

Signs and Symptoms |

|---|---|---|

|

Allergy-induced asthma |

Inhalation of allergens |

Constriction of bronchi, labored breathing, coughing, chills, body aches |

|

Anaphylaxis |

Systemic reaction to allergens |

Hives, itching, swelling of tongue and throat, nausea, vomiting, low blood pressure, shock |

|

Hay fever |

Inhalation of mold or pollen |

Runny nose, watery eyes, sneezing |

|

Hives (urticaria) |

Food or drug allergens, insect stings |

Raised, bumpy skin rash with itching; bumps may converge into large raised areas |

![]()

- What are the cells that cause a type I hypersensitivity reaction?

- Describe the differences between immediate and late-phase type I hypersensitivity reactions.

- List the signs and symptoms of anaphylaxis.

Micro Connections

The Hygiene Hypothesis

In most modern societies, good hygiene is associated with regular bathing, and good health with cleanliness. But some recent studies suggest that the association between health and clean living may be a faulty one. Some go so far as to suggest that children should be encouraged to play in the dirt—or even eat dirt[3]—for the benefit of their health. This recommendation is based on the so-called hygiene hypothesis, which proposes that childhood exposure to antigens from a diverse range of microbes leads to a better-functioning immune system later in life.

The hygiene hypothesis was first suggested in 1989 by David Strachan[4], who observed an inverse relationship between the number of older children in a family and the incidence of hay fever. Although hay fever in children had increased dramatically during the mid-20th century, incidence was significantly lower in families with more children. Strachan proposed that the lower incidence of allergies in large families could be linked to infections acquired from older siblings, suggesting that these infections made children less susceptible to allergies. Strachan also argued that trends toward smaller families and a greater emphasis on cleanliness in the 20th century had decreased exposure to pathogens and thus led to higher overall rates of allergies, asthma, and other immune disorders.

Other researchers have observed an inverse relationship between the incidence of immune disorders and infectious diseases that are now rare in industrialized countries but still common in less industrialized countries.[5] In developed nations, children under the age of 5 years are not exposed to many of the microbes, molecules, and antigens they almost certainly would have encountered a century ago. The lack of early challenges to the immune system by organisms with which humans and their ancestors evolved may result in failures in immune system functioning later in life.

Type II (Cytotoxic) Hypersensitivities

Immune reactions categorized as type II hypersensitivities, or cytotoxic hypersensitivities, are mediated by IgG and IgM antibodies binding to cell-surface antigens or matrix-associated antigens on basement membranes. These antibodies can either activate complement, resulting in an inflammatory response and lysis of the targeted cells, or they can be involved in antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) with cytotoxic T cells.

In some cases, the antigen may be a self-antigen, in which case the reaction would also be described as an autoimmune disease. (Autoimmune diseases are described in Autoimmune Disorders). In other cases, antibodies may bind to naturally occurring, but exogenous, cell-surface molecules such as antigens associated with blood typing found on red blood cells (RBCs). This leads to the coating of the RBCs by antibodies, activation of the complement cascade, and complement-mediated lysis of RBCs, as well as opsonization of RBCs for phagocytosis. Two examples of type II hypersensitivity reactions involving RBCs are hemolytic transfusion reaction (HTR) and hemolytic disease of the newborn (HDN). These type II hypersensitivity reactions, which will be discussed in greater detail, are summarized in Table 15.4.

Immunohematology is the study of blood and blood-forming tissue in relation to the immune response. Antibody- initiated responses against blood cells are type II hypersensitivities, thus falling into the field of immunohematology. For students first learning about immunohematology, understanding the immunological mechanisms involved is made even more challenging by the complex nomenclature system used to identify different blood-group antigens, often called blood types. The first blood-group antigens either used alphabetical names or were named for the first person known to produce antibodies to the red blood cell antigen (e.g., Kell, Duffy, or Diego). However, in 1980, the International Society of Blood Transfusion (ISBT) Working Party on Terminology created a standard for blood-group terminology in an attempt to more consistently identify newly discovered blood group antigens. New antigens are now given a number and assigned to a blood-group system, collection, or series. However, even with this effort, blood-group nomenclature is still inconsistent.

|

Common Name |

Cause |

Signs and Symptoms |

|---|---|---|

|

Hemolytic disease of the newborn (HDN) |

IgG from mother crosses the placenta, targeting the fetus’ RBCs for destruction |

Anemia, edema, enlarged liver or spleen, hydrops (fluid in body cavity), leading to death of newborn in severe cases |

|

Hemolytic transfusion reactions (HTR) |

IgG and IgM bind to antigens on transfused RBCs, targeting donor RBCs for destruction |

Fever, jaundice, hypotension, disseminated intravascular coagulation, possibly leading to kidney failure and death |

ABO Blood Group Incompatibility

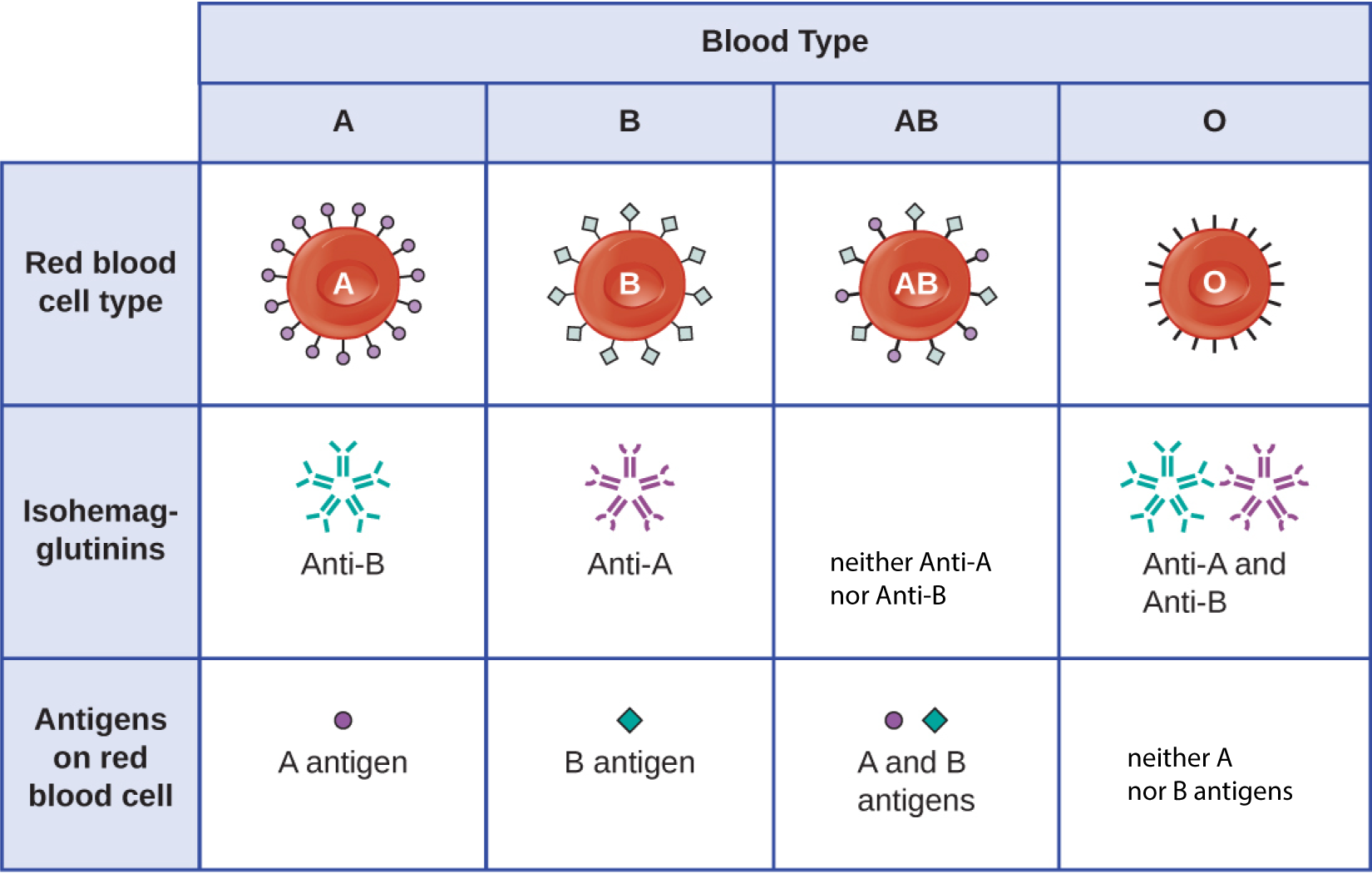

The recognition that individuals have different blood types was first described by Karl Landsteiner (1868–1943) in the early 1900s, based on his observation that serum from one person could cause a clumping of RBCs from another. These studies led Landsteiner to the identification of four distinct blood types. Subsequent research by other scientists determined that the four blood types were based on the presence or absence of surface carbohydrates “A” and “B,” and this provided the foundation for the ABO blood group system that is still in use today (Figure 15.4). The functions of these antigens are unknown, but some have been associated with normal biochemical functions of the cell. Furthermore, ABO blood types are inherited as alleles (one from each parent), and they display patterns of dominant and codominant inheritance. The alleles for A and B blood types are codominant to each other, and both are dominant over blood type O. Therefore, individuals with genotypes of AA or AO have type A blood and express the A carbohydrate antigen on the surface of their RBCs. People with genotypes of BB or BO have type B blood and express the B carbohydrate antigen on the surface of their RBCs. Those with a genotype of AB have type AB blood and express both A and B carbohydrate antigens on the surface of their RBCs. Finally, individuals with a genotype of OO have type O blood and lack A and B carbohydrate on the surface of their RBCs.

It is important to note that the RBCs of all four ABO blood types share a common protein receptor molecule, and it is the addition of specific carbohydrates to the protein receptors that determines A, B, and AB blood types. The genes that are inherited for the A, B, and AB blood types encode enzymes that add the carbohydrate component to the protein receptor. Individuals with O blood type still have the protein receptor but lack the enzymes that would add carbohydrates that would make their red blood cell type A, B, or AB.

IgM antibodies in plasma that cross-react with blood group antigens not present on an individual’s own RBCs are called isohemagglutinins (Figure 15.4). Isohemagglutinins are produced within the first few weeks after birth and persist throughout life. These antibodies are produced in response to exposure to environmental antigens from food and microorganisms. A person with type A blood has A antigens on the surface of their RBCs and will produce anti-B antibodies to environmental antigens that resemble the carbohydrate component of B antigens. A person with type B blood has B antigens on the surface of their RBCs and will produce anti-A antibodies to environmental antigens that are similar to the carbohydrate component of A antigens. People with blood type O lack both A and B antigens on their RBCs and, therefore, produce both anti-A and anti-B antibodies. Conversely, people with AB blood type have both A and B antigens on their RBCs and, therefore, lack anti-A and anti-B antibodies.

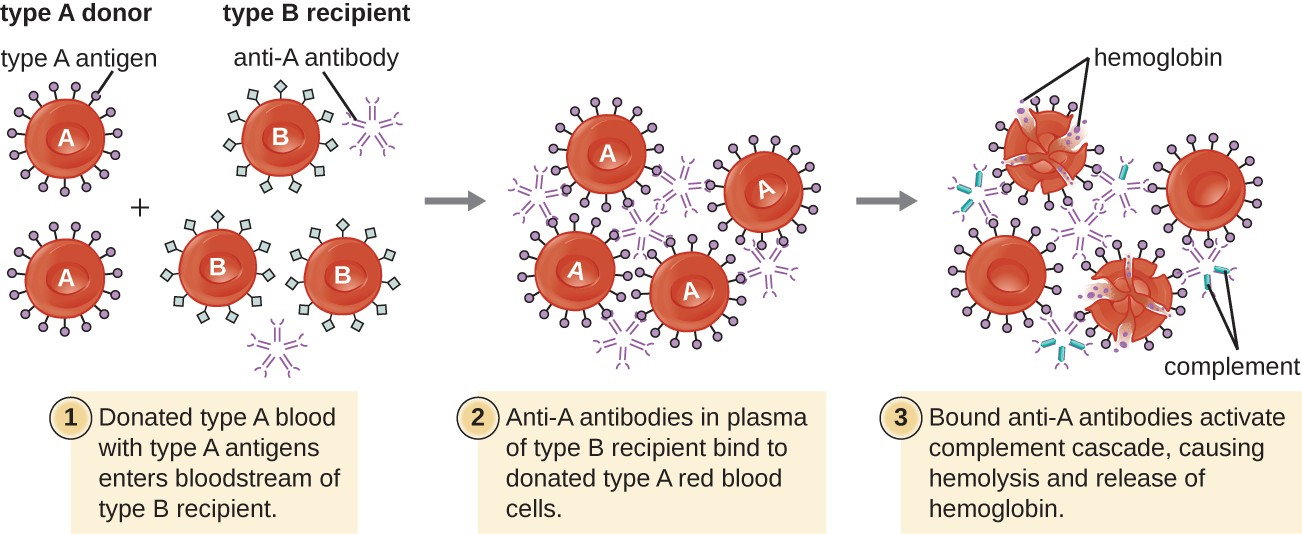

A patient may require a blood transfusion because they lack sufficient RBCs (anemia) or because they have experienced significant loss of blood volume through trauma or disease. Although the blood transfusion is given to help the patient, it is essential that the patient receive a transfusion with matching ABO blood type. A transfusion with an incompatible ABO blood type may lead to a strong, potentially lethal type II hypersensitivity cytotoxic response called hemolytic transfusion reaction (HTR) (Figure 15.5).

For instance, if a person with type B blood receives a transfusion of type A blood, their anti-A antibodies will bind to and agglutinate the transfused RBCs. In addition, activation of the classical complement cascade will lead to a strong inflammatory response, and the complement membrane attack complex (MAC) will mediate massive hemolysis of the transfused RBCs. The debris from damaged and destroyed RBCs can occlude blood vessels in the alveoli of the lungs and the glomeruli of the kidneys. Within 1 to 24 hours of an incompatible transfusion, the patient experiences fever, chills, pruritus (itching), urticaria (hives), dyspnea, hemoglobinuria (hemoglobin in the urine), and hypotension (low blood pressure). In the most serious reactions, dangerously low blood pressure can lead to shock, multi-organ failure, and death of the patient.

Hospitals, medical centers, and associated clinical laboratories typically use hemovigilance systems to minimize the risk of HTRs due to clerical error. Hemovigilance systems are procedures that track transfusion information from the donor source and blood products obtained to the follow-up of recipient patients. Hemovigilance systems used in many countries identify HTRs and their outcomes through mandatory reporting (e.g., to the Food and Drug Administration in the United States), and this information is valuable to help prevent such occurrences in the future. For example, if an HTR is found to be the result of laboratory or clerical error, additional blood products collected from the donor at that time can be located and labeled correctly to avoid additional HTRs. As a result of these measures, HTR-associated deaths in the United States occur in about one per 2 million transfused units.[6]

Rh Factors

Many different types of erythrocyte antigens have been discovered since the description of the ABO red cell antigens. The second most frequently described RBC antigens are Rh factors, named after the rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta) factors identified by Karl Landsteiner and Alexander Weiner in 1940. The Rh system of RBC antigens is the most complex and immunogenic blood group system, with more than 50 specificities identified to date. Of all the Rh antigens, the one designated Rho (Weiner) or D (Fisher-Race) is the most immunogenic. Cells are classified as Rh positive (Rh+) if the Rho/D antigen is present or as Rh negative (Rh−) if the Rho/D antigen is absent. In contrast to the carbohydrate molecules that distinguish the ABO blood groups and are the targets of IgM isohemagglutinins in HTRs, the Rh factor antigens are proteins. As discussed in B Lymphocytes and Humoral Immunity, protein antigens activate B cells and antibody production through a T-cell–dependent mechanism, and the TH2 cells stimulate class switching from IgM to other antibody classes. In the case of Rh factor antigens, TH2 cells stimulate class switching to IgG, and this has important implications for the mechanism of HDN.

Like ABO incompatibilities, blood transfusions from a donor with the wrong Rh factor antigens can cause a type II hypersensitivity HTR. However, in contrast to the IgM isohemagglutinins produced early in life through exposure to environmental antigens, production of anti-Rh factor antibodies requires the exposure of an individual with Rh− blood to Rh+ positive RBCs and activation of a primary antibody response. Although this primary antibody response can cause an HTR in the transfusion patient, the hemolytic reaction would be delayed up to 2 weeks during the extended lag period of a primary antibody response. However, if the patient receives a subsequent transfusion with Rh+ RBCs, a more rapid HTR would occur with anti-Rh factor antibody already present in the blood. Furthermore, the rapid secondary antibody response would provide even more anti-Rh factor antibodies for the HTR.

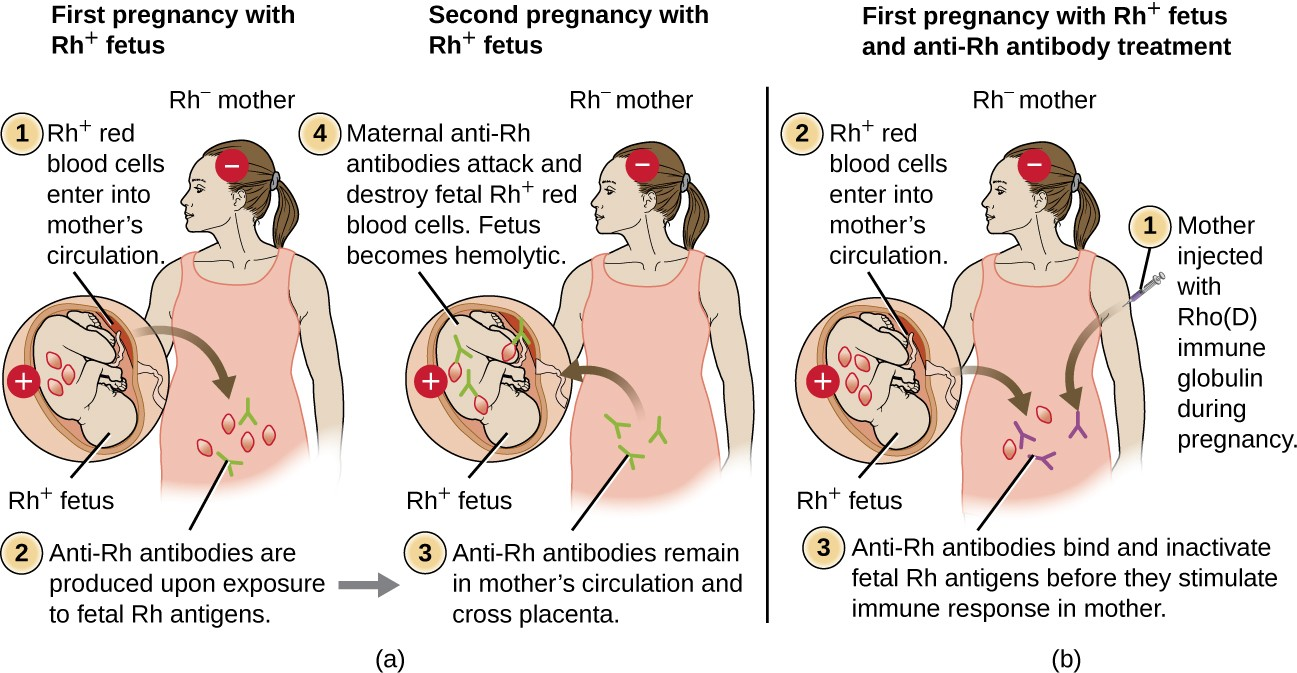

Rh factor incompatibility between mother and fetus can also cause a type II hypersensitivity hemolytic reaction, referred to as hemolytic disease of the newborn (HDN) (Figure 15.6). If an Rh− woman carries an Rh+ baby to term, the mother’s immune system can be exposed to Rh+ fetal red blood cells. This exposure will usually occur during the last trimester of pregnancy and during the delivery process. If this exposure occurs, the Rh+ fetal RBCs will activate a primary adaptive immune response in the mother, and anti-Rh factor IgG antibodies will be produced. IgG antibodies are the only class of antibody that can cross the placenta from mother to fetus; however, in most cases, the first Rh+ baby is unaffected by these antibodies because the first exposure typically occurs late enough in the pregnancy that the mother does not have time to mount a sufficient primary antibody response before the baby is born.

If a subsequent pregnancy with an Rh+ fetus occurs, however, the mother’s second exposure to the Rh factor antigens causes a strong secondary antibody response that produces larger quantities of anti-Rh factor IgG. These antibodies can cross the placenta from mother to fetus and cause HDN, a potentially lethal condition for the baby (Figure 15.6).

Prior to the development of techniques for diagnosis and prevention, Rh factor incompatibility was the most common cause of HDN, resulting in thousands of infant deaths each year worldwide.[7] For this reason, the Rh factors of prospective parents are regularly screened, and treatments have been developed to prevent HDN caused by Rh incompatibility. To prevent Rh factor-mediated HDN, human Rho(D) immune globulin (e.g., RhoGAM) is injected intravenously or intramuscularly into the mother during the 28th week of pregnancy and within 72 hours after delivery. Additional doses may be administered after events that may result in transplacental hemorrhage (e.g., umbilical blood sampling, chorionic villus sampling, abdominal trauma, amniocentesis). This treatment is initiated during the first pregnancy with an Rh+ fetus. The anti-Rh antibodies in Rho(D) immune globulin will bind to the Rh factor of any fetal RBCs that gain access to the mother’s bloodstream, preventing these Rh+ cells from activating the mother’s primary antibody response. Without a primary anti-Rh factor antibody response, the next pregnancy with an Rh+ will have minimal risk of HDN. However, the mother will need to be retreated with Rho(D) immune globulin during that pregnancy to prevent a primary anti-Rh antibody response that could threaten subsequent pregnancies.

Link to Learning

Use this interactive Blood Typing Game (https://openstax.org/l/22actbloodtyping) to reinforce your knowledge of blood typing.

![]()

- What happens to cells that possess incompatible antigens in a type II hypersensitivity reaction?

- Describe hemolytic disease of the newborn and explain how it can be prevented.

Type III Hypersensitivities

Type III hypersensitivities are immune-complex reactions that were first characterized by Nicolas Maurice Arthus (1862–1945) in 1903. To produce antibodies for experimental procedures, Arthus immunized rabbits by injecting them with serum from horses. However, while immunizing rabbits repeatedly with horse serum, Arthus noticed a previously unreported and unexpected localized subcutaneous hemorrhage with edema at the site of injection. This reaction developed within 3 to10 hours after injection. This localized reaction to non-self serum proteins was called an Arthus reaction. An Arthus reaction occurs when soluble antigens bind with IgG in a ratio that results in the accumulation of antigen-antibody aggregates called immune complexes.

A unique characteristic of type III hypersensitivity is antibody excess (primarily IgG), coupled with a relatively low concentration of antigen, resulting in the formation of small immune complexes that deposit on the surface of the epithelial cells lining the inner lumen of small blood vessels or on the surfaces of tissues (Figure 15.7). This immune complex accumulation leads to a cascade of inflammatory events that include the following:

- IgG binding to antibody receptors on localized mast cells, resulting in mast-cell degranulation

- Complement activation with production of pro-inflammatory C3a and C5a (see Chemical Defenses)

- Increased blood-vessel permeability with chemotactic recruitment of neutrophils and macrophages

Because these immune complexes are not an optimal size and are deposited on cell surfaces, they cannot be phagocytosed in the usual way by neutrophils and macrophages, which, in turn, are often described as “frustrated.” Although phagocytosis does not occur, neutrophil degranulation results in the release of lysosomal enzymes that causeextracellular destruction of the immune complex, damaging localized cells in the process. Activation of coagulation pathways also occurs, resulting in thrombi (blood clots) that occlude blood vessels and cause ischemia that can lead to vascular necrosis and localized hemorrhage.

Systemic type III hypersensitivity (serum sickness) occurs when immune complexes deposit in various body sites, resulting in a more generalized systemic inflammatory response. These immune complexes involve non-self proteins such as antibodies produced in animals for artificial passive immunity (see Vaccines), certain drugs, or microbial antigens that are continuously released over time during chronic infections (e.g., subacute bacterial endocarditis, chronic viral hepatitis). The mechanisms of serum sickness are similar to those described in localized type III hypersensitivity but involve widespread activation of mast cells, complement, neutrophils, and macrophages, which causes tissue destruction in areas such as the kidneys, joints, and blood vessels. As a result of tissue destruction, symptoms of serum sickness include chills, fever, rash, vasculitis, and arthritis. Development of glomerulonephritis or hepatitis is also possible.

Autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and rheumatoid arthritis can also involve damaging type III hypersensitivity reactions when auto-antibodies form immune complexes with self antigens. These conditions are discussed in Autoimmune Disorders.

![]()

- Why is antibody excess important in type III hypersensitivity?

- Describe the differences between the Arthus reaction and serum sickness.

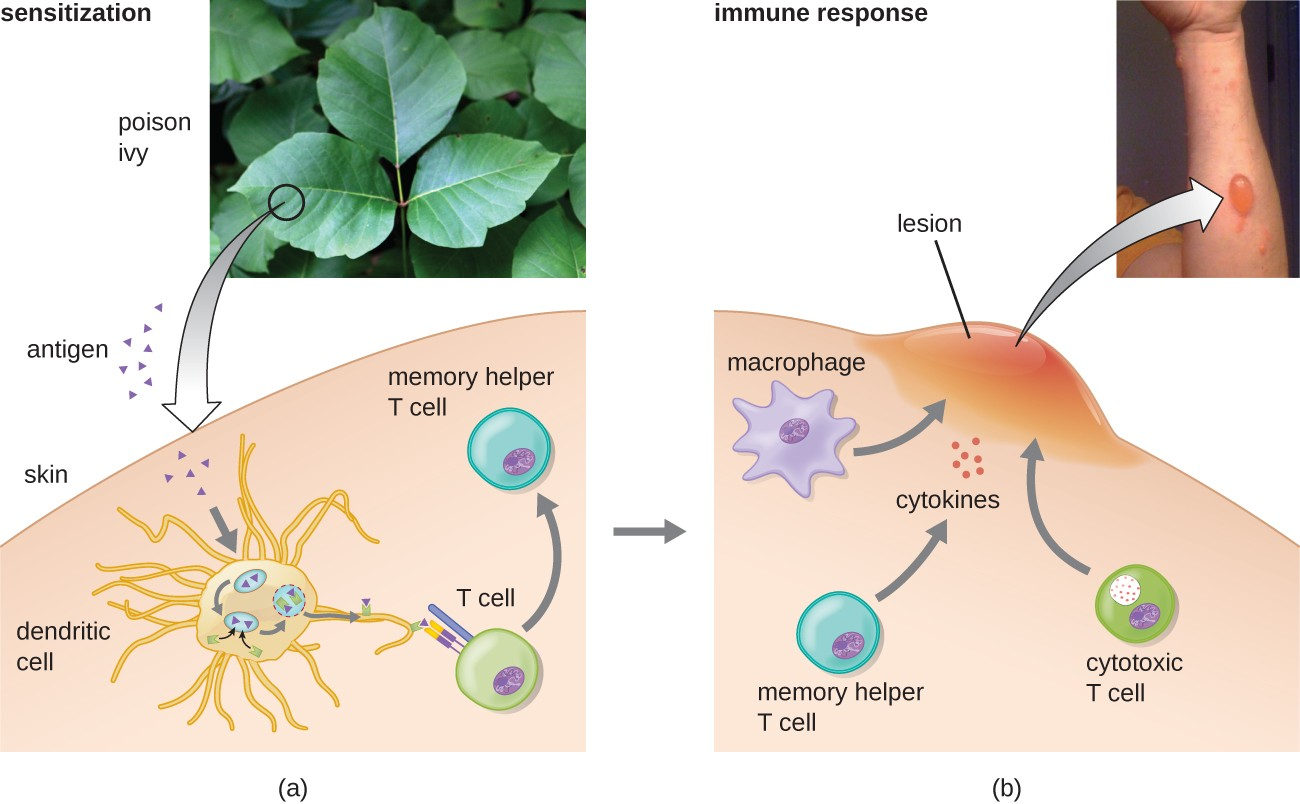

Type IV Hypersensitivities

Type IV hypersensitivities are not mediated by antibodies like the other three types of hypersensitivities. Rather, type IV hypersensitivities are regulated by T cells and involve the action of effector cells. These types of hypersensitivities can be organized into three subcategories based on T-cell subtype, type of antigen, and the resulting effector mechanism (Table 15.5).

In the first type IV subcategory, CD4 TH1-mediated reactions are described as delayed-type hypersensitivities (DTH). The sensitization step involves the introduction of antigen into the skin and phagocytosis by local antigen presenting cells (APCs). The APCs activate helper T cells, stimulating clonal proliferation and differentiation into memory TH1 cells. Upon subsequent exposure to the antigen, these sensitized memory TH1 cells release cytokines that activate macrophages, and activated macrophages are responsible for much of the tissue damage. Examples of this TH1-mediated hypersensitivity are observed in tuberculin the Mantoux skin test and contact dermatitis, such as occurs in latex allergy reactions.

In the second type IV subcategory, CD4 TH2-mediated reactions result in chronic asthma or chronic allergic rhinitis. In these cases, the soluble antigen is first inhaled, resulting in eosinophil recruitment and activation with the release of cytokines and inflammatory mediators.

In the third type IV subcategory, CD8 cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL)-mediated reactions are associated with tissue transplant rejection and contact dermatitis (Figure 15.8). For this form of cell-mediated hypersensitivity, APCs process and present the antigen with MHC I to naïve CD8 T cells. When these naïve CD8 T cells are activated, they proliferate and differentiate into CTLs. Activated TH1 cells can also enhance the activation of the CTLs. The activated CTLs then target and induce granzyme-mediated apoptosis in cells presenting the same antigen with MHC I. These target cells could be “self” cells that have absorbed the foreign antigen (such as with contact dermatitis due to poison ivy), or they could be transplanted tissue cells displaying foreign antigen from the donor.

|

Subcategory |

Antigen |

Effector Mechanism |

Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

Soluble antigen |

Activated macrophages damage tissue and promote inflammatory response |

Contact dermatitis (e.g., exposure to latex) and delayed-type hypersensitivity (e.g., tuberculin reaction) |

|

2 |

Soluble antigen |

Eosinophil recruitment and activation release cytokines and pro-inflammatory chemicals |

Chronic asthma and chronic allergic rhinitis |

|

3 |

Cell- associated antigen |

CTL-mediated cytotoxicity |

Contact dermatitis (e.g., contact with poison ivy) and tissue-transplant rejection |

![]()

- Describe the three subtypes of type IV hypersensitivity.

- Explain how T cells contribute to tissue damage in type IV hypersensitivity.

Micro Connections

Using Delayed Hypersensitivity to Test for TB

Austrian pediatrician Clemans von Pirquet (1874–1929) first described allergy mechanisms, including type III serum sickness.[8] His interest led to the development of a test for tuberculosis (TB), using the tuberculin antigen, based on earlier work identifying the TB pathogen performed by Robert Koch. Pirquet’s method involved scarification, which results in simultaneous multiple punctures, using a device with an array of needles to break the skin numerous times in a small area. The device Pirquet used was similar to the tine test device with four needles seen in Figure 15.9.

The tips of all the needles in the array are coated with tuberculin, a protein extract of TB bacteria, effectively introducing the tuberculin into the skin. One to 3 days later, the area can be examined for a delayed hypersensitivity reaction, signs of which include swelling and redness.

As you can imagine, scarification was not a pleasant experience,[9] and the numerous skin punctures put the patient at risk of developing bacterial infection of the skin. Mantoux modified Pirquet’s test to use a single subcutaneous injection of purified tuberculin material. A positive test, which is indicated by a delayed localized swelling at the injection site, does not necessarily mean that the patient is currently infected with active TB. Because type IV (delayed-type) hypersensitivity is mediated by reactivation of memory T cells, such cells may have been created recently (due to an active current infection) or years prior (if a patient had TB and had spontaneously cleared it, or if it had gone into latency). However, the test can be used to confirm infection in cases in which symptoms in the patient or findings on a radiograph suggest its presence.

- D.S. Strayer et al (eds). Rubin’s Pathology: Clinicopathologic Foundations of Medicine. 7th ed. 2Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 2014. ↵

- C.M. Fitzsimmons et al. “Helminth Allergens, Parasite-Specific IgE, and Its Protective Role in Human Immunity.” Frontier in Immunology 5 (2015):47. ↵

- S.T. Weiss. “Eat Dirt—The Hygiene Hypothesis and Allergic Diseases.” New England Journal of Medicine 347 no. 12 (2002):930–931. ↵

- D.P. Strachan “Hay Fever, Hygiene, and Household Size.” British Medical Journal 299 no. 6710 (1989):1259. ↵

- H. Okada et al. “The ‘Hygiene Hypothesis’ for Autoimmune and Allergic Diseases: An Update.” Clinical & Experimental Immunology 160 no. 1 (2010):1–9. ↵

- E.C. Vamvakas, M.A. Blajchman. “Transfusion-Related Mortality: The Ongoing Risks of Allogeneic Blood Transfusion and the Available Strategies for Their Prevention.” Blood 113 no. 15 (2009):3406–3417. ↵

- G. Reali. “Forty Years of Anti-D Immunoprophylaxis.” Blood Transfusion 5 no. 1 (2007):3–6. ↵

- B. Huber “100 Jahre Allergie: Clemens von Pirquet–sein Allergiebegriff und das ihm zugrunde liegende Krankheitsverständnis.” Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift 118 no. 19–20 (2006):573–579. ↵

- C.A. Stewart. “The Pirquet Test: Comparison of the Scarification and the Puncture Methods of Application.” Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 35 no. 3 (1928):388–391. ↵