10.1 Fundamentals of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy

Learning Objectives

- Contrast bacteriostatic versus bactericidal antibacterial activities

- Contrast broad-spectrum drugs versus narrow-spectrum drugs

- Explain the significance of superinfections

Several factors are important in choosing the most appropriate antimicrobial drug therapy, including bacteriostatic versus bactericidal mechanisms, spectrum of activity, dosage and route of administration, the potential for side effects, and the potential interactions between drugs. The following discussion will focus primarily on antibacterial drugs, but the concepts translate to other antimicrobial classes.

Bacteriostatic Versus Bactericidal

Antibacterial drugs can be either bacteriostatic or bactericidal in their interactions with target bacteria. Bacteriostatic drugs cause a reversible inhibition of growth, with bacterial growth restarting after elimination of the drug. By contrast, bactericidal drugs kill their target bacteria. The decision of whether to use a bacteriostatic or bactericidal drugs depends on the type of infection and the immune status of the patient. In a patient with strong immune defenses, bacteriostatic and bactericidal drugs can be effective in achieving clinical cure. However, when a patient is immunocompromised, a bactericidal drug is essential for the successful treatment of infections. Regardless of the immune status of the patient, life-threatening infections such as acute endocarditis require the use of a bactericidal drug.

Spectrum of Activity

The spectrum of activity of an antibacterial drug relates to diversity of targeted bacteria. A narrow-spectrum antimicrobial targets only specific subsets of bacterial pathogens. For example, some narrow-spectrum drugs only target gram-positive bacteria, whereas others target only gram-negative bacteria. If the pathogen causing an infection has been identified, it is best to use a narrow-spectrum antimicrobial and minimize collateral damage to the normal microbiota. A broad-spectrum antimicrobial targets a wide variety of bacterial pathogens, including both gram- positive and gram-negative species, and is frequently used as empiric therapy to cover a wide range of potential pathogens while waiting on the laboratory identification of the infecting pathogen. Broad-spectrum antimicrobials are also used for polymicrobic infections (mixed infection with multiple bacterial species), or as prophylactic prevention of infections with surgery/invasive procedures. Finally, broad-spectrum antimicrobials may be selected to treat an infection when a narrow-spectrum drug fails because of development of drug resistance by the target pathogen.

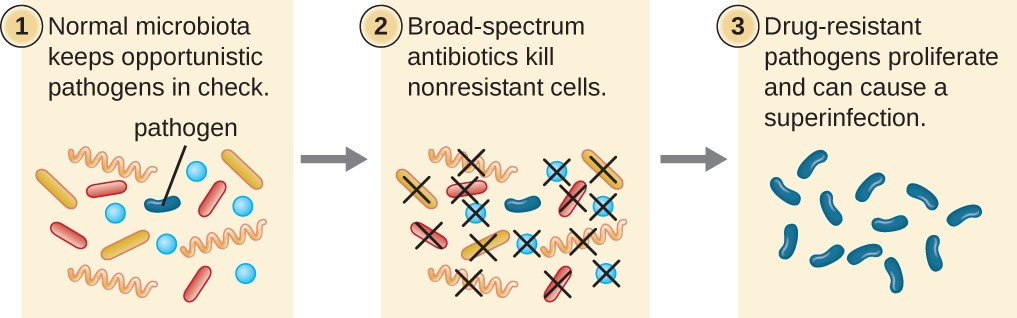

The risk associated with using broad-spectrum antimicrobials is that they will also target a broad spectrum of the normal microbiota, increasing the risk of a superinfection, a secondary infection in a patient having a preexisting infection. A superinfection develops when the antibacterial intended for the preexisting infection kills the protective microbiota, allowing another pathogen resistant to the antibacterial to proliferate and cause a secondary infection (Figure 10.2)

![]()

- What is a superinfection and how does one arise?