8.1 Whole Genome Methods and Pharmaceutical Applications of Genetic Engineering

Learning Objectives

- Explain the uses of genome-wide comparative analyses

- Summarize the advantages of genetically engineered pharmaceutical products

Advances in molecular biology have led to the creation of entirely new fields of science. Among these are fields that study aspects of whole genomes, collectively referred to as whole-genome methods. In this section, we’ll provide a brief overview of the whole-genome fields of genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics.

Genomics, Transcriptomics, and Proteomics

The study and comparison of entire genomes, including the complete set of genes and their nucleotide sequence and organization, is called genomics. This field has great potential for future medical advances through the study of the human genome as well as the genomes of infectious organisms. Analysis of microbial genomes has contributed to the development of new antibiotics, diagnostic tools, vaccines, medical treatments, and environmental cleanup techniques.

The field of transcriptomics is the science of the entire collection of mRNA molecules produced by cells. Scientists compare gene expression patterns between infected and uninfected host cells, gaining important information about the cellular responses to infectious disease. Additionally, transcriptomics can be used to monitor the gene expression of virulence factors in microorganisms, aiding scientists in better understanding pathogenic processes from this viewpoint.

When genomics and transcriptomics are applied to entire microbial communities, we use the terms metagenomics and metatranscriptomics, respectively. Metagenomics and metatranscriptomics allow researchers to study genes and gene expression from a collection of multiple species, many of which may not be easily cultured or cultured at all in the laboratory.

Another up-and-coming clinical application of genomics and transcriptomics is pharmacogenomics, also called toxicogenomics, which involves evaluating the effectiveness and safety of drugs on the basis of information from an individual’s genomic sequence. Genomic responses to drugs can be studied using experimental animals (such as laboratory rats or mice) or live cells in the laboratory before embarking on studies with humans. Changes in gene expression in the presence of a drug can sometimes be an early indicator of the potential for toxic effects. Personal genome sequence information may someday be used to prescribe medications that will be most effective and least toxic on the basis of the individual patient’s genotype.

The study of proteomics is an extension of genomics that allows scientists to study the entire complement of proteins in an organism, called the proteome. Even though all cells of a multicellular organism have the same set of genes, cells in various tissues produce different sets of proteins. Thus, the genome is constant, but the proteome varies and is dynamic within an organism. Proteomics may be used to study which proteins are expressed under various conditions within a single cell type or to compare protein expression patterns between different organisms.

A recent and developing proteomic analysis relies on identifying proteins called biomarkers, whose expression is affected by the disease process. Biomarkers are currently being used to detect various forms of cancer as well as infections caused by pathogens such as Yersinia pestis and Vaccinia virus.[1]

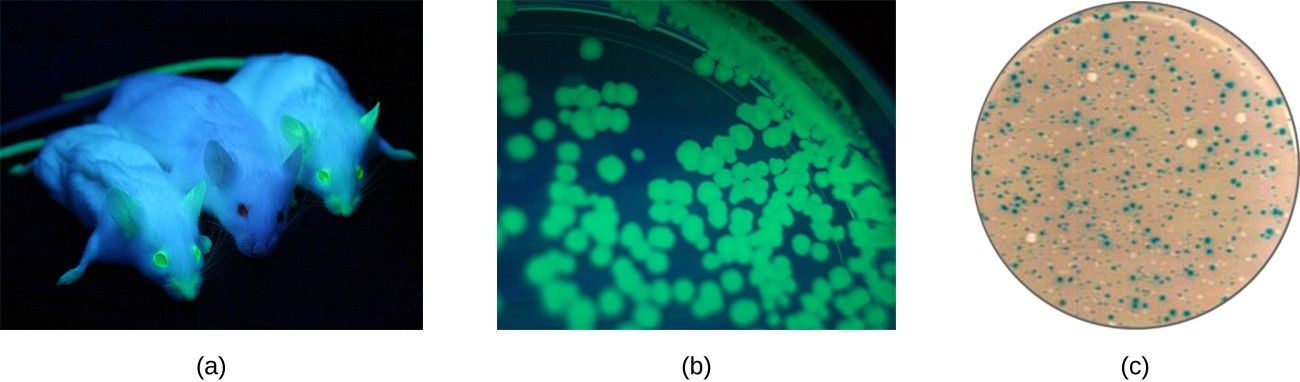

Additionally, researchers can use reverse genetics, a technique related to classic mutational analysis, to determine the function of specific genes. Classic methods of studying gene function involved searching for the genes responsible for a given phenotype. Reverse genetics uses the opposite approach, starting with a specific DNA sequence and attempting to determine what phenotype it produces. Alternatively, scientists can attach known genes (called reporter genes) that encode easily observable characteristics to genes of interest, and the location of expression of such genes of interest can be easily monitored. This gives the researcher important information about what the gene product might be doing or where it is located in the organism. A common reporter genes includes the gene encoding the jellyfish protein green fluorescent protein (GFP) whose activity can be visualized in colonies under ultraviolet light exposure (Figure 8.2).

![]()

- How is genomics different from traditional genetics?

- If you wanted to study how two different cells in the body respond to an infection, what –omics field would you apply?

- What are the biomarkers uncovered in proteomics used for?

Recombinant DNA Technology and Pharmaceutical Production

Genetic engineering has provided a way to create new pharmaceutical products called recombinant DNA pharmaceuticals. Such products include antibiotic drugs, vaccines, and hormones used to treat various diseases. Table 8.1 lists examples of recombinant DNA products and their uses.

For example, the naturally occurring antibiotic synthesis pathways of various Streptomyces spp., long known for their antibiotic production capabilities, can be modified to improve yields or to create new antibiotics through the introduction of genes encoding additional enzymes. More than 200 new antibiotics have been generated through the targeted inactivation of genes and the novel combination of antibiotic synthesis genes in antibiotic-producing Streptomyces hosts.[2]

Genetic engineering is also used to manufacture subunit vaccines, which are safer than other vaccines because they contain only a single antigenic molecule and lack any part of the genome of the pathogen (see Vaccines). For example, a vaccine for hepatitis B is created by inserting a gene encoding a hepatitis B surface protein into a yeast; the yeast then produces this protein, which the human immune system recognizes as an antigen. The hepatitis B antigen is purified from yeast cultures and administered to patients as a vaccine. Even though the vaccine does not contain the hepatitis B virus, the presence of the antigenic protein stimulates the immune system to produce antibodies that will protect the patient against the virus in the event of exposure.[3][4]

Genetic engineering has also been important in the production of other therapeutic proteins, such as insulin, interferons, and human growth hormone, to treat a variety of human medical conditions. For example, at one time, it was possible to treat diabetes only by giving patients pig insulin, which caused allergic reactions due to small differences between the proteins expressed in human and pig insulin. However, since 1978, recombinant DNA technology has been used to produce large-scale quantities of human insulin using E. coli in a relatively inexpensive process that yields a more consistently effective pharmaceutical product. Scientists have also genetically engineered coli capable of producing human growth hormone (HGH), which is used to treat growth disorders in children and certain other disorders in adults. The HGH gene was cloned from a cDNA library and inserted into E. coli cells by cloning it into a bacterial vector. Eventually, genetic engineering will be used to produce DNA vaccines and various gene therapies, as well as customized medicines for fighting cancer and other diseases.

|

Recombinant DNA Product |

Application |

|---|---|

|

Atrial natriuretic peptide |

Treatment of heart disease (e.g., congestive heart failure), kidney disease, high blood pressure |

|

DNase |

Treatment of viscous lung secretions in cystic fibrosis |

|

Erythropoietin |

Treatment of severe anemia with kidney damage |

|

Factor VIII |

Treatment of hemophilia |

|

Hepatitis B vaccine |

Prevention of hepatitis B infection |

|

Human growth hormone |

Treatment of growth hormone deficiency, Turner’s syndrome, burns |

|

Human insulin |

Treatment of diabetes |

|

Interferons |

Treatment of multiple sclerosis, various cancers (e.g., melanoma), viral infections (e.g., Hepatitis B and C) |

|

Tetracenomycins |

Used as antibiotics |

|

Tissue plasminogen activator |

Treatment of pulmonary embolism in ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction |

![]()

- What products have been developed using genetic engineering?

- Explain how microorganisms can be engineered to produce vaccines.

RNA Interference Technology

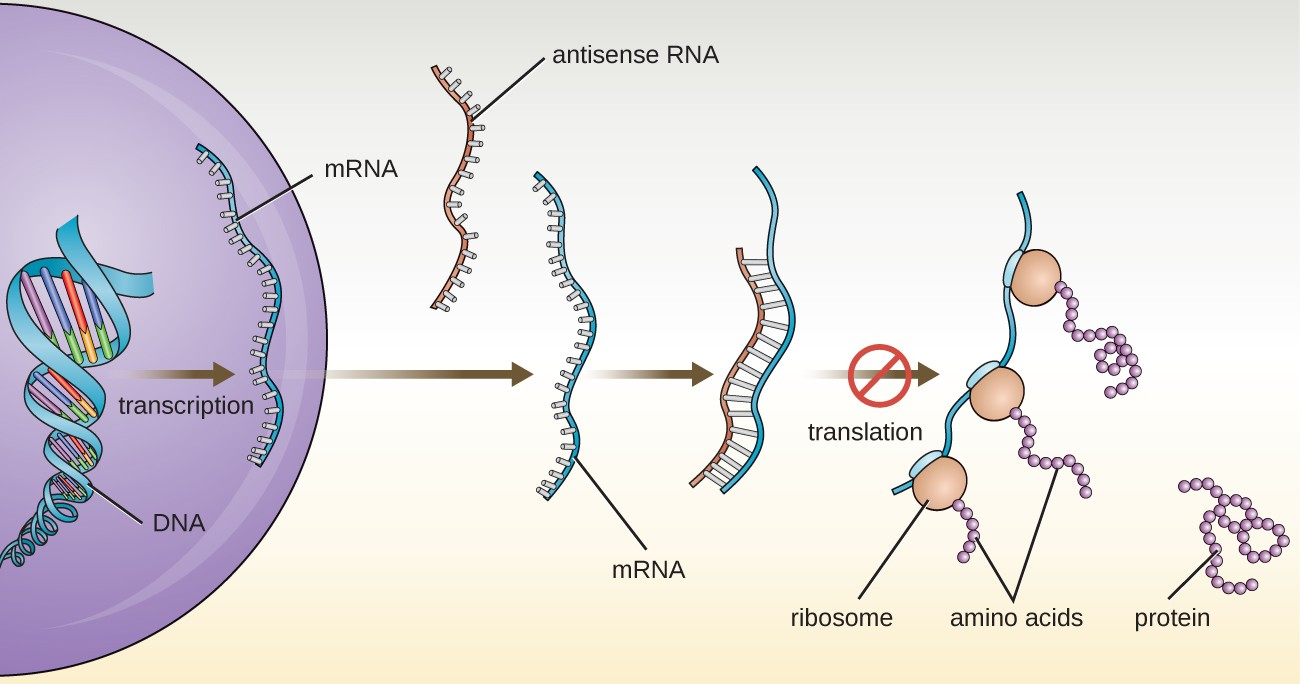

Cells produce several types of small noncoding RNA molecules that are involved in the regulation of gene expression. These include antisense RNA molecules, which are complementary to regions of specific mRNA molecules found in both prokaryotes and eukaryotic cells. Non-coding RNA molecules play a major role in RNA interference (RNAi), a natural regulatory mechanism by which mRNA molecules are prevented from guiding the synthesis of proteins. RNA interference of specific genes results from the base pairing of short, single-stranded antisense RNA molecules to regions within complementary mRNA molecules, preventing protein synthesis. Cells use RNA interference to protect themselves from viral invasion, which may introduce double-stranded RNA molecules as part of the viral replication process (Figure 8.3).

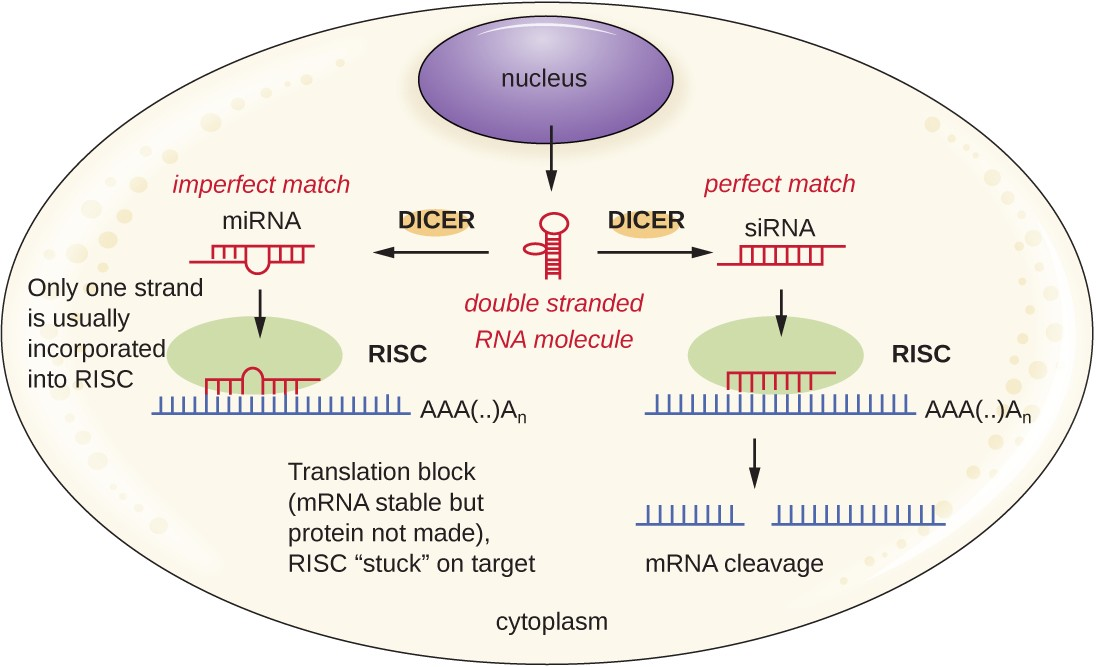

Researchers are currently developing techniques to mimic the natural process of RNA interference as a way to treat viral infections in eukaryotic cells. RNA interference technology involves using small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) or microRNAs (miRNAs) (Figure 8.4). siRNAs are completely complementary to the mRNA transcript of a specific gene of interest while miRNAs are mostly complementary. These double-stranded RNAs are bound to DICER, an endonuclease that cleaves the RNA into short molecules (approximately 20 nucleotides long). The RNAs are then bound to RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), a ribonucleoprotein. The siRNA-RISC complex binds to mRNA and cleaves it. For miRNA, only one of the two strands binds to RISC. The miRNA-RISC complex then binds to mRNA, inhibiting translation. If the miRNA is completely complementary to the target gene, then the mRNA can be cleaved. Taken together, these mechanisms are known as gene silencing.

- Mohan Natesan, and Robert G. Ulrich. “Protein Microarrays and Biomarkers of Infectious Disease.” International Journal of Molecular Sciences 11 no. 12 (2010): 5165–5183. ↵

- Jose-Luis Adrio and Arnold L. Demain. “Recombinant Organisms for Production of Industrial Products.” Bioengineered Bugs 1 no. 2 (2010): 116–131. ↵

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. “Types of Vaccines.” 2013. http://www.vaccines.gov/more_info/types/#subunit. Accessed May 27, 2016. ↵

- The Internet Drug List. Recombivax. 2015. http://www.rxlist.com/recombivax-drug.htm. Accessed May 27, 2016. ↵