19.2 Microbial Diseases of the Mouth and Oral Cavity

Learning Objectives

- Explain the role of microbial activity in diseases of the mouth and oral cavity

- Compare the major characteristics of specific oral diseases and infections

Despite the presence of saliva and the mechanical forces of chewing and eating, some microbes thrive in the mouth. These microbes can cause damage to the teeth and can cause infections that have the potential to spread beyond the mouth and sometimes throughout the body.

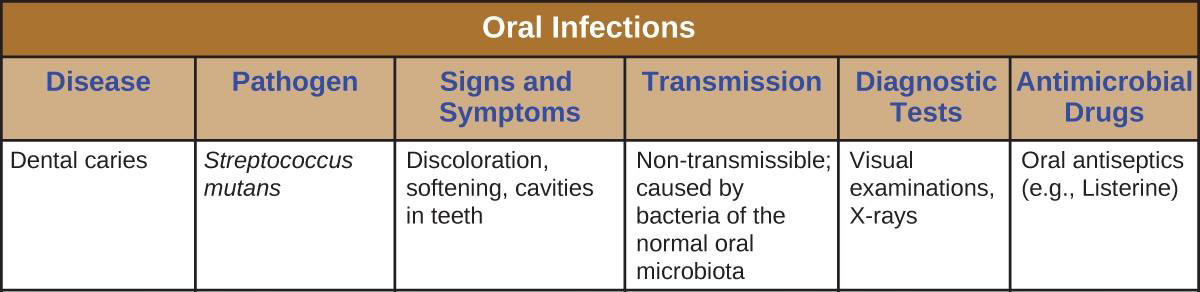

Dental Caries

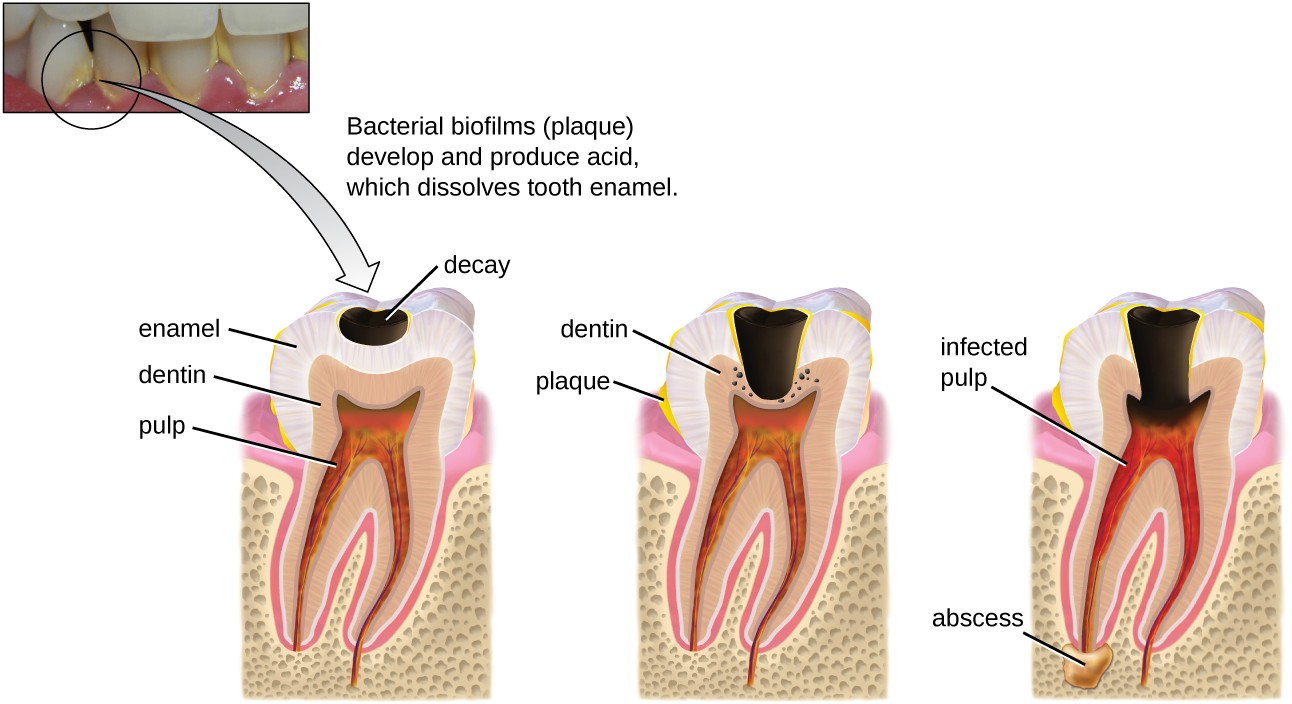

Cavities of the teeth, known clinically as dental caries, are microbial lesions that cause damage to the teeth. Over time, the lesion can grow through the outer enamel layer to infect the underlying dentin or even the innermost pulp. If dental caries are not treated, the infection can become an abscess that spreads to the deeper tissues of the teeth, near the roots, or to the bloodstream.

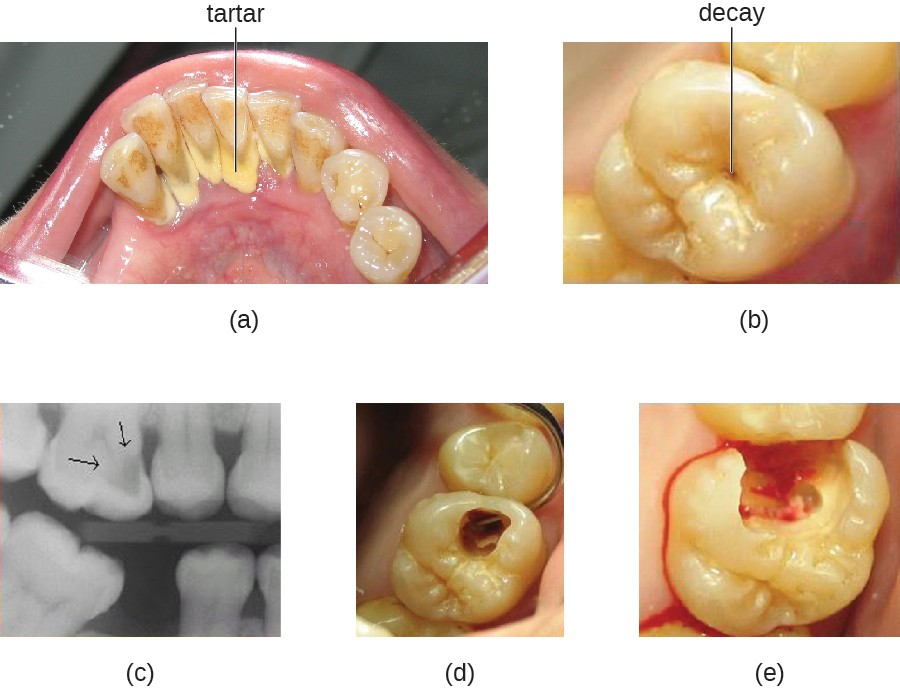

Tooth decay results from the metabolic activity of microbes that live on the teeth. A layer of proteins and carbohydrates forms when clean teeth come into contact with saliva. Microbes are attracted to this food source and form a biofilm called plaque. The most important cariogenic species in these biofilms is Streptococcus mutans. When sucrose, a disaccharide sugar from food, is broken down by bacteria in the mouth, glucose and fructose are produced. The glucose is used to make dextran, which is part of the extracellular matrix of the biofilm. Fructose is fermented, producing organic acids such as lactic acid. These acids dissolve the minerals of the tooth, including enamel, even though it is the hardest material in the body. The acids work even more quickly on exposed dentin (Figure 19.7). Over time, the plaque biofilm can become thick and eventually calcify. When a heavy plaque deposit becomes hardened in this way, it is called tartar or dental calculus (Figure 19.8). These substantial plaque biofilms can include a variety of bacterial species, including Streptococcus and Actinomyces species.

Some tooth decay is visible from the outside, but it is not always possible to see all decay or the extent of the decay. X-ray imaging is used to produce radiographs that can be studied to look for deeper decay and damage to the root or bone (Figure 19.8). If not detected, the decay can reach the pulp or even spread to the bloodstream. Painful abscesses can develop.

To prevent tooth decay, prophylactic treatment and good hygiene are important. Regular tooth brushing and flossing physically removes microbes and combats microbial growth and biofilm formation. Toothpaste contains fluoride, which becomes incorporated into the hydroxyapatite of tooth enamel, protecting it against acidity caused by fermentation of mouth microbiota. Fluoride is also bacteriostatic, thus slowing enamel degradation. Antiseptic mouthwashes commonly contain plant-derived phenolics like thymol and eucalyptol and/or heavy metals like zinc chloride. Phenolics tend to be stable and persistent on surfaces, and they act through denaturing proteins and disrupting membranes.

Regular dental cleanings allow for the detection of decay at early stages and the removal of tartar. They may also help to draw attention to other concerns, such as damage to the enamel from acidic drinks. Reducing sugar consumption may help prevent damage that results from the microbial fermentation of sugars. Additionally, sugarless candies or gum with sugar alcohols (such as xylitol) can reduce the production of acids because these are fermented to nonacidic compounds (although excess consumption may lead to gastrointestinal distress). Fluoride treatment or ingesting fluoridated water strengthens the minerals in teeth and reduces the incidence of dental caries.

If caries develop, prompt treatment prevents worsening. Smaller areas of decay can be drilled to remove affected tissue and then filled. If the pulp is affected, then a root canal may be needed to completely remove the infected tissues to avoid continued spread of the infection, which could lead to painful abscesses.

![]()

- Name some ways that microbes contribute to tooth decay.

- What is the most important cariogenic species of bacteria?

Micro Connections

Healthy Mouth, Healthy Body

Good oral health promotes good overall health, and the reverse is also true. Poor oral health can lead to difficulty eating, which can cause malnutrition. Painful or loose teeth can also cause a person to avoid certain foods or eat less. Malnutrition due to dental problems is of greatest concern for the elderly, for whom it can worsen other health conditions and contribute to mortality. Individuals who have serious illnesses, especially AIDS, are also at increased risk of malnutrition from dental problems.

Additionally, poor oral health can contribute to the development of disease. Increased bacterial growth in the mouth can cause inflammation and infection in other parts of the body. For example, Streptococcus in the mouth, the main contributor to biofilms on teeth, tartar, and dental caries, can spread throughout the body when there is damage to the tissues inside the mouth, as can happen during dental work. S. mutans produces a surface adhesin known as P1, which binds to salivary agglutinin on the surface of the tooth. P1 can also bind to extracellular matrix proteins including fibronectin and collagen. When Streptococcus enters the bloodstream as a result of tooth brushing or dental cleaning, it causes inflammation that can lead to the accumulation of plaque in the arteries and contribute to the development of atherosclerosis, a condition associated with cardiovascular disease, heart attack, and stroke. In some cases, bacteria that spread through the blood vessels can lodge in the heart and cause endocarditis (an example of a focal infection).