1 Introduction

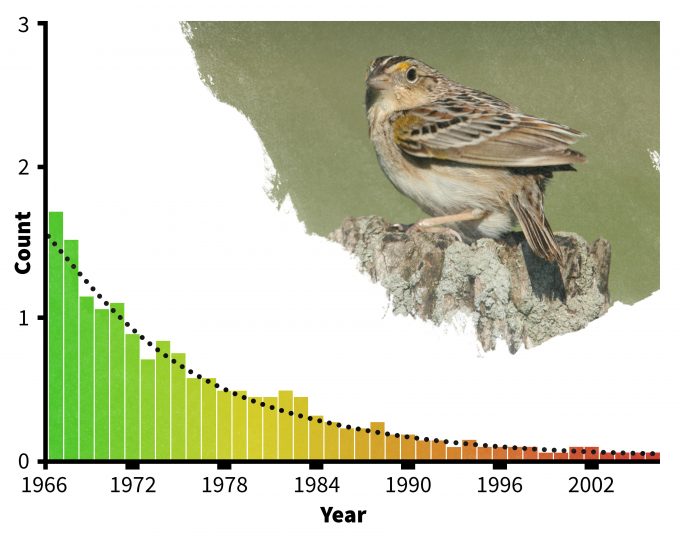

There are many reasons to enter into a monitoring program, but the reasons must be well-considered before doing so. Long-term monitoring takes time, money and effort that could be spent in other endeavors such as management, research, and outreach. Monitoring is conducted most often when the resources of concern are of high economic or social value, part of a legally-mandated planning process, the result of a judicial decision, or the result of a crisis. Many times it is a combination of these factors that gives rise to a monitoring program. In addition, monitoring may be conducted as part of a formal research program where long-term trends in an ecologically or socially important response variable are the most important outcome. Also if a population or natural community seems rare or there is the perception by scientists or stakeholders that a decline is evident, then monitoring may be called for to clarify the perception. Most often monitoring programs are designed to help managers and policy makers make more informed decisions. Monitoring allows decisions to be based less on beliefs and more on facts. We may believe that grasshopper sparrows in New England are decreasing in abundance because grasslands are being converted to housing (Figure 1.1). Only after a rigorous, unbiased monitoring program has been in place can we say that yes, indeed, the population seems to be declining (Figure 1.2) and that the decline is associated with the loss of grasslands. However, we cannot ascribe the cause of the decline to grassland loss unless a more rigorous research program is put into place. Monitoring provides the hypothesis for the decline; research is often implemented in a structured before-after control-impact design assesses cause-and-effect relationships.

Monitoring Resources of High Value

Typically we think of monitoring as something that is done because we value a resource and we do not want to lose it, or we wish to maximize it. For economic goods and services, we often will monitor so that we can maximize profit margins while minimizing adverse effects. But economics are not the only values placed on resources. Monitoring the haze present over the Grand Canyon is in response to aesthetic values as well as human health concerns. Ottke et al. (2000) described the importance of considering cultural values in natural resources monitoring and provided examples from 13 case studies around the world. As an example, rarity, in of itself, is often used to initiate a monitoring program. Rare species, populations, or gene pools may be valued sufficiently to initiate and maintain a monitoring program to ensure that these rare organisms persist. Regardless of the motivation for initiating a monitoring program, all require a monitoring approach that allows unbiased sampling, assessment of trends over time, the potential for extrapolation to unsampled areas, and (in some cases) comparisons between areas managed in different ways.

Economic Value

Monitoring the antler size of white-tailed deer killed on a property leased for hunting, crop loss from Canada goose foraging, or monitoring tree growth on a timber industry landholding all represent examples of specific resources that the owner or manager may wish to manage for economic gain. Economic value commonly drives monitoring programs at a variety of scales. The U.S. Forest Service Forest Inventory and Analysis program is a good example of a well-structured national monitoring program that was initiated to assess the timber value, primarily economic, on non-federal lands in the US (Sheffield et al. 1985). Over time, however, the program evolved into a multi-resource monitoring program and has since been used to assess other natural resource values on non-federal forest lands (McComb et al. 1986). Similarly, but on a local scale, farmers may monitor the effects of birds on corn seed depredation, or deer on soybean production. Communities in Africa are directly involved in monitoring programs to assess the potential for crop damage and then work with authorities to find ways of minimizing the adverse effects of having African elephants in their fields (Songorwa 1999).

Social, Cultural, and Educational Value

Monitoring systems that provide the basis for resource management decisions are often initiated and maintained to support resources held in the public trust. Yet not all resources held in the public trust are monitored. While the selection of resources that are monitored is partially driven by economics, the perceptions, concerns, and cultural values of society also play a role. Programs such as the Breeding Bird Survey Program (Sauer et al. 2007), the North American Amphibian Monitoring Program run by the USGS, the Monitoring Avian Productivity and Survivorship (MAPS) Program created by The Institute for Bird Populations in 1989, and the EPA’s program of monitoring and assessing water quality all represent organized, large-scale efforts to acquire data to make more informed resource management decisions. Each has indicators chosen due to a variety of social, cultural, and economic values.

Programs such as these that are supported by federal agencies also have a long-standing reputation for monitoring various biophysical components of ecosystems. The Long Term Ecological Research (LTER) program maintains sites throughout the US that provide long-term information on ecosystem structure and function. More recently the National Ecological Observatory Network (NEON) was initiated as a continental-wide program to help understand the impacts of climate change, land-use change, and invasive species on ecosystems and ecosystem services. The importance of these data may not be apparent for years or decades, but the educational benefit that accrues over time may be invaluable. Consider the impact of having monitored carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, ice cover, and plant phenology (the timing of flowering and fruiting) that collectively provided evidence for climate change and insights into likely changes in biota.

Economic Accountability

When push comes to shove, however, economics is almost always the horse that pulls the cart in natural resource programs. When an instructor wants to monitor the progress of a student in learning material she gives a test, or asks for a paper or report. When members of Congress on an Appropriations Committees allocate millions of dollars to the US Fish and Wildlife Service to ensure protection of endangered species, they want to know that the money is being spent wisely and that the actions being taken are effective. Indeed, the General Accounting Office (GAO) has as its primary responsibility monitoring of appropriations to ensure that the taxpayers’ dollars are being spent wisely by our federal agencies (GAO 2007). In both these cases, whether a teacher or an appropriations committee, the supervisory power is asking for a sense of accountability that can only be ascertained through careful monitoring.

In a 2007 report developed jointly by the GAO and the National Academy of Sciences, they state, “One of the greatest challenges facing the United States in the 21st century is sustaining our natural resources and safeguarding our environmental assets for future generations while promoting economic growth and maintaining our quality of life”, if that is even possible (Czech 2006). “To manage natural resources effectively and efficiently, policymakers need information and methods to analyze the dynamic interplay between the economy and the environment. Enhancing the information used to make sound decisions can be facilitated by developing national environmental assessments. These assessments provide a framework for organizing information on the status, use, and value of natural resources and environmental assets, as well as on expenditures on environmental protection and resource management.” (GAO 2007). Forums such as this one (GAO 2007) provide a strategic and economic framework for the integration of monitoring efforts that span agencies and resources. Whether it is a student taking a quiz or a researcher managing a multi-million dollar monitoring program, the goal is to find the answer to a simple question: “How are we doing?”

So who cares about monitoring and the millions spent on it? You should. This is because public funds often drive monitoring programs and resources held in the public trust are frequently the targets being monitored! Those who represent you in Congress and in State legislatures, local planning boards, and NGO Boards of Directors should also care about monitoring. Government agencies and NGOs have issued “State of the Environment” reports for countries such as the U.S., Australia, and Canada (Beeton 2006, Environment Canada 1996, Heinz Center 2002). A compilation of over 50 such reports has been assembled by the National Council on Science, Policy and the Environment. These reports are based on whatever monitoring data are available to directly report changes over time in important resources or indicators of those resources. Similar reports, although less common, are also beginning to emerge from scientists working in developing nations (Guarderas et al. 2008).

In addition to these broad ‘State of the Environment’ reports, policy-makers and elected officials often demand that agencies provide periodic updates on the effectiveness of their work. Is the US taxpayer getting the “Biggest bang for the buck?” “Is our management effective?” “Why should we continue to pay for collecting data year after year?” According to managers and regulators employed by state and federal agencies, NGOs, and industries, accountability has become a key component of their work. Industry often is most concerned about the economic efficiency of certain management actions. If management actions are not as effective as planned and the monitoring influences the bottom line (it will), then industry will demand a change to more efficient and effective management and monitoring. A timber company may wish to ensure that the goals of leaving a riparian buffer strip are met to the extent that it was worth foregoing the profits, or an NGO may wish to ensure that their limited funds are being effective in restoring a prairie ecosystem. Hence, from purely a practical standpoint, monitoring questions are often of utmost importance to a manager because they are designed to assess how far her expenses go toward meeting her goals. At the end of the day, the results of such assessments will determine whether or not a management action is viable.

But monitoring is not free. It costs money to do it correctly. Hence, monitoring efforts are also driven by the money available to spend on monitoring. Indeed, whether we like it or not, budgets determine our options in resource management, and funds for monitoring are always among the first parts of the budget to be critically reviewed. The system tends to encourage short sightedness: in many budget planning processes it is easier to acquire funding for new innovative projects than to continue ongoing efforts. Getting funding to build a new visitor center at a refuge may be easier than maintaining it. Getting a monitoring program initiated may be easier than finding the funding to continue it for a long enough period of time to ensure that the results are used. The implications associated with continuing a commitment to a monitoring program must be accounted for in the design of monitoring programs.

Monitoring as a Part of Resource Planning

Monitoring is also a key part of the planning process used by federal agencies, many NGOs, and some industries. People make plans. You have plans for the weekend, for your next vacation, or for your retirement. Plans are based on assumptions, some of which may turn out to not be correct, and despite the best plans, there are often uncertainties that arise to disrupt plans. If you get a flat tire on your car then your plans change for the weekend. Monitoring the function of your car by regularly checking the tire pressure may have prevented that flat. A US Fish and Wildlife Service Refuge may have a refuge management plan, but if an invasive species should establish itself unexpectedly, then the plan may have to change. Monitoring the changes in the primary structures and functions of the Refuge (plant communities, distributions of species, erosion, sedimentation, rates of change in species dominance) may allow quick response and rapid removal of the invasive that may not be possible if one must wait for the next planning cycle. Hence monitoring is almost always included as a key component of natural resource (and other) plans.

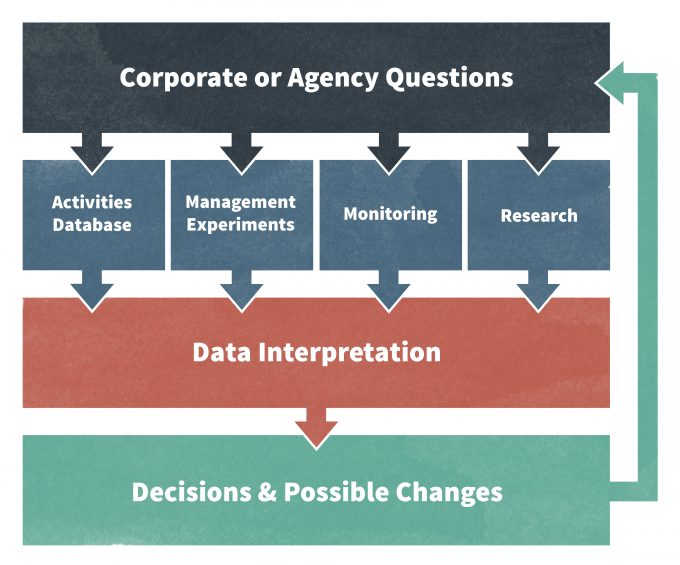

Certainly there are specific guidelines regarding monitoring resources on federal landholdings such as USFWS National Wildlife Refuges (Schroeder 2006). Yet the specifics of the monitoring goals, strategies and interpretation are often left somewhat vague in Comprehensive Conservation Plans (CCPs), National Forest Management Plans, and many others. Clearly there are exceptions to this (see the Northwest Forest Plan example below), but quite often the development of a detailed monitoring plan comes after the management plan has been developed and approved and not developed as an integral component of the management plan. If we truly do care if we are being effective in our management and if we are spending money wisely to achieve goals then the monitoring plan should be an integral component of a management plan (Figure 1.3).

From the standpoint of achieving planning goals that relate to wildlife species and their habitats, a properly designed monitoring effort allows managers and biologists to understand the long-term dependency of selected species on various habitat elements. Habitat is defined as the set of resources that support a viable population over space and through time (McComb 2007). Identifying those key resources, or reliable indicators of them, can provide information on how a species may respond to changes. The challenge when developing a monitoring plan is to assess the impacts of the dynamic nature of resource availability on a species. In other words, we must assess if changes in occurrence, abundance, or fitness in a population are independent from or related to changes in the availability of resources assumed to contribute to the species’ habitat (Cody 1985).

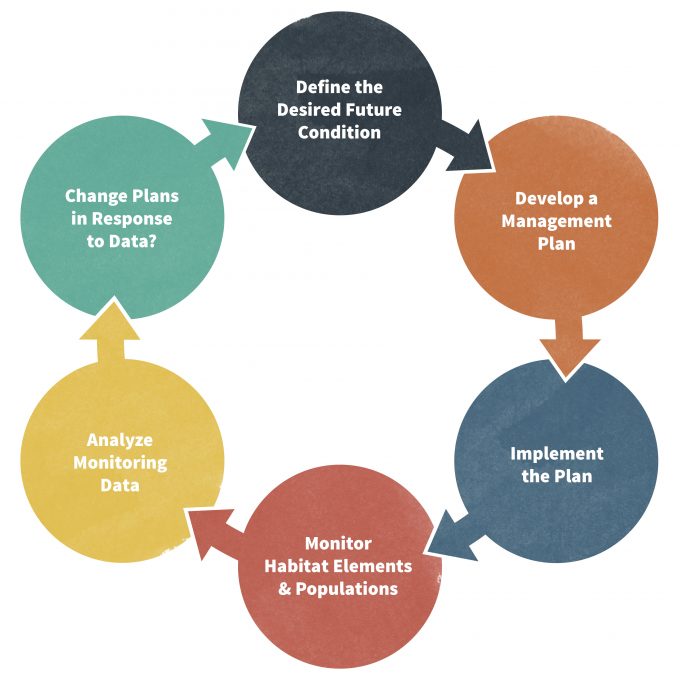

Even with timely planning, implementation of any natural resources plan is done with some uncertainty that the actions will achieve the desired results. Nothing in life is certain (except death!). But by incorporating uncertainty into a project we can reduce many of the risks associated with not knowing. Managers should expect to change plans following implementation based on measurements taken to see if the implemented plan is meeting their needs. If not, then mid-course corrections will be necessary. Many natural resource management organizations in North America use some form of adaptive management as a way of anticipating changes to plans and continually improving plans (Walters 1986) (Figure 1.4).

Monitoring in Response to a Crisis

Monitoring to address a perceived crisis has been repeated with many species: northern spotted owls, red-cockaded woodpeckers, and nearly every other species that have been listed as threatened or endangered in the US under the Endangered Species Act or similar state legislation. Although many of these monitoring programs were developed during a period of social and ecological turmoil, many are also remarkably well structured because the stakes are so high. For instance in the case of the northern spotted owl, the butting heads of high economic stakes and the palpable risk of loss of a species culminated in a crisis that spawned one of the most comprehensive and costly wildlife monitoring programs in US history: the monitoring outcome from the Northwest Forest Plan (NWFP). The NWFP was designed to fulfill the mandate of the Endangered Species Act by enabling recovery of the federally endangered northern spotted owls and also addressed other species associated with late successional forests over 10 million ha of federal forest land in the Pacific Northwest of the US. In his Record of Decision regarding the plan, Judge Dwyer emphasized the importance of effectiveness monitoring to the NFWP, and monitoring has been an integral part of it since its implementation; “Monitoring is central to the [Plan’s] validity. If it is not funded, or done for any reason, the plan will have to be reconsidered.” (USDA, USDI 1994; Dwyer 1994).

One component of NWFP effectiveness monitoring was a plan for the northern spotted owl. The northern spotted owl monitoring program is one of the most intensive avian population monitoring efforts in North America. The purpose of the plan is to record data that reveals trends in spotted owl populations and habitat to assess the success of the NWFP at reversing the population decline for this species (Lint 2005). To this end, the specific objectives of the monitoring program are to (1) assess changes in population trend and demographic performance of spotted owls on federally administered forest land within the range of the owl, and (2) assess changes in the amount and distribution of nesting, roosting, and foraging habitat (owl habitat) and dispersal habitat for spotted owls on federally administered forest land (Lint 2005).

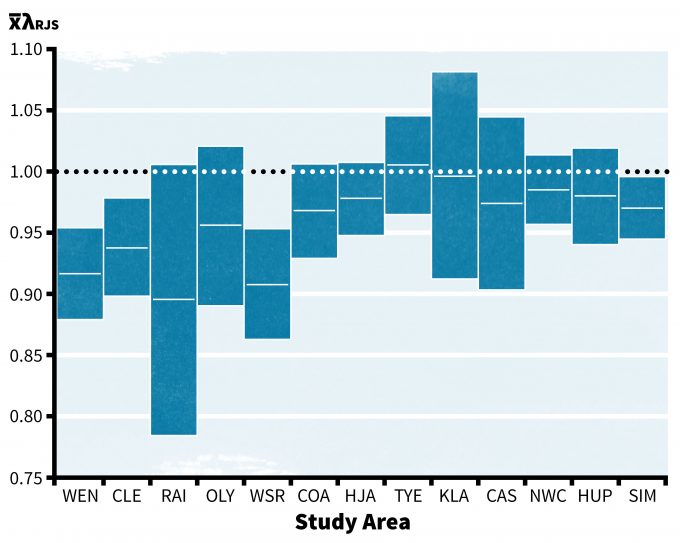

Population monitoring for northern spotted owls encompasses 11 demographic study areas from northern Washington to northern California. Three parameters are estimated from the data to assess trends: Survival, fecundity and lambda (population rate of change). As you can see from Figure 1.5 the trends in population change varied quite widely among the demographic study areas, lending support for use of these study areas as strata within the monitoring framework.

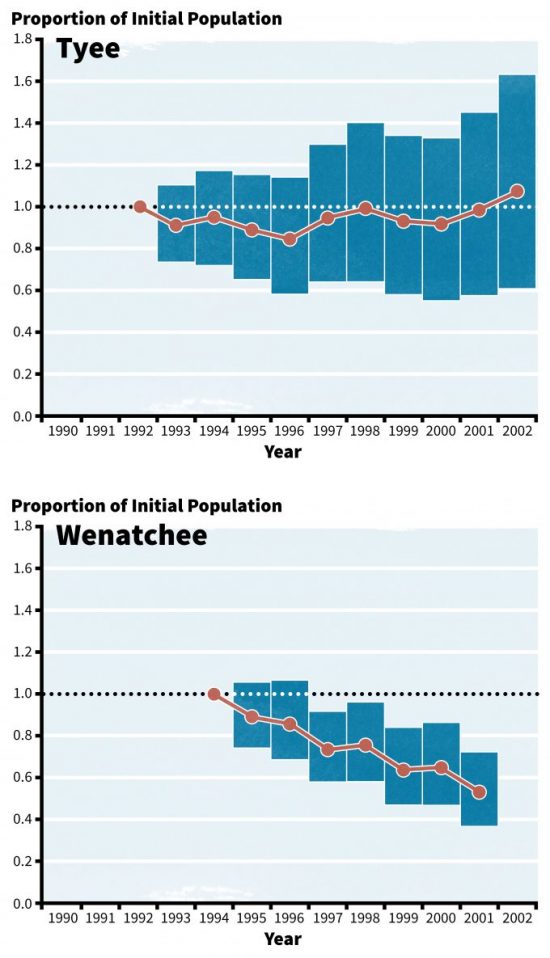

Populations seem to be declining on the Wenatchee (WEN) site in the eastern Washington Cascades, but remaining somewhat stable on the Tyee site in the Oregon Coastal Ranges (Figure 1.6). In a case such as this, with such wide differences in trends, where does that leave managers regarding use of these data? The magnitude of population declines on the Wenatchee study site raises significant concerns and the first reaction is that the plan has failed.

But the Tyee data indicate that the plan is succeeding. So which is it? Lint (2005) concluded that it is too early to say if the plan has failed or succeeded because restoration of habitat for the species takes longer than the 10 years that monitoring had occurred. But monitoring also revealed other stressors on the population such as competition with barred owls and the potential for increased mortality from West Nile virus, further complicating the interpretation of the monitoring data. Indeed, even with the most rigorous design, uncertainty is inevitable.

Given the importance of economic considerations, the question begs to be asked: Was the monitoring worth over $2 million spent per year (Lint 2001)? Consider the price that taxpayers would pay for not monitoring. First, we could easily lose a species due to plan failure or from other more contemporary stressors. Second, the NWFP would likely be challenged in court again, costing the taxpayers a considerable amount in legal fees. Third, we learned much more about the species and drivers of populations by having collected these data so that the results can (and do) influence how managers make decisions. We also have research-quality data to address future issues with this species and others like it. But the answer to the question, “Was the monitoring worth it…” is, clearly, “It depends”. It depends on who is doing the evaluating. Some segments of society will answer “Of course it was worth it”. Others will say that “It had to be done legally”. Still others would say that, “The money would have been better spent on addressing the needs of the displaced forest workers.” All are valid points. And the data collected provide each segment of society information with which to base their arguments. Thus, although the cost is the deciding factor, societal values can never be ignored; it is after all society who grants us a social license to manage animals and their habitats.

Monitoring in Response to Legal Challenges

Effectiveness monitoring was strongly suggested by Judge Dwyer in his Record of Decision on the implementation of the NWFP over 10 million ha of federal lands in the Pacific Northwest. His decision emphasized the importance of monitoring as a component of this multi-agency plan and influenced plan design. But legal decisions can influence not only the structure of a plan, but also influence how and sometimes determine if the plan and all of its principal components, including monitoring, are implemented.

If a resource is valued highly enough, litigation may be enacted that results in judicial decisions that influence the likelihood that monitoring will be conducted. For instance, there are times when monitoring is an integral part of a written plan, but agencies and managers do not have the funding to initiate or maintain a monitoring program. Concerned citizens may file a lawsuit that results in the re-appropriation of public funds to provide for monitoring. A slightly different example of this involves the McLean Game Refuge, a 1700-ha private tract located in north-central Connecticut in the Towns of Granby and Simsbury. The Refuge was established in 1932 by bequest of former Governor and Senator of Connecticut, George McLean. Decisions about Refuge use, maintenance, and management are made by a manager under the oversight of a Board of Trustees. A proposal to use partial cutting approaches (thinning, group selection, and shelterwood methods) in the McLean Game Refuge in 2001 met with significant opposition by local residents. The decision to manage the forest was based on suggestions from natural resources professionals that active management could diversify forest structure and composition and hence could lead to more diverse animal communities. Following a public meeting and a series of hearings in civil court, this opposition culminated in a judicial ruling that allowed the Refuge Manager to proceed with the harvest. However, the judge also encouraged the manager to monitor the changes in animal species composition and habitat so that any future harvests could be informed by the information gained from the monitoring effort. The judicial decision not only stipulated that monitoring ought to be carried out but also influenced how managers monitor animals and habitat. Monitoring of bird communities and habitat structure and composition was initiated prior to the timber harvest and again after the harvests. Monitoring indicated that following one growing season after harvests, detections of seven species were higher in the thinned stands while detections of wood thrushes were higher in uncut controls. Was the cutting the correct thing to do? That depends on who is asking the question, but now the debate can be more informed than it was in 2001.

Adaptive Management

Although adaptive management has already been introduced above, it deserves to be addressed at greater length because it is central to successful monitoring and management practices. Adaptive management is a process to find better ways of meeting natural resource management goals by treating management as a hypothesis (Figure 1.4). The results of the process also identify gaps in our understanding of ecosystem responses to management activities. The adaptive management process incorporates learning into the management planning process, and the data collected from the monitoring conducted within this framework provide feedback about the effectiveness of preferred or alternative management practices. The information gained can help to reduce the uncertainty associated with ecosystem and human system responses to management. Adaptive management has been classified as both active and passive (Walters and Holling 1990).

Passive adaptive management is a process where the ‘best’ management option and associated actions are identified, implemented and monitored. The monitoring may or may not include unmanaged reference areas as points of comparison to the managed areas. The changes observed over time in the managed and reference areas are documented and the information is used to alter future plans. Hence the manager learns by managing and monitoring, but the information that is gained from the process is limited, especially if reference areas are not used. Without reference areas we do not know if changes over time are due to management or some other exogenous factors.

Active adaptive management treats the process of management much more like a scientific experiment than passive adaptive management. Under active adaptive management, management approaches are treated as hypotheses to be tested. The hypotheses are developed specifically to identify knowledge gaps and management actions are designed to fill those gaps. Typically, hypotheses are developed based on modeling the responses of the system to management (e.g. using forest growth models, or landscape dynamics models). Management is then conducted and key states and processes are monitored to see if the system responded as it was predicted. Reference areas are also monitored and the data from these areas are used as controls to compare responses of ecosystems and human systems to management. By collecting monitoring data in a more structured hypothesis-testing framework, system responses can be quantified and used to identify probabilities associated with achieving desired outcomes in the future. Whereas passive adaptive management is somewhat reactive in approach (reacting to monitoring data), active adaptive management is proactive and follows a formal experimental design.

Adaptive management generally consists of six major steps (Figure 1.4):

- Set goals (define the desired future condition)

- Develop a plan to meet the goals based on best current information

- Implement the plan

- Monitor the responses of key states and processes to the plan

- Analyze the monitoring data

- Adjust the plan based on results from analysis the monitoring data.

Before anything is implemented or monitored, the problem must be assessed both inside and outside the organization. Public involvement in the process from the very beginning is key to identification of points of concern and uncertainty. With information in hand from a series of listening sessions, the cycle can more formally begin. Important components include designing a plan considered to be the preferred or best plan among several alternative plans, identifying reference areas to use as points of comparison, and implementing and monitoring the plan to learn from the management actions.

An Example of Monitoring and Use of Adaptive Management

When we discussed the 1993 NWFP above, the economic and social impacts of regulating logging to conserve or foster late-successional habitat were not adequately addressed. The efforts of the NWFP’s authors to end the stalemate between segments of the population who supported continued timber management on federal lands, and those who saw federal lands as refuges for late-successional and old-growth species, particularly the northern spotted owl, are a key component of the story.

Indeed, the objectives of the NWFP as a whole are threefold:

- Protecting and enhancing habitat for mature and old-growth forests and related species.

- Restoring and maintaining the ecological integrity of watersheds and aquatic ecosystems.

- Producing a predictable level of timber sales, special forest products, livestock grazing, minerals and recreational opportunities, as well as maintaining the stability of rural communities and economies.

Using an adaptive management approach, a monitoring program was established to better understand the extent to which management attains these objectives and to more fully grasp the interplay among them. The monitoring program relies on both internal and external sources of data. For instance, internal data were collected directly by the Regional Monitoring Team or by cooperators funded through the monitoring program. External data were collected by programs such as the U.S. Forest Service’s Forest Inventory and Analysis Program. Data include information on populations and (occasionally) fitness of key species as well as information on the changes in area of old forests, socioeconomic conditions in the region, and watershed condition (Haynes et al. 2006). Recently 10-year results were released and researchers can now make the first of these assessments (Haynes et al. 2006). This wealth of information is readily available to managers and the public and it helps adapt past and inform new decisions made on both public and adjacent private lands in the Pacific Northwest (Spies et al. 2007)

Summary

Monitoring is done for a variety of reasons, but at its core, monitoring is done to provide information and make more informed decisions. In many instances, monitoring is done either as a legal requirement or in response to a crisis. As species become listed as threatened or endangered, as economically important species (e.g., deer) decline in number, or pest species that jeopardize human health increase in number, then immediate action and monitoring are often called for by managers and the public. If challenged in court then a judge can have considerable influence over the establishment and continuation of a monitoring program.

In other cases a manager, landowner or stakeholder may simply realize that knowing how a resource is changing over time can mean that management may be more effective in the future. Foresters certainly take this approach by using continuous forest inventory, but wildlife managers also have recognized the importance of long-term monitoring data. Programs addressing trends in breeding birds, amphibians, carbon dioxide, EPA’s program of monitoring and assessing water quality, and the NEON program all represent organized large scale efforts to acquire data to more fully understand system responses to stressors and hence make more informed resource management decisions. With all monitoring programs, however, funding is important to consider. Funding can be tenuous, especially when monitoring is long-term, and the individuals, agencies, or organizations responsible for the monitoring efforts often must spend considerable effort explaining the value of their monitoring programs to ensure that funding continues.

Whatever the impetus is for establishing a monitoring program, the objectives must be clear and specific, the questions treated as hypotheses and the data collected in a rigorous and unbiased manner to ensure that they are able to inform future decisions. The true importance of these steps will become clear after a plan is implemented and difficult questions arise, including when or if to make changes in the monitoring protocol, when monitoring should end, and at what point the data initiate a change in management actions. All of these decisions are best made by managers and stakeholders working together.

References

Anthony, R.G., E.D. Forsman, A.B. Franklin, D.R. Anderson, K.P. Burnham, G.C. White, C.J. Schwarz, J.D. Nichols, J.E. Hines, G.S. Olson, S.H. Ackers, L.S. Andrews, B.L. Biswell, P.C. Carlson, L.V. Diller, K.M. Dugger, K.E. Fehring, T.L. Fleming, R.P. Gerhardt, S.A. Gremel, R.J. Gutierrez, P.J. Happe, D.R. Herter, J.M. Higley, R.B. Horn, L.L. Irwin, P.J. Loschl, J.A. Reid, and S.G. Sovern. 2004. Status and trends in demography of northern spotted owls, 1985–2003. Final Report to the Regional Interagency Executive Committee, Portland, Oregon, USA.

Beeton, R.J.S., K.I. Buckley, G.J. Jones, D. Morgan, R.E. Reichelt, and T.E. Dennis. 2006. Independent report to the Australian Government Minister for the Environment and Heritage. Australian State of the Environment Committee, Canberra.

Cody, M.L., ed. 1985. Habitat selection in birds. Academic Press. Orlando, Florida. 558p.

Czech, B. 2006. If Rome is burning, why are we fiddling? Conserv Biol 20:1563–1565.

Dwyer, W.L. 1994. Seattle Audubon Society, et al. v. James Lyons, Assistant Secretary of Agriculture, et al. Order on motions for Summary Judgment RE 1994 Forest Plan Seattle, WA: U.S. District Court, Western District of Washington.

Environment Canada. 1996. State of the Environment Report Yukon. Environment Canada, Whitehorse, Yukon.

Government Accounting Office and National Academy of Science. 2007. Highlights of a forum: Measuring our nation’s natural resources and environmental sustainability. U.S. Government Printing Office Publication number GAO-08-127SP. Washington, DC.

Guarderas, A.P., S.D. Hacker, and J. Lubchenco. 2008. Current status of marine protected Areas in Latin America and the Caribbean. Conservation Biology. 22:1630-1640.

Haynes, R. W., B.T. Bormann, D.C. Lee, and J. R. Martin, Jon R., tech. eds. 2006.

Northwest Forest Plan—the first 10 years (1994-2003): synthesis of monitoring and research results. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW-GTR-651. Portland, OR: 292pp.

Heinz Center. 2002. The State of the Nation’s Ecosystems: Measuring the Lands, Waters, and Living Resources of the United States. Cambridge Univ. Press, New York.

Lint, J. 2001. Northern spotted owl effectiveness monitoring plan under the Northwest Forest Plan: Annual summary report 2000. Northwest Forest Plan Interagency Monitoring Program, Regional Ecosystem Office, Portland, OR.

Lint, J. tech. coord. 2005. Northwest Forest Plan—the first 10 years (1994–2003): status and trends of northern spotted owl populations and habitat. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW-GTR-648. Portland, OR. 176pp.

McComb, B.C. 2007. Wildlife habitat management: Concepts and applications in forestry. Taylor and Francis Publishers, CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL. 319pp.

McComb, W.C., S.A. Bonney, R.M. Sheffield, and N.D. Cost. 1986. Snag resources in Florida — are they sufficient for average populations of cavity nesters? Wildl. Soc. Bull. 14: 40-48.

Ottke, C., P. Kristensen, D. Maddox, and E. Rodenburg. 2000. Monitoring for impacts- Lessons on natural resources monitoring from 13 NGOs. Vol. I and II. World Resources Institute and Conservation International. Washington, D.C.

Sauer, J.R., J.E. Hines, and J. Fallon. 2007. The North American Breeding Bird Survey, Results and Analysis 1966 – 2006. Version 10.13.2007. U.S. Geological Survey Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, Laurel, MD

Schroeder, R.L. 2006. A system to evaluate the scientific quality of biological and restoration objectives using National Wildlife Refuge Comprehensive Conservation Plans as a case study. Journal for Nature Conservation. 14(3-4): 200-206.

Sheffield, R.M., N.D. Cost, W.A. Bechtold, and J.P. McClure. 1985. Pine growth reductions in the Southeast. Resource Bull. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, SE-83. 112pp.

Songorwa, A.N. 1999. Community based wildlife management (CWM) in Tanzania: Are the communities interested? World Development 27(12):2061- 2079.

Spies, T.A., K.N. Johnson, K.M. Burnett, J.L. Ohmann, B.C. McComb, G.H Reeves, P. Bettinger, J.D. Kline, and B. Garber-Yonts. 2007. Cumulative ecological and socioeconomic effects of forest policies in coastal Oregon. Ecological Applications. 17:5-17.

U.S Department of Agriculture, Forest Service; U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management [USDA USDI]. 1994. Final supplemental environmental impact statement on management of habitat for late-successional and old-growth forest related species within the range of the northern spotted owl. Volumes 1-2 and Record of Decision. US Government Printing Office, Washington, DC.

Walters, C. 1986. Adaptive management of renewable resources. Macmillan, New York.

Walters, C. J., and C.S. Holling. 1990. Large-scale management experiments and learning by doing. Ecology 71: 2060-2068.