19 Command Line Interfacing

While Python is a great language for stand-alone programming, it’s also a first-class language for interfacing with the Unix/Linux command line. This chapter explores some of those concepts, allowing us to use Python as “glue” to connect other powerful command line concepts.

Standard Input is a File Handle

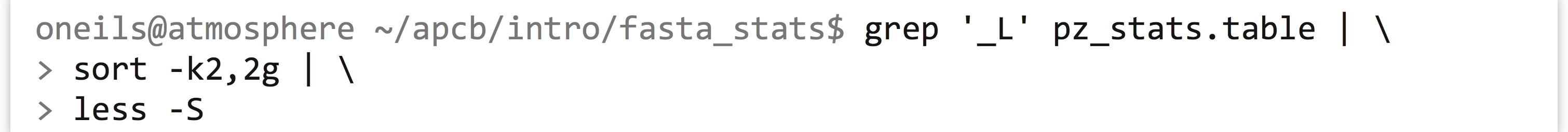

In previous chapters, we saw that simple Unix/Linux utilities such as grep and sort can be chained together for a variety of data manipulation tasks.

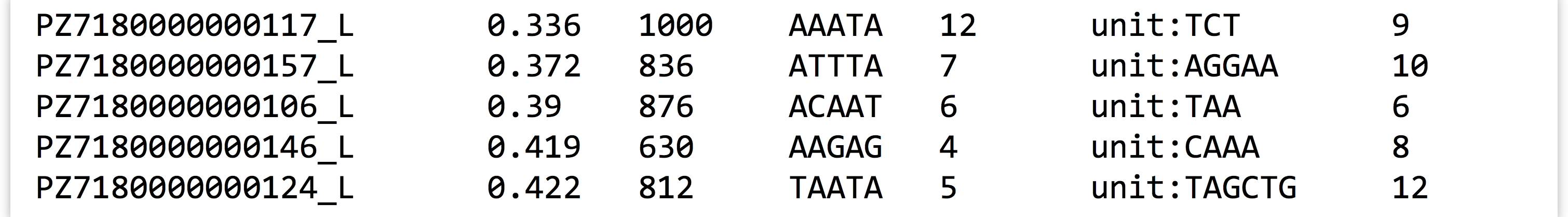

The above command uses grep to match lines in the file pz_stats.table against the pattern _L, which are printed to standard output. Using the | redirect, we send this output to sort on its standard input and sort the lines on the second column in general numeric order, before piping this output to less -S.

Again, sort and less are not reading their input from a file, but rather from standard input streams. Similarly, they are not writing their output to a file, but just printing to the standard output streams. It’s often useful to design our own small utilities as Python programs that operate in the same way.

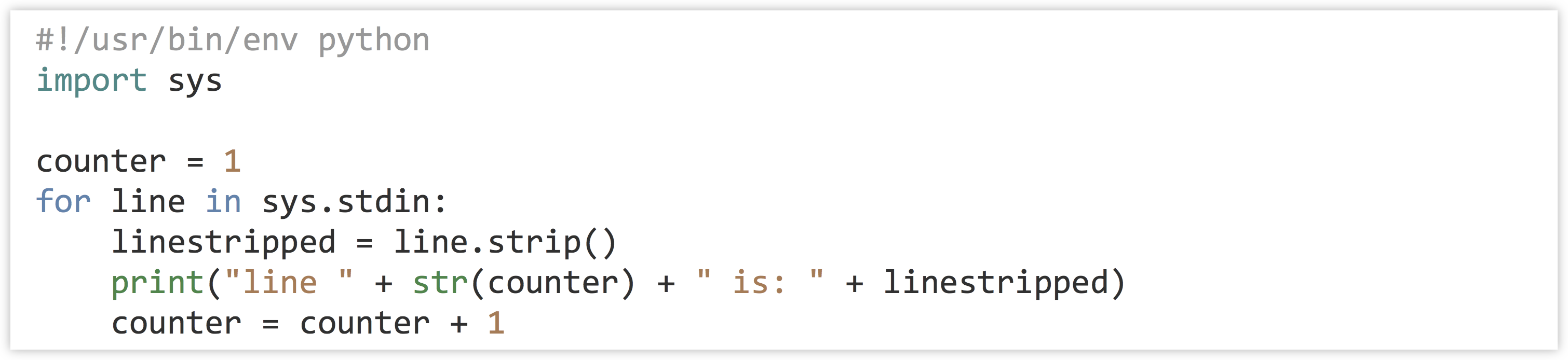

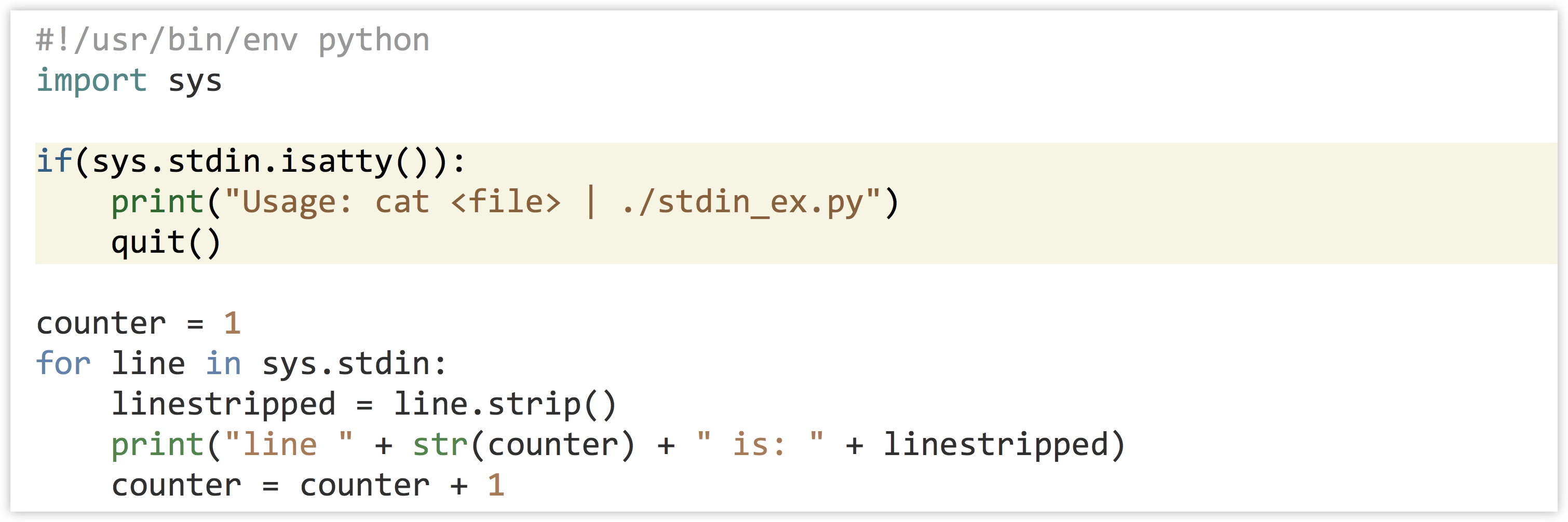

The “file handle as a pipe” analogy that we’ve been using will serve us well when writing programs that read input from standard input. The file handle associated with standard input is easy to use in Python. We just have to import the sys module, and then sys.stdin is a variable that references the read-only file handle that works just like any other. We don’t even have to use io.open(). Here’s a program that prints each line passed into it on standard input.

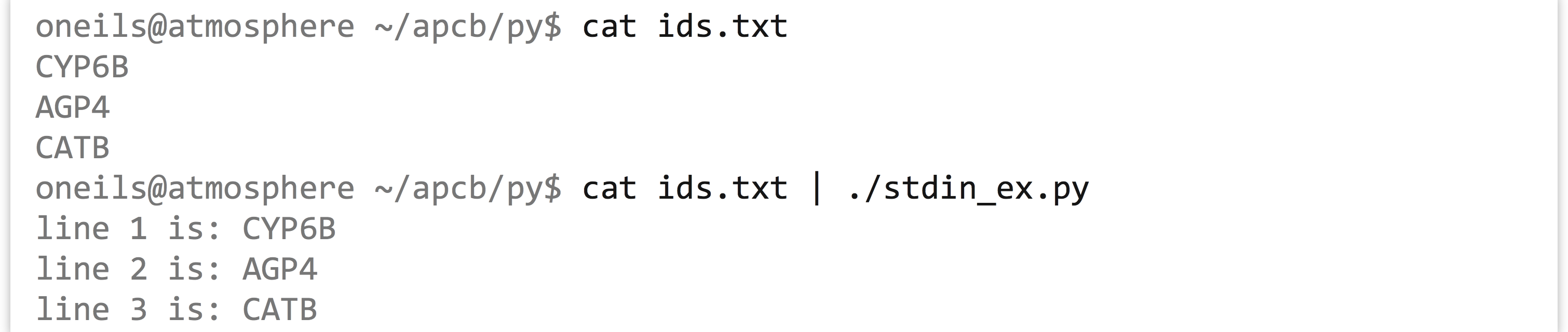

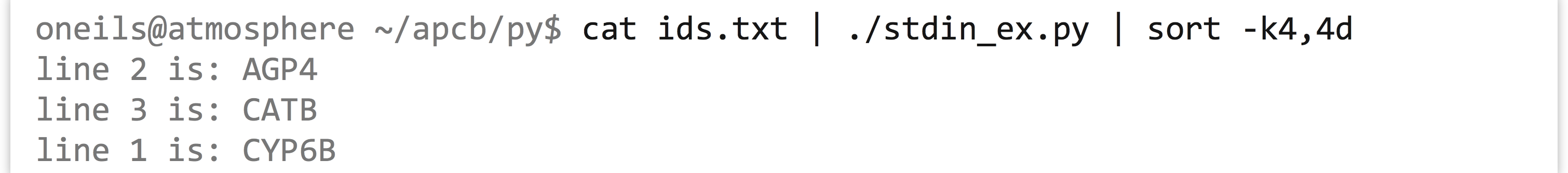

In this case, we’re using sys.stdin much like the read-only file handles we saw in previous examples. We can test our program on a simple file holding some gene IDs:

But if we attempt to run our program without giving it any input on the standard input stream, it will sit and wait for data that will never come.

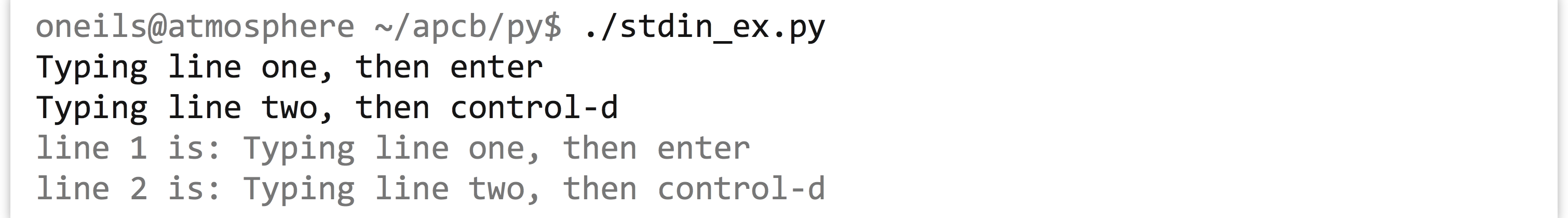

To kill the program, we can use the usual Control-c. The reason for this behavior is that the standard input stream can be used for input from standard out of another program (as we wish to do), or it can be used to build interactive programs. To see this, we can run the same program, except this time we’ll type some input using the keyboard, and when we’re done we’ll send the control code Control-d, which is a way to tell Python we are done sending input.

This hints at some interesting possibilities for interactive programs,[1] but in this case it would likely be confusing for someone wanting to utilize our program by piping data to it. Fortunately, sys.stdin has a method called .isatty() that returns True if there are no data present on the input stream when it is called. (TTY is short for “TeleTYpewriter,” a common name for a keyboard-connected input device of decades past.) So, we can fairly easily modify our program to quit with some helpful usage text if it detects that there are no data present on standard input.

It’s almost always a good idea for a program to check whether it is being called correctly, and to give some helpful usage information if not. It’s also common to include, in comments near the top of the program, authoring information such as date of last update and contact information. You may also need or want to include some copyright and licensing text, either of your own choice or your institution’s.

Note that we haven’t called .close() on the standard input file handle. Although Python won’t complain if you do, it is not required, as standard input is a special type of file handle that the operating system handles automatically.

Standard Output as a File Handle

Anything printed by a Python program is printed to the standard output stream, and so this output can also be sent to other programs for processing.

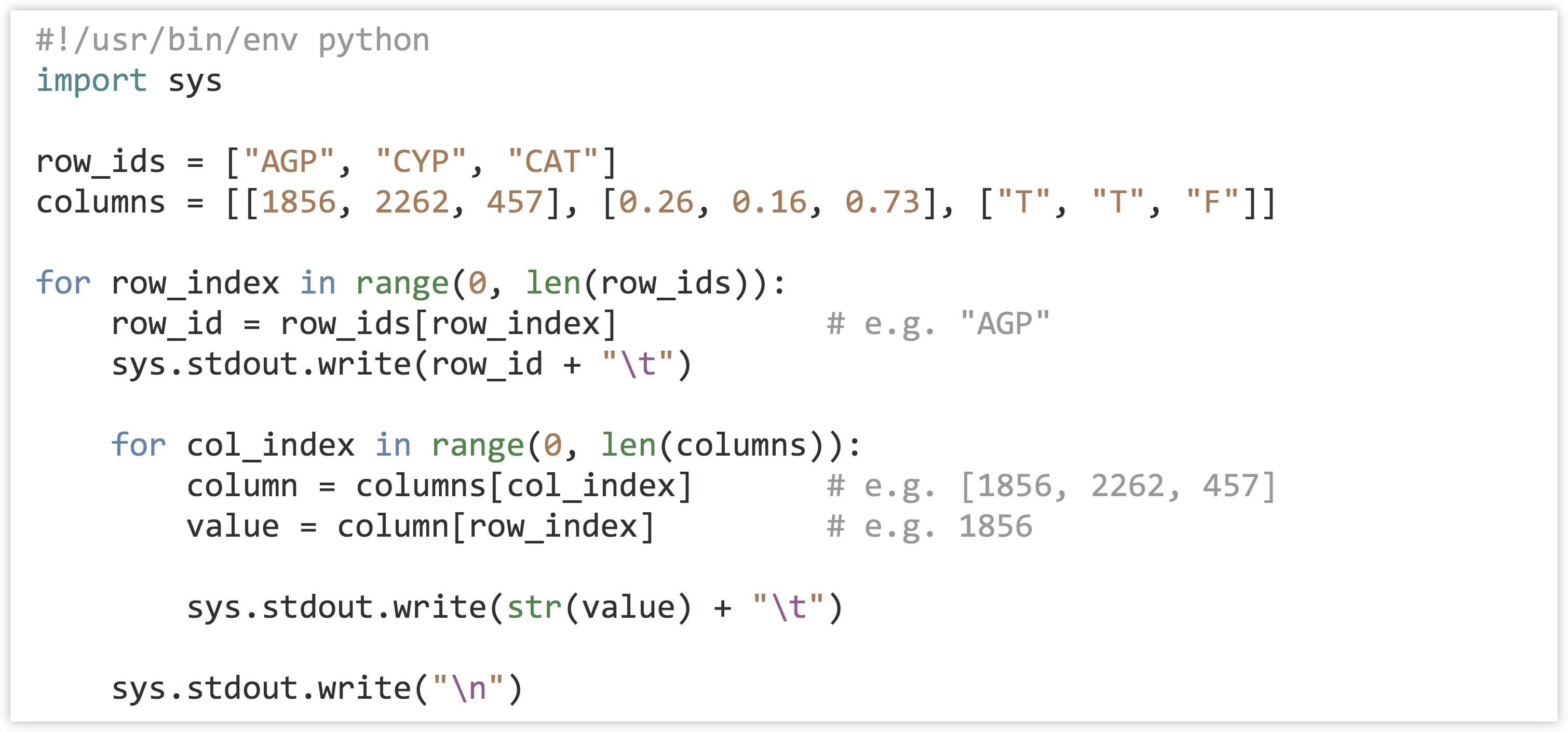

However, the sys module also provides access to the standard output file handle, sys.stdout. Just like other output-oriented file handles, we can call .write() on this file handle to print. The main difference between this method and calling print() is that while print() by default adds a "\n" newline character sys.stdout.write() does not.[2] This feature can be particularly useful when we wish to print a table in an element-by-element fashion because the data are not stored in strings representing individual rows.

Output from the above:

While print() is a simple way to print a line of text, sys.stdout.write() gives you more control over the formatting of printed output. As with sys.stdin, there is no need to call .close() on the file handle. Unlike other output-oriented file handles, data are regularly flushed from the pipe (either for printing or to another program’s standard input).

Command Line Parameters

So far, even though we’ve been executing our programs from the command line, none of our Python programs have accepted input parameters. Consider the example from chapter 18, “Python Functions,” where we computed the GC content for each sequence in a file. Rather than hard-coding the file name into the io.open() call, it would be preferable to supply the file name to work with on the command line, as in ./ids_seqs_gcs.py ids_seqs.txt.

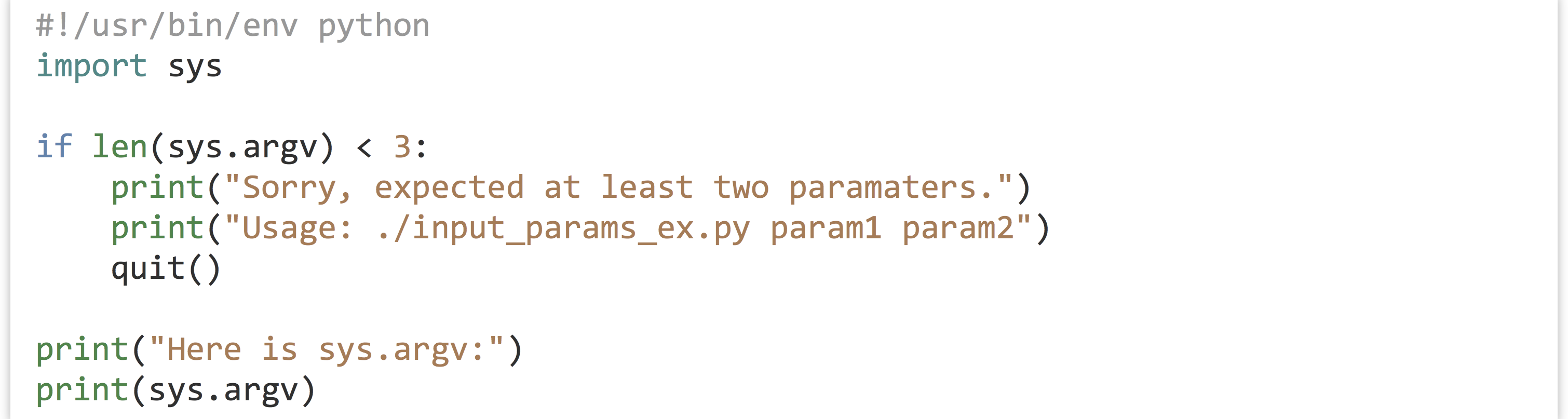

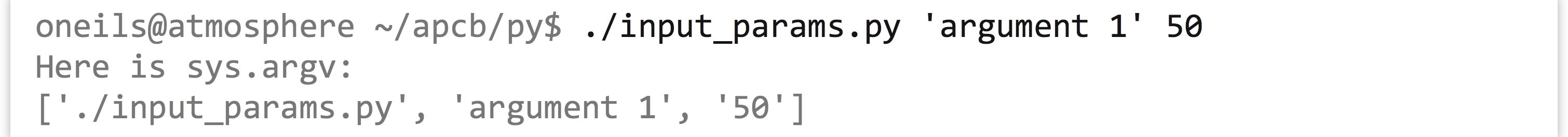

The sys module again comes to the rescue. After importing sys, the variable sys.argv references a list of strings that contain, starting at index 0, the name of the script itself, then each parameter. Because sys.argv is always a list of strings, if we want to input a float or integer argument, we’ll need to convert the appropriate parameter using int() or float() before use.

This code also determines whether the expected number of parameters has been given by the user by looking at len(sys.argv), exiting if this isn’t the case.

As with other programs run on the command line, if we wish to send a single parameter that contains spaces, we need to wrap it in single or double quotes.

Although we won’t cover it here, the argparse module makes writing scripts that require input parameters of different types relatively easy. The argparse module also automates the printing and formatting of help information that can be accessed by users who run the program with a -h or --help flag. A variety of tutorials for argparse can be found online. (There is also a simpler, but less featureful, module optparse.)

Executing Shell Commands within Python

It is sometimes useful to execute other programs from within our own programs. This could be because we want to execute an algorithmically generated series of commands (e.g., perhaps we want to run a genome assembly program on a variety of files in sequence), or perhaps we want to get the output of a program run on the command line.

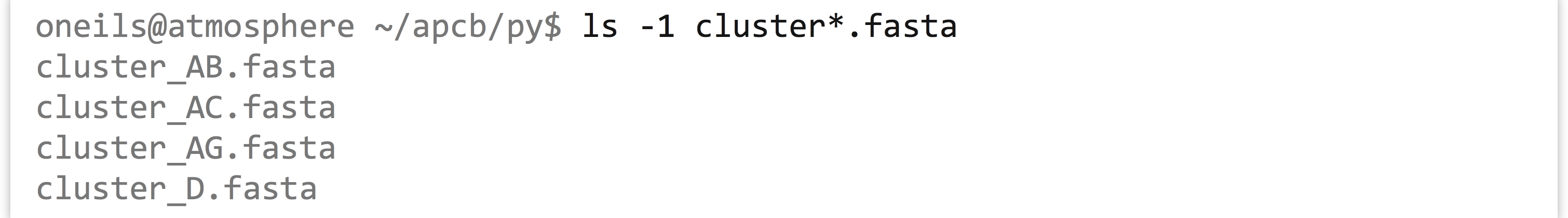

Consider the command line task of listing all of the files in the current directory matching the pattern cluster*.fasta. For this we can use ls -1 cluster*.fasta, where -1 tells ls to print its output as a single column of file names, and cluster*.fasta matches all file names matching the desired pattern (like cluster_AB.fasta, cluster_AC.fasta, cluster_AG.fasta, and cluster_D.fasta.).

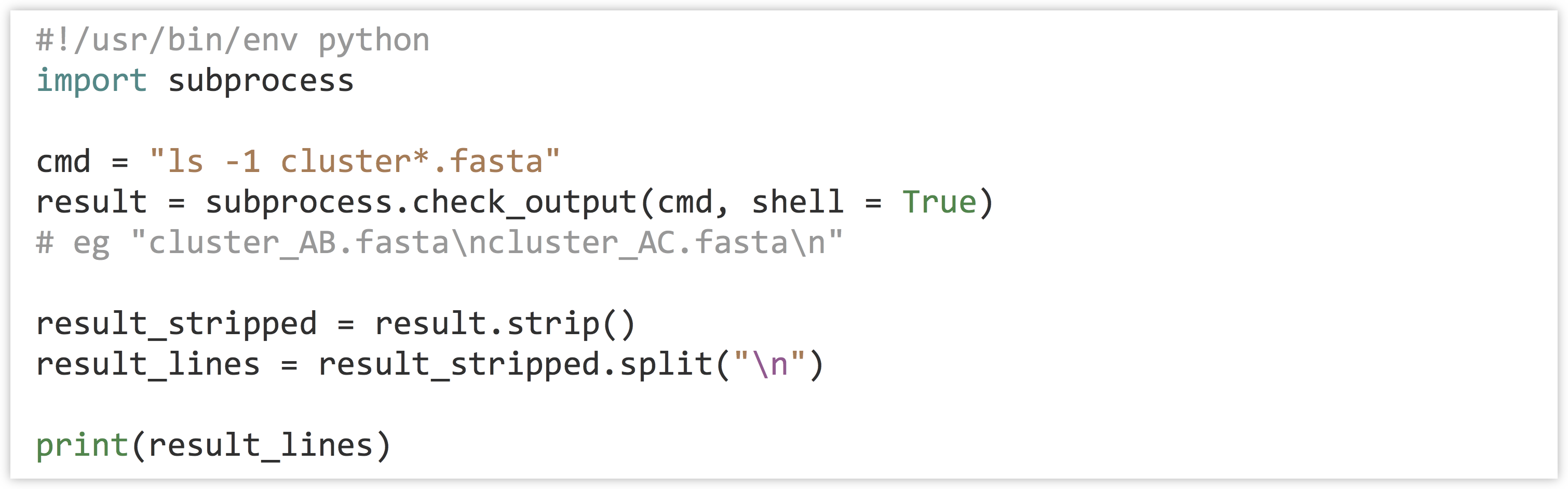

There are a few ways to get this information in a Python program, but one of the easiest is to run the ls -1 cluster*.fasta command from within our program, capturing the result as a string.[3] The subprocess module allows us to do exactly this by using the subprocess.check_output() function. This function takes a number of potential parameters, but we’ll run it with just two: (1) the command we wish to execute (as a string) and (2) shell = True, which indicates that the Python interpreter should run the command as though we had run it on the command line.

The result of the function call is a single string containing whatever the command printed to standard output. Because it’s a single string, if we want it represented as a list of lines, we need to first .strip() off any newline characters at the end, and then split it on the \n characters that separate the lines.

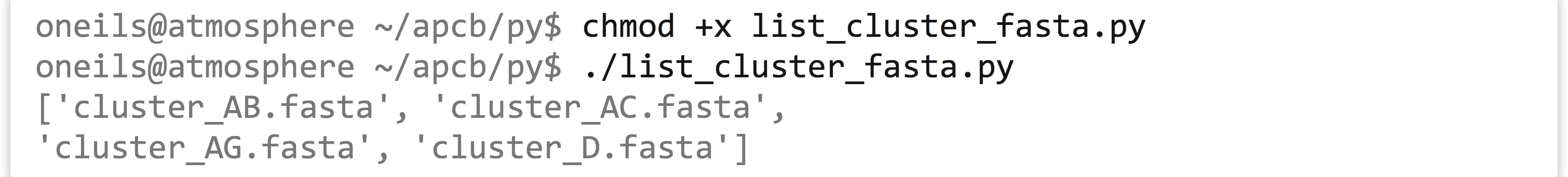

Running the program, we see that the result is a list of strings, one per file:

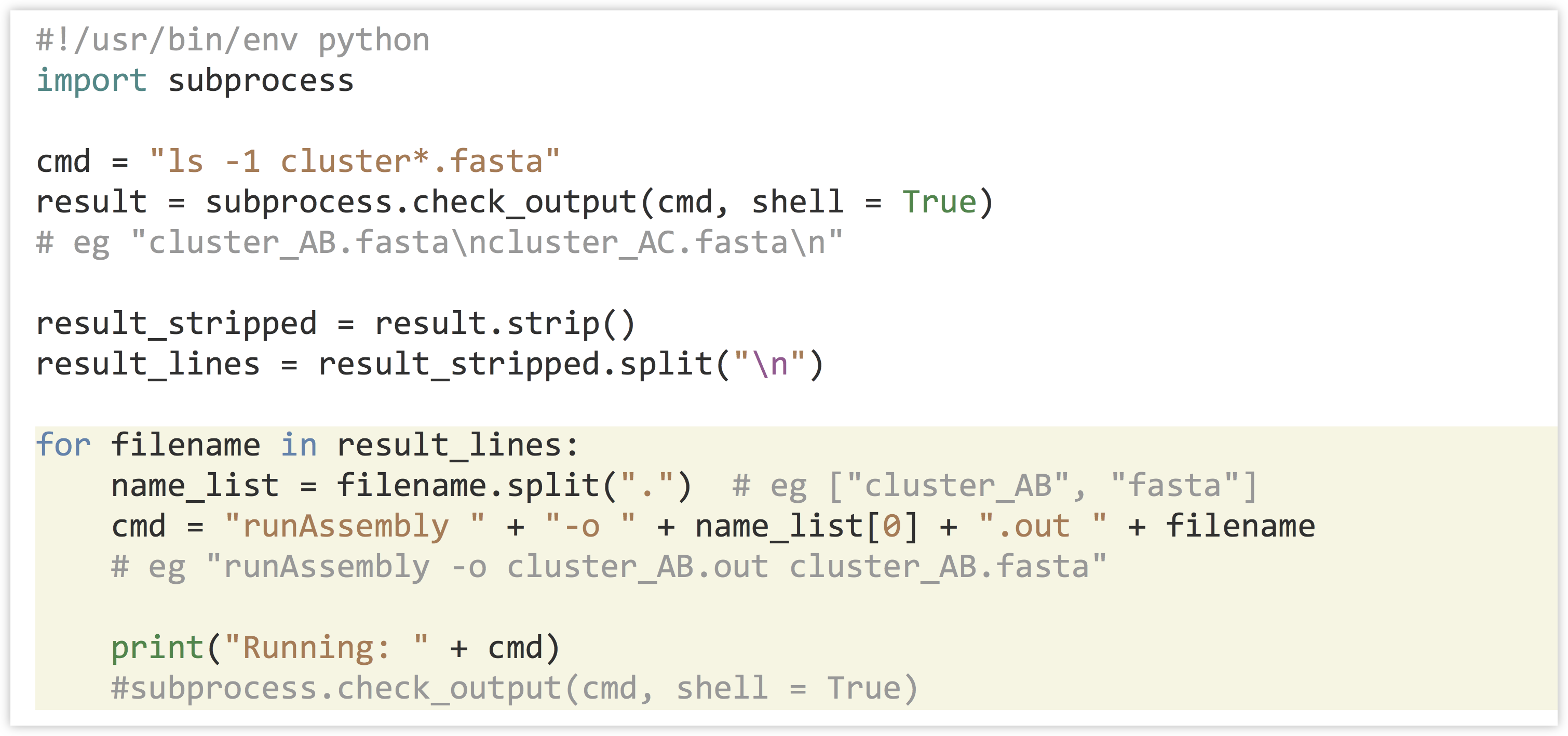

With this list of file names in hand, we might wish to run a series of assemblies with the program runAssembly (produced by 454 Life Sciences for assembling transcript sequences). This program requires a -o parameter to specify where outputs should be written as well as a file name input; we generate these with string operations to “build” a command to execute. Once we are satisfied with the commands, we can uncomment the actual call to subprocess.check_output().

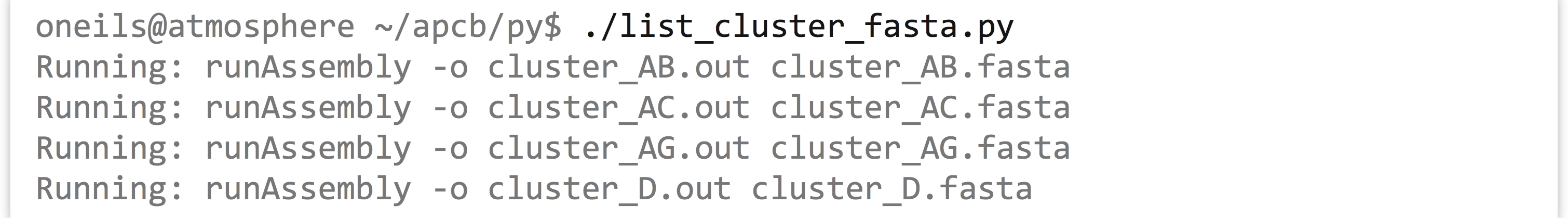

This version of the program reports the commands that will be run.[4]

While a command is running via the subprocess.check_output() function in this way, the program will wait before continuing to the next line (though you’ll likely only notice if the command takes a long time to execute). If the command crashes or is killed, the Python program will crash with a CalledProcessError too (usually a good thing!).

Other functions in the subprocess module allow for running commands in the background—so the script doesn’t wait for them to complete before continuing in its own execution—and to work with multiple such processes while communicating with them. Other Python modules even allow for advanced work with parallel execution and threading, though these topics are beyond the scope of this chapter.

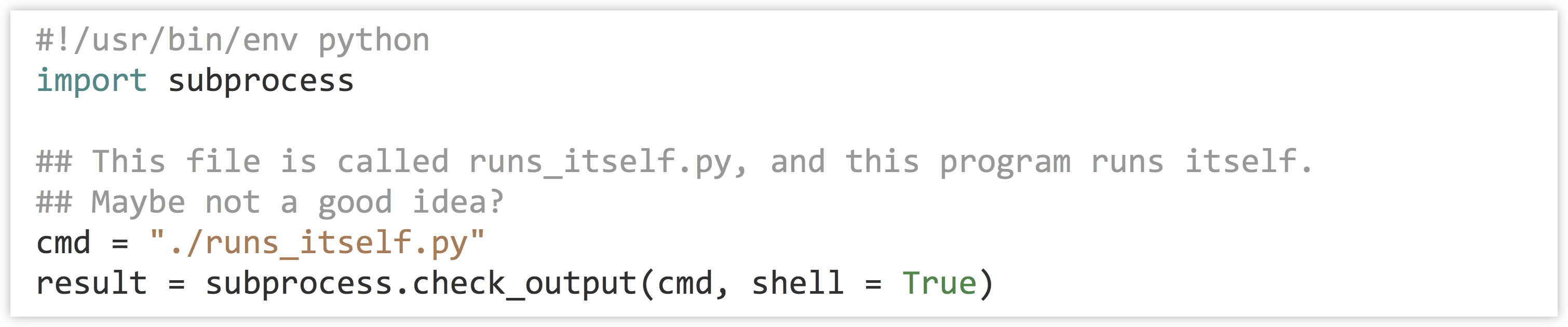

Don’t forget that you are responsible for the execution of your programs! If you write a program that executes many other programs, you can quickly utilize more computational resources than you realize. If you are working on a system that you don’t mind taking some risks with, you could try to run the following program, which executes a copy of itself (which in turn executes a copy of itself, which in turn executes a copy of itself, and on and on):

Exercises

- The table-printing example used

sys.stdoutto nicely print a table in column-major order. Write a function calledprint_row_major()that prints a table stored in row-major order, so a call likeprint_row_major([["A", "B"], ["C", "D"], ["E", "F"]])results in output looking like:

- Write a program called

stdin_eval_mean.pythat reads a file in the format ofpz_blastx_yeast_top1.txtonsys.stdin, computes the mean of the E-value column (column 11, with values like1e-32), and prints the mean to standard output. If there are no data on standard input, the program should produce a “usage” message.Next, try running the program with

cat pz_blastx_yeast_top1.txt | ./stdin_eval_mean.py. Also, try prefiltering the lines before the computation with something likecat pz_blastx_yeast_top1.txt | grep '_L' | ./stdin_eval_mean.py.Now copy this program to one called

stdin_eval_sd.pythat reads inpz_blastx_yeast_top1.txtonsys.stdinand computes and prints the standard deviation of the E values. Again, try running the program with and without prefiltering withgrep. (At this point you should be comfortable with writingmean()andsd()functions that take lists of floats and return answers. Yoursd()function might well call themean()function.) - Modify the

stdin_eval_mean.pyprogram above (call the new versionstdin_eval_mean_threshold.py) to accept an E-value upper threshold as a first parameter. Thuscat pz_blastx_yeast_top1.txt | ./stdin_eval_mean.py 1e-6should compute and print the mean of the E-value column, but only for those lines whose E value is less than 1e-6. (You’ll need to usesys.argvand be sure to convert the entry therein to a float.)Your program should print usage information and exit if either there are no data provided on standard input, or if there is no threshold argument.

- Try using a line of code like

value = input("What is your name? ")followed byprint(value). Note that when running the program and prompted, you’ll need to include quotes when typing your name (e.g.,"Shawn"). ↵ - In Python 3.0 and above, the

print()function can also take some parameters to specify whether the"\n"should be printed or not, or even be replaced by some other character. ↵ - An alternative method to get a list of files is to use the

osmodule and theos.listdir()function, which will return a list of file names. For listing and working with file names and paths, the functions in theosmodule are are preferred, because they will work whether the program is run on a Windows system or a Unix-like system.For running shell commands more generally, thesubprocessmodule is useful. Here we’re illustrating that on the Unix/Linux command line, it can do both jobs by calling out to system utilities. ↵ - Here we are splitting filenames into a [name, extension] list with

filename.split("."). This method won't work if there are multiple.s in the file. A more robust alternative is found in theosmodule:os.path.splitext("this.file.txt")would return["this.file", "txt"]. ↵