Organizational Control

Up to this point you should have become familiar with the planning, organizing, and leading components of the P-O-L-C framework. This section addresses the controlling component, often taking the form of internal systems and process, to complete your understanding of P-O-L-C. As you know, planning comprises all the activities associated with the formulation of your strategy, including the establishment of near- and long-term goals and objectives. Organizing and leading are the choices made about the way people work together and are motivated to achieve individual and group goals and objectives.

What Is Organizational Control?

The fourth facet of P-O-L-C, organizational control, refers to the process by which an organization influences its subunits and members to behave in ways that lead to the attainment of organizational goals and objectives. When properly designed, such controls should lead to better performance because an organization is able to execute its strategy better.[1] As shown in the P-O-L-C framework figure (Unit 1), we typically think of or talk about control in a sequential sense, where controls (systems and processes) are put in place to make sure everything is on track and stays on track. Controls can be as simple as a checklist, such as that used by pilots, flight crews, and some doctors. Increasingly, however, organizations manage the various levels, types, and forms of control through systems called Balanced Scorecards. We will discuss these in detail later in the unit.

Example 4.10 Balanced Scorecard

Jeff Nock, a marketing and product development specialist, discusses the importance of using a balanced scorecard within a business. Nock has a history of helping grow businesses, and his research has indicated the importance of using this tool. In last year’s 2GC Active Management’s survey, over 50% of the respondents reported using a balanced scorecard for strategy implementation as well as operational management.

Source: Yahoo, Jeff Nock Reveals the Importance of Using a Business Scorecard, 2020Wi

Organizational control typically involves four steps: (1) establish standards, (2) measure performance, (3) compare performance to standards, and then (4) take corrective action as needed. Corrective action can include changes made to the performance standards—setting them higher or lower or identifying new or additional standards. Sometimes we think of organizational controls only when they seem to be absent, as in the 2008 meltdown of U.S. financial markets, the crisis in the U.S. auto industry, or the much earlier demise of Enron and MCI/WorldCom due to fraud and inadequate controls. However, as shown in the P-O-L-C Framework in Unit 1, good controls are relevant to a large spectrum of firms beyond Wall Street and big industry.

The Costs and Benefits of Organizational Controls

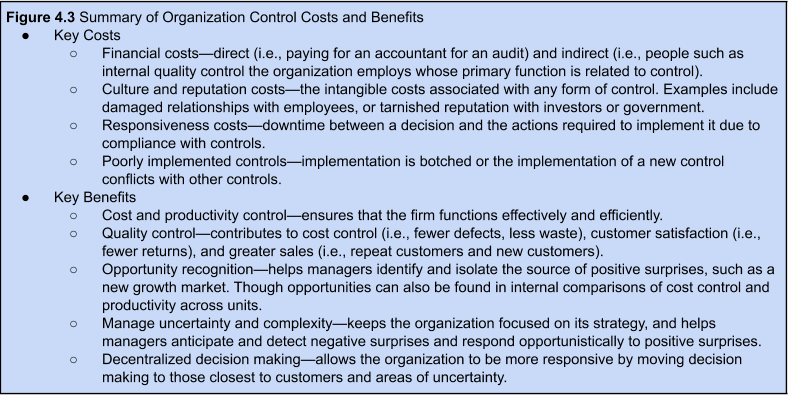

Organizational controls provide significant benefits, particularly when they help the firm stay on track with respect to its strategy. External stakeholders, too, such as government, investors, and public interest groups have an interest in seeing certain types or levels of control are in place. However, controls also come at a cost. It is useful to know that there are trade-offs between having and not having organizational controls, and even among the different forms of control. Let’s look at some of the predominant costs and benefits of organizational controls, which are summarized in the following figure.

Example 4.11 Costs of Organizational Controls

The importance of having organizational controls in place is apparent as the Boy Scouts of America file for bankruptcy in 2020. This is in response to numerous unsettled pending lawsuits and the agency’s inability to address those adequately. The Scouts are hoping by filing for bankruptcy protection, and they will be able to move forward unencumbered. The BSA admitted its mistakes, put new structure and controls in place, are working to help the individuals who were affected, and hope to move forward in a more transparent fashion that will keep them relevant in the 21st Century.

Source: NBC News, Boy Scouts bankruptcy is good news for victims, the organization and hopefully, America, 2020Wi

Costs

Controls can cost the organization in several areas, including (1) financial, (2) damage to culture and reputation, (3) decreased responsiveness, and (4) botched implementation. An example of financial cost is the fact that organizations are often required to perform and report the results of a financial audit. These audits are typically undertaken by external accounting firms, which charge a substantial fee for their services; the auditor may be a large firm like Accenture or KPMG, or a smaller local accounting office. Such audits are a way for banks, investors, and other key stakeholders to understand how financially fit the organization is. Thus, if an organization needs to borrow money from banks or has investors, it can only obtain these benefits if it incurs the monetary and staffing costs of the financial audit.

Example 4.12 Organizational Control Gone Wrong

Multiple organizational design blunders affected companies’ productivity and organizational dynamic as a whole. The example that stuck out most to me was designing performance metrics and incentives for different branches and divisions of a company. If these metrics are misaligned, they can encourage rivalry between the various divisions and discourage collaboration that will improve cohesion within the company.

Source: Harvard Business Review: 4 Organizational Design Issues That Most Leaders Misdiagnose, 2020Wi

Controls also can have costs in terms of organization culture and reputation. While you can imagine that organizations might want to keep track of employee behavior, or otherwise put forms of strict monitoring in place, these efforts can have undesirable cultural consequences in the form of reduced employee loyalty, greater turnover, or damage to the organization’s external reputation. Management researchers such as the late London Business School professor Sumantra Ghoshal have criticized theories that focus on the economic aspects of man (i.e., assumes that individuals are always opportunistic). According to Ghoshal, “A theory that assumes that managers cannot be relied upon by shareholders can make managers less reliable.”[2] Such theory, he warned, would become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

The third potential cost of having controls is that they can afford less organizational flexibility and responsiveness. Typically, controls are put in place to prevent problems, but controls can also create problems. For instance, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) is responsible for helping people and business cope with the consequences of natural disasters, such as hurricanes. After Hurricane Katrina devastated communities along the U.S. Gulf Coast in 2005, FEMA found that it could not provide prompt relief to the hurricane victims because of the many levels of financial controls that it had in place.[3]

The fourth area of cost, botched implementation, may seem obvious, but it is more common than you might think (or than managers might hope). Sometimes the controls are just poorly understood, so that their launch creates significant unintended, negative consequences. For example, when Hershey Foods put a new computer-based control system in place in 1999, there were so many problems with its installation that it was not able to fulfill a large percentage of its Halloween season chocolate sales that year. It did finally get the controls in working order, but the downtime created huge costs for the company in terms of inefficiencies and lost sales.[4] Some added controls may also interfere with others. For instance, a new quality control system may improve product performance but also delay product deliveries to customers.

Benefits

Although organizational controls come at some cost, most controls are valid and valuable management tools. When they are well designed and implemented, they provide at least five possible areas of benefits, including (1) improved cost and productivity control, (2) improved quality control, (3) opportunity recognition, (4) better ability to manage uncertainty and complexity, and (5) better ability to decentralize decision making. Let’s look at each one of these benefits in turn.

First, good controls help the organization to be efficient and effective by helping managers to control costs and productivity levels. Cost can be controlled using budgets, where managers compare actual expenses to forecasted ones. Similarly, productivity can be controlled by comparing how much each person can produce, in terms of service or products. For instance, you can imagine that the productivity of a fast-food restaurant like McDonald’s depends on the speed of its order takers and meal preparers. McDonald’s can look across all its restaurants to identify the target speed for taking an order or wrapping a burger, then measure each store’s performance on these dimensions.

Quality control is a second benefit of controls. Increasingly, quality can be quantified in terms of response time (i.e., How long did it take you to get that burger?) or accuracy (Did the burger weigh one-quarter pound?). Similarly, Toyota tracks the quality of its cars according to hundreds of quantified dimensions, including the number of defects per car. Some measures of quality are qualitative, however. For instance, Toyota also tries to gauge how “delighted” each customer is with its vehicles and dealer service. You also may be familiar with quality control through the Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Program Award. The Baldrige award is given by the president of the United States to businesses—manufacturing and service, small and large—and to education, healthcare, and nonprofit organizations that apply and are judged to be outstanding in seven areas: leadership; strategic planning; customer and market focus; measurement, analysis, and knowledge management; human resource focus; process management; and results. Controlling—how well the organization measures and analyzes its processes—is a key criterion for winning the award. The Baldrige award is given to organizations in a wide range of categories and industries, from education to ethics to manufacturing.

The third area by which organizations can benefit from controls is opportunity recognition. Opportunities can come from outside of the organization and typically are the result of a surprise. For instance, when Nestlé purchased the Carnation Company for its ice cream business, it had also planned to sell off Carnation’s pet food line of products. However, through its financial controls, Nestlé found that the pet food business was even more profitable than the ice cream, and kept both. Opportunities can come from inside the organization too, as would be the case if McDonald’s finds that one of its restaurants is exceptionally good at managing costs or productivity. It can then take this learned ability and transfer it to other restaurants through training and other means.

Example 4.13 Effective Organizational Controls

Google has implemented an effective organizational structure that focuses on flatness in order to be innovative. Their matrix structure and the organizational culture that it supports emphasizes change and direct social links within the firm. These elements of structure and culture support the firm’s strategic interest for excellence in innovation and are in support of Google’s corporate mission and vision.

Source: Panmore Institute, Nathaniel Smithson, Google’s Organizational Structure & Organizational Culture (An Analysis), Siyuan Wang

Controls also help organizations manage uncertainty and complexity. This is a fourth area of benefit from well-designed and implemented controls. Perhaps the most easily understood example of this type of benefit is how financial controls help an organization navigate economic downturns. Without budgets and productivity controls in place, the organization might not know it has lost sales, or if expenses are out of control until it is too late.

The fifth area of benefit in organizational control is related to decentralized decision making. Organization researchers have long argued that performance is best when those people and areas of the organization that are closest to customers and pockets of uncertainty also have the ability (i.e., the information and authority) to respond to them.[5] Going back to our McDonald’s example, you can imagine that it would be hard to give a store manager information about her store’s performance and possible choices if information about performance were only compiled at the city, region, or corporate level. With store-level performance tracking (or, even better, tracking of performance by the hour within a store), McDonald’s gives store managers the information they need to respond to changes in local demand. Similarly, it equips McDonald’s to give those managers the authority to make local decisions, track that decision-making performance, and feed it back into the control and reward systems.

- Kuratko, D. F., Ireland, R. D., & Hornsby. J. S. (2001). Improving firm performance through entrepreneurial actions: Acordia’s corporate entrepreneurship strategy. Academy of Management Executive, 15(4), 60–71. ↵

- Ghoshal S., & Moran, P. (1996). Bad for practice: A critique of the transaction cost theory. Academy of Management Review. 21(1), 13–47. ↵

- U.S. Government Printing Office. (2006, February 15). Executive summary. Select Bipartisan Committee to Investigate the Preparation for and Response to Hurricane Katrina. ↵

- Retrieved January 30, 2009, from Hershey profits for 4Q 1999 down 11% due to SAP implementation problem. http://www.greenspun.com/bboard/q-and-a-fetch-msg.tcl?msg_id=002SUM ↵

- Galbraith, J. R. (1974). Organization design: An information processing view. Interfaces, 4, 28–36. Galbraith believes that “the greater the uncertainty of the task, the greater the amount of information that must be processed between decision makers during the execution of the task to get a given level of performance.” Firms can reduce uncertainty through better planning and coordination, often by rules, hierarchy, or goals. Galbraith states that “the critical limiting factor of an organizational form is the ability to handle the non-routine events that cannot be anticipated or planned for.” ↵