What Is Strategic Management?

Strategic management, strategy for short, is essentially about choice — in terms of what the organization will do and won’t do to achieve specific goals and objectives, where such goals and objectives lead to the realization of a stated mission and vision. Strategy is a central part of the planning function in P-O-L-C. Strategy is also about making choices that provide the organization with some measure of a sustainable competitive advantage. For the most part, this chapter emphasizes strategy formulation (answers to the “What should our strategy be?” question) as opposed to strategy implementation (answers to question “How do we execute our strategy?”). The central position of strategy is summarized in Figure 1.1.

| Planning | Organizing | Leading | Controlling |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Vision & Mission 2. Strategizing 3. Goals & Objectives |

1. Organization Design 2. Culture 3. Social Networks |

1. Leadership 2. Decision Making 3. Communications 4. Groups/Teams 5. Motivation |

1. Systems/Processes 2. Strategic Human Resources |

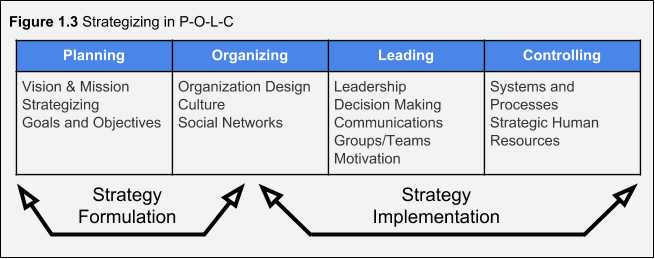

As you can see in Figure 1.1, the P-O-L-C framework starts with “planning”. Planning is related to, but not synonymous with, strategic management. The concept of strategic management reflects what a firm is doing to achieve its mission and vision as seen by its achievement of specific goals and objectives. A more formal definition tells us that strategic management “is the process by which a firm manages the formulation and implementation of its strategy.”[1]

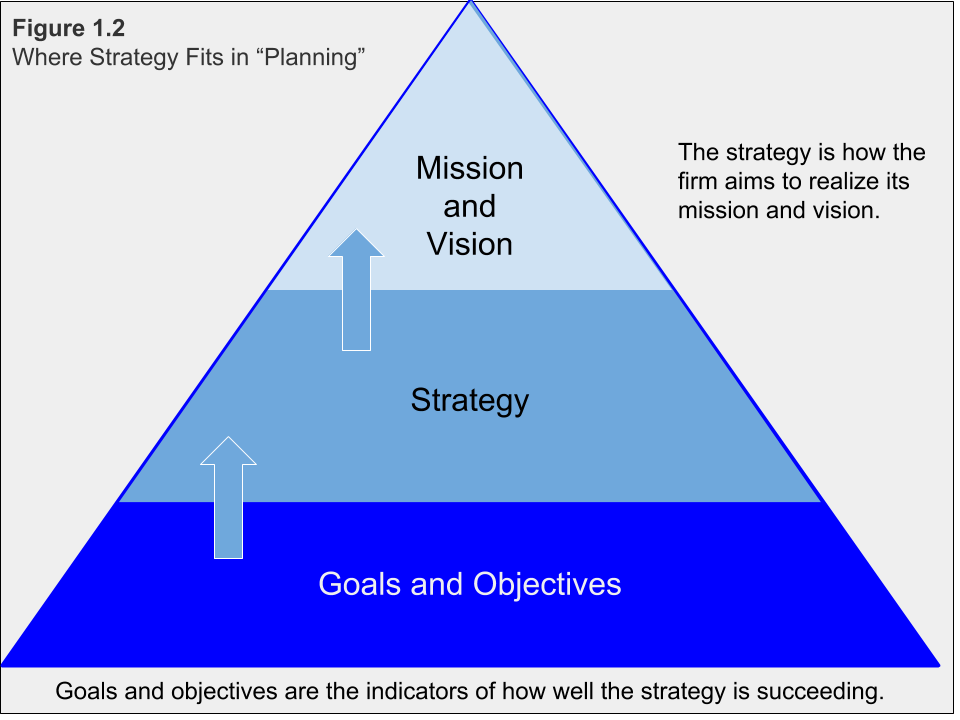

Using the definition of strategic management above then, the strategic management process is “the coordinated means by which an organization achieves its goals and objectives.”[2] Others have described strategy as the pattern of resource allocation choices and organizational arrangements that result from managerial decision making.[3] Planning activities that lead to the formulation of a strategy is sometimes called strategic planning. Strategy implementation then refers to the tasks and tactics managers must perform to put the desired strategy into action. See Figure 1.2 for a description of how strategy fits with planning.

The concept of strategy is relevant to all types of organizations, from large, public companies like GE, to religious organizations, political parties, and nonprofits.

Strategic Management in the P-O-L-C Framework

If vision and mission are the heart and soul of planning (in the P-O-L-C framework), then strategy, particularly strategy formulation, would be the brain. Figure 1.3 summarizes where strategy formulation (strategizing) and implementation fit in the planning and other components of P-O-L-C. We will focus primarily on the strategy formulation aspects of strategic management because implementation is essentially organizing, leading, and controlling P-O-L-C components. Unit 4: Internal Capabilities of this textbook will provide additional information regarding the implementation components (O-L-C).

You see that planning starts with vision and mission and concludes with setting goals and objectives. In between is the critical role played by strategy. Specifically, a strategy captures and communicates how vision and mission will be achieved and sets forth the goals and objectives needed to demonstrate that the organization is on the right path for achieving them. At this point, even in terms of strategy formulation, there are two aspects of strategizing that you should recognize. The first, corporate strategy answers strategy questions related to “What business or businesses should we be in?” and “How does business X help us compete in business Y, and vice versa?” In many ways, corporate strategy considers an organization to be a portfolio of businesses, resources, capabilities, or activities.

Example 1.1 – Synergy

Inspire Brands, the parent of companies such as Arby’s, Buffalo Wild Wings, Sonic, and Rusty Taco, recently acquired Jimmy John’s in an attempt to capitalize on the company’s strengths. The acquisition makes Inspire the fourth largest restaurant company in the US and the company plans on utilizing its long-term outlooks and innovative strategy to streamline Jimmy John’s into its portfolio of companies. The addition of Jimmy John’s comes as the company faces increasing competition from other sandwich shops and third-party delivery services like GrubHub and DoorDash. The hope is to incorporate Jimmy John’s inhouse delivery service with Inspire’s other restaurant strengths to establish Jimmy John’s dominance in the industry.

Source: CNBC, Arby’s owner Inspire Brands buys Jimmy John’s, Michael Creenen, 2019Fa

The logic behind corporate strategy is one of synergy and diversification. That is, synergies arise when each of YUM! Brands food outlets does better because they have common ownership and can share valuable inputs into their businesses. Specifically, synergy exists when the interaction of two or more activities (such as those in a business) create a combined effect greater than the sum of their individual effects. The idea is that the combination of certain businesses is stronger than those same businesses would be individually. Their coordination under a common owner allows them to either do things less expensively, or of a higher quality.

Example 1.2 – Concentric Diversification

The German software company, SAP, recently acquired the experience management software company, Qualtrics, after Qualtrics announced their IPO price range. SAP plans to implement Qualtrics’ cloud-based experience data into their own operational data software to diversify into the customer relationship management market so they may compete against companies like Salesforce.

Source: Forbes, SAP Acquires Cloud Unicorn Qualtrics For $8 Billion Just Before Its IPO, 2018Fa

Diversification, in contrast, is where an organization participates in multiple businesses that are in some way distinct from each other, as Taco Bell is from Pizza Hut, for instance. Just as with a portfolio of stock, the purpose of diversification is to spread out risk and opportunities over a larger set of businesses. Some may be high growth, some slow growth or declining; some may perform worse during recessions, while others perform better. There are three major diversification strategies: (1) concentric diversification, where the new business produces products that are technically similar to the company’s current product but that appeal to a new consumer group; (2) horizontal diversification, where the new business produces products that are totally unrelated to the company’s current product but that appeal to the same consumer group; and (3) conglomerate diversification, where the new business produces products that are totally unrelated to the company’s current product and that appeal to an entirely new consumer group.

Whereas corporate strategy looks at an organization as a portfolio of things, business strategy focuses on how a given business needs to compete to be effective. Again, all organizations need strategies to survive and thrive. A neighborhood church, for instance, probably wants to serve existing members, build new membership, and, at the same time, raise surplus monies to help it with outreach activities. Its strategy would answer questions surrounding the accomplishment of these key objectives. In a for-profit company such as McDonald’s, its business strategy would help it keep existing customers, expanding its business by moving into new markets, and taking customers from competitors like Taco Bell and Burger King, all while maintaining a profit level demanded by the stock market.

Strategic Inputs

So what are the inputs into strategizing? At the most basic level, you will need to gather information and conduct analysis about the internal characteristics of the organization and the external market conditions. This means both an internal and an external appraisal. On the internal side, you will want to gain a sense of the organization’s strengths and weaknesses; on the external side, develop a sense of the organization’s opportunities and threats. Together, these four inputs into strategizing (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats) are referred to as SWOT analysis. It doesn’t matter if you start this appraisal internally or externally, but you will quickly see the two perspectives need to mesh eventually.

Example 1.3 Sustainable Advantage

Walmart’s supply chain management strategy has given them multiple sustainable competitive advantages that include lower product costs, reduced inventory carrying costs, competitive pricing and a large variety in-store products. All of these advantages are hard to duplicate at the scale Walmart is currently at as well as provide a favorable long term position over their competitors.

Source: TradeGecko, Walmart’s successful supply chain management, 2018Fa

Strengths and Weaknesses

A good starting point for strategizing is an assessment of what an organization does well and what it doesn’t do well. In general good strategies take advantage of strengths and minimize the disadvantages posed by any weaknesses. Michael Jordan, for instance, is an excellent all-around athlete; he excels in baseball and golf, but his athletic skills show best in basketball. As with Jordan, when you can identify certain strengths that set an organization well apart from actual and potential competitors, that strength is considered a source of competitive advantage. The hardest thing for an organization to do is to develop its competitive advantage into a sustainable competitive advantage. This means the organization’s strengths cannot be easily duplicated or imitated by other firms, nor made redundant or less valuable by changes in the external environment.

Opportunities and Threats

On the basis of what you just learned about competitive advantage and sustainable competitive advantage, you can see why some understanding of the external environment is a critical input into strategy. Opportunities assess the external attractive factors that represent the reason for a business to exist and prosper. These are external to the business. What opportunities exist in its market, or in the environment, from which managers might hope the organization will benefit? Threats include factors beyond your control that could place the strategy, or the business, at risk. These are also external—managers typically have no control over them, but may benefit by having contingency plans to address them if they occur.

In a nutshell, SWOT analysis helps you identify strategic alternatives that address the following questions:

- Strengths and Opportunities (SO)—How can you use your strengths to take advantage of the opportunities?

- Strengths and Threats (ST)—How can you take advantage of your strengths to avoid real and potential threats?

- Weaknesses and Opportunities (WO)—How can you use your opportunities to overcome the weaknesses you are experiencing?

- Weaknesses and Threats (WT)—How can you minimize your weaknesses and avoid threats?

Most importantly, a SWOT analysis needs to both draw a set of concrete conclusions from the firm’s specific situation and identify a set of strategic actions to address each. The ultimate goal is to match the company’s resource strengths and market opportunities, correct important weaknesses, and defend against external threats.

Internal Analysis Tools

While SWOT helps you identify an organization’s strengths and weaknesses, there are other tools available for internal analysis too; notably value chain and VRIO analysis. In effect, value chain analysis asks you to take the organization apart and identify its important constituent parts. Sometimes these parts take the form of functions, like marketing or manufacturing.

Example 1.4 – Value Chain Analysis

B.Good is a restaurant chain that self-produces its ingredients and provides seasonal menus. This restaurant chain has 74 locations worldwide and 64 of them are located across the US. This business has some important functions that constitute its value chain. In an interview, B.Good’s director of supply chain, Joe Cloud, said that inventory and vendor management is crucial to maintaining the food safety of the restaurants and, therefore, enhance the business’s competitive advantage.

Source: Fast Casual, How transparency, technology help B.Good control supply chain, 2019Wi

Value chain functions are also called capabilities. This is where VRIO comes in. VRIO stands for valuable, rare, inimitable, and organization—basically, the VRIO framework suggests that a capability, or a resource, such as a patent or great location, is likely to yield a competitive advantage to an organization when it can be shown that it is valuable, rare, difficult to imitate, and supported by the organization (and, yes, this is the same organization that you find in P-O-L-C).[4] Essentially, where the value chain might suggest internal areas of strength, VRIO helps you understand whether those strengths will give it a competitive advantage.

Example 1.5 – VRIO Analysis

When Netflix first transitioned from physical disk to online streaming, companies such as BlockBusters did not think the new strategy would be a threat or a viable business model; hence they rejected the 50 million dollar offer to buy the company. Today, Netflix is worth an estimated 166.78 Billion dollars. But as the online streaming business model matures, companies with deeper pockets are trying to compete with Netflix for the market. This article analyses the current competitive edge of Netflix and the resources they need to succeed long term.

Source: Rancord Society, Netflix VRIO/VRIN Analysis & Value Chain Analysis (Resource-Based View), YanLin Zhu 2020Wi

External Analysis Tools

While there are probably hundreds of different ways for you to study an organization’s external environment, the two primary tools are PESTEL and industry analysis. PESTEL, as you probably guessed, is simply an acronym. It stands for political, economic, sociocultural, technological, environmental, and legal environments. Simply, the PESTEL framework directs you to collect information about, and analyze, each environmental dimension to identify the broad range of threats and opportunities facing the organization. Industry analysis, in contrast, asks you to map out the different relationships that the organization might have with suppliers, customers, and competitors. PESTEL provides you with a good sense of the broader macro-environment, whereas industry analysis should tell you about the organization’s competitive environment and the key industry-level factors that seem to influence performance.

Example 1.6 – PESTEL Analysis

The housing market in Boise, ID is experiencing immense price growth. Real estate companies are analyzing this increase using factors from the PESTEL analysis model. For example, they explain that one draw is environmental reasons (mild climate, outdoor activities). Another example is because the economy is growing, as HP, Micron Technologies, and other large companies are employing many in that area.

Source: Market Watch, The hottest housing markets of 2020 are far from the coasts, Tanner Harris 2020Wi

- Carpenter, M. A., & Sanders, W. G. (2009). Strategic management (p. 8). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Prentice-Hall. ↵

- Carpenter, M. A., & Sanders, W. G. (2009). Strategic management (p. 10). ↵

- Mintzberg, H. 1978. Patterns in strategy formulation. Management Science, 24, 934–949. ↵

- Don’t be confused, another internal analysis model we will use in this course (value chain analysis) will use similar terms to describe a core competency—valuable, rare, costly to imitate, and non-substitutable. ↵