Internal Analysis

By exploiting internal resources and capabilities and meeting the demanding standards of global competition, firms create value for customers.[1] Value is measured by a product’s performance characteristics and by its attributes for which customers are willing to pay.[2] Those particular bundles of resources and capabilities that provide unique advantages to the firm are considered core competencies.[3] Core competencies are resources and capabilities that serve as a source of a firm’s competitive advantage over rivals. Core competencies distinguish a company competitively and reflect its personality. Core competencies emerge over time through an organizational process of accumulating and learning how to deploy different resources and capabilities. As the capacity to take action, core competencies are “crown jewels of a company,” the activities the company performs especially well compared to competitors and through which the firm adds unique value to its goods or services over a long period of time.[4]

Example 4.2 Core Competency

Apple is a prime example of a company that identified it’s core competencies and uses them to the company’s advantage. The company has capitalized on Innovation, Marketing, and Brand Recognition as their core competencies. Apple is known for its rapid and successful innovation. Due to this, consumers are always waiting for Apple to roll out new, innovative products, playing into their core competencies. Brand Recognition plays a large role in consumer loyalty, and Apple customers are known for their vigorous loyalty. The company customizes its products to fit the needs of its customers and has been a consistent winner of awards for its marketing excellence.

Source: The Balance Small Business, Susan Ward, The Definition of Core Competency in Relation to Business, Lauren Thomas, 2020Sp

During the past several decades, the strategic management process was concerned largely with understanding the characteristics of the industry in which the firm competes and, in light of those characteristics, determining how the firm should position itself relative to competitors. This emphasis on industry characteristics and competitive strategy may have understated the role of the firm’s resources and capabilities in developing competitive advantage. In the current competitive landscape, core competencies, in combination with product-market positions, are the firm’s most important sources of competitive advantage.[5] The core competencies of a firm, in addition to its analysis of its general, industry, and competitor environments, should drive its selection of strategies. As Clayton Christensen noted, “Successful strategists need to cultivate a deep understanding of the processes of competition and progress and of the factors that undergird each advantage. Only thus will they be able to see when old advantages are poised to disappear and how new advantages can be built in their stead.”[6] By drawing on internal analysis and emphasizing core competencies when formulating strategies, companies learn to compete primarily on the basis of firm-specific differences, but they must be aware of how things are changing as well.

Example 4.3 Leveraging Resources

Netflix has used their internally generated customer data to understand their customers better market their products and service. By analyzing behaviors, Netflix is able to consistently and successfully fulfill their customer’s wishes and needs. For Netflix, “75% of Netflix viewer activity is driven by recommendation…Netflix’s recommendation system saves the company an estimated $1 billion per year through reduced churn” (DeAsi).

Source: Pointillist, How to Use Customer Behavior Data to Drive Revenue (Like Amazon, Netflix & Google), 2019 Sp

Resources and Capabilities

Resources

Broad in scope, the term resources covers a spectrum of individual, social, and organizational phenomena.[7] Typically, resources alone do not yield a competitive advantage.[8] In fact, the core competencies that yield a competitive advantage are created through the unique bundling of several resources.[9]

Some of a firm’s resources are tangible while others are intangible. Tangible resources are assets that can be seen and quantified. Production equipment, manufacturing plants, and formal reporting structures are examples of tangible resources. Intangible resources typically include assets that are rooted deeply in the firm’s history and have accumulated over time. Because they are embedded in unique patterns of routines, intangible resources are relatively difficult for competitors to analyze and imitate. Knowledge, trust between managers and employees, ideas, the capacity for innovation, managerial capabilities, organizational routines (the unique ways people work together), scientific capabilities, and the firm’s reputation for its goods or services and how it interacts with people (such as employees, customers, and suppliers) are all examples of intangible resources.[10] The four types of tangible resources are financial, organizational, physical, and technological. The three types of intangible resources are human, innovation, and reputational.

As a manager or entrepreneur, you will be challenged to understand the strategic value of your firm’s tangible and intangible resources. The strategic value of resources is indicated by the degree to which they can contribute to the development of core competencies, and, ultimately, competitive advantage. For example, as a tangible resource, a distribution facility is assigned a monetary value on the firm’s balance sheet. The real value of the facility, however, is grounded in a variety of factors, such as its proximity to raw materials and customers, but also in intangible factors such as the manner in which workers integrate their actions internally and with other stakeholders, such as suppliers and customers.[11]

Capabilities

Capabilities are the firm’s capacity to deploy resources that have been purposely integrated to achieve a desired end state.[12] As the glue that holds an organization together, capabilities emerge over time through complex interactions among tangible and intangible resources. They can be tangible, like a business process that is automated, but most of them tend to be tacit and intangible. Critical to forming competitive advantages, capabilities are often based on developing, carrying, and exchanging information and knowledge through the firm’s human capital.[13] Because a knowledge base is grounded in organizational actions that may not be explicitly understood by all employees, repetition and practice increase the value of a firm’s capabilities.

The foundation of many capabilities lies in the skills and knowledge of a firm’s employees and, often, their functional expertise. Hence, the value of human capital in developing and using capabilities and, ultimately, core competencies cannot be overstated. Firms committed to continuously developing their people’s capabilities seem to accept the adage that “the person who knows how will always have a job. The person who knows why will always be his boss.”[14]

Example 4.4 Advantage through the Value Chain

With a combined total export revenue of around US$5.2 million in the past 3 years, Myanmar’s local coffee industry has experienced tremendous growth. Up to this point, Myanmar’s smallholder coffee farmers sold their raw green coffee beans in a commodity-like market. Their roasting processes were traditional and low efficiency, they produced a poor quality product. But all of that changed in 2015 thanks to a collaboration between the U.S.-funded Value Chain for Rural Areas and the Myanmar Coffee Association. The Ywangan Coffee Cluster now consists of more than 10,000 coffee growers producing high quality Arabica beans and exports in the most recent year exceeded 477 metric tons to Europe, the U.S., and numerous Asian markets.

Improved techniques led to better quality products which in turn led to greater demand. Coffee producers have had to modernize their methods to keep up. One coffee producer Daw Su Su Ang, known as “the Coffee Lady” and owner of Amara Coffee, said that the Value Chain program has helped the factory to host training sessions to improve bean taste and pass down knowledge of natural processing methods while generating better wages for 300 families in 20 villages. Their output doubled in the past year.

Source: Irrawaddy, Shan State’s “Coffee Lady” Moves up the Value Chain, 2019Wi

Global business leaders increasingly support the view that the knowledge possessed by human capital is among the most significant of an organization’s capabilities and may ultimately be at the root of all competitive advantages. But firms must also be able to use the knowledge that they have and transfer it among their operating businesses.[15] For example, researchers have suggested that “in the information age, things are ancillary, knowledge is central. A company’s value derives not from things, but from knowledge, know-how, intellectual assets, and competencies—all of it embedded in people.”[16] Given this reality, the firm’s challenge is to create an environment that allows people to fit their individual pieces of knowledge together so that, collectively, employees possess as much organizational knowledge as possible.[17]

To help them develop an environment in which knowledge is widely spread across all employees, some organizations have created a new upper-level managerial position of chief learning officer (CLO). Establishing a CLO position highlights a firm’s belief that “future success will depend on competencies that traditionally have not been actively managed or measured—including creativity and the speed with which new ideas are learned and shared.”[18] In general, these firm should manage knowledge in ways that will support its efforts to create value for customers.[19]

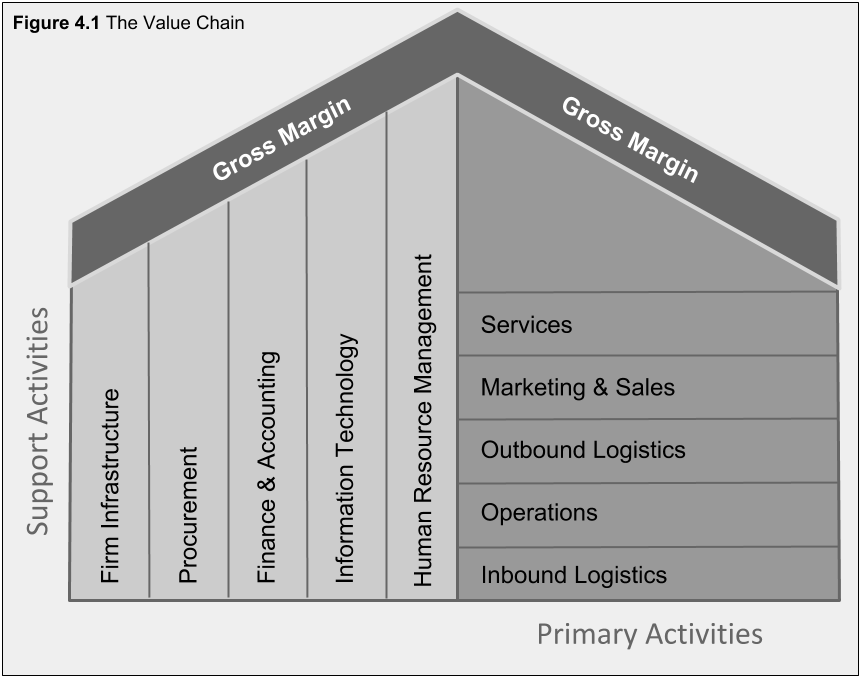

Capabilities are often developed in specific functional areas (such as manufacturing, R&D, and marketing) or in a part of a functional area (for example, advertising). The value chain, popularized by Michael Porter’s book, Competitive Advantage, is a useful tool for taking stock of organizational capabilities. A value chain is a chain of activities. In the value chain, some of the activities are deemed to be primary, in the sense that these activities add direct value. In the preceding figure, primary activities are logistics (inbound and outbound), marketing, and service. Support activities include how the firm is organized (infrastructure), human resources, technology, and procurement. Products pass through all activities of the chain in order, and at each activity, the product gains some value. A firm is effective to the extent that the chain of activities gives the products more added value than the sum of the costs at each step. While both primary and support activities add to a firm’s cost structure, due to their enabling nature, support activities are often candidates for outsourcing. Distinguishing between the two types of activities is a critical first step in understanding the firm’s value chain. Firms do not outsource primary activities if they are a source of competitive advantage.

It is important not to mix the concept of the value chain with the costs occurring throughout the value chain activities. A diamond cutter can be used as an example of the difference. The cutting activity may have a low cost, but the activity adds to much of the value of the end product, since a rough diamond is significantly less valuable than a cut, polished diamond. Research suggests a relationship between capabilities developed in particular functional areas and the firm’s financial performance at both the corporate and business-unit levels,[20] suggesting the need to develop capabilities at both levels.

- McEvily, S. K., & Chakravarthy, B. (2002). The persistence of knowledge-based advantage: An empirical test for product performance and technological knowledge. Strategic Management Journal, 23, 285–305; Buckley, P. J., & Carter, M. J. (2000). Knowledge management in global technology markets: Applying theory to practice. Long Range Planning, 33(1), 55–71. ↵

- Pocket Strategy. (1998). Value (p. 165). London: The Economist Books. ↵

- Prahalad, C. K., and Hamel, G. (1990). The core competence of the organization. Harvard Business Review, 90, 79–93. ↵

- Hafeez, K., Zhang, Y. B., & Malak, N. (2002). Core competence for sustainable competitive advantage: A structured methodology for identifying core competence. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 49(1), 28–35; Prahalad, C. K., & Hamel, G. (1990). The core competence of the corporation. Harvard Business Review, 68(3), 79–93. ↵

- Hitt, M. A., Nixon, R. D., Clifford, P. G., & Coyne, K. P. (1999). The development and use of strategic resources. In M. A. Hitt, P. G. Clifford, R. D. Nixon, & K. P. Coyne (Eds.), Dynamic Strategic Resources (pp. 1–14). Chichester: Wiley. ↵

- Christensen, C. M. (2001). The past and future of competitive advantage. Sloan Management Review, 42(2), 105–109. ↵

- Eisenhardt, K., & Martin, J. (2000). Dynamic capabilities: What are they? Strategic Management Journal, 21, 1105–1121; Michalisin, M. D., Kline, D. M., & Smith. R. D. (2000). Intangible strategic assets and firm performance: A multi-industry study of the resource-based view, Journal of Business Strategies, 17(2), 91–117. ↵

- West, G. P., & DeCastro, J. (2001). The Achilles heel of firm strategy: Resource weaknesses and distinctive inadequacies. Journal of Management Studies, 38(3), 26–45.; Deeds, D. L., DeCarolis, D., & J. Coombs. (2000). Dynamic capabilities and new product development in high technology ventures: An empirical analysis of new biotechnology firms. Journal of Business Venturing, 15, 211–229; Chi, T. (1994). Trading in strategic resources: Necessary conditions, transaction cost problems, and choice of exchange structure. Strategic Management Journal, 15, 271–290. ↵

- Berman, S., Down, J., & Hill, C. (2002). Tacit knowledge as a source of competitive advantage in the National Basketball Association. Academy of Management Journal, 45, 13–31. ↵

- Feldman, M. S. (2000). Organizational routines as a source of continuous change, Organization Science, 11, 611–629; Knott, A. M., & McKelvey, B. (1999). Nirvana efficiency: A comparative test of residual claims and routines. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 38, 365–383. ↵

- Gavetti, G., & Levinthal, D. (2000). Looking forward and looking backward: Cognitive and experiential search. Administrative Science Quarterly, 45, 113–137; Coff, R. W. (1999). How buyers cope with uncertainty when acquiring firms in knowledge-intensive industries: Caveat emptor. Organization Science, 10, 144–161; Marsh, S. J., & Ranft, A. L. (1999). Why resources matter: An empirical study of knowledge-based resources on new market entry. In M. A. Hitt, P. G. Clifford, R. D. Nixon, & K. P. Coyne (Eds.), Dynamic strategic resources (pp. 43–66). Chichester: Wiley. ↵

- Helfat, C. E., & Raubitschek, R. S. (2000). Product sequencing: Co-evolution of knowledge, capabilities, and products. Strategic Management Journal, 21, 961–979. ↵

- Hitt, M. A., Bierman, L., Shimizu, K., & Kochhar, R. (2001) Direct and moderating effects of human capital on strategy and performance in professional service firms: A resource-based perspective. Academy of Management Journal, 44(1), 13–28; Hitt, M. A., Ireland, R. D., & Lee, H. (2000). Technological learning, knowledge management, firm growth and performance: An introductory essay. Journal of Engineering and Technology Management, 17, 231–246; Hoopes, D. G., & Postrel, S. (1999). Shared knowledge: “Glitches,” and product development performance. Strategic Management Journal, 20, 837–865; Quinn, J. B. (1994).The Intelligent Enterprise. New York: Free Press. ↵

- Thoughts on the business of life. (1999, May 17). Forbes, p. 352. ↵

- Argote, L., & Ingram, P. (2000). Knowledge transfer: A basis for competitive advantage in firms. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 82, 150–169. ↵

- Dess, G. G., & Picken, J. C. (1999). Beyond productivity. New York: AMACOM. 26. ↵

- Coy, P. (2002, Spring). High turnover, high risk [Special Issue]. Business Week, p. 24. ↵

- Baldwin, T. T., & Danielson, C. C. (2000). Building a learning strategy at the top: Interviews with ten of America’s CLOs. Business Horizons, 43(6), 5–14. ↵

- Kuratko, D. F., Ireland, R. D., & Hornsby, J. S. (2001). Improving firm performance through entrepreneurial actions: Acordia’s corporate entrepreneurship strategy. Academy of Management Executive, 15(4), 60–71; Hansen, M. T., Nhoria, N., & Tierney, T. (1999). What’s your strategy for managing knowledge? Harvard Business ↵

- Hitt, M. A., & Ireland, R. D. (1986). Relationships among corporate level distinctive competencies, diversification strategy, corporate structure, and performance. Journal of Management Studies, 23, 401–416; Hitt, M. A., & Ireland, R. D. (1985). Corporate distinctive competence, strategy, industry, and performance. Strategic Management Journal, 6, 273–293; Hitt, M. A., Ireland, R. D., & Palia, K. A. (1982). Industrial firms’ grand strategy and functional importance. Academy of Management Journal, 25, 265–298; Hitt, M. A., Ireland, R. D., & Stadter, G. (1982). Functional importance and company performance: Moderating effects of grand strategy and industry type. Strategic Management Journal, 3, 315–330; Snow, C. C., & Hrebiniak, E. G. (1980). Strategy, distinctive competence, and organizational performance. Administrative Science Quarterly, 25, 317–336. ↵