Voting Rights

Voting Districts or Redistricting and Race

Gomillion v. Lightfoot (1960)

364 U.S. 339 (1960)

Vote: 9-0

Decision: Reversed

Majority: Frankfurter, joined by Warren, Black, Douglas, Clark, Harlan, Brennan, and Stewart

Concurrence: Whittaker

MR. JUSTICE FRANKFURTER delivered the opinion of the Court.

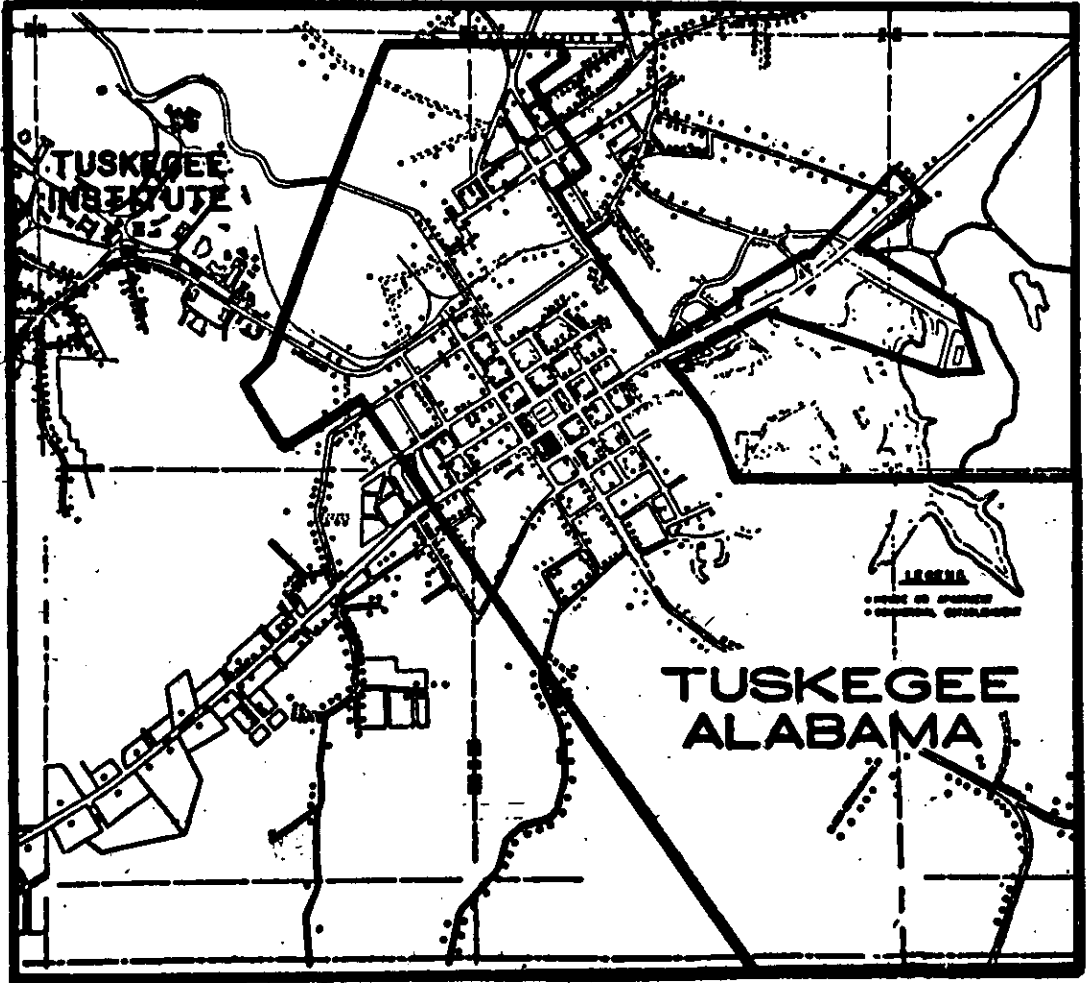

This litigation challenges the validity, under the United States Constitution, of Local Act No. 140, passed by the Legislature of Alabama in 1957, redefining the boundaries of the City of Tuskegee. Petitioners, Negro citizens of Alabama who were, at the time of this redistricting measure, residents of the City of Tuskegee, brought an action in the United States District Court for the Middle District of Alabama for a declaratory judgment that Act 140 is unconstitutional, and for an injunction to restrain the Mayor and officers of Tuskegee and the officials of Macon County, Alabama, from enforcing the Act against them and other Negroes similarly situated. Petitioners’ claim is that enforcement of the statute, which alters the shape of Tuskegee from a square to an uncouth twenty-eight-sided figure, will constitute a discrimination against them in violation of the Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution and will deny them the right to vote in defiance of the Fifteenth Amendment.

The respondents moved for dismissal of the action for failure to state a claim upon which relief could be granted and for lack of jurisdiction of the District Court. The court granted the motion, stating,

“This Court has no control over, no supervision over, and no power to change any boundaries of municipal corporations fixed by a duly convened and elected legislative body, acting for the people in the State of Alabama.”

On appeal, the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, affirmed … We brought the case here since serious questions were raised concerning the power of a State over its municipalities in relation to the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments.

At this stage of the litigation, we are not concerned with the truth of the allegations, that is, the ability of petitioners to sustain their allegations by proof. The sole question is whether the allegations entitle them to make good on their claim that they are being denied rights under the United States Constitution. The complaint, charging that Act 140 is a device to disenfranchise Negro citizens, alleges the following facts: Prior to Act 140 the City of Tuskegee was square in shape; the Act transformed it into a strangely irregular twenty-eight-sided figure.

The essential inevitable effect of this redefinition of Tuskegee’s boundaries is to remove from the city all save only four or five of its 400 Negro voters while not removing a single white voter or resident. The result of the Act is to deprive the Negro petitioners discriminatorily of the benefits of residence in Tuskegee, including, inter alia, the right to vote in municipal elections.

These allegations, if proven, would abundantly establish that Act 140 was not an ordinary geographic redistricting measure even within familiar abuses of gerrymandering. If these allegations upon a trial remained uncontradicted or unqualified, the conclusion would be irresistible, tantamount for all practical purposes to a mathematical demonstration, that the legislation is solely concerned with segregating white and colored voters by fencing Negro citizens out of town so as to deprive them of their pre-existing municipal vote.

It is difficult to appreciate what stands in the way of adjudging a statute having this inevitable effect invalid in light of the principles by which this Court must judge, and uniformly has judged, statutes that, howsoever speciously defined, obviously discriminate against colored citizens. “The [Fifteenth] Amendment nullifies sophisticated as well as simple-minded modes of discrimination.” Lane v. Wilson (1939).

The complaint amply alleges a claim of racial discrimination. Against this claim the respondents have never suggested, either in their brief or in oral argument, any countervailing municipal function which Act 140 is designed to serve. The respondents invoke generalities expressing the State’s unrestricted power—unlimited, that is, by the United States Constitution—to establish, destroy, or reorganize by contraction or expansion its political subdivisions, to wit, cities, counties, and other local units. …

… The Court has never acknowledged that the States have power to do as they will with municipal corporations regardless of consequences. …

… [S]uch power, extensive though it is, is met and overcome by the Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, which forbids a State from passing any law which deprives a citizen of his vote because of his race. The opposite conclusion, urged upon us by respondents, would sanction the achievement by a State of any impairment of voting rights whatever so long as it was cloaked in the grab of the realignment of political subdivisions. “It is inconceivable that guaranties embedded in the Constitution of the United States may thus be manipulated out of existence.” Frost & Frost Trucking Co. v. Railroad Commission of California (1926).

… A statute which is alleged to have worked unconstitutional deprivations of petitioners’ rights is not immune to attack simply because the mechanism employed by the legislature is a redefinition of municipal boundaries. According to the allegations here made, the Alabama Legislature has not merely redrawn the Tuskegee city limits with incidental inconvenience to the petitioners; it is more accurate to say that it has deprived the petitioners of the municipal franchise and consequent rights and to that end it has incidentally changed the city’s boundaries. While in form this is merely an act redefining metes and bounds, if the allegations are established, the inescapable human effect of this essay in geometry and geography is to despoil colored citizens, and only colored citizens, of their theretofore enjoyed voting rights

For these reasons, the principal conclusions of the District Court and the Court of Appeals are clearly erroneous and the decision below must be

Reversed.

MR. JUSTICE WHITTAKER, concurring.

I concur in the Court’s judgment, but not in the whole of its opinion. It seems to me that the decision should be rested not on the Fifteenth Amendment, but rather on the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution. I am doubtful that the averments of the complaint, taken for present purposes to be true, show a purpose by Act No. 140 to abridge petitioners’ “right … to vote” in the Fifteenth Amendment sense. It seems to me that the “right … to vote” that is guaranteed by the Fifteenth Amendment is but the same right to vote as is enjoyed by all others within the same election precinct, ward or other political division. And, inasmuch as no one has the right to vote in a political division, or in a local election concerning only an area in which he does not reside, it would seem to follow that one’s right to vote in Division A is not abridged by a redistricting that places his residence in Division B if he there enjoys the same voting privileges as all others in that Division, even though the redistricting was done by the State for the purpose of placing a racial group of citizens in Division B …

But it does seem clear to me that accomplishment of a State’s purpose — to use the Court’s phrase — of “fencing Negro citizens out of” Division A and into Division B is an unlawful segregation of races of citizens, in violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, Brown v. Board of Education (1954), Cooper v. Aaron (1958), and, as stated, I would think the decision should be rested on that ground — which, incidentally, clearly would not involve, just as the cited cases did not involve, the Colegrove problem.

Thornburgh v. Gingles (1986)

478 U.S. 30 (1986)

Note: This is a statutory case but the decision here is important for understanding the next two cases; thus, a short excerpt has been included.

Vote: 9-0

Decision: Affirmed in part and reversed in part

Majority: Brennan Burger, joined by Burger, White, Marshall, Blackmun, Powell, Rehnquist, Stevens, and O’Connor

JUSTICE BRENNAN announced the judgment of the Court and delivered the opinion of the Court with respect to Parts I, II, III-A, III-B, IV-A, and V, an opinion with respect to Part III-C, in which JUSTICE MARSHALL, JUSTICE BLACKMUN, and JUSTICE STEVENS join, and an opinion with respect to Part IV-B, in which JUSTICE WHITE joins.

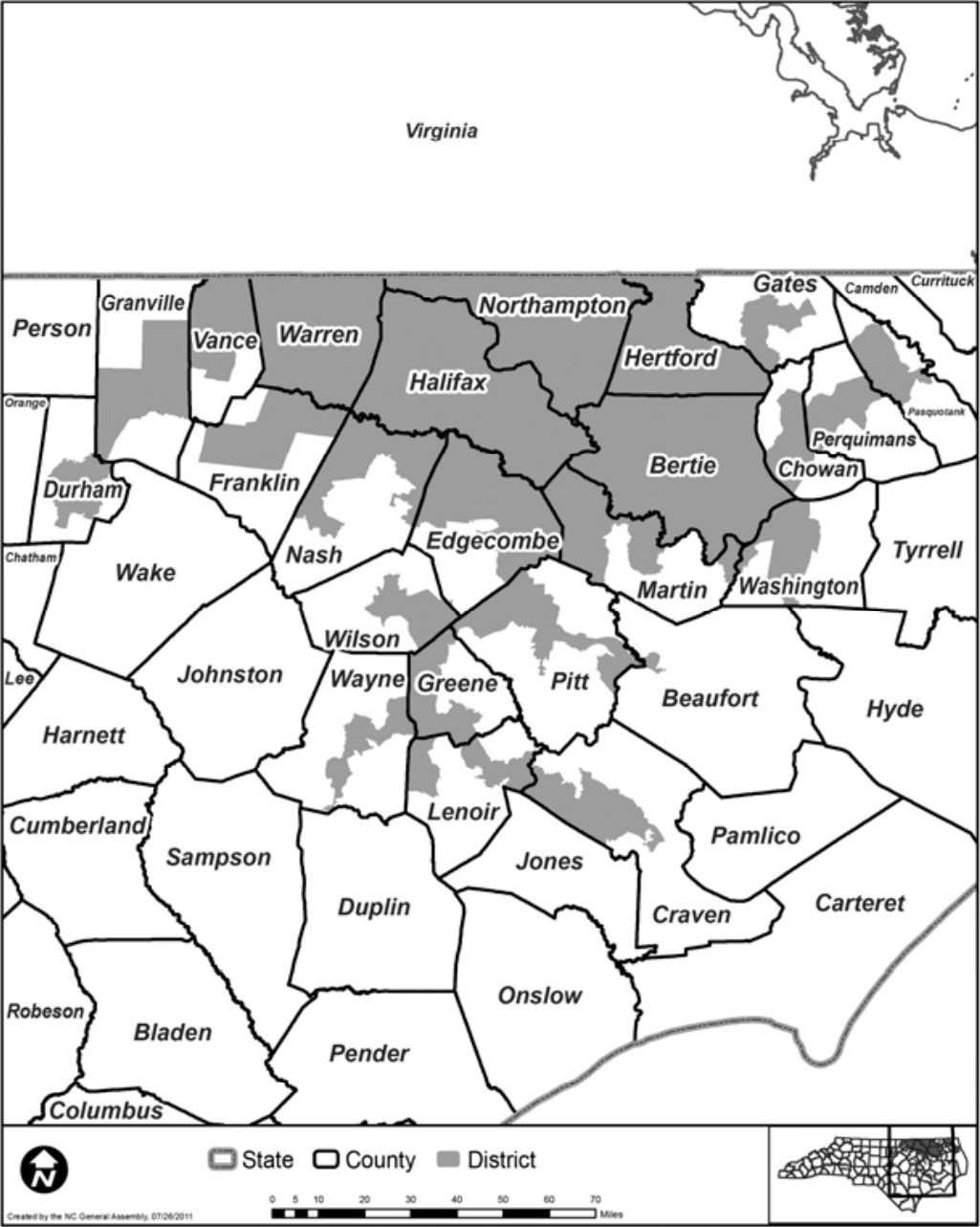

This case requires that we construe for the first time § 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, as amended June 29, 1982. 42 U.S.C. § 1973. The specific question to be decided is whether the three-judge District Court, convened in the Eastern District of North Carolina pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 2284(a) and 42 U.S.C. § 1973c, correctly held that the use in a legislative redistricting plan of multimember districts in five North Carolina legislative districts violated § 2 by impairing the opportunity of black voters “to participate in the political process and to elect representatives of their choice.” § 2(b), 96 Stat. 134.

…

Preliminarily, the [District] court found that black citizens constituted a distinct population and registered-voter minority in each challenged district. The court noted that, at the time the multimember districts were created, there were concentrations of black citizens within the boundaries of each that were sufficiently large and contiguous to constitute effective voting majorities in single-member districts lying wholly within the boundaries of the multimember districts. With respect to the challenged single-member district, Senate District No. 2, the court also found that there existed a concentration of black citizens within its boundaries and within those of adjoining Senate District No. 6 that was sufficient in numbers and in contiguity to constitute an effective voting majority in a single-member district. The District Court then proceeded to find that the following circumstances combined with the multimember districting scheme to result in the dilution of black citizens’ votes.

Based on these findings, the court declared the contested portions of the 1982 redistricting plan violative of § 2, and enjoined appellants from conducting elections pursuant to those portions of the plan … We noted probable jurisdiction, 471 U.S. 1064 (1985), and now affirm with respect to all of the districts except House District 23. With regard to District 23, the judgment of the District Court is reversed.

…

Because loss of political power through vote dilution is distinct from the mere inability to win a particular election, Whitcomb (1971), a pattern of racial bloc voting that extends over a period of time is more probative of a claim that a district experiences legally significant polarization than are the results of a single election …

…

Summary

In sum, we would hold that the legal concept of racially polarized voting, as it relates to claims of vote dilution, refers only to the existence of a correlation between the race of voters and the selection of certain candidates. Plaintiffs need not prove causation or intent in order to prove a prima facie case of racial bloc voting, and defendants may not rebut that case with evidence of causation or intent.

…

The District Court in this case carefully considered the totality of the circumstances and found that, in each district, racially polarized voting; the legacy of official discrimination in voting matters, education, housing, employment, and health services; and the persistence of campaign appeals to racial prejudice acted in concert with the multimember districting scheme to impair the ability of geographically insular and politically cohesive groups of black voters to participate equally in the political process and to elect candidates of their choice. It found that the success a few black candidates have enjoyed in these districts is too recent, too limited, and, with regard to the 1982 elections, perhaps too aberrational, to disprove its conclusion. Excepting House District 23, with respect to which the District Court committed legal error, see supra, at Thornburg v. Gingles (1986), we affirm the District Court’s judgment. We cannot say that the District Court, composed of local judges who are well acquainted with the political realities of the State, clearly erred in concluding that use of a multimember electoral structure has caused black voters in the districts other than House District 23 to have less opportunity than white voters to elect representatives of their choice.

The judgment of the District Court is

Affirmed in part and reversed in part.

Shaw v. Reno (1993)

509 U.S. 630 (1993)

Vote: 5-4

Decision: Reversed

Majority: O’Connor, joined by Rehnquist, Scalia, Kennedy, and Thomas

Dissent: White, joined by Blackmun, Stevens, and Souter

O’Connor, J., delivered the opinion for a unanimous Court.

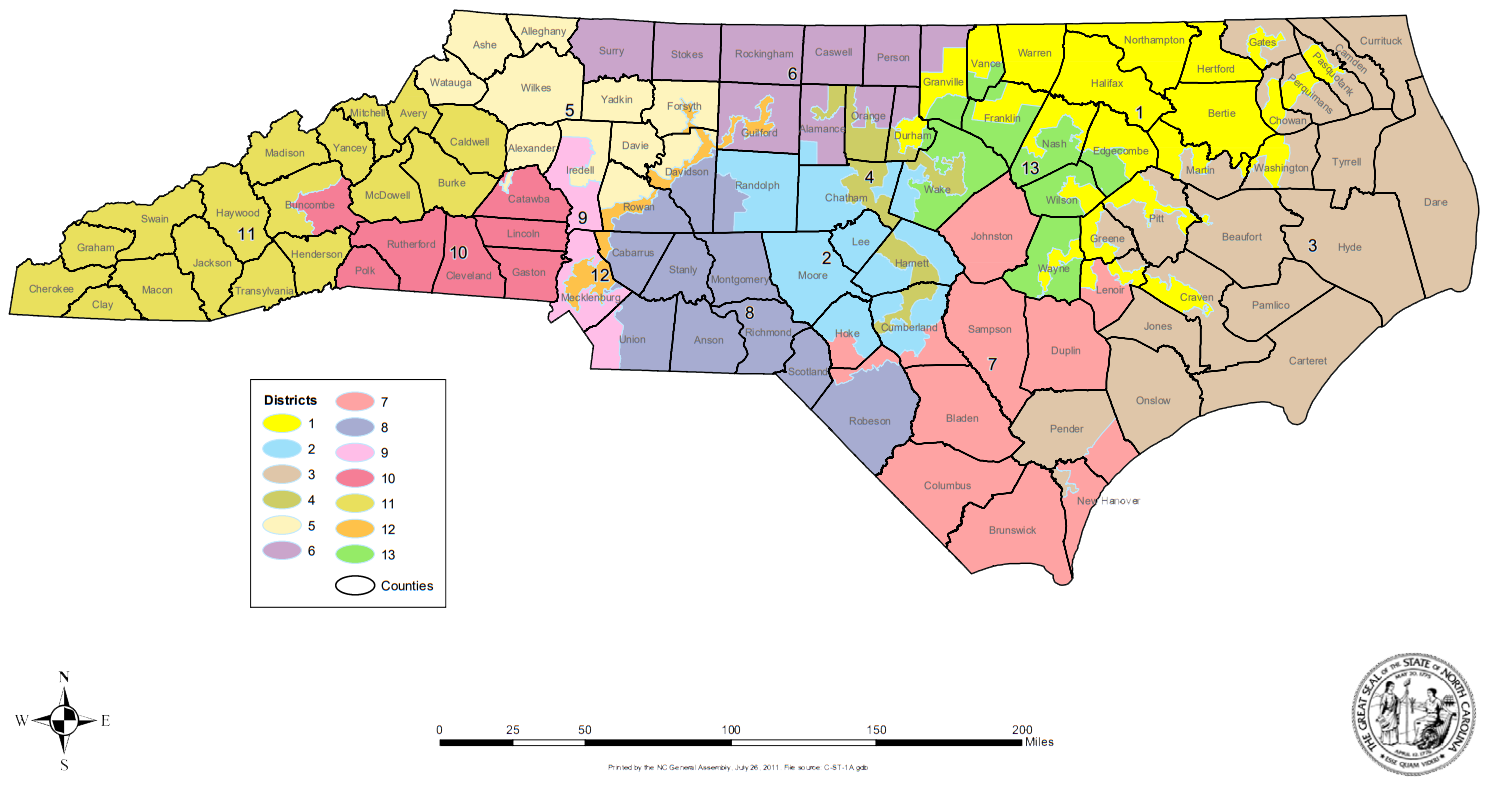

This case involves two of the most complex and sensitive issues this Court has faced in recent years: the meaning of the constitutional “right” to vote, and the propriety of racebased state legislation designed to benefit members of historically disadvantaged racial minority groups. As a result of the 1990 census, North Carolina became entitled to a 12th seat in the United States House of Representatives. The General Assembly enacted a reapportionment plan that included one majority-black congressional district. After the Attorney General of the United States objected to the plan pursuant to § 5 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, 79 Stat. 439, as amended, 42 U. S. C. § 1973c, the General Assembly passed new legislation creating a second majority-black district. Appellants allege that the revised plan, which contains district boundary lines of dramatically irregular shape, constitutes an unconstitutional racial gerrymander. The question before us is whether appellants have stated a cognizable claim.

The voting age population of North Carolina is approximately 78% white, 20% black, and 1% Native American; the remaining 1% is predominantly Asian. App. to Brief for Federal Appellees 16a. The black population is relatively dispersed; blacks constitute a majority of the general population in only 5 of the State’s 100 counties. Brief for Appellants 57. Geographically, the State divides into three regions: the eastern Coastal Plain, the central Piedmont Plateau, and the western mountains. H. Lefler & A. Newsom, The History of a Southern State: North Carolina 18-22 (3d ed. 1973). The largest concentrations of black citizens live in the Coastal Plain, primarily in the northern part. O. Gade & H. Stillwell, North Carolina: People and Environments 65-68 (1986).

Forty of North Carolina’s one hundred counties are covered by § 5 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, 42 U. S. C. § 1973c, which prohibits a jurisdiction subject to its provisions from implementing changes in a “standard, practice, or procedure with respect to voting” without federal authorization, ibid. … Because the General Assembly’s reapportionment plan affected the covered counties, the parties agree that § 5 applied. Tr. of Oral Arg. 14, 27-29. The State chose to submit its plan to the Attorney General for preclearance.

The Attorney General, acting through the Assistant Attorney General for the Civil Rights Division, interposed a formal objection to the General Assembly’s plan. The Attorney General specifically objected to the configuration of boundary lines drawn in the south-central to southeastern region of the State. In the Attorney General’s view, the General Assembly could have created a second majorityminority district “to give effect to black and Native American voting strength in this area” by using boundary lines “no more irregular than [those] found elsewhere in the proposed plan,” but failed to do so for “pretextual reasons.” See App. to Brief for Federal Appellees lOa-lla.

… Instead, the General Assembly enacted a revised redistricting plan, 1991 N. C. Extra Sess. Laws, ch. 7, that included a second majority-black district. The General Assembly located the second district not in the south-central to southeastern part of the State, but in the north-central region along Interstate 85.

The first of the two majority-black districts contained in the revised plan, District 1, is somewhat hook shaped. Centered in the northeast portion of the State, it moves southward until it tapers to a narrow band; then, with finger-like extensions, it reaches far into the southernmost part of the State near the South Carolina border. District 1 has been compared to a “Rorschach ink-blot test,” Shaw v. Barr (1992) (Voorhees, C. J., concurring in part and dissenting in part), and a “bug splattered on a windshield,” Wall Street Journal, Feb. 4, 1992, p. A14.

The second majority-black district, District 12, is even more unusually shaped. It is approximately 160 miles long and, for much of its length, no wider than the 1-85 corridor. It winds in snakelike fashion through tobacco country, financial centers, and manufacturing areas “until it gobbles in enough enclaves of black neighborhoods.” 808 F. Supp., at 476-477 (Voorhees, C. J., concurring in part and dissenting in part). Northbound and southbound drivers on 1-85 sometimes find themselves in separate districts in one county, only to “trade” districts when they enter the next county. Of the 10 counties through which District 12 passes, 5 are cut into 3 different districts; even towns are divided. At one point the district remains contiguous only because it intersects at a single point with two other districts before crossing over them. See Brief for Republican National Committee as Amicus Curiae 14-15 …

The Attorney General did not object to the General Assembly’s revised plan. But numerous North Carolinians did … alleging that the plan constituted an unconstitutional political gerrymander under Davis v. Bandemer (1986). That claim was dismissed, see Pope v. Blue (1992), and this Court summarily affirmed

Shortly after the complaint in Pope v. Blue was filed, appellants instituted the present action in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of North Carolina. Appellants alleged not that the revised plan constituted a political gerrymander, nor that it violated the “one person, one vote” principle, see Reynolds v. Sims (1964), but that the State had created an unconstitutional racial gerrymander.

…

Appellants contended that the General Assembly’s revised reapportionment plan violated several provisions of the United States Constitution, including the Fourteenth Amendment. They alleged that the General Assembly deliberately “create[d] two Congressional Districts in which a majority of black voters was concentrated arbitrarily-without regard to any other considerations, such as compactness, contiguousness, geographical boundaries, or political subdivisions” with the purpose “to create Congressional Districts along racial lines” and to assure the election of two black representatives to Congress. App. to Juris. Statement 102a.

…

By a 2-to-1 vote, the District Court also dismissed the complaint against the state appellees. The majority found no support for appellants’ contentions that race-based districting is prohibited by Article I, § 4, or Article I, § 2, of the Constitution, or by the Privileges and Immunities Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

…

We noted probable jurisdiction. 506 U. S. 1019 (1992).

“The right to vote freely for the candidate of one’s choice is of the essence of a democratic society. …” Reynolds v. Sims (1964). For much of our Nation’s history, that right sadly has been denied to many because of race. The Fifteenth Amendment, ratified in 1870 after a bloody Civil War, promised unequivocally that “[t]he right of citizens of the United States to vote” no longer would be “denied or abridged … by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” U. S. Const., Amdt. 15, § 1.

But “[a] number of states … refused to take no for an answer and continued to circumvent the fifteenth amendment’s prohibition through the use of both subtle and blunt instruments, perpetuating ugly patterns of pervasive racial discrimination.” Blumstein, Defining and Proving Race Discrimination: Perspectives on the Purpose V s. Results Approach from the Voting Rights Act, 69 Va. L. Rev. 633, 637 (1983) …

Another of the weapons in the States’ arsenal was the racial gerrymander-“the deliberate and arbitrary distortion of district boundaries … for [racial] purposes.” Bandemer (1986) (Powell, J., concurring in part and dissenting in part) …

But it soon became apparent that guaranteeing equal access to the polls would not suffice to root out other racially discriminatory voting practices. Drawing on the “one person, one vote” principle, this Court recognized that “[t]he right to vote can be affected by a dilution of voting power as well as by an absolute prohibition on casting a ballot.” … Accordingly, the Court held that such schemes violate the Fourteenth Amendment when they are adopted with a discriminatory purpose and have the effect of diluting minority voting strength. Congress, too, responded to the problem of vote dilution. In 1982, it amended § 2 of the Voting Rights Act to prohibit legislation that results in the dilution of a minority group’s voting strength, regardless of the legislature’s intent. 42 U. S. C. § 1973; see Thornburg v. Gingles (1986) (applying amended § 2 to vote-dilution claim involving multimember districts); see also Voinovich v. Quilter (1993) (single-member districts).

It is against this background that we confront the questions presented here. In our view, the District Court properly dismissed appellants’ claims against the federal appellees. Our focus is on appellants’ claim that the State engaged in unconstitutional racial gerrymandering. That argument strikes a powerful historical chord: It is unsettling how closely the North Carolina plan resembles the most egregious racial gerrymanders of the past.

An understanding of the nature of appellants’ claim is critical to our resolution of the case. In their complaint, appellants did not claim that the General Assembly’s reapportionment plan unconstitutionally “diluted” white voting strength. They did not even claim to be white. Rather, appellants’ complaint alleged that the deliberate segregation of voters into separate districts on the basis of race violated their constitutional right to participate in a “color-blind” electoral process.

Despite their invocation of the ideal of a “color-blind” Constitution, see Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) (Harlan, J., dissenting), appellants appear to concede that race-conscious redistricting is not always unconstitutional. See Tr. of Oral Arg. 16-19. That concession is wise: This Court never has held that race-conscious state decisionmaking is impermissible in all circumstances. What appellants object to is redistricting legislation that is so extremely irregular on its face that it rationally can be viewed only as an effort to segregate the races for purposes of voting, without regard for traditional districting principles and without sufficiently compelling justification. For the reasons that follow, we conclude that appellants have stated a claim upon which relief can be granted under the Equal Protection Clause.

The Equal Protection Clause provides that “[n]o State shall … deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” U. S. Const., Arndt. 14, § 1. Its central purpose is to prevent the States from purposefully discriminating between individuals on the basis of race …

Classifications of citizens solely on the basis of race “are by their very nature odious to a free people whose institutions are founded upon the doctrine of equality.” … Accordingly, we have held that the Fourteenth Amendment requires state legislation that expressly distinguishes among citizens because of their race to be narrowly tailored to further a compelling governmental interest.

Appellants contend that redistricting legislation that is so bizarre on its face that it is “unexplainable on grounds other than race,” Arlington Heights, supra, at 266, demands the same close scrutiny that we give other state laws that classify citizens by race. Our voting rights precedents support that conclusion.

…

… Gomillion thus supports appellants’ contention that district lines obviously drawn for the purpose of separating voters by race require careful scrutiny under the Equal Protection Clause regardless of the motivations underlying their adoption.

…

Put differently, we believe that reapportionment is one area in which appearances do matter. A reapportionment plan that includes in one district individuals who belong to the same race, but who are otherwise widely separated by geographical and political boundaries, and who may have little in common with one another but the color of their skin, bears an uncomfortable resemblance to political apartheid. It reinforces the perception that members of the same racial group-regardless of their age, education, economic status, or the community in which they live-think alike, share the same political interests, and will prefer the same candidates at the polls. We have rejected such perceptions elsewhere as impermissible racial stereotypes … By perpetuating such notions, a racial gerrymander may exacerbate the very patterns of racial bloc voting that majority-minority districting is sometimes said to counteract.

The message that such districting sends to elected representatives is equally pernicious. When a district obviously is created solely to effectuate the perceived common interests of one racial group, elected officials are more likely to believe that their primary obligation is to represent only the members of that group, rather than their constituency as a whole. This is altogether antithetical to our system of representative democracy …

For these reasons, we conclude that a plaintiff challenging a reapportionment statute under the Equal Protection Clause may state a claim by alleging that the legislation, though race neutral on its face, rationally cannot be understood as anything other than an effort to separate voters into different districts on the basis of race, and that the separation lacks sufficient justification. It is unnecessary for us to decide whether or how a reapportionment plan that, on its face, can be explained in nonracial terms successfully could be challenged. Thus, we express no view as to whether “the intentional creation of majority-minority districts, without more,” always gives rise to an equal protection claim. Post, at 668 (WHITE, J., dissenting). We hold only that, on the facts of this case, appellants have stated a claim sufficient to defeat the state appellees’ motion to dismiss.

…

Racial classifications of any sort pose the risk of lasting harm to our society. They reinforce the belief, held by too many for too much of our history, that individuals should be judged by the color of their skin. Racial classifications with respect to voting carry particular dangers. Racial gerrymandering, even for remedial purposes, may balkanize us into competing racial factions; it threatens to carry us further from the goal of a political system in which race no longer matters-a goal that the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments embody, and to which the Nation continues to aspire. It is for these reasons that race-based districting by our state legislatures demands close judicial scrutiny.

In this case, the Attorney General suggested that North Carolina could have created a reasonably compact second majority-minority district in the south-central to southeastern part of the State. We express no view as to whether appellants successfully could have challenged such a district under the Fourteenth Amendment. We also do not decide whether appellants’ complaint stated a claim under constitutional provisions other than the Fourteenth Amendment. Today we hold only that appellants have stated a claim under the Equal Protection Clause by alleging that the North Carolina General Assembly adopted a reapportionment scheme so irrational on its face that it can be understood only as an effort to segregate voters into separate voting districts because of their race, and that the separation lacks sufficient justification. If the allegation of racial gerrymandering remains uncontradicted, the District Court further must determine whether the North Carolina plan is narrowly tailored to further a compelling governmental interest.

Accordingly, we reverse the judgment of the District Court and remand the case for further proceedings consistent with this opinion.

It is so ordered.

Miller v. Johnson (1995)

515 U.S. 900 (1995)

Vote: 5-4

Decision: Affirmed

Majority: Kennedy, joined by Rehnquist, O’Connor, Thomas, and Scalia

Concurrence: O’Connor

Dissent: Stevens

Dissent: Ginsburg, joined by Breyer, Stevens, and Souter (except as to Part III-B)

JUSTICE KENNEDY delivered the opinion of the Court.

The constitutionality of Georgia’s congressional redistricting plan is at issue here. In Shaw v. Reno, 509 U. S. 630 (1993), we held that a plaintiff states a claim under the Equal Protection Clause by alleging that a state redistricting plan, on its face, has no rational explanation save as an effort to separate voters on the basis of race. The question we now decide is whether Georgia’s new Eleventh District gives rise to a valid equal protection claim under the principles announced in Shaw, and, if so, whether it can be sustained nonetheless as narrowly tailored to serve a compelling governmental interest.

The Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment provides that no State shall “deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” U.S. Const., Amdt. 14, 1. Its central mandate is racial neutrality in governmental decisionmaking. The Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment provides that no State shall “deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” U.S. Const., Amdt. 14, 1. Its central mandate is racial neutrality in governmental decisionmaking … The Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment provides that no State shall “deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” U.S. Const., Amdt. 14, 1. Its central mandate is racial neutrality in governmental decisionmaking.

In Shaw v. Reno, we recognized that these equal protection principles govern a State’s drawing of congressional districts, though, as our cautious approach there discloses, application of these principles to electoral districting is a most delicate task …

This litigation requires us to apply the principles articulated in Shaw to the most recent congressional redistricting plan enacted by the State of Georgia …

In 1965, the Attorney General designated Georgia a covered jurisdiction under § 4(b) of the Voting Rights Act (Act) … In consequence, § 5 of the Act requires Georgia to obtain either administrative preclearance by the Attorney General or approval by the United States District Court for the District of Columbia of any change in a “standard, practice, or procedure with respect to voting” made after November 1, 1964 … The preclearance mechanism applies to congressional redistricting plans, and requires that the proposed change “not have the purpose and will not have the effect of denying or abridging the right to vote on account of race or color.” …”[T]he purpose of § 5 has always been to insure that no voting-procedure changes would be made that would lead to a retrogression in the position of racial minorities with respect to their effective exercise of the electoral franchise.” …

… Citing much evidence of the legislature’s purpose and intent in creating the final plan, as well as the irregular shape of the district (in particular several appendages drawn for the obvious purpose of putting black populations into the district), the court found that race was the overriding and predominant force in the districting determination. The [District] court proceeded to apply strict scrutiny. Though rejecting proportional representation as a compelling interest, it was willing to assume that compliance with the Act would be a compelling interest … [T]he court found that the Act did not require three majority-black districts, and that Georgia’s plan for that reason was not narrowly tailored to the goal of complying with the Act …

Finding that the “evidence of the General Assembly’s intent to racially gerrymander the Eleventh District is overwhelming, and practically stipulated by the parties involved,” the District Court held that race was the predominant, overriding factor in drawing the Eleventh District …

Appellants do not take issue with the court’s factual finding of this racial motivation. Rather, they contend that evidence of a legislature’s deliberate classification of voters on the basis of race cannot alone suffice to state a claim under Shaw. They argue that, regardless of the legislature’s purposes, a plaintiff must demonstrate that a district’s shape is so bizarre that it is unexplainable other than on the basis of race, and that appellees failed to make that showing here. Appellants’ conception of the constitutional violation misapprehends our holding in Shaw and the equal protection precedent upon which Shaw relied …

Our circumspect approach and narrow holding in Shaw did not erect an artificial rule barring accepted equal protection analysis in other redistricting cases. Shape is relevant not because bizarreness is a necessary element of the constitutional wrong or a threshold requirement of proof, but because it may be persuasive circumstantial evidence that race for its own sake, and not other districting principles, was the legislature’s dominant and controlling rationale in drawing its district lines. The logical implication, as courts applying Shaw have recognized, is that parties may rely on evidence other than bizarreness to establish race-based districting …

In sum, we make clear that parties alleging that a State has assigned voters on the basis of race are neither confined in their proof to evidence regarding the district’s geometry and makeup nor required to make a threshold showing of bizarreness. Today’s litigation requires us further to consider the requirements of the proof necessary to sustain this equal protection challenge …

The courts, in assessing the sufficiency of a challenge to a districting plan, must be sensitive to the complex interplay of forces that enter a legislature’s redistricting calculus. Redistricting legislatures will, for example, almost always be aware of racial demographics; but it does not follow that race predominates in the redistricting process …

The distinction between being aware of racial considerations and being motivated by them may be difficult to make. This evidentiary difficulty, together with the sensitive nature of redistricting and the presumption of good faith that must be accorded legislative enactments, requires courts to exercise extraordinary caution in adjudicating claims that a State has drawn district lines on the basis of race. The plaintiff’s burden is to show, either through circumstantial evidence of a district’s shape and demographics or more direct evidence going to legislative purpose, that race was the predominant factor motivating the legislature’s decision to place a significant number of voters within or without a particular district. To make this showing, a plaintiff must prove that the legislature subordinated traditional race-neutral districting principles, including but not limited to compactness, contiguity, and respect for political subdivisions or communities defined by actual shared interests, to racial considerations. Where these or other race-neutral considerations are the basis for redistricting legislation, and are not subordinated to race, a State can “defeat a claim that a district has been gerrymandered on racial lines.” …

In our view, the District Court applied the correct analysis, and its finding that race was the predominant factor motivating the drawing of the Eleventh District was not clearly erroneous. The court found it was “exceedingly obvious” from the shape of the Eleventh District, together with the relevant racial demographics, that the drawing of narrow land bridges to incorporate within the district outlying appendages containing nearly 80% of the district’s total black population was a deliberate attempt to bring black populations into the district …

To satisfy strict scrutiny, the State must demonstrate that its districting legislation is narrowly tailored to achieve a compelling interest … We do not accept the contention that the State has a compelling interest in complying with whatever preclearance mandates the Justice Department issues. When a state governmental entity seeks to justify race-based remedies to cure the effects of past discrimination, we do not accept the government’s mere assertion that the remedial action is required. Rather, we insist on a strong basis in evidence of the harm being remedied …

Instead of grounding its objections on evidence of a discriminatory purpose, it would appear the Government was driven by its policy of maximizing majority-black districts. Although the Government now disavows having had policy … and seems to concede its impropriety, the District Court’s well-documented factual finding was that the Department did adopt a maximization policy and followed it in objecting to Georgia’s first two plans …

The Act, and its grant of authority to the federal courts to uncover official efforts to abridge minorities’ right to vote, has been of vital importance in eradicating invidious discrimination from the electoral process and enhancing the legitimacy of our political institutions. Only if our political system and our society cleanse themselves of that discrimination will all members of the polity share an equal opportunity to gain public office regardless of race. As a Nation we share both the obligation and the aspiration of working toward this end. The end is neither assured nor well served, however, by carving electorates into racial blocs.”If our society is to continue to progress as a multiracial democracy, it must recognize that the automatic invocation of race stereotypes retards that progress and causes continued hurt and injury.” …

It takes a shortsighted and unauthorized view of the Voting Rights Act to invoke that statute, which has played a decisive role in redressing some of our worst forms of discrimination, to demand the very racial stereotyping the Fourteenth Amendment forbids.

The judgment of the District Court is affirmed, and the cases are remanded for further proceedings consistent with this decision.

It is so ordered.

Bush v. Vera (1996)

517 U.S. 952 (1996)

Vote: 5-4

Decision: Affirmed

Majority: O’Connor, joined by Rehnquist, and Kennedy

Concurrence: O’Connor

Concurrence: Kennedy

Concurrence: Thomas, joined by Scalia

Dissent: Stevens, joined by Ginsburg, and Breyer

Dissent: Souter, joined by Ginsburg, and Breyer

JUSTICE O’CONNOR announced the judgment of the Court and delivered an opinion, in which THE CHIEF JUSTICE and JUSTICE KENNEDY join.

This is the latest in a series of appeals involving racial gerrymandering challenges to state redistricting efforts in the wake of the 1990 census … That census revealed a population increase, largely in urban minority populations, that entitled Texas to three additional congressional seats. In response, and with a view to complying with the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA), 79 Stat. 437, as amended, 42 U. S. C. § 1973 et seq., the Texas Legislature promulgated a redistricting plan that, among other things, created District 30, a new majority-African-American district in Dallas County; created District 29, a new majority-Hispanic district in and around Houston in Harris County; and reconfigured District 18, which is adjacent to District 29, to make it a majority- African-American district. The Department of Justice precleared that plan under VRA § 5 in 1991, and it was used in the 1992 congressional elections …

The plaintiffs, six Texas voters, challenged the plan, alleging that 24 of Texas’ 30 congressional districts constitute racial gerrymanders in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment. The three-judge United States District Court for the Southern District of Texas held Districts 18, 29, and 30 unconstitutional …

We must now determine whether those districts are subject to strict scrutiny. Our precedents have used a variety of formulations to describe the threshold for the application of strict scrutiny. Strict scrutiny applies where “redistricting legislation … is so extremely irregular on its face that it rationally can be viewed only as an effort to segregate the races for purposes of voting, without regard for traditional districting principles,” Shaw I, …

Strict scrutiny does not apply merely because redistricting is performed with consciousness of race. Nor does it apply to all cases of intentional creation of majority-minority districts … For strict scrutiny to apply, the plaintiffs must prove that other, legitimate districting principles were “subordinated” to race. Miller (1995). By that, we mean that race must be “the predominant factor motivating the legislature’s [redistricting] decision.” Ibid. (emphasis added) …

The present suit is a mixed motive suit. The appellants concede that one of Texas’ goals in creating the three districts at issue was to produce majority-minority districts, but they also cite evidence that other goals, particularly incumbency protection also played a role in the drawing of the district lines … A careful review is, therefore, necessary to determine whether these districts are subject to strict scrutiny …

We begin with general findings and evidence regarding the redistricting plan’s respect for traditional districting principles, the legislators’ expressed motivations, and the methods used in the redistricting process …

These findings-that the State substantially neglected traditional districting criteria such as compactness, that it was committed from the outset to creating majority-minority districts, and that it manipulated district lines to exploit unprecedentedly detailed racial data-together weigh in favor of the application of strict scrutiny. We do not hold that any one of these factors is independently sufficient to require strict scrutiny. The Constitution does not mandate regularity of district shape, see Shaw I (1993), and the neglect of traditional districting criteria is merely necessary, not sufficient. For strict scrutiny to apply, traditional districting criteria must be subordinated to race. Miller (1995). Nor, as we have emphasized, is the decision to create a majority-minority district objectionable in and of itself.

…

Strict scrutiny would not be appropriate if race-neutral, traditional districting considerations predominated over racial ones. We have not subjected political gerrymandering to strict scrutiny … And we have recognized incumbency protection, at least in the limited form of “avoiding contests between incumbent[s],” as a legitimate state goal … Because it is clear that race was not the only factor that motivated the legislature to draw irregular district lines, we must scrutinize each challenged district to determine whether the District Court’s conclusion that race predominated over legitimate districting considerations, including incumbency, can be sustained.

[The Court determines that strict scrutiny applies for Districts 18, 29 and 30.]

Having concluded that strict scrutiny applies, we must determine whether the racial classifications embodied in any of the three districts are narrowly tailored to further a compelling state interest. Appellants point to three compelling interests: the interest in avoiding liability under the “results” test of VRA § 2(b), the interest in remedying past and present racial discrimination, and the “non retrogression” principle of VRA § 5 (for District 18 only) …

A State’s interest in remedying discrimination is compelling when two conditions are satisfied. First, the discrimination that the State seeks to remedy must be specific, “identified discrimination”; second, the State “must have had a ‘strong basis in evidence’ to conclude that remedial action was necessary, ‘before it embarks on an affirmative action program.'” Shaw II, ante, at 910 (citations omitted). Here, the only current problem that appellants cite as in need of remediation is alleged vote dilution as a consequence of racial bloc voting, the same concern that underlies their VRA § 2 compliance defense, which we have assumed to be valid for purposes of this opinion. We have indicated that such problems will not justify race-based districting unless “the State employ[s] sound districting principles, and.., the affected racial group’s residential patterns afford the opportunity of creating districts in which they will be in the majority.” Shaw I (1993), (internal quotation marks omitted). Once that standard is applied, our agreement with the District Court’s finding that these districts are not narrowly tailored to comply with § 2 forecloses this line of defense …

Our legitimacy requires, above all, that we adhere to stare decisis, especially in such sensitive political contexts as the present, where partisan controversy abounds. Legislators and district courts nationwide have modified their practices-or, rather, reembraced the traditional districting practices that were almost universally followed before the 1990 census-in response to Shaw I. Those practices and our precedents, which acknowledge voters as more than mere racial statistics, play an important role in defining the political identity of the American voter. Our Fourteenth Amendment jurisprudence evinces a commitment to eliminate unnecessary and excessive governmental use and reinforcement of racial stereotypes …

We decline to retreat from that commitment today.

The judgment of the District Court is

Affirmed.

Cooper v. Harris (2016)

532 U.S. 234 (2016)

Vote: 5-3

Decision: Affirmed

Majority: Kagan, joined by Thomas, Ginsburg, Breyer, and Sotomayor

Concurrence: Thomas

Dissent: Alito, joined by Roberts, and Kennedy

JUSTICE KAGAN delivered the opinion of the Court.

The Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment limits racial gerrymanders in legislative districting plans. It prevents a State, in the absence of “sufficient justification,” from “separating its citizens into different voting districts on the basis of race.” …

When a voter sues state officials for drawing such race-based lines, our decisions call for a two-step analysis …

First, the plaintiff must prove that “race was the predominant factor motivating the legislature’s decision to place a significant number of voters within or without a particular district.” Miller v. Johnson (1995). That entails demonstrating that the legislature “subordinated” other factors—compactness, respect for political subdivisions, partisan advantage, what have you—to “racial considerations.” Ibid. The plaintiff may make the required showing through “direct evidence” of legislative intent, “circumstantial evidence of a district’s shape and demographics,” or a mix of both …

Second, if racial considerations predominated over others, the design of the district must withstand strict scrutiny. See Bethune-Hill (2017). The burden thus shifts to the State to prove that its race-based sorting of voters serves a “compelling interest” and is “narrowly tailored” to that end. Ibid. This Court has long assumed that one compelling interest is complying with operative provisions of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA or Act) …

This case concerns North Carolina’s most recent redrawing of two congressional districts, both of which have long included substantial populations of black voters. In its current incarnation, District 1 is anchored in the northeastern part of the State, with appendages stretching both south and west (the latter into Durham). District 12 begins in the south-central part of the State (where it takes in a large part of Charlotte) and then travels northeast, zig-zagging much of the way to the State’s northern border …

[From the Opinion’s appendix]

(Enacted 2011)

(Enacted 2011)

(Enacted 2011)

With that out of the way, we turn to the merits of this case, beginning (appropriately enough) with District 1. As noted above, the court below found that race furnished the predominant rationale for that district’s redesign. See supra, at 6–7. And it held that the State’s interest in complying with the VRA could not justify that consideration of race. See supra, at 7. We uphold both conclusions.

Uncontested evidence in the record shows that the State’s mapmakers, in considering District 1, purposefully established a racial target: African-Americans should make up no less than a majority of the voting-age population. Senator Rucho and Representative Lewis were not coy in expressing that goal. They repeatedly told their colleagues that District 1 had to be majority-minority, so as to comply with the VRA. During a Senate debate, for example, Rucho explained that District 1 “must include a sufficient number of African-Americans” to make it “a majority black district.” Similarly, Lewis informed the House and Senate redistricting committees that the district must have “a majority black voting age population.” And that objective was communicated in no uncertain terms to the legislators’ consultant. Dr. Hofeller testified multiple times at trial that Rucho and Lewis instructed him “to draw [District 1] with a [BVAP] in excess of 50 percent.” …

Faced with this body of evidence—showing an announced racial target that subordinated other districting criteria and produced boundaries amplifying divisions between blacks and whites—the District Court did not clearly err in finding that race predominated in drawing District 1. Indeed, as all three judges recognized, the court could hardly have concluded anything but …

The more substantial question is whether District 1 can survive the strict scrutiny applied to racial gerrymanders. As noted earlier, we have long assumed that complying with the VRA is a compelling interest. And we have held that race-based districting is narrowly tailored to that objective if a State had “good reasons” for thinking that the Act demanded such steps.

North Carolina argues that District 1 passes muster under that standard: The General Assembly (so says the State) had “good reasons to believe it needed to draw [District 1] as a majority-minority district to avoid Section 2 liability” for vote dilution. We now turn to that defense …

In sum: Although States enjoy leeway to take race-based actions reasonably judged necessary under a proper interpretation of the VRA, that latitude cannot rescue District 1. We by no means “insist that a state legislature, when redistricting, determine precisely what percent minority population [§2 of the VRA] demands.” Ibid. But neither will we approve a racial gerrymander whose necessity is supported by no evidence and whose raison d’être is a legal mistake. Accordingly, we uphold the District Court’s conclusion that North Carolina’s use of race as the predominant factor in designing District 1 does not withstand strict scrutiny.

We now look west to District 12, making its fifth (!) appearance before this Court. This time, the district’s legality turns, and turns solely, on which of two possible reasons predominantly explains its most recent reconfiguration. The plaintiffs contended at trial that the General Assembly chose voters for District 12, as for District 1, because of their race; more particularly, they urged that the Assembly intentionally increased District 12’s BVAP in the name of ensuring preclearance under the VRA’s §5. But North Carolina declined to mount any defense (similar to the one we have just considered for District 1) that §5’s requirements in fact justified race-based changes to District 12—perhaps because §5 could not reasonably be understood to have done so … Instead, the State altogether denied that racial considerations accounted for (or, indeed, played the slightest role in) District 12’s redesign. According to the State’s version of events, Senator Rucho, Representative Lewis, and Dr. Hofeller moved voters in and out of the district as part of a “strictly” political gerrymander, without regard to race. 6 Record 1011. The mapmakers drew their lines, in other words, to “pack” District 12 with Democrats, not African-Americans. After hearing evidence supporting both parties’ accounts, the District Court accepted the plaintiffs …

Getting to the bottom of a dispute like this one poses special challenges for a trial court. In the more usual case alleging a racial gerrymander—where no one has raised a partisanship defense—the court can make real headway by exploring the challenged district’s conformity to traditional districting principles, such as compactness and respect for county lines. In Shaw II, for example, this Court emphasized the “highly irregular” shape of then-District 12 in concluding that race predominated in its design. But such evidence loses much of its value when the State asserts partisanship as a defense, because a bizarre shape—as of the new District 12—can arise from a “political motivation” as well as a racial one. And crucially, political and racial reasons are capable of yielding similar oddities in a district’s boundaries. That is because, of course, “racial identification is highly correlated with political affiliation.” As a result of those redistricting realities, a trial court has a formidable task: It must make “a sensitive inquiry” into all “circumstantial and direct evidence of intent” to assess whether the plaintiffs have managed to disentangle race from politics and prove that the former drove a district’s lines …

Our job is different—and generally easier. As described earlier, we review a district court’s finding as to racial predominance only for clear error, except when the court made a legal mistake. Under that standard of review, we affirm the court’s finding so long as it is “plausible”; we reverse only when “left with the definite and firm conviction that a mistake has been committed.” And in deciding which side of that line to come down on, we give singular deference to a trial court’s judgments about the credibility of witnesses. That is proper, we have explained, because the various cues that “bear so heavily on the listener’s understanding of and belief in what is said” are lost on an appellate court later sifting through a paper record …

In light of those principles, we uphold the District Court’s finding of racial predominance respecting District 12. The evidence offered at trial, including live witness testimony subject to credibility determinations, adequately supports the conclusion that race, not politics, accounted for the district’s reconfiguration. And no error of law infected that judgment: Contrary to North Carolina’s view, the District Court had no call to dismiss this challenge just because the plaintiffs did not proffer an alternative design for District 12 as circumstantial evidence of the legislature’s intent …

The State mounts a final, legal rather than factual, attack on the District Court’s finding of racial predominance. When race and politics are competing explanations of a district’s lines, argues North Carolina, the party challenging the district must introduce a particular kind of circumstantial evidence: “an alternative [map] that achieves the legislature’s political objectives while improving racial balance.” Brief for Appellants 31 (emphasis deleted). That is true, the State says, irrespective of what other evidence is in the case—so even if the plaintiff offers powerful direct proof that the legislature adopted the map it did for racial reasons. Because the plaintiffs here (as all agree) did not present such a counter-map, North Carolina concludes that they cannot prevail. The dissent echoes that argument …

We have no doubt that an alternative districting plan, of the kind North Carolina describes, can serve as key evidence in a race-versus-politics dispute. One, often highly persuasive way to disprove a State’s contention that politics drove a district’s lines is to show that the legislature had the capacity to accomplish all its partisan goals without moving so many members of a minority group into the district. If you were really sorting by political behavior instead of skin color (so the argument goes) you would have done—or, at least, could just as well have done—this. Such would-have, could-have, and (to round out the set) should-have arguments are a familiar means of undermining a claim that an action was based on a permissible, rather than a prohibited, ground …

But they are hardly the only means. Suppose that the plaintiff in a dispute like this one introduced scores of leaked emails from state officials instructing their mapmaker to pack as many black voters as possible into a district, or telling him to make sure its BVAP hit 75%. Based on such evidence, a court could find that racial rather than political factors predominated in a district’s design, with or without an alternative map. And so too in cases lacking that kind of smoking gun, as long as the evidence offered satisfies the plaintiff ’s burden of proof. In Bush v. Vera, for example, this Court upheld a finding of racial predominance based on “substantial direct evidence of the legislature’s racial motivations”—including credible testimony from political figures and statements made in a §5 preclearance submission—plus circumstantial evidence that redistricters had access to racial, but not political, data at the “block-by-block level” needed to explain their “intricate” designs. See 517 U. S., at 960–963 (plurality opinion). Not a single Member of the Court thought that the absence of a counter-map made any difference. Similarly, it does not matter in this case, where the plaintiffs’ introduction of mostly direct and some circumstantial evidence—documents issued in the redistricting process, testimony of government officials, expert analysis of demographic patterns—gave the District Court a sufficient basis, sans any map, to resolve the race-or-politics question …

North Carolina insists, however, that we have already said to the contrary—more particularly, that our decision in Cromartie II imposed a non-negotiable “alternative-map requirement.”

According to North Carolina, that passage [in Cromartie II] alone settles this case, because it makes an alternative map “essential” to a finding that District 12 (a majority-minority district in which race and partisanship are correlated) was a racial gerrymander. Reply Brief 11. Once again, the dissent says the same.

But the reasoning of Cromartie II belies that reading. The Court’s opinion nowhere attempts to explicate or justify the categorical rule that the State claims to find there. (Certainly, the dissent’s current defense of that rule was nowhere in evidence.) And given the strangeness of that rule—which would treat a mere form of evidence as the very substance of a constitutional claim—we cannot think that the Court adopted it without any explanation. Still more, the entire thrust of the Cromartie II opinion runs counter to an inflexible counter-map requirement. If the Court had adopted that rule, it would have had no need to weigh each piece of evidence in the case and determine whether, taken together, they were “adequate” to show “the predominance of race in the legislature’s line-drawing process.” 532 U. S., at 243–244. But that is exactly what Cromartie II did, over a span of 20 pages and in exhaustive detail. Item by item, the Court discussed and dismantled the supposed proof, both direct and circumstantial, of race-based redistricting. All that careful analysis would have been superfluous—that dogged effort wasted—if the Court viewed the absence or inadequacy of a single form of evidence as necessarily dooming a gerrymandering claim …

In a case like Cromartie II—that is, one in which the plaintiffs had meager direct evidence of a racial gerrymander and needed to rely on evidence of forgone alternatives—only maps of that kind could carry the day. But this case is most unlike Cromartie II, even though it involves the same electoral district some twenty years on. This case turned not on the possibility of creating more optimally constructed districts, but on direct evidence of the General Assembly’s intent in creating the actual District 12, including many hours of trial testimony subject to credibility determinations. That evidence, the District Court plausibly found, itself satisfied the plaintiffs’ burden of debunking North Carolina’s “it was really politics” defense; there was no need for an alternative map to do the same job. And we pay our precedents no respect when we extend them far beyond the circumstances for which they were designed …

Applying a clear error standard, we uphold the District Court’s conclusions that racial considerations predominated in designing both District 1 and District 12. For District 12, that is all we must do, because North Carolina has made no attempt to justify race-based districting there. For District 1, we further uphold the District Court’s decision that §2 of the VRA gave North Carolina no good reason to reshuffle voters because of their race. We accordingly affirm the judgment of the District Court.

It is so ordered.