Religious Freedoms

A New Era?

Burwell v. Hobby Lobby (2013)

573 U.S. 682 (2013)

Vote: 5-4

Decision: Reversed

Majority: Alito, joined by Roberts, Scalia, Kennedy, Thomas

Concurrence: Kennedy

Dissent: Ginsburg, joined by Sotomayor, Breyer, Kagan

Dissent: Breyer, joined by Kagan

[Disclaimer that the case is not a constitutional issue. The excerpt is included because it provides a key building block to the current religious freedom jurisprudence.]

…

JUSTICE ALITO delivered the opinion of the Court.

We must decide in these cases whether the Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993 (RFRA), 107 Stat. 1488, 42 U. S. C. §2000bb et seq., permits the United States Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to demand that three closely held corporations provide health-insurance coverage for methods of contraception that violate the sincerely held religious beliefs of the companies’ owners. We hold that the regulations that impose this obligation violate RFRA, which prohibits the Federal Government from taking any action that substantially burdens the exercise of religion unless that action constitutes the least restrictive means of serving a compelling government interest …

In holding that the HHS mandate is unlawful, we reject HHS’s argument that the owners of the companies forfeited all RFRA protection when they decided to organize their businesses as corporations rather than sole proprietorships or general partnerships. The plain terms of RFRA make it perfectly clear that Congress did not discriminate in this way against men and women who wish to run their businesses as for-profit corporations in the manner required by their religious beliefs. Since RFRA applies in these cases, we must decide whether the challenged HHS regulations substantially burden the exercise of religion, and we hold that they do. The owners of the businesses have religious objections to abortion, and according to their religious beliefs the four contraceptive methods at issue are abortifacients. If the owners comply with the HHS mandate, they believe they will be facilitating abortions, and if they do not comply, they will pay a very heavy price—as much as $1.3 million per day, or about $475 million per year, in the case of one of the companies. If these consequences do not amount to a substantial burden, it is hard to see what would. Under RFRA, a Government action that imposes a substantial burden on religious exercise must serve a compelling government interest, and we assume that the HHS regulations satisfy this requirement. But in order for the HHS mandate to be sustained, it must also constitute the least restrictive means of serving that interest, and the mandate plainly fails that test. There are other ways in which Congress or HHS could equally ensure that every woman has cost-free access to the particular contraceptives at issue here and, indeed, to all FDA-approved contraceptives …

Because RFRA applies in these cases, we must next ask whether the HHS contraceptive mandate “substantially burden[s]” the exercise of religion. 42 U. S. C. §2000bb– 1(a). We have little trouble concluding that it does.

As we have noted, the Hahns and Greens have a sincere religious belief that life begins at conception. They therefore object on religious grounds to providing health insurance that covers methods of birth control that, as HHS acknowledges, see Brief for HHS in No. 13–354, at 9, n. 4, may result in the destruction of an embryo. By requiring the Hahns and Greens and their companies to arrange for such coverage, the HHS mandate demands that they engage in conduct that seriously violates their religious beliefs. If the Hahns and Greens and their companies do not yield to this demand, the economic consequences will be severe …

The least-restrictive-means standard is exceptionally demanding and it is not satisfied here. HHS has not shown that it lacks other means of achieving its desired goal without imposing a substantial burden on the exercise of religion by the objecting parties in these cases … The contraceptive mandate, as applied to closely held corporations, violates RFRA. Our decision on that statutory question makes it unnecessary to reach the First Amendment claim raised by Conestoga and the Hahns.

The judgment of the Tenth Circuit in No. 13–354 is affirmed; the judgment of the Third Circuit in No. 13–356 is reversed, and that case is remanded for further proceedings consistent with this opinion.

It is so ordered.

Masterpiece Cakeshop v. CO (2018)

584 U.S. ___ (2018)

Vote: 7-2

Decision: Reversed

Majority: Kennedy, joined by Roberts, Breyer, Alito, Kagan, Gorsuch

Concurrence: Kagan, joined by Breyer

Concurrence: Gorsuch, joined by Alito

Concurrence: Thomas, joined by Gorsuch

Dissent: Ginsburg, joined by Sotomayor

JUSTICE KENNEDY delivered the opinion of the Court.

In 2012 a same-sex couple visited Masterpiece Cakeshop, a bakery in Colorado, to make inquiries about ordering a cake for their wedding reception. The shop’s owner told the couple that he would not create a cake for their wedding because of his religious opposition to same sex marriages—marriages the State of Colorado itself did not recognize at that time. The couple filed a charge with the Colorado Civil Rights Commission alleging discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation in violation of the Colorado Anti-Discrimination Act.

The Commission determined that the shop’s actions violated the Act and ruled in the couple’s favor. The Colorado state courts affirmed the ruling and its enforcement order, and this Court now must decide whether the Commission’s order violated the Constitution.

The case presents difficult questions as to the proper reconciliation of at least two principles. The first is the authority of a State and its governmental entities to protect the rights and dignity of gay persons who are, or wish to be, married but who face discrimination when they seek goods or services. The second is the right of all persons to exercise fundamental freedoms under the First Amendment, as applied to the States through the Fourteenth Amendment …

Today, the Colorado Anti-Discrimination Act (CADA) carries forward the state’s tradition of prohibiting discrimination in places of public accommodation. Amended in 2007 and 2008 to prohibit discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation as well as other protected characteristics, CADA in relevant part provides as follows: “It is a discriminatory practice and unlawful for a person, directly or indirectly, to refuse, withhold from, or deny to an individual or a group, because of disability, race, creed, color, sex, sexual orientation, marital status, national origin, or ancestry, the full and equal enjoyment of the goods, services, facilities, privileges, advantages, or accommodations of a place of public accommodation.” Colo. Rev. Stat. §24–34–601(2)(a) (2017). The Act defines “public accommodation” broadly to include any “place of business engaged in any sales to the public and any place offering services … to the public,” but excludes “a church, synagogue, mosque, or other place that is principally used for religious purposes …”

Our society has come to the recognition that gay persons and gay couples cannot be treated as social outcasts or as inferior in dignity and worth. For that reason, the laws and the Constitution can, and in some instances must, protect them in the exercise of their civil rights. The exercise of their freedom on terms equal to others must be given great weight and respect by the courts. At the same time, the religious and philosophical objections to gay marriage are protected views and, in some instances, protected forms of expression …

As this Court observed in Obergefell v. Hodges (2015), “[t]he First Amendment ensures that religious organizations and persons are given proper protection as they seek to teach the principles that are so fulfilling and so central to their lives and faiths.” Nevertheless, while those religious and philosophical objections are protected, it is a general rule that such objections do not allow business owners and other actors in the economy and in society to deny protected persons equal access to goods and services under a neutral and generally applicable public accommodations law …

It is unexceptional that Colorado law can protect gay persons, just as it can protect other classes of individuals, in acquiring whatever products and services they choose on the same terms and conditions as are offered to other members of the public. And there are no doubt innumerable goods and services that no one could argue implicate the First Amendment. Petitioners conceded, moreover, that if a baker refused to sell any goods or any cakes for gay weddings, that would be a different matter and the State would have a strong case under this Court’s precedents that this would be a denial of goods and services that went beyond any protected rights of a baker who offers goods and services to the general public and is subject to a neutrally applied and generally applicable public accommodations law.

Phillips claims, however, that a narrower issue is presented. He argues that he had to use his artistic skills to make an expressive statement, a wedding endorsement in his own voice and of his own creation. As Phillips would see the case, this contention has a significant First Amendment speech component and implicates his deep and sincere religious beliefs. In this context the baker likely found it difficult to find a line where the customers’ rights to goods and services became a demand for him to exercise the right of his own personal expression for their message, a message he could not express in a way consistent with his religious beliefs.

Phillips’ dilemma was particularly understandable given the background of legal principles and administration of the law in Colorado at that time … At that point, Colorado did not recognize the validity of gay marriages performed in its own State. At the time of the events in question, this Court had not issued its decisions either in United States v. Windsor (2013), or Obergefell …

At the time, state law also afforded storekeepers some latitude to decline to create specific messages the storekeeper considered offensive. Indeed, while enforcement proceedings against Phillips were ongoing, the Colorado Civil Rights Division itself endorsed this proposition in cases involving other bakers’ creation of cakes, concluding on at least three occasions that a baker acted lawfully in declining to create cakes with decorations that demeaned gay persons or gay marriages.

… But, nonetheless, Phillips was entitled to the neutral and respectful consideration of his claims in all the circumstances of the case.

The neutral and respectful consideration to which Phillips was entitled was compromised here, however. The Civil Rights Commission’s treatment of his case has some elements of a clear and impermissible hostility toward the sincere religious beliefs that motivated his objection. That hostility surfaced at the Commission’s formal, public hearings, as shown by the record … [T]hese statements are susceptible of different interpretations. On the one hand, they might mean simply that a business cannot refuse to provide services based on sexual orientation, regardless of the proprietor’s personal views. On the other hand, they might be seen as inappropriate and dismissive comments showing lack of due consideration for Phillips’ free exercise rights and the dilemma he faced. In view of the comments that followed, the latter seems the more likely …

For the reasons just described, the Commission’s treatment of Phillips’ case violated the State’s duty under the First Amendment not to base laws or regulations on hostility to a religion or religious viewpoint. In Church of Lukumi Babalu Aye, the Court made clear that the government, if it is to respect the Constitution’s guarantee of free exercise, cannot impose regulations that are hostile to the religious beliefs of affected citizens and cannot act in a manner that passes judgment upon or presupposes the illegitimacy of religious beliefs and practices. The Free Exercise Clause bars even “subtle departures from neutrality” on matters of religion. Here, that means the Commission was obliged under the Free Exercise Clause to proceed in a manner neutral toward and tolerant of Phillips’ religious beliefs. The Constitution “commits government itself to religious tolerance, and upon even slight suspicion that proposals for state intervention stem from animosity to religion or distrust of its practices, all officials must pause to remember their own high duty to the Constitution and to the rights it secures …”

While the issues here are difficult to resolve, it must be concluded that the State’s interest could have been weighed against Phillips’ sincere religious objections in a way consistent with the requisite religious neutrality that must be strictly observed. The official expressions of hostility to religion in some of the commissioners’ comments—comments that were not disavowed at the Commission or by the State at any point in the proceedings that led to affirmance of the order—were inconsistent with what the Free Exercise Clause requires. The Commission’s disparate consideration of Phillips’ case compared to the cases of the other bakers suggests the same. For these reasons, the order must be set aside …

The Commission’s hostility was inconsistent with the First Amendment’s guarantee that our laws be applied in a manner that is neutral toward religion. Phillips was entitled to a neutral decisionmaker who would give full and fair consideration to his religious objection as he sought to assert it in all of the circumstances in which this case was presented, considered, and decided. In this case the adjudication concerned a context that may well be different going forward in the respects noted above. However later cases raising these or similar concerns are resolved in the future, for these reasons the rulings of the Commission and of the state court that enforced the Commission’s order must be invalidated.

The outcome of cases like this in other circumstances must await further elaboration in the courts, all in the context of recognizing that these disputes must be resolved with tolerance, without undue disrespect to sincere religious beliefs, and without subjecting gay persons to indignities when they seek goods and services in an open market. The judgment of the Colorado Court of Appeals is reversed.

It is so ordered.

Tandon v. Newsom (2021)

593 U.S. ___ (2021)

Vote: 6-3

Per Curiam Opinion

Decision: Reversed

Dissent: Kagan, joined by Breyer, Sotomayor

PER CURIAM.

The Ninth Circuit’s failure to grant an injunction pending appeal was erroneous. This Court’s decisions have made the following points clear.

First, government regulations are not neutral and generally applicable, and therefore trigger strict scrutiny under the Free Exercise Clause, whenever they treat any comparable secular activity more favorably than religious exercise. It is no answer that a State treats some comparable secular businesses or other activities as poorly as or even less favorably than the religious exercise at issue …

Second, whether two activities are comparable for purposes of the Free Exercise Clause must be judged against the asserted government interest that justifies the regulation at issue. Comparability is concerned with the risks various activities pose, not the reasons why people gather …

Third, the government has the burden to establish that the challenged law satisfies strict scrutiny. To do so in this context, it must do more than assert that certain risk factors “are always present in worship, or always absent from the other secular activities” the government may allow … Instead, narrow tailoring requires the government to show that measures less restrictive of the First Amendment activity could not address its interest in reducing the spread of COVID. Where the government permits other activities to proceed with precautions, it must show that the religious exercise at issue is more dangerous than those activities even when the same precautions are applied. Otherwise, precautions that suffice for other activities suffice for religious exercise too …

Fourth, even if the government withdraws or modifies a COVID restriction in the course of litigation, that does not necessarily moot the case. And so long as a case is not moot, litigants otherwise entitled to emergency injunctive relief remain entitled to such relief where the applicants “remain under a constant threat” that government officials will use their power to reinstate the challenged restrictions …

Applicants are likely to succeed on the merits of their free exercise claim; they are irreparably harmed by the loss of free exercise rights “for even minimal periods of time”; and the State has not shown that “public health would be imperiled” by employing less restrictive measures. Accordingly, applicants are entitled to an injunction pending appeal …

This is the fifth time the Court has summarily rejected the Ninth Circuit’s analysis of California’s COVID restrictions on religious exercise …

It is unsurprising that such litigants are entitled to relief. California’s Blueprint System contains myriad exceptions and accommodations for comparable activities, thus requiring the application of strict scrutiny. And historically, strict scrutiny requires the State to further “interests of the highest order” by means “narrowly tailored in pursuit of those interests …”

…

JUSTICE KAGAN, with whom JUSTICE BREYER and JUSTICE SOTOMAYOR join, dissenting.

I would deny the application largely for the reasons stated in South Bay United Pentecostal Church v. Newsom, (KAGAN, J., dissenting). The First Amendment requires that a State treat religious conduct as well as the State treats comparable secular conduct. Sometimes finding the right secular analogue may raise hard questions. But not today. California limits religious gatherings in homes to three households. If the State also limits all secular gatherings in homes to three households, it has complied with the First Amendment. And the State does exactly that: It has adopted a blanket restriction on at home gatherings of all kinds, religious and secular alike. California need not, as the per curiam insists, treat at-home religious gatherings the same as hardware stores and hair salons—and thus unlike at-home secular gatherings, the obvious comparator here. As the per curiam’s reliance on separate opinions and unreasoned orders signals, the law does not require that the State equally treat apples and watermelons …

First, “when people gather in social settings, their interactions are likely to be longer than they would be in a commercial setting,” with participants “more likely to be involved in prolonged conversations.” Tandon v. Newsom (2021). Second, “private houses are typically smaller and less ventilated than commercial establishments.” Ibid. And third, “social distancing and mask-wearing are less likely in private settings and enforcement is more difficult.” Ibid. These are not the mere musings of two appellate judges: The district court found each of these facts based on the uncontested testimony of California’s public-health experts … No doubt this evidence is inconvenient for the per curiam’s preferred result. But the Court has no warrant to ignore the record in a case that (on its own view, see ante, at 2) turns on risk assessments. In ordering California to weaken its restrictions on at home gatherings, the majority yet again “insists on treating unlike cases, not like ones, equivalently …” And it once more commands California “to ignore its experts’ scientific findings,” thus impairing “the State’s effort to address a public health emergency.” Ibid. Because the majority continues to disregard law and facts alike, I respectfully dissent from this latest per curiam decision …

Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue (2020)

91 U.S. ___ (2020)

Vote: 5-4

Decision: Reversed

Majority: Roberts, joined by Thomas, Alito, Gorsuch, Kavanaugh

Concurrence: Thomas, joined by Gorsuch

Concurrence: Alito

Concurrence: Gorsuch

Dissent: Ginsburg, joined by Kagan

Dissent: Breyer, joined by Kagan

Dissent: Sotomayor

CHIEF JUSTICE ROBERTS delivered the opinion of the Court.

…

The Montana Legislature established a program to provide tuition assistance to parents who send their children to private schools. The program grants a tax credit to anyone who donates to certain organizations that in turn award scholarships to selected students attending such schools. When petitioners sought to use the scholarships at a religious school, the Montana Supreme Court struck down the program. The Court relied on the “no-aid” provision of the State Constitution, which prohibits any aid to a school controlled by a “church, sect, or denomination.” The question presented is whether the Free Exercise Clause of the United States Constitution barred that application of the no-aid provision …

This suit was brought by three mothers whose children attend Stillwater Christian School in northwestern Montana. Stillwater is a private Christian school that meets the statutory criteria for “qualified education providers.” It serves students in prekindergarten through 12th grade, and petitioners chose the school in large part because it “teaches the same Christian values that [they] teach at home.” The child of one petitioner has already received scholarships from Big Sky, and the other petitioners’ children are eligible for scholarships and planned to apply. While in effect, however, Rule 1 blocked petitioners from using scholarship funds for tuition at Stillwater. To overcome that obstacle, petitioners sued the Department of Revenue in Montana state court. Petitioners claimed that Rule 1 conflicted with the statute that created the scholarship program and could not be justified on the ground that it was compelled by the Montana Constitution’s no-aid provision. Petitioners further alleged that the Rule discriminated on the basis of their religious views and the religious nature of the school they had chosen for their children …

The question for this Court is whether the Free Exercise Clause precluded the Montana Supreme Court from applying Montana’s no-aid provision to bar religious schools from the scholarship program. For purposes of answering that question, we accept the Montana Supreme Court’s interpretation of state law—including its determination that the scholarship program provided impermissible “aid” within the meaning of the Montana Constitution—and we assess whether excluding religious schools and affected families from that program was consistent with the Federal Constitution …

The Free Exercise Clause, which applies to the States under the Fourteenth Amendment, “protects religious observers against unequal treatment” and against “laws that impose special disabilities on the basis of religious status.” Trinity Lutheran …

Most recently, Trinity Lutheran distilled these and other decisions to the same effect into the “unremarkable” conclusion that disqualifying otherwise eligible recipients from a public benefit “solely because of their religious character” imposes “a penalty on the free exercise of religion that triggers the most exacting scrutiny.” In Trinity Lutheran, Missouri provided grants to help nonprofit organizations pay for playground resurfacing, but a state policy disqualified any organization “owned or controlled by a church, sect, or other religious entity.” Because of that policy, an otherwise eligible church-owned preschool was denied a grant to resurface its playground. Missouri’s policy discriminated against the Church “simply because of what it is—a church,” and so the policy was subject to the “strictest scrutiny,” which it failed. We acknowledged that the State had not “criminalized” the way in which the Church worshipped or “told the Church that it cannot subscribe to a certain view of the Gospel.” But the State’s discriminatory policy was “odious to our Constitution all the same.”

Here too Montana’s no-aid provision bars religious schools from public benefits solely because of the religious character of the schools. The provision also bars parents who wish to send their children to a religious school from those same benefits, again solely because of the religious character of the school. This is apparent from the plain text. The provision bars aid to any school “controlled in whole or in part by any church, sect, or denomination …” The provision’s title— “Aid prohibited to sectarian schools”—confirms that the provision singles out schools based on their religious character … And the Montana Supreme Court explained that the provision forbids aid to any school that is “sectarian,” “religiously affiliated,” or “controlled in whole or in part by churches …”

This case also turns expressly on religious status and not religious use. The Montana Supreme Court applied the no-aid provision solely by reference to religious status. The Court repeatedly explained that the no-aid provision bars aid to “schools controlled in whole or in part by churches,” “sectarian schools,” and “religiously-affiliated schools.” Applying this provision to the scholarship program, the Montana Supreme Court noted that most of the private schools that would benefit from the program were “religiously affiliated” and “controlled by churches,” and the Court ultimately concluded that the scholarship program ran afoul of the Montana Constitution by aiding “schools controlled by churches.” The Montana Constitution discriminates based on religious status just like the Missouri policy in Trinity Lutheran, which excluded organizations “owned or controlled by a church, sect, or other religious entity.”

…

The Montana Supreme Court asserted that the no-aid provision serves Montana’s interest in separating church and State “more fiercely” than the Federal Constitution. But “that interest cannot qualify as compelling” in the face of the infringement of free exercise here. A State’s interest “in achieving greater separation of church and State than is already ensured under the Establishment Clause … is limited by the Free Exercise Clause …”

The Department, for its part, asserts that the no-aid provision actually promotes religious freedom. In the Department’s view, the no-aid provision protects the religious liberty of taxpayers by ensuring that their taxes are not directed to religious organizations, and it safeguards the freedom of religious organizations by keeping the government out of their operations. An infringement of First Amendment rights, however, cannot be justified by a State’s alternative view that the infringement advances religious liberty. Our federal system prizes state experimentation, but not “state experimentation in the suppression of free speech,” and the same goes for the free exercise of religion …

Furthermore, we do not see how the no-aid provision promotes religious freedom. As noted, this Court has repeatedly upheld government programs that spend taxpayer funds on equal aid to religious observers and organizations, particularly when the link between government and religion is attenuated by private choices. A school, concerned about government involvement with its religious activities, might reasonably decide for itself not to participate in a government program. But we doubt that the school’s liberty is enhanced by eliminating any option to participate in the first place … A State need not subsidize private education. But once a State decides to do so, it cannot disqualify some private schools solely because they are religious …

The Department argues that, at the end of the day, there is no free exercise violation here because the Montana Supreme Court ultimately eliminated the scholarship program altogether. According to the Department, now that there is no program, religious schools and adherents cannot complain that they are excluded from any generally available benefit … The descriptions are not accurate. The Montana Legislature created the scholarship program; the Legislature never chose to end it, for policy or other reasons … [S]eeing no other “mechanism” to make absolutely sure that religious schools received no aid, the court chose to invalidate the entire program.

The final step in this line of reasoning eliminated the program, to the detriment of religious and non-religious schools alike. But the Court’s error of federal law occurred at the beginning. When the Court was called upon to apply a state law no-aid provision to exclude religious schools from the program, it was obligated by the Federal Constitution to reject the invitation. Had the Court recognized that this was, indeed, “one of those cases” in which application of the no-aid provision “would violate the Free Exercise Clause … the Court would not have proceeded to find a violation of that provision. And, in the absence of such a state law violation, the Court would have had no basis for terminating the program. Because the elimination of the program flowed directly from the Montana Supreme Court’s failure to follow the dictates of federal law, it cannot be defended as a neutral policy decision, or as resting on adequate and independent state law grounds.

The Supremacy Clause provides that “the Judges in every State shall be bound” by the Federal Constitution, “any Thing in the Constitution or Laws of any State to the Contrary notwithstanding …” “[T]his Clause creates a rule of decision” directing state courts that they “must not give effect to state laws that conflict with federal law … Given the conflict between the Free Exercise Clause and the application of the no-aid provision here, the Montana Supreme Court should have “disregard[ed]” the no-aid provision and decided this case “conformably to the [C]onstitution” of the United States … That “supreme law of the land” condemns discrimination against religious schools and the families whose children attend them. Id., at 180. They are “member[s] of the community too,” and their exclusion from the scholarship program here is “odious to our Constitution” and “cannot stand …”

* * *

The judgment of the Montana Supreme Court is reversed, and the case is remanded for further proceedings not inconsistent with this opinion.

It is so ordered.

Fulton v. Philadelphia (2021)

593 U.S. ___ (2021)

Vote: 9-0

Decision: Reversed

Majority: Roberts, joined by Breyer, Sotomayor, Kagan, Kavanaugh and Barrett

Concurrence: Barrett, joined by Kavanaugh and Breyer (except for the first paragraph)

Concurrence: Alito, joined by Thomas and Gorsuch

Concurrence: Gorsuch, joined by Thomas and Gorsuch

Chief Justice Roberts delivered the opinion of the Court.

Catholic Social Services is a foster care agency in Philadelphia. The City stopped referring children to CSS upon discovering that the agency would not certify same-sex couples to be foster parents due to its religious beliefs about marriage. The City will renew its foster care contract with CSS only if the agency agrees to certify same-sex couples. The question presented is whether the actions of Philadelphia violate the First Amendment.

The Catholic Church has served the needy children of Philadelphia for over two centuries …

The Philadelphia foster care system depends on cooperation between the City and private foster agencies like CSS. When children cannot remain in their homes, the City’s Department of Human Services assumes custody of them. The Department enters standard annual contracts with private foster agencies to place some of those children with foster families.

The placement process begins with review of prospective foster families. Pennsylvania law gives the authority to certify foster families to state-licensed foster agencies like CSS. 55 Pa. Code §3700.61 (2020) …

When the Department seeks to place a child with a foster family, it sends its contracted agencies a request, known as a referral. The agencies report whether any of their certified families are available, and the Department places the child with what it regards as the most suitable family. The agency continues to support the family throughout the placement.

The religious views of CSS inform its work in this system. CSS believes that “marriage is a sacred bond between a man and a woman.” App. 171. Because the agency understands the certification of prospective foster families to be an endorsement of their relationships, it will not certify unmarried couples—regardless of their sexual orientation—or same-sex married couples. CSS does not object to certifying gay or lesbian individuals as single foster parents or to placing gay and lesbian children. No same-sex couple has ever sought certification from CSS. If one did, CSS would direct the couple to one of the more than 20 other agencies in the City, all of which currently certify same-sex couples. For over 50 years, CSS successfully contracted with the City to provide foster care services while holding to these beliefs.

But things changed in 2018. After receiving a complaint about a different agency, a newspaper ran a story in which a spokesman for the Archdiocese of Philadelphia stated that CSS would not be able to consider prospective foster parents in same-sex marriages. The City Council called for an investigation, saying that the City had “laws in place to protect its people from discrimination that occurs under the guise of religious freedom.” App. to Pet. for Cert. 147a. The Philadelphia Commission on Human Relations launched an inquiry. And the Commissioner of the Department of Human Services held a meeting with the leadership of CSS. She remarked that “things have changed since 100 years ago,” and “it would be great if we followed the teachings of Pope Francis, the voice of the Catholic Church.” App. 366. Immediately after the meeting, the Department informed CSS that it would no longer refer children to the agency. The City later explained that the refusal of CSS to certify same-sex couples violated a non-discrimination provision in its contract with the City as well as the non-discrimination requirements of the citywide Fair Practices Ordinance. The City stated that it would not enter a full foster care contract with CSS in the future unless the agency agreed to certify same-sex couples.

CSS and three foster parents affiliated with the agency filed suit against the City, the Department, and the Commission … As relevant here, CSS alleged that the referral freeze violated the Free Exercise and Free Speech Clauses of the First Amendment … The District Court denied preliminary relief … The court also determined that the free speech claims were unlikely to succeed because CSS performed certifications as part of a government program. Id., at 695–700.

The Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit affirmed. Because the contract between the parties had expired, the court focused on whether the City could insist on the inclusion of new language forbidding discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation as a condition of contract renewal. The court concluded that the proposed contractual terms were a neutral and generally applicable policy under Smith. The court rejected the agency’s free speech claims on the same grounds as the District Court.

CSS and the foster parents sought review. They challenged the Third Circuit’s determination that the City’s actions were permissible under Smith and also asked this Court to reconsider that precedent.

We granted certiorari.

As an initial matter, it is plain that the City’s actions have burdened CSS’s religious exercise by putting it to the choice of curtailing its mission or approving relationships inconsistent with its beliefs. The City disagrees. In its view, certification reflects only that foster parents satisfy the statutory criteria, not that the agency endorses their relationships. But CSS believes that certification is tantamount to endorsement. And “religious beliefs need not be acceptable, logical, consistent, or comprehensible to others in order to merit First Amendment protection.” Thomas v. Review Bd. of Ind. Employment Security Div. Our task is to decide whether the burden the City has placed on the religious exercise of CSS is constitutionally permissible.

Smith held that laws incidentally burdening religion are ordinarily not subject to strict scrutiny under the Free Exercise Clause so long as they are neutral and generally applicable. CSS urges us to overrule Smith, and the concurrences in the judgment argue in favor of doing so, see post, p. 1 (opinion of Alito, J.); post, p. 1 (opinion of Gorsuch, J.). But we need not revisit that decision here. This case falls outside Smith because the City has burdened the religious exercise of CSS through policies that do not meet the requirement of being neutral and generally applicable.

Government fails to act neutrally when it proceeds in a manner intolerant of religious beliefs or restricts practices because of their religious nature. See Masterpiece Cakeshop, Ltd. v. Colorado Civil Rights Comm’n …

A law is not generally applicable if it “invite[s]” the government to consider the particular reasons for a person’s conduct by providing “ ‘a mechanism for individualized exemptions.’ ” Smith … Smith later explained that the unemployment benefits law in Sherbert was not generally applicable because the “good cause” standard permitted the government to grant exemptions based on the circumstances underlying each application. Smith went on to hold that “where the State has in place a system of individual exemptions, it may not refuse to extend that system to cases of ‘religious hardship’ without compelling reason.”

A law also lacks general applicability if it prohibits religious conduct while permitting secular conduct that undermines the government’s asserted interests in a similar way … In Church of Lukumi Babalu Aye, Inc. v. Hialeah, for instance, the City of Hialeah adopted several ordinances prohibiting animal sacrifice, a practice of the Santeria faith. Id., at 524–528. The City claimed that the ordinances were necessary in part to protect public health, which was “threatened by the disposal of animal carcasses in open public places.” But the ordinances did not regulate hunters’ disposal of their kills or improper garbage disposal by restaurants, both of which posed a similar hazard. The Court concluded that this and other forms of underinclusiveness meant that the ordinances were not generally applicable …

The City initially argued that CSS’s practice violated section 3.21 of its standard foster care contract. We conclude, however, that this provision is not generally applicable as required by Smith …

Like the good cause provision in Sherbert, section 3.21 incorporates a system of individual exemptions, made available in this case at the “sole discretion” of the Commissioner. The City has made clear that the Commissioner “has no intention of granting an exception” to CSS …

… We have never suggested that the government may discriminate against religion when acting in its managerial role. And Smith itself drew support for the neutral and generally applicable standard from cases involving internal government affairs …

… The City and intervenor-respondents accordingly ask only that courts apply a more deferential approach in determining whether a policy is neutral and generally applicable in the contracting context. We find no need to resolve that narrow issue in this case. No matter the level of deference we extend to the City, the inclusion of a formal system of entirely discretionary exceptions in section 3.21 renders the contractual non-discrimination requirement not generally applicable …

The City and intervenor-respondents add that, notwithstanding the system of exceptions in section 3.21, a separate provision in the contract independently prohibits discrimination in the certification of foster parents. That provision, section 15.1, bars discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation, and it does not on its face allow for exceptions. But state law makes clear that “one part of a contract cannot be so interpreted as to annul another part.” Applying that “fundamental” rule here, Shehadi, 474 Pa., at 236, 378 A. 2d, at 306, an exception from section 3.21 also must govern the prohibition in section 15.1, lest the City’s reservation of the authority to grant such an exception be a nullity. As a result, the contract as a whole contains no generally applicable non-discrimination requirement.

Finally, the City and intervenor-respondents contend that the availability of exceptions under section 3.21 is irrelevant because the Commissioner has never granted one. That misapprehends the issue. The creation of a formal mechanism for granting exceptions renders a policy not generally applicable, regardless whether any exceptions have been given, because it “invite[s]” the government to decide which reasons for not complying with the policy are worthy of solicitude—here, at the Commissioner’s “sole discretion.”

The contractual non-discrimination requirement imposes a burden on CSS’s religious exercise and does not qualify as generally applicable. The concurrence protests that the “Court granted certiorari to decide whether to overrule [Smith],” and chides the Court for seeking to “sidestep the question.” Post, at 1 (opinion of Gorsuch, J.). But the Court also granted review to decide whether Philadelphia’s actions were permissible under our precedents. See Pet. for Cert. i. CSS has demonstrated that the City’s actions are subject to “the most rigorous of scrutiny” under those precedents. Lukumi. Because the City’s actions are therefore examined under the strictest scrutiny regardless of Smith, we have no occasion to reconsider that decision here.

A government policy can survive strict scrutiny only if it advances “interests of the highest order” and is narrowly tailored to achieve those interests. Lukumi, (internal quotation marks omitted). Put another way, so long as the government can achieve its interests in a manner that does not burden religion, it must do so.

The City asserts that its non-discrimination policies serve three compelling interests: maximizing the number of foster parents, protecting the City from liability, and ensuring equal treatment of prospective foster parents and foster children. The City states these objectives at a high level of generality, but the First Amendment demands a more precise analysis … The question, then, is not whether the City has a compelling interest in enforcing its non-discrimination policies generally, but whether it has such an interest in denying an exception to CSS.

Once properly narrowed, the City’s asserted interests are insufficient. Maximizing the number of foster families and minimizing liability are important goals, but the City fails to show that granting CSS an exception will put those goals at risk. If anything, including CSS in the program seems likely to increase, not reduce, the number of available foster parents. As for liability, the City offers only speculation that it might be sued over CSS’s certification practices. Such speculation is insufficient to satisfy strict scrutiny, particularly because the authority to certify foster families is delegated to agencies by the State, not the City, see 55 Pa. Code §3700.61.

That leaves the interest of the City in the equal treatment of prospective foster parents and foster children. We do not doubt that this interest is a weighty one, for “[o]ur society has come to the recognition that gay persons and gay couples cannot be treated as social outcasts or as inferior in dignity and worth.” Masterpiece Cakeshop, On the facts of this case, however, this interest cannot justify denying CSS an exception for its religious exercise. The creation of a system of exceptions under the contract undermines the City’s contention that its non-discrimination policies can brook no departures. The City offers no compelling reason why it has a particular interest in denying an exception to CSS while making them available to others.

As Philadelphia acknowledges, CSS has “long been a point of light in the City’s foster-care system.” Brief for City Respondents 1. CSS seeks only an accommodation that will allow it to continue serving the children of Philadelphia in a manner consistent with its religious beliefs; it does not seek to impose those beliefs on anyone else. The refusal of Philadelphia to contract with CSS for the provision of foster care services unless it agrees to certify same-sex couples as foster parents cannot survive strict scrutiny, and violates the First Amendment.

In view of our conclusion that the actions of the City violate the Free Exercise Clause, we need not consider whether they also violate the Free Speech Clause.

The judgment of the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit is reversed, and the case is remanded for further proceedings consistent with this opinion.

Kennedy v. Bremerton School District (2022)

597 U.S. ___ (2022)

Vote: 6-3

Decision: Reversed

Majority: Gorsuch, joined by Roberts, Thomas, Alito, Barrett and Kavanaugh (except Part II-B)

Concurrence: Thomas

Concurrence: Alito

Dissent: Sotomayor, joined by Breyer and Kagan

Justice Gorsuch delivered the opinion of the Court.

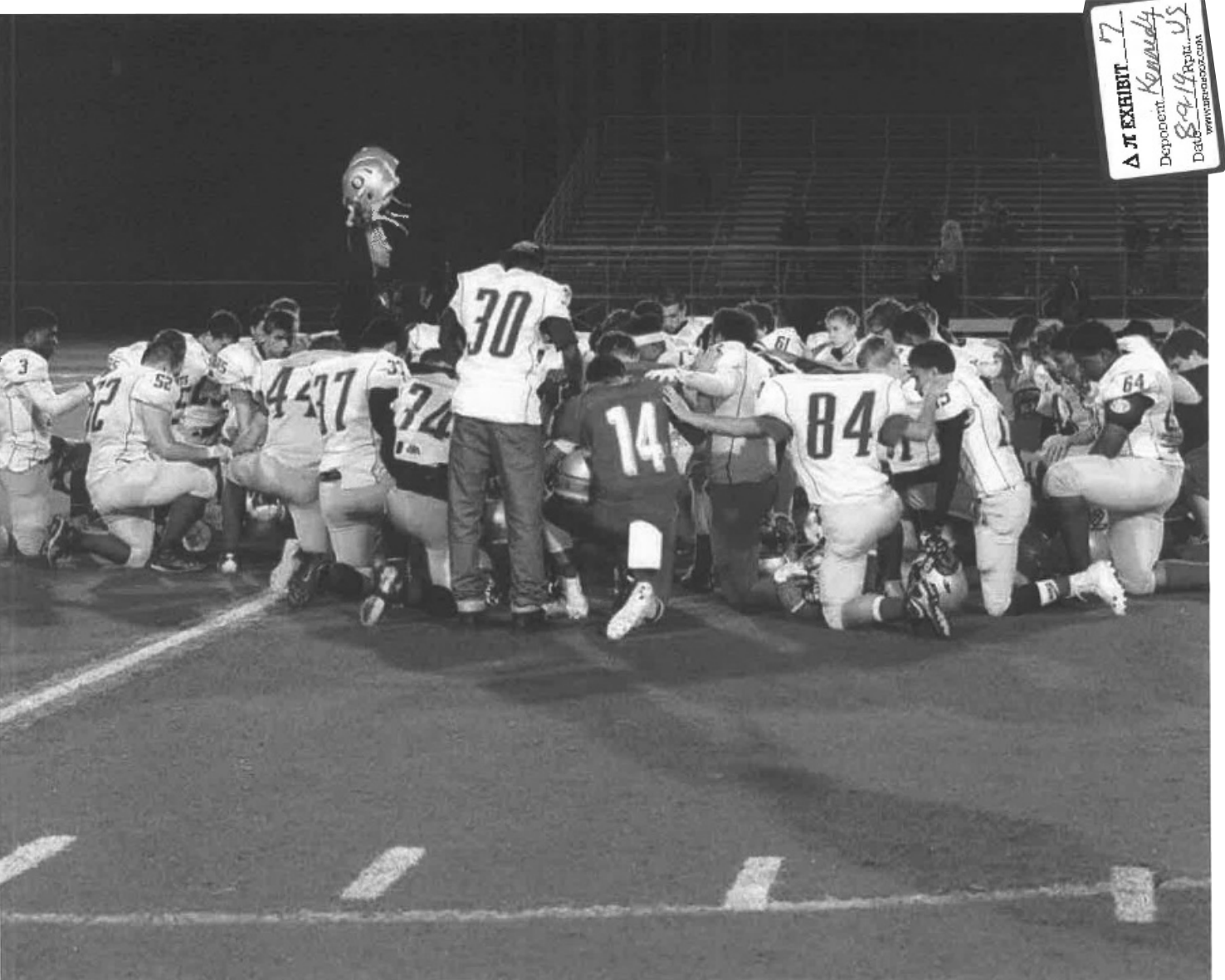

Joseph Kennedy lost his job as a high school football coach because he knelt at midfield after games to offer a quiet prayer of thanks. Mr. Kennedy prayed during a period when school employees were free to speak with a friend, call for a reservation at a restaurant, check email, or attend to other personal matters. He offered his prayers quietly while his students were otherwise occupied. Still, the Bremerton School District disciplined him anyway. It did so because it thought anything less could lead a reasonable observer to conclude (mistakenly) that it endorsed Mr. Kennedy’s religious beliefs. That reasoning was misguided. Both the Free Exercise and Free Speech Clauses of the First Amendment protect expressions like Mr. Kennedy’s. Nor does a proper understanding of the Amendment’s Establishment Clause require the government to single out private religious speech for special disfavor. The Constitution and the best of our traditions counsel mutual respect and tolerance, not censorship and suppression, for religious and nonreligious views alike.

Joseph Kennedy began working as a football coach at Bremerton High School in 2008 after nearly two decades of service in the Marine Corps. App. 167. Like many other football players and coaches across the country, Mr. Kennedy made it a practice to give “thanks through prayer on the playing field” at the conclusion of each game. Id., at 168, 171 … Initially, Mr. Kennedy prayed on his own. See Ibid. But over time, some players asked whether they could pray alongside him. 991 F. 3d 1004, 1010 (CA9 2021); App. 169 … The number of players who joined Mr. Kennedy eventually grew to include most of the team, at least after some games. Sometimes team members invited opposing players to join … Eventually, Mr. Kennedy began incorporating short motivational speeches with his prayer when others were present. See id., at 170 … Mr. Kennedy explained that he “never told any student that it was important they participate in any religious activity.” Ibid. In particular, he “never pressured or encouraged any student to join” his postgame midfield prayers. Ibid.

… It seems the District’s superintendent first learned of [the prayers] only in September 2015 … At that point, the District reacted quickly … The District explained that it sought to establish “clear parameters” “going forward.” Ibid. It instructed Mr. Kennedy to avoid any motivational “talks with students” that “include[d] religious expression, including prayer,” and to avoid “suggest[ing], encourag[ing] (or discourag[ing]), or supervis[ing]” any prayers of students, which students remained free to “engage in.” Id., at 44. The District also explained that any religious activity on Mr. Kennedy’s part must be “nondemonstrative (i.e., not outwardly discernible as religious activity)” if “students are also engaged in religious conduct” in order to “avoid the perception of endorsement.” Id., at 45. In offering these directives, the District appealed to what it called a “direct tension between” the “Establishment Clause” and “a school employee’s [right to] free[ly] exercise” his religion. Id., at 43. To resolve that “tension,” the District explained, an employee’s free exercise rights “must yield so far as necessary to avoid school endorsement of religious activities.” Ibid.

… Mr. Kennedy further felt pressured to abandon his practice of saying his own quiet, on-field postgame prayer. See id., at 172. Driving home after a game, however, Mr. Kennedy felt upset that he had “broken [his] commitment to God” by not offering his own prayer, so he turned his car around and returned to the field. Ibid. By that point, everyone had left the stadium, and he walked to the 50-yard line and knelt to say a brief prayer of thanks. See Ibid …

On October 14, through counsel, Mr. Kennedy sent a letter to school officials informing them that, because of his “sincerely-held religious beliefs,” he felt “compelled” to offer a “post-game personal prayer” of thanks at midfield. Id., at 62–63, 172 … Mr. Kennedy emphasized that he sought only the opportunity to “wai[t] until the game is over and the players have left the field and then wal[k] to mid-field to say a short, private, personal prayer.” Id., at 69 …

Yet instead of accommodating Mr. Kennedy’s request to offer a brief prayer on the field while students were busy with other activities—whether heading to the locker room, boarding the bus, or perhaps singing the school fight song— the District issued an ultimatum. It forbade Mr. Kennedy from engaging in “any overt actions” that could “appea[r] to a reasonable observer to endorse … prayer … while he is on duty as a District-paid coach.” Id., at 81 …

After receiving this letter, Mr. Kennedy offered a brief prayer following the October 16 game. See id., at 90. When he bowed his head at midfield after the game, “most [Bremerton] players were … engaged in the traditional singing of the school fight song to the audience.” Ibid. Though Mr. Kennedy was alone when he began to pray, players from the other team and members of the community joined him before he finished his prayer. See id., at 82, 297. This event spurred media coverage of Mr. Kennedy’s dilemma and a public response from the District … Still, the District explained that a “reasonable observer” could think government endorsement of religion had occurred when a “District employee, on the field only by virtue of his employment with the District, still on duty” engaged in “overtly religious conduct.” Id., at 91, 93. The District thus made clear that the only option it would offer Mr. Kennedy was to allow him to pray after a game in a “private location” behind closed doors and “not observable to students or the public.” Id., at 93– 94.

…

Shortly after the October 26 game, the District placed Mr. Kennedy on paid administrative leave and prohibited him from “participat[ing], in any capacity, in … football program activities.” Ibid …

After these events, Mr. Kennedy sued in federal court, alleging that the District’s actions violated the First Amendment’s Free Speech and Free Exercise Clauses … These Clauses work in tandem. Where the Free Exercise Clause protects religious exercises, whether communicative or not, the Free Speech Clause provides overlapping protection for expressive religious activities. That the First Amendment doubly protects religious speech is no accident. It is a natural outgrowth of the framers’ distrust of government attempts to regulate religion and suppress dissent …

Under this Court’s precedents, a plaintiff bears certain burdens to demonstrate an infringement of his rights under the Free Exercise and Free Speech Clauses. If the plaintiff carries these burdens, the focus then shifts to the defendant to show that its actions were nonetheless justified and tailored consistent with the demands of our case law. See, e.g., Fulton v. Philadelphia, (2021) … We begin by examining whether Mr. Kennedy has discharged his burdens, first under the Free Exercise Clause, then under the Free Speech Clause.

The Free Exercise Clause … protects not only the right to harbor religious beliefs inwardly and secretly. It does perhaps its most important work by protecting the ability of those who hold religious beliefs of all kinds to live out their faiths in daily life through “the performance of (or abstention from) physical acts.” Employment Div., Dept. of Human Resources of Ore. v. Smith, (1990).

Under this Court’s precedents, a plaintiff may carry the burden of proving a free exercise violation in various ways, including by showing that a government entity has burdened his sincere religious practice pursuant to a policy that is not “neutral” or “generally applicable.” Id., at 879– 881. Should a plaintiff make a showing like that, this Court will find a First Amendment violation unless the government can satisfy “strict scrutiny” by demonstrating its course was justified by a compelling state interest and was narrowly tailored in pursuit of that interest. Lukumi.

That Mr. Kennedy has discharged his burdens is effectively undisputed. No one questions that he seeks to engage in a sincerely motivated religious exercise … Nor does anyone question that, in forbidding Mr. Kennedy’s brief prayer, the District failed to act pursuant to a neutral and generally applicable rule. A government policy will not qualify as neutral if it is “specifically directed at … religious practice.” Smith … In this case, the District’s challenged policies were neither neutral nor generally applicable. By its own admission, the District sought to restrict Mr. Kennedy’s actions at least in part because of their religious character …

When it comes to Mr. Kennedy’s free speech claim, our precedents remind us that the First Amendment’s protections extend to “teachers and students,” neither of whom “shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.” Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School Dist., (1969) … Of course, none of this means the speech rights of public school employees are so boundless that they may deliver any message to anyone anytime they wish. In addition to being private citizens, teachers and coaches are also government employees paid in part to speak on the government’s behalf and convey its intended messages …

To account for the complexity associated with the interplay between free speech rights and government employment, this Court’s decisions [Pickering v. Board of Ed. of Township High School Dist. (1968), Garcetti] … suggest proceeding in two steps. The first step involves a threshold inquiry into the nature of the speech at issue. If a public employee speaks “pursuant to [his or her] official duties,” this Court has said the Free Speech Clause generally will not shield the individual from an employer’s control and discipline because that kind of speech is—for constitutional purposes at least—the government’s own speech.

At the same time and at the other end of the spectrum, when an employee “speaks as a citizen addressing a matter of public concern,” our cases indicate that the First Amendment may be implicated and courts should proceed to a second step. At this second step, our cases suggest that courts should attempt to engage in “a delicate balancing of the competing interests surrounding the speech and its consequences.” …

… [I]t seems clear to us that Mr. Kennedy has demonstrated that his speech was private speech, not government speech. When Mr. Kennedy uttered the three prayers that resulted in his suspension, he was not engaged in speech “ordinarily within the scope” of his duties as a coach. He did not speak pursuant to government policy. He was not seeking to convey a government-created message. He was not instructing players, discussing strategy, encouraging better on-field performance, or engaged in any other speech the District paid him to produce as a coach. See Part I–B, supra. Simply put: Mr. Kennedy’s prayers did not “ow[e their] existence” to Mr. Kennedy’s responsibilities as a public employee. Garcetti …

Of course, acknowledging that Mr. Kennedy’s prayers represented his own private speech does not end the matter. So far, we have recognized only that Mr. Kennedy has carried his threshold burden. Under the Pickering–Garcetti framework, a second step remains where the government may seek to prove that its interests as employer outweigh even an employee’s private speech on a matter of public concern.

Whether one views the case through the lens of the Free Exercise or Free Speech Clause, at this point the burden shifts to the District … Under the Free Exercise Clause, a government entity normally must satisfy at least “strict scrutiny,” showing that its restrictions on the plaintiff ’s protected rights serve a compelling interest and are narrowly tailored to that end. See Lukumi … A similar standard generally obtains under the Free Speech Clause …

As we have seen, the District argues that its suspension of Mr. Kennedy was essential to avoid a violation of the Establishment Clause. Id., at 35–42. On its account, Mr. Kennedy’s prayers might have been protected by the Free Exercise and Free Speech Clauses. But his rights were in “direct tension” with the competing demands of the Establishment Clause. App. 43. To resolve that clash, the District reasoned, Mr. Kennedy’s rights had to “yield.” Ibid. The Ninth Circuit pursued this same line of thinking …

What the District and the Ninth Circuit overlooked, however, is that the “shortcomings” associated with this “ambitiou[s],” abstract, and ahistorical approach to the Establishment Clause became so “apparent” that this Court long ago abandoned Lemon and its endorsement test offshoot … The Court has explained that these tests “invited chaos” in lower courts, led to “differing results” in materially identical cases, and created a “minefield” for legislators … This Court has since made plain, too, that the Establishment Clause does not include anything like a “modified heckler’s veto, in which … religious activity can be proscribed” based on “‘perceptions’” or “‘discomfort.’” Good News Club v. Milford Central School, (2001) … Nor does the Clause “compel the government to purge from the public sphere” anything an objective observer could reasonably infer endorses or “partakes of the religious.” Van Orden v. Perry, (2005) …

In place of Lemon and the endorsement test, this Court has instructed that the Establishment Clause must be interpreted by “‘reference to historical practices and understandings.’” Town of Greece (2013) … An analysis focused on original meaning and history, this Court has stressed, has long represented the rule rather than some “‘exception’” within the “Court’s Establishment Clause jurisprudence.” Town of Greece (2013) …

[Gorsuch then covers the Districts other reasons and concerns about the Coach’s religious prayers and dismisses each argument.]

In the end, the District’s case hinges on the need to generate conflict between an individual’s rights under the Free Exercise and Free Speech Clauses and its own Establishment Clause duties—and then develop some explanation why one of these Clauses in the First Amendment should “‘trum[p]’” the other two. But the project falters badly. Not only does the District fail to offer a sound reason to prefer one constitutional guarantee over another. It cannot even show that they are at odds. In truth, there is no conflict between the constitutional commands before us. There is only the “mere shadow” of a conflict, a false choice premised on a misconstruction of the Establishment Clause … And in no world may a government entity’s concerns about phantom constitutional violations justify actual violations of an individual’s First Amendment rights …

Respect for religious expressions is indispensable to life in a free and diverse Republic—whether those expressions take place in a sanctuary or on a field, and whether they manifest through the spoken word or a bowed head. Here, a government entity sought to punish an individual for engaging in a brief, quiet, personal religious observance doubly protected by the Free Exercise and Free Speech Clauses of the First Amendment. And the only meaningful justification the government offered for its reprisal rested on a mistaken view that it had a duty to ferret out and suppress religious observances even as it allows comparable secular speech. The Constitution neither mandates nor tolerates that kind of discrimination. Mr. Kennedy is entitled to summary judgment on his First Amendment claims. The judgment of the Court of Appeals is

Reversed.

Justice Sotomayor, with whom Justice Breyer and Kagan join dissenting.

This case is about whether a public school must permit a school official to kneel, bow his head, and say a prayer at the center of a school event. The Constitution does not authorize, let alone require, public schools to embrace this conduct. Since Engel v. Vitale (1962), this Court consistently has recognized that school officials leading prayer is constitutionally impermissible. Official-led prayer strikes at the core of our constitutional protections for the religious liberty of students and their parents, as embodied in both the Establishment Clause and the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment. The Court now charts a different path, yet again paying almost exclusive attention to the Free Exercise Clause’s protection for individual religious exercise while giving short shrift to the Establishment Clause’s prohibition on state establishment of religion. See Carson v. Makin, (2022) (BREYER, J., dissenting). To the degree the Court portrays petitioner Joseph Kennedy’s prayers as private and quiet, it misconstrues the facts. The record reveals that Kennedy had a longstanding practice of conducting demonstrative prayers on the 50- yard line of the football field. Kennedy consistently invited others to join his prayers and for years led student athletes in prayer at the same time and location. The Court ignores this history. The Court also ignores the severe disruption to school events caused by Kennedy’s conduct, viewing it as irrelevant because the Bremerton School District (District) stated that it was suspending Kennedy to avoid it being viewed as endorsing religion. Under the Court’s analysis, presumably this would be a different case if the District had cited Kennedy’s repeated disruptions of school programming and violations of school policy regarding public access to the field as grounds for suspending him. As the District did not articulate those grounds, the Court assesses only the District’s Establishment Clause concerns. It errs by assessing them divorced from the context and history of Kennedy’s prayer practice. Today’s decision goes beyond merely misreading the record. The Court overrules Lemon v. Kurtzman, (1971), and calls into question decades of subsequent precedents that it deems “offshoot[s]” of that decision. Ante, at 22. In the process, the Court rejects longstanding concerns surrounding government endorsement of religion and replaces the standard for reviewing such questions with a new “history and tradition” test. In addition, while the Court reaffirms that the Establishment Clause prohibits the government from coercing participation in religious exercise, it applies a nearly toothless version of the coercion analysis, failing to acknowledge the unique pressures faced by students when participating in school-sponsored activities. This decision does a disservice to schools and the young citizens they serve, as well as to our Nation’s longstanding commitment to the separation of church and state. I respectfully dissent.

As the majority tells it, Kennedy, a coach for the District’s football program, “lost his job” for “pray[ing] quietly while his students were otherwise occupied.” Ante, at 1. The record before us, however, tells a different story.

The District serves approximately 5,057 students and employs 332 teachers and 400 nonteaching personnel in Kitsap County, Washington. The county is home to Bahá’ís, Buddhists, Hindus, Jews, Muslims, Sikhs, Zoroastrians, and many denominations of Christians, as well as numerous residents who are religiously unaffiliated. See Brief for Religious and Denominational Organizations et al. as Amici Curiae.

… The District also set requirements for Kennedy’s interactions with players, obliging him, like all coaches, to “exhibit sportsmanlike conduct at all times,” “utilize positive motivational strategies to encourage athletic performance,” and serve as a “mentor and role model for the student athletes.” App., at 56. In addition, Kennedy’s position made him responsible for interacting with members of the community. In this capacity, the District required Kennedy and other coaches to “maintain positive media relations,” “always approach officials with composure” with the expectation that they were “constantly being observed by others,” and “communicate effectively” with parents. Ibid.

Finally, District coaches had to “[a]dhere to [District] policies and administrative regulations” more generally. Id., at 30–31.

In September 2015, a coach from another school’s football team informed BHS’ principal that Kennedy had asked him and his team to join Kennedy in prayer … The District initiated an inquiry into whether its policy on Religious-Related Activities and Practices had been violated. It learned that, since his hiring in 2008, Kennedy had been kneeling on the 50-yard line to pray immediately after shaking hands with the opposing team. Kennedy recounted that he initially prayed alone and that he never asked any student to join him. Over time, however, a majority of the team came to join him, with the numbers varying from game to game. Kennedy’s practice evolved into postgame talks in which Kennedy would hold aloft student helmets and deliver speeches with “overtly religious references,” which Kennedy described as prayers, while the players kneeled around him. Id., at 40 …

While the District’s inquiry was pending, its athletic director attended BHS’ September 11, 2015, football game and told Kennedy that he should not be conducting prayers with players. After the game, while the athletic director watched, Kennedy led a prayer out loud, holding up a player’s helmet as the players kneeled around him. While riding the bus home with the team, Kennedy posted on Facebook that he thought he might have just been fired for praying.

On September 17, the District’s superintendent sent Kennedy a letter informing him that leading prayers with students on the field and in the locker room would likely be found to violate the Establishment Clause, exposing the District to legal liability. The District acknowledged that Kennedy had “not actively encouraged, or required, participation” but emphasized that “school staff may not indirectly encourage students to engage in religious activity” or “endors[e]” religious activity; rather, the District explained, staff “must remain neutral” “while performing their job duties.” Id., at 41–43. The District instructed Kennedy that any motivational talks to students must remain secular, “so as to avoid alienation of any team member.” Id., at 44.

The District reiterated that “all District staff are free to engage in religious activity, including prayer, so long as it does not interfere with job responsibilities.” Id., at 45. To avoid endorsing student religious exercise, the District instructed that such activity must be nondemonstrative or conducted separately from students, away from student activities. Ibid …

Kennedy stopped participating in locker room prayers and, after a game the following day, gave a secular speech. He returned to pray in the stadium alone after his duties were over and everyone had left the stadium, to which the District had no objection. Kennedy then hired an attorney, who, on October 14, sent a letter explaining that Kennedy was “motivated by his sincerely-held religious beliefs to pray following each football game.” Id., at 63 … The letter further announced that Kennedy would resume his 50-yard-line prayer practice the next day after the October 16 homecoming game.1 Before the homecoming game, Kennedy made multiple media appearances to publicize his plans to pray at the 50- yard line, leading to an article in the Seattle News and a local television broadcast about the upcoming homecoming game. In the wake of this media coverage, the District began receiving a large number of emails, letters, and calls, many of them threatening.

… While Kennedy’s letter asserted that his prayers “occurr[ed] ‘on his own time,’ after his duties as a District employee had ceased,” the District pointed out that Kennedy “remain[ed] on duty” when his prayers occurred “immediately following completion of the football game, when students are still on the football field, in uniform, under the stadium lights, with the audience still in attendance, and while Mr. Kennedy is still in his District-issued and District-logoed attire.” Id., at 78 (emphasis deleted).

… The District stated that it had no objection to Kennedy returning to the stadium when he was off duty to pray at the 50-yard line, nor with Kennedy praying while on duty if it did not interfere with his job duties or suggest the District’s endorsement of religion …

On October 16, after playing of the game had concluded, Kennedy shook hands with the opposing team, and as advertised, knelt to pray while most BHS players were singing the school’s fight song. He quickly was joined by coaches and players from the opposing team. Television news cameras surrounded the group. Members of the public rushed the field to join Kennedy, jumping fences to access the field and knocking over student band members. After the game, the District received calls from Satanists who “‘intended to conduct ceremonies on the field after football games if others were allowed to.’” Id., at 181. To secure the field and enable subsequent games to continue safely, the District was forced to make security arrangements with the local police and to post signs near the field and place robocalls to parents reiterating that the field was not open to the public.

10/16/2015

The District sent Kennedy another letter on October 23, explaining that his conduct at the October 16 game was inconsistent with the District’s requirements … Again, the District emphasized that it was happy to accommodate Kennedy’s desire to pray on the job in a way that did not interfere with his duties or risk perceptions of endorsement …

Kennedy did not directly respond or suggest a satisfactory accommodation. Instead, his attorneys told the media that he would accept only demonstrative prayer on the 50- yard line immediately after games. During the October 23 and October 26 games, Kennedy again prayed at the 50- yard line immediately following the game, while postgame activities were still ongoing …

… After the issues with Kennedy arose, several parents reached out to the District saying that their children had participated in Kennedy’s prayers solely to avoid separating themselves from the rest of the team. No BHS students appeared to pray on the field after Kennedy’s suspension …

Kennedy then filed suit. He contended, as relevant, that the District violated his rights under the Free Speech and Free Exercise Clauses of the First Amendment … Properly understood, this case is not about the limits on an individual’s ability to engage in private prayer at work. This case is about whether a school district is required to allow one of its employees to incorporate a public, communicative display of the employee’s personal religious beliefs into a school event, where that display is recognizable as part of a longstanding practice of the employee ministering religion to students as the public watched. A school district is not required to permit such conduct; in fact, the Establishment Clause prohibits it from doing so …

The Establishment Clause protects this freedom by “command[ing] a separation of church and state.” Cutter v. Wilkinson, (2005) …

Indeed, “[t]he Court has been particularly vigilant in monitoring compliance with the Establishment Clause in elementary and secondary schools.” Edwards v. Aguillard, (1987). The reasons motivating this vigilance inhere in the nature of schools themselves and the young people they serve. Two are relevant here. First, government neutrality toward religion is particularly important in the public school context given the role public schools play in our society … Accordingly, the Establishment Clause “proscribes public schools from ‘conveying or attempting to convey a message that religion or a particular religious belief is favored or preferred’” or otherwise endorsing religious beliefs. Lee, (Blackmun, J., concurring).

Second, schools face a higher risk of unconstitutionally “coerc[ing] … support or participat[ion] in religion or its exercise” than other government entities. Id., at 587 (opinion of the Court) … Moreover, the State exercises that great authority over children, who are uniquely susceptible to “subtle coercive pressure.” Lee … Accordingly, this Court has emphasized that “the State may not, consistent with the Establishment Clause, place primary and secondary school children” in the dilemma of choosing between “participating, with all that implies, or protesting” a religious exercise in a public school. Lee.

Given the twin Establishment Clause concerns of endorsement and coercion, it is unsurprising that the Court has consistently held integrating prayer into public school activities to be unconstitutional, including when student participation is not a formal requirement or prayer is silent …

Under these precedents, the Establishment Clause violation at hand is clear … Kennedy’s tradition of a 50-yard line prayer thus strikes at the heart of the Establishment Clause’s concerns about endorsement. For students and community members at the game, Coach Kennedy was the face and the voice of the District during football games … Although the football game itself had ended, the football game events had not; Kennedy himself acknowledged that his responsibilities continued until the players went home. Kennedy’s postgame responsibilities were what placed Kennedy on the 50-yard line in the first place; that was, after all, where he met the opposing team to shake hands after the game. Permitting a school coach to lead students and others he invited onto the field in prayer at a predictable time after each game could only be viewed as a postgame tradition occurring “with the approval of the school administration.” Santa Fe.

Kennedy’s prayer practice also implicated the coercion concerns at the center of this Court’s Establishment Clause jurisprudence … The record before the Court bears this out …

Kennedy does not defend his longstanding practice of leading the team in prayer out loud on the field as they kneeled around him. Instead, he responds, and the Court accepts, that his highly visible and demonstrative prayer at the last three games before his suspension did not violate the Establishment Clause because these prayers were quiet and thus private. This Court’s precedents, however, do not permit isolating government actions from their context in determining whether they violate the Establishment Clause. To the contrary, this Court has repeatedly stated that Establishment Clause inquiries are fact specific and require careful consideration of the origins and practical reality of the specific practice at issue … This Court’s precedent thus does not permit treating Kennedy’s “new” prayer practice as occurring on a blank slate, any more than those in the District’s school community would have experienced Kennedy’s changed practice (to the degree there was one) as erasing years of prior actions by Kennedy. …

Finally, Kennedy stresses that he never formally required students to join him in his prayers. But existing precedents do not require coercion to be explicit, particularly when children are involved …

Despite the overwhelming precedents establishing that school officials leading prayer violates the Establishment Clause, the Court today holds that Kennedy’s midfield prayer practice did not violate the Establishment Clause. This decision rests on an erroneous understanding of the Religion Clauses. It also disregards the balance this Court’s cases strike among the rights conferred by the Clauses. The Court relies on an assortment of pluralities, concurrences, and dissents by Members of the current majority to effect fundamental changes in this Court’s Religion Clauses jurisprudence, all the while proclaiming that nothing has changed at all …

The Free Exercise Clause and Establishment Clause are equally integral in protecting religious freedom in our society. The first serves as “a promise from our government,” while the second erects a “backstop that disables our government from breaking it” and “start[ing] us down the path to the past, when [the right to free exercise] was routinely abridged.” Trinity Lutheran Church of Columbia, Inc. v. Comer, (2017) (Sotomayor, J., dissenting). Today, the Court once again weakens the backstop. It elevates one individual’s interest in personal religious exercise, in the exact time and place of that individual’s choosing, over society’s interest in protecting the separation between church and state, eroding the protections for religious liberty for all. Today’s decision is particularly misguided because it elevates the religious rights of a school official, who voluntarily accepted public employment and the limits that public employment entails, over those of his students, who are required to attend school and who this Court has long recognized are particularly vulnerable and deserving of protection. In doing so, the Court sets us further down a perilous path in forcing States to entangle themselves with religion, with all of our rights hanging in the balance. As much as the Court protests otherwise, today’s decision is no victory for religious liberty. I respectfully dissent.

10/26/2015