Speech and Expression

Defining Danger and Speech

Schenck v. U.S. (1919)

249 U.S. 47 (1919)

Vote: 9-0

Majority: Holmes, joined by White, McKenna, Day, Van Devanter, Pitney, McReynolds, Brandeis and Clarke

Mr. Justice HOLMES delivered the opinion of the Court.

This is an indictment in three counts. The first charges a conspiracy to violate the Espionage Act … by causing and attempting to cause insubordination, &c., in the military and naval forces of the United States, and to obstruct the recruiting and enlistment service of the United States, when the United States was at war with the German Empire, to-wit, that the defendant willfully conspired to have printed and circulated to men who had been called and accepted for military service under the Act of May 18, 1917 … a document set forth and alleged to be calculated to cause such insubordination and obstruction. The second count alleges a conspiracy to commit an offense against the United States, to-wit, to use the mails for the transmission of matter declared to be non-mailable by … the Act of June 15, 1917 … The third count charges an unlawful use of the mails for the transmission of the same matter and otherwise as above. The defendants were found guilty on all the counts. They set up the First Amendment to the Constitution forbidding Congress to make any law abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press, and bringing the case here on that ground have argued some other points also of which we must dispose.

…

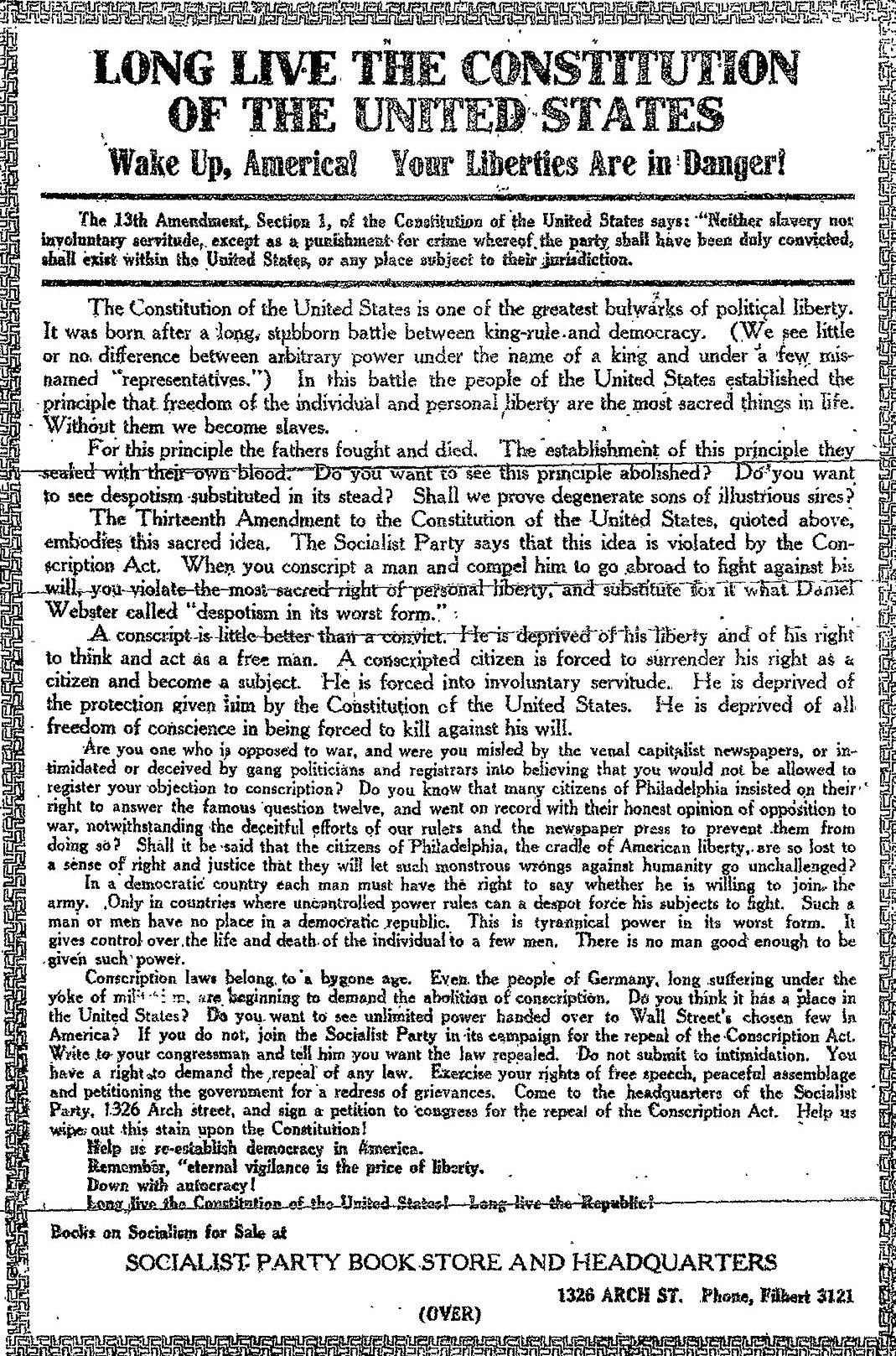

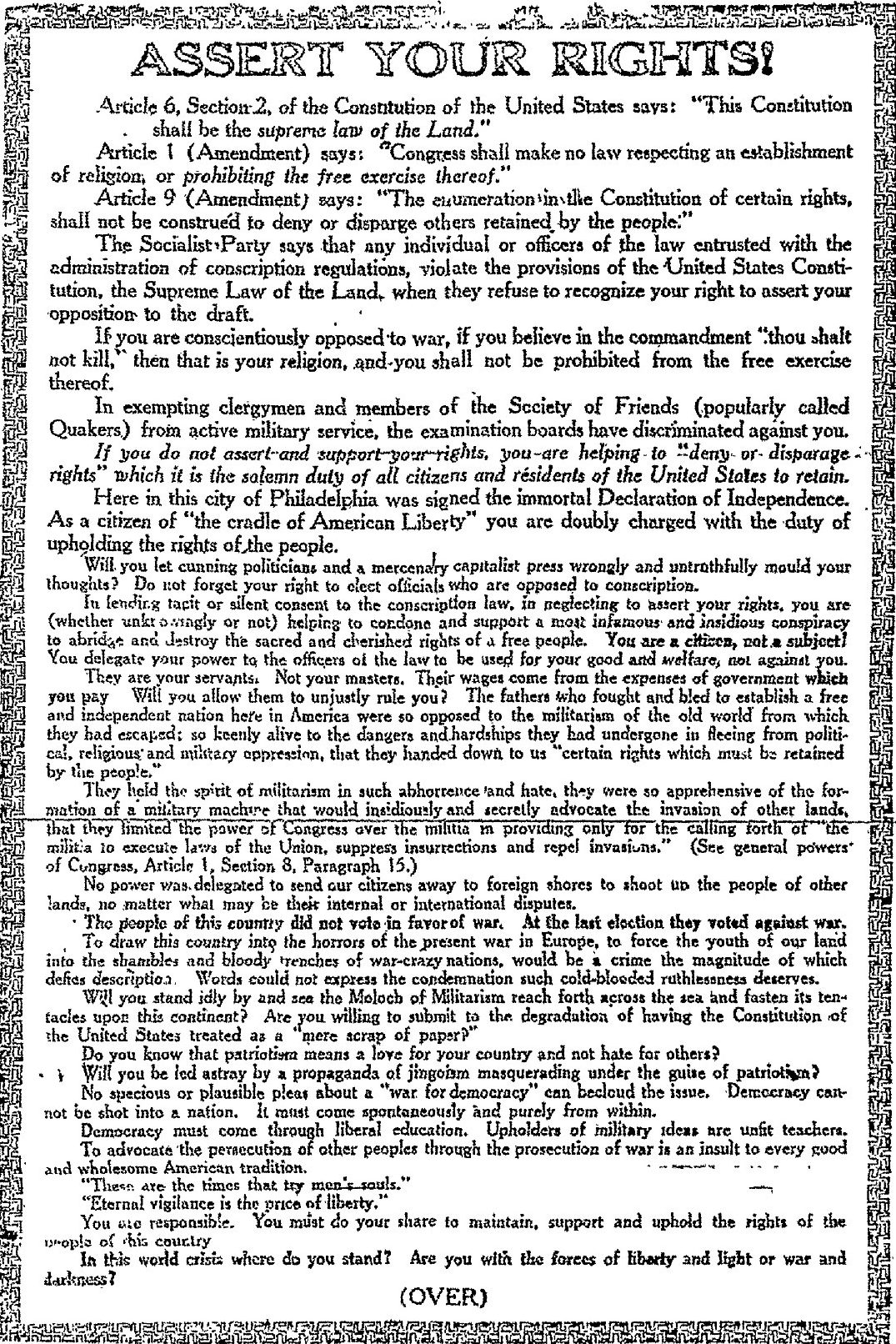

The document in question, upon its first printed side, recited the first section of the Thirteenth Amendment, said that the idea embodied in it was violated by the Conscription Act, and that a conscript is little better than a convict. In impassioned language, it intimated that conscription was despotism in its worst form, and a monstrous wrong against humanity in the interest of Wall Street’s chosen few. It said “Do not submit to intimidation,” but in form, at least, confined itself to peaceful measures such as a petition for the repeal of the act. The other and later printed side of the sheet was headed “Assert Your Rights.” It stated reasons for alleging that anyone violated the Constitution when he refused to recognize “your right to assert your opposition to the draft,” and went on

“If you do not assert and support your rights, you are helping to deny or disparage rights which it is the solemn duty of all citizens and residents of the United States to retain.”

It described the arguments on the other side as coming from cunning politicians and a mercenary capitalist press, and even silent consent to the conscription law as helping to support an infamous conspiracy. It denied the power to send our citizens away to foreign shores to shoot up the people of other lands, and added that words could not express the condemnation such cold-blooded ruthlessness deserves, &c., &c., winding up, “You must do your share to maintain, support and uphold the rights of the people of this country.” Of course, the document would not have been sent unless it had been intended to have some effect, and we do not see what effect it could be expected to have upon persons subject to the draft except to influence them to obstruct the carrying of it out. The defendants do not deny that the jury might find against them on this point.

But it is said, suppose that that was the tendency of this circular, it is protected by the First Amendment to the Constitution. Two of the strongest expressions are said to be quoted respectively from well-known public men. It well may be that the prohibition of laws abridging the freedom of speech is not confined to previous restraints, although to prevent them may have been the main purpose. Patterson v Colorado, (1907). We admit that in many places and in ordinary times the defendants in saying all that was said in the circular would have been within their constitutional rights. But the character of every act depends upon the circumstances in which it is done. The most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing a panic. It does not even protect a man from an injunction against uttering words that may have all the effect of force. The question in every case is whether the words used are used in such circumstances and are of such a nature as to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive evils that Congress has a right to prevent. It is a question of proximity and degree. When a nation is at war many things that might be said in time of peace are such a hindrance to its effort that their utterance will not be endured so long as men fight and that no Court could regard them as protected by any constitutional right. It seems to be admitted that if an actual obstruction of the recruiting service were proved, liability for words that produced that effect might be enforced. The statute of 1917 in section 4 (Comp. St. 1918, § 10212d) punishes conspiracies to obstruct as well as actual obstruction. If the act, (speaking, or circulating a paper,) its tendency and the intent with which it is done are the same, we perceive no ground for saying that success alone warrants making the act a crime …

Judgments affirmed.

Podcast Link (Spotify): https://open.spotify.com/episode/34OotU0AbneH0Devk9aUmt?si=hrMRwrw1Qhm2JJUhAu9iNg&dl_branch=1

Abrams v. United States (1919)

250 U.S. 216 (1919)

Vote: 7-2

Decision: for the United States

Majority: Clarke, joined by White, McKenna, Day, Van Devanter, Pitney, and McReynolds

Dissent: Holmes, joined by Brandeis

Mr. Justice Clarke delivered the opinion of the Court.

On a single indictment, containing four counts, the five plaintiffs in error, hereinafter designated the defendants, were convicted of conspiring to violate provisions of the Espionage Act of Congress.

Each of the first three counts charged the defendants with conspiring, when the United States was at war with the Imperial Government of Germany, to unlawfully utter, print, write and publish: in the first count, “disloyal, scurrilous and abusive language about the form of Government of the United States;” in the second count, language “intended to bring the form of Government of the United States into contempt, scorn, contumely and disrepute;” and in the third count, language “intended to incite, provoke and encourage resistance to the United States in said war.” The charge in the fourth count was that the defendants conspired,

“when the United States was at war with the Imperial German Government, unlawfully and willfully, by utterance, writing, printing and publication, to urge, incite and advocate curtailment of production of things and products, to-wit, ordnance and ammunition, necessary and essential to the prosecution of the war.”

The offenses were charged in the language of the act of Congress.

It was charged in each count of the indictment that it was a part of the conspiracy that the defendants would attempt to accomplish their unlawful purpose by printing, writing and distributing in the City of New York many copies of a leaflet or circular, printed in the English language, and of another printed in the Yiddish language, copies of which, properly identified, were attached to the indictment.

All of the five defendants were born in Russia. They were intelligent, had considerable schooling, and, at the time they were arrested, they had lived in the United States terms varying from five to ten years, but none of them had applied for naturalization. Four of them testified as witnesses in their own behalf, and, of these, three frankly avowed that they were “rebels,” “revolutionists,” “anarchists,” that they did not believe in government in any form, and they declared that they had no interest whatever in the Government of the United States. The fourth defendant testified that he was a “socialist,” and believed in “a proper kind of government, not capitalistic,” but, in his classification, the Government of the United States was “capitalistic.”

It was admitted on the trial that the defendants had united to print and distribute the described circulars, and that five thousand of them had been printed and distributed about the 22nd day of August, 1918.

The defendants pleaded “not guilty,” and the case of the Government consisted in showing the facts we have stated, and in introducing in evidence copies of the two printed circulars attached to the indictment …

* * * [The Court excerpted the leaflets].

These excerpts sufficiently show that, while the immediate occasion for this particular outbreak of lawlessness on the part of the defendant alien anarchists may have been resentment caused by our Government’s sending troops into Russia as a strategic operation against the Germans on the eastern battlefront, yet the plain purpose of their propaganda was to excite, at the supreme crisis of the war, disaffection, sedition, riots, and, as they hoped, revolution, in this country for the purpose of embarrassing, and, if possible, defeating the military plans of the Government in Europe. A technical distinction may perhaps be taken between disloyal and abusive language applied to the form of our government or language intended to bring the form of our government into contempt and disrepute, and language of like character and intended to produce like results directed against the President and Congress, the agencies through which that form of government must function in time of war. But it is not necessary to a decision of this case to consider whether such distinction is vital or merely formal, for the language of these circulars was obviously intended to provoke and to encourage resistance to the United States in the war, as the third count runs, and the defendants, in terms, plainly urged and advocated a resort to a general strike of workers in ammunition factories for the purpose of curtailing the production of ordnance and munitions necessary and essential to the prosecution of the war as is charged in the fourth count. Thus, it is clear not only that some evidence, but that much persuasive evidence, was before the jury tending to prove that the defendants were guilty as charged in both the third and fourth counts of the indictment, and, under the long established rule of law hereinbefore stated, the judgment of the District Court must be

Affirmed.

Mr. Justice Holmes Dissenting [Mr. Justice Brandeis Joins].

…

The first of these leaflets says that the President’s cowardly silence about the intervention in Russia reveals the hypocrisy of the plutocratic gang in Washington. It intimates that “German militarism combined with allied capitalism to crush the Russian evolution ” — goes on that the tyrants of the world fight each other until they see a common enemy — working class enlightenment, when they combine to crush it, and that now militarism and capitalism combined, though not openly, to crush the Russian revolution. It says that there is only one enemy of the workers of the world, and that is capitalism; that it is a crime for workers of America, &c., to fight the workers’ republic of Russia, and ends “Awake! Awake, you Workers of the World, Revolutionists!” A note adds

“It is absurd to call us pro-German. We hate and despise German militarism more than do you hypocritical tyrants. We have more reasons for denouncing German militarism than has the coward of the White House.”

The other leaflet, headed “Workers — Wake Up,” with abusive language says that America together with the Allies will march for Russia to help the Czecko-Slovaks in their struggle against the Bolsheviki, and that this time the hypocrites shall not fool the Russian emigrants and friends of Russia in America … The leaflet winds up by saying “Workers, our reply to this barbaric intervention has to be a general strike!” and, after a few words on the spirit of revolution, exhortations not to be afraid, and some usual tall talk ends, “Woe unto those who will be in the way of progress. Let solidarity live! The Rebels.”

No argument seems to me necessary to show that these pronunciamentos in no way attack the form of government of the United States … With regard to that, it seems too plain to be denied that the suggestion to workers in the ammunition factories that they are producing bullets to murder their dearest, and the further advocacy of a general strike, both in the second leaflet, do urge curtailment of production of things necessary to the prosecution of the war … But to make the conduct criminal, that statute requires that it should be “with intent by such curtailment to cripple or hinder the United States in the prosecution of the war.” It seems to me that no such intent is proved.

I am aware, of course, that the word intent as vaguely used in ordinary legal discussion means no more than knowledge at the time of the act that the consequences said to be intended will ensue. Even less than that will satisfy the general principle of civil and criminal liability. A man may have to pay damages, may be sent to prison, at common law might be hanged, if, at the time of his act, he knew facts from which common experience showed that the consequences would follow, whether he individually could foresee them or not. But, when words are used exactly, a deed is not done with intent to produce a consequence unless that consequence is the aim of the deed. It may be obvious, and obvious to the actor, that the consequence will follow, and he may be liable for it even if he regrets it, but he does not do the act with intent to produce it unless the aim to produce it is the proximate motive of the specific act, although there may be some deeper motive behind.

It seems to me that this statute must be taken to use its words in a strict and accurate sense. They would be absurd in any other. A patriot might think that we were wasting money on aeroplanes, or making more cannon of a certain kind than we needed, and might advocate curtailment with success, yet, even if it turned out that the curtailment hindered and was thought by other minds to have been obviously likely to hinder the United States in the prosecution of the war, no one would hold such conduct a crime …

But, as against dangers peculiar to war, as against others, the principle of the right to free speech is always the same. It is only the present danger of immediate evil or an intent to bring it about that warrants Congress in setting a limit to the expression of opinion where private rights are not concerned. Congress certainly cannot forbid all effort to change the mind of the country. Now nobody can suppose that the surreptitious publishing of a silly leaflet by an unknown man, without more, would present any immediate danger that its opinions would hinder the success of the government arms or have any appreciable tendency to do so. Publishing those opinions for the very purpose of obstructing, however, might indicate a greater danger, and, at any rate, would have the quality of an attempt … It is necessary where the success of the attempt depends upon others because, if that intent is not present, the actor’s aim may be accomplished without bringing about the evils sought to be checked. An intent to prevent interference with the revolution in Russia might have been satisfied without any hindrance to carrying on the war in which we were engaged.

… Persecution for the expression of opinions seems to me perfectly logical. If you have no doubt of your premises or your power, and want a certain result with all your heart, you naturally express your wishes in law, and sweep away all opposition. To allow opposition by speech seems to indicate that you think the speech impotent, as when a man says that he has squared the circle, or that you do not care wholeheartedly for the result, or that you doubt either your power or your premises. But when men have realized that time has upset many fighting faiths, they may come to believe even more than they believe the very foundations of their own conduct that the ultimate good desired is better reached by free trade in ideas — that the best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market, and that truth is the only ground upon which their wishes safely can be carried out. That, at any rate, is the theory of our Constitution. It is an experiment, as all life is an experiment. Every year, if not every day, we have to wager our salvation upon some prophecy based upon imperfect knowledge. While that experiment is part of our system, I think that we should be eternally vigilant against attempts to check the expression of opinions that we loathe and believe to be fraught with death, unless they so imminently threaten immediate interference with the lawful and pressing purposes of the law that an immediate check is required to save the country. I wholly disagree with the argument of the Government that the First Amendment left the common law as to seditious libel in force. History seems to me against the notion. I had conceived that the United States, through many years, had shown its repentance for the Sedition Act of 1798, by repaying fines that it imposed. Only the emergency that makes it immediately dangerous to leave the correction of evil counsels to time warrants making any exception to the sweeping command, “Congress shall make no law … abridging the freedom of speech.” Of course, I am speaking only of expressions of opinion and exhortations, which were all that were uttered here, but I regret that I cannot put into more impressive words my belief that, in their conviction upon this indictment, the defendants were deprived of their rights under the Constitution of the United States.

Gitlow v. New York (1925)

268 U.S. 652 (1925)

Vote: 7-2

Majority: Sanford, joined by Taft, Van Devanter, McReynolds, Sutherland, Butler, Sanford and Stone

Dissent: Homes, joined by Brandeis

Mr. Justice Sanford delivered the opinion of the Court.

Benjamin Gitlow was indicted in the Supreme Court of New York, with three others, for the statutory crime of criminal anarchy. New York Penal Laws, §§ 160, 161. * * * The contention here is that the statute, by its terms and as applied in this case, is repugnant to the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Its material provisions are:

“§ 160. Criminal anarchy defined. Criminal anarchy is the doctrine that organized government should be overthrown by force or violence, or by assassination of the executive head or of any of the executive officials of government, or by any unlawful means. The advocacy of such doctrine either by word of mouth or writing is a felony.”

“§ 161. Advocacy of criminal anarchy. Any person who:”

“1. By word of mouth or writing advocates, advises or teaches the duty, necessity or propriety of overthrowing or overturning organized government by force or violence, or by assassination of the executive head or of any of the executive officials of government, or by any unlawful means; or,”

“2. Prints, publishes, edits, issues or knowingly circulates, sells, distributes or publicly displays any book, paper, document, or written or printed matter in any form, containing or advocating, advising or teaching the doctrine that organized government should be overthrown by force, violence or any unlawful means”

“Is guilty of a felony and punishable by imprisonment or fine, or both.”

The indictment was in two counts. The first charged that the defendant had advocated, advised and taught the duty, necessity and propriety of overthrowing and overturning organized government by force, violence and unlawful means, by certain writings therein set forth entitled “The Left Wing Manifesto”; the second, that he had printed, published and knowingly circulated and distributed a certain paper called “The Revolutionary Age,” containing the writings set forth in the first count advocating, advising and teaching the doctrine that organized government should be overthrown by force, violence and unlawful means. * * *

… The Left Wing Section was organized nationally at a conference in New York City in June, 1919, attended by ninety delegates from twenty different States. The conference elected a National Council, of which the defendant was a member, and left to it the adoption of a “Manifesto.” This was published in The Revolutionary Age, the official organ of the Left Wing. * * * Sixteen thousand copies were printed, which were delivered at the premises in New York City used as the office of the Revolutionary Age and the headquarters of the Left Wing, and occupied by the defendant and other officials. These copies were paid for by the defendant, as business manager of the paper. Employees at this office wrapped and mailed out copies of the paper under the defendant’s direction, and copies were sold from this office. It was admitted that the defendant signed a card subscribing to the Manifesto and Program of the Left Wing, which all applicants were required to sign before being admitted to membership; that he went to different parts of the State to speak to branches of the Socialist Party about the principles of the Left Wing and advocated their adoption, and that he was responsible for the Manifesto as it appeared, that “he knew of the publication, in a general way, and he knew of its publication afterwards, and is responsible for its circulation.”

There was no evidence of any effect resulting from the publication and circulation of the Manifesto. * * *

Coupled with a review of the rise of Socialism, [the Manifesto] condemned the dominant “moderate Socialism” for its recognition of the necessity of the democratic parliamentary state; repudiated its policy of introducing Socialism by legislative measures, and advocated, in plain and unequivocal language, the necessity of accomplishing the “Communist Revolution” by a militant and “revolutionary Socialism”, based on “the class struggle” and mobilizing the “power of the proletariat in action,” through mass industrial revolts developing into mass political strikes and “revolutionary mass action”, for the purpose of conquering and destroying the parliamentary state and establishing in its place, through a “revolutionary dictatorship of the proletariat”, the system of Communist Socialism. The then recent strikes … were cited as instances of … revolutionary action … it was urged … to broaden the strike, make it general and militant, and develop it into mass political strikes and revolutionary mass action for the annihilation of the parliamentary state.

* * * [Gitlow was convicted and the convictions upheld by the New York courts.]

The sole contention here is, essentially, that as there was no evidence of any concrete result flowing from the publication of the Manifesto or of circumstances showing the likelihood of such result, the statute as construed and applied by the trial court penalizes the mere utterance, as such, of “doctrine” having no quality of incitement, without regard either to the circumstances of its utterance or to the likelihood of unlawful sequences, and that, as the exercise of the right of free expression with relation to government is only punishable “in circumstances involving likelihood of substantive evil,” the statute contravenes the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The argument in support of this contention rests primarily upon the following propositions: 1st, that the “liberty” protected by the Fourteenth Amendment includes the liberty of speech and of the press, and 2nd, that while liberty of expression “is not absolute,” it may be restrained “only in circumstances where its exercise bears a causal relation with some substantive evil, consummated, attempted or likely,” and as the statute “takes no account of circumstances,” it unduly restrains this liberty and is therefore unconstitutional.

The precise question presented, and the only question which we can consider under this writ of error, then is whether the statute, as construed and applied in this case by the state courts, deprived the defendant of his liberty of expression in violation of the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

The statute does not penalize the utterance or publication of abstract “doctrine” or academic discussion having no quality of incitement to any concrete action. It is not aimed against mere historical or philosophical essays. It does not restrain the advocacy of changes in the form of government by constitutional and lawful means. What it prohibits is language advocating, advising or teaching the overthrow of organized government by unlawful means. These words imply urging to action. Advocacy is defined in the Century Dictionary as: “1. The act of pleading for, supporting, or recommending; active espousal.” It is not the abstract “doctrine” of overthrowing organized government by unlawful means which is denounced by the statute, but the advocacy of action for the accomplishment of that purpose …

The Manifesto, plainly, is neither the statement of abstract doctrine nor, as suggested by counsel, mere prediction that industrial disturbances and revolutionary mass strikes will result spontaneously in an inevitable process of evolution in the economic system. It advocates and urges in fervent language mass action which shall progressively foment industrial disturbances and, through political mass strikes and revolutionary mass action, overthrow and destroy organized parliamentary government. It concludes with a call to action in these words:

“The proletariat revolution and the Communist reconstruction of society — the struggle for these — is now indispensable. … The Communist International calls the proletariat of the world to the final struggle!”

This is not the expression of philosophical abstraction, the mere prediction of future events; it is the language of direct incitement.

… That the jury were warranted in finding that the Manifesto advocated not merely the abstract doctrine of overthrowing organized government by force, violence and unlawful means, but action to that end, is clear …

It is a fundamental principle, long established, that the freedom of speech and of the press which is secured by the Constitution does not confer an absolute right to speak or publish, without responsibility, whatever one may choose, or an unrestricted and unbridled license that gives immunity for every possible use of language and prevents the punishment of those who abuse this freedom. * * * Reasonably limited … this freedom is an inestimable privilege in a free government; without such limitation, it might become the scourge of the republic.

That a State in the exercise of its police power may punish those who abuse this freedom by utterances inimical to the public welfare, tending to corrupt public morals, incite to crime, or disturb the public peace, is not open to question. * * *

And, for yet more imperative reasons, a State may punish utterances endangering the foundations of organized government and threatening its overthrow by unlawful means … And a State may penalize utterances which openly advocate the overthrow of the representative and constitutional form of government of the United States and the several States, by violence or other unlawful means. In short, this freedom does not deprive a State of the primary and essential right of self-preservation, which, so long as human governments endure, they cannot be denied. * * *

That utterances inciting to the overthrow of organized government by unlawful means present a sufficient danger of substantive evil to bring their punishment within the range of legislative discretion is clear. Such utterances, by their very nature, involve danger to the public peace and to the security of the State. They threaten breaches of the peace, and ultimate revolution. And the immediate danger is none the less real and substantial because the effect of a given utterance cannot be accurately foreseen. The State cannot reasonably be required to measure the danger from every such utterance in the nice balance of a jeweler’s scale. A single revolutionary spark may kindle a fire that, smouldering for a time, may burst into a sweeping and destructive conflagration. It cannot be said that the State is acting arbitrarily or unreasonably when, in the exercise of its judgment as to the measures necessary to protect the public peace and safety, it seeks to extinguish the spark without waiting until it has enkindled the flame or blazed into the conflagration. It cannot reasonably be required to defer the adoption of measures for its own peace and safety until the revolutionary utterances lead to actual disturbances of the public peace or imminent and immediate danger of its own destruction; but it may, in the exercise of its judgment, suppress the threatened danger in its incipiency.

We cannot hold that the present statute is an arbitrary or unreasonable exercise of the police power of the State unwarrantably infringing the freedom of speech or press, and we must and do sustain its constitutionality.

And finding, for the reasons stated, that the statute is not, in itself, unconstitutional, and that it has not been applied in the present case in derogation of any constitutional right, the judgment of the Court of Appeals is

Affirmed.

Terminiello v. Chicago (1949)

337 U.S. 1 (1949)

Vote: 5-4

Majority: Douglas, joined by Black, Reed, Murphy, and Rutledge

Dissent: Vinson

Dissent: Frankfurter, joined by Jackson and Burton

Dissent: Jackson, joined by Burton

Petitioner after jury trial was found guilty of disorderly conduct in violation of a city ordinance of Chicago, and fined. The case grew out of an address he delivered in an auditorium in Chicago under the auspices of the Christian Veterans of America. The meeting commanded considerable public attention. The auditorium was filled to capacity, with over eight hundred persons present. Others were turned away. Outside of the auditorium, a crowd of about one thousand persons gathered to protest against the meeting. A cordon of policemen was assigned to the meeting to maintain order, but they were not able to prevent several disturbances. The crowd outside was angry and turbulent.

Petitioner in his speech condemned the conduct of the crowd outside and vigorously, if not viciously, criticized various political and racial groups whose activities he denounced as inimical to the nation’s welfare.

The trial court charged that ‘breach of the peace’ consists of any ‘misbehavior which violates the public peace and decorum’; and that the ‘misbehavior may constitute a breach of the peace if it stirs the public to anger, invites dispute, brings about a condition of unrest, or creates a disturbance, or if it molests the inhabitants in the enjoyment of peace and quiet by arousing alarm.’

Petitioner did not take exception to that instruction. But he maintained at all times that the ordinance as applied to his conduct violated his right of free speech … The case is here on a petition for certiorari which we granted because of the importance of the question presented.

… As we have noted, the statutory words ‘breach of the peace’ were defined in instructions to the jury to include speech which ‘stirs the public to anger, invites dispute, brings about a condition or unrest, or creates a disturbance …

The vitality of civil and political institutions in our society depends on free discussion … it is only through free debate and free exchange of ideas that government remains responsive to the will of the people and peaceful change is effected. The right to speak freely and to promote diversity of ideas and programs is therefore one of the chief distinctions that sets us apart from totalitarian regimes.

Accordingly a function of free speech under our system of government is to invite dispute. It may indeed best serve its high purpose when it induces a condition of unrest, creates dissatisfaction with conditions as they are, or even stirs people to anger. Speech is often provocative and challenging. It may strike at prejudices and preconceptions and have profound unsettling effects as it presses for acceptance of an idea. That is why freedom of speech, though not absolute, Chaplinsky v NH, (1942), is nevertheless protected against censorship or punishment, unless shown likely to produce a clear and present danger of a serious substantive evil that rises far above public inconvenience, annoyance, or unrest. Bridges v California, (1941). There is no room under our Constitution for a more restrictive view. For the alternative would lead to standardization of ideas either by legislatures, courts, or dominant political or community groups.

The ordinance as construed by the trial court seriously invaded this province. It permitted conviction of petitioner if his speech stirred people to anger, invited public dispute, or brought about a condition of unrest. A conviction resting on any of those grounds may not stand …

… As we have said, the gloss which Illinois placed on the ordinance gives it a meaning and application which are conclusive on us. We need not consider whether as construed it is defective in its entirety. As construed and applied it at least contains parts that are unconstitutional. The verdict was a general one; and we do not know on this record but what it may rest on the invalid clauses.

The statute as construed in the charge to the jury was passed on by the Illinois courts and sustained by them over the objection that as so read it violated the Fourteenth Amendment. The fact that the parties did not dispute its construction makes the adjudication no less ripe for our review … We can only take the statute as the state courts read it … The pinch of the statute is in its application. It is that question which the petitioner has brought here …

But it is said that throughout the appellate proceedings the Illinois courts assumed that the only conduct punishable and punished under the ordinance was conduct constituting ‘fighting words.’ That emphasizes, however, the importance of the rule of the Stromberg case. Petitioner was not convicted under a statute so narrowly construed. For all anyone knows he was convicted under the parts of the ordinance (as construed) which, for example, make it an offense merely to invite dispute or to bring about a condition of unrest. We cannot avoid that issue by saying that all Illinois did was to measure petitioner’s conduct, not the ordinance, against the Constitution. Petitioner raised both points that his speech was protected by the constitution; that the inclusion of his speech within the ordinance was a violation of the Constitution. We would, therefore, strain at technicalities to conclude that the constitutionality of the ordinance as construed and applied to petitioner was not before the Illinois courts. The record makes clear that petitioner at all times challenged the constitutionality of the ordinance as construed and applied to him.

Reversed.

Dennis v. U.S. (1951)

341 U.S. 494 (1951)

Vote: 6-2

Opinion: Vinson, joined by Reed, Burton and Minton

Decision: for the U.S.

Concurring Opinion: Frankfurter

Concurring Opinion: Jackson

Dissenting Opinion: Black

Dissenting Opinion: Douglas

Not participating: Clark

Mr. Chief Justice Vinson announced the judgment of the Court.

Petitioners were indicted in July, 1948, for violation of the conspiracy provisions of the Smith Act, during the period of April, 1945, to July, 1948. The pretrial motion to quash the indictment on the grounds, inter alia, that the statute was unconstitutional was denied. A verdict of guilty as to all the petitioners was returned by the jury. The Court of Appeals affirmed the convictions. We granted certiorari, limited to the following two questions: (1) Whether either § 2 or § 3 of the Smith Act, inherently or as construed and applied in the instant case, violates the First Amendment and other provisions of the Bill of Rights; (2) whether either § 2 or § 3 of the Act, inherently or as construed and applied in the instant case, violates the First and Fifth Amendments because of indefiniteness.

Sections 2 and 3 of the Smith Act, 54 Stat. 671, 18 U. S. C. (1946 ed.) §§ 10, 11 (see present 18 U. S. C. § 2385), provide as follows:

“SEC. 2. (a) It shall be unlawful for any person—

“(1) to knowingly or willfully advocate, abet, advise, or teach the duty, necessity, desirability, or propriety of overthrowing or destroying any government in the United States by force or violence, or by the assassination of any officer of any such government;

“(2) with intent to cause the overthrow or destruction of any government in the United States, to print, publish, edit, issue, circulate, sell, distribute, or publicly display any written or printed matter advocating, advising, or teaching the duty, necessity, desirability, or propriety of overthrowing or destroying any government in the United States by force or violence;

“(3) to organize or help to organize any society, group, or assembly of persons who teach, advocate, or encourage the overthrow or destruction of any government in the United States by force or violence; or to be or become a member of, or affiliate with, any such society, group, or assembly of persons, knowing the purposes thereof.

“(b) For the purposes of this section, the term `government in the United States’ means the Government of the United States, the government of any State, Territory, or possession of the United States, the government of the District of Columbia, or the government of any political subdivision of any of them.

“SEC. 3. It shall be unlawful for any person to attempt to commit, or to conspire to commit, any of the acts prohibited by the provisions of this title.”

The indictment charged the petitioners with willfully and knowingly conspiring (1) to organize as the Communist Party of the United States of America a society, group and assembly of persons who teach and advocate the overthrow and destruction of the Government of the United States by force and violence, and (2) knowingly and willfully to advocate and teach the duty and necessity of overthrowing and destroying the Government of the United States by force and violence. The indictment further alleged that § 2 of the Smith Act proscribes these acts and that any conspiracy to take such action is a violation of § 3 of the Act.

The trial of the case extended over nine months, six of which were devoted to the taking of evidence, resulting in a record of 16,000 pages … Whether, on this record, the petitioners did, in fact advocate the overthrow of the Government … is not before us, and we must base any discussion of this point upon the conclusions states in the opinion in the Court of Appeals … That court held the record in this case amply supports the necessary finding of the jury that petitioners, were unwilling to work within our framework of democracy …

…

The obvious purpose of the statute is to protect existing Government not from change by peaceable, lawful and constitutional means, but from change by violence, revolution and terrorism. That it is within the power of the Congress to protect the Government of the United States from armed rebellion is a proposition which requires little discussion. Whatever theoretical merit there may be to the argument that there is a “right” to rebellion against dictatorial governments is without force where the existing structure of the government provides for peaceful and orderly change. We reject any principle of governmental helplessness in the face of preparation for revolution, which principle, carried to its logical conclusion, must lead to anarchy. No one could conceive that it is not within the power of Congress to prohibit acts intended to overthrow the Government by force and violence. The question with which we are concerned here is not whether Congress has such power, but whether the means which it has employed conflict with the First and Fifth Amendments to the Constitution.

One of the bases for the contention that the means which Congress has employed are invalid takes the form of an attack on the face of the statute on the grounds that, by its terms, it prohibits academic discussion of the merits of Marxism-Leninism, that it stifles ideas and is contrary to all concepts of a free speech and a free press.

… The very language of the Smith Act negates the interpretation which petitioners would have us impose on that Act. It is directed at advocacy, not discussion. Thus, the trial judge properly charged the jury that they could not convict if they found that petitioners did “no more than pursue peaceful studies and discussions or teaching and advocacy in the realm of ideas.” He further charged that it was not unlawful “to conduct in an American college or university a course explaining the philosophical theories set forth in the books which have been placed in evidence.” Such a charge is in strict accord with the statutory language, and illustrates the meaning to be placed on those words. Congress did not intend to eradicate the free discussion of political theories, to destroy the traditional rights of Americans to discuss and evaluate ideas without fear of governmental sanction. Rather Congress was concerned with the very kind of activity in which the evidence showed these petitioners engaged.

But although the statute is not directed at the hypothetical cases which petitioners have conjured, its application in this case has resulted in convictions for the teaching and advocacy of the overthrow of the Government by force and violence, which, even though coupled with the intent to accomplish that overthrow, contains an element of speech. For this reason, we must pay special heed to the demands of the First Amendment marking out the boundaries of speech …

No important case involving free speech was decided by this Court prior to Schenck v. United States (1919). Indeed, the summary treatment accorded an argument based upon an individual’s claim that the First Amendment protected certain utterances indicates that the Court at earlier dates placed no unique emphasis upon that right. It was not until the classic dictum of Justice Holmes in the Schenck Case that speech per se received that emphasis in a majority opinion …

The next important case before the Court in which free speech was the crux of the conflict was Gitlow v. New York (1925) … Its reasoning was as follows: The “clear and present danger” test was applied to the utterance itself in Schenck because the question was merely one of sufficiency of evidence under an admittedly constitutional statute. Gitlow, however, presented a different question. There a legislature had found that a certain kind of speech was, itself, harmful and unlawful. The constitutionality of such a state statute had to be adjudged by this Court just as it determined the constitutionality of any state statute, namely, whether the statute was “reasonable.” Since it was entirely reasonable for a state to attempt to protect itself from violent overthrow, the statute was perforce reasonable. The only question remaining in the case became whether there was evidence to support the conviction, a question which gave the majority no difficulty. Justices Holmes and Brandeis refused to accept this approach, but insisted that wherever speech was the evidence of the violation, it was necessary to show that the speech created the “clear and present danger” of the substantive evil which the legislature had the right to prevent …

… [T]here is little doubt that subsequent opinions have inclined toward the Holmes-Brandeis rationale … But we further suggested that neither Justice Holmes nor Justice Brandeis ever envisioned that a shorthand phrase should be crystallized into a rigid rule to be applied inflexibly without regard to the circumstances of each case. Speech is not an absolute, above and beyond control by the legislature when its judgment, subject to review here, is that certain kinds of speech are so undesirable as to warrant criminal sanction. Nothing is more certain in modern society than the principle that there are no absolutes, that a name, a phrase, a standard has meaning only when associated with the considerations which gave birth to the nomenclature. To those who would paralyze our Government in the face of impending threat by encasing it in a semantic straitjacket we must reply that all concepts are relative.

In this case we are squarely presented with the application of the “clear and present danger” test, and must decide what that phrase imports. We first note that many of the cases in which this Court has reversed convictions by use of this or similar tests have been based on the fact that the interest which the State was attempting to protect was itself too insubstantial to warrant restriction of speech. * * * Overthrow of the Government by force and violence is certainly a substantial enough interest for the Government to limit speech. Indeed, this is the ultimate value of any society, for if a society cannot protect its very structure from armed internal attack, it must follow that no subordinate value can be protected. If, then, this interest may be protected, the literal problem which is presented is what has been meant by the use of the phrase “clear and present danger” of the utterances bringing about the evil within the power of Congress to punish.

Obviously, the words cannot mean that before the Government may act, it must wait until the putsch is about to be executed, the plans have been laid and the signal is awaited. If Government is aware that a group aiming at its overthrow is attempting to indoctrinate its members and to commit them to a course whereby they will strike when the leaders feel the circumstances permit, action by the Government is required … Certainly an attempt to overthrow the Government by force, even though doomed from the outset because of inadequate numbers of power of the revolutionists, is a sufficient evil for Congress to prevent. The damage which such attempts create both physically and politically to a nation makes it impossible to measure the validity in terms of the probability of success, or the immediacy of a successful attempt … We must therefore reject the contention that success or probability of success is the criterion.

… It is the existence of the conspiracy which creates the danger. If the ingredients of the reaction are present, we cannot bind the Government to wait until the catalyst is added.

Affirmed.

Mr. Justice Frankfurter, concurring in affirmance of the judgment.

… But even the all-embracing power and duty of self-preservation are not absolute. Like the war power, which is indeed an aspect of the power of self-preservation, it is subject to applicable constitutional limitations. Our Constitution has no provision lifting restrictions upon governmental authority during periods of emergency, although the scope of a restriction may depend on the circumstances in which it is invoked.

The First Amendment is such a restriction. It exacts obedience even during periods of war; it is applicable when war clouds are not figments of the imagination no less than when they are.

… The right of a man to think what he pleases, to write what he thinks, and to have his thoughts made available for others to hear or read has an engaging ring of universality. The Smith Act and this conviction under it no doubt restrict the exercise of free speech and assembly. Does that, without more, dispose of the matter?

Just as there are those who regard as invulnerable every measure for which the claim of national survival is invoked, there are those who find in the Constitution a wholly unfettered right of expression. Such literalness treats the words of the Constitution as though they were found on a piece of outworn parchment instead of being words that have called into being a nation with a past to be preserved for the future. * * *

The language of the First Amendment is to be read not as barren words found in a dictionary but as symbols of historic experience illuminated by the presuppositions of those who employed them. Not what words did Madison and Hamilton use, but what was it in their minds which they conveyed? Free speech is subject to prohibition of those abuses of expression which a civilized society may forbid. As in the case of every other provision of the Constitution that is not crystallized by the nature of its technical concepts, the fact that the First Amendment is not self-defining and self-enforcing neither impairs its usefulness nor compels its paralysis as a living instrument.

… The demands of free speech in a democratic society as well as the interest in national security are better served by candid and informed weighing of the competing interests, within the confines of the judicial process, than by announcing dogmas too inflexible for the non-Euclidian problems to be solved.

But how are competing interests to be assessed? Since they are not subject to quantitative ascertainment, the issue necessarily resolves itself into asking, who is to make the adjustment?—who is to balance the relevant factors and ascertain which interest is in the circumstances to prevail? Full responsibility for the choice cannot be given to the courts. Courts are not representative bodies. They are not designed to be a good reflex of a democratic society. Their judgment is best informed, and therefore most dependable, within narrow limits. Their essential quality is detachment, founded on independence. History teaches that the independence of the judiciary is jeopardized when courts become embroiled in the passions of the day and assume primary responsibility in choosing between competing political, economic and social pressures.

… But in no case has a majority of this Court held that a legislative judgment, even as to freedom of utterance, may be overturned merely because the Court would have made a different choice between the competing interests had the initial legislative judgment been for it to make … Even though advocacy of overthrow deserves little protection, we should hesitate to prohibit it if we thereby inhibit the interchange of rational ideas so essential to representative government and free society …

Mr. Justice Black, dissenting.

* * * At the outset I want to emphasize what the crime involved in this case is, and what it is not. These petitioners were not charged with an attempt to overthrow the Government. They were not charged with overt acts of any kind designed to overthrow the Government. They were not even charged with saying anything or writing anything designed to overthrow the Government. The charge was that they agreed to assemble and to talk and publish certain ideas at a later date: The indictment is that they conspired to organize the Communist Party and to use speech or newspapers and other publications in the future to teach and advocate the forcible overthrow of the Government. No matter how it is worded, this is a virulent form of prior censorship of speech and press, which I believe the First Amendment forbids. I would hold § 3 of the Smith Act authorizing this prior restraint unconstitutional on its face and as applied.

… The opinions for affirmance indicate that the chief reason for jettisoning the rule is the expressed fear that advocacy of Communist doctrine endangers the safety of the Republic. Undoubtedly, a governmental policy of unfettered communication of ideas does entail dangers. To the Founders of this Nation, however, the benefits derived from free expression were worth the risk. They embodied this philosophy in the First Amendment’s command that “Congress shall make no law … abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press. …” I have always believed that the First Amendment is the keystone of our Government, that the freedoms it guarantees provide the best insurance against destruction of all freedom. At least as to speech in the realm of public matters, I believe that the “clear and present danger” test does not “mark the furthermost constitutional boundaries of protected expression” but does “no more than recognize a minimum compulsion of the Bill of Rights.”

…

Public opinion being what it now is, few will protest the conviction of these Communist petitioners. There is hope, however, that in calmer times, when present pressures, passions and fears subside, this or some later Court will restore the First Amendment liberties to the high preferred place where they belong in a free society.

Feiner v. People of the State of New York (1951)

340 U.S. 315 (1951)

Vote: 6-3

Decision: for the State of New York

Majority: Vinson, joined by Reed, Jackson, Burton, Clark and Minton

Concurring: Frankfurter

Dissent: Black

Dissent: Douglas joined by Minton

Mr. Chief Justice VINSON delivered the opinion of the Court.

Petitioner was convicted of the offense of disorderly conduct, a misdemeanor under the New York penal laws … and was sentenced to thirty days in the county penitentiary. The conviction was affirmed by the Onondaga County Court and the New York Court of Appeals … The case is here on certiorari … petitioner having claimed that the conviction is in violation of his right of free speech under the Fourteenth Amendment.

… On the evening of March 8, 1949, petitioner Irving Feiner was addressing an open-air meeting … At approximately 6:30 p.m., the police received a telephone complaint concerning the meeting, and two officers were detailed to investigate. One of these officers went to the scene immediately, the other arriving some twelve minutes later. They found a crowd of about seventy-five or eighty people, both Negro and white, filling the sidewalk and spreading out into the street. Petitioner, standing on a large wooden box on the sidewalk, was addressing the crowd through a loud-speaker system attached to an automobile. Although the purpose of his speech was to urge his listeners to attend a meeting to be held that night in the Syracuse Hotel, in its course he was making derogatory remarks concerning President Truman, the American Legion, the Mayor of Syracuse, and other local political officials.

The police officers made no effort to interfere with petitioner’s speech, but were first concerned with the effect of the crowd on both pedestrian and vehicular traffic. They observed the situation from the opposite side of the street, noting that some pedestrians were forced to walk in the street to avoid the crowd. Since traffic was passing at the time, the officers attempted to get the people listening to petitioner back on the sidewalk. The crowd was restless and there was some pushing, shoving and milling around. One of the officers telephoned the police station from a nearby store, and then both policemen crossed the street and mingled with the crowd without any intention of arresting the speaker.

At this time, petitioner was speaking in a ‘loud, high-pitched voice.’ He gave the impression that he was endeavoring to arouse the Negro people against the whites, urging that they rise up in arms and fight for equal rights. The statements before such a mixed audience ‘stirred up a little excitement.’ Some of the onlookers made remarks to the police about their inability to handle the crowd and at least one threatened violence if the police did not act. There were others who appeared to be favoring petitioner’s arguments. Because of the feeling that existed in the crowd both for and against the speaker, the officers finally ‘stepped in to prevent it from resulting in a fight.’ One of the officers approached the petitioner, not for the purpose of arresting him, but to get him to break up the crowd. He asked petitioner to get down off the box, but the latter refused to accede to his request and continued talking. The officer waited for a minute and then demanded that he cease talking. Although the officer had thus twice requested petitioner to stop over the course of several minutes, petitioner not only ignored him but continued talking. During all this time, the crowd was pressing closer around petitioner and the officer. Finally, the officer told petitioner he was under arrest and ordered him to get down from the box, reaching up to grab him. Petitioner stepped down, announcing over the microphone that ‘the law has arrived, and I suppose they will take over now.’ In all, the officer had asked petitioner to get down off the box three times over a space of four or five minutes. Petitioner had been speaking for over a half hour.

On these facts, petitioner was specifically charged with violation of § 722 of the Penal Law of New York, Mc.K.Consol. Laws, c. 40 … The bill of particulars, demanded by petitioner and furnished by the State, gave in detail the facts upon which the prosecution relied to support the charge of disorderly conduct. Paragraph C is particularly pertinent here: ‘By ignoring and refusing to heed and obey reasonable police orders issued at the time and place mentioned in the Information to regulate and control said crowd and to prevent a breach or breaches of the peace and to prevent injury to pedestrians attempting to use said walk, and being forced into the highway adjacent to the place in question, and prevent injury to the public generally.’

We are not faced here with blind condonation by a state court of arbitrary police action. Petitioner was accorded a full, fair trial. The trial judge heard testimony supporting and contradicting the judgment of the police officers that a clear danger of disorder was threatened. After weighing this contradictory evidence, the trial judge reached the conclusion that the police officers were justified in taking action to prevent a breach of the peace. The exercise of the police officers’ proper discretionary power to prevent a breach of the peace was thus approved by the trial court and later by two courts on review. The courts below recognized petitioner’s right to hold a street meeting at this locality, to make use of loud-speaking equipment in giving his speech, and to make derogatory remarks concerning public officials and the American Legion. They found that the officers in making the arrest were motivated solely by a proper concern for the preservation of order and protection of the general welfare, and that there was no evidence which could lend color to a claim that the acts of the police were a cover for suppression of petitioner’s views and opinions. Petitioner was thus neither arrested nor convicted for the making or the content of his speech. Rather, it was the reaction which it actually engendered.

The language of Cantwell v. State of Connecticut, (1940), is appropriate here.

‘The offense known as breach of the peace embraces a great variety of conduct destroying or menacing public order and tranquility. It includes not only violent acts but acts and words likely to produce violence in others. On one would have the hardihood to suggest that the principle of freedom of speech sanctions incitement to riot or that religious liberty connotes the privilege to exhort others to physical attack upon those belonging to another sect. When clear and present danger of riot, disorder, interference with traffic upon the public streets, or other immediate threat to public safety, peace, or order, appears, the power of the State to prevent or punish is obvious.’

The findings of the New York courts as to the condition of the crowd and the refusal of petitioner to obey the police requests, supported as they are by the record of this case, are persuasive that the conviction of petitioner for violation of public peace, order and authority does not exceed the bounds of proper state police action. This Court respects, as it must, the interest of the community in maintaining peace and order on its streets … We cannot say that the preservation of that interest here encroaches on the constitutional rights of this petitioner.

We are well aware that the ordinary murmurings and objections of a hostile audience cannot be allowed to silence a speaker, and are also mindful of the possible danger of giving overzealous police officials complete discretion to break up otherwise lawful public meetings. ‘A State may not unduly suppress free communication of views, religious or other, under the guise of conserving desirable conditions.’ Cantwell v. State of Connecticut. But we are not faced here with such a situation. It is one thing to say that the police cannot be used as an instrument for the suppression of unpopular views, and another to say that, when as here the speaker passes the bounds of argument or persuasion and undertakes incitement to riot, they are powerless to prevent a breach of the peace. Nor in this case can we condemn the considered judgment of three New York courts approving the means which the police, faced with a crisis, used in the exercise of their power and duty to preserve peace and order.

The findings of the state courts as to the existing situation and the imminence of greater disorder coupled with petitioner’s deliberate defiance of the police officers convince us that we should not reverse this conviction in the name of free speech.

Affirmed.

Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969)

395 U.S. 44 (1969)

Per Curiam

Concurring: Douglas

Concurring: Black

Per Curiam

Opinion for the Court.

The appellant, a leader of a Ku Klux Klan group, was convicted under the Ohio Criminal Syndicalism statute for “advocat[ing] … the duty, necessity, or propriety of crime, sabotage, violence, or unlawful methods of terrorism as a means of accomplishing industrial or political reform” and for “voluntarily assembl[ing] with any society, group, or assemblage of persons formed to teach or advocate the doctrines of criminal syndicalism.” Ohio Rev. Code Ann. § 2923.13. He was fined $1,000 and sentenced to one to 10 years’ imprisonment. The appellant challenged the constitutionality of the criminal syndicalism statute under the First and Fourteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution, but the intermediate appellate court of Ohio affirmed his conviction without opinion … Appeal was taken to this Court, and we noted probable jurisdiction. We reverse.

The record shows that a man, identified at trial as the appellant, telephoned an announcer-reporter on the staff of a Cincinnati television station and invited him to come to a Ku Klux Klan “rally” to be held at a farm in Hamilton County. With the cooperation of the organizers, the reporter and a cameraman attended the meeting and filmed the events. Portions of the films were later broadcast on the local station and on a national network.

The prosecution’s case rested on the films and on testimony identifying the appellant as the person who communicated with the reporter and who spoke at the rally …

One film showed 12 hooded figures, some of whom carried firearms. They were gathered around a large wooden cross, which they burned. No one was present other than the participants and the newsmen who made the film. Most of the words uttered during the scene were incomprehensible when the film was projected, but scattered phrases could be understood that were derogatory of Negroes and, in one instance, of Jews. Another scene on the same film showed the appellant, in Klan regalia, making a speech. The speech, in full, was as follows:

“This is an organizers’ meeting. We have had quite a few members here today which are—we have hundreds, hundreds of members throughout the State of Ohio. I can quote from a newspaper clipping from the Columbus, Ohio Dispatch, five weeks ago Sunday morning. The Klan has more members in the State of Ohio than does any other organization. We’re not a revengent organization, but if our President, our Congress, our Supreme Court, continues to suppress the white, Caucasian race, it’s possible that there might have to be some revengeance taken.

“We are marching on Congress July the Fourth, four hundred thousand strong. From there we are dividing into two groups, one group to march on St. Augustine, Florida, the other group to march into Mississippi. Thank you.”

The second film showed six hooded figures one of whom, later identified as the appellant, repeated a speech very similar to that recorded on the first film. The reference to the possibility of “revengeance” was omitted, and one sentence was added: “Personally, I believe the nigger should be returned to Africa, the Jew returned to Israel.” Though some of the figures in the films carried weapons, the speaker did not.

… [L]ater decisions have fashioned the principle that the constitutional guarantees of free speech and free press do not permit a State to forbid or proscribe advocacy of the use of force or of law violation except where such advocacy is directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action …”the mere abstract teaching … of the moral propriety or even moral necessity for a resort to force and violence, is not the same as preparing a group for violent action and steeling it to such action.” A statute which fails to draw this distinction impermissibly intrudes upon the freedoms guaranteed by the First and Fourteenth Amendments. It sweeps within its condemnation speech which our Constitution has immunized from governmental control.

Measured by this test, Ohio’s Criminal Syndicalism Act cannot be sustained. The Act punishes persons who “advocate or teach the duty, necessity, or propriety” of violence “as a means of accomplishing industrial or political reform”; or who publish or circulate or display any book or paper containing such advocacy; or who “justify” the commission of violent acts “with intent to exemplify, spread or advocate the propriety of the doctrines of criminal syndicalism”; or who “voluntarily assemble” with a group formed “to teach or advocate the doctrines of criminal syndicalism.” Neither the indictment nor the trial judge’s instructions to the jury in any way refined the statute’s bald definition of the crime in terms of mere advocacy not distinguished from incitement to imminent lawless action.

Accordingly, we are here confronted with a statute which, by its own words and as applied, purports to punish mere advocacy and to forbid, on pain of criminal punishment, assembly with others merely to advocate the described type of action. Such a statute falls within the condemnation of the First and Fourteenth Amendments. The contrary teaching of Whitney v. California, cannot be supported, and that decision is therefore overruled.

Reversed.

Note: Wondering if the broadcast of the rallies might have an effect? See Nelson, Thomas E., Rosalee A. Clawson, and Zoe M. Oxley. “Media framing of a civil liberties conflict and its effect on tolerance.” American Political Science Review 91.3 (1997): 567-583.

Hess v. Indiana (1973)

414 U.S. 105 (1973)

Per Curiam Opinion for the Court. Justice Rehnquist Filed a dissenting opinion, in which the Chief Justice and Justice Blackmun joined.

Per Curiam Opinion for the Court.

Gregory Hess appeals from his conviction in the Indiana courts for violating the State’s disorderly conduct statute. Appellant contends that his conviction should be reversed because the statute is unconstitutionally vague, because the statute is overbroad in that it forbids activity that is protected under the First and Fourteenth Amendments, and because the statute, as applied here, abridged his constitutionally protected freedom of speech. These contentions were rejected in the City Court, where Hess was convicted, and in the Superior Court, which reviewed his conviction. The Supreme Court of Indiana, with one dissent, considered and rejected each of Hess’ constitutional contentions, and accordingly affirmed his conviction.

The events leading to Hess’ conviction began with an antiwar demonstration on the campus of Indiana University. In the course of the demonstration, approximately 100 to 150 of the demonstrators moved onto a public street and blocked the passage of vehicles. When the demonstrators did not respond to verbal directions from the sheriff to clear the street, the sheriff and his deputies began walking up the street, and the demonstrators in their path moved to the curbs on either side, joining a large number of spectators who had gathered. Hess was standing off the street as the sheriff passed him. The sheriff heard Hess utter the word “fuck” in what he later described as a loud voice and immediately arrested him on the disorderly conduct charge. It was later stipulated that what appellant had said was “We’ll take the fucking street later,” or “We’ll take the fucking street again.” Two witnesses who were in the immediate vicinity testified, apparently without contradiction, that they heard Hess’ words and witnessed his arrest. They indicated that Hess did not appear to be exhorting the crowd to go back into the street, that he was facing the crowd and not the street when he uttered the statement, that his statement did not appear to be addressed to any particular person or group, and that his tone, although loud, was no louder than that of the other people in the area.

Indiana’s disorderly conduct statute was applied in this case to punish only spoken words. It hardly needs repeating that “[t]he constitutional guarantees of freedom of speech forbid the States to punish the use of words or language not within `narrowly limited classes of speech.'”

The words here did not fall within any of these “limited classes.” In the first place, it is clear that the Indiana court specifically abjured any suggestion that Hess’ words could be punished as obscene … Indeed, after Cohen v. California, such a contention with regard to the language at issue would not be tenable. By the same token, any suggestion that Hess’ speech amounted to “fighting words,” could not withstand scrutiny. Even if under other circumstances this language could be regarded as a personal insult, the evidence is undisputed that Hess’ statement was not directed to any person or group in particular … Thus, under our decisions, the State could not punish this speech as “fighting words.”

…

The Indiana Supreme Court placed primary reliance on the trial court’s finding that Hess’ statement “was intended to incite further lawless action on the part of the crowd in the vicinity of appellant and was likely to produce such action.” At best, however, the statement could be taken as counsel for present moderation; at worst, it amounted to nothing more than advocacy of illegal action at some indefinite future time. This is not sufficient to permit the State to punish Hess’ speech. Under our decisions, “the constitutional guarantees of free speech and free press do not permit a State to forbid or proscribe advocacy of the use of force or of law violation except where such advocacy is directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action.” Brandenburg v. Ohio, (1969). (Emphasis added.) Since the uncontroverted evidence showed that Hess’ statement was not directed to any person or group of persons, it cannot be said that he was advocating, in the normal sense, any action. And since there was no evidence, or rational inference from the import of the language, that his words were intended to produce, and likely to produce, imminent disorder, those words could not be punished by the State on the ground that they had “a `tendency to lead to violence.’

Accordingly, the motion to proceed in forma pauperis granted and the judgment of the Supreme Court of Indiana is reversed.

Mr. Justice Rehnquist, with whom the Chief Justice and Mr. Justice Blackmun join, dissenting.

The Court’s per curiam opinion rendered today aptly demonstrates the difficulties inherent in substituting a different complex of factual inferences for the inferences reached by the courts below. Since it is not clear to me that the Court has a sufficient basis for its action, I dissent.

… The majority makes much of this “uncontroverted evidence,” but I am unable to find anywhere in the opinion an explanation of why it must be believed. Surely the sentence “We’ll take the fucking street later (or again)” is susceptible of characterization as an exhortation, particularly when uttered in a loud voice while facing a crowd. The opinions of two defense witnesses cannot be considered proof to the contrary, since the trial court was perfectly free to reject this testimony if it so desired. Perhaps, as these witnesses and the majority opinion seem to suggest, appellant was simply expressing his views to the world at large, but that is surely not the only rational explanation.

The majority also places great emphasis on appellant’s use of the word “later,” even suggesting at one point that the statement “could be taken as counsel for present moderation.” The opinion continues: “[A]t worst, it amounted to nothing more than advocacy of illegal action at some indefinite future time.” From that observation, the majority somehow concludes that the advocacy was not directed towards inciting imminent action. But whatever other theoretical interpretations may be placed upon the remark, there are surely possible constructions of the statement which would encompass more or less immediate and continuing action against the harassed police. They should not be rejected out of hand because of an unexplained preference for other acceptable alternatives.

The simple explanation for the result in this case is that the majority has interpreted the evidence differently from the courts below. In doing so, however, I believe the Court has exceeded the proper scope of our review. Rather than considering the “evidence” in the light most favorable to the appellee and resolving credibility questions against the appellant, as many of our cases have required, the Court has instead fashioned its own version of events from a paper record, some “uncontroverted evidence,” and a large measure of conjecture. Since this is not the traditional function of any appellate court, and is surely not a wise or proper use of the authority of this Court, I dissent.

Note, 40 years later: https://www.magbloom.com/2014/03/hess-v-indiana-40th-anniversary-of-landmark-free-speech-case-%E2%80%A8and-it-happened-in-bloomington/

Counterman v. Colorado (2023)

600 U.S. ___ (2023)

Vote: 7-2

Decision: Vacated and remanded

Majority: Kagan, joined by Alito, Jackson, Kavanaugh, and Roberts

Concurrence: Sotomayor, joined by Gorsuch (Parts I, II, III-A, and III-B)

Dissent: Barrett, joined by Thomas

Dissent: Thomas

Justice KAGAN delivered the opinion of the Court.

True threats of violence are outside the bounds of First Amendment protection and punishable as crimes. Today we consider a criminal conviction for communications falling within that historically unprotected category. The question presented is whether the First Amendment still requires proof that the defendant had some subjective understanding of the threatening nature of his statements. We hold that it does, but that a mental state of recklessness is sufficient. The State must show that the defendant consciously disregarded a substantial risk that his communications would be viewed as threatening violence. The State need not prove any more demanding form of subjective intent to threaten another.

From 2014 to 2016, petitioner Billy Counterman sent hundreds of Facebook messages to C. W., a local singer and musician. The two had never met, and C. W. never responded. In fact, she repeatedly blocked Counterman. But each time, he created a new Facebook account and resumed his contacts. Some of his messages were utterly prosaic… except that they were coming from a total stranger. Others suggested that Counterman might be surveilling C. W…. And most critically, a number expressed anger at C. W. and envisaged harm befalling her: “Fuck off permanently.” “Staying in cyber life is going to kill you.” “You’re not being good for human relations. Die.”

The messages put C. W. in fear and upended her daily existence. She believed that Counterman was “threat[ening her] life”; “was very fearful that he was following” her; and was “afraid [she] would get hurt.” …. She stopped walking alone, declined social engagements, and canceled some of her performances, though doing so caused her financial strain. Eventually, C. W. decided that she had to contact the authorities.

Colorado charged Counterman under a statute making it unlawful to “[r]epeatedly . . . make[ ] any form of communication with another person” in “a manner that would cause a reasonable person to suffer serious emotional distress and does cause that person . . . to suffer serious emotional distress.”….

Counterman moved to dismiss the charge on First Amendment grounds, arguing that his messages were not “true threats” and therefore could not form the basis of a criminal prosecution. In line with Colorado law, the trial court assessed the true-threat issue using an “objective ‘reasonable person’ standard.” People v. Cross (Colo. 2006). Under that standard, the State had to show that a reasonable person would have viewed the Facebook messages as threatening…. The court decided, after “consider[ing] the totality of the circumstances,” that Counterman’s statements “r[o]se to the level of a true threat.”…. The court accordingly sent the case to the jury, which found Counterman guilty as charged.

The Colorado Court of Appeals affirmed…. Using the established objective standard, the court then approved the trial court’s ruling that Counterman’s messages were “true threats” and so were not protected by the First Amendment. The Colorado Supreme Court denied review.

Courts are divided about (1) whether the First Amendment requires proof of a defendant’s subjective mindset in true-threats cases, and (2) if so, what mens rea standard is sufficient. We therefore granted certiorari.