The Strategy Diamond

All organizations have strategies. The real question for a business is not whether it has a strategy but rather whether its strategy is effective or ineffective, and whether the elements of the strategy are chosen by managers, luck, or by default. You have probably heard the saying, “luck is a matter of being in the right place at the right time”—well, the key to making sure you are in the right place at the right time is preparation, and in many ways, strategizing provides that type of preparation. Luck is not a bad thing. The challenge is to recognize luck when you see it, capitalize on luck, and put the organization repeatedly in luck’s path.

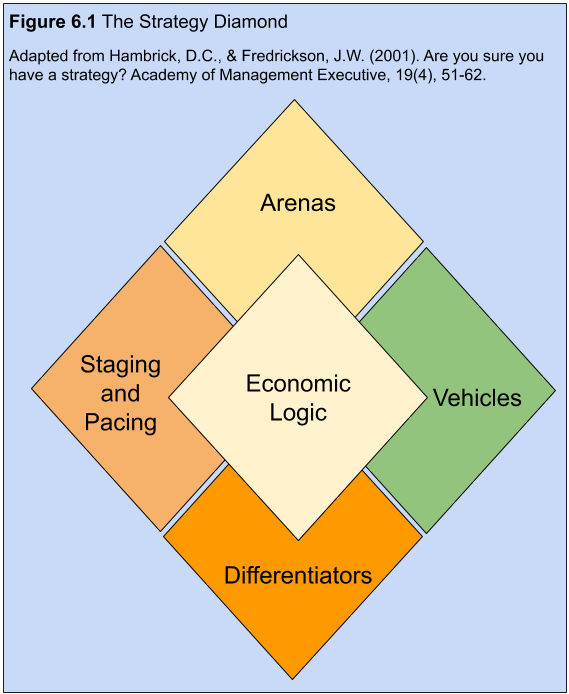

The strategy diamond (Figure 6.1) was developed by strategy researchers Don Hambrick and Jim Fredrickson as a framework for checking and communicating a strategy.[1] Unit 5 discussed the need for focus and choice with strategy, but you might also have noticed that generic strategies and value disciplines do not spell out a strategy’s ingredients. In critiquing the field of strategy, these researchers noted that “after more than 30 years of hard thinking about strategy, consultants and scholars have provided executives with an abundance of frameworks for analyzing strategic situations. Missing, however, has been any guidance as to what the product of these tools should be—or what actually constitutes a strategy.”

Because of their critique and analysis, they concluded that if an organization must have a strategy, then the strategy must necessarily have parts. Figure 6.1 identifies the parts of their diamond model. The diamond model does not presuppose that any particular theory should dictate the contents of each facet. Instead, a strategy consists of an integrated set of choices, but it isn’t a catchall for every important choice a manager faces. In this section, we will tell you a bit about each facet, addressing first the traditional strategy facets of arenas, differentiators, and economic logic; then we will discuss vehicles and finally the staging and pacing facet.

We refer to the first three facets of the strategy diamond—arenas, differentiators, and economic logic—as traditional in the sense that they address three longstanding hallmarks of strategizing. Specifically, strategy matches up market needs and opportunities (located in arenas) with unique features of the firm (shown by its differentiators) to yield positive performance (economic logic). While performance is typically viewed in financial terms, it can have social or environmental components as well.

Arenas

Strategy questions about arenas tell managers and employees where the firm will be active and with how much emphasis.

- Which product categories?

- Which channels?

- Which market segments?

- Which geographic areas?

- Which core technologies?

- Which value-creation strategies?

Beyond geographic-market and product-market arenas, an organization can also make choices about the value-chain arenas in its strategy. To emphasize the choice part of this value-chain arena, Nike’s competitor New Balance manufactures nearly all the athletic shoes that it sells in the United States. Thus, these two sports-shoe companies compete in similar geographic- and product-market arenas but differ greatly in terms of their choice of value-chain arenas.

Example 6.1 Arenas

Nike is headquartered near Beaverton, Oregon. Today, Nike’s geographic market arenas are most major markets around the globe, but in the early 1960s, Nike’s arenas were limited to Pacific Northwest track meets accessible by founder Phil Knight’s car. In terms of product markets (another part of where), the young Nike company (previously Blue Ribbon Sports) sold only track shoes and not even shoes it manufactured.

Earn credit, add your own example!

Differentiators

These are the things that are unique to the firm such that they give it a competitive advantage in its current and future arenas. Differentiators are concerned with the question, how will the firm win?

- Image?

- Customization?

- Price?

- Styling?

- Product reliability?

- Speed to market?

A differentiator could be asset based, that is, it could be something related to an organization’s tangible or intangible assets. A tangible asset has a value and physically exists. Land, machines, equipment, automobiles, and even currencies, are examples of tangible assets. For instance, the oceanfront land on California’s Monterey Peninsula, where the Pebble Beach Golf Course and Resort is located, is a differentiator for it in the premium golf-course market. An intangible asset is a nonphysical resource that provides gainful advantages in the marketplace. Brands, copyrights, software, logos, patents, goodwill, and other intangible factors afford name recognition for products and services. Differentiators can also be found in capabilities, that is, how the organization does something. Walmart, for instance, is very good at keeping its costs low.

Example 6.2 Differentiators

Nike brand has become a valuable intangible asset because of the broad awareness and reputation for quality and high performance that it has built. Nike focuses on developing leading-edge, high-performance athletic technologies, as well as up-to-the-minute fashion in active sportswear.

Earn credit, add your own example!

Economic Logic

This explains how the firm makes money above its cost of capital.

- Lowest costs through scale advantages?

- Lowest costs through scope and replication advantages?

- Premium prices due to unmatchable service?

- Premium prices due to proprietary product features?

While economic logic can include environmental and social profits (benefits reaped by society), the strategy must earn enough financial profits to keep investors (owners, taxpayers, governments, and so on) willing to continue to fund the organization’s costs of doing business. A firm performs well (i.e., has a strong, positive economic logic) when its differentiators are well-aligned with its chosen arenas.

Example 6.3 Economic Logic

The collapse in the late 1990s of stock market valuations for Internet companies lacking in profits—or any prospect of profits—marked a return to economic reality. Profits above the firm’s cost of capital are required to yield sustained or longer-term shareholder returns.

Earn credit, add your own example!

Vehicles

You can see why the first three facets of the strategy diamond—arenas, differentiators, and economic logic—might be considered the traditional facets of strategizing in that they cover the basics: (1) external environment, (2) internal organizational characteristics, and (3) some fit between them that has positive performance consequences. The fourth facet of the strategy diamond is called vehicles. If arenas and differentiators show where you want to go, then vehicles communicate how the strategy will get you there.

- Internal development?

- Joint ventures?

- Licensing/franchising?

- Alliances?

- Acquisitions?

Example 6.4 Vehicles – Joint Venture

Toyota and Mazda have established a new joint venture company. The companies will jointly open an assembly plant in Alabama, each company will contribute equal funding (50/50 joint venture). Because of the need to adapt quickly market conditions, Toyota and Mazda want to increase plant flexibility. The new plant in Alabama can produce 300,000 vehicles per year; Mazda plans to produce 150,000 crossover models and Toyota will manufacture 150,000 Toyota Corollas. Both models will share drivetrains. The collaboration is expected to help the companies reduce their cost of manufacturing and maintaining sustainable growth in “the future of mobility.”

Source: Automotive News, Toyota, Mazda will launch $1.6 billion Alabama plant construction next month, Kim Duong, 2018Fa

Specifically, vehicles refer to how you might pursue a new arena through internal means, through help from a new partner or some other outside source, or even through acquisition. In the context of vehicles, this is where you determine whether your organization is going to grow organically, through acquisition, or a combination of both. Organic growth is the growth rate of a company excluding any growth from takeovers, acquisitions, or mergers. Acquisitive growth, in contrast, refers precisely to any growth from takeovers, acquisitions, or mergers.

Example 6.5 Vehicles – Coopetition

LinkedIn cooperates with employment recruiters because their presence increases the attractiveness of the professional-oriented social network even though it denies LinkedIn a potential source of revenue. This relationship works — even though each would arguably like to control the entire market themselves — because their working together creates a bigger market than working in competition.

Earn credit, add your own example!

A third type of growth can occur through partnership-based relationships, referred to as co-opetition. The term co-opetition is the reference to an organization cooperating with others, even some competitors, in order to grow together.

Vehicles are considered part of the strategy because there are different skills and competencies associated with different vehicles. For instance, acquisitions fuel rapid growth, but they are challenging to negotiate and put into place. Similarly, alliances are a great way to spread the risk and let each partner focus on what it does best. But at the same time, to grow through alliances also means that you must be really good at managing relationships in which you are dependent on another organization over which you do not have direct control. Organic growth, particularly for firms that have grown primarily through partnering or acquisition, has its own distinct challenges, such as the fact that the organization is on its own to put together everything it needs to fuel its growth.

Example 6.6 Vehicles – Acquisition

The software company, SAP, will acquire Qualtrics for $8 billion in cash. Importantly, the chief executive of Qualtrics, Ryan Smith, will continue his position after the acquisition. This indicates that SAP wants to maintain Qualtrics’ organizational culture to avoid the risk of upsetting employees and to avoid the cost of hiring or training new employees. The acquisition will also help SAP gain Qualtrics’ core competency, experienced employees, and market share without the risk of entering a new market. Qualtrics possesses experience data which can benefit SAP by accelerating its market position.

Source: New York Times, Why SAP’s Purchase of Qualtrics May Be Mutually Beneficial, Kim Duong, 2018Fa

Staging and Pacing

Staging and pacing constitute the fifth and final facet of the strategy diamond and answer what will be our speed and sequence of moves?

Staging and pacing reflect the sequence and speed of strategic moves. This powerful facet of strategizing helps you think about timing and next steps, instead of creating a strategy that is a static, monolithic plan. Remember, strategizing is about making choices, and sequencing and speed should be key choices along with the other facets of the strategy. The staging and pacing facet also helps to reconcile the designed and emergent portions of your strategy.

Example 6.7 Staging and Pacing

The management of Chuy’s, a chain of Austin, Texas-based Tex-Mex restaurants, wanted to grow the business outside of Austin, but at the same time, they knew it would be hard to manage these restaurants that were farther away. How should they identify in which cities to experiment with new outlets? Their creative solution was to choose cities that were connected to Austin by Southwest Airlines. Since Southwest is inexpensive and its point-to-point system means that cities are never much more than an hour apart, the Austin managers could easily and regularly visit their new ventures out of town.

Earn credit, add your own example!

- Hambrick, D. C., & Fredrickson, J. W. (2001). Are you sure you have a strategy? Academy of Management Executive, 19(4), 51–62. ↵