Intended and Realized Strategies

The best-laid plans of mice and men often go awry.

~Robert Burns, “To a Mouse,” 1785

This quote from English poet Robert Burns is especially applicable to strategy. While we have been discussing strategy and strategizing as if they were the outcome of a rational, predictable, analytical process, your own experience should tell you that a fine plan does not guarantee a fine outcome. Many things can happen between the development of the plan and its realization, including (but not limited to): (1) the plan is poorly constructed, (2) competitors undermine the advantages envisioned by the plan, or (3) the plan was good but poorly executed. You can probably imagine a number of other factors that might undermine a strategic plan and the results that follow.

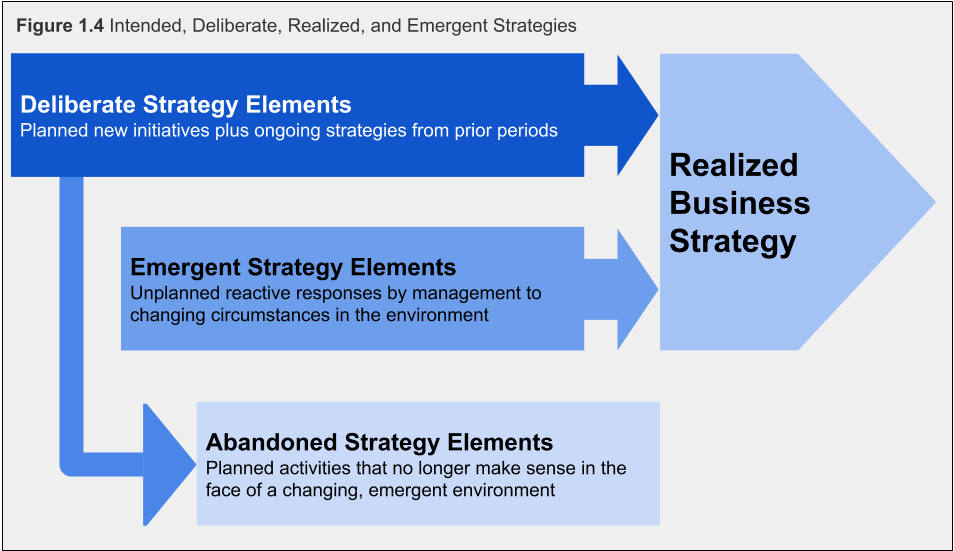

The ways in which organizations make strategy has emerged as an area of intense debate within the strategy field. Henry Mintzberg and his colleagues at McGill University distinguish intended, deliberate, realized, and emergent strategies.[1] These four different aspects of strategy are summarized in Figure 1.4. Intended strategy is strategy as conceived by the top management team. Even here, rationality is limited and the intended strategy is the result of a process of negotiation, bargaining, and compromise, involving many individuals and groups within the organization. However, realized strategy—the actual strategy that is implemented—is only partly related to that which was intended (Mintzberg suggests only 10%–30% of intended strategy is realized).

Example 1.7 – Realized Strategy

Analysis of Honda’s successful entry into the U.S. motorcycle market has provided a battleground for the debate between those who view strategy making as primarily a rational, analytical process of deliberate planning (the design school) and those that envisage strategy as emerging from a complex process of organizational decision making (the emergence or learning school).

Earn credit, add your own example!

The primary determinant of realized strategy is what Mintzberg terms emergent strategy—the decisions that emerge from the complex processes in which individual managers interpret the intended strategy and adapt to changing external circumstances.[2] Thus, the realized strategy is a consequence of deliberate and emerging factors.

Although the debate between the two schools continues,[3] we hope that it is apparent that the central issue is not, “Which school is right?” but, “How can the two views complement one another to give us a richer understanding of strategy making?” Let us explore these complementarities in relation to the factual question of how strategies are made and the normative question of how strategies should be made.

The Making of Strategy

How Is Strategy Made?

Robert Grant, author of Contemporary Strategy Analysis, shares his view on how strategy is made as follows.[4] For most organizations, strategy making combines design and emergence. The deliberate design of strategy (through formal processes such as board meetings and strategic planning) has been characterized as a primarily top-down process. Emergence has been viewed as the result of multiple decisions at many levels, particularly within middle management, and has been viewed as a bottom-up process. These processes may interact in interesting ways.

Example 1.8 – Emergent Strategy

At Intel, the key historic decision to abandon memory chips and concentrate on microprocessors was the result of a host of decentralized decisions taken at divisional and plant level that were subsequently acknowledged by top management and promulgated as strategy.

Earn credit, add your own example!

In practice, both design and emergence occur at all levels of the organization. The strategic planning systems of large companies involve top management passing directives and guidelines down the organization and the businesses passing their draft plans up to corporate. Similarly, emergence occurs throughout the organization—opportunism by CEOs is probably the single most important reason why realized strategies deviate from intended strategies. What we can say for sure is that the role of emergence relative to design increases as the business environment becomes increasingly volatile and unpredictable.

Organizations that inhabit relatively stable environments—the Roman Catholic Church and national postal services—can plan their strategies in some detail. Organizations whose environments cannot be forecasted with any degree of certainty—a gang of car thieves or a construction company located in the Gaza Strip—can establish only a few strategic principles and guidelines; the rest must emerge as circumstances unfold.

What’s the Best Way to Make Strategy?

Mintzberg’s advocacy of strategy making as an iterative process involving experimentation and feedback is not necessarily an argument against the rational, systematic design of strategy. The critical issues are, first, determining the balance of design and emergence and, second, how to guide the process of emergence. The strategic planning systems of most companies involve a combination of design and emergence. Thus, headquarters sets guidelines in the form of vision and mission statements, business principles, performance targets, and capital expenditure budgets. However, within the strategic plans that are decided, divisional and business unit managers have considerable freedom to adjust, adapt, and experiment.

- Mintzberg, H. (1987, July–August). Crafting strategy. Harvard Business Review, pp. 66–75; Mintzberg, H. (1996). The entrepreneurial organization. In H. Mintzberg & J. B. Quinn (Eds.),The strategy process (3rd ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; Mintzberg, H., & Waters, J. A. (1985). Of strategies, deliberate and emergent. Strategic Management Journal, 6, 257–272. ↵

- See Mintzberg, H. Patterns in strategy formulation. (1978). Management Science, 24, 934–948; Mintzberg, H., & Waters, J. A. (1985). Of strategies, deliberate and emergent. Strategic Management Journal, 6, 257–272. (1985); and Mintzberg, H. (1988). Mintzberg on management: Inside our strange world of organizations. New York: Free Press. ↵

- For further debate of the Honda case, see Mintzberg, H., Pascale, R. T., Goold, M., & Rumelt, Richard P. (1996, Summer). The Honda effect revisited. California Management Review, 38, 78–117. ↵

- Grant, R. M. (2002). Contemporary strategy analysis (4th ed., pp. 25–26). New York: Blackwell. 12. [6] Burgelman, R. A., & Grove, A. (1996, Winter). Strategic dissonance. California Management Review, 38, 8–28. ↵