Actors in the Judicial Process

3 On Remand

Legal Strategies After Supreme Court Losses

Richard S. Price

Supreme Court Losses and Strategic Reactions

Law and courts research often overlooks an important question: What do lawyers do after an adverse decision? Law and courts research is dominated by a concern with winning. This naturally comes with considerations of loss, but only as the other side of a dichotomous variable. When we ask whether justices decide issues based on law, policy, strategy, or some combination (Epstein and Knight 1998; Graber 2006; Segal and Spaeth 2002), we are naturally asking what helps some parties win. The debate over legal efficacy assumes victory is a key condition; if courts reject a legal claim, it would appear pointless to then inquire over whether victory has value. So winning is the key variable, and subsequent questions tend to focus on the components of winning or their effects. Here, I take a different tack. The goal here is to understand what strategies lawyers adopt when they face the worst-case scenario: a Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) loss. As developed below, I argue that a SCOTUS loss, while certainly suboptimal, is not always the end of the case. Lawyers strategically develop legal arguments based on the signals sent by courts over time. When the signal changes dramatically from SCOTUS, strategic litigators on remand to the state’s highest court work to salvage their case by turning to state constitutional law as a last-ditch effort to preserve a victory.

To some degree, losses define much of the concern of law and courts research in unspoken ways. If we take the common criticism that judicial review is undemocratic (Bickel 1962), it is because the democratic process rejected some argument that becomes the basis for litigation. American government is decentralized and fragmented, giving losers in one venue many opportunities to thwart their opponents’ success. In other words, litigation may serve as a veto point (Krehbiel 1998). Thus when the New York legislature legalized abortion in 1970, and the Oregon people legalized physician-assisted suicide in 1996, their right-to-life opponents went to court to invalidate the democratic action (Price and Keck 2015). This is the classic story of American cause litigation: claimants lose in one venue and move to the courts as a means of mitigating that loss. This of course works in reverse as well. A SCOTUS loss need not be the end of the legal process. For example, J. Mitchell Pickerill (2004, 42) found that in 47 percent of cases of invalidated federal law from 1954 to 1997, Congress responded with either amended or new statutes often designed to reach the same result as the invalidated law. In his reevaluation of the New Deal constitutional crisis, Barry Cushman (1998) concluded that a significant aspect of the crisis involved New Deal legislators and executive branch officials adapting to SCOTUS’s concerns.

Scholars have not ignored the nature of loss in litigation, but they have tended to focus on sociolegal studies of cause litigation more than what we might term regular litigation. Marc Galanter (1974) illustrated the value of strategic settlement for repeat players in the legal system because they avoided cases that might create adverse precedent through loss, a dynamic that Catharine Albiston (1999) developed further through a study of the strategic use of procedural mechanisms to shape the early law of a new federal statute. This line of research helps establish that sometimes, powerful litigants may intentionally “lose” a case, such as through strategic settlement, to preserve a legal environment that suits their long-term interests. The interest here, however, is with the more traditional litigation where we can presume that winning is the goal.

Douglas NeJaime (2011) developed a theory of loss in social movement litigation. Importantly, he looks at how “strategies developed in the wake of loss operate as second-best alternatives—as responses to the failure of the initial tactic” (971). The presumed goal of such litigation, of course, is victory on the group’s policy issue. Having lost, savvy organizers must strategize around their secondary options. For his study of LGBT and Christian conservative activism, NeJaime concluded that “internally, savvy advocates may use litigation loss (1) to construct organizational identity and (2) to mobilize outraged constituents. Externally, these advocates may use litigation loss (1) to appeal to other state actors, including courts and elected officials, through reworked litigation and nonlitigation tactics and (2) to appeal to the public through images of an antimajoritarian judiciary” (947). In a study of loss in prosegregation litigation, Christopher Schmidt (2015, 1199–1212) emphasized how even litigation losses could be turned to support the message of white Southerners as moderate defenders of a legitimate tradition. One key mobilizing aspect of litigation losses is that they are high-profile events that “can act as a lever for legislative counteraction that reverses the legislative action challenge in the lawsuit, or it can instigate legislation that overrules or minimizes the judicial precedent created by the litigation” (Depoorter 2013, 837). One example of this dynamic is the public and legislative response to Kelo v. New London (2005), where the publicity of the Supreme Court’s opinion led nearly all states to put some greater limits on economic development takings (Somin 2015, 135–64).

While social movements may be able to turn losses into public mobilization victories, most litigants are not part of broader social movements. Everyday rights claimants are more concerned with their individual situation than with establishing a favorable precedent for broader social change. A person who believes she was wrongfully convicted has a more traditional goal: to get out of prison. Most lawyers serve these traditional clients, where even if the lawyers have broader goals themselves, the primary goal is to reverse some negative treatment of their client’s rights. A SCOTUS loss is likely to be particularly troubling, as it is often assumed to foreclose any chance of success. As I explore here, strategic lawyers have other options available to them provided by the peculiarities of American federalism.

Due to a quirk of American federalism, state supreme courts have the ability to disregard federal rights retrenchment. While SCOTUS is the final interpreter of federal law, it has no power to interpret state law (Michigan v. Long 1983). As SCOTUS retrenched away from some forms of liberal rights protections in the 1970s and 1980s (Keck 2004), many liberal judges and law professors turned to state constitutional law as a means of preserving liberal policy goals. The most famous example is Justice William Brennan’s (1977) invitation to litigants and state courts to ignore new federal precedents that he saw as undermining the successes of the Warren Court.[1] This led to a new form of judicial federalism: the use of state constitutions to provide rights protections that are separate and beyond the minimal requirements of federal doctrine.

Judicial federalism provides some claimants with a method of salvaging something from a SCOTUS loss. For a strategic litigant, turning to state supreme courts can offer an additional opportunity to win after her case is rejected at the federal level. Judicial federalism is a distinctly second-best alternative for social movements that seek broad national policy (Farole 1998, 21), but for regular litigants, a win is a win. A person whose conviction is reversed because a search was found to be unconstitutional seems unlikely to care about the niceties of legal doctrine that achieved this goal. While judicial federalism is potentially a source of significant state court independence, empirical studies routinely discovered that state courts overwhelmingly relied on federal doctrine in most rights disputes (Beavers and Emmert 2000; Cauthen 2000; Emmert and Truat 1992; Esler 1994; Fino 1987; Latzer 1991). Studies of legal arguments presented to state supreme courts found that without some degree of incentive, lawyers rarely briefed issues of state constitutional rights (Price 2013, 2015, 2017).

This continued dominance of federal constitutional law is unsurprising given the path-dependent nature of law. With the nationalization of constitutional rights law during the Warren Court era, state constitutional law largely disappeared from legal discussions and education. Though they provide significant attention to state-level variation in common law, law schools teach constitutional law as the product of SCOTUS decisions exclusively (Sutton 2009; Williams 1991). Because “courts’ early resolutions of legal issues can become locked-in and resistant to change” (Hathaway 2001, 604–5), the embedding of federal constitutional doctrine to the exclusion of other potential sources of remedy leaves lawyers trained to respond by following the path already broken. Lawrence Friedman (2011) argued that the weak development of state constitutional rights law is directly related to this path dependence. Breaking from this path is difficult. It requires lawyers to support a new path through not only bringing cases for the court to act on (Epp 1998) but also offering ideational support in the form of legal arguments that take state constitutional law seriously (Price 2013). This last form of support is complicated by the lack of a professional community dedicated to supporting state constitutional law strategically (Hollis-Brusky 2015). As most lawyers would find it daunting to “imagine a world in which there is no federal law” and make state claims from scratch (Friesen 2006, 1–64), I argue that lawyers rely on judicial signals before turning to state constitutional rights claims.

The first signal, and the most relevant to this study, comes externally from SCOTUS. When a federal argument is rejected, either reversing or minimizing a rights claim, strategic lawyers have little choice but to turn to alternative state claims. The problem is that they are limited by their training to conceptualizing constitutional law solely in federal doctrinal terms. Thus on remand, these lawyers are likely to engage in SCOTUS avoidance. In essence, these arguments invite the state supreme court to apply the now rejected federal argument under the auspices of state constitutionalism to avoid review. The second signal comes from within a state. Some state supreme courts decided to encourage state constitutional arguments by providing specific guidance or instruction to lawyers (see Price 2013, 2015). The goal of these internal signals is often to overcome the tendency of lawyers to speak in federal terms only. I will illustrate this theory with a case study of George Upton.

The Case of George Upton

On September 11, 1980, an unidentified woman called the Yarmouth, Massachusetts, police department to report that “a motor home full of stolen stuff [is] parked behind the home of [George Upton] and his mother” (Commonwealth v. Upton 1983).[2] Under questioning, the woman described the nature of the goods and said that she had seen them personally at some unspecified time and place. The woman eventually agreed to the officer’s assertion that she was an ex-girlfriend of Upton. After visually confirming that a motor home was on the property, the officer obtained a search warrant based on the information from the phone call. After a variety of stolen items were discovered, Upton was charged with burglary and related crimes. Upton ultimately appealed his conviction to the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts (SJC), arguing that the search warrant was invalid.

Initially, Upton’s lawyers argued a fairly standard Fourth Amendment claim: the warrant affidavit lacked probable cause under Aguilar-Spinelli. In short, this doctrine required that an affidavit demonstrate both the informant’s basis for the knowledge and the veracity of the information (Aguilar v. Texas 1964; Spinelli v. U.S. 1969). Shortly after this brief was filed, SCOTUS decided Illinois v. Gates (1983). The rigid Aguilar-Spinelli test was jettisoned in favor of a more amorphous “totality of the circumstances” test; determinations of probable cause were subjected to a deferential standard of review, where a higher showing of veracity could overcome deficiencies in the informant’s basis for knowledge and vice versa. As this issue implicated the only significant constitutional issue in Upton’s case, the SJC ordered new arguments on the effect of this change.

Upton’s lawyers carefully framed Gates as a minor change at most, but perhaps realizing that this was a shaky argument, they argued a new theory: Article 14 of the Massachusetts Declaration of Rights mandates the continued application of the now discarded federal rule.[3] Despite the fact that the state constitution had been virtually ignored in the first argument, Upton now argued, “It is obviously the province and indeed, the obligation, of [the SJC] to interpret this state’s constitution.”[4] While the brief noted textual differences between the state and federal provision and the prerevolutionary history of the Massachusetts Constitution, the primary argument amounted to an attack on Gates. It cited Justice Brennan’s dissent to show how the Fourth Amendment was being “eviscerated”: “To allow informants to become the oracle of law enforcement agencies is to decimate the Fourth Amendment.”[5] With such decimation becoming a reality at the federal level, the SJC must enforce the prior protective rule under the state provision.

The SJC concluded that Gates only minimally modified Fourth Amendment doctrine and that the warrant affidavit lacked sufficient probable cause. SCOTUS reversed in a short opinion that demonstrated annoyance at the SJC’s distortion of Gates (Massachusetts v. Upton 1984, 732). On remand to the SJC, a third brief now relied solely on the state constitution. The remand brief immediately framed the issue as whether the SJC should “accept or reject two watershed Fourth Amendment decisions of the United States Supreme Court . . . as the model for interpreting” the state search provision.[6] The claimant discussed some of the same textual and historical differences as the supplemental brief in greater detail, but again the primary concern was with attacking the policy of Gates. Relying on law professors’ critiques of the new trend in Fourth Amendment law, the remand brief attacked the logic of Gates as both faulty and a poor basis for a constitutional rule: “The current ‘totality of the circumstances’ test . . . is so vague and formless, and carries with it such extreme risk of confusion and abuse, that it is incapable of protecting the Article 14 rights of the people of” Massachusetts.[7]

George Upton’s story illustrates the theory well. In his initial appeal, he followed the path laid out by decades of Fourth Amendment law. The lawyers had no real reason to expect to need another argument. Only as SCOTUS shifted did they start to present an alternative and, ultimately, exclusive argument around the state constitution. This new argument eventually managed to win after a SCOTUS loss.

Research Design

The focus of this study is on rights claimants who won in a state supreme court,[8] lost on appeal to SCOTUS, and then were heard on remand. While other elements of the litigation process provide information to the courts, the legal briefs are the primary method of influencing appellate courts. I do not consider opposing briefs or amicus curiae briefs, as the focus is on how lawyers respond to losses; thus the claimant’s brief is the most appropriate to explore that question. This resulted in two types of cases. First, remand cases are those where SCOTUS issued a full decision on the merits of the issue reversing the state court’s decision. Second, consideration cases are those where SCOTUS issued a summary reversal and remand to consider the effect of a recent decision. While consideration cases presented a less definitive negative signal about the viability of the rights claim at issue, they are likely to be instances where a recent federal doctrinal change undermined the viability of the claim. I estimated that about sixty cases should have briefs available, and I collected briefs from thirty-three cases for both initial and remand stages, twenty-four reversal and nine consideration cases. My sample includes briefs from fourteen states. Only the issue directly reviewed by the US Supreme Court was included in my remand analysis.

Coding constitutional arguments as either state or federal can be complicated at times, and I followed three basic rules (Price 2013, 340–41; 2015, 1412–13). First, briefs are typically separated into different legal points, and where the point heading or point clearly identifies the argument as either federal or state based alone, then it is coded accordingly. This holds true even in arguments that are presented as solely state constitutional issues but rely heavily on federal cases and doctrines. Second, where the point cites both federal and state constitutional provisions, I follow Farole’s (1998, 33) standard, with the state citation treated as filler where it is simply presented as part of a string cite without any independent development or rationale. However, where the reference to a state provision is accompanied by some kind of supporting argument, even if vague, it is coded as a separate state argument even if it is not included in a separate point. Third, at times an argument fails to specify a constitutional basis for an argument. Instead, a point may simply refer generally to a “right to counsel,” for example, and I examined the precedents offered to determine the coding. Where the precedent is dominated by federal cases, I code the argument as federal. Where the precedent points to state cases primarily, I follow Esler’s (1994) method of examining those decisions, and if the precedents appeared to rely on independent analysis of the state constitution, I code the argument as state based. Given the assumption that federal law will tend to dominate constitutional claims, my rules are intended to err in favor of state coding, where arguments are vaguely presented. Additionally, I coded certain content measures, taking guidance from state constitutional theory (State v. Gunwall 1986; Tarr 1998, 182–83). Ultimately I coded the following elements for their presence or absence: textual differences between constitutions, discussion of state constitutional history, prior state constitutional precedent, examples of judicial federalism from the home state, precedent from other states, examples of judicial federalism from other states, structural arguments, matters of state and local concern, and public attitudes. The total number of factors referenced in an argument is used as a rough idea of the complexity of the legal claim. However, I make no claim that a certain number of these factors makes a “good” argument or that all are strictly “legal”; it is only an indicator of the nonpolicy arguments used by lawyers in state constitutional claims.

Discussion

Aggregate Trends

| Federal Arguments | State Arguments | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Brief | 32 (84%) | 6 (16%) | 38 |

| Remand Brief | 10 (25%) | 30 (75%) | 40 |

| Total | 423678 |

Table 1: Aggregate arguments.

Table 1 demonstrates the expected breakdown in broad terms: state arguments were uncommon until the negative SCOTUS action suggested that lawyers look elsewhere for protection. Six of the thirty-eight arguments at the initial stage were state-based claims, and of these, only two were the primary argument. In the remaining four cases, the state claim was relatively minor and secondary to the federal claim. Only on remand did lawyers tend to discover state constitutional claims. As with George Upton’s case, these state claims were ignored until federal retrenchment forced lawyers to look elsewhere. While a fairly diverse set of issues is present, two areas are dominant: speech (29 percent) and search and seizure (23 percent).

Initial Appeal

The fact that federal claims dominated at the initial appeal is unsurprising. This fits with existing research findings that state constitutional rights claims are relatively rare in both litigant arguments as well as court decisions. Additionally, the structure of this study focuses only on cases where a federal rights claim was viable enough for a state supreme court to sustain it and thus set the stage for SCOTUS review. This is not to say that litigants ignored the existence of state constitutions; in seventeen (53 percent) of the federal arguments, they did cite the state provision. This citation, however, amounted to little more than simply noting the existence of the provision. Litigants in six cases did make clear state constitutional arguments.

In three of these initial state claims, the likely negative trend in federal protection was evident, and thus the arguments sought to provide an alternative path early. The clearest signal of federal retrenchment was present in Pap’s A.M. v. City of Erie (1998) involving a challenge to a local regulation of nude dancing. While the brief argued that decisions from two decades prior suggested a degree of protection, it had to admit that SCOTUS was moving in a different direction given the decision in Barnes v. Glen Theaters (1991) to uphold a substantially similar statute. In barely a page, the claimant acknowledged that Barnes upheld a similar law but stressed that it lacked a majority and detailed how SCOTUS broke into three parts, with the key difference being over how to apply the standard for regulating symbolic conduct. The claimant turned to a recent federal decision holding that the narrowest decision should control and proceeded to argue that the focus of the inquiry then should turn on Erie’s sole focus on the moral disapproval of nude dancing. Realizing that this argument might be a long shot, the claimant turned to a state claim that developed some classic elements of constitutional arguments. This included noting the fact that the Pennsylvania provision predated and influenced the First Amendment, relying on a few recent state decisions expanding some state constitutional protections.[9] The key to this argument, however, turned not on state constitutional law but on the problematic trend toward federal retrenchment:

First Amendment jurisprudence in this area seemed somewhat clear prior to the Supreme Court’s decision in Barnes. Although no opinion in Barnes garnered a majority, the case has muddied First Amendment legal waters. In interpreting the state Constitution, this Court may look to decisions of other state courts as well as to federal court decisions both pre- and post-Barnes. However, the most cogent analysis of nude dancing as protected by freedom of expression is contained in Justice White’s dissenting opinion in Barnes.[10]

The claimant thus invoked avoidance language: SCOTUS has retracted protection, and the state court should resist by applying the logic of the dissenting opinion. More attention is paid to White’s logic than was given to the fractured opinions of the Barnes majority. Utilizing, in part, decisions from Colorado, Oregon, and Washington, the claimant argued that this dissenting opinion provided the better foundation for a state constitutional rule that would treat a nude dancing ordinance as content-based regulation of expression.

Similarly, two other arguments appeared to anticipate federal retrenchment. In State v. Hershberger (1989), the claimant asserted that the application of a vehicle signs requirement infringed on the free exercise rights of the Amish. While SCOTUS had not yet resolved the case that would dramatically limit federal protection (Employment Division v. Smith 1990), the claimant noted that it had recently affirmed a similar Amish religious exemption issue only by an equally divided vote, signaling a deep division on the issue (Jensen v. Quaring 1985). The claimant spent most of the state argument demonstrating that the state court could provide greater protection, that other states had done similarly in a variety of rights areas, and that the textual differences between the state and federal provisions “tends to cut against the strict separation of belief from conduct” under the former.[11] Similarly, in People v. Conyers (1980),[12] the claimant argued a supplementary state claim that impeachment use of silence was unconstitutional, and while the US Supreme Court had not ruled on the precise circumstances involved there, it had shown approval for the similar use of illegally obtained statements.

Both federal retrenchment and state encouragement played a role in State v. Recuenco (2005). The case centered on whether violations of the right to have a jury determine all aspects of the charged crime can be harmless error. SCOTUS had shown a history of embracing harmless-error analysis for various criminal procedure rights, noting that “most constitutional errors can be harmless” (Neder v. U.S. 1999, 8). In addition to this federal retrenchment, the Washington Supreme Court had signaled broad interest in state constitutional law in general (Price 2013) and had issued decisions noting how the state jury provision grants broader protection in some areas. Influenced by these signals from the Washington court, the claimant provided a well-developed independent state argument that stressed the textual differences between the state and federal provisions, the expansive Washington precedent, and structural differences to justify an independent state rule. Apparently, the claimant was so confident that this original state argument was sufficient that on remand, the claim was simply reasserted via reference to the initial appeal.

Interestingly, two initial arguments were solely state based, lacking any federal claim, and ultimately only ended up before SCOTUS through the weaknesses of the state court’s decision. In Witters v. State (1984),[13] the state denied funding for a course of Bible study. Instead of relying on the federal test (Lemon v. Kurtzman 1971), the state[14] justified the decision based solely on the state constitutional Blaine Amendment, which prohibited any public money from paying for a course of religious study.[15] The state relied on a number of Washington Supreme Court decisions imposing a strict prohibition of state aid to religious education under this provision even if such assistance was allowed under the First Amendment.[16] Despite this fact, the Washington Supreme Court proceeded to base its decision on federal doctrine and upheld the denial (Witters v. State, Commission for the Blind 1984). Similarly, in People v. Caballes (2003), the claimant carefully presented only a state claim that a dog sniff during a traffic stop was unconstitutional presumably because the US Supreme Court had rejected similar dog sniffs claims previously (United States v. Place 1983). Unlike Witters, the claimant did rely heavily on federal doctrine for the logic of the argument even though it was careful to avoid reliance on the Fourth Amendment. The Illinois Supreme Court failed to make any clear statement as to the constitutional basis for its decision, and thus SCOTUS assumed jurisdiction. The experiences in these two cases highlight the fact that legal framing alone cannot control how state courts deal with the issue even if it can influence those courts.

The initial stage demonstrates the expected dominance of federal rights doctrine. Only in a few instances were state arguments presented, and nearly always because the writing was on the wall, federal retrenchment seemed likely. In two cases, the state court had signaled some interest in state constitutional doctrine, and this likely contributed to those arguments.

On Remand

As table 1 illustrates, federal arguments were made on remand but at a much lower rate. Nearly all these federal claims came in consideration cases, which is as expected given that SCOTUS issued a remand to consider some new precedent but made no substantive ruling. Typically, these federal claims focused on distinguishing the new precedent. For example, when SCOTUS reversed and remanded the Ohio Supreme Court’s invalidation of a hate crimes enhancement statute in light of Wisconsin v. Mitchell (1993), the claimant’s federal analysis sought to distinguish the Ohio law from that of Wisconsin. The claimant argued that unlike Wisconsin, Ohio only applied its enhancement statute to five crimes, and this fact made the case a content-based statute within fighting words and should be invalidated for the same reason as the law in R.A.V. v. City of St. Paul (1992).[17] Three claimants failed to make a state argument on remand. In one, a consideration case, the claimant simply asserted that the new SCOTUS precedent did not require a different result.[18] Two claimants in reversal cases simply abandoned the issue, with one turning to a nonconstitutional claim around evidentiary law[19] and the other asserting previously undecided federal constitutional issues even though the state claim was not foreclosed until two months after the brief was filed.[20] Every other case on remand not only presented a state claim but relied almost exclusively on state law.

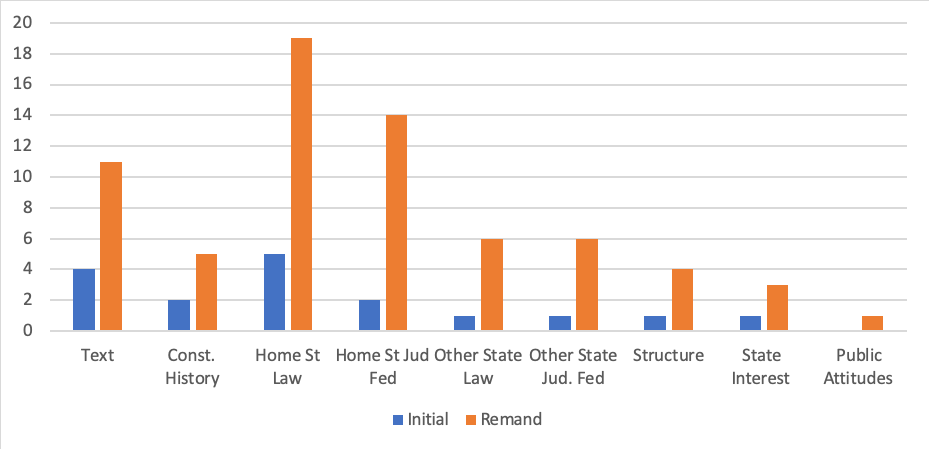

Figure 1 depicts the frequency of types of legal arguments offered to support a state constitutional claim. A number of factors rarely appeared in claimant arguments. For example, only one argument utilized a public attitude claim. A case involving whether funding of religious vocational training violated the state’s establishment clause noted that voters had overwhelmingly rejected a constitutional amendment designed to bring the state constitutional language in line with the federal clause.[21] Similarly, state interest and structure arguments were uncommon. One example of a structural argument came from a Florida case where a man was not informed that an attorney was available to him. On remand, the claimant argued that the federal rule should not be applicable in Florida because prosecutors have unilateral power to file criminal charges and the federal rule would allow them to delay charging a defendant in order to deny access to counsel.[22] Textual difference arguments were found in a relatively large number of arguments, likely because such arguments are relatively easy. State constitutional history, on the other hand, is harder to utilize because such history is not practiced widely or of general knowledge. Such arguments are made primarily where state courts themselves have discussed the history in question. For example, a Wisconsin claimant arguing for the invalidation of the state’s hate crimes law relied heavily on a state justice’s concurring opinion establishing that the textual differences in the state constitution were intended to suggest a broader level of protection.[23] Interestingly, other state law was not commonly discussed.

As lawyers are trained to reason from legal precedents, it is unsurprising that they utilize home state law most frequently. Interestingly, nearly half of the state arguments noted examples of judicial federalism from their state supreme court. By noting their court’s history of rejecting federal law, the claimants likely seek to reassure justices that they will not be doing anything wrong this time. This is particularly important in states where the court has a history of resistance to judicial federalism. For example, all three Ohio remand briefs, where judicial federalism was rare (Tarr and Porter 1988, 124–83; Williams 2009, 197), noted a recent decision interpreting the state’s right-to-bear-arms provision as an individual right.[24] In nearly two-thirds of the state arguments, claimants discussed state decisions on point with the legal issue of concern. A few of these arguments took the form of examples of precedent expanding state protection in the area at issue. For example, in Immuno AG v. Moor-Jankowski (1991),[25] the issue involved constitutional limitations on libel law, and the remand brief noted two examples where the New York Court of Appeals expanded state speech doctrine, one of which specifically related to libel law. Interestingly, both of these precedents were available at the initial stage, but no state claim was made then. Other claimants noted statutory or common-law rules as a means to demonstrate a state law commitment to the more protective rule. Often, the claimant sought to concoct a precedent that supposedly provided a controlling interpretation of the state provision without discussion. One of the clearest examples of this is in Van Arsdall v. State (1987)[26] on the issue of harmless-error analysis from the violation of a defendant’s confrontation rights. The argument rested heavily on a precedent that rejected harmless error in a similar case on federal law grounds but that also cited the state constitutional provision. The claimant presented this cite as creating a controlling state precedent that harmless error was inappropriate regardless of any changes in federal law.

Figure 2 provides a rough complexity measure by totaling the number of legal factors cited by each rights claimant. Two-thirds of the claimants noted two or fewer factors in their state constitutional arguments, with the most common combinations looking to textual differences and home state law, as noted above. Interestingly, of the five briefs to note four or more of the factors, three[27] were cases with a state argument on initial appeal, suggesting that those lawyers may have been better prepared to expand on those arguments than lawyers who had to create a whole new argument from scratch. Figures 1 and 2 demonstrate that legal factors are certainly present in state constitutional arguments on remand, but most are utilized as an attempt to shore up the state court’s initial supportive federal decision. The clearest evidence for this claim is the fact that virtually all of this same legal evidence was available on initial appeal, and yet twenty-four of the thirty arguments pressing state claims on remand were not mentioned in the initial appeal. Remand briefs are responding not to changes in state legal factors but to changes in federal law, and it is the policy underlying these changes that received significant attention.

While remand arguments almost always engaged in some of the legal arguments we might traditionally expect lawyers to make, nine remand claimants (30 percent) attacked the Supreme Court as being reckless in its actions. Some were relatively gentle and complained of how SCOTUS’s decision was a “radically changed approach” or that its decisions were “curiously inconsistent.”[28] Other claimants were more dramatic in their attacks. In a search and seizure case, the claimant argued that recent federal decisions were “eviscerating the Fourth Amendment’s protection, culminating in last term’s two rulings leaving only tattered remains of the federal exclusionary rule.”[29] A claimant in another search and seizure case stressed the progressive diminution of rights at the federal level and wondered, given the major federal retrenchment, “what liberty interest and privacy rights have survived under the Fourth Amendment. It is thus left to [the Ohio Supreme Court] to determine whether any meaningful protections for Ohio citizens shall remain.”[30] The single strongest attack on the Supreme Court came in a speech case from New York:

Over the past decades the Supreme Court of the United States has slowly retreated from the expanded frontiers of liberty so painstakingly established by the “Warren” Court. The Supreme Court has radically revised traditional notions about the meaning and purpose of our Bill of Rights. Widespread inhibition of human rights resulting from a systematic repression of individual liberty has been seen by many of our high state courts as alarming and intolerable. Consequently, today state courts across the country are construing their own constitutions as providing broader individual protections than once afforded by their federal counterparts.[31]

Such claims add little to the weight of a legal argument and seem intended to undermine the natural deference toward SCOTUS in matters of constitutional law. If SCOTUS is acting in a reckless and dismissive manner, deference is undeserved and may actually be dangerous to the state’s citizens. State courts have a duty to aggressively defend their citizens against these irrational actions through their state constitutions. While these kinds of overt attacks on SCOTUS’s legitimacy are not the norm, nearly every remand argument attacked the policy behind the changes in federal law. These policy attacks form the most consistent argument in remand cases.

Policy arguments drew heavily on the logic of the US Supreme Court dissenters with secondary reliance on criticism from law reviews and other state courts. The most extreme example of this policy dominance came in Commonwealth v. Sheppard (1985), involving the good-faith exception to the exclusionary rule. The claimant argued that Mapp v. Ohio (1961) required exclusion of evidence to deter unconstitutional governmental behavior and, relying heavily on Justice Brennan’s dissent from recognizing the good-faith exception (United States v. Leon 1984), that such deterrence is required for any abuse of constitutional rights regardless of whether the error was made by the courts or the police. The concern of search and seizure is the protection of the individual’s rights and as well as the integrity of the judiciary itself even though “a majority of the current Supreme Court has abandoned the concept of judicial integrity.”[32] Brennan’s dissenting opinions crop up in a number of other cases, such as People ex rel. Arcara v. Cloud Books (1986), where the claimant quoted his dissenting opinion extensively to demonstrate how the SCOTUS doctrine was a “progressive denuding of First Amendment Rights” and how “sexually explicit but non-obscene [speech] has lost all but the surface veneer of its First Amendment Protection.”[33] Other dissenting justices received similar attention. On remand in Pap’s A.M. v. City of Erie (2002), the claimant stressed an earlier dissent from Justice White and stated that “Justice Stevens’ dissent [in the SCOTUS reversal] is also extremely well reasoned and appropriately critical of the Supreme Court’s plurality opinion” to demonstrate how the Supreme Court’s fractured rulings on regulation of nude dancing establishments were flawed and unpersuasive.[34] A claimant in a right to counsel case from Texas similarly utilized Justice Breyer’s dissenting opinion from the reversal to show how the Supreme Court’s new decision, which the brief described as a “rejection of national consensus of court authority” on the Sixth Amendment, “would emasculate the protections of the guarantee of a ‘right to counsel.’”[35]

Two search cases complained of trends in federal search law, but in opposite directions. In one case, the claimant complained that SCOTUS decisions were based on “legal fictions” as opposed to the actual facts of the case “so as to better enable it to draw ‘bright lines.’”[36] Another claimant, however, complained that the Supreme Court’s flexible totality of the circumstances test simply reinforced abusive practices, that the state court should adopt bright-line tests to correct the disparity of power between police and citizens, and that such a bright-line rule is easier for the police to comply with anyway.[37] In a case on standing to challenge searches, another claimant argued that the state court’s original decision would lead to better policing because it would hold police accountable for all illegal searches where SCOTUS had adopted a rule limiting the right to challenge a search to those with a reasonable expectation of privacy, a subjective standard.[38]

Finally, claimants invoked consequentialist arguments about the negative effects of SCOTUS’s doctrinal shift. For example, a Florida claimant in Haliburton v. State (1987)[39] discussed the structural difference in Florida that gave broad latitude to prosecutors and how the federal rule on when counsel attached would permit prosecutors to time the filing of charges to avoid the presence of counsel during the criminal investigation. After SCOTUS held that statements made to a probation officer were not subject to Miranda warnings, a claimant stressed the danger of this rule, noting that “defense attorneys in Minnesota will understandably tell their probationer clients that whenever they even remotely suspect that information requested by their probation officers may be incriminating they should no longer discuss such information with the probation officer and demand to see their attorney at once.”[40] This unfortunate outcome of SCOTUS’s decision would undermine the purpose of probation and complicate the duties of probation officers more than necessary, something the state court could easily correct. Thus the warning was that state courts had a duty to correct the negative policy effects of the changing federal doctrine.

Do Courts Respond?

While this chapter is focused on exploring how lawyers argue cases, some attention to outcomes is reasonable. After all, if state courts never accept a state argument on remand, lawyers would be less inclined to offer such claims. Any implication drawn from outcomes is limited, however, by the fact that many variables influence judicial decisions. Of the thirty cases where the claimant asserted a state claim on remand, fourteen (47 percent) were accepted by the state supreme court. In two other cases, the claimant won on alternative grounds. For the purposes of this study, I treat any decision that did not accept a state claim as a rejection even if it was not fully considered by the court.

Perhaps surprisingly, there was little concern with the failure to raise or preserve a state constitutional claim. The Michigan Supreme Court did express skepticism for the fact that the claimant “did not raise any state constitutional claims until he was before” SCOTUS, implying that it was a transparent attempt to avoid federal jurisdiction (People v. Long 1984, 197n4). Most state supreme court rejections expressed a preference for interpreting the state provision in lockstep with the federal provision, meaning that state law was identical to the federal doctrine. The Illinois Supreme Court engaged in an extended analysis of its history of refusing to interpret state constitutional rights independently, concluding that “we reaffirm our commitment to limited lockstep analysis not only because we feel constrained to do so by the doctrine of stare decisis, but because the limited lockstep approach continues to reflect our understanding of the intent of the framers of the Illinois Constitution of 1970. This court’s jurisprudence of state constitutional law cannot be predicated on trends in legal scholarship, the actions of our sister states, a desire to bring about a change in the law, or a sense of deference to the nation’s highest court” (People v. Caballes 2006, 44–45). The Minnesota Supreme Court similarly declared that its initial decision was based on the implicit assumption that the federal and state provisions were coextensive, and it saw no reason to alter that decision on remand even though it had specifically ordered briefing on the state constitution (State v. Carter 1999). The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals not only rejected the state argument but criticized the claimant for invoking federal dissenters: “Appellant must do more than merely argue that the Supreme Court majority ‘got it wrong,’ the dissent ‘got it right,’ and therefore, Texas courts should follow the dissent rather than the Supreme Court majority on this constitutional issue” (Cobb v. State 2002, 267).

In nearly half of the cases, the state court accepted the state claim and at times appeared to embrace an argument for avoiding federal retrenchment. In siding with George Upton, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court held that the federal totality of the circumstances test “lack[ed] the precision that we believe can and should be articulated in stating a test for determining probable cause” (Commonwealth v. Upton 1985, 556). The Florida Supreme Court directly rejected the policy of a recent SCOTUS decision with primary reliance on Justice John Paul Stevens’s dissent in that decision (Haliburton v. State 1987, 1090). Twice the Washington Supreme Court offered a limiting interpretation of the intervening SCOTUS decision but then turned to state law as firmer ground for the decision. In one case involving a recent SCOTUS change in free exercise of religion doctrine, the Washington court admitted it could distinguish this decision but that it would “eschew the ‘uncertainty’ of [SCOTUS’s decision] and rest our decision also on independent” state grounds (First Covenant Church v. City of Seattle 1992, 223). Similarly, in a case involving recent death penalty jurisprudence, the Washington court responded to its own dissenting justice that if the majority happened to misunderstand federal doctrine, the same result was required under state law (State v. Bartholomew 1984).

This finding suggests that state courts are open, some of the time, to direct avoidance of recent SCOTUS decisions. That occasionally, the policy arguments work. Of course, this is not to argue that state constitutional decisions lack legal legitimacy. Policy-based arguments have always been an element of legal decision-making. Nor do I mean to imply that these decisions rely exclusively on such grounds. For example, the Washington and Minnesota decisions rejecting federal retrenchment in free exercise engaged in an analysis of text, history, and prior judicial experience in addition to any policy objections.

Conclusion

The findings here fit with the expectations. Lawyers rarely offer state constitutional arguments without some strong signal—the strongest signal being the rejection of a federal rights argument by SCOTUS. As this forecloses the area completely, or nearly so, claimants have little choice but to either abandon the issue or turn to state constitutions as a second-best alternative. And that is how lawyers treat state constitutions, as second best. Lawyers on remand discover a state alternative that tends to focus as much or more on the policy critiques of SCOTUS as state legal sources.

This has two broader implications, first for the study of strategies after courtroom defeats. Too often, scholars treat a definitive SCOTUS decision as the end of a dispute. Social movements have found ways to turn courtroom losses into benefits in a variety of ways. Regular claimants, however, have less use for such benefits, and understanding how they react to losses expands our knowledge of strategic legal action after losses. Naturally, scholars focus on the level of decision-making that has the broadest potential policy impact. As federal constitutional law applies nationally, the focus tends to be there. Claimants, however, have a number of legal options available to them, and as this study shows those claims are often viable means of achieving victory. The policy impact will obviously be more limited (to within a single state), but the claimant still wins her narrow goal whether it be reversing an administrative decision, invalidating a state statute, or reversing a criminal conviction. This suggests the value of better understanding the full range of legal claims that a litigant develops to evaluate the broader context of litigation. These strategies may include constitutional ones—whether federal or state—but also statutory, administrative, or even common-law alternatives.

The second implication is for the study of state constitutional law. Studies have long found that state constitutional rights law is underdeveloped. State courts infrequently rely on state rights provisions, preferring to rely on federal doctrine. One criticism of state constitutionalism is that it is reactive not to state legal concerns but ideological differences with changing federal doctrine. The findings here may modify that criticism in part because courts respond to the arguments presented to them. If lawyers primarily offer state constitutional claims where federal law retrenches, then state courts may be less to blame than the critics suggest. Of course, the failure to raise, brief, and argue state constitutional claims also extended the legal process unnecessarily. In nearly half of the cases studied here, the claimant eventually won on a state claim but only after a SCOTUS appeal that added time and costs to the claimant involved.

References

Aguilar v. Texas, 378 U.S. 108 (1964). (↵ Return)

Albiston, Catherine. 1999. “The Rule of Law and the Litigation Process: The Paradox of Losing by Winning.” Law & Society Review 33: 869–910. (↵ Return)

Barnes v. Glen Theater, 501 U.S. 560 (1991). (↵ Return)

Beavers, Staci L., and Craig F. Emmert. 2000. “Explaining State High-Courts’ Selective Use of State Constitutions.” Publius 30: 1–15. (↵ Return)

Bickel, Alexander M. 1962. The Least Dangerous Branch: The Supreme Court at the Bar of Politics. Indianapolis, IN: Bobbs-Merrill Company. (↵ Return)

Brennan, William J. 1977. “State Constitutions and the Protection of Individual Rights.” Harvard Law Review 90: 489–504. (↵ Return)

Cauthen, James N.G. 2000. “Expanding Rights under State Constitutions: A Quantitative Appraisal.” Albany Law Review 63: 1183–202. (↵ Return)

Cobb v. State, 85 S.W.3d 258 (Tex. Crim. 2002). (↵ Return)

Commonwealth v. Upton, 458 N.E.2d 717 (Mass. 1983). (↵ Return)

Commonwealth v. Upton, 476 N.E.2d 548 (Mass. 1985). (↵ Return)

Cushman, Barry. 1998. Rethinking the New Deal Court: The Structure of a Constitutional Revolution. New York: Oxford University Press. (↵ Return)

Depoorter, Ben. 2013. “The Upside of Losing.” Columbia Law Review 113: 817–62. (↵ Return)

Emmert, Craig F., and Carol Ann Traut. 1992. “State Supreme Courts, State Constitutions, and Judicial Policymaking.” Justice System Journal 16: 37–48. (↵ Return)

Employment Division v. Smith, 494 U.S. 872 (1990). (↵ Return)

Epp, Charles R. 1998. The Rights Revolution: Lawyers, Activists, and Supreme Courts in Comparative Perspective. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (↵ Return)

Epstein, Lee, and Jack Knight. 1998. The Choices Justices Make. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Quarterly Press. (↵ Return)

Esler, Michael. 1994. “State Supreme Court Commitment to State Law.” Judicature 78: 25–32. (↵ Return)

Farole, Donald J. 1998. Interest Groups and Judicial Federalism: Organizational Litigation in State Judiciaries. Westport, Conn.: Praeger. (↵ Return)

Fino, Susan P. 1987. “Judicial Federalism and Equality Guarantees in State Supreme Courts.” Publius 17: 51–67. (↵ Return)

First Covenant Church v. City of Seattle, 120 Wash.2d 203 (1992). (↵ Return)

Friedman, Lawrence. 2011. “Path Dependence and the External Constraints on Independent Constitutionalism.” Penn State Law Review 115: 783–836. (↵ Return)

Friesen, Jennifer. 2006. State Constitutional Law: Litigating Individual Rights, Claims and Defenses. 2 vols. Newark, NJ: LexisNexis. (↵ Return)

Galanter, Marc. 1974. “Why the ‘Haves’ Come out Ahead: Speculations on the Limits of Legal Change.” Law & Society Review 9: 95–160. (↵ Return)

Graber, Mark A. 2006. “Legal, Strategic, or Legal Strategy: Deciding to Decide During the Civil War and Reconstruction.” In The Supreme Court and American Political Development, eds. Ronald Kahn and Ken I Kersch. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. 33–66. (↵ Return)

Haliburton v. State, 514 So.2d 1088 (Fla. 1987). (↵ Return)

Hathaway, Oona A. 2001. “Path Dependence in the Law: The Course and Pattern of Legal Change in a Common Law System.” Iowa Law Review 86: 601–65. (↵ Return)

Hollis-Brusky, Amanda. 2015. Ideas with Consequences: The Federalist Society and the Conservative Counterrevolution. New York: Oxford University Press. (↵ Return)

Illinois v. Gates, 462 U.S. 213 (1983). (↵ Return)

Jensen v. Quaring, 472 U.S. 478 (1985). (↵ Return)

Keck, Thomas M. 2004. The Most Activist Supreme Court in History: The Road to Modern Judicial Conservatism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (↵ Return)

Kelo v. New London, 545 U.S. 469 (2005). (↵ Return)

Krehbiel, Keith. 1998. Pivotal Politics: A Theory of U.S. Lawmaking. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (↵ Return)

Latzer, Barry. 1991. State Constitutions and Criminal Justice. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. (↵ Return)

Lemon v. Kurtzman, 403 U.S. 602 (1971). (↵ Return)

Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U.S. 643 (1961). (↵ Return)

Massachusetts v. Upton, 466 U.S. 727 (1984). (↵ Return)

Michigan v. Long, 463 U.S. 1032 (1983). (↵ Return)

Neder v. United States, 527 U.S. 1 (1999). (↵ Return)

NeJaime, Douglas. 2011. “Winning through Losing.” Iowa Law Review 96: 941–1012. (↵ Return)

Pap’s A.M. v. City of Erie, 719 A.2d 273 (Pa. 1998). (↵ Return)

People v. Caballes, 851 N.E.2d 26 (Ill. 2006). (↵ Return)

People v. Long, 359 N.W.2d 194 (Mich. 1984). (↵ Return)

Pickerill, J. Mitchell. 2004. Constitutional Deliberation in Congress: The Impact of Judicial Review in a Separated System. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. (↵ Return)

Price, Richard S. 2013. “Arguing Gunwall: The Effect of the Criteria Test on Constitutional Rights Claims.” Journal of Law and Courts 1: 331–61. (↵ Return)

———. 2015. “Lawyers Need Law: Judicial Federalism, State Courts, and Lawyers in Search and Seizure Cases.” Albany Law Review 78: 1393–458. (↵ Return)

———. 2017. “Linde’s Legacy: The Triumph of Oregon Constitutional Law, 1970–2000.” Albany Law Review 80: 1541–602. (↵ Return)

Price, Richard S., and Thomas M. Keck. 2015. “Movement Litigation and Unilateral Disarmament: Abortion and the Right to Die.” Law & Social Inquiry 40: 880–907. (↵ Return)

R.A.V. v. City of St. Paul, 505 U.S. 377 (1992). (↵ Return)

Schmidt, Christopher W. 2015. “Litigating against the Civil Rights Movement.” University of Colorado Law Review 86: 1174–220. (↵ Return)

Segal, Jeffrey A., and Harold J. Spaeth. 2002. The Supreme Court and the Attitudinal Model Revisited. New York: Cambridge University Press. (↵ Return)

Somin, Ilya. 2015. The Grasping Hand: Kelo v. New London & the Limits of Eminent Domain. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (↵ Return)

Spinelli v. U.S., 393 U.S. 410 (1969). (↵ Return)

State v. Bartholomew, 101 Wash.2d 631 (1984). (↵ Return)

State v. Carter, 596 N.W.2d 654 (Minn. 1999). (↵ Return)

State v. Gunwall, 106 Wash.2d 54 (1986). (↵ Return)

State v. Hershberger, 444 N.W.2d 282 (Minn. 1989). (↵ Return)

State v. Recuenco, 154 Wash.2d 156 (2005). (↵ Return)

Sutton, Jeffrey S. 2009. “Why Teach—and Why Study—State Constitutional Law.” Oklahoma City University Law Review 34: 165. (↵ Return)

Tarr, G. Alan. 1998. Understanding State Constitutions. Princeton: Princeton University Press. (↵ Return)

Tarr, G. Alan, and Mary Cornelia Porter. 1988. State Supreme Courts in State and Nation. New Haven: Yale University Press. (↵ Return)

United States v. Leon, 468 U.S. 897 (1984). (↵ Return)

United States v. Place, 462 U.S. 696 (1983). (↵ Return)

———. 1991. “State Constitutional Law: Teaching and Scholarship.” Journal of Legal Education 41: 243–49. (↵ Return)

———. 2009. The Law of American State Constitutions. New York: Oxford University Press. (↵ Return)

Wisconsin v. Mitchell, 508 U.S. 476 (1993). (↵ Return)

Witters v. State, Commission for the Blind, 102 Wash.2d 624 (1984). (↵ Return)

Class Activity

Examine your state constitutional bill of rights. What provisions are most surprising to you? How does it differ from the federal Bill of Rights? What makes those differences meaningful?

Many first-generation constitutions in the 1780s and 1790s have provisions like this one from Vermont (Ch. I Art. 13): “That the people have a right to freedom of speech, and of writing and publishing their sentiments, concerning the transactions of government, and therefore the freedom of the press ought not to be restrained.” Why do you think it uses ought instead of shall as in the First Amendment?

- To be fair, this is a pessimistic reading of Brennan’s argument. He presents his case as a faithful adherence to the principle of federalism, but as Earl Maltz (1988) argues, this seems difficult to square with Brennan’s history (but see Williams 1998). For a more principled and nuanced defense of judicial federalism, see Linde (1970). ↵

- I draw the following basic case facts from this decision. ↵

- The article states, Every subject has a right to be secure from all unreasonable searches, and seizures, of his person, his houses, his papers, and all his possessions. All warrants, therefore, are contrary to this right, if the cause or foundation of them be not previously supported by oath or affirmation; and if the order in the warrant to a civil officer, to make search in suspected places, or to arrest one or more suspected persons, or to seize their property, be not accompanied with a special designation of the persons or objects of search, arrest, or seizure: and no warrant ought to be issued but in cases, and with the formalities prescribed by the laws. [There are no pages, it is a constitutional provision. It is equivalent to citing the First Amendment ↵

- Commonwealth v. Upton, 458 N.E.2d 717, defendant’s supplemental brief at 25. ↵

- Upton, defendant’s supplemental brief at 32, 34–35. ↵

- Commonwealth v. Upton, 476 N.E.2d 548 (Mass. 1985), defendant’s brief on remand at 1. The second decision was United States v. Leon (1984), establishing the good-faith exception to the exclusionary rule. ↵

- Upton, 476 N.E.2d 548, defendant’s brief on remand at 15. ↵

- State supreme court is used as a generic term for the highest appellate court even if that court uses a different title, such as the New York Court of Appeals. ↵

- Pap’s A.M. v. City of Erie, 719 A.2d 273 (Pa. 1998), appellant’s initial brief at 21–23. ↵

- Pap’s A.M., appellant’s initial brief at 23. ↵

- State v. Hershberger, 444 N.W.2d 282 (Minn. 1989), appellant’s initial brief at 41. ↵

- People v. Conyers, 49 N.Y.2d 174 (1980), defendant-respondent’s initial brief. ↵

- Witters v. State, Commission for the Blind, 102 Wash.2d 624 (1984), petitioner’s initial brief. ↵

- Witters is an unusual case in that the issue revolved around competing constitutional limitations with the claimant asserting a free-exercise argument and the state using the establishment clause to combat the issue. Because SCOTUS only dealt with the later claim, I used the state’s establishment claim for this study, as the state was arguing for a broader constitutional rule. ↵

- Washington Constitution, Art. I, Sec. 11 reads in part, “Absolute freedom of conscience in all matters of religious sentiment, belief and worship, shall be guaranteed to every individual, and no one shall be molested or disturbed in person or property on account of religion. . . . No public money or property shall be appropriated for or applied to any religious worship, exercise or instruction, or the support of any religious establishment.”{~?~AQ: Page(s)?}As with earlier, constitutional provisions have no page numbers. ↵

- State Higher Educ. Assistance Auth. v. Graham, 84 Wash.2d 813 (1974); Weiss v. Bruno, 82 Wash.2d 199 (1973). ↵

- State v. Wyant, 624 N.E.2d 722 (Ohio 1994), appellant’s brief on remand at 9–17. ↵

- Desimone v. State, 996 P.2d 405 (Nev. 2000), appellant’s supplemental points and authorities at 1 (“Nothing in United States v. Ursery compels this court to reverse its decision . . . and the judgment previously entered by this court should be reinstated.”) ↵

- Fensterer v. State, 509 A.2d 1106 (Del. 1986), defendant below-appellant’s brief on remand. ↵

- Commonwealth v. Hicks, 596 S.E.2d 74 (Va. 2004), appellee’s brief on remand; Elliot v. Commonwealth, 593 S.E.2d 263 (Va. 2004), declaring that the state constitution provided no greater protection for speech. ↵

- Witters v. State, Commission for the Blind, 112 Wash.2d 363 (1989), respondent’s brief on remand at 25. ↵

- Haliburton v. State, 514 So.2d 1088 (Fla. 1987), supplemental brief of appellant on remand at 8. ↵

- State v. Mitchell, 504 N.W.2d 610 (Wis. 1993), defendant-appellant’s memorandum of law on remand at 9–11. ↵

- Wyant, appellant’s brief on remand at 8; State v. Robinette, 685 N.E.2d 762 (Ohio 1997), appellee’s brief on remand at 10; American Association of University Professors, Central State University Chapter v. Central State University, 717 N.E.2d 286 (Ohio 1999), appellee / cross appellant’s brief on remand at 13–14. The opinion cited was Arnold v. City of Cleveland, 67 Ohio St.3d 35 (1993). ↵

- Immuno AG v. Moor-Jankowski, 77 N.Y.2d 235 (1991), defendant-respondent’s brief on remand at 45–46, 47–48 (citing Arcara v. Cloud Books, Inc., 503 N.E.2d 492 [N.Y. 1986] and O’Neill v. Oakgrove Construction, Inc., 523 N.E.2d 277 [N.Y. 1988]). ↵

- Van Arsdall v. State, 524 A.2d 3 (Del. 1987), defendant-appellant’s brief on remand. ↵

- People v. Caballes, 851 N.E.2d 26 (Ill. 2006), defendant-appellant’s brief on remand; State v. Recuenco, 163 Wash.2d 428 (2008), petitioner’s brief on remand; Witters, respondent’s brief on remand. Part of the reason for more complex arguments may also be the fact that two of these cases were influenced by the Washington Supreme Court’s strong adherence to a specific approach to state constitutional law (Price 2013). ↵

- State v. Carter, 596 N.W.2d 654 (Minn. 1999), appellant’s brief on remand at 6; People v. Belton, 55 N.Y.2d 49 (1982), appellant’s brief on remand at 5. ↵

- Commonwealth v. Sheppard, 476 N.E.2d 541 (Mass. 1985), appellant’s brief on remand at 16. ↵

- Robinette, appellee’s brief on remand at 19. ↵

- People v. Ferber, 57 N.Y.2d 256 (1982), appellant’s brief on remand at 6. ↵

- Sheppard, defendant’s brief on remand at 22. ↵

- People ex rel. Arcara v. Cloud Books, 68 N.Y.2d 296 (1986), appellant’s brief on remand at 23, 24. ↵

- Pap’s A.M. v. City of Erie, 812 A.2d 591 (Pa. 2002), appellant’s brief on remand at 16. ↵

- Cobb v. State, 85 S.W.2d 258 (Tex. Crim. App. 2002), appellant’s brief on remand at 10, 11. ↵

- People v. Long, 359 N.W.2d 194 (Mich. 1984), defendant’s brief on remand at 23. ↵

- Robinette, appellee’s brief on remand at 14–29. ↵

- Carter, appellant’s brief on remand. ↵

- Haliburton, supplemental brief of appellant on remand at 8. ↵

- State v. Murphy, 380 N.W.2d 766 (Minn. 1986), appellant’s brief on remand at 30–31. ↵