Policy Making

33 Issue Emergence and Evolution in the US Supreme Court

Richard L. Pacelle Jr. and Barry W. Pyle

The construction of judicial doctrine by the US Supreme Court has been compared to piecing together a giant mosaic. Public policy is normally associated with the landmark Court decisions, ignoring the processes that led to such important decisions and the work necessary to flesh out the remaining questions left in the wake of the major pronouncement. Supreme Court decisions, no matter how significant, raise more questions than they answer. Landmark decisions like Brown v. Board of Education, Roe v. Wade, and Miranda v. Arizona did not emerge fully developed, nor were they the last words in their areas of law. In fact, each preceded an explosion of litigation and Court attention in the areas of school desegregation, reproductive rights, and self-incrimination, respectively. Thus it is useful to view judicial doctrine construction as continually evolving through a series of decisions and a number of stages.

Although it is often portrayed as above politics and subject only to the rule of the law, the Supreme Court is an active participant in making public policy. Policy unfolds through the construction of legal doctrine over time. Justices make decisions in individual cases, and those decisions contribute to the construction of policy. Each time the Supreme Court decides a case, that decision becomes part of an evolving precedent that is binding in similar cases. This is a study of the emergence and development of policies in the Supreme Court. We argue that Supreme Court policy emerges and evolves in predictable ways. We consider the initiation and development of judicial policy and doctrine through a framework of policy evolution. This model of issue evolution is concerned with the origin of new issues, how they develop over time, the impact of the environment on these issues, and how issues are related to each other. The process of doctrinal construction involves the emergence of a new issue, which is often the result of activity in a related issue area; periods of stability; increased issue complexity; the spawning of other new issues; and occasionally, a retreat to a previous stage of development (Pacelle 2009; Richards & Kritzer 2002; Bartels & O’Geen 2015).

We believe that long-term policy making by the US Supreme Court follows a four-stage process in which purposive major actors (the justices and lower courts as well as interest groups and individual litigants) interact to address new issues, announce policy, apply policy in subsequent cases, and deal with possible policy conflicts with other issue areas.

Justices construct public policy through the precedents that come from individual decisions. Those decisions are pieced together into doctrine. Doctrine results from the ongoing conversation that happens among litigants, courts, and interest groups that defines the terms of debate about the constitutionality or legality of an issue. It is important to understand the roots of doctrine. The basis for new cases will affect how that issue area will unfold. It also helps explain why precedents seldom get overturned.

The Judicial Process: Building Doctrine and Making Policy

The Supreme Court makes policy through the process of legal interpretation. Issues of public policy are brought to the judiciary in the form of legal questions posed in the various cases. These questions require some combination of the interpretation of legislation, administrative regulations, past judicial precedents, and provisions of the Constitution. In selecting cases for review, deciding the scope of that review, and making the ultimate decisions on the merits, the Court makes important policy choices and allocates valuable resources (Baum 1997, 2006, 2017).

The Supreme Court is the one national governmental institution that often justifies its decisions and policy choices in writing. The opinion of the Court explains the policy position and provides an extensive justification for the decision. The decision will also be nested within the context of a series of precedents from similar cases. The need to justify decisions provides the justices with the opportunity to continue the construction of an evolving doctrine (Hansford & Spriggs 2006).

However, the judicial system is also passive. Judges cannot just wake up one morning and decide to make a pronouncement on an issue of interest. Rather, they have to wait for an appropriate case to come to the court’s docket. Litigants using the courts resemble (and are often part of) interest groups, but they approach the courts rather than (or in addition to) using the elected branches. Litigants use the Supreme Court for a variety of reasons. They may lack the power and resources to go to the elected branches of government. Strategically, the Court may be more sympathetic to the positions they advocate. Some issues, like criminal procedure and the rights of minorities, are more appropriate for the courts than the elected branches. And finally, groups use the courts to protect the gains they made elsewhere in the political structure (Epp 1998; Pacelle 2015).

When a case reaches the Supreme Court, justices rely primarily on four sources of information to help them in rendering decisions and constructing doctrine. First, the justices examine the briefs of the parties; the conflict that gives rise to the particular case involves the two parties to the litigation. Each of those litigants attempts to persuade a majority to issue a favorable decision through its briefs. Second, the justices obtain information regarding the litigants’ desired applications of law during oral arguments and can question the attorneys for clarification (Johnson 2004). Third, “repeat players,” often in the form of the litigation arms of interest groups, can expand the issue and the conflict beyond the two parties. These groups provide the Court with their own interpretations of the correct application of the law by filing amicus curiae briefs (Collins 2008). Finally, the justices obtain information to assist them in adjudicating the dispute from the opinions of the lower-court judges who initially disposed of the case (Corley, Collins, & Calvin 2011).

The goal for litigants in a particular case is to win. That is probably not a major revelation, but how and why they win have long-term implications. Remember that the majority opinion in a Supreme Court case is a precedent that sets policy. The ability to win numerous cases translates to the opportunity to shape doctrinal development, to insulate favorable precedents, and to bend the law to the litigant’s goals.

On the other side of the table are the justices. Presidents nominate justices who they hope will enact their legal and policy goals. Supreme Court behavior can be described as a policy-making process that is influenced by the justices’ individual preferences expressed as legal doctrine and tests. Purposive justices with similar policy preferences form coalitions around these standards to make policy in a given area and, given the opportunity, import the precedent to other issue areas (Bailey & Maltzman 2011).

Although they hope to see their policy views memorialized in doctrine, justices cannot disregard the law and precedent. Thus they adhere to what Gerhardt (2008) calls the “Golden Rule of Precedent”: justices need to respect other precedents so that when their views prevail and become precedent, other justices will respect their decisions. In other words, justices treat others’ precedents as they would like their own to be treated. Similarly, justices must protect the legitimacy of the institution (Clark 2011). Reckless disregard for the Court’s institutional authority can undermine the platform for individual policy goals. If justices are able to attain their policy goals but the Court has no respect from the other branches or the public, then those goals are less viable or may be threatened.

Thus justices work with like-minded litigants and signal them through their acceptance of petitions and decisions in similar cases (Baum 2006). As this process proceeds over time and through successive cases, these legal standards take on substantive meaning and create expectations that inform and influence the preferences of future justices, lower-court judges, litigants, and other participants as they accept, reject, or adapt legal standards in future cases.

Lower courts also play a significant role. The influence of courts of appeals flows up and down the judicial hierarchy. When legal issues are new or when existing rules are incomplete, courts of appeals help with filling gaps or providing a foundation. Thus it is not unusual to find circuit court judges engaged in the process of shaping or creating new legal rules (Hettinger & Lindquist 2012). Once the Supreme Court makes a decision, lower courts have to apply new precedent as it heads back down the ladder. Within the legal system, the opinions are precedents that constrain lower-court judges (vertical precedent) as well as their current colleagues and future justices (horizontal precedent; Corley, Collins, & Calvin 2011; Hettinger, Lindquist, & Martinek 2006). Moreover, majority opinions are guides for litigants, shaping the arguments they make in subsequent written briefs and during oral arguments (Epstein & Knight 1998).

Institutional rules and norms ask the justices to adhere to precedent and make consistent decisions to guide lower courts, governmental agencies, groups, and individuals. The types of questions as well as the responses of the litigants and justices change over time as the stages unfold. This model of issue evolution reveals how issues unfold, take root, and change over time. It also helps us understand how one issue can help create or sustain another issue.

The stages of the process speak to the opportunities and constraints that justices, litigants, and lower-court judges encounter and how they shift over time. New issues require building a foundation. Once that foundation is in place and earns the support of a majority, the dynamics change. The early decisions structure the development of the policy issue. The new issue normally becomes nested within similar reinforcing precedents. Litigants test the limits and seek to push the frontiers a little farther (or limit the reach if they oppose the Court’s position). The focus of litigants, lower-court judges, and justices may shift to related areas. There is a deliberate attempt to transplant the favorable precedents to those proximate issues. This is a major reason that the Court seldom overturns precedents. The construction of the individual precedents and the policy and doctrine they create is a slow process, and dismantling similarly takes a long time.

The Rise of New Issues

It is rare for new issues to suddenly appear on the Court’s agenda. Instead, new issues represent potential policy-making opportunities or the opening of a policy window (Kingdon 1995). Because Court policy and doctrine are tied to precedents, new issues stand a greater chance of survival on the Court’s agenda if actors (litigants, judges, and justices) can tie them to existing precedent in other areas of law. As issues emerge, litigants and justices may look for similar issues to advance. For instance, once the Supreme Court used the Fourteenth Amendment to remove some of the barriers to inequality (i.e., Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka 1954), they looked to other issues that might protect civil rights. Freedom of speech and association from the First Amendment were useful vehicles to protect civil rights protests (i.e., Brown v. Louisiana 1966; Pacelle 2009; Wahlbeck 1997).

Decisions like Brown v. Board of Education (1954) struck important blows for racial equality. It took the Court a little while, but it extended its review to other cases involving discrimination. Using similar precedents, the Court developed and refined scrutiny tests under the equal protection doctrine of the Fourteenth Amendment to extend the logic of Brown and racial discrimination to issues of gender (i.e., Craig v. Boren 1976) and citizenship (i.e., Graham v. Richardson 1971) discrimination.

Organized litigation is a major component in the rise and coupling of new issues and the metamorphosis of existing issues. First, many groups are involved in a variety of issue areas. The solicitor general (Pacelle 2003, 2018), American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU; Walker 1990), National Association for the Advancement of Colored Persons (NAACP; Wasby 1995), and conservative groups like the Washington Legal Foundation (Teles 2008) litigate across a range of issues. These groups try to transplant arguments and provisions that have been successful elsewhere. Equality litigation is a classic example, as advocates for the rights of the handicapped and elderly used principles and strategies advanced by the NAACP in race litigation (Olson 1981). Thus it is not surprising that new issues have antecedents in existing policies. Interest groups urge the extension of past decisions or constitutional principles. Justices with specific policy designs may also be involved in paving the way for new issues. This process may accelerate the Court’s normal incremental pace of change. In addition, groups operate aggressively when the environment is propitious (the Court is sympathetic) and seek to transplant favorable doctrine. When the environment changes, groups react defensively, retreating to their core and “trimming their argumentative sails” (Kobylka 1995, 125).

Because of its roots in the doctrine of another area of law, the new issue may be viewed in the context of the original area and takes on the color of the older policy area. Once a new issue emerges on its own, it typically lays claim to agenda space for the foreseeable future (Pacelle 1991; Baird 2004). Perhaps more significantly, the breakthrough may lead to a surge of activity in related areas. When an institution decides to consider an issue, it may in effect “commit itself to a whole chain of rationally related issues” (Crenson 1971, 172). Policy entrepreneurs, flushed with success, rush to the next issue to take advantage of the momentum (Kingdon 1995; Baumgartner & Jones 1993). This occurs in Congress as well as the courts. The New Deal was a perfect example of the widespread range of solutions to various economic problems. Similarly, in the 1960s, Congress passed in succession the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and embarked on housing and employments bills to implement Lyndon B. Johnson’s “Great Society.”

After the Court moved to protect the rights of individuals to be safe and secure in their homes from unwarranted search and seizure (under the Fourth Amendment), litigants and justices moved quickly to expand Fifth Amendment rights (like protections from self-incrimination) and Sixth Amendment rights (like the right to counsel). Groups like the ACLU were involved in all these major cases, and the same justices who supported extending the Fourth Amendment also voted to expand the reach of the related amendments.

On the other hand, if proper conditions are not present, policy windows may not open, and new issues may not emerge. Justices may want issues to “percolate” in the lower courts before they turn their attention to them. For instance, the Court’s refusal for years to attend to gay and lesbian rights is an example of a window that was closed until recently. Petitioners sought entry through a variety of existing windows including criminal law, education, and public employment. Their claims invoked equal protection, privacy, due process, and the First Amendment (Zick 2018).

Policy Framework and Free Exercise of Religion

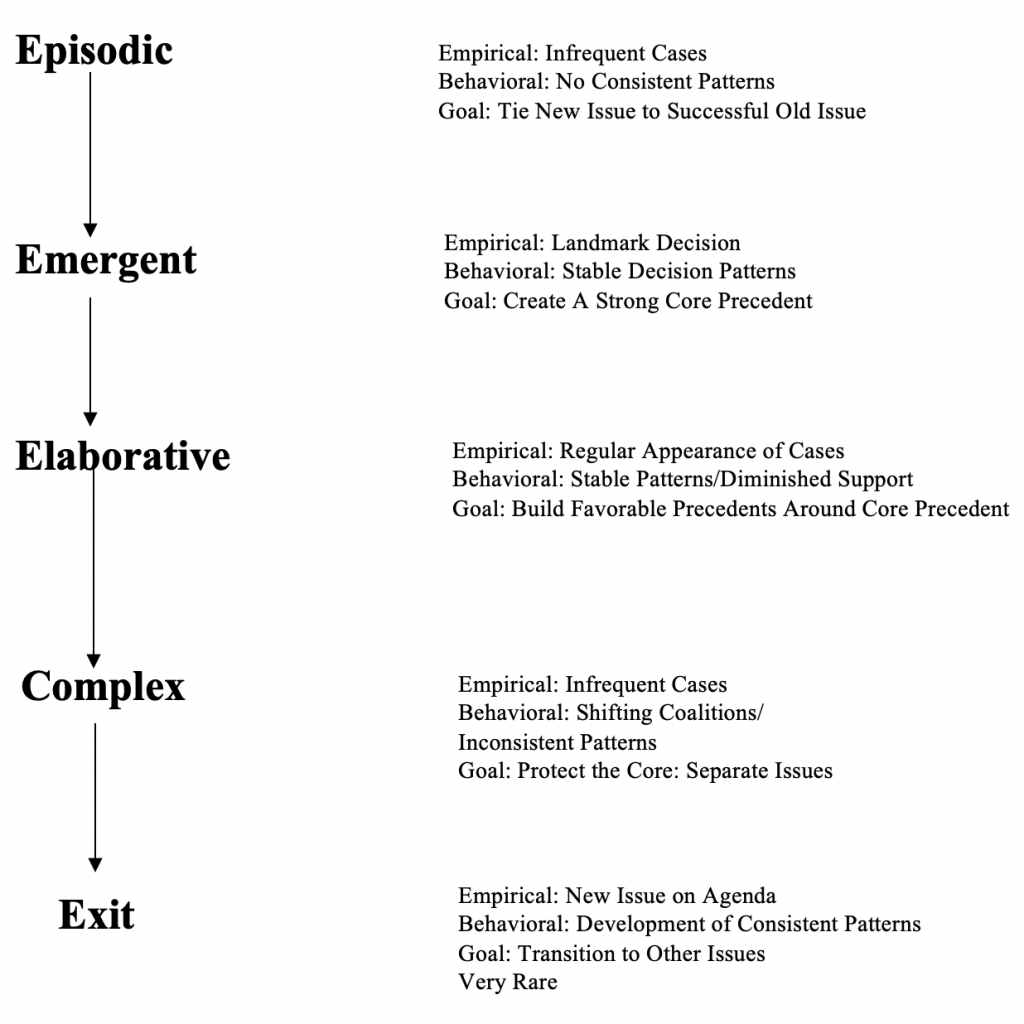

We conceive of policy initiation and evolution in the Supreme Court as having four distinct stages—episodic, emergent, elaborative, and complex. A fifth stage, exit, is achieved if the Court decides to leave an area altogether. For instance, the Court has reduced its attention to economic issues, and this largely leaves the determination of these issues to other actors, such as Congress (Pacelle 1991). This is a rare phenomenon. Figure 1 traces the typical pattern of policy development for issue areas once they emerge in their own right. Once the new issue is evaluated on its own terms, it begins to move through its own evolutionary cycle. Figure 1 also shows the different expectations for each stage of policy evolution. We use the example of the free exercise of religion doctrine to explain the model because it is a consequential part of the First Amendment; is broadly related to other rights, such as freedom of expression and association; and has an intertwined relationship with establishment of religion cases (like aid to religious schools and public displays of religious symbols).

The initial test or standard for free exercise litigation was the secular regulation rule. That standard was very deferential to the government. In other words, it made it relatively easy for the government (mostly state and local governments) to restrict religious practices. A broad change in the political environment caused in part by the Great Depression (a new party in control of the White House and Congress and eventually the Supreme Court) created the chance to revisit this rule. In an otherwise forgettable case (United States v. Carolene Products (1938)), Justice Harlan Fiske Stone filed his famous footnote four, arguing that civil liberties and the rights of insular minorities should be held in a “preferred position.” He maintained the Court should adopt a more rigorous standard of review that would not be deferential to the government. Quite to the contrary, this standard asked the government to meet a very high standard before it could restrict individual liberties. The policy window had been thrown open, and a number of groups tried to push their issues through it (Pacelle 1991).

Episodic

The first stage of policy evolution in the Supreme Court is the episodic stage. At this stage, a new issue arises, and the Court searches for some doctrinal home for that new issue. The Court typically finds a related area of law and transplants the precedent, providing a temporary home. The episodic phase is marked by infrequent appearance on the Court’s agenda and inconsistency in individual- and institutional-level decision-making. The new issue typically results from a related issue or as a conscious effort on behalf of litigants or justices seeking to transplant success from a different area. At this stage, the Court searches for some help in understanding how to decide the case and where it fits in generally. Litigants may suggest an existing, related doctrinal home for the new issue. The novel area may take a while to develop its own doctrinal identity. Because the issue does not arise annually or with any predictability, the nature of early doctrine at this stage is likely to be unstable.

As the search for a new standard continues, the episodic stage creates opportunities for interested actors to suggest the building blocks for new doctrine. As noted, there is, in effect, a “conversation” among litigants, courts, and interest groups that defines the terms of the debate about the constitutionality or legality of an issue. Litigants, particularly “repeat players” (Galanter 1974), provide the Court with a variety of possible constitutional doctrines and legal rationales as various decision-making alternatives (Collins 2012; Johnson 2004; Baird 2004; 2007). Lower courts also contribute to doctrinal development (Westerland, et al. 2010; Pacelle 2015). Finally, the justices themselves play the role of policy entrepreneurs and suggest doctrinal choices to their colleagues and lobby for their preferred standard through the opinion-writing process (Baum 2006; 2017).

The first major free exercise of religion case (of the twentieth century) to be decided by the Court was Cantwell v. Connecticut (1940). Newton Cantwell was proselytizing in a predominantly Catholic section of New Haven, Connecticut. He would stop people on the street and play them a record that was anti-Catholic. He was charged with breach of peace and soliciting without a license. The Court ruled that this violated Cantwell’s right to freedom of speech.

In Cantwell, the Court incorporated the free exercise provision of the First Amendment (Cortner 1981) but ultimately focused on the free speech aspects of the case. Thus decisions that upheld freedom of speech helped create a favorable environment for recognizing free exercise rights. The Cantwell case is part of the episodic stage of free exercise policy because the decision began to shape doctrine but did not clearly define the standards for later exercise cases. During the 1943–61 period, the Court decided very few free exercise cases that did not involve free expression. As a result, free exercise doctrine remained in the episodic stage for a generation (Zick 2018).

Free exercise policy evolved from freedom of expression, a related issue area, inheriting the basic structure from their common backgrounds. The connection between the early free exercise cases and free speech policy was not surprising. Given the proselytizing efforts of the religion, the free exercise questions raised by the Jehovah’s Witnesses were inexorably interwoven with free speech concerns (Peters 2000).

The litigation arm of the Jehovah’s Witnesses was the first group to establish a consistent presence in the area of free exercise. The Jehovah’s Witnesses suffered some defeats along the way, to be sure, but in areas like the flag salute cases, early losses were turned into monumental and symbolic victories. Indeed, the success of the Jehovah’s Witnesses served as an impetus for the civil rights movement and its litigation strategies, which in turn were the models for subsequent groups, showing how precedents and strategies get transplanted (Peters 2000). At some point as the issue evolved from expression to the so-called Sunday Closing Laws cases, the Jehovah’s Witnesses ceded the area, and the ACLU filled the leadership vacuum. The ACLU was able to help construct the Sherbert test, expand its reach, and try to protect from reversal (Walker 1990).

Emergent

The evolutionary development of free exercise doctrine was an organic extension of the more venerable free speech cases. As a relatively new issue, the presence of existing free speech precedents gave the Court a foundation on which to build free exercise doctrine. The cost, however, was that the development of religion policy was constrained by free speech standards. Developmental pathways shape the evolution of the new issue and constrain the variation. The doctrine woven of free speech and free exercise cases was not always clear, but it lasted decades (Zick 2018).

To achieve its own status, the new policy area must advance to the second phase, the emergent stage. The victorious actors (litigants, groups, and justices) from the episodic stage are encouraged to bring additional cases. But transplanting a precedent is not ideal or always a perfect fit, thus there is a need for litigants and justices to do some tailoring. During the emergent stage, the goal is to create the strongest possible precedent. Normally there is a time of experimentation as litigants and justices strive to create a test or standard that will survive.

Eventually, the justices understand that they need to isolate the new area and develop its own standards. And this leads to the emergent stage. The emergent stage is marked by a couple of elements. First, the issue makes a regular claim to agenda space. This signals the Court’s recognition that additional doctrinal work is necessary, and its intention is to address the issue systematically. The Court needs to “invest” or “commit” future resources (in the form of agenda space). Second, the Court finds the issue its own key landmark precedent (Pacelle 1991).

Substantively, emergent-stage cases are first-generation questions, the core concern of the developing policy area. The stage is marked by the cases immediately preceding, including, and following the central landmark. The landmark defines the core question, and the cases immediately following begin to define and shape the scope of the seminal decision and may limit or constrain the range of long-term deviation (Pacelle 1991; Baird 2007).

In the free exercise of religion cases, the Sunday Closing Law cases (1961) began to shape a new doctrine, and ultimately, Sherbert v. Verner (1963) provided the landmark case that defined the emergent stage. In its decisions involving Sunday Closing Laws, the Court refined and developed its test for free exercise. The Court distinguished between direct and indirect effects on religion. The new standard was less deferential than the Secular Regulation rule but still not overly protective of free exercise.

In Sherbert v. Verner, the Court fashioned a test to evaluate future free exercise cases. The Court ruled that South Carolina’s denial of social service benefits to a woman who was fired because of her refusal to work on her Sabbath was a denial of her free exercise of religion. The essence of Justice Brennan’s dissent in Braunfeld v. Brown (1961), one of the Sunday Closing Law cases, became the majority opinion in Sherbert. The new standard added an important component to the existing standard: the state must have a “compelling interest” to regulate the exercise of religion. In so doing, Brennan reestablished the close connections between free exercise and free speech (Morgan 1972). The decision had the effect of providing more protection for religious freedom (Eisler 1993). The Sherbert case thus marks the beginning of the transition from the emergent stage to the elaborative stage of issue evolution.

As the emergent stage closes, there is an expectation that the Court will come to evaluate these questions in a consistent manner. There is a standard or test now in place. Justices are policy makers with their own sincere preferences. As members of the Court of last resort, however, justices have an institutional obligation to decide cases in a consistent manner so as to guide lower courts. Thus justices’ policy goals are mediated or constrained by institutional rules and norms, and their notions of their judicial roles affect the evolution of policy.

The emergent stage should not be especially long in duration, but it may take a range of cases for the Court to flesh out the doctrine. It does, however, create the shock to the system that begins the process of dynamic growth. This is consistent with Sunstein’s notion of “width” (1999, 16–19). Sunstein argues that decisions have “width” if they set a clear standard, are applicable to other cases in the specific issue area, and are the governing principles for that area of law. The landmark structures litigation and decision-making for decades. The decisions that follow in subsequent cases are more fact intensive and thus narrower in applying the existing standard and are found in the elaborative stage.

Elaborative

Once the landmark decision sets the precedent and anchors it in a test or standard, the issue area moves to the elaborative stage. At some point, the Court should resolve first-generation questions in a manner that will guide lower courts. Having settled the core questions in the emergent stage, it is uncertain how much further the justices are willing to go: Will the Court continue to support rights and liberties? At the elaborative stage, the fact situations in later cases present the Court with increasingly more difficult issues. For example, in Mapp v. Ohio (1961), the police went into the house without a warrant. It was a relatively clear violation of Dollree Mapp’s Fourth Amendment rights. Later search and seizure cases were cast in confounding shades of gray. Is a warrant needed if the police are in hot pursuit of an armed suspect or want to enter a detached garage? In civil rights, Brown banned state-mandated segregation in schools. But how would the Court treat segregation that was accidental or just developed over time? Would the Court sanction affirmative action or “reverse discrimination” to remedy past discrimination?

In the elaborative stage, the justices, litigants, and lower courts begin the process of applying the test and doctrine to issues that come before the Court. Some of these actors try to push the boundaries of the doctrine and nest the landmark precedent in related policy areas. By spreading the range of the precedent out, they hope to create a web to protect the core landmark and make it harder to excise or reverse. Still other justices, litigants, and lower-court judges may seek opportunities to challenge the new doctrine and supplant it with one more closely aligned with their policy goals. Challenges to the new doctrine are aided by the fact that issues grow increasingly complex as the elaborative stage continues. Ultimately, support for the new policy should wane as the issues get more difficult and as justices who supported the emergent-stage doctrine leave the Court.

A number of freedom of religion cases involved employment issues. In some of these cases, an individual might be asked to work on his or her Sabbath. A failure to work might lead to this person’s dismissal. The individuals were often denied unemployment benefits. The Court had to rule whether the denial of benefits a violation of the free exercise of religion. These were elaborative cases, raising more difficult questions for the Court. The Court’s decisions in cases like Thomas v. Review Board (1981), Hobbie v. Unemployment Commission (1987), and Frazee v. Department of Employment (1989) applied the Sherbert test, ruling that these restrictions were violations of the individuals’ free exercise of religion.

The Court used Sherbert to uphold free exercise claims in Wisconsin v. Yoder (1972 involving the objections of the Amish to compulsory school attendance laws) and McDaniel v. Paty (1978; striking a Tennessee law that barred clergy from serving in public office). Overall, the Court’s decisions at the elaborative stage were predictably mixed, with some litigants, particularly Native Americans, forced to endure restrictions on their religious exercise. In Lyng v. Northwest Indian Cemetery Protective Association (1988), the Court permitted the Department of the Interior to build roads through sacred burial grounds, rejecting the free exercise claim of the tribes. This was consistent with Court decisions in United States v. Lee (1982) and Bowen v. Roy (1986). In the latter, the Court ruled that compelling Native Americans to have a social security number in order to receive government benefits did not impair their free exercise of religion. In the former case, the Court refused to allow Amish employers to opt out of the social security program because it violated their religious beliefs.

Given normal expectations and stable membership, the Court should impose consistency and stability on the elaborative-stage cases. Policies remain in the elaborative stage for a long period of time as the Court assimilates new members. Stability and consistency, however, are seldom established because of membership changes or the introduction of multiple issues that arise in individual cases (the complex stage). Even marginal changes can upset the existing stability in decision patterns and send mixed or confusing signals to litigants and lower courts. The combination of mixed signals and changes to the ideological composition on the Court may create an environment for major policy change. At this point, the elaborative stage may come to an end, and the Court might exit the issue, return to the episodic stage, or seek the emergence of second-generation doctrine. The Court’s path may be influenced by the number and character of complex-stage cases.

In free exercise cases, the Court continued to use the Sherbert standard but allowed impositions because they were indirect and the government had a compelling interest. Remember that the expectation is that in the elaborative stage, the Court will begin to issue decisions that are less supportive of rights and liberties. The question is why? Because the Court was getting more conservative, there was a question of whether these cases were increasingly being decided in the government’s favor because of the difficulty of the issues raised or because the justices were reexamining the fundamental core precedents. In other words, is the Court still supportive of the central precedent of the emergent stage and merely drawing outer boundaries? Or is the reversal a sign that the Court is reconsidering the landmark decision?

A new Court that is antagonistic to its predecessor’s precedents can begin to reverse decisions at the elaborative stage. The effect is to send clear signals to litigants interested in paring the original doctrine. If the new Court imposes consistency on elaborative-stage cases, it may raise the question of whether the Court is willing to reconsider emergent precedents. Normally, the type of membership change required to achieve this policy devolution is extensive and must involve wholesale changes in the ideological composition of the Court.

Complex

Policy is expected to evolve from the elaborative to the complex stage. In the complex stage, the cases again present the Court with difficult choices. But they are different from the elaborative stage in that these cases introduce some completely different issues in the same dispute. The issue may be attached to other issues by litigants or by justices interested in pursuing certain policy goals. Because of the multiple issues in these cases, a variety of disparate groups are typically involved, complicating the work of the Court. The justices have to decide which issue (and which precedent) governs. For instance, hate speech has two very different issues: Is it a free speech case or a civil rights case? One precedent governs one issue while a different precedent controls the other issue, and this can lead to contradictory results. Indeed, the issues can split traditional allies, whether they be justices or litigants (Walker 1994).

At the complex stage, supporters of the original landmark will attempt to create a new issue if they have the necessary support or try to separate the individual issues to avoid any damage to the core if they do not. For instance, the ACLU tried to separate the civil rights component out of hate speech cases to protect the free speech precedents. Similarly, civil rights groups would downplay the free speech element and focus on harm to the community. During this stage, the general behavioral impact is expected to be instability in individual and institutional decision-making and coalitional patterns. Some members of the Court may decide the case on the basis of one issue, while their colleagues view a different issue as controlling. Thus votes of individual members and decisions of the Court may appear to contradict votes and decisions found in the elaborative-stage cases. The need for consistency in decisions may induce the Court to separate the issues and address them individually. If this represents a new issue, that issue is expected to form its own episodic or emergent stage while the Court returns the original issue to the elaborative stage.

In our free exercise example, there are numerous cases that raised multiple constitutional provisions. Goldman v. Weinberger (1986) and O’Lone v. Shabazz (1987) raised complex-stage multidimensional issues: military regulations and prison security, respectively. Goldman was a complex-stage case because military discipline could dictate the Air Force’s dress code and deny an Orthodox Jew the right to wear a yarmulke. O’Lone involved a similar need for discipline in a prison that permitted some restriction on the free exercise of religion. In cases like this, the Court has to decide whether freedom of religion or prison security should be the most important issue and then apply the standards that govern that area. Other cases involved religious expression in a public forum and bore no small resemblance to the petitions brought by Jehovah’s Witnesses that opened the door to modern free exercise doctrine. Cases raising free exercise questions have allowed the Court to refine its policies regarding the definition, use, and limits of a public forum. Board of Airport Commissioners v. Jews for Jesus (1987) and International Society for Krishna Consciousness v. Lee (1992) involved proselytizing and solicitation efforts in airports. The groups consistently raised free exercise claims, but the Court confined its evaluation to free speech in a manner that was similar to its treatment of cases after Cantwell.

Trinity Lutheran Church v. Comer (2017) is a great example of a dispute that arrived as a complex-stage case with both free exercise and establishment elements. The church had a preschool that was denied funds for its playground under a provision of the Missouri Constitution that forbade aid to religious institutions. The state argued that any public aid violated the establishment clause of the First Amendment, but the Court concentrated on the free exercise claim. In its decision, the Court overturned the state’s decision to deny benefits to the church. The Court ruled that the exclusion of funds from a neutral secular aid program was a violation of the guarantee of free exercise of religion. The dissenters adhered to the establishment clause claim.

Return to Emergent

In the area of free exercise doctrine, the trend of the elaborative- and complex-stage decisions was increasingly restrictive of free exercise claims. It is important to note that the evolution of doctrine is not necessarily an unbroken chain of advancement. The accumulation of membership changes gave the Court a more deferential attitude toward state regulations. These decisions seemed at odds with the core standard, coming from Sherbert, which was protective of free exercise. When such tensions exist, the Court may decide to reexamine the core questions and return the issue to the emergent stage.

In Employment Division, Department of Human Resources of Oregon v. Smith (1990), the Court returned the issue to the emergent stage by abandoning the compelling interest standard of Sherbert v. Verner. Attorneys for Smith attempted to tie his case to Sherbert and Thomas because Smith was denied unemployment compensation after being fired for using peyote in a religious ceremony. Although the majority opinion could have reached the same result without tampering with the existing standard, given the state’s compelling interest in halting the use of drugs, Justice Scalia’s opinion gave the state much wider authority and appeared to revisit the Secular Regulation rule (Long 2000). In doing so, the Court appeared to adopt a two-part test. The first question asks if the regulation of religion exercise is similar to that of secular behavior. If the answer is yes, the Court applies a rational basis test. If the answer is no, the Court uses a compelling interest test. The Court rejected Sherbert and the compelling interest standard, in effect moving the issue back to the emergent stage.

The ACLU could not successfully head off the apparent demise in Smith, but they have supported other groups and individuals challenging state restrictions on religious freedom. While Smith remains the official precedent, the ACLU has had success in winning cases like Church of the Lukumi Babalu Aye, Inc. v. Hialeah (1993) on the merits, thus limiting the potentially negative reach of Smith. The case involved a municipal ordinance against animal sacrifice, a central tenet of the Santeria religion. The Court ruled that Hialeah discriminated against religion and overturned the statute under Smith’s adaptation of a compelling interest test.

Occasionally, the Court’s doctrinal development attracts the attention (and wrath) of elected officials. Under pressure from an impressive array of organized religious groups, Congress intervened to try to reinstate Sherbert as the governing precedent. Congress passed the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) and the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act (RLUIPA), which required courts analyzing free exercise cases to use the substantial burden / compelling interest standard that had been in force since the Sherbert decision (Epp 2009).

The Supreme Court rebuffed congressional efforts in City of Boerne v. Flores (1997) by declaring that it alone had the authority to determine the meaning of the First Amendment. While the Court dismissed the congressional rebuke, the justices were willing to allow Congress to raise the standards for the laws it passed. Thus the Court allowed Congress to bind itself to the more demanding requirements expressed in RFRA. At the same time, state regulations that fall under the Constitution lie outside RFRA and RLUIPA and are governed by the more forgiving Smith standard. Thus the Court established a bifurcated standard where federal statues burdening religions are governed by RFRA’s adaptation of Sherbert, while similar state statues are evaluated under Smith. This bifurcation triggered additional rounds of elaborative-stage litigation as states and communities felt free to restrict the religious freedom of different, often small religious sects.

The most recent complex-stage case to fall under the Smith doctrine was Masterpiece Cakeshop Ltd. v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission (2018). A baker refused on religious grounds to make a wedding cake for a same-sex couple. The Court had to balance the Constitution’s requirement of equal treatment for the gay couple (under the Fourteenth Amendment) with the requirement of free religious exercise of the baker and his free expression (under the First Amendment). Justice Kennedy’s plurality opinion in Masterpiece Cakeshop used the rationale of Smith and Hialeah, claiming that the state commission’s hostility to religion placed the case within the protection of the First Amendment. Kennedy said that the ultimate resolution depended on “further elaboration in the courts.” In other words, the Court would need to continue the evolution of these issues. Given recent personnel changes on the Court and its apparent unenthusiastic application of Smith, conditions may be ripe for the Court to enter a new episodic or emergent stage. It also remains to be seen if the Court, litigants, lower courts, and elected officials will stay on the path established by Smith and these statutory protections.

The shifts between stages are the result of the unique conversation that takes place among the justices and among the Court, lower courts, other branches of government, and various litigants. Shifts from the episodic stage to the emergent stage represent the willingness of the justices to recognize an issue and adopt a policy to address it in subsequent cases. That policy may be the result of suggestions by a lower court or litigant or ideological shifts in the political environment. Moving from the emergent to the elaborative stage indicates the willingness of the Court and litigants to use that policy to address increasingly difficult factual questions within a particular issue. Ultimately, the difficulty of those questions may open the new issue up to conflicts with existing issue and policy areas. These conflicts represent the complex stage of issue and policy development. Here litigants or justices may see the benefit of attaching other issues to the new issue or choosing to focus on one issue over another, oftentimes leading to a new round of evolutionary development of policy and precedent.

Taking a Step Back

While we have focused on the evolution of free exercise of religion doctrine, similar dynamics were and are playing out simultaneously in a number of issue areas. Some of those issue areas, such as freedom of speech and establishment of religion, are closely related and resemble free exercise disputes. Because they have similar doctrinal roots, decisions in one of these areas may have implications for related issues. Once a breakthrough occurs in a new issue area, it may lead to a surge of activity in other areas (Downs 1973, 40-45). When the Court issues a landmark decision, it may lead winning litigants and groups to initiate related litigation and try to transplant the success. Groups that are active in multiple areas of law may attempt to transplant success to another area. Lower courts will borrow the precedent and use it for a related area of law. Justices who are supportive of the landmark may be emboldened to try to extend the original decision to other areas.

The Court’s reconsideration or reversal of a precedent may also start a surge for reversals in other areas. Just as the announcement of Sherbert triggered similar landmarks in other areas, the reversal of a precedent like Sherbert does not occur in a vacuum. Indeed, the end of Sherbert suggested that threats to the Lemon test from the neighboring area of the establishment clause might be imminent. So far, the demise of the Sherbert test has not led to the end of the Lemon test. In recent years, the Court has either avoided or limited its application of the Lemon test in public prayer cases (see Lee v. Weisman (1992) and Town of Greece v. Galloway (2014)), public displays of the Ten Commandments cases (see Van Orden v. Perry (2005)), and various types of parochial school aid cases (Agostini v. Felton (1997) and Zelman v. Simmons-Harris (2002)). However, it is clear that the Court may still revisit the emergent stage and modify or reverse the Lemon test.

This model of issue evolution is also useful in helping understand why precedents that are unpopular manage to survive. Just as Lemon has survived to this point, so have a number of precedents that arrived about the same time as Sherbert. Miranda rights have been undermined with a “public safety” exception and the “inevitability of discovery” exception, but the Court declined the opportunity to reverse it altogether. Mapp has similarly had exceptions, such as “good faith,” which suggest that the core will be reevaluated (Pacelle 2004). Roe has been undermined by a plethora of regulations, but the central precedent remains on the books despite the number of sitting justices who publicly rebuked it. Courts do not often overturn their decisions (Ball 1978); rather, through attrition or exceptions in the elaborative stage, justices who are so inclined might undermine the core precedent. At some point, the Court may return to the emergent stage, but the existing precedent often lasts beyond its predicted demise. Many precedents remain in force because the law is settled, and litigants, citizens, and lower courts know the extent of their rights and duties.

Conclusion

Because the policy goals of the justices are considered the most significant influence on decision-making, research tends to concentrate on them to the exclusion of other factors. This framework of issue evolution suggests that institutional rules and norms (respecting precedent and developing consistency in guiding lower courts) also structure decision-making and doctrinal construction. An examination of free exercise doctrine suggests that the behavior of justices and litigants varies under different conditions and by stage.

Constitutional rights are neither self-defining nor absolute. The creation and development of doctrine demands further rounds of litigation. A given policy is born of related issues and helps create or influence other issues. Landmark decisions and their relevant areas of law trace their doctrinal roots to other substantive areas. As a result, decisions in one area will have ripple effects on other areas.

While justices and litigants have a strong incentive to see their policy designs reflected in the interpretation of the Constitution, they face different constraints and have different opportunities as doctrine evolves. Thus their behavior will vary as a function of the stage of policy evolution. During the episodic stage, the goal is to find a temporary home for the new issue and marry it to a favorable precedent. During the emergent stage, the goal is to hone a standard or test for the new area and make it as strong as possible so it will survive the coming cases. At the elaborative stage, the primary goal is to insulate the core precedent so it is protected and harder to reverse. Finally, in the complex stage, the strategic tactic might be to separate the issues so that particularly difficult cases do not harm the core emergent precedent. When conditions change, litigants and justices may have to develop defensive strategies to protect what they gained in better times. The model also helps explain why, despite the changes in the Court, precedents like Roe, Lemon, Mapp, and Miranda survive.

In some ways, the past is a prologue for free exercise litigation. Footnote four and incorporation opened a policy window, and litigants used the opportunity to change the law. Subsequent changes in the ideological composition of the Court have led to doctrinal retreat, but the process of dismantling doctrine is, like the process of creating it, protracted. It is the nature of spillovers that the retreat that has marked free exercise doctrine spreads to other areas of law, but not completely. The slow nature of change is a function of the need to have stability and predictability in the law, but it is also the result of the purposive behavior of actors who want to protect existing interpretation of the law. In that regard, as Kobylka noted, “it demonstrates the capacity of the law to withstand politically directed efforts at change” (1995, 125).

References

Bailey, Michael A., and Forrest Maltzman. 2011. The Constrained Court: Law, Politics, and the Decisions Justices Make. Princeton: Princeton University Press. (↵ Return)

Baird, Vanessa. 2007. Answering the Call of the Court: How Justices and Litigants Set the Supreme Court Agenda. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Baird, Vanessa. 2004. “The Effect of Politically Salient Decisions on the U.S. Supreme Court’s Agenda.” Journal of Politics 66 (3): 755–72. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Ball, Howard. 1978. Judicial Craftsmanship or Fiat? Direct Overturn by the United States Supreme Court. Westport, CT: Praeger. (↵ Return)

Bartels, Brandon, and Andrew O’Geen. 2015. “The Nature of Legal Change on the U.S. Supreme Court Jurisprudential Regimes Theory and its Alternatives.” American Journal of Political Science 59 (4): 880–95. (↵ Return)

Baum, Lawrence. 2017. Ideology in the Supreme Court. Princeton: Princeton University Press. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Baum, Lawrence. 2006. Judges and their Audiences. Princeton: Princeton University Press. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2) (↵ Return 3)

Baum, Lawrence. 1997. The Puzzle of Judicial Behavior. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. (↵ Return)

Baumgartner, Frank, and Bryan Jones. 1993. Agendas and Instability in American Politics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (↵ Return)

Collins, Paul M., Jr. 2008. Friends of the Supreme Court. New York: Oxford University Press. (↵ Return)

Collins, Paul M., Jr. 2012. “Interest Groups and Their Influence on Judicial Policy.” New Directions in Judicial Politics. Ed. Kevin McGuire. New York: Routledge. (↵ Return)

Corley, Pamela, Paul Collins, and Bryan Calvin. 2011. “Lower Court Influences on U.S. Supreme Court Opinions.” Journal of Politics 73 (1): 31–44. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Cortner, Richard. 1981. The Supreme Court and the Second Bill of Rights: The Fourteenth Amendment and the Nationalization of Civil Rights. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. (↵ Return)

Crenson, Matthew. 1971. The Unpolitics of Air Pollution. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. (↵ Return)

Eisler, Kim Isaac. 1993. A Justice For All: William J. Brennan, Jr. and the Decisions That Transformed America. New York: Simon and Schuster. (↵ Return)

Epp, Charles. 1998. The Rights Revolution: Lawyers, Activists, and Supreme Court in Comparative Perspective. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (↵ Return)

Epp, Garrett. 2009. Peyote v. The State: Religious Freedom on Trial. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. (↵ Return)

Epstein, Lee, and Jack Knight. 1998. The Choices Justices Make. Washington, D.C.: CQ Press. (↵ Return)

Galanter, Marc. 1974. “Why the ‘Haves’ Come Out Ahead: Speculations on the Limits of Legal Change.” Law & Society Review 9 (1): 95–160. (↵ Return)

Gerhardt, Michael J. 2008. “The Power of Precedent.” Oxford: Oxford University Press. (↵ Return)

Hansford, Thomas G., and James F. Spriggs II. 2006. The Politics of Precedent on the U.S. Supreme Court. Princeton: Princeton University Press. (↵ Return)

Hettinger, Virginia, and Stefanie Lindquist. 2012. “Decision Making in the U.S. Court of Appeals: The Determinants of Reversal on Appeal.” In New Directions in Judicial Politics, ed.Kevin McGuire, 126–43. New York: Routledge. (↵ Return)

Hettinger, Virginia Stefanie Lindquist, and Wendy Martinek. 2006. Judging on a Collegial Court: Influences on Federal Appellate Decision-Making. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press. (↵ Return)

Johnson, Timothy R. 2004. Oral Arguments and Decision Making on the United States Supreme Court. Albany: SUNY Press. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Kingdon, John. 1995. Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies (2nd ed). New York: Harper Collins. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Kobylka, Joseph. 1995. “The Mysterious Case of Establishment Clause Litigation: How Organized Litigants Foiled Legal Change.” In Contemplating Courts, ed. Lee Epstein 93–128. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Quarterly. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Long, Carolyn. 2000. Religious Freedom and Indian Rights: The Case of Oregon v. Smith. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. (↵ Return)

Morgan, Richard. 1972. The Supreme Court and Religion. New York: Macmillan. (↵ Return)

Olson, Susan. 1981. “The Political Evolution of Interest Group Litigation.” In Governing Through Courts, eds. Richard Gambitta, Marilyn May, and James Foster, 234–49. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. (↵ Return)

Pacelle, Richard L., Jr. 2018. “Of Political Principles and Legal Principals: The Solicitor General of the United States.” In The Handbook of Judicial Behavior eds. Robert Howard and Kirk Randazzo, 196–220. New York: Routledge Press. (↵ Return)

Pacelle, Richard L., Jr. 2015. The Supreme Court in a Separation of Powers System. New York: RoutledgePress. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Pacelle, Richard L., Jr. 2009. “The Emergence and Evolution of Supreme Court Policy.” In Rethinking U.S. Judicial Politics, ed. Mark Miller, 174–91. New York: Oxford University Press. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Pacelle, Richard L., Jr. 2004. “A Mapp to Legal Change and Policy Retreat: United States v. Leon.” In Creating Constitutional Change, eds. Gregg Ivers and Kevin T. McGuire, 249–63. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press. (↵ Return)

Pacelle, Richard L., Jr. 2003. Between Law and Politics: The Solicitor General and the Structuring of Race, Gender, and Reproductive Rights Litigation. College Station: Texas A&M University Press. (↵ Return)

Pacelle, Richard L., Jr. 1991. The Transformation of the Supreme Court’s Agenda: From the New Deal to the Reagan Administration. Boulder: Westview Press. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2) (↵ Return 3) (↵ Return 4) (↵ Return 5)

Peters, Shawn Francis. 2000. Judging Jehovah’s Witnesses: Religious Persecution and the Dawn of the Rights Revolution. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Richards, Mark J., and Herbert M. Kritzer. 2002. “Jurisprudential Regimes in Supreme Court Decision Making.” American Political Science Review 96 (2): 305–320. (↵ Return)

Sunstein, Cass. 1999. One Case at a Time: Judicial Minimalism on the Supreme Court. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. (↵ Return)

Teles, Steven. 2008. The Rise of the Conservative Legal Movement: The Battle for Control of the Law. Princeton: Princeton University Press. (↵ Return)

Wahlbeck, Paul. 1997. “The Life of the Law: Judicial Politics and Legal Change.” Journal of Politics 59 (3): 778–802. (↵ Return)

Walker, Samuel. 1994. Hate Speech: The History of an American Controversy. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. (↵ Return)

Walker, Samuel. 1990. In Defense of American Liberties: A History of the ACLU. New York: Oxford University Press. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Wasby, Stephen. 1995. Race Relations Litigation in an Age of Complexity. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press. (↵ Return)

Westerland, Chad; Jeffrey Segal, Lee Epstein, Charles Cameron, and Scott Comparato 2010. “Strategic Defiance and Compliance in the U.S. Courts of Appeals” American Journal of Political Science 54 (4): 891–905. (↵ Return)

Zick, Timothy 2018. The Dynamic Free Speech Clause: Free Speech and its Relations to Other Constitutional Rights. New York: Oxford University Press. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2) (↵ Return 3)

Class Activity

Consider the following complex-stage cases. What are the competing issues found in these cases?

- Nebraska Press Association v. Stuart (1976): freedom of the press (First Amendment) and criminal procedure (Sixth Amendment)

- RAV v. City of St. Paul (1992): civil rights, equal protection (Fourteenth Amendment), and freedom of speech (First Amendment)

- JEB v. Alabama (1994): criminal procedure (Sixth Amendment) and gender discrimination (Fourteenth Amendment)

- Rosenberger v. University of Virginia (1995): freedom of speech and freedom of religion

Often after making a landmark decision, the Court turns to related issues. In 1940 in Cantwell v. Connecticut, the Supreme Court began the process of expanding protections for free exercise of religion. In the next decade, they would expand other rights. Give some examples (see below):

- Everson v. Board of Education (1946)

- West Virginia Board of Education v. Barnette (1943)

- Shelley v. Kraemer (1948)

- Sweatt v. Painter (1950)

List and briefly describe the various constitutional protections found in the First Amendment. The Court originally treated them in a similar fashion and later refined the individual tests and standards. Why do you think the Supreme Court addresses these different issues with different doctrines/policies across time and between issues?

Here are examples of different free speech tests, such as clear and present danger and time and place and manner:

- Sherbert test and Smith test

- Lemon test

- New York Times test (libel)

- Memoirs and Miller test (obscenity)

- O’Brien test

Consider the Supreme Court case of Trinity Lutheran Church of Columbia, Inc. v. Comer (2017). Explain the different issues addressed by the majority and dissenting opinions and what doctrine/policies the justices used to resolve those issues. What factors explain the different approaches to the case (i.e., legal or political differences)? In your opinion, which opinion appeared to be more true to precedent? Does your answer match your own beliefs about this case?

Consider a legal dispute in process: East Lansing, Michigan, is barring an orchard owner from participating at the city farm market because the owner does not support same-sex marriage and posted that belief on Facebook. Based only on the post, the city denied the owner a spot at the market.

Explain how this case involves the following issues:

- Free press

- Free speech

- Religious exercise

- Establishment clause

- Equal protection

Please provide case year.