Decision Making

19 Constitutional Interpretation Styles of US Supreme Court Justices

Adam G. Rutkowski

Studies of US Supreme Court decision-making often describe justices’ votes (decisions) as either liberal or conservative. This is understandable given that a justice’s ideology (how liberal or conservative they are) is consistently shown to be a significant predictor of his or her votes on the Court (Segal and Spaeth 2002). While justices have their ideological preferences, they also have their own unique ways of interpreting the Constitution. For example, the late conservative Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia was a textualist, believing that one should only look at the text of the relevant provision when applying the Constitution to a case (Scalia and Garner 2012; Scalia 1998). His jurisprudential and ideological opposite, the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, argued that interpretations of the Constitution should adapt to a changing United States (De Hart 2018).

When Justice Ginsburg wrote an opinion, she did not simply write, “I am a liberal, therefore I vote in a liberal way in this case.” Instead, she provided a detailed opinion in which she interpreted the Constitution and relevant laws and applied that interpretation to the case; there was legal reasoning behind her decision. While ideology may have informed her decisions, her interpretation style should not be overlooked as a distinct characteristic.

Scholars have produced numerous quantitative studies concerning the effects of ideology on US Supreme Court justices’ decision-making, but there have been few, if any, quantitative analyses of the effects of justices’ constitutional interpretation styles. This shortcoming is most likely due to the lack of a measure of this important concept. This chapter develops a measure of constitutional interpretation style for justices serving on the Supreme Court from 1946 to 2017 and applies the measure to justices’ votes in Fourth Amendment cases. Results suggest that these styles matter in predicting judicial decision-making, although their effects may be partially masked by the way scholars typically consider judicial decision-making and outputs.

How Do Judges Make Decisions?

Scholars have identified three primary models of judicial decision-making: legal, attitudinal, and strategic. The earliest of the three, the legal model asserts that judges are neutral arbiters of the law (Maveety 2003; Levi 1949). According to this model, judges decide cases in light of the facts in relation to precedent (existing case law), plain meaning of the Constitution and statutes, and the intent of the legislative branch and Constitutional framers (Segal and Spaeth 2002).

Over time, scholars became less satisfied with this black-and-white picture of judicial decision-making. Research revealed that justices consistently voted in ways that could be placed on a left-right ideological spectrum (Schubert 1968; Pritchett 1948). These discoveries led to the development of the attitudinal model, which asserts that judges decide cases in light of the facts in relation to their ideological values and attitudes (Segal and Spaeth 2002). In other words, judges decide cases based on their views about the relevant law and the parties in a suit (Spaeth 1972). Therefore, “private attitudes become public law” (Pritchett 1941).

It is important to note that law still matters in the attitudinal model. Studies show that justices’ preferences are constrained by precedent, judicial review, and adherence to constitutional provisions when they make decisions (Bailey and Maltzman 2008; Spriggs and Hansford 2001). Justices’ attitudes and the law are thus in a conditional relationship; what judges want to do is constrained by what they can do under the law (Gibson 1978).

The idea of the constrained justice is central to the strategic model of judicial decision-making. While justices may have their own preferences, they are in a state of interdependence with their colleagues and other branches of government (Epstein and Knight 1998; Murphy 1964). In order to “win” the final outcome of the case, they may have to compromise in other areas, such as opinion content. Constraints on justices’ preferences can come from sources both internal (e.g., collegial relations; interbranch relations) and external (e.g., public opinion; interest groups) (Baum 1998).

As this discussion illustrates, one particular model of decision-making does not have all the answers. Instead, it is important to combine elements of each theory to provide a more wholesale account of judicial decision-making. It is from this place that this chapter proceeds—recognizing that while attitudes may be important to justices, how they view and interpret the Constitution also affects their decision-making.

Constitutional Interpretation Styles

While seldom discussed in studies on judicial decision-making, constitutional interpretation style is an important and relevant judicial characteristic to consider. As this chapter will discuss in subsequent sections, interpretive styles are often mentioned during the nomination and confirmation process—especially for nominations to the US Supreme Court. These styles are part of the public discourse about nominees and may serve as cues for both the president and senators, helping them predict a nominee’s future actions. Further, as discussed in the introduction, interpretation styles are used as the bases for justices’ decisions. What follows is a brief overview of common interpretation styles.

Typically, interpretation styles are described as either originalist or progressive (Tribe 1995; Dodson 2008). The three primary originalist styles identified are original intent, textualism, and strict constructionism. Original intent relies on what the framers of the Constitution intended a clause to mean when they wrote the document (Segal and Spaeth 2002; Gillman et al. 2017). Justices subscribing to this method believe that the framers’ intentions should always be considered and respected (Powell 1985; Bork 1997; Kirby 2000). Textualism relies on the text of the Constitution itself. This style—made famous by the late justice Antonin Scalia—focuses on the relationships between words and the commonly understood meanings of those words both at the time the Constitution was written and the present day (Perry 1985; Tushnet 1985; Scalia 1998; Whittington 1999, 2004; Gillman et al. 2017). Finally, strict constructionism is a narrower form of textualism. This style limits constitutional interpretation to the clauses enumerated in the Constitution (Whittington 1999; Gillman et al. 2017).

A more progressive style of interpretation treats the Constitution as a living document (Marshall 1987; Starkey 2012). This style advocates for a Constitution that “adapts to changing circumstances and evolves over time” (Dodson 2008, 1320). When the Constitution is not explicit on an issue, clauses of the constitution and other statutes can be read to find their “spirit”; this spirit can then be applied to the case. Because America changes rapidly, interpretations of a document written over two hundred years ago should adapt.

Measuring Constitutional Interpretation Style

While scholars often describe a justice as a textualist, or believing the Constitution is a living document, no quantitative measure of interpretation style exists. The primary goal of this chapter is to develop such a measure. Segal and Cover (1989) measured justices’ ideological preferences using newspaper editorials in order to capture a justices’ perceived ideology at the time of their confirmation.[1] It is in this spirit that I set about coding constitutional interpretation style. Because the editorials often quote the justices describing how they interpret the Constitution, this method provides a direct measure of interpretation style. Further, choosing editorials provides a manageable number of succinct documents written during a finite nomination period. In other words, it avoids the problems of studying countless justice biographies, memoirs, and interviews.

In order to avoid bias from politically motivated writers, Segal and Cover (1989) used two newspapers with a consistently liberal slant over time (the New York Times and the Washington Post) and two with a consistently conservative slant over time (the Chicago Tribune and the Los Angeles Times). They coded various paragraphs of editorials for statements that were either liberal, moderate, conservative, or none of the above. Based on the total number of editorial statements, they ultimately place justices on a continuum of ideological value scores ranging from 0 (unanimously liberal) to +1 (unanimously conservative).

While my coding of interpretive style follows Segal and Cover’s methods as closely as possible, some adaptations were made. The same two liberal newspapers were coded (the New York Times and the Washington Post), and one of the same conservative newspapers was used (the Los Angeles Times). However, the Chicago Tribune archives are not readily available electronically. Therefore, I used the Wall Street Journal, another conservative-leaning paper, in its place (Wagner and Collins 2014).

I coded five different categories of constitutional interpretation style and treated them as dichotomous variables. Therefore, a justice was coded as a (1) if he or she possessed a certain style and a (0) if he or she did not. The categories I use here are living document, textualist, original intent, other originalist, and progressive. Although scholars identify strict constructionism as an originalist constitutional interpretation style, only one justice in my study was called a strict constructionist by one of the four papers. Therefore, I created the other originalist category for this justice and others not fitting the rigid originalist categories. I created the progressive category to capture justices who have a progressive interpretive style but were not explicitly said to interpret the Constitution as a living document in the editorials.

To reduce bias in the coding, the following steps were taken. First, I coded newspaper editorials from the four aforementioned newspapers that were written during the time period six months prior to their nomination until the day of their confirmation. After coding all thirty-seven justices in the date range, final determinations were made using strict cutoffs. In order to ultimately be assigned to a style, the justice had to be coded as that style for at least three of the four papers used. This threshold provides a more balanced measurement, as it picks up liberal-leaning and conservative-leaning papers. It is also important to note that the categories are mutually exclusive. In this coding framework, a justice cannot belong to more than one constitutional interpretation style. The editorials did not ascribe more than one interpretation style to any of the thirty-seven justices. Table 1 provides more information on my coding framework and how I made final coding decisions.

For even more clarification, consider the following coding example. In a majority of the editorials, Justice Scalia was described as a defender of the words of the Constitution. Additionally, he was often quoted as saying that judicial decisions must be guided by the Constitution’s text. Because these statements belong to the textualism category, Justice Scalia was marked as a (1) in the textualist style and a (0) in the other five categories.

| Interpretation style | Common phrases from editorials |

|---|---|

| Living document |

|

| Textualist |

|

| Original intent |

|

| Other originalist |

|

| Progressive |

|

Table 1. Coding framework

Table 2 reports each justice grouped alphabetically by their perceived preconfirmation constitutional interpretation style. The number of editorials coded for each justice is included in parentheses.[2]

| Living document | Textualist | Original intent | Other originalist | Progressive |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black (17)

Brennan (18) Breyer (17) Fortas (7) Frankfurter (9) Ginsburg (14) Goldberg (10) Harlan (16) Jackson (10) Kagan (23) Marshall (10) Minton (9) Murphy (8) Reed (4) Rutledge (4) Souter (19) Stevens (6) Warren (19) |

Burger (16)

Gorsuch (17) Scalia (18) |

Kennedy (31)

Rehnquist (9) Stewart (10) |

Alito (14)

Blackmun (6) O’Connor (17) Powell (9) Roberts (16) Thomas (41) Whittaker (4) |

Douglas (6)

Sotomayor (19) |

Table 2. Justices’ constitutional interpretation styles

The table above underscores the importance of constitutional interpretation style as a judicial characteristic; indeed, it is clear that editorials use these explicit styles to describe nominees to the nation’s highest court. It is apparent that the living document category contains justices often considered more liberal, while the textualist, original intent, and other originalist categories contain the more conservative justices. Perhaps surprisingly, the most variation in interpretation style is found in these conservative justices. While Scalia was identified as a textualist, Rehnquist was matched with original intent, and O’Connor was painted as a general originalist. All these justices are considered conservative, but each was said to have a distinct constitutional interpretation style. The following application section speaks further to this variation among conservative justices.

It is important to remember that these categorizations were made based on editorials written before the justices’ confirmations. It is possible that the justices shift their styles over time, or that they have different styles for different issue areas. For example, Justice Hugo Black, identified above as a living document justice, was sometimes considered a “literalist”—especially in cases concerning the First Amendment (Lewis 1986). My measure seeks to capture an overarching interpretation style and does not account for issue-specific or temporal nuances.

An Application: Justices’ Votes in Fourth Amendment Cases

With a method of measuring constitutional interpretation style in hand, the next step is to apply it to judicial behavior. For this initial application, I choose to analyze how justices’ constitutional interpretation styles affect their decisions in Fourth Amendment cases. My reasons for analyzing cases on the Fourth Amendment—which protects citizens from unreasonable searches and seizures—are twofold. First, scholars assert that Fourth Amendment cases are rarely clear-cut and that justices interpret this amendment in many different ways (Amar 1994; Dworkin 1973). The varying interpretations of the Fourth Amendment present on the Court make it a natural first issue area to explore. Second, Fourth Amendment cases were often used in seminal judicial politics scholarship on the attitudinal model and fact patterning models (Segal and Spaeth 2002; Segal 1986).

In this application, I theorize that justices’ constitutional interpretation styles should affect their voting independently of other judicial characteristics such as ideology. How can justices with different interpretation styles be expected to vote? In this application section, I offer hypotheses and corresponding theoretical explanations based on the writings of legal scholars.

Fourth Amendment scholars are in agreement that originalist justices should be expected to rule in favor of the government in disputes about searches and seizures. Amar (2000) asserts that the Fourth Amendment was not meant to be a protection against warrantless or unreasonable searches, but rather a protection against unspecific warrants. Other scholars agree that the modern conception of unreasonable searches and seizures is “the product of post-framing developments that the Framers did not anticipate” (Davies 1999, 552). In this view of academics, originalists should only rule against searches and seizures if the warrants are not specific.

The problem with this literature is that it does not distinguish between the types of originalists identified in the previous section—textualism, original intent, and strict construction. These scholars speak of originalism broadly but do not elaborate on which specific type of originalist they expect to rule in favor of the government. I surmise that they are speaking of original intent because they are discussing what the framers meant. These scholars assert the original understanding of the Fourth Amendment is that warrantless searches are not unreasonable; only nonspecific warrants are problematic.

While it is clear that justices subscribing to original intent should more often vote in favor of the government, it is less clear how textualist justices should rule. Amar (1994) asserts that there is a discrepancy between what the words of the Fourth Amendment mean and what they actually say. Therefore, if the original intent justices are comfortable with warrantless searches—which is what scholars have identified the amendment to mean at the founding—then textualists should consider warrantless searches to be unreasonable. Textualists are more concerned about reasonableness of searches and seizures, and thus should uphold protections for individuals (Amar 1994).

The other originalist interpretation style identified in the literature is strict construction. However, this style is rarely ascribed to justices (for further discussion, see the data and measures section). As I discuss later in the paper, I create a category of “other-originalists.” These are justices with a conservative interpretation style that does not fit into original intent or textualism. Because this is a less precise category, formulating a theory of how they should vote is more difficult. Therefore, I do not include a theoretical expectation of how these justices should vote.

Opposite these conservative interpretation styles are justices with styles holding that the Constitution is a living document. Justices who view the Constitution in this manner are more likely to read into the text to find protections for individuals and are not likely to rule in favor of the government (Balkin 2009; Dodson 2008). This has also been shown in Fourth Amendment cases. Justices with a flexible outlook on the Constitution are more likely to “beef up” Fourth Amendment protections for individual plaintiffs (Amar 2000, 761).

Because of the prevalence of the attitudinal model in judicial politics literature (see Lewis and Rose 2014; Boyd et al. 2010; Segal and Spaeth 2002; and George and Epstein 1992), I include a hypothesis concerning ideology. I expect that even when controlling for interpretation styles, ideology will still have a significant effect. Spaeth et al. (2018, SCDB codebook) assert that ideologically liberal decisions are typically those that rule in favor of the individual rather than the government. Thus it is expected that a more liberal justice should more often vote in favor of individuals in Fourth Amendment cases.

In the following section, I discuss the operationalization of concepts that will be utilized to test these hypotheses.

Data and Measurement

For this application, I analyze the 341 Fourth Amendment cases decided by the Supreme Court between 1946 and 2017. The unit of analysis is a justice’s vote in a particular case. The cases were sourced from Spaeth et al.’s (2018) US Supreme Court database (SCDB).

The dependent variable employed is progovernment. The data for this variable is gathered from the SCDB and is a measure of whether a justices’ decision is progovernment (conservative) or not (i.e., proindividual or liberal). This dichotomous variable is coded 1 for a conservative (progovernment) decision and 0 for a liberal (proindividual) decision. Of the 341 Fourth Amendment cases in the SCDB from 1946 to 2017, 203 were decided conservatively, and 138 were decided liberally.

The primary concept of interest in this chapter is constitutional interpretation style. This concept, discussed in greater detail in earlier sections, captures a justice’s perceived preconfirmation constitutional interpretation style as revealed in editorials written about the justice when he or she was a nominee to the Court. This concept is indicated by five separate dichotomous variables: original intent, textualism, other originalist, progressive, and living document. As noted in the measure development section, these categories are mutually exclusive, meaning that each justice can only be assigned to one of the five categories.

The second independent variable, ideology, is measured with Segal-Cover scores (1989) ranging from 0 (extremely liberal) to 1 (extremely conservative). As discussed earlier in the chapter, these scores capture the perceived ideology of Supreme Court nominees.[3]

Prior prosecutorial experience is included as a control variable. It is widely argued that background characteristics of judges such as prior prosecutorial experience affect case outcomes (Brace and Hall 1997; Ashenfelter et al. 1995; Ulmer 1961, 1973). Tate (1981) found that justices who worked as prosecutors in the past vote less often in favor of individuals and more often in favor of the government. This could be because the justices are accustomed to representing the government’s position and learn to see cases from that perspective (Tate and Handberg 1991).

Experience is a dichotomous measure coded from information in Epstein et al.’s (2020) US Supreme Court Justices Database. This database contains a wealth of knowledge about justices’ background characteristics. Several of these variables convey justices’ prosecutorial experience at various levels. I code a justice as (1) if they have prior prosecutorial experience at any level (local, state, or federal) and (0) if they do not. In the dataset of 37 justices, 22 have prior prosecutorial experience.

Results

As discussed in the application section, justices subscribing to original intent and general originalism are expected to vote more often in favor of the government, while justices who are textualists are expected to vote more often in favor of the individual. Justices who view the Constitution as a living document and justices with a generally progressive interpretation style are also expected to vote more often in favor of the individual. Further, justices with conservative ideologies and prior prosecutorial experience are expected to vote more often in favor of the government.

| Progovernment = 1 | Model 1 |

|---|---|

| Original intent | 1.35**

(.31) |

| Textualism | 1.03**

(.47) |

| Other originalist | 1.27**

(.40) |

| Progressive | -.49

(.52) |

| Living document | Baseline |

| Ideology | -1.22*

(.65) |

| Prosecutorial experience | .54**

(.27) |

| Constant | -.15

(.57) |

Table 3. Results of logistic regression

Note: Table 3 reports coefficients with corresponding standard errors in parentheses. ** p ≤ .05, * p ≤ .10, N = 3,793. Standard errors are robust and clustered around each justice. [4]

Table 3 presents results from a logistic regression. Remember that each interpretation style is treated as a separate dichotomous variable. In the model, the living document category is held as the baseline, meaning that results for the interpretation styles are interpreted in relation to justices with this interpretation style. The results from this model suggest that subscribing to textualism, original intent, or general originalism (i.e., other originalist) increases the likelihood of voting in favor of the government, as the coefficients for those variables are positive and statistically significant at the 0.05 level. Note that the coefficients for original intent, textualism, and other originalist are similar in magnitude. This suggests that instead of there being variation between justices with the originalist interpretive styles, these justices form a camp and vote more often in favor of the government—even when controlling for ideology and prior prosecutorial experience.

Conversely, I can surmise that justices believing the Constitution is a living document are more likely to vote in favor of the individual, as expected by H2. Further, the lack of significance in the progressive variable suggests that those justices vote similarly to living document justices.

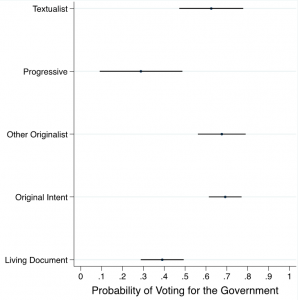

Figure 1 plots predicted probabilities of voting in favor of the government for justices with each interpretation style. While the results from table 3 allow for the direction and significance of effects to be determined, predicted probabilities provide a more substantive way to interpret the regression results.

Note: This graph shows predicted probabilities of voting in favor of the government for justices with each interpretation style. Ideology and prior prosecutorial experience are controlled.

I will first consider the three originalist styles—textualist, original intent, and other originalist. A textualist justice has a 63 percent probability of voting in favor of the government in these cases. Justices with the other originalist style and original intent style have a 68 percent and 69 percent probability of voting in favor of the government, respectively. Although textualist justices vote less often in favor of the government, the difference is statistically insignificant (the confidence intervals overlap in the graph). Therefore, H1 is unsupported. However, it is interesting to note that these interpretation styles have significant effects even when ideology is controlled.

It is striking to see the stark differences in how living document justices vote in relation to justices with an originalist style. A justice viewing the Constitution as a living document has only a 39 percent probability of voting in favor of the government. Further, justices with the progressive interpretation style only have a 29 percent probability of supporting the government’s position. Therefore, it is clear that H2 receives strong support in this model.

My ideology hypothesis (H3) is also supported. Table 3 conveys that a more ideologically liberal justice is less likely to vote in favor of the government, as indicated by the negatively signed coefficient. Conversely, it can be assumed that a more conservative justice is more likely to vote in favor of the government. Also, it is evident that justices with prior prosecutorial experience are more likely to rule in favor of the government, as the coefficient for experience is positively signed and statistically significant at the .05 level.

The results from table 3 and figure 1 show that despite legal scholars’ purported differences in the originalist constitutional interpretation styles (original intent, textualism, and other originalist), these justices usually form a camp to vote in favor of the government, at least in Fourth Amendment cases. Likewise, living document and progressive justices form a camp and usually vote in favor of the individual. In sum, justices with a progressive interpretation style of the Constitution vote in favor of the individual, and justices with an originalist interpretation style of the Constitution vote more often in favor of the government.

Future Application: Studying Supreme Court Opinions

This chapter developed a novel way of measuring interpretation style and applied it to Fourth Amendment cases. The natural place to start with an application of the interpretation style variables was judicial voting. By their very nature, Supreme Court justice votes are dichotomous. This dichotomy provides for clean research designs but is limited by a lack of variation. Indeed, the lack of variation found among justices with originalist interpretation styles is probably due to the fact that the dichotomous nature of the dependent variable makes it difficult to observe differences.

The next step is to move past dichotomous votes and analyze the actual content of the opinions. Opinion language is important to consider because it reflects how the law develops, not just who wins or loses. The language of these opinions becomes precedent and is used in rationales of future court decisions in both federal trial and appellate courts. Differences in originalist interpretation styles may shine more easily through the language used by these justices when they write opinions. I illustrate this possibility in the following anecdotal example.

Consider Bertine v. Colorado (1987), a case decided 7–2 by the Rehnquist Court. Chief Justice Rehnquist, identified as an original intent justice in editorials, authored the conservative-leaning majority opinion. In the opinion, he asserts that reasonable searches are acceptable even without a warrant. This interpretation is similar to Amar’s (1994, 2000) expectation of how original intent justices should interpret the Fourth Amendment. Now consider Murray v. United States (1988), a case decided 4–3 by the Rehnquist Court. Justice Scalia, a known textualist, wrote the conservative-leaning majority opinion. In his writing, he places controlling weight on the words of the Fourth Amendment and decides that the words of the disputed policy supported the government’s claims. It is important to note that Scalia joined the majority opinion written by Rehnquist, and Rehnquist joined the majority opinion written by Scalia. So although they both agreed on the outcome of each case, they each used different language and arguments to form their conclusions. These different arguments can form the basis of rationales used by other judges and justices in the future.

The challenge with studying interpretation styles via opinions is coming up with a systematic way of analyzing them. Text analysis software would have to be used, and key words related to the interpretation styles would need to be developed. Once the key word lists were developed, software could automatically analyze the opinions to find those particular words. I leave this mention of studying opinion texts as food for thought and encourage scholars to pursue this research path.

Discussion and Conclusion

This chapter developed a measure capturing Supreme Court justices’ perceived, preconfirmation constitutional interpretation styles. The primary styles identified were original intent, textualism, and viewing the Constitution as a living document. With the interpretation style variables in hand, the chapter applied them to justice voting in Fourth Amendment cases to discover whether these interpretation styles affect justices’ votes.

The styles did matter, but not in the ways expected for this particular Fourth Amendment application. No variation was found among the voting of textualist and original intent justices; instead, each consistently voted in favor of the government. This runs contrary to Amar’s (1994, 2000) and others’ expectations of variation. Thus there seems to be a discrepancy between legal scholars’ arguments and the realities of Fourth Amendment case voting. However, the constitutional interpretation style variables were consistently significant in the models, suggesting that they affect decision-making independently of ideology.

On the other hand—and perhaps unsurprisingly—justices who view the Constitution as a living document ruled more often in favor of the individual compared to the originalist styles. Although justices seem to divide themselves into simple progovernment/proindividual voting camps, I think further consideration of the effects of constitutional interpretation style is warranted.

One method of considering these effects further could be to apply the style variable to another set of cases. For example, maybe all hypotheses would be supported in First Amendment cases of the Supreme Court. This amendment may allow the hypothesized variation between textualists/other originalists and original intent justices to be seen. While it is beyond the scope of this chapter to explore this possibility, this suggestion provides an interesting avenue for future research.

Another factor probably masking variation is the dichotomous nature of the dependent variable. Studying votes does not take into account the actual language of the opinions. Opinion language is important to consider because it reflects how the law develops, not just who wins or loses. The section above highlights the importance of considering opinion language by highlighting two particular cases. The anecdotal evidence provided there could be a cue that it is time to reconsider the black-and-white dichotomy of voting and analyze whether justices with different conservative constitutional interpretation styles are writing opinions in different ways.

Future work should also consider more sophisticated ways to measure interpretation styles. Just as Martin and Quinn (2002) sought to provide a dynamic measure of ideology that improved upon Segal and Cover’s (1989) static scores, it seems plausible that a similar development could happen for interpretation styles. While the strategy of coding interpretation style outlined in this chapter is useful, it is limited by the fact that it reflects the perceived interpretation style at the time of their nomination to the Supreme Court. It does not take into account issue-specific differences or changes that can occur over time. While a daunting task, having a dynamic measure of interpretation style would be incredibly beneficial for further understanding Supreme Court behavior.

Overall, this chapter provides a measure of constitutional interpretation style that can be applied to many issue areas and many areas of judicial behavior. It is important to note that this is only the starting point on a long road to understanding how justices’ views of the Constitution affect their behavior. The interpretation measure and the application presented in this chapter provide useful first steps toward this worthy task.

Student Activities

- This chapter addresses the importance of considering aspects of both the legal and attitudinal models in studies on judicial decision-making. The component of the legal model addressed is constitutional interpretation style. Justice ideology was included to account for the attitudinal model. In a one- to two-page essay, compare and contrast constitutional interpretation style and ideology. Further, discuss how these two concepts affect each other. Does judicial ideology influence interpretation style, or does judicial interpretation style influence ideology? Justify your response with both academic sources and practical examples.

- Refer to the section entitled “Future Application: Studying Supreme Court Opinions.” This section highlights the importance of considering interpretation styles in the context of opinion content but recognizes the challenges this would present. In small groups, develop a research plan that allows for systematic analysis of opinion content that could help reveal effects of constitutional interpretation style. What “tools” would a researcher need to complete this task? How long might such a project take? What are some challenges of such a project? What could make these challenges easier to overcome?

References

Amar, Akhil Reed. 1994. “Fourth Amendment First Principles.” Harvard Law Review 107 (4): 757–819.

———. 2000. The Bill of Rights: Creation and Reconstruction. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Ashenfelter, Orley, Theodore Eisenberg, and Stewart J. Schwab. 1995. “Politics and the Judiciary: The Influence of Judicial Background on Case Outcomes.” Journal of Legal Studies 24 (2): 257–81.

Bailey, Michael A., and Forrest Maltzman. 2008. “Does Legal Doctrine Matter? Unpacking Law and Policy Preferences on the US Supreme Court.” American Political Science Review 102 (3): 369–84.

Balkin, Jack M. 2009. “Framework Originalism and the Living Constitution.” Northwestern University Law Review 103 (2): 549–614.

Baum, Lawrence. 1998. The Puzzle of Judicial Behavior. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Bork, Robert. 1997. The Tempting of America. Tampa: Free Press.

Boyd, Christina L., Lee Epstein, and Andrew D. Martin. 2010. “Untangling the Causal Effects of Sex on Judging.” American Journal of Political Science 54 (2): 389–411.

Brace, Paul, and Melinda Gann Hall. 1997. “The Interplay of Preferences, Case Facts, Context, and Structure in the Politics of Judicial Choice.” Journal of Politics 59 (November): 1206–31.

Colorado v. Bertine. 1987. 479 U.S. 367.

Davies, Thomas Y. 1999. “Recovering the Original Fourth Amendment.” Michigan Law Review 98 (3): 547–750.

De Hart, Jane Sheron. 2018. Ruth Bader Ginsburg: A Life. New York: Knopf.

Dworkin, R. B. 1973. “Fact Style Adjudication and the Fourth Amendment: The Limits of Lawyering.” Indiana Law Journal 48:329–68.

Dodson, Scott. 2008. “A Darwinist View of the Living Constitution.” Vanderbilt Law Review 61:1319–47.

Epstein, Lee, and Jack Knight. 1998. The Choices Justices Make. Washington, DC: CQ Press.

Epstein, Lee, Andrew D. Martin, Kevin M. Quinn, and Jeffrey A. Segal. 2007. “Ideological Drift Among Supreme Court Justices: Who, When, and How Important?” Northwestern University Law Review 101 (4): 1483–542.

Epstein, Lee, Thomas G. Walker, Nancy Staudt, Scott Hendrickson, and Jason Roberts. 2020. “The US Supreme Court Justices Database.” September 19, 2020. http://epstein.wustl.edu/research/justicesdata.html.

George, Tracey E., and Lee Epstein. 1992. “On the Nature of Supreme Court Decision Making.” American Political Science Review 86 (2): 323–37.

Gibson, James L. 1978. “Judges’ Role Orientations, Attitudes, and Decisions: An Interactive Model.” American Political Science Review 72 (3): 911–24.

Gillman, Howard, Mark A. Graber, and Keith E. Whittington. 2017. American Constitutionalism. Vol. 2, Rights and Liberties. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hair, Joseph F., Jr., William C. Black, Barry J. Babin, and Rolph E. Anderson. 2009. Multivariate Data Analysis. 7th ed. New York: Pearson.

Kirby, Michael. 2000. “Constitutional Interpretation and Original Intent: A Form of Ancestor Worship.” Melbourne University Law Review 24:1–14.

Levi, Edward. 1949. An Introduction to Legal Reasoning. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lewis, Anthony. 1986. “Justice Black and the First Amendment.” Alabama Law Review 38:289.

Lewis, David A., and Roger P. Rose. 2014. “Case Salience and the Attitudinal Model: An Analysis of Ordered and Unanimous Votes on the Rehnquist Court.” Justice System Journal 35 (1): 27–44.

Marshall, Thurgood. 1987. “The Constitution: A Living Document.” Howard Law Journal 30:915–20.

Martin, Andrew D., and Kevin M. Quinn. 2002. “Dynamic Ideal Point Estimation via Markov Chain Monte Carlo for the US Supreme Court, 1953–1959.” Political Analysis 10:134–53.

Maveety, Nancy L. 2003. The Pioneers of Judicial Behavior. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Murphy, Walter F. 1964. Elements of Judicial Strategy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Murray v. United States. 1988. 487 U.S. 533.

Perry, Michael J. 1985. “The Authority of Text, Tradition, and Reason: A Theory of Constitutional Interpretation.” Southern California Law Review 58:1–53.

Powell, H. Jefferson. 1985. “The Original Understanding of Original Intent.” Harvard Law Review 98 (5): 885–948.

Pritchett, C. Herman. 1941. “Divisions of Opinion Among Justices of the US Supreme Court, 1939–1941.” American Political Science Review 35 (5): 890–98.

———. 1948. The Roosevelt Court: A Study in Judicial Politics and Values, 1937–1947. New York: Macmillan.

Ringle, Christian M., Sven Wende, and Jan-Michael Becker. 2015. SmartPLS 3. http://www.smartpls.com.

Scalia, Antonin. 1998. A Matter of Interpretation: Federal Courts and the Law. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Scalia, Antonin, and Bryan A. Garner. 2012. Reading Law: The Interpretation of Legal Texts. Saint Paul, MN: Thomson/West Publishers.

Schubert, Glendon A. 1968. The Judicial Mind: The Attitudes and Ideologies of Supreme Court Justices 1946–1963. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press.

Segal, Jeffrey A. 1986. “Predicting Supreme Court Cases Probabilistically: The Search and Seizure Cases, 1962–1984.” American Political Science Review 78:891–900.

Segal, Jeffrey A., and Albert D. Cover. 1989. “Ideological Values and the Votes of US Supreme Court Justices.” American Political Science Review 83:557–65.

Segal, Jeffrey A., and Harold J. Spaeth. 2002. The Supreme Court and the Attitudinal Model Revisited. Cambridge: University of Cambridge Press.

Spaeth, Harold J. 1972. An Introduction to Supreme Court Decision Making: Revised Edition. New York: Chandler.

Spaeth, Harold J., Lee Epstein, et al. 2017. Supreme Court Database, Version 2017, Release 1. http://supremecourtdatabase.org.

Spriggs, James E., III, and Thomas Hansford. 2001. “Explaining the Overruling of US Supreme Court Precedent.” Journal of Politics 63:1091–111.

Starkey, Brando Simeo. 2012. “A Failure of the Fourth Amendment & Equal Protections’ Promise: How the Equal Protection Clause Can Change Discriminatory Stop and Frisk Policies.” Michigan Journal of Race and Law 18:131–87.

Tate, C. Neal. 1981. “Personal Attribute Models of the Voting Behavior of U.S. Supreme Court Justices: Liberalism in Civil Liberties and Economics Decisions, 1946–1978.” American Political Science Review 75:355–67.

Tate, C. Neal, and Roger Handberg. 1991. “Time Binding and Theory Building in Personal Attribute Models of Supreme Court Voting Behavior, 1916–1988.” American Journal of Political Science 35:460–80.

Tribe, Laurence H. 1995. “Text and Structure Seriously: Reflections on Free-Form Method in Constitutional Interpretation.” Harvard Law Review 108 (6): 1221–303.

Tushnet, Mark V. 1985. “A Note on the Revival of Textualism in Constitutional Theory.” Southern California Law Review 58:683–700.

Ulmer, S. Sidney. 1961. “Public Office in the Social Background of Supreme Court Justices.” American Journal of Economics and Sociology 21 (1): 57–68.

———. 1973. “Social Background as an Indicator to the Votes of Supreme Court Justices in Criminal Cases: 1946–1956 Terms.” American Journal of Political Science 17:622–30.

Wagner, Michael W., and Timothy P. Collins. 2014. “Does Ownership Matter? The Case of Rupert Murdoch’s Purchase of the Wall Street Journal.” Journalism in Practice 8 (6): 758–71.

Whittington, Keith E. 1999. Constitutional Interpretation: Textual Meaning, Original Intent, and Judicial Review. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas.

———. 2004. “The New Originalism.” Georgetown Journal of Law and Public Policy 2:599–613.

- Segal-Cover scores are sometimes criticized for being static; meaning, they do not account for changes in justice ideology that may occur over time. Martin-Quinn scores (Martin and Quinn 2002) measure ideology in a way that updates justices’ ideology scores each Court term. Indeed, some justices’ preferences have been shown to evolve (Epstein et al. 2007). ↵

- Three justices—Burton, White, and Vinson—had unknown interpretation styles. The editorials gave no indication of these justices’ interpretation styles, so a final style determination could not be made. Therefore, they are excluded from this table and the statistical analysis. ↵

- Other measures of ideology such as Martin-Quinn scores (Martin and Quinn 2002) use Bayesian statistical methods to update ideology scores over time as new cases are decided. While these scores are useful in some research settings, I choose Segal-Cover scores because they are measured in a similar way as my interpretation variables during the same period of time (prior to the nomination). While Segal-Cover scores are imperfect, they provide a measure of ideology that is methodologically and temporally consistent with my independent variables of interest. ↵

- Since ideology and interpretation style could be related theoretically, collinearity (i.e., the interpretation styles being highly correlated with ideology in a way that affects the results) is possible in this model. Performing the variance inflation factor (VIF) diagnostic on the model provides evidence that collinearity is not an issue. No variable has a VIF over 3, and the average VIF is less than 2. These VIFs are well below the commonly accepted maximum VIF range of 5–10 (Ringle et al. 2015; Hair et al. 2009). ↵