Public Opinion

28 Experimentally Measuring Responsiveness to Criticisms of the US Supreme Court as Antidemocratic

Kyle J. Morgan

In roughly the last ten years, the Supreme Court of the United States has handed down decisions on some of the most controversial social and political questions of the day: from gay marriage and gun control to abortion and affirmative action. Furthermore, in recent years the Court has not been a consistent friend nor foe to either the right or left, making decisions each term that both sides alternately praise or condemn. It is therefore surprising that according to public opinion surveys the US Supreme Court has consistently been rated as the most trusted branch of government. The Supreme Court in this regard is interesting, with the decisions that it hands down appearing not to affect the Court’s core public support.

When talking about the Court, support takes on two different meanings. First there is specific support or agreement with the current behavior of the Court and its decisions. This specific support has been found to mirror the level of agreement or disagreement with recent Court decisions, but it is also fleeting and has been found to be disconnected from the broader support for the Court as an institution (Gibson and Nelson 2014, 2015; but see Bartels and Johnston 2013). Of more interest is the second kind of support, the Court’s diffuse support or legitimacy, which has been defined as “a psychological property of an authority, institution, or social arrangement that leads those connected to it to believe that it is appropriate, proper, and just” (Tyler 2006, 357). When speaking about the Court, this has been conceptualized as “institutional loyalty” or a resistance to making fundamental changes to the way in which an institution operates or functions (Gibson et al. 2003a).[1]

Since the Court’s decisions do not appear to influence its legitimacy in the eyes of the public, where does this legitimacy come from? Gibson (2007) argues that the Court’s legitimacy stems from a belief in core democratic values and beliefs as well as exposure to symbols and messages that present the Court as “different” from normal politics. However, there has also been considerable hand-wringing over the concern that the Supreme Court and its power of judicial review are potentially antidemocratic; this is often called the “countermajoritarian difficulty.” This project uses an experiment to explore the potential for public attitudes toward the Court to be influenced by messages highlighting the Court’s potentially antidemocratic behavior and functions.

While this is an exploratory study, it does provide critical new insights into several scholarly questions. First and foremost, this provides empirical evidence to advance the scholarly debate over whether judicial review is compatible with a democratic system of government. There has been limited scholarly attention to what those who are potentially thwarted by judicial review think about this countermajoritarian difficulty. If we want to further the discussion over judicial review’s democratic credentials, we should be aware of what the public thinks.

Second, there has been a robust scholarly debate over judicial legitimacy, with much of the research finding that the Court’s legitimacy is not impacted by specific decisions. This project takes this analysis in a new direction and explores the extent to which the public’s perceptions of the Court’s legitimacy can be influenced by the language used by elected officials when they discuss the Court. The language used in the experiment differs from previous studies that have focused on specific decisions and instead uses criticisms that raise more fundamental concerns about the role of the Court.

The study will proceed as follows: First, I provide an overview of the existing literature around judicial legitimacy and public attitudes toward the Court more generally. I also provide a brief overview of the debates around the compatibility of judicial review with democracy, and how this relates to the discussion of the Court’s legitimacy. Next, I introduce the methodology and discuss the specifics of the experimental design. This is followed by the analysis, and last, I conclude by situating these results into the larger literature around judicial legitimacy and offering suggestions for future research and consideration.

Judicial Support, Legitimacy, and Public Opinion

Using a variety of public opinion surveys, Gibson and his coauthors have found little evidence that disagreement with specific policies or decisions, also known as specific support, influences attitudes toward the Court’s legitimacy, also known as its diffuse support. The finding, that there is a disconnect between specific and diffuse support, seems surprising as we would expect voters to evaluate the Court based on the decisions it hands down.[2] If that is not the case, then the next logical question is why.

Gibson and Calderia (2009) proposed the “positivity bias” as an explanation of why the Court retains public support in the wake of decisions that voters may disagree with. They argue that through exposure to the Court—for example, when watching coverage of a recent decision—voters are exposed to “symbols of judicial legitimacy.” These symbols include the robes, bench, and the imposing marble “temple” that is home to the Supreme Court, all of which help to retain public support for the Court by highlighting the idea that the Court is different from regular politics (Gibson et al. 2014). Further, there is an existing set of ideas that come from early political socialization that help to reinforce judicial legitimacy (Gibson and Caldeira 2009).[3] These symbols and early political socialization together help to generate what has been referred to as a “reservoir of good will.” Gibson and Caldeira argue that this reservoir is what allows the Court to survive the potential backlash that may come from unpopular decisions. Further, exposure to these symbols can also refill the reservoir of good will by reminding those exposed that the Court is legitimate and “different” from regular politics.

One of the most dramatic examples of this concept would be the 2000 election and the Supreme Court’s decision in Bush v. Gore. For those too young to remember, on election night 2000 the outcome of the election hinged upon Florida. The winner of the state, which was too close to call at the time, would receive the state’s 25 electoral votes, pushing them above the 270 electoral vote requirement and securing the election for either George W. Bush or Albert Gore. However, the margin separating the two candidates in Florida was so close that it triggered a mandatory recount. During this recount, the issue emerged of how to count so-called hanging chads. At the time, paper ballots in Florida used a punch system where a stylus was used to poke out a small circle of paper that was slightly perforated. If one didn’t punch out the circle completely, the circle of paper or “chad” would remain attached. The debate centered on what to do about a chad that was still attached by one or two perforations (aka hanging).[4] Various Florida counties were making different decisions on how to count these votes and there were concerns that the votes were not being counted fairly or equally across the state. These concerns lead to multiple lawsuits challenging the vote-counting procedures. After rulings by the State Circuit Court and the Florida Supreme Court, one of these cases made its way to the US Supreme Court.

The Court, by a 5–4 margin, ruled that the state should stop its recount, and in effect awarded the state of Florida, and by extension the Presidency, to George W. Bush. This 5–4 decision, where the five Republican-appointed justices ruled for the Republican presidential candidate, was criticized by many, but as Gibson, Caldeira, and Spence (2003a) show, disapproval of the decision had little if any impact on the Court’s perceived legitimacy. This raises the question again of what might shape the Court’s legitimacy. If an arguably partisan decision where the Court, in effect, awarded the presidency to the candidate who lost the popular vote (Law 2019; Mann 2001) does not influence the Court’s legitimacy, what does?

While there is considerable evidence that the Court has a sizeable reservoir of good will, “that reservoir is far from bottomless” (Gibson and Nelson 2014, 205). Bartels and Johnston (2013) find that when subjects place themselves on the standard five-point ideological spectrum[5] and then place the Court on the same spectrum, those with the highest level of ideological disagreement between where they placed themselves and where they placed the Supreme Court[6] view the Court as less legitimate. Furthermore, Bartels and Johnston (2012) also find that much of the public views the Court as a political institution. While this may not be surprising to some, it is nonetheless significant in terms of understanding how the public thinks about the Supreme Court. Nicholson and Hansford (2014) as well as Christenson and Glick (2014) find that among the public this perception of the Court and its decisions as political rather than legal has an impact on both the acceptance of decisions and the Court’s overall legitimacy. Taken together, these results and others suggest that the way the Court is talked about, or framed, matters for how the public conceptualizes and, in turn, evaluates the Court.

Framing the Court

“Framing is the process by which respondents develop a conceptualization of an issue or reorient their thinking about an issue based on what considerations are brought to mind.… A frame—whether captured by a single word within the question or by multiple words or phrases—acts as an interpretive lens, provoking a different set of considerations depending on the perspective it portrays” (Koning 2020, 17). The idea that the way the Court is discussed and what related themes are made salient, or how the Court is framed, matters is obvious.

Compared to other institutions, the Court practically invites framing of it and its decisions by other political actors. The Supreme Court is passive and opaque. While other political actors seek out questions and controversies, the Court involves itself only in issues that are brought before it, and even then it selects only a small fraction of those.[7] If Congress is debating salient legislation there is no end to the soundbites and media appearances of elected officials; they are on every screen and in every speaker, spinning the debate and the legislation. Compare that to the Supreme Court at the end of every term. Not only do the justices not appear on the nightly news to discuss the decisions,[8] but the decisions are written in a language most voters do not understand, and arguably few even within the legal community read in their entirety (Chemerinsky 2015).[9] As a result, the decisions and behavior of the Court require translation and communication to the public. Never ones to miss an opportunity, political elites use these moments to spin and frame the Court and its decisions (Morgan and Peabody 2014; Peabody and Morgan 2013). It is in this framing that we can see how the public’s perceptions of the Supreme Court may be shaped.

Building on the vast framing literature,[10] several scholars have found significant framing effects around the Court. For example, Baird and Gangl (2006) find experimental evidence that when a Court decision is framed as political, rather than legal, subjects evaluate the Court and its decision more negatively. Zilis (2015) finds first that the presence of dissenting opinions leads to an increase in the media coverage framing the decision as a conflict or fight. Second, he finds experimental evidence that when the Court’s decisions are framed as such, there is a negative impact on evaluations of the decision, which has the potential to harm the Court’s legitimacy.[11]

The Supreme Court and Judicial Review in American Democracy

While the public, overall, appears to be quite supportive of the Supreme Court, there are some who raise questions concerning the compatibility of the Court with democracy. This debate often hinges upon the Supreme Court’s power of judicial review.[12] Bickel (1962) coins the term “the countermajoritarian difficulty”[13] to summarize this concern: that the unelected and largely unaccountable Supreme Court uses its power of judicial review to invalidate legislation which can potentially undermine the preferences of the majority. The counter-majoritarian difficulty has become what some call the “central obsession” of constitutional scholars (Friedman 2002). While the nuances of this debate are beyond the scope of this chapter, there are some important aspects of this debate that need to be explored so as to provide a basis for the experiment to come.

The first question is, Does the Court in fact behave in a counter-majoritarian fashion? It makes sense to see if in fact the concerns about the Court invalidating the will of “the people” has an empirical basis. Dahl’s (1957) analysis showed that rather than the Supreme Court overruling the national majority or elected officials, more often than not it was frequently in line with both. In turn, this led Dahl to conclude that “the Supreme Court is inevitably part of the dominant national alliance” (1957, 293). While Dahl found that at the national level the Supreme Court did not invalidate the preferences of Congress, Casper (1976), by expanding Dahl’s methodology and scope to include state and local laws being overturned by the Supreme Court, found that the Court did in fact behave in a counter-majoritarian fashion.[14] More recently, Kastellec (2017) complicated this debate. Specifically, he analyzes the legalization of marriage equality after the 2015 decision in Obergefell v. Hodges[15] and finds that by striking down some state-level bans, the Court was behaving in a “promajoritarian” fashion by bringing policy more in line with majority opinion which favored marriage equality. However, that same decision in other states was “counter-majoritarian” where a majority of voters in those states did not support marriage equality.[16]

Persily, Citrin, and Egan (2008) take a variety of policy questions and look at the longitudinal trend of Supreme Court decisions and related public opinion. While on some issues, such as school desegregation, public opinion has moved more in line with the Court’s decision, on other issues like flag burning and school prayer “strong majorities continue to support a position contrary to that of the Court” (Persily et al. 2008, 12).[17] Mishler and Sheehan (1993) similarly find a long history of the Court tending to be in line with the long-term trends in public opinion, but in more recent years the Court has remained to the right of where the public has been.[18] (See also the Johnson and Strother chapter in this volume.) Thus in answering the question of whether the Court is a countermajoritarian institution, the evidence suggests that it can be at times. However, the extent that voters are troubled by this remains an open question.

What do those who are potentially “countered” by the Supreme Court’s use of judicial review think about the role of the Court? While scholars may have debated and studied these issues for decades, we know surprisingly little about what regular voters think of these different debates and concerns (see Bickel 1962; Ely 1980; and even Federalist, no. 78). By better understanding the public’s attitudes toward judicial review—a public whose preferences are potentially thwarted by the Court’s use of it—we can further refine our understanding of public attitudes toward the judiciary. Also, we can improve our normative conceptions of how the Supreme Court and judicial review should, or should not, fit into our political system. If, potentially, the public is ambivalent or even welcoming of judicial review, this has the potential to alter how we view the concerns around the counter-majoritarian dilemma.

Methods

In order to investigate these questions surrounding public opinion and judicial legitimacy, I fielded a survey experiment that employs vignettes regarding the Court (May 28 through June 2, 2019) and uses a nonprobability convenience sample.[19] As seen in table 1 below, though this sample is not nationally representative, it does compare well to national demographics and the American National Elections Survey (ANES), a nationally representative survey fielded biannually.

| Percent of sample | US Census* | ANES** | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender

Male Female Other |

--

47.4 52.4 .2 |

--

49.2 50.8 |

--

46 52 .2 |

| Race

Non-white White (non-Hisp.) |

--

39 61 |

--

39.3 60.7 |

--

28 71 |

| Age

18-24 25-34 35-49 50-64 65+ |

--

11.9 19 26.5 27.1 15.5 |

--

9 14 19 19 16 |

--

7.6 16.6 23.3 27.3 22.3 |

| Party ID

Rep Ind. Dem |

--

37 17.2 45.8 |

-- | --

40.53*** 13.5 45.4 |

| Ideology

Lib Con In btwn. |

--

28.7 35.1 36.3 |

-- | --

24.1 32.2 20.94**** |

Table 1: Demographic characteristics of the experiment sample compared to US Census and 2016 American National Election Time Series

* Gender and race: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045218; Age: https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=PEP_2017_PEPSYASEXN&prodType=table.Note:age percentages here do not include 0–17.

** ANES 2016 time series.

*** Collapsed version of ANES 7-point party identification question.

**** Collapsed version of ANES 7-point ideology question.

In the study of courts and judicial legitimacy, I follow in a long line of experimental work, dating back almost twenty years (B. L. Bartels 2014).[20] Specifically, the use of vignettes as part of the experimental design, as used here, is common in the judicial legitimacy literature (Baird and Gangl 2006; Christenson and Glick 2014; Zilis 2015). Vignettes as a design involve presenting subjects with one or more passages of text to read and then measuring their response after reading the text(s). Vignettes can be thought of as the “treatment”; by exposing (or treating) the subjects with different vignettes, we can compare our dependent variables based on the different treatment groups. For example, an experiment may present a vignette discussing a policy proposal, but half the subjects are randomly assigned a treatment where they are told the policy proposal is coming from a Congresswoman while the second half is randomly assigned to a treatment where the same proposal is attributed to a Congressman. After reading the passage you then measure agreement with the passage and see if, for example, there is a difference between those in the Congresswoman treatment and those in the Congressman treatment. If the only difference between the treatment vignettes is the gender of the person presenting the proposal, and we detect a difference between the groups, we can say that the gender cue influenced how subjects evaluated the passage.

| Political | Countermajoritarian | Democratic process | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Democrat | |||

| Republican | |||

| Bipartisan |

Table 2: Experimental design

This experiment used a 3 × 3 design (see table 2), where 1,004 subjects were randomly assigned to one of nine treatments where they read a passage from either a Republican, Democratic, or bipartisan group of Senators and members of the House criticizing the judiciary in one of three different ways.

Using the language found in an analysis of congressional press releases as a guide (Morgan 2020), I crafted three different criticism types that reflect three different ways of criticizing the Court; political, countermajoritarian, or democratic process. For the “political” criticisms, the main idea here is simply that the Court is making “bad” decisions, not interpreting the Constitution correctly, and the vignette, overall, attacks the decision-making process.

Political frame:

In a recent speech, [a bipartisan group of Senators and members of the House of Representatives / a group of Republican Senators and members of the House of Representatives / a group of Democratic Senators and members of the House of Representatives] discussed the role of the Supreme Court. The [bipartisan group of Senators and members of the House of Representatives / group of Republican Senators and members of the House of Representatives / group of Democratic Senators and members of the House of Representatives] criticized the Court saying that; “The Supreme Court continues to make the wrong decisions. This is not about ideological disagreement, instead the Court simply continues to read and apply the constitution incorrectly. Instead of making decisions based on the text of the constitution and legal precedent the Justices make decisions based on their own political preferences. We are deeply concerned about the future of our country if we continue to allow the Supreme Court to substitute the political ideology of the justices for sound legal reasoning. As a nation founded on Constitutional principles and the rule of law, we urge all Americans to question why we allow the Supreme Court to continue to undermine that.”

The “countermajoritarian” criticisms focus on the idea that the Court’s decisions are thwarting the will of the people and/or voters. Finally, the “democratic process” criticisms present the idea that the Court’s decisions are harming access to and participation in the democratic process. This line of criticism draws upon the work of Ely (1980), but rather than viewing judicial review as justifiable when it defends democracy and democratic participation, it turns this into a criticism by attacking the Court for undermining those concepts. Additionally, while previous studies have analyzed the harm that disagreeable decisions may or may not have on support for the Court, the democratic process and countermajoritarian criticisms offer something new by shifting the focus from a disagreeable decision to attacking the Court as incompatible, or inconsistent, with democracy.

Countermajoritarian frame:

In a recent speech, [a bipartisan group of Senators and members of the House of Representatives / a group of Republican Senators and members of the House of Representatives / a group of Democratic Senators and members of the House of Representatives] discussed the role of the Supreme Court. The [bipartisan group of Senators and members of the House of Representatives / group of Republican Senators and members of the House of Representatives / group of Democratic Senators and members of the House of Representatives] criticized the Court saying that; “The Supreme Court continues to make decisions that are opposed to the wishes of voters. In a democracy it should not be allowed that nine unelected, and unaccountable, judges are able to make decisions that contradict the will of the people. It should be through the political process, where voters decide what is best for them, and in turn elect representatives to carry out those wishes. We, the elected representatives, and the voters should resolve these issues, and not turn that over to judges to make those decisions behind closed doors. The Supreme Court is not only making the wrong decisions, but by ignoring and invalidating the will of the people, it is undermining our democratic form of government.”

Democratic process frame:

In a recent speech, [a bipartisan group of Senators and members of the House of Representatives / a group of Republican Senators and members of the House of Representatives / a group of Democratic Senators and members of the House of Representatives] discussed the role of the Supreme Court. The [bipartisan group of Senators and members of the House of Representatives / group of Republican Senators and members of the House of Representatives / group of Democratic Senators and members of the House of Representatives] criticized the Court saying that; “The Supreme Court continues to make decisions that weaken the ability of the voters to have a voice in government and politics. All voters should be troubled by a Court that allows special interests to drown out the voice of voters. In a democracy it should be the voters, not special interests, who elected officials pay attention to. The Supreme Court should be making decisions that encourage voting and participation in our political process, instead it continues to rule against these core democratic values. We should encourage all citizens to have a voice and to exercise their right to vote, but the Supreme Court appears opposed to allowing voters to exercise these most fundamental rights.”[21]

To make the criticisms believable, the language of the criticisms is negative, but generic enough so that it could be reasonably be attributed to any of the sources. This means that the criticisms do not mention specific decisions or ideological positions. For example, it would be hard to believe a criticism of the Citizens United[22] (2010) decision or the Court being too conservative would come from a Republican or that a criticism of Obergefell or the Court being too liberal would come from a Democrat.

After reading the passage, subjects are then given two sets of questions that serve as the dependent variables in analysis. In the first set, subjects are asked about their agreement with the statement itself, how strong they felt the argument was, a measure of hypothetical willingness to donate to a candidate or group advocating for what the passage discussed, and how credible those quoted were. These variables represent a basic reaction to the passage or, in the case of willingness to donate, a different way to conceptualize agreement with the passage. If we are to uncover evidence that the frames had an effect, we should find evidence of that here. These items also allow us to see how voters view these different messages. Since the public views the Court highly, we first need to see if they are even open to messages calling into question the very role of the Court. If voters do not reject these criticisms, we can then take this analysis one step further and see what influence they have on evaluations of judicial legitimacy.

The second set of dependent variables, listed below, consists of standard measures of judicial legitimacy developed by Gibson and Nelson (2014).[23] Subjects were asked the following questions at the beginning of the survey and then again after receiving the treatment, which allowed me to measure any potential change between the initial attitudes and those after the treatment. Finding an effect here would offer important new information to the debate over judicial legitimacy.

-

“It is inevitable that the US Supreme Court gets mixed up in politics; therefore we ought to have a stronger means of controlling the actions of the US Supreme Court.”

-

“The US Supreme Court ought to be made less independent so it listens a lot more to what the people want.”

-

“Judges on the US Supreme Court who consistently make decisions at odds with what a majority of the people want should be removed from their position as judges.”

-

“If the US Supreme Court started making a lot of decisions that most people disagree with, it might be better to do away with the Supreme Court altogether.”

-

“The right of the Supreme Court to decide certain types of controversial issues should be reduced.”

-

“The US Supreme Court gets too mixed up in politics.”

The experiment also ensured that subjects paid attention through two manipulation checks. Subjects were asked “who was quoted in the article you just read” and “True or false, the passage you just read praised the Supreme Court.” Seventy-nine percent of the subjects got both manipulation checks correct. Manipulation checks allow us to ensure a subject was paying attention and properly perceived the treatment. The analysis below uses only those subjects who correctly answered at least one of the manipulation checks.

Hypotheses

I am interested in public attitudes toward the three criticism frames—countermajoritarian, democratic process, and political—and further, if they present a threat to judicial legitimacy. However, given ample evidence around the influence of partisanship on voters’ attitudes, and that the partisan source cue was manipulated in the experiment, I propose the following initial hypothesis.

Based on existing research on framing and partisanship in regard to support for the Supreme Court (Clark and Kastellec 2015), and the current level of hyperpartisanship among the American electorate (Mason 2018), I expect that subjects will respond more favorably to a criticism that is from their copartisans, regardless of the frame used. Therefore, even though analysis of congressional language found differences between how Democratic and Republican legislators discussed the Court (Morgan 2020), as with much of today’s politics, I expect that partisanship will be a driving factor here.

However, even if partisanship is a significant force, we can look within the partisanship manipulations, in effect controlling for the influence of partisanship, to explore the responsiveness to the different frames. Based on the language used by legislators in press releases, Democratic legislators overwhelmingly preferred democratic process language while the Republican peers preferred countermajoritarian language (Morgan 2020). Therefore, I expect that subjects, when presented with a copartisan source—for example, a Republican getting a message from a fellow Republican—will evaluate statements that are consistent with how their party discussed the Court more positively compared to those framed in the opposite ways. This leads me then to the following two hypotheses:

I am also interested in how these types of criticisms affect judicial legitimacy. Scholars have grappled with the Court’s democratic credentials as a theoretical issue for decades, but there has been little systematic analysis of the extent to which the public is responsive and/or concerned about these issues.[24] Therefore, I propose two hypotheses based on the experimental manipulations:

The logic here is that attacks on the democratic compatibility of the Court will harm the Court’s legitimacy only when that attack comes from a copartisan. Alternatively, H3b is what I am calling the “roughing the ref hypothesis.” When the more substantial criticisms come from a counterpartisan, I expect there to be a backlash in which partisans react to the other party’s attack by coming to a defense of the Court’s legitimacy.

Analysis

H1 claims that subjects will respond to the source cue of the criticism, rather than the frame used. Since “partisanship is a hell of a drug,” the expectation is that subjects’ first reaction to the statements will be contingent on the partisanship of the source cue. This does not mean that the message does not matter; rather, that I expect the criticism frame to come into play when the message comes from a copartisan source. For this analysis then I have run several two-way between-subjects analysis of variance tests (ANOVAs), which test if the difference between independent groups is statistically significant for Democrats and Republicans separately looking at the effects of the source cue and criticism frame on the four dependent variables.

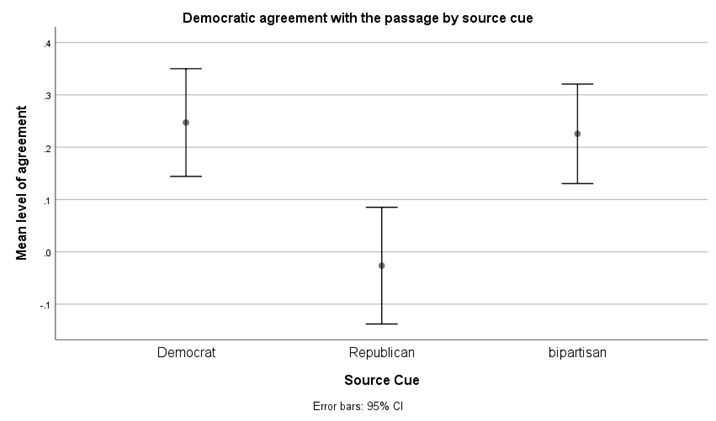

For Democrats, there is a statistically significant effect for the source cue and the criticism frame when it comes to their level of agreement with the passage.[25] The Tukey HSD post hoc test showed statistically significant differences between the Republican source cue and the Democratic (p = .001) and bipartisan (p = .001) source cues (see figure 1 below), as shown in figure 1 below, where the bars for Democratic and bipartisan groups do not overlap with the Republican line. There was no statistically significant difference between the Democratic and bipartisan source cues (p = .997), shown in the figure below where these two bars overlap.

For the criticism frames, Democrats agreed more with the democratic process frame compared to the countermajoritarian frame by .199 (p = .02). The post hoc analysis did not show any other comparisons between the frames as statistically significant.

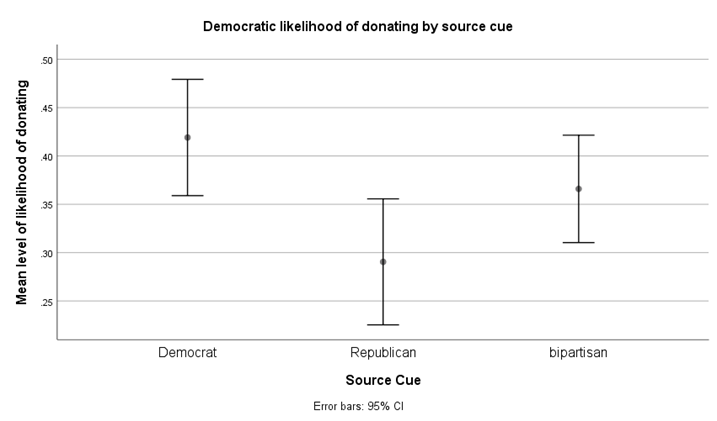

When we look at how likely Democrats would be to donate, we see a statistically significant difference based on the source cue,[26] but not for the criticism type. The Tukey HSD post hoc test showed that in terms of donating, the statistically significant difference, as seen in figure 2 below, was between the Democratic and Republican source cues (p = .019). The other comparisons were not statistically significant. Similarly, when it comes to evaluation of the passage’s strength, there is a similar statistically significant difference based on the source cue,[27] but not for the criticism frame.

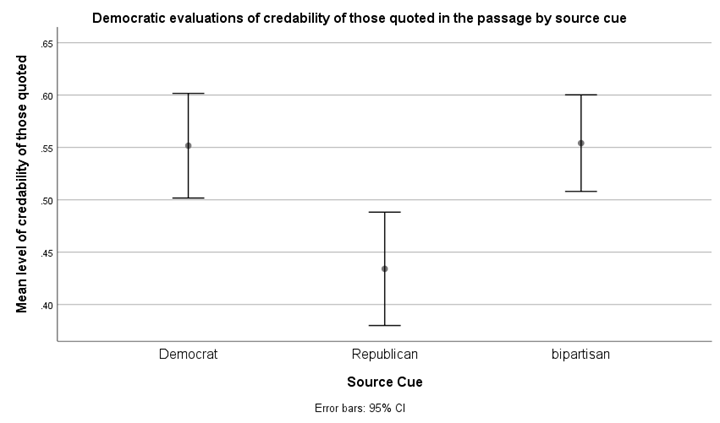

Finally, for the credibility afforded to those quoted in the passage, among Democrats I find another statistically significant difference based on the source cue,[28] but not for the criticism frame. The post hoc analysis showed that Republican passages had a mean evaluation .113 less than those attributed to only Democrats (p = .006), and .122 less than those attributed to both Democrats and Republicans in the bipartisan treatment (p = .002).

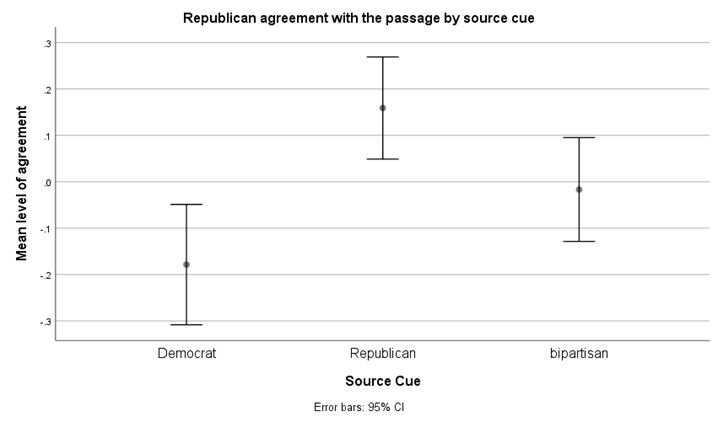

Moving now to Republicans, I find an even stronger effect of partisanship in terms of their level of agreement with the passage. The difference between evaluations was statistically significant based on the source cue,[29] but not for the different criticism types (p = .055). The Tukey HSD post hoc test showed that Republican subjects evaluated passages attributed to Democrats compared to those from Republicans worse by .344, or roughly 1/3rd of the scale (p < .001). The other comparisons were not statistically significant.

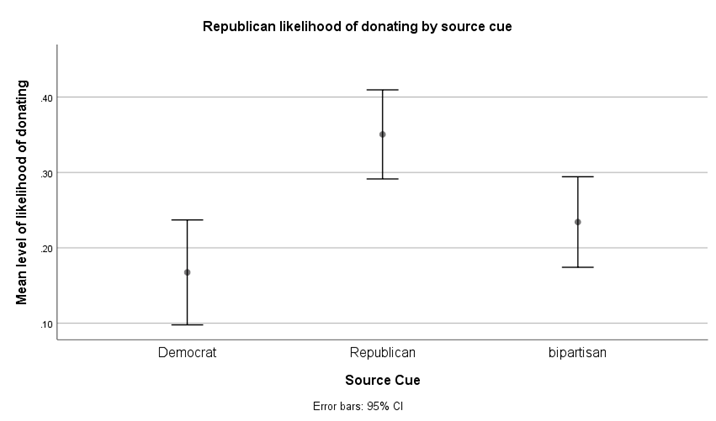

When we move to Republican’s likelihood of donating, the model Levene’s Test was statistically significant (>.05), violating the assumption of homogeneity of variance. Since this is the case, I proceed with some level of caution and will look for a significance level of < .01, rather than the normal < .05 level. Even with this higher bar, I find that there is a statistically significant effect of the source cue on Republicans’ likelihood of donating[30] (see figure 5), but the differences between the criticism frames were not statistically significant. The Tukey HSD post hoc tests showed Republican subjects were more willing to donate when the criticism came from a fellow Republican compared to a Democrat (p < .001) or even when it came from a bipartisan group (p = .018).

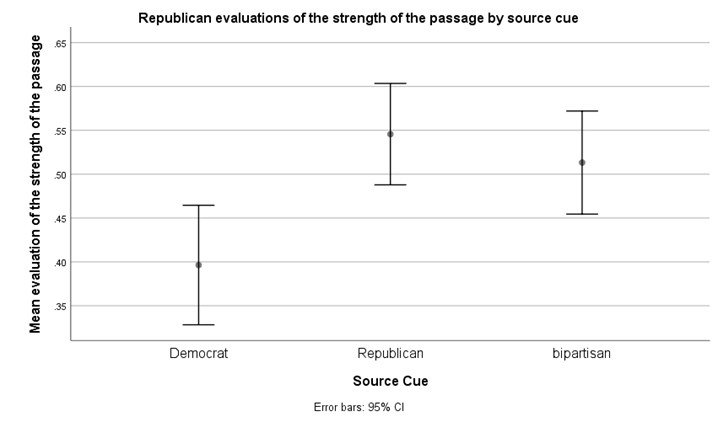

Turning to how strong Republicans viewed the passage to be, I find a statistically significant difference here as well, based on the source cue.[31] Republicans appear to punish those passages that do not include copartisans (see figure 6). Using the Tukey HSD post hoc test, compared to a Republican source cue, those that came from Democrats were evaluated as worse by .157 (p = .002). Also, when compared to a bipartisan source cue, Democratic statements received a lower rating by .123 (p = .019). There was not a statistically significant difference between the Republican and bipartisan statements (p = .7).

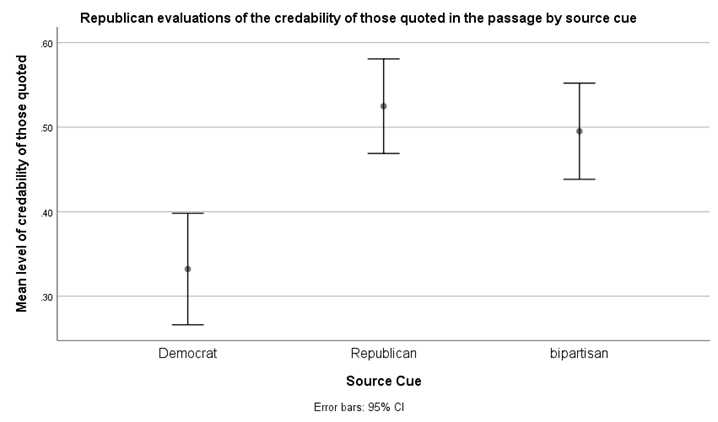

Finally, Republicans appear to evaluate the credibility of those quoted in the passage based on the partisanship of the messagexxxii (see figure 7), while the criticism type was not statistically significant. Similar to how they evaluated the strength of the passage, Republicans appear to punish press releases that do not include fellow Republicans, with those coming from Democrats being evaluated as worse by –0.19 compared to a Republican source cue (p < .001), and Democratic passages were evaluated as worse than the bipartisan treatment by –0.159 (p = .001), based on the Tukey HSD post hoc test. There was not a statistically significant difference between the Republican and bipartisan source cues (p = 1.0).

For the first hypothesis, the evidence supports it. Both Democrats and Republicans look as if they are first and foremost concerned about the partisanship of those quoted in the passage. Across the board, I find that partisans evaluate the passage as more credible, view it as stronger, are more likely to donate, and generally agree more with passages that come from copartisans.[32] This, though, does not mean that the frames do not matter. It means rather that we need to remove the partisan influence by looking at the influence of the criticism frames within copartisan treatments.

H2a and H2b are two sides of the same coin. The idea here is that since partisanship is such a significant factor, we need to control for its influence and look at how partisans respond to a copartisan frame. This analysis proceeds using one-way ANOVA and focusing on partisans who received a copartisan frame.

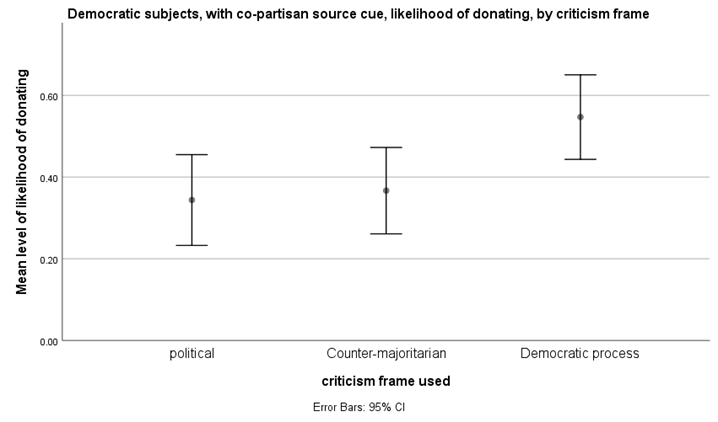

Beginning with Democratic subjects who were told the criticism came from fellow Democrats, in terms of agreement with the passage I find that the differences between the criticism types were not statistically significant (p = .057). However, in terms of their willingness to donate, Democrats appear to respond to the criticism frame presented, as the difference between the criticism type is statistically significant.[33] The Tukey HSD post hoc test shows that the statistically significant difference is between the democratic process and political frames (p = .031), with Democrats being .20 points more likely to donate when presented with a democratic process frame compared to the political frame (see figure 8). The difference between the countermajoritarian and democratic process frames was not statistical significance (p = .055). Remember, the results here are Democrats being asked about donating to fellow Democrats, and therefore the difference detected here appears to be a result of the language used, and not the partisan source cue.

In terms of evaluations of the strength of the passage (p = .139) and its credibility (p = .453), I find that there is no statistically significant difference between the criticism frames for Democrats who received a copartisan source cue.

In the end, then, this analysis suggests limited evidence for H2a that Democratic subjects responded to the criticism frames presented to them. Even when we remove the influence of partisanship, there is no evidence that Democrats agreed more with the democratic process frame compared to the countermajoritarian one, and only slight evidence that they were more willing to donate when exposed to the democratic process frame compared to the political one. This offers some limited evidence in support of the hypothesis.

For Republicans, I find even less evidence that the criticism frame influenced their attitudes toward the passage. There was no statistically significant difference between the frames in terms of agreement with the passage (p = .575), willingness to donate (p = .490), how strong the argument in the passage was (p = .538), nor for how credible those quoted in the passage were (p = .918). Therefore, for H2b, I find no evidence that Republicans responded to the criticism frames they were presented with.

H3a looks at the influence the frames may have on evaluations of the Court’s legitimacy. Previous research has found that framing the Court in a way other than “legal” has the potential to affect how legitimate voters view it to be (Baird and Gangl 2006; B. L. Bartels and Johnston 2012; Nicholson and Hansford 2014). H3a takes this line of inquiry in a different direction by asking if framing the Court as harmful to democracy harms evaluations of its legitimacy. To the extent that the democratic process and countermajoritarian frames call into question the Court’s legitimacy in a way that the political criticisms do not, I hypothesize that these frames will diminish the Court’s legitimacy.

For this analysis I shift my approach to use a two-way repeated measures ANOVA, taking advantage of the fact that the same legitimacy questions were asked of all subjects at the beginning of the survey and after the treatments. Repeated measures ANOVA has the benefit of controlling for the effect of how legitimate voters viewed the Court at the start of the survey, prior to any of the treatments, allowing one to more effectively detect any changes in the posttreatment measures and facilitating a between-subjects analysis (between the groups of different criticism frames) and a within-subjects analysis (comparing individuals’ pre- and posttreatment legitimacy scores).

For Democratic subjects who received a Democratic source cue, I find that there is no statistically significant effect of the criticism frame on evaluations of legitimacy, the within-subjects analysis (p = .453) was not statistically significant, nor was the between-subjects analysis (p = .055). Among Republicans, I also find no evidence that the criticism frames, when paired with a copartisan source cue, had any effect on evaluations of judicial legitimacy. The within-subjects analysis was not statistically significant (p = .735) nor was the between-subjects analysis (.671).

Thus for the hypothesis that these criticism frames would harm the Court’s legitimacy, I find no supporting evidence. While some work has found that framing the Court as political rather than legal may damage the Court’s legitimacy, my analysis does not suggest that highlighting the potentially antidemocratic nature of the Court has a similar effect.

H3b is a flip on the previous hypotheses. Since partisanship is a driving factor in responsiveness to the passages, I expected that when subjects were presented with a counterpartisan framing (i.e., a Democrat presented with a Republican source cue, and vice versa) they might come to the defense of the Court and rate it as more legitimate. In the analysis then I expect that when presented with a counterpartisan frame that calls into question the compatibility of the Court and democracy, subjects will increase their evaluations of how legitimate they view the Court to be.

Using two-way repeated measures ANOVA again I test this hypothesis by looking at both the within-subjects change from the pretreatment scores to the posttreatment scores, and at the effects between subjects caused by the criticism frame they were presented. Looking at Democrats first, I find no evidence that when presented with a counterpartisan frame that they view the Court as more legitimate. Neither the within-subjects analysis (p = .999) nor the between-subjects analysis (p = .531) was statistically significant.

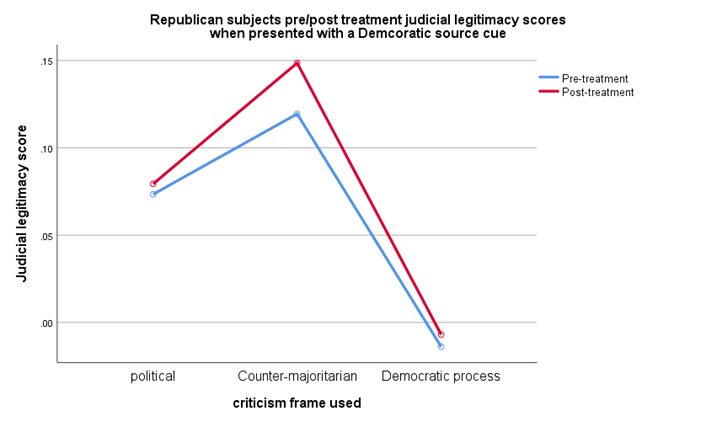

For the Republican subjects, there was not a statistically significant change within subjects when presented with a Democratic attack on the Court (p = .824). However, the between-subjects analysis did show a statistically significant difference between the criticism frames.[34] According to the Bonferroni post hoc test, evaluations of the Court’s legitimacy after the treatment were .144 points lower in the democratic process frame compared to the countermajoritarian frame (p < .05). Additionally, as seen in figure 9 below, Republicans appear to come to the Court’s defense when Democrats use countermajoritarian language. While the differences between the criticism frames and the pretreatment legitimacy scores were not statistically significant (p = .07), this does suggest that potentially there is something about receiving a counterpartisan frame and either the countermajoritarian or democratic process frame that influenced Republican’s attitudes toward the Court.

This suggests Republicans are responsive to these criticisms, and when Democrats “borrow” Republican language to attack the Court, they view this differently than when Democrats attack the Court on their own terms.[35] While the criticisms did not appear to change individual evaluations of the Court, Republicans at least appear to express a distinction between the criticism frames in terms of how legitimate they view the Court to be.

Conclusion

The literature is full of examples that disagreement with specific decisions of the Court does little, if anything, to harm the Court’s legitimacy. Other projects have looked at how the framing of those decisions can influence the public’s support for them, and even the Court’s legitimacy. This study goes in a different direction by analyzing the extent to which framing the Court as antidemocratic can influence attitudes toward’ the Court’s legitimacy. Briefly, my results suggest that while these criticisms do not drain the Court’s reservoir of goodwill or its legitimacy, these antidemocratic frames may be a threat to the Court over the long run.

My analysis finds limited evidence that attacking the Court as antidemocratic does much to harm the Court’s legitimacy. Even when presented with a copartisan source cue, there is no evidence that highlighting the ways in which the Court is incompatible with or harmful to democracy diminishes the Court’s legitimacy. The most interesting finding in this area, however, is that Republican subjects appear to come to the Court’s defense when presented with a Democrat attacking the Court using countermajoritarian language. However, this does not mean that these frames were not salient to subjects.

Once we account for the partisanship of those quoted in the passage, I find evidence that subjects responded to frames in a way that was consistent with the partisan divide in how legislators use those same frames. Specifically, I find that Democrats are more responsive to the democratic process framing, while Republicans prefer the countermajoritarian language. This preference appears to be strongest among Democrats, who express a greater willingness to donate when presented with the democratic process framing. Interestingly, this would imply that for Democratic elected officials, even though the Court is viewed positively by Democrats and the public at large, there is something to be gained by using the Supreme Court as a foil for their criticisms.

For the larger discussion about the role of the Supreme Court in our democracy, I find that voters are open to these messages that the Court is, potentially, antidemocratic. Despite the Court’s high levels of approval and legitimacy, it does not appear that the subjects here rejected these frames. Had subjects evaluated one criticism frame more negatively, that would suggest they disagreed with that messaging. The lack of differences in how subjects evaluated the messaging regarding the Court suggests that the subjects were open to criticisms of the Court, and further that they do not draw much of a distinction regarding how it is done. While these messages did not directly diminish the Court’s legitimacy, the fact that voters did not reject them is an important finding nonetheless.

As the Court continues to involve itself in many of our most salient and controversial social and political questions, we may see these frames invoked more frequently. While a one-off criticism does not appear to diminish the Court’s legitimacy, what remains to be seen is if sustained criticisms of a Court that continues to involve itself in our democratic and political process strike a nerve with voters over time, possibly opening the doors for criticisms of the Court that previously would have been politically unthinkable.

Activity

-

- You have recently been hired by a political consulting firm (congratulations!). Your firm is working with a local member of Congress who is deeply upset with the US Supreme Court. She would like you to work on some messaging to attack the Court that she can use in her upcoming House race.

- Do you advise her to attack the Court or not? (why or why not?)

- How do you suggest that she attack the Court? Why do you think this would be an effective line of attack? If her district is solidly in line with her partisanship, would your advice be different than if it were a more competitive district?

- How would your advice differ if the Congresswoman wants to attack the Court to score political points, versus if her goal is to actually rein in or punish the Court?

- Never one to miss a business opportunity, your firm is also doing some consulting for her opponent. How would you suggest that they respond to the attacks on the Court (if at all)?

- Which type of criticism (political, countermajoritarian, or democratic process) resonates more with you? Why do you find that line of attack more compelling, or alternatively, why are the others less powerful?

- If you were to replicate this experiment, how would you change the treatments (vignettes) used?

- What is the proper role that you see for the Supreme Court in our democracy? What types of cases do you think the Court should be involved in or not involved in? Can you come up with a nonpartisan set of guidelines for how the Court should behave?

- You have recently been hired by a political consulting firm (congratulations!). Your firm is working with a local member of Congress who is deeply upset with the US Supreme Court. She would like you to work on some messaging to attack the Court that she can use in her upcoming House race.

Appendix 1: Significant Correlations between Demographics and Manipulation Checks

In the exploration of the data prior to the analysis, I uncovered a correlation between several of the demographic variables and the manipulation checks. There was a weak positive correlation between age and the combined measure of the manipulation checks (r = .287, n = 991, p < .001). A similarly weak and positive relationship was found between the manipulation checks and education (r = .243, n = 990, p < .001), political knowledge (r = .359, n = 991, p < .001), and self-identified White subjects (r = .212, n = 991, p < .001). There were equally weak and negative correlations between the manipulation checks and self-identified black respondents (r = –0.116, n = 991, p < .001) and Hispanics (r = –0.099, n = 991, p < .01).

While correlations are never ideal, the randomization was carried out successfully and, despite the small correlations reported above, these findings should not complicate the analysis or muddy the results of the experiment.

References

“About the Supreme Court.” n.d. United States Courts. Accessed August 23, 2020. http://www.uscourts.gov/about-federal-courts/educational-resources/about-educational-outreach/activity-resources/about.

Baird, V. A., and A. Gangl. 2006. “Shattering the Myth of Legality: The Impact of the Media’ s Framing of Supreme Court Procedures on Perceptions of Fairness.” Political Psychology 27 (4): 597–614.

Bartels, B. L. 2014. “Experiments in Law and Courts Research: Opportunities, Issues, and Suggestions.” Newsletter of the Law & Courts Section of the American Political Science Association 24 (1): 29.

Bartels, B. L., and C. Johnston. 2013. “On the Ideological Foundations of Supreme Court Legitimacy in the American Public.” American Journal of Political Science 57 (1): 184–99.

Bartels, B. L., and C. D. Johnston. 2012. “Political Justice? Perceptions of Politicization and Public Preferences toward the Supreme Court Appointment Process.” Public Opinion Quarterly 76 (1): 105–16.

Bartels, L. M. 2008. Unequal Democracy: The Political Economy of the New Gilded Age. 1st ed. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Bickel, A. 1962. The Least Dangerous Branch. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Burke, E. 1774. The Works of the Right Honourable Edmund Burke. Project Gutenberg. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/58646/58646-h/58646-h.htm.

Butler, D. M., and D. E. Broockman. 2011. “Do Politicians Racially Discriminate against Constituents? A Field Experiment on State Legislators.” American Journal of Political Science 55 (3): 463–77.

Caldeira, G. A., and J. L. Gibson. 1992. “The Etiology of Public Support for the Supreme Court.” American Journal of Political Science 36 (3): 635–64.

Carroll, S. 2003. “Representing Women.” In Women Transforming Congress, edited by Cindy Simon Rosenthal, 50–68. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Casper, J. 1976. “The Supreme Court and National Policy.” The American Political Science Review 70 (1): 50–63.

Chemerinsky, E. 2015. The Case against The Supreme Court. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin Books.

Chong, D., and J. N. Druckman. 2007. “Framing Theory.” Annual Review of Political Science 10 (1): 103–26.

Christenson, D., and D. Glick. 2014. “Chief Justice Roberts’s Health Care Decision Disrobed: The Microfoundations of the Supreme Court’s Legitimacy.” American Journal of Political Science 59 (2): 403–18.

Clark, T. S., and J. P. Kastellec. 2015. “Source Cues and Public Support for the Supreme Court.” American Politics Research 43 (3), 504–35.

Clifford, S., and J. Jerit. 2014. “Is There a Cost to Convenience? An Experimental Comparison of Data Quality in Laboratory and Online Studies.” Journal of Experimental Political Science 1 (2): 120–31.

Dahl, R. A. 1957. “Decision Making in a Democracy: The Supreme Court as a National Policy Maker.” Journal of Public Law 6 (1): 279–95.

Ditmar, K., K. Sanbonmatsu, and S. Carroll. 2018. A Seat at the Table: Congresswomen’s Perspectives on Why Their Presence Matters. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Domhoff, G. W. 2006. Who Rules America? Power, Politics, and Social Change. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Ely, J. 1980. Democracy and Distrust: A Theory of Judicial Review. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Franklin, C., and L. Kosaki. 1989. “Republican Schoolmaster: The US Supreme Court, Public Opinion, and Abortion.” American Political Science Review 83 (3): 751–71.

Friedman, B. 2002. “The Birth of an Academic Obsession: The History of the Countermajoritarian Difficulty, Part Five.” Yale Law Journal 112:153–259.

Gibson, J. L. 2007. “The Legitimacy of the Supreme Court in a Polarized Polity.” Journal of Empirical Legal Studies 4 (3): 507–38.

Gibson, J. L., and G. A. Caldeira. 2009. Citizens, Courts, and Confirmations: Positivity Theory and the Judgments of the American People. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Gibson, J. L., G. A. Caldeira, and L. K. Spence. 2003a. “Measuring Attitudes toward the United States Supreme Court.” American Journal of Political Science 47 (2): 354–67.

———. 2003b. “The Supreme Court and the US Presidential Election of 2000: Wounds, Self-Inflicted or Otherwise?” British Journal of Political Science 33 (4): 535–56.

Gibson, J. L., M. Lodge, and B. Woodson. 2014. “Losing, but Accepting: Legitimacy, Positivity Theory, and the Symbols of Judicial Authority.” Law & Society Review 48 (4): 837–67.

Gibson, J. L., and M. J. Nelson. 2014. “The Legitimacy of the US Supreme Court: Conventional Wisdoms and Recent Challenges Thereto.” Annual Review of Law and Social Science 10:201–19.

———. 2015. “Is the US Supreme Court’s Legitimacy Grounded in Performance Satisfaction and Ideology?” American Journal of Political Science 59 (1): 162–74.

Hamilton, A., J. Madison, and J. Jay. (1790) 2003. Federalist, no. 78. In The Federalist Papers, 1st ed., edited by C. Rossiter. New York: Signet.

Hasen, R. L. 2016. Celebrity Justice: Supreme Court Edition. UC Irvine School of Law. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2611729.

Hoekstra, V. J. 2000. The Supreme Court and Local Public Opinion. American Political Science Review, 94 (1), 89–100.

Kastellec, J. P. 2017. “Judicial Federalism and Representation.” Journal of Law and Courts 6 (1): 51–92.

Koning, A. 2020. A Survey Researcher’s Many Decisions. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Law, T. 2019. “These Presidents Won the Electoral College—but Not the Popular Vote.” TIME, May 15, 2019. https://time.com/5579161/presidents-elected-electoral-college/.

Mann, T. E. 2001. “Reflections on the 2000 US Presidential Election.” Brookings, January 1, 2001. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/reflections-on-the-2000-u-s-presidential-election/.

Mason, L. 2018. Uncivil Agreement: How Politics Became Our Identity. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Minta, M. D., and V. Sinclair-Chapman. 2012. “Diversity in Political Institutions and Congressional Responsiveness to Minority Interests.” Political Research Quarterly 66 (1): 127–40.

Mishler, W., and R. Sheehan. 1993. “The Supreme Court as a Countermajoritarian Institution? The Impact of Public Opinion on Supreme Court Decisions.” American Political Science Review 87 (1): 87–101.

Mondak, J. J. 1992. “Institutional Legitimacy, Policy Legitimacy, and the Supreme Court.” American Politics Quarterly 20 (4): 457–77.

Morgan, K. J. 2020. “Is Anyone Worried about Judicial Review: Attitudes towards Judicial Review in an Era of Political Turmoil.” PhD diss., Rutgers University. https://doi.org/doi:10.7282/t3-mzvc-f935.

Morgan, K. J., and B. G. Peabody. 2014. “What We Talk about When We Talk about Courts: Congressional Websites and Changing Attitudes toward the Judiciary, 2009–2014.” British Journal of American Legal Studies 3 (1): 335–66.

Morgan, K. J., and W. J. Young. 2019. “What Counter-Majoritarian Dilemma? Experimentally Evaluating Citizen’s Views of the Democratic Nature of the Supreme Court.” Constitutional Studies 5:1–30.

Mullinix, K. J., T. J. Leeper, J. N. Druckman, and J. Freese. (2015). “The Generalizability of Survey Experiments.” Journal of Experimental Political Science 2 (2): 109–38.

Nelson, M. J., and J. L. Gibson. 2019. “How Does Hyper-politicized Rhetoric Affect the U.S. Supreme Court’s Legitimacy?” Journal of Politics 81 (4): 1512–16. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/704701.

Nicholson, S. P., and T. G. Hansford. 2014. “Partisans in Robes: Party Cues and Public Acceptance of Supreme Court Decisions.” American Journal of Political Science 58 (3): 620–36.

Nicholson, S. P., and R. Howard. (2003). “Framing Support for the Supreme Court in the Aftermath of Bush v. Gore.” Journal of Politics 65 (3): 676–95.

Peabody, B. G., and K. J. Morgan. 2013. “Hope, Fear and Loathing, and the Post-Sebelius Disequilibrium: Assessing the Relationship between Parties, Congress, and Courts in Tea Party America.” British Journal of American Legal Studies 2 (1): 27–58.

Persily, N., J. Citrin, and P. Egan, eds. 2008. Public Opinion and Constitutional Controversy. 1st ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rosenthal, C. S. 1998. When Women Lead: Integrative Leadership in State Legislatures. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schattschneider, E. 1960. The Semisovereign People: A Realist’s View of Democracy in America. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

Seltzer, B. 2012. “CNN and Fox Trip Up in Rush to Get the News on the Air.” New York Times, June 28, 2012. https://www.nytimes.com/2012/06/29/us/cnn-and-foxs-supreme-court-mistake.html.

Sunstein, C. R. 1988. “Beyond the Republican Revival.” Yale Law Journal 97 (8): 1539–90.

Tate, K. 2003. Black Faces in the Mirror: African Americans and Their Representation in the US Congress. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Tyler, T. R. 2006. “Psychological Perspectives on Legitimacy and Legitimation.” Annual Review of Psychology 57:375–400.

Zilis, M. A. 2015. The Limits of Legitimacy: Dissenting Opinions, Media Coverage, and Public Responses to Supreme Court Decisions. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Note: throughout this chapter unless otherwise specified, when referring to support or approval of the Court, this is referring to the Court’s legitimacy. This is done simply to aid with the flow and readability of the paper. ↵

- The idea being that among other things, Congress and the presidency are evaluated based on what they have done. It is surprising that the Court is not evaluated in the same way. ↵

- Early political socialization includes things like our primary school education and the messages received from parents or guardians. ↵

- There were also pregnant chads where the chad was concave due to some pressure, but the perforations were not broken. ↵

- Very liberal, liberal, moderate (or “case by case basis” when discussing the Court), conservative, or very conservative. ↵

- For example, a subject who identified as very conservative and identified the Court as very conservative would have zero ideological disagreement, while someone who identified as a moderate or independent and said the Court was very conservative would have a disagreement level of two. ↵

- Of the thousands of cases that apply for certiorari, the Court only hears roughly one hundred each term, giving it an acceptance rate of around 1 percent (About the Supreme Court, n.d.). ↵

- While media appearances of Justices may be increasing (Hasen 2016), it is undeniable that Justices differ from elected officials in their conduct and statements during these appearances. ↵

- Famously in 2012, CNN and Fox News both misread the National Federation of Independent Businesses v. Sebelius decision and, incorrectly, announced that the Court had struck down the individual mandate in the Affordable Care Act (Seltzer 2012). ↵

- See Chong and Druckman (2007) for a thorough review of this literature. ↵

- Also see Nicholson and Howard (2003) who find that under some circumstances, like highlighting the consequences of a decision, the framing of a Supreme Court decision can harm the Court’s legitimacy. ↵

- A power given to the Supreme Court by the Supreme Court in Marbury v. Madison (1803). ↵

- Also sometimes called the countermajoritarian dilemma. ↵

- Important as well is that in addition to including a broader scope of cases which could even be considered countermajoritarian, Casper (1976) included the Warren Court and by extension the civil rights era, when the Court heard many cases challenging discriminatory state and local laws. ↵

- 576 U.S. 644. ↵

- Also see Hoekstra (2000) on local public opinion and Supreme Court decisions. Again, the concern about judicial review is that by overturning the decisions of a legislature the Court is acting against the will of the public and thus the Court is acting antidemocratically. This requires accepting the assumption that by overturning legislative decisions the Court is by extension overturning the public’s will. For a number of reasons such as race (Butler and Broockman 2011; Minta and Sinclair-Chapman 2012; Tate 2003), gender (Carroll 2003; Ditmar et al. 2018; Rosenthal 1998), or class (L. M. Bartels 2008; Domhoff 2006; Schattschneider 1960), we should be skeptical at best of the idea that the decisions and preferences of the elected branches represent the will of their constituents or voters more broadly. ↵

- Also see Franklin and Kosaki (1989) who studied the Court’s decision in Roe v. Wade and found that on one hand the decision increased support for abortions broadly while also increasing the polarization toward “discretionary” abortions. ↵

- But see Bartels and Johnston (2013), who argue the Court has moved somewhat to the left. ↵

- Convenience samples are not intended to be nationally representative, they are drawn from individuals recruited into a pool of subjects, rather than being drawn at random from the population at large. However, in the experimental literature, the use of a convenience sample is common and well regarded (Clifford and Jerit 2014; Mullinix et al. 2015). ↵

- For example, see Mondak (1992); Gibson, Caldeira, and Spence (2003b); Gibson, Lodge, and Woodson (2014); and Bartels and Johnston (2013). ↵

- Introductions to each passage and the text of the source cues come from experimental manipulations used by Gibson and Nelson (n.d.) ↵

- 558 U.S. 310. ↵

- Note, these items are based on a scale originally developed by Gibson, Caldeira and Spence (2003a). Additionally, they also produce a highly reliable scale with a Cronbach Alpha of .866. ↵

- But see Morgan and Young (2019). ↵

- Source cue (F(2,344) = 7.708, p = .001 n2 = .042). Criticism frame (F(2,344) = 3.219, p = .041 n2 = .017). ↵

- F(2,344) = 4.084, p = .018 n2 = .023. ↵

- F(2,344) = 3.141, p = .044 n2 = .018. ↵

- (F(2,344) = 6.712, p = .001 n2 = .037). ↵

- (F(2,288) = 7.744), p = .001 n2 = .049). ↵

- (F(2,288) = 8.32, p < .001 n2 = .053). ↵

- (F(2,288) = 5.728, p = .004 n2 = .036). ↵

- In some situations this positivity toward copartisans meant that they also viewed the bipartisan treatment more positively. ↵

- (F(2,114) = 3.851, p = .024). ↵

- (F(2,78) = 3.344, p = .04). ↵

- For terms here, what I mean is that based on the differences in how Democratic and Republican elected officials attack the Court, I associate Republicans with countermajoritarian language and Democrats with democratic process language. ↵