Media

31 The Language of Newspaper Coverage of the US Supreme Court

Douglas Rice

A previous version of this paper was presented at the 2018 Conference of the Midwest Political Science Association, Chicago, IL, April 5th-8th, 2018.

In describing the work of media coverage of the Supreme Court, celebrated newspaper reporter Linda Greenhouse writes that the “overwhelming impression that journalism about the Court—including my own—probably conveyed to the casual reader was of an institution locked in mortal combat, where sheer numbers rather than the force of argument or legal reasoning determined the result” (1996, 1551–52). Greenhouse, notably, is considered one of the most level-headed journalists covering the Court, most likely to present cases without the added dramatics of other reporters (Davis 1994; Solberg and Waltenburg 2014). In the context of a changing media environment and debate over the norms of coverage of the Supreme Court, Greenhouse’s perspective suggests a Court that is increasingly discussed by the media in terms of dramatic divisions.

What does this dramatization of the Court’s business mean for the public’s approval of the institution? In this study, I seek to understand how and whether changes in conflict reporting relate to (or reflect) the public’s perception of the Court. Understanding this relationship is especially important in light of recent declines in the public’s approval of the US Supreme Court, declines that have sparked hot takes from pundits, a series of alarmist posts from Gallup and other polling organizations, and recent academic inquiries (e.g., Sinozich 2017) all examining the causes and implications for the role of the Supreme Court in American politics. Studying coverage at all stages of the cases—rather than simply coverage of the decisions—and doing so across multiple newspapers over an extended period of the Court’s modern history, I provide evidence of changes in the extent to which major national newspapers cover conflict between justices as well as conflict between the Court and other political institutions.

The results suggest that reporting on the Court has increasingly focused on conflict between the justices. Moreover, changes in the emphasis on this conflict closely mirror changes in the Court’s public approval, at least as captured by one prominent measure. These results fit with a body of accumulated experimental evidence suggesting that exposure to division on the Court influences perceptions of the Court in terms of both policy acceptance or compliance and institutional legitimacy. In light of growing polarization on the Supreme Court, particularly following the confirmation battles and controversy surrounding Merrick Garland, Neil Gorsuch, and Brett Kavanaugh, the results offer evidence that the Court’s reservoir of goodwill may be at risk of drying up.

The Court as a Story

Media coverage is notorious for its sensationalism; as the saying goes, “If it bleeds, it leads.” Media select and craft stories in order to attract audiences, as would be expected in an industry that relies on readership and advertising dollars (e.g., Davis 1994; Zilis 2015). The Court’s institutional characteristics, however, make it a difficult subject for the sort of dramatic storytelling likely to garner audiences. Access to the Court is limited, deliberations regularly occur out of sight, and decisions are released as lengthy opinions cloaked with legal justifications. Legal language is generally dense and understated, and the Court itself is cloaked in symbols suggesting an exclusive and particularly high-minded form of discussion and debate (Davis 1994, 2011).

Nevertheless, newspaper coverage of the Supreme Court is tasked with attracting audiences, which is achieved by “generating drama and emphasizing conflict” (Zilis 2015, 29). Disagreements between justices, between litigants, and between the Court and other political actors are emphasized. Some cases lend themselves to such framing—for instance, the Obamacare decision—but the majority do not. Epstein and Segal (2000) find that only 15 percent of decisions receive front-page coverage in the New York Times the day after the decision. Similarly, Clark, Lax, and Rice (2015) demonstrate that coverage of cases across three major national newspapers exhibits strong positive skew, with most cases receiving no or very little coverage and a small number receiving extensive coverage throughout the life of the case on the Court’s docket.

The upshot is that many of the Court’s decisions are only minimally newsworthy in terms of what newspaper editors want, and those that are newsworthy present a distorted picture of the Court’s business (Solberg and Waltenburg 2014). Because so few cases receive media attention, most rulings never influence the public’s opinion of the Court, as the public is blissfully unaware of what the Court is doing (Marshall 1989; Franklin and Kosaki 1995; Zilis 2015). But where the media’s attention does turn to the Court’s activity, conflict and drama are more likely to be present (Zilis 2015), and—given the task of the reporter—the conflict and drama are likely to be highlighted and emphasized.

The Court has seemed acutely aware of this potential, seeking to control its image, reliant as it is on its legitimacy. As one of the seminal works on the topic notes, as of the early 1990s, “the justices have been stunningly successful in focusing the press’ attention on those aspects of the Court most beneficial to the achievement of the justices’ objectives, both those in support of the institution and those that support them as individuals” (Davis 1994, 114).

Yet there is reason to believe the Court’s ability to manage its public profile may have broken down. The changing media environment has yielded a far different emphasis in coverage across all areas of American life, and the Court has not been immune to that trend. Increasingly, journalists treat the Court as a political institution and the justices as political actors (Davis 2011; Solberg and Waltenburg 2014). Indeed, reporters covering the Court are aware of the changing environment. As Davis notes, there is an ongoing dispute among journalists covering the Court about the proper manner in which to discuss the institution and the decision-making process of the justices (Davis 2011). Should reporters treat the Court as a political institution with political actors in the broader political debate, or should the justices be treated as altruistic actors seeking resolutions in the law?

The question becomes particularly important when one considers whether media coverage affects public responses to the Court. Stated more simply, the question is whether coverage—particularly coverage focused on conflict—matters. This question is rooted in a rich and developing literature that has struggled to traverse the divide between the external validity of experimental results and understanding media coverage at scale. In one vein, work has looked to document the ability of the Court to encourage support for public policies in both observational (Marshall 1989; Mondak 1994) and experimental (Zilis 2015) work. Importantly, experimental work has also demonstrated the importance of the media in translating the Court’s decisions for the public in terms of generating acceptance (Clawson and Waltenburg 2003).

Still, acceptance of individual decisions is only a small part of—and indeed, may be shaped by (Zilis 2015)—a more fundamental characteristic of the Court: its institutional legitimacy. The debate over the proper manner to discuss the Court traces directly to concerns about treating the Court in a way that reduces its legitimacy. On this question, recent experimental and survey research suggest that responses to individual Court decisions or the perceived ideology of the Court may influence perceptions of the legitimacy of the institution under some conditions (Johnston and Bartels 2010; Bartels and Johnston 2013; Zilis 2015). Lost in these studies, however, is how changes in the broad environment of news coverage relate to or affect the long-term changes in public approval. That is, to remain tractable, scholars have regularly relied on a relatively small fraction of media coverage for relatively short periods of time, have examined coverage only of a limited number of cases, or have examined only survey or experimental work.

Thus I build from this work and address two questions. First, I examine whether—and if so, how—coverage of the Court has changed over time in terms of the conflictual content of newspaper coverage. If media reports have dramatized action in the Court as “mortal combat” and experimental work suggests that dramatization might matter for public approval of decisions and the institution, it is imperative to understand how that dramatization in coverage has changed over time. Second, how does the reporting of conflict relate to public approval of the institution over time? While experimental work suggests that exposure to conflict in the Court may decrease support for the institution, it is unclear how externally valid the observed relationships are. By examining a broad swath of media coverage in the media environment where dramatization is the most modest, therefore, I gain leverage on differences in the broad exposure to discussions of conflict on the Court and thus its connection to public approval of the institution.

Types of Conflict

I focus on two types of conflict present in newspaper coverage of Supreme Court cases: justice conflict, or the reporting of conflict between the justices, and political conflict, or the reporting of the Court’s role in political conflicts, particularly as it pertains to conflict with Congress or the president. While recognizing that the magnitude of conflict is variable across cases and disagreements, in this study I define conflict as any indication of disagreement among justices or between the Court and other institutions. In the following two sections, I describe and address how these types of conflict relate to the public approval of the institution.

Justice Conflict

One of many stories to come out of the Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education (1954) detailed the process of uniting a dividing Court in the name of public perception. When the case was first argued in 1952, the justices stood deeply divided (Klarman 2004). Then the chief justice at the time, Vinson, suddenly passed away, leading to his replacement with Earl Warren. As Klarman illustrates in striking detail, Warren set about bringing the Court to a unanimous decision in order to secure the judgment against backlash. In this landmark case, we can see the belief—held by the justices themselves—that conflict among justices detracts from support for the decisions of the Supreme Court and potentially from support for the institution itself.

Indeed, research provides some evidence this is the case. In experimental investigations, reporting unanimity was found to increase support for the Court’s decisions (Zink, Spriggs, and Scott 2009). Likewise, Zilis (2015) argues and finds evidence to suggest that the media covers dissensual—that is, divided—cases more unfavorably than consensual decisions. In presenting conflicting views, justices potentially decrease support for the decision and their institution.

In all, justices seem aware—and evidence suggests—that explicit division might carry institutional costs. Of course, it remains necessary that the public be aware of the division of opinion. To this end, media reporting on the Court has expanded discussions of the political ideologies and motivations of the justices, explicitly focusing on their differences. As an example, consider coverage of D.C. v. Heller (2008) in the Washington Post. The second sentence of the article states, “The Court’s landmark 5 to 4 decision split along ideological grounds,” while the author later states even more dramatically, “Stevens and especially Scalia often made their points in caustic and dismissive language. Throughout his opinion, Scalia used terms such as ‘frivolous’ and ‘absurdity’ to describe his opponents’ legal reasoning. Stevens made his unhappiness known by reading parts of his dissent from the bench, and he pointedly recalled for his conservative colleagues Justice Felix Frankfurter, whom he called a ‘true judicial conservative.’”

This language is no aberration. One recent study finds that articles covering the Court’s decisions generally devote very little space for the justifications, whether legal or political, offered by the justices for their decisions (Solberg and Waltenburg 2014). Yet the space devoted to ideological justifications has increased markedly from 1975 to 2009. This type of coverage emphasizes the ideological positioning of justices relative to the Court’s divisions (e.g., Roberts abandoning the conservatives in NFIB v. Sebelius) while dramatizing divisions on the Court—for instance, a “blistering” dissenting opinion (Solberg and Waltenburg 2014, 4). The focus on ideological divisions manifests in the tone of coverage, as conflicting coalitions that are ideologically homogenous receive particularly negative coverage (Zilis 2015). The potential effect is magnified by polarized responses to the Court’s dissensual decisions; as Nicholson and Hansford (2014) find, providing the partisan affiliation of the majority increases the acceptance of a Court decision among similarly affiliated survey respondents while decreasing the acceptance among those of the opposite part of the Court majority.

Taken together, there is good reason to suspect—from historical accounts of the Court’s decision-making, experimental research of exposure to dissensual frames, and our own understanding of newspaper coverage—that reporting of conflict between justices on the Court would decrease the public’s approval of the Court. Thus I focus here on the role of the media in shaping public perceptions of the Court.

Political Conflict

Beyond conflict between justices, it is also well accepted that the Court is increasingly an epicenter of American politics. As such, it reflects the polarization of the political system. Whether through juridification—the utilization of the judiciary for political ends (e.g., Silverstein 2009; Keck 2014)—or through the ideological fracturing of the Court, the Court today reflects the conflict occurring in American politics. Interest groups and others now regularly turn to courts to block policies they do not like and to encourage policies they do like. As Congress and the president become unwilling or unable to act amid a polarized political climate, the courts become an appealing avenue to pursue political change (e.g., Whittington 2007; Silverstein 2009). But by addressing the most important and contentious policies in American politics, the Court becomes more valuable as a political ally, and thus the Court is drawn into the polarized fights of the day.

Consider recent nomination battles. In 2015, controversy arose from the Republican Senate’s refusal to consider then president Barack Obama’s nomination of Merrick Garland to the Court. After Donald Trump was elected president, he subsequently nominated Neil Gorsuch to the still-open seat and thereafter widely publicized the nomination as evidence of the effectiveness of his presidency for the Republican cause. When Anthony Kennedy later stepped down from the Court, controversy erupted over President Trump’s nominee, Brett Kavanaugh. First, Republicans refused to release hundreds of thousands of documents relating to Kavanaugh’s activities during his time working for former Republican president George W. Bush, claiming that the documents were protected due to the sensitive and confidential nature of the discussions. Second, Kavanaugh’s hearing erupted when allegations of sexual misconduct surfaced; after a secondary hearing to discuss the allegations—in which US Senator Lindsey Graham memorably appealed to colleagues and members of the public—the nominee barely won confirmation with a vote of fifty to forty-eight.

With this sort of political battle playing out over the justices and the Court, the question is whether political conflicts might decrease the Court’s legitimacy. On this, prior evidence is mixed (Zilis 2015). While on some particularly hot-button issues the Court may alienate some citizens (Grosskopf and Mondak 1998), in general the Court can “damage its legitimacy only by issuing a series of high-profile and unpopular decisions in succession” (Zilis 2015, 13). Yet the Court is increasingly drawn into political arguments in a way that is central to American politics. As groups turn to the Court to resolve many of the day’s most important and divisive policy questions, the Court takes on yet more power. Indeed, as groups seek to use the Court in this way, reporters rely on those very groups to craft their news stories. Newspapers—and their coverage of conflicts in the Court—thus increase the value of shifting political conflicts into courts as rival groups seek to structure reporting. For instance, consider one recent article in the Washington Post discussing a recent lower-court decision to uphold restrictions on access to abortion. The article includes quotes from representatives of the American Civil Liberty Union’s Reproductive Freedom Project as well as the Center for Reproductive Rights. But as groups pursue political change through courts, they task the Court with resolving hot-button issues that carry institutional costs. Thus the Court’s involvement in political conflict—and any potential costs—may reach a threshold point at which it begins to deplete the public’s support for the institution.

Data

Taken together, these two types of conflict offer mechanisms by which the Court might lose the trust of the American public. To understand changes in coverage of these dimensions of conflict in Court reporting over time, I use coverage of Supreme Court cases across an extended period of time in three major national newspapers: the New York Times, the Washington Post, and the Los Angeles Times (Clark, Lax, and Rice 2015). The data offer two important advantages for the purpose of understanding changes in media coverage. First, by tracking coverage at all stages of the case and throughout the newspaper, the collection presents a comprehensive picture of media coverage of the Supreme Court. Second, and perhaps even more importantly, by including multiple newspapers across an extended period of time, the data cover the behavior of individual journalists, which is especially valuable given that some reporters prefer to take political and justice-centered approaches to reporting (i.e., Lyle Denniston, formerly of the Wall Street Journal and Boston Globe) while others take more law-centered approaches (i.e., Linda Greenhouse of the New York Times; Davis 1994; Solberg and Waltenburg 2014).

Understanding coverage across multiple newspapers at multiple stages of the case over an extended period of time presents a difficult setting for any human-coded content analysis. Further, the classification is especially difficult because I care about proportional change in coverage—that is, not whether conflict is present in the article but the extent to which conflict (and different types of conflict) are discussed. Therefore, testing for changes in coverage requires a granular measure of article content across this extended period of time.

To achieve this, I rely on methods for the computational analysis of text. In essence, I treat the texts of news articles—specifically, the individual sentences—as data, then develop statistical models that predict whether the sentence is discussing one of the types of conflict mentioned above. To begin, I split each article into sentence-level data using a computer program called Stanford CoreNLP, which has a wide variety of tools for analyzing and understanding texts (Manning et al. 2014). The result is a corpus—or collection of texts—that features 371,232 sentences. Clearly, classifying each of those sentences by hand is beyond the scope of a manual- or human-coding project. Instead, I rely on approaches from research on machine learning. Specifically, I utilize a supervised learning approach; these approaches operate by having a human construct a small, hand-coded data set, then “training” a statistical model that best predicts the codes assigned by the human. One can then employ the trained model to predict all the remaining classifications for the uncoded data.

For this project, I took a random sample of 5,000 sentences and hand-coded them into one of three categories: conflict among justices, conflict in politics, or neither. In the first case, I classify as conflict among justices any sentence in which a division of opinion among the judges is mentioned or implied. For instance, in a 1986 Washington Post article on Moran v. Burbine, the author reports, “O’Connor said the dissent’s misreading of Miranda is itself breathtaking in its scope.” In the second case, I classify instances where conflict in the political system is reported. As an example, in a 1998 article in the Los Angeles Times discussing Clinton v. City of New York, the author states, “It’s leading critics were staunch defenders of the prerogatives of the legislative branch and they exulted over Thursday’s court ruling.” Ultimately, 400 of the 5,000 statements are classified as justice conflicts (8 percent), while 305 of the 5,000 statements are classified as political conflicts (6.1 percent).

The goal of a supervised learning approach is then to take this small, hand-coded set of 5,000 sentences and—through statistical modeling —automate the coding of the more than 360,000 remaining sentences. To do so, I use the words of the sentences as variables and use the statistical model to find the words or phrases that best predict the assigned classifications (conflict among justices, conflict in politics, or neither). As an example, consider phrases like “Congress reacted” or “An evenly divided Court,” which might suggest political and justice conflict, respectively.

I then apply the statistical model—and the relationships it learns between the words used in a sentence and the assigned classification—to the more than 360,000 remaining sentences. For each sentence, the model provides a probability that the sentence belongs to each of the different classifications. For instance, given a sentence like “The 5-to-4 decision, with a majority opinion by Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, found the Court bitterly divided over the appropriate role for Federal law in the classroom,” the model might assign a probability of 0.97 to conflict between justices, 0.02 to conflict in politics, and 0.01 to no conflict. Using these probabilities, I code the proportion of an article devoted to justice conflict, or to political conflict, or to no conflict. To do so, I add up the conflict-type probabilities assigned to each sentence in an article and divide by the total number of sentences in the article.

Description

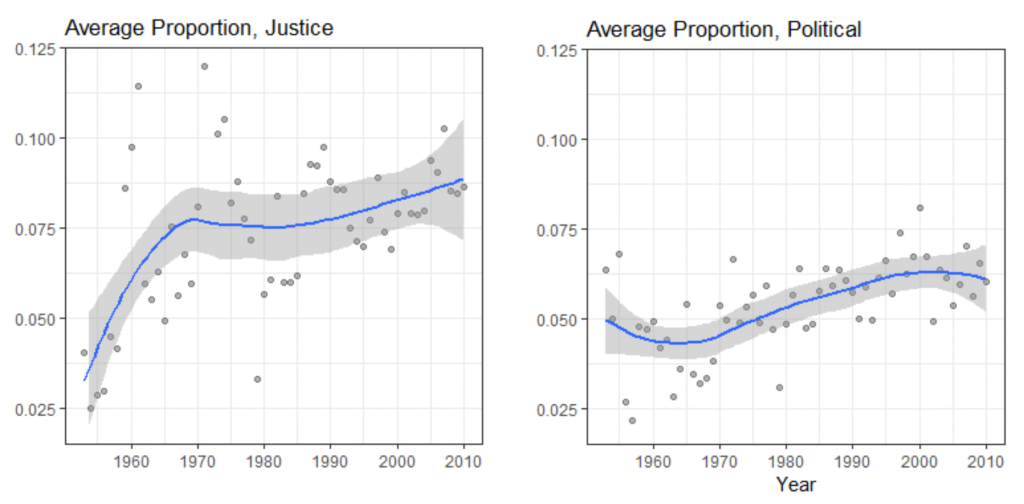

My interest is particularly in how the presence of conflict is changing over time. To that end, in figure 1, I plot the yearly average of justice conflict (left panel) and political conflict (right panel) for 1953 through 2010. For each plot, I include local polynomial regression fits (blue line) and associated 95 percent confidence intervals (gray shaded regions). The underlying idea of these lines is to allow for easier interpretation of data that have a lot of variation. The approach does so by calculating the average within some range of points, which is then plotted over the individual observations. Thus one can see both the individual observations (gray dots) as well as the general trends in the data. Turning to those trends, for justice conflict, there is a sharp increase in the reporting of conflict from the 1950s through the early 1970s. In the early 1970s—the early years of the Burger Court—newspaper coverage of the Court reached the highest individual values of reporting on justice conflict. Moving into the 1980s, however, reporting of conflict on the Court temporarily decreased before a spike in 1986—which happens to coincide with the famously irascible Justice Antonin Scalia joining the Court—that continues for a few years before marginally rescinding, with a gradual increase ever since.

While justice conflict experiences a substantial increase early in the time frame under study followed by a gentle increase throughout most of the rest of the series, political conflict exhibits a gradual increase across most of the time series, only plateauing in the 2000s. As might be expected, two of the highest years of political conflict include 1997, which featured executive privilege in Clinton v. Jones, and 2000, which featured one of the Court’s most politically charged cases ever in Bush v. Gore.

Before proceeding, I turn to assessing whether the newspaper-based measures of conflict offer information above and beyond the information that might be available through other measures of the concepts of interest. If newspaper coverage simply reflects underlying levels of justice conflict (as reflected in justice voting divisions) or political conflict (as reflected in court curbing by Congress), then there is little reason to focus on newspaper coverage.

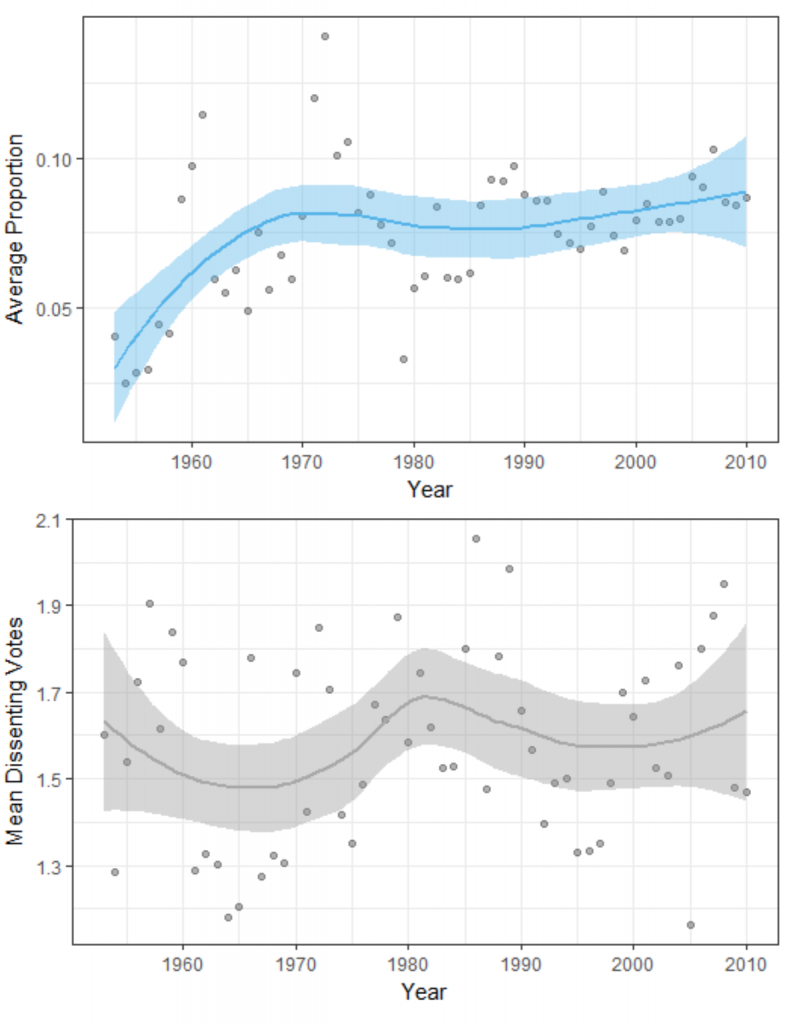

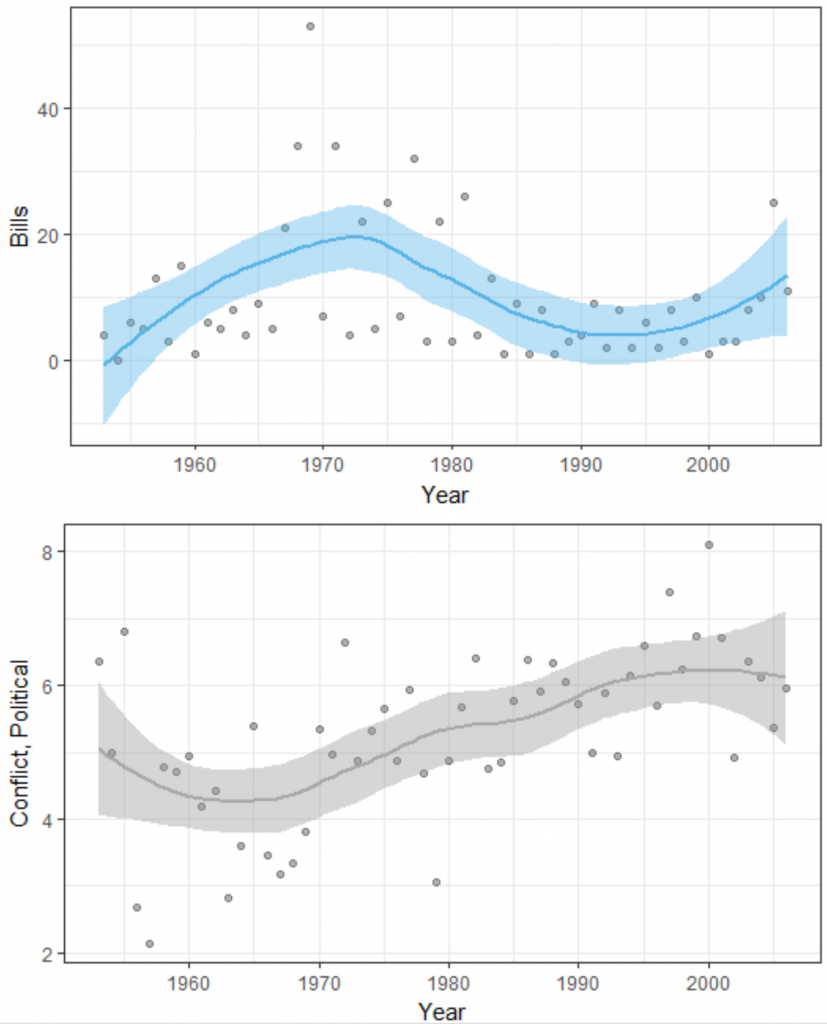

To see whether this is the case, in figure 2 I again plot the change in justice conflict (top panel) but compare changes in the justice conflict measure to changes in the average (mean) number of dissenting votes in all cases before the Court. I emphasize all, as the cases that receive attention from the media—particularly decision attention—are normally more controversial and thus conflictual (see, e.g., Davis 1994; Epstein and Segal 2000). The disparity is borne out by the comparison here. Neither series moves in concert with the other except for brief periods, most notably during the 2000s. As the comparison suggests, the correlation is weak, with ρ = 0.11, though higher values are obtained if the analyses are restricted to more recent terms. The focus of the newspapers, then, is not simply a reflection of changes in the voting divisions of the Court. Instead, newspaper reporting of conflict between justices seems to follow its own, unique trajectory that is only very weakly related to actual divisions on the Court.

I turn next to the relationship between political conflict and a related concept, the introduction of Court-curbing bills from Clark (2009). Court-curbing is defined by Clark as all bills introduced that aim at limiting the Court as an institution or bills that aim to limit particular opinions. In his work, Clark finds that the introduction of Court-curbing legislation does curtail the willingness of the justices to engage in political conflict. Here, the relationship between political conflict and Court curbing is stronger, as I find moderate but negative correlation between Court-curbing bills and the reporting of political conflict in articles covering US Supreme Court cases (ρ = −0.30). Still, though the two variables are correlated, the figure makes clear that newspaper reporting captures something unique about political conflict in which the Court is involved that goes above and beyond other observable measures of political conflict.

In all, we see evidence that the measures connect in interesting ways with theoretically relevant concepts that are frequently invoked in studies of public opinion and the Court’s legitimacy. Yet in both cases, the measures of conflict correlate only weakly (in the case of justice conflict) or moderately (in the case of political conflict) from their conceptual cousins. The presentation of the Court provided by newspapers differs in potentially important ways from the actual events and conflicts occurring at the Court. The media coverage, therefore, is not simply an inevitable part of the reporter dutifully covering events at the Court; rather, it reflects a unique perspective of those events. Returning to the research question, we have now seen how newspaper coverage of the Court has changed over time. Therefore, I turn next to analyzing whether these observed changes in newspaper coverage of justice and political conflict influence public approval of the Court.

Analysis

To understand the influence of newspaper coverage on public approval, one must have a measure of public approval. Unfortunately, as Clark (2009) notes, “Public opinion data about the Court are notoriously sparse” (979). In an experimental setup, one might garner some evidence of approval from a battery of questions all tapping into elements of institutional support and perceptions of institutional legitimacy (see, e.g., Gibson, Caldeira, and Spence 2003; Gibson et al. 2011; Bartels and Johnston 2013; Nelson and Gibson 2014). In nationally representative surveys covering a lengthy history of the Court’s approval, however, such batteries are absent.

Given the absence, I instead rely on Gallup’s institutional measure of support for the Supreme Court. Specifically, Gallup has asked the following question since 1973, worded consistently across years since 1983: “Now I am going to read you a list of institutions in American society. Please tell me how much confidence you, yourself, have in each one—a great deal, quite a lot, some, or very little?” I focus on responses to this question for the Supreme Court and aggregate the “great deal” and “quite a lot” responses as my measure of public approval.

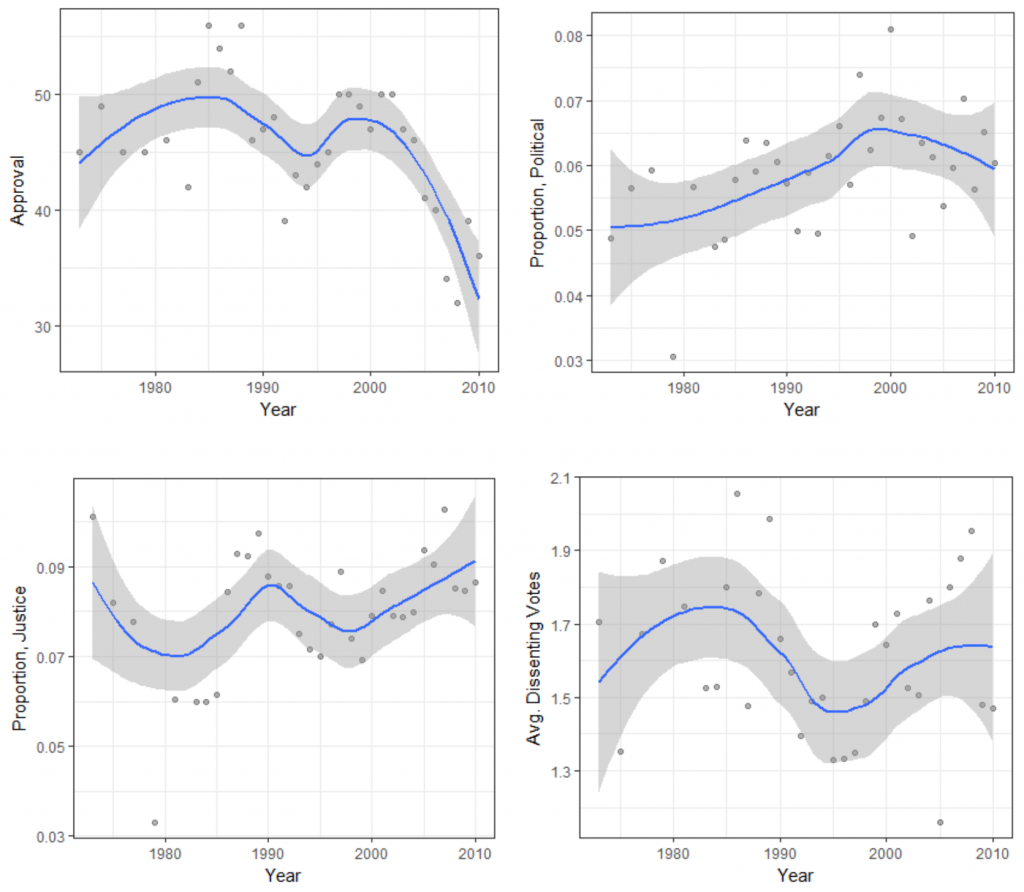

In the upper-left panel of figure 4, I plot the change in public approval of the Court over time as measured by Gallup. The results are striking. Following an increase in the late 1980s, approval decreased throughout the early and mid-1990s, increased in the years just before and just after 2000, and then dropped off a cliff around 2005. Indeed, this drop in prestige has been the subject of both popular and academic commentary (Sinozich 2017).

How does approval match our measures of conflict? In the upper-right panel, I plot the measure of political conflict over the same time series. Here, the reporting of political conflict has marginally decreased, on average, as public approval has decreased. On the other hand, both justice conflict (lower-left panel) and average dissenting behavior (lower-right panel) have exhibited increases in conflict in recent years. Of these two, however, justice conflict sticks out as a near mirror image of public approval—that is, as reporting of conflict between the justices increases, public approval decreases. If justice conflict does coincide with drops in institutional approval, as the figure suggests, it fits well with the experimental research suggesting that public exposure to individual statements of disagreement may dampen institutional support (e.g., Zink, Spriggs, and Scott 2009).

Of course, the figure is purely suggestive of the correlations between the measures. To test the relationships between the measures of conflict and the Court’s public approval, I rely on a regression model, which predicts changes in public approval (the dependent variable) using the measures of political conflict and justice conflict (my primary independent variables of interest) as well as a series of control variables.

I measure the effects of three independent variables, each of which appear in figure 4. Because of the short time series, I estimate a full model that includes each of the independent variables and also reduced models that include only the individual independent variable as a predictor in an error correction model (ECM) framework. The results appear in table 1.

| Variable | Full Model | Votes Model | Politics Model | Justices Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 23.01 (15.32) | 14.32 (9.08) | 6.16 (11.02 | 25.69 (10.10) |

| Change in Dissenting Votes | -0.28 (3.99) | -1.28 (3.82) | - | - |

| Change in Political Conflict | 0.14 (1.31) | - | 0.20 (1.16) | - |

| Change in Justices Conflict | -1.66 (1.23) | - | - | -1.67 (1.00) |

| Dissenting Votes t-1 | 0.64 (5.21) | -4.37 (4.77) | - | - |

| Political Conflict t-1 | 0.60 (1.54) | - | 0.32 (1.51) | - |

| Justices Conflict t-1 | -2.01 (1.05) | - | - | -2.01 (0.86) |

| Approval t-1 | -0.21 (0.15) | -0.17 (0.14) | -0.19 (0.14) | -0.21 (0.13) |

Table 1: Regression Model of Public Approval of the U.S. Supreme Court, 1984-2010

Note: N=26. The dependent variable in these analyses is public approval of the U.S. Supreme Court

In order to isolate the effect of media coverage on public approval of the Court, I pay close attention to time in setting up the model. The particular concern here is that contemporaneous public approval may also influence the independent variables. As an example, consider if the Court’s public approval declined markedly to historical lows; we might expect Congress or the president to enter into conflict with the Court more frequently in that situation. To address this, the models do not include the contemporaneous values of conflict. Instead, I include the value of each independent variable for the prior year, or the “lagged” values of the independent variables. Likewise, I include the change in each of the independent variables from the prior to the present year. In both cases, the goal is to ensure that the change in the independent variable actually occurred prior to the dependent variable. If the independent variable did not, of course, it could not cause any changes in public approval.

Across models, the only variable to attain standard levels of statistical significance is the lagged value of justice conflict. This particular modeling setup also allows one to analyze both the short-run effect and the long-run effect of an independent variable on a dependent variable. I start with the short-run effect. This can be interpreted as what would happen this year if the reporting of justice conflict increased last year. Here, we find that public approval of the Supreme Court would decrease by 0.35, a very modest effect. This is perhaps encouraging for those concerned with the potential decrease in Supreme Court legitimacy as a function of reporting, as an increase in a single year in the reporting of justice conflict would not substantially detract from the Court’s legitimacy in the immediate present. The Court, in other words, can withstand some negative reporting.

Yet perhaps more importantly, we can also look at the long-term effects, which give us an idea of how more reporting of justice conflict last year might influence public approval not just in the present year but in the many years to come. Here, the long-run effect is −9.64 and decays over five years. This indicates that increases in reporting of justice conflict lead to a substantial decrease of public approval spread over a number of subsequent years, given the relative inertia of public approval of the Court (Gibson, Caldeira, and Spence 2003; Nelson and Gibson 2014), this slow decay is sensible. However, for citizens interested in ensuring the continued legitimacy and approval of the Supreme Court, the results of this analysis are also quite alarming in light of changes in the coverage of the court. The Court might withstand instances of one or a couple of years of more negative reporting of conflict of justices, with the results suggesting that the effect is spread out over future years. However, if the Court received consistent coverage of justice conflict, the damage to the Court’s legitimacy is likely to be profound, as it accumulates over time.

Discussion and Future Directions

As Brett Kavanaugh was sworn in following a contentious and emotional confirmation process, media coverage turned toward how such a process might affect the relationships among the justices. One article, for instance, noted the alleged sexual misconduct, “as well as Kavanaugh’s angry denials and fierce criticism of Senate Democrats, widened the U.S. political divide just weeks before congressional elections and raised concerns about the court’s reputation in U.S. society.” Responding to such concerns, Justice Elena Kagan—in recent remarks reported later in the same article—stated, “I think especially in this time when the rest of the political environment is so divided, every single of [the justices] has an obligation to think about what it is that provides the court with its legitimacy.” These excerpts nicely illustrate the very tension this chapter highlights: while media coverage benefits from an emphasis on tension and conflict, the justices recognize and try—or at least say they try—to mitigate the appearance and expression of that conflict in order to maintain institutional legitimacy and approval. This chapter attempts to address which of the sides is prevailing in this persistent tension.

On this, a few points are clear. First, there has been an increase in media—at least in terms of prominent national newspapers of record—reporting of conflict between the justices. This increase does not match the rate of division within the Court, which is unsurprising given the selection of disputes for coverage (Zilis 2015). Importantly, however, I find evidence to suggest that whereas voting divisions on the Court do not relate to the Court’s approval among the public, the reporting of divisions does. Considered in light of the increase in media reporting of conflict and volatile recent Supreme Court confirmations, the research thus raises important questions: How might justices reach decisions and communicate those decisions to the public in an environment where expressions of conflict might be overly emphasized by the news media? How might reporters balance their important democratic role of educating the public—particularly in regards to a Supreme Court that is increasingly central in American politics—while also recognizing the potential detriment to the Court’s institutional legitimacy?

While the findings reported here are troubling to those interested in maintaining a strong and independent Court, much could be done in future research to clarify this effect and the concomitant danger to the Court’s legitimacy. One major conceptual hurdle lies in identifying whether the reporting directly influences public approval (as some of the experimental research suggests) or whether both the increases in the reporting of justice conflict and the decreases in public approval are instead reflective of the underlying polarization of American politics. If the justices are able to exert control over the appearance of conflict, some hope remains. However, if the Court’s ability to manage its image is compromised by the polarized political environment, the Court’s legitimacy might inevitably fall no matter the effort of the justices—a dire scenario for proponents of a strong and independent judiciary.

References

Bartels, Brandon, and Christopher Johnston. 2013. “On the Ideological Foundations of Supreme Court Legitimacy in the American Public.” American Journal of Political Science 57 (1): 184–99. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Clark, Tom. 2009. “The Separation of Powers, Court Curbing, and Judicial Legitimacy.” American Journal of Political Science 53 (4): 971–89. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Clark, Tom, Jeffrey Lax, and Douglas Rice. 2015. “Measuring the Political Salience of Supreme Court Cases.” The Journal of Law and Courts 3 (1): 37–65. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Clawson, Rosalee, and Eric Waltenburg. 2003. “Support for a Supreme Court Affirmative Action Decision: A Story in Black and White.” American Politics Research 31 (3): 251–79. (↵ Return)

Davis, Richard. 1994. Decisions and Images: The Supreme Court and the Press. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2) (↵ Return 3) (↵ Return 4) (↵ Return 5) (↵ Return 6)

———. 2011. Justices and Journalists: The U.S. Supreme Court and the Media. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. (↵ Return)

Epstein, Lee, and Jeffrey Segal. 2000. “Measuring Issue Salience.” American Journal of Political Science 44 (1): 66–83. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Franklin, Charles, and Liane Kosaki. 1995. “Media, Knowledge, and Public Evaluations of the Supreme Court.” In Contemplating Courts, edited by Lee Epstein, 352–75. Washington, DC: CQ Press. (↵ Return)

Gibson, James, Gregory Caldeira, and Lester Spence. 2003. “Measuring Attitudes Toward the United States Supreme Court.” American Journal of Political Science 47 (2): 354–67. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Gibson, James, Jeffrey Gottfried, Michael Delli Carpini, and Kathleen Hall. 2011. “The Effects of Judicial Campaign Activity on the Legitimacy of Courts: A Survey-Based Experiment.” Political Research Quarterly 64 (3): 545–58. (↵ Return)

Greenhouse, Linda. 1996. “Telling the Court’s Story: Justice and Journalism at the Supreme Court.” Yale Law Journal 105 (6): 1537–1561. (↵ Return)

Grosskopf, Anke, and Jeffery Mondak. 1998. “Do Attitudes Toward Specific Supreme Court Decisions Matter? The Impact of Webster and Texas V. Johnson on Public Confidence in the Supreme Court.” Political Research Quarterly 51 (1): 633–54. (↵ Return)

Johnston, Christopher, and Brandon Bartels. 2010. “Sensationalism and Sobriety: Differential Media Exposure and Attitudes Toward American Courts.” Public Opinion Quarterly 74 (2): 260–85. (↵ Return)

Keck, Thomas. 2014. Judicial Politics in Polarized Times. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. (↵ Return)

Klarman, Michael. 2004. From Jim Crow to Civil Rights: The Supreme Court and the Struggle for Racial Equality. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. (↵ Return)

Manning, Christopher D., Mihai Surdeanu, John Bauer, Jenny Finkel, Steven J. Bethard, and David McClosky. 2014. “The Stanford CoreNLP Natural Language Processing Toolkit.” In Association for Computational Linguistics (Acl) System Demonstrations, 55–60. http://www.aclweb.org/anthology/P/P14/P14-5010 (↵ Return)

Marshall, Thomas. 1989. Public Opinion and the Supreme Court. Boston, MA: Unwin Hyman. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Mondak, Jeffery. 1994. “Policy Legitimacy and the Supreme Court: The Sources and Contexts of Legitimation.” Political Research Quarterly 47 (3): 675–92. (↵ Return)

Nelson, Michael, and James Gibson. 2014. “Is the US Supreme Court’s Legitimacy Grounded in Performance Satisfaction and Ideology?” American Journal of Political Science 59 (1): 162–74. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Nicholson, Stephen, and Thomas Hansford. 2014. “Partisans in Robes: Party Cues and Public Acceptance of Supreme Court Decisions.” American Journal of Political Science 58 (3): 620–36. (↵ Return)

Silverstein, Gordon. 2009. Law’s Allure: How Law Shapes, Constrains, Saves, and Kills Politics. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Sinozich, Sofi. 2017. “Public Opinion on the US Supreme Court, 1973–2015.” Public Opinion Quarterly 81 (1): 173–95. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Solberg, Rorie Spill, and Eric Waltenburg. 2014. The Media, the Court, and the Misrepresentation: The New Myth of the Court. New York, NY: Routledge. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2) (↵ Return 3) (↵ Return 4) (↵ Return 5) (↵ Return 6)

Whittington, Keith. 2007. Political Foundations of Judicial Supremacy the Presidency, the Supreme Court, and Constitutional Leadership in US History. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. (↵ Return)

Zilis, Michael. 2015. The Limits of Legitimacy. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2) (↵ Return 3) (↵ Return 4) (↵ Return 5) (↵ Return 6) (↵ Return 7) (↵ Return 8) (↵ Return 9) (↵ Return 10) (↵ Return 11) (↵ Return 12)

Zink, James, James Spriggs, and John Scott. 2009. “Courting the Public: The Influence of Decision Attributes on Individuals’ Views of Court Opinions.” The Journal of Politics 71 (3): 909–925. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Class Activity

Covering Conflict at the Supreme Court

The US Supreme Court is regularly asked to resolve some of society’s biggest public policy problems, yet the justices also regularly seek to craft an image of the Court as above the partisan political process. For this assignment, you are to find a newspaper article covering a policy problem the US Supreme Court is expected to address before the end of its present or upcoming term. Using the course website, sign up for one of the cases presently pending before the Supreme Court. Then find an article in a major newspaper (e.g., New York Times, Washington Post) or major online media outlet (e.g., Vox.com) discussing the case. Write a three- to four-page response paper detailing the public policy issue, the case, and the following aspects of coverage:

- What legal arguments (e.g., precedent, constitutionality) does the article discuss?

- What political arguments (e.g., ideology, political parties) does the article discuss?

- How many sentences are in the article?

- How many sentences discuss conflict between the justices? What, if any, is an example?

- How many sentences discuss conflict between the Court and other institutions? What, if any, is an example?

Your paper will be due at the beginning of class. Be prepared to discuss your article in class. For instance, if these results hold, should the media change? Whose job is it to maintain the legitimacy of the Court?