Public Opinion

27 Influence of Politicians on Public Support for the Judiciary

Miles T. Armaly

Conventional wisdom suggests that members of the American mass public are strong proponents of an independent judiciary, and as a result, support for the Supreme Court is unaffected by the behavior of the political branches. Indeed, decades of evidence show that most Americans support the US Supreme Court even when it makes decisions with which they disagree (Caldeira and Gibson 1992; Gibson, Caldeira, and Spence 2005). This chapter asks what might happen to support for the judiciary if the political branches began attacking the Supreme Court.[1] In other words, would ordinary citizens continue to support the Court, or would they listen to their preferred politicians? And what might this mean for the judiciary?

By and large, Americans support the federal judiciary. According to a 2018 Gallup poll, nearly 80 percent of Americans said they had at least some confidence in the Supreme Court; only 50 percent of people said the same for Congress. The reasons for this support are myriad. For starters, even though many do not believe the Court to actually be removed from politics, it does not behave like other political institutions. For instance, the Court’s debates occur in secret, whereas congressional debates—such as confirmation hearings—are broadcast on television and are often open to the public. Thus if there is hostility among the Supreme Court justices, such rancor is hidden from the public; the same is not true for Congress. Additionally, the judiciary tends to ground its decisions in legal precedent, lending more credibility to its claims. Moreover, the Court uses many symbols—such as robes and gavels—that remind people about the importance of the law and justice; these symbols lead people to have a “positivity bias,” or a favorable predisposition, toward courts (Gibson and Caldeira 2009; Gibson, Lodge, and Woodson 2014). These differences between the judiciary and the other branches of government frequently help gird support for the institution. However, the single-most glaring difference between the judiciary and other institutions—that its members are appointed, not elected—can place the Court in a unique and precarious position that influences the legitimacy on which the Court relies.

Institutional legitimacy is a prerequisite for governing. Institutions that are considered legitimate are viewed as having rightful and justified authority to exercise the powers that are vested in the office. In the United States, most institutions—such as the presidency, Congress, and state legislatures—are seen as legitimate due to free and fair elections. Even people who are disappointed with electoral outcomes still perceive the winners to have the authority to enact laws and enforce them. However, because members of the federal judiciary are appointed instead of elected, they do not receive this important form of political capital (i.e., the ability to make respected decisions; political influence) through elections. Instead, institutional legitimacy for the federal judiciary must come in the form of public support. Public support is essential for the Court because it relies on the other branches to enforce its decisions. As Alexander Hamilton wrote in Federalist 78, the judiciary has “no influence over either the sword or the purse. . . . It may truly be said to have neither FORCE nor WILL, but merely judgment.” That is, the judiciary has neither the power nor the funds to execute its decisions. Instead, the president, legislature, and state governments (i.e., elected officials) must enforce them. However, members of the elected branches are primarily motivated by reelection (Mayhew 1974). They are unlikely to enforce a Supreme Court decision when the Court is unpopular (i.e., when doing so may cost them votes in the next election). For proof, we need look no further than the refusal to desegregate schools in the American South after Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (347 U.S. 483, 1954) or, more recently, the refusal of some county clerks to issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples after Obergefell v. Hodges (135 S. Ct. 2584, 2015). So the Court derives its legitimacy via public support for the institution and its decisions. If the public supports the institution, elected officials will enforce its decisions (Clark 2009; Ura and Wohlfarth 2010).

The major question, then, is whether politicians are capable of diminishing the Court’s legitimacy and thereby its ability to make decisions that are enforced. For the reasons mentioned above, conventional wisdom suggests that politicians cannot. Generally speaking, people support a judiciary that is free from meddling by the political branches. However, in recent years, Americans have become increasingly reliant on “cues,” or pieces of information on how to act, from politicians. These cues are said to have a “dominating impact” on citizen’s positions (Cohen 2003), such that they “follow the leader,” or simply adopt a preferred politician’s policy positions (Lenz 2012). And these cues have been shown to influence attitudes regarding the Supreme Court, where Democrats like a specific court decision more when they believe a “Democratic majority” reached it and vice versa (Nicholson and Hansford 2014), as well as the willingness to pass legislation that reduces the judiciary’s ability to act (Clark and Kastellec 2015). So despite the conventional wisdom that average citizens are predisposed to have positive attitudes about the Court (Gibson and Caldeira 2009), there is reason to believe that statements regarding the Court from a preferred political figure might impact views of the judiciary.

To find out if politicians can influence public attitudes about the Court, I conducted two survey experiments—one about Hillary Clinton and one about Donald Trump.[2] Participants were asked a series of questions that measure how legitimate they think the Court is. These legitimacy questions, designed by Gibson, Caldeira, and Spence (2003) and listed below, ask how much one agrees or disagrees, on a 5-point scale, with statements regarding the Court’s independence. More specifically, they gauge an individual’s willingness to make lasting changes to the institution. Those supportive of making such changes believe the Court is less legitimate than those who disagree with making these changes.[3]

- If the Supreme Court started making decisions that most people disagree with, it might be better to do away with the Court.

- The right of the Supreme Court to decide certain types of controversial issues should be reduced.

- The US Supreme Court gets too mixed up in politics.

- Justices who consistently make decisions at odds with what a majority of the people want should be removed.

- The US Supreme Court ought to be made less independent so that it listens a lot more to what the people want.

- We ought to have a stronger means of controlling for actions of the US Supreme Court.

- The Court favors some groups more than others.

To determine how much legitimacy an individual thinks the Court has, I take his or her average response across all seven legitimacy items. A high score means that somebody thinks the elected branches should leave the judiciary be, whereas low scores indicate that somebody thinks the Supreme Court has too much authority and should be less independent.

Some respondents were randomly assigned to answer these legitimacy questions a second time (after answering demographic questions such as age, income, and education so that they wouldn’t remember their original answers). Others were randomly assigned to read the following sentence:

Recently, in a speech given to supporters, Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton [in the Trump experiment: “president-elect Donald Trump”] made some controversial remarks regarding the United States Supreme Court. Below, some of her [his] critiques will be paraphrased. Please indicate your level of agreement with Hillary Clinton’s [Donald Trump’s] statements.

The people who read this sentence were asked the original legitimacy questions again, but this time, they were told that Hillary Clinton (in Experiment 1) or Donald Trump (in Experiment 2) had made those hostile statements about the Court. For example, instead of responding to the question above, they read, “Hillary Clinton commented, ‘The Supreme Court ought to be made less independent’ so that it listens a lot more to what the people want. Do you agree or disagree?”[4]

To find out if these statements changed people’s minds about the Supreme Court after hearing the hostile statements, I subtract the average response from the first set of answers from the average response from the second set. I then rescale this variable from −1 to 1, such that positive values mean an increase in institutional support, or legitimacy, and negative values mean a decrease in institutional support. Importantly, I also ask people how they feel about Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump. To do so, I employ a “feeling thermometer,” which measures “affect,” or one’s emotional reaction, toward the political figure. Temperatures range from 0 to 100, where 0 means a person is extremely “cold,” or does not like the politician, and 100 means he or she is extremely “warm,” or very much like the politician. The midpoint, 50, means a person neither likes nor dislikes the politician. This is a useful way to determine how one feels about the figure purported to denounce the Court, as we can be more certain that this measure of pure affect relates directly to the politician as opposed to his or her ideology or the party he or she represents. Consider the specifics of the 2016 election; many Democrats did not like Clinton, and many Republicans did not like Trump. Measuring individuals’ emotional reactions to these figures is different than asking if they like the political party, if they respect the candidate, or if they agree with the candidate ideologically.

The expectation is that people who like Donald Trump will exhibit less support for the Court upon hearing his negative comments about the Court. A person may think, “I like (i.e., am affectively positive toward) Donald Trump, and he just criticized the Court, so I must like the Court less than I thought.” Conversely, people who dislike Donald Trump may have the opposite reaction: “I loathe Donald Trump, and he seemingly dislikes the Court, so I must like the Court more than I thought.” I expect the same relationship regarding Hillary Clinton; her supporters will believe the Court to be less legitimate after hearing her statements, and her detractors will offer more support to the Court.

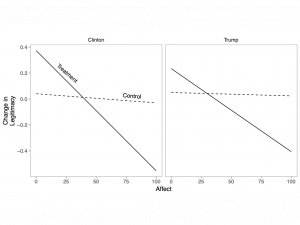

Figure 1 shows the degree to which affect toward either Trump or Clinton influences institutional support for the Supreme Court for both people in the experimental treatment (i.e., those who believe Trump or Clinton said negative things about the Court) and those in the control group (i.e., those who simply responded to the legitimacy questions twice without reading any statement by Trump or Clinton). People who are not led to believe that Trump or Clinton said the Court should be less independent should not change their views about the Court whatsoever. This is precisely what is borne out in the data. In both the Clinton panel (at left) and the Trump panel (at right), the solid line marked “control” is relatively flat (i.e., is not statistically different from 0). In other words, support for the Court is consistent, meaning control-group individuals respond to the seven legitimacy questions in a similar fashion the first time they encounter them as the second time.

When looking at the dashed lines marked “treatment,” however, a different story unfolds. Beginning in the Clinton panel, individuals who dislike Clinton—that is, those whose affect toward her is between 0 and 30—increase their level of support for the Court after hearing her negative statements. Thus these individuals may think, “I dislike Clinton, and she dislikes the Court, so I must like the Court.” This effect is similar for those opposed to Trump; from affect levels from 0 to 20, individuals increase their support for the Court upon hearing Trump’s negative statements. For both politicians, the effect is statistically different from the control group for these values (at p < 0.05 level).

When examining those who are middling in their affect toward both figures—around 30 to 55 for Clinton and 20 to 50 for Trump—the effects are inconclusive. That is, individuals in those ranges do not change their opinions about the Court; the effect is not statistically different from the control group for these values (i.e., is not significant). This is sensible. People who aren’t sure how they feel about Trump or Clinton but neither love nor loathe them are less likely—relative to somebody who for certain knows her feelings toward the figure—to bring that affect to bear on the Supreme Court.

Finally, those who are generally positive toward the figures—around 55 to 100 for Clinton and 50 to 100 for Trump—decrease their support for the Court. The effect is statistically significant (i.e., statistically different from the control group) in this range. That is, a Trump supporter might think, “I love Trump, and he dislikes the Court, so I must dislike the Court.” And these effects are largest for the staunchest Clinton and Trump supporters, such that individuals who adore these politicians end up disliking the Court. Overall, these are substantively large effects. Across the range of affect, the decrease in legitimacy is 0.64 units, or about 32 percent of the range of change in legitimacy, for Trump; for Clinton, these values are 0.93 units and 46 percent of the range. In other words, relative to people who dislike the politicians, those who like them have radically different views of the Court upon hearing the figure speak of the judiciary.

This is a problematic discovery for the constitutional role of the Supreme Court in American democracy. The Court is intended to be immune from political pressures. As Hamilton suggests in Federalist 78, federal judges are appointed for life precisely to avoid consideration of the political whims of the day. Yet the Court requires public support in order to expect compliance with and enforcement of its decisions. The executive, legislature, and state governments must assist the Court in implementing its decisions. And they are likely to do so when the public supports the Supreme Court. However, as these results show, political figures themselves are able to influence public support for the Court. Democratic theory suggests that political figures ought to be bound by public will; here, we see that they can influence what the public wants. Consider a politician who suspects that the Court will rule to uphold affirmative action. The results here suggest that the politician can merely promote dislike of the Court among his supporters in order to create a circumstance where (A) he does not have to enforce the affirmative action ruling and (B) he is potentially not punished for failing to enforce the ruling.

More broadly, politicians may rhetorically attack the Court in order to avoid the repercussions of failing to acquiesce to an unfavorable Court decision or to turn public tides away from the Court. Consider President Trump tweeting, “How broken and unfair our Court System is,” or suggesting that the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals should be broken up into two or three courts (Brennan Center for Justice). Certainly, his supporters would be suspect of any decisions from the Ninth Circuit, and they may believe the Supreme Court to be less legitimate in cases where it upholds a decision from the Ninth Circuit. Importantly, Trump is not the only political actor to criticize the Supreme Court (although few have done so as blatantly); President Obama was a vocal critic of the judiciary (Jaffe 2015).

Affect, or Learning about the Court?

Above, I assert that affect toward Donald Trump or Hillary Clinton influences people’s attitudes regarding the Supreme Court. Indeed, people who like the politician express dislike for the Court and vice versa when they hear the politician publicly decry the judiciary. One alternate explanation for this effect is that people are learning something about the Court. Most people do not know much about the Court’s political position (Bartels and Johnston 2013). Many people can rightly state that Congress is either liberal or conservative at any given point in time. They can do the same for the president. But they struggle mightily to accurately complete this task for the Supreme Court (Hetherington and Smith 2007). So it may be that hearing information from Trump or Clinton reveals to an individual whether the Court is ideologically similar to him . Thus instead of thinking, “I like Clinton, and she dislikes the Court, so I must dislike the Court,” an individual who learns something from Clinton’s statements might think, “I know Clinton is liberal, and she dislikes the Court, so the Court must be conservative.” In other words, one might update how ideologically distant he feels from the Court and alter his level of support accordingly. If this were the case, it would be much less worrisome for the Supreme Court. For an individual to react negatively to an institution with which he politically disagrees is much less troublesome than a politician’s ability to influence public attitudes about the Court.

To find out if affect or learning something new about the Court influences institutional support, I use the data described above. To determine how ideologically distant one feels from the Court, I ask survey respondents to describe their own ideology on a 5-point scale, ranging from extremely liberal to extremely conservative. Then I ask them to describe where they believe the Court is on the same 5-point scale and take the absolute value of the difference between these two properties. I ask respondents to do this both before and after they read the comments by Trump or Clinton about the Court.

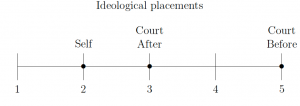

Consider figure 2, which gives an example of this 5-point ideology scale. An individual places herself at a moderately liberal position, 2. Before she hears Trump or Clinton’s statements, she perceives the Court to be at an extremely conservative position, 5. Thus her perceived ideological distance from the Court is 3 units. After hearing the statements, she adjusts her position of the Court, now perceiving it to be moderate, at 3, which is 1 unit from her position. The variable of interest is the change in perceived ideological distance. To calculate this, I subtract the before distance (3) and from the after distance (1). So in the example in figure 2, the change in ideological distance equals −2, which means the perceived distance between an individual and the Court decreased. That is, the respondent in figure 2 perceived the Court to be closer to her in ideological space based on the statements she heard from the politician. This variable ranges from −4 to 4, where positive values mean the perceived distance between oneself and the Court has grown larger after hearing a politician’s negative statements, and negative values mean one feels closer to the Court in ideological terms.

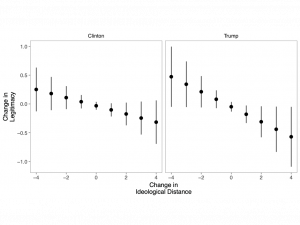

Figure 3 shows the effects of change in ideological distance on the change in institutional support. Each dot is the estimated effect of the change in ideological distance on the change in support, or legitimacy. The vertical lines around the dots are 95 percent confidence intervals. When one of these vertical lines also intersects 0.0 on the y-axis, it means there is no meaningful effect at that level of change in ideological distance. So despite the downward slope, there is no actual effect of change in ideological distance on change in diffuse support; the effect is not statistically significant. This means that respondents are not learning new information about the Court when they hear Trump or Clinton’s negative statements about the judiciary. That is, they are not ideologically updating. Instead, as we learned in figure 1, it means people react to the politician’s statements based exclusively on whether they like the politician. Respondents who like Clinton suddenly dislike the Court not because they find out the Court is more conservative than they originally thought but because they like Clinton.

During his 2010 State of the Union address, President Obama rebuked the Supreme Court’s recent decision in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission (558 U.S. 310, 2010). He began, “With all due deference to the separation of powers” before lambasting the Court for reversing “a century of law.” Vice President Joe Biden was less subtle in the days that followed. He said the decision was “dead wrong” and that “we have to correct it,” calling into question the Court’s final word on a constitutional matter. Moreover, he noted that President Obama “questioned the judgment” of the Court. Although a single decision ignited this political kerfuffle, not everybody believed this was merely a complaint about the Citizens United case. Senator John Cornyn, a Republican, more directly tied Obama’s comments to the constitutional justification for independence. He remarked, “I don’t think the president should have done what he did in trying to call out the Supreme Court for doing its job. They are the final word on the meaning of the United States Constitution, even when we don’t like the outcome” (Williams, O’Donnell, and Strickland 2010).

What happens when political figures speak out against the Supreme Court? The evidence here suggests that politicians can compel their supporters to disagree with the Court. However, it also suggests that those opposed to politicians may support the judiciary more based on politicians’ statements. Nevertheless, malleability in the evaluations of the institution that provide it with political capital is problematic.[5] Should we worry about the Supreme Court’s legitimacy? It seems that some justices already do. In a 2017 speech, Chief Justice John Roberts remarked, “It is a real danger that the partisan hostility that people see in the political branches will affect the nonpartisan activity of the judicial branch” (quoted in Greenhouse 2017). Although Roberts did not discuss how the Court might react to this hostility, it is clear the judiciary is considering the way it is discussed and how that may influence members of the mass public. Even members of the elected branches have recognized this threat. President Obama warned that when people “just view the courts as an extension of our political parties,” public trust in the judicial branch can be harmed (quoted in Lithwick 2016). So as the evidence presented here suggests, Chief Justice Roberts and President Obama may rightfully be concerned about the political branches actively seeking to influence public attitudes regarding the Supreme Court.

An important component of this influence is that prominent politicians may be required to actively decry the Court in order to compel followers to disagree with the judiciary’s rulings (although we cannot conclusively test this with these data). This fact may assuage concern among some, as historically speaking, criticism of the Court by political figures was rare (Totenberg 2017). Modern presidents increasingly voice disappointment with the Supreme Court and about rulings with which they disagree. For instance, one journalist asked, “Why does President Obama criticize the Supreme Court so much?” (Jaffe 2015). Another noted that President Bush once remarked, “We’ll abide by the Court’s decision. That doesn’t mean I have to agree with it,” and even though past presidents have been harsh with the Court, President Trump is “out of line with past presidents” (Totenberg 2017). Altogether, it seems that major political figures do criticize the Court, making very real the possibility that they might compel their followers to ignore the Court and thereby reduce the power of its rulings.

One critical consideration is whether there are differences in criticizing a particular decision (which might decrease specific support) and criticizing the Court and its justices more generally (which might decrease legitimacy). In this chapter, I do not differentiate between the two types of criticisms, nor can we ascertain how they may influence the public from the analyses above. However, one way for the Court to build legitimacy is by deciding a sequence of cases with which one agrees on policy grounds (Gibson, Caldeira, and Baird 1998). But people do not know much about the Court, nor do they necessarily understand if a decision was pleasing. And as the quote by Senator Cornyn suggests, complaints about a particular decision reflect more broadly on the institution itself. So I suspect that a politician to whom one looks for cues may be able to influence attitudes toward the Court, whether the criticism be of a single decision, of the Court itself, or of a particular justice. Interested readers should consider the difference and how various political attacks might differentially influence the Court.

Finally, what is not considered here—and that curious readers may ponder—is how notorious one needs to be to influence public attitudes regarding the Supreme Court. Can only presidents and presidential candidates influence the public? What about congresspersons, or governors, or political media personnel? For what reasons may these individuals be able to influence the public? For what reasons might they not be able to? If only the most influential political figures are capable of harming the Court, we may rest easy. However, should many individuals be capable of influencing public evaluations of the judiciary, consternation may be more warranted.

References

Bartels, Brandon L., and Christopher D. Johnston. 2013. “On the Ideological Foundations of Supreme Court Legitimacy in the American Public.” American Journal of Political Science 57 (1): 184–99. (↵ Return)

Brennan Center for Justice. 2017. “In His Own Words: The President’s Attacks on the Courts.” Brennan Center for Justice, June 17. https://www.brennancenter.org/analysis/his-own-words-presidents-attacks-courts (↵ Return)

Caldeira, Gregory A., and James L. Gibson. 1992. “The Etiology of Public Support for the Supreme Court.” American Journal of Political Science 36: 635–64. (↵ Return)

Clark, Tom S. 2009. “The Separation of Powers, Court-curbing, and Judicial Legitimacy.” American Journal of Political Science 53 (4): 971–89. (↵ Return)

Clark, Tom S., and Jonathan P. Kastellec. 2015. “Source Cues and Public Support for the Supreme Court.” American Politics Research 43: 504–35. (↵ Return)

Cohen, Geoffrey L. 2003. “Party Over Policy: The Dominating Impact of Group Influence on Political Beliefs.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 85 (5): 808–22. (↵ Return)

Gibson, James L., and Gregory A. Caldeira. 2009. Citizens, Courts, and Confirmations: Positivity Theory and the Judgments of the American People. Princeton: Princeton University Press. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Gibson, James L., Gregory A. Caldeira, and Vanessa A. Baird. 1998. “On the Legitimacy of National High Courts.” American Political Science Review 92 (2): 343–58. (↵ Return)

Gibson, James L., Gregory A. Caldeira, and Lester Kenyatta Spence. 2003. “Measuring Attitudes toward the United States Supreme Court.” American Journal of Political Science 47 (2): 354–67. (↵ Return)

Gibson, James, Gregory Caldeira & Lester Spence. (2005). Why Do People Accept Public Policies They Oppose? Testing Legitimacy Theory with a Survey-Based Experiment. Political Research Quarterly,58(2), 187-201. doi:10.2307/3595622 (↵ Return)

Gibson, James L., Milton Lodge, and Benjamin Woodson. 2014. “Losing, but Accepting: Legitimacy, Positivity Theory, and the Symbols of Judicial Authority.” Law & Society Review 48 (4): 837–66. (↵ Return)

Greenhouse, Linda. 2017. Will Politics Tarnish the Supreme Court’s Legitimacy?” The New York Times. 26 October 2017. Available: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/26/opinion/politics-supreme-court-legitimacy.html?rref=collection%2Fsectioncollection%2Fopinion (↵ Return)

Hetherington, Marc J., & Joseph L. Smith. (2007). Issue Preferences and Evaluations of the U.S. Supreme Court. (↵ Return)

Jaffe, Greg. 2015. “Why Does President Obama criticize the Supreme Court so much?” The Washington Post, June 20. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/why-does-president-obama-criticize-the-supreme-court-so-much/2015/06/20/b41667b4-1518-11e5-9ddc-e3353542100c_story.html (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Lenz, Gabriel S. 2012. Follow the Leader: How Voters Respond to Politicians’ Policies and Performance. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. (↵ Return)

Lithwick, Dahlia.2016. “Chuck Grassley’s Supreme Court Coup.” Slate. 7 April 2016. http://www.slate.com/articles/news_and_politics/jurisprudence/2016/04/sen_chuck_grassley_attacks_the_supreme_court_john_roberts.html (↵ Return)

Mayhew, D. R. (1974). Congress: The electoral connection. New Haven: Yale University Press. (↵ Return)

Nicholson, Stephen P., and Thomas G. Hansford. 2014. “Partisans in Robes: Party Cues and Public Acceptance of Supreme Court Decisions.” American Journal of Political Science 58 (3): 620–36. (↵ Return)

Totenberg, Nina. 2017. “Trump’s Criticism of Judges Out of Line with past Presidents.” The New York Times, February 11. http://www.npr.org/2017/02/11/514587731/trumps-criticism-of-judges-out-of-line-with-past-presidents (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Ura, Joseph Daniel, and Patrick C. Wohlfarth. 2010. “An Appeal to the People: Public Opinion and Congressional Support for the Supreme Court.” The Journal of Politics 72 (4): 939–56. (↵ Return)

Williams, Pete, Kelly O’Donnell, and Ken Strickland. “Justice openly disagrees with Obama in speech.” NBC News, January 28. http://www.nbcnews.com/id/35117174/ns/politics-white_house/t/justice-openly-disagrees-obama-speech/ (↵ Return)

Empirical exercise

Students calculate their diffuse support scores and their perceived ideological distance scores, and the class determines if there is a correlation (either by calculating or guesstimating, based on responses) between the two.

Diffuse support score

Indicate whether you strongly agree (1), somewhat agree (2), neither agree nor disagree (3), somewhat disagree (4), or strongly disagree (5) with each of the items below. Be sure to keep track of your score.

- If the Supreme Court started making decisions that most people disagree with, it might be better to do away with the Court

- The right of the Supreme Court to decide certain types of controversial issues should be reduced

- The U.S. Supreme Court gets too mixed up in politics

- Justices who consistently make decisions at odds with what a majority of the people want should be removed

- The U.S. Supreme Court ought to be made less independent so that it listens a lot more to what the people want

- We ought to have a stronger means of controlling for actions of the U.S. Supreme Court

- The Court favors some groups more than others

Then, add all seven number together and divide by 7. This is your diffuse support score, on a scale from 1 (low support) to 5 (high support).

Perceived ideological distance

Respond to the following two items:

- Would you consider yourself very liberal (1), liberal (2), moderate (3), conservative (4), or very conservative (5)?

- Would you consider the U.S. Supreme Court very liberal (1), liberal (2), moderate (3), conservative (4), or very conservative (5)?

Then, subtract the two numbers and take the absolute value. This is your perceived ideological distance score, on a scale from 0 (no distance) to 4 (large distance).

As a class

Depending on the classroom size, the instructor could calculate the product moment correlation, or could graph each point to determine if there is a trend, or could otherwise summarize the data.

Discussion Questions

- The evidence suggests that a politician can influence public views of the judiciary when he or she criticizes the Court as a whole. Consider what might happen when a politician is critical of a particular decision the Supreme Court makes. Will it have the same influence? Now consider what might happen if a president who has nominated multiple justices criticizes the Court.

- Consider how famous an individual has to be before his or her statements about the judiciary can influence views of the Supreme Court. Can only the most notorious politicians—such as presidents, presidential candidates, or high-profile individuals—move views of the Court? Or can lower-profile individuals—such as governors, representatives, or members of the media—influence the public? Finally, consider the role of affect and partisanship for these lower-profile figures; do one’s feelings toward the figure matter more or less as they decrease in notoriety?

- Generally speaking, researchers consider two types of support for the judiciary. Specific support is job satisfaction, or support for a particular decision. Diffuse support is the (lack of) willingness to make lasting changes to the institution or decrease its independence. This chapter focuses on the diffuse variant, and I use the terms legitimacy, institutional support, and diffuse support interchangeably. ↵

- Data were collected using Amazon’s Mechanical Turk platform in October 2016 (Clinton experiment, N = 708) and November 2016 (Trump experiment, N = 503). ↵

- Note that agreement with these questions indicates a lack of legitimacy, or illegitimacy. So to measure legitimacy, I subtract each response from 6 to reverse the scale. For example, if somebody strongly agreed—a response of 5, the highest option possible—to a question, I merely subtract 5 from 6 so that score is now 1 (the lowest option possible, or a lack of legitimacy). ↵

- Importantly, these are general claims about the Court, but they do not focus on a particular decision. As such, we cannot determine how attacks on specific cases might influence the public. ↵

- It is important to consider that the effects of experimental treatments may fade as time passes. In other words, one’s assessment of the Court’s legitimacy may “bounce back” in the absence of reinforcing statements about the Court. However, as is noted here, criticisms of the judiciary and its decisions have increased in recent decades; reinforcing statements may not be as sparse as they once were. ↵