Actors in the Judicial Process

2 Examining Diversity, Inclusion, and Equity in the Legal Profession

An Analysis of Career Tracks and Representation

Scott Hofer and Susan Achury

Entering the legal profession in the United States has been viewed by many as a ticket to financial stability and a fulfilling career. Unfortunately, for most of American history, the profession, either through formal or informal barriers, has been largely off-limits to everyone except White men (Latourette 2004; Long 2016). While recent efforts to diversify the profession have successfully increased the presence of historically underrepresented groups, career outcome disparities take a long time to alleviate, and the legal profession is still significantly whiter and more male dominated than the American population as a whole (Long 2016). Data collection efforts have revealed some of the systemic obstacles for women and people of color (POC) to thrive in the legal profession; however, these analyses often explore different sectors of the legal profession separately—representation at private practices and on the bench. These analyses also oversimplify the concept of diversity, and few works have focused on assessing levels of inclusiveness and equity at all.[1] Identifying and measuring gaps in the participation of marginalized groups in the legal profession is key to designing and implementing policies that effectively shrink the gap.

In this chapter, we compare the gender and racial gaps in representation for private-practice careers versus careers in the federal courts. We advance the literature by examining these trends together rather than separately, which allows us to assess differences in career tracks. The diversity, inclusion, and equity framework helps us further explore diversification efforts, uncovering generalizable trends for women and POC. In particular, we highlight how this framework allows us to identify key obstacles to an equitable justice system. We compare the differences in representation of women and racial minorities in private practice and on the federal bench. We determine that diversifying the bench has proven more challenging. Overall, we point to the intervention of political actors in the nomination process and the effect of partisanship and ideological preference toward diversification might cause prolonged disparities in the court system.

Research Questions

Based on the Diversity, Inclusion, and Equity Framework, we compare the representation gap of women and POC in private practice with that on the federal bench. We offer a measurement of the underrepresentation of women and racial minorities in the legal profession and point out paths for future research:

- How diverse are the federal bench and private practice? Using diversification in law schools as a benchmark, we identify the gap in representation of women and POC within the entry-level positions.

- How inclusive are the federal bench and private practice? Given the lack of policies in law schools promoting equal access to different career paths, we measure the gap in advancement for women and POC from entry-level positions to the highest positions within their career tracks.

- How equitable are the federal bench and private practice?

Literature Review

To address our research questions with adequate appreciation of the obstacles facing underrepresented groups pursuing a legal career, we start by examining the Diversity, Inclusion, and Equity Framework (hereafter, DIE framework). This conceptual framework is then applied to past diversification trends, historic pioneers, and the early days of the profession in America. Next, we identify the extensive efforts to diversify the profession with a focus on law school admissions. Finally, we discuss the most common paths to a legal career and utilize the DIE framework to predict legal career outcomes.

The Importance of a Framework: Assessing Diversity, Inclusion, and Equity

The study of efforts to diversify the legal profession will necessitate a systematic method of analysis. Otherwise, anecdotes, platitudes, and rare examples may skew our perception of progress. While diversity itself is a commonly used term, its use often refers to multiple distinct concepts. To better address and assess efforts to add descriptive representation to the legal profession, we must start by delineating terms. We focus on three essential concepts in our framework: diversity, inclusion, and equity.

Diversity describes the entrance of women, racial minorities, and any other underrepresented demographic into the profession. It means that a wide variety of socially defined groups, perspectives, and experiences are involved. Diversity is the lowest standard for representation of marginalized groups because it is limited only to their presence. It marks the first step of entrance into the equation but little else. Although promoting diversity has improved access for underrepresented groups, this alone cannot correct disparities at the highest levels of the profession; additional corrective measures are necessary to enhance inclusion and equity. It is essential to provide conditions for people from diverse backgrounds to thrive in the profession to address disparities at the highest levels. Inclusion is the intermediate corrective action, which recognizes the need to construct an environment of support for underrepresented groups. While diversity opens the door for underrepresented groups within the profession, there are still significant barriers to success. Inclusion is a commitment to recognizing existing biases and making efforts to confront them. Implicit biases in the profession continue after employment begins, with minority associates being assigned lower-profile cases, given fewer support resources, and being less likely to make networking connections (Negowetti 2015). Without active efforts to promote inclusivity and understand the contributions to the profession among minoritized and marginalized groups, the status quo has been to discount their efforts when it comes time for promotions or advancement (Obasogie 2017).

Finally, the purpose of diversification and inclusion efforts is to gain equity in the profession. Equity is when the distribution of power, benefits, and burdens is not skewed by demographic factors, such as race and gender. When racial, gender, and demographic characteristics no longer skew the likelihood of reaching the pinnacles of success in a legal career, the profession can be called equitable. This represents a new status quo, in which discriminatory practices are so isolated, sporadic, and rare that they do not influence the overall balance of power. In an equitable profession, all socially defined groups are included proportionally to the population at all levels of power. The DIE framework advances our understanding of diversification efforts by distinguishing these higher and lower forms of descriptive representation. Without these distinctions, it is easy to conflate diversity in the ranks of law school students as equally crucial to equity at the highest levels of the legal profession. Now that we have identified a suitable framework for discussion, we will revisit some historical trends in diversification efforts.

Historic Diversity Trends in the American Legal Profession

Like much of American society, the legal profession, with few exceptions, was strictly segregated until the 1960s; this initial disparity has never been fully corrected (Moore 2007). During the early nineteenth century, the practice of law was a trade similar to most others. Rather than attending law schools, lawyers were taught through apprenticeships (Carp et al. 2019; Moliterno 1991; Gawalt 1973). As a result, many lawyers attained their jobs by following in the footsteps of their fathers. Once law schools replaced apprenticeships, they typically denied admittance to any applicant who was not White and male, effectively refusing diversity at its most fundamental level (Barnes 1970; Fossum 1981; Kidder 2003).

The story of racial diversity in the legal profession began in 1845 when Macon Allen became the first non-White lawyer licensed to practice in the United States. His license to practice law marked a major milestone at a time when slavery was still legal in the United States and racialized justice was the norm, not the exception (Smith 1993). Although formal barriers to the representation of racial minorities in the profession were technically broken, the impact was relatively minor, and the legal profession remains one of the whitest industries in America (Rhode 2013; Rhode and Ricca 2014; Wald 2011). Despite policies meant to promote diversity by hiring racial minorities, a pattern of higher attrition rates among legal professionals from underrepresented backgrounds illustrates a lack of an inclusive environment. Even overall racial diversity levels are striking low. As of 2017, roughly 13 percent of lawyers in the United States are not White; however, non-White residents of the United States make up nearly 40 percent of the population (Laffey and Ng 2018). Black Americans make up 13.3 percent of the population but only 5 percent of lawyers; Hispanic and Latino Americans make up 17.8 percent of the population but only 5 percent of the active attorneys in the United States (Laffey and Ng 2018). Although efforts have been made that did increase access to the profession, these disparities illustrate the barriers facing racial minorities in the legal profession (Laffey and Ng 2018).

Inclusion of women in the legal profession began when Arabella Mansfield was admitted to the Iowa Bar Association in 1869. Unfortunately, she was never given the opportunity to practice law (Chafa 2020). This trend of purely symbolic diversity continued in 1870, as Ada Kepley was admitted to law school but repeatedly denied in her attempts to practice law (Gorecki 1990). Women were systematically excluded from the profession by informal admittance processes in law schools and bar associations. Despite minuscule diversity levels, women still experienced discrimination in employment that effectively scuttled their hopes for successful careers (Krakauer and Chen 2003; Drachman 1989). Female lawyers began to make very modest inroads in diversity starting around the time of women’s suffrage (Bowman 2009). The first women admitted to the American Bar Association joined in 1918. However, female lawyers were an exception in the field of law even half a century later. By 1970, only 4 percent of America’s lawyers were female, and most of them were only in entry-level positions (Bowman 2009). Most progress in diversity levels for women has happened in the last fifty years, as women went from about 4 percent of the legal profession to 35 percent today (Bowman 2009; Laffey and Ng 2018). This was primarily the result of pioneering women who helped foster an environment of inclusion through female-oriented networking and programs to address the frequently hostile conditions (Kay and Wallace 2009; Kay and Gorman 2008).

Diversity progress has been significant and time dependent; however, inclusion is still lacking. Women make up almost 50 percent of summer associates[2] in the United States today but only 18 to 20 percent of lawyers in the highest echelons of legal practices—partners (Laffey and Ng 2018). There are several reasons for the continued lack of inclusion in the legal profession. One of the biggest is the exclusivity of social networks within the profession (Headworth et al. 2016; Fernandez and Fernandez-Mateo 2006; Rider et al. 2016). Success in law careers requires knowing the trade but also knowing some key actors with connections to lucrative jobs. The legal profession’s origins as an exclusive White and male industry in the United States created a homogenous network that has helped maintain the status quo through informal connections and implicit biases (Fernandez and Fernandez-Mateo 2006; Rider et al. 2016). Students at top law schools often benefit equally from the high-quality teaching at these institutions and the social networks created within the law school. The legal profession requires both hard skills—knowledge of the law—and soft skills, such as socializing and developing a clientele. Social networks are one way for employers to vet prospective employees for the necessary soft skills (Fernandez and Fernandez-Mateo 2006). Existing disparities mean those with the most power to hire or fire are predominately White and male. Ultimately, these exclusive trends are a significant factor in the higher rates of attrition for women and racial minorities in the profession (Rider et al. 2016).

Issues associated with homogeneity in the legal profession have been mainly addressed by looking at admissions processes to top law schools in the United States. America’s school districts remain highly racially segregated, and schools that primarily serve non-White communities are frequently underfunded (Rothstein 2015). As a result, students from predominantly non-White schools do not receive the same quality of primary and secondary school education and may settle for a lesser undergraduate education. The cascading effect occurs as students from lower-ranked undergraduate institutions are less appealing to the top law programs (Dowd 2015). Racial wealth disparity is further exacerbated by the high cost to attend law schools, which may serve as an insurmountable barrier for those at or below middle-class incomes (Harper and Griffin 2010). Societal-level disparities tend to impact all levels of education, but efforts to improve diversity in the profession tend to converge on the admissions process and financial aid resources available to law school applicants from underrepresented backgrounds (Jewel 2008; Rothstein and Yoon 2008; Kennedy 2019). By the 1970s, America’s top law schools began to actively promote diversity through different programs, including scholarships and reserving spots expressly to encourage gender and racial representation (Kennedy 2019; Jewel 2008). This marked the first step toward dramatic change, but it has been quite limited. Without thoroughly examining diversification and inclusiveness as different processes, one may not realize how progress with diversification still masks the disproportionate likelihood of female lawyers to hold low-seniority positions and less power in the profession (Kay and Gorman 2008).

Addressing the Diversity Problem: Affirmative Action and Beyond

Starting with Sweatt v. Painter 339 U.S. 629 (1950), which was cited in the influential Brown v. Board of Education 347 U.S. 483 (1954), the courts began to side with underrepresented minority groups who sought admissions to previously segregated schools (Kidder 2003). In the Sweatt case, Texas’s system of supposedly “separate but equal” law schools for black and White applicants was ruled unconstitutional. While Heman Marion Sweatt was begrudgingly admitted into the University of Texas Law School, by the mid-1960s civil rights legislation promoted efforts to either “boost” minority applicants or reserve spots in a “racetrack” system (Rothstein and Yoon 2008). In the years between Sweatt and the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the admissions process for universities, including law schools, went from efforts to discourage non-White applicants to a system that promoted diversity at some level (Sander 2004; Kennedy 2019).

Affirmative action programs faced significant backlash and were frequently undermined by university leadership; however, there is extensive evidence that these policies did promote diversity in legal training (Sander 2004; Rothstein and Yoon 2008). Legal challenges to the system of boosting or reserving seats for minority applicants occurred frequently, and over time, some ambitious programs were limited by legal actions.[3] The US Supreme Court struck down racial quota systems; however, it refused to strike down nonquota systems that sought to add diversity. Some universities incorporated nonracial ways to promote racial diversity by offering generous financial aid provisions for low-income and disproportionately non-White applicants (Sander 2004; Kennedy 2019).

There is strong evidence that these policies have promoted diversity in law schools. Rothstein and Yoon (2008) find that without affirmative action policies, nearly 60 percent of all black law school students would not have attended law school at all; meanwhile, at the top-tier law schools, there would be a nearly 90 percent decline in racial representation of black students if admissions were race blind (Kennedy 2019). Even after admission, informal barriers in the profession frequently limit future employment prospects as law students plan a career.

Law Career Tracks: Private Practice and Public Interest

While access is a necessary step toward a representative legal profession, granting such access to women and POC has been insufficient to achieve equity. Within the career tracks, essential differences between private practice or public interest careers have gone unexamined. As law students work toward graduation, they generally must choose a career path defined by this dichotomy.[4] These two career tracks have a great degree of variation in working conditions, pay, and promotion opportunities within the chosen track (Sander and Bambauer 2012). Still, some generalizations can be made. Typically, those who choose to work in private practice start as associates (entry-level positions) and eventually begin to own a part of their firm and be paid in profits as well as salary.[5] Reaching the equity partner level is no small accomplishment and represents one of the highest positions in private practice.

Law students who pursue the public interest path may take on entry-level positions as public defenders for the indigent; however, this position usually pays significantly less than entry-level positions at private firms (Bacak et al. 2020). The highest levels on the public interest career path are generally becoming an attorney general, state supreme court justice, or federal judge. These positions pay well but are especially appealing for the public esteem and security they provide. These careers are the result of a lifetime of public service and come with high opportunity costs. Advancing to appointment as a judge in any context is usually the high point in a public interest career. Efforts to diversify law school cohorts improved access to law schools; however, corresponding gains in the profession have been slow and not always incremental in both career paths.

Table 1 presents the participation percentage of women, POC, and women of color in the private sector and the federal bench compared to the US population and access and success in legal education in 2019. Data on the participation of women and POC in private practice is based on the annual report of the National Association for Law Placement (NALP) showing that representation of people of color in associate positions in private practices has continued to increase since 2010 (from 19.53 percent to 25.44 percent) following widespread layoffs in 2009. After a decade, the adverse effects of the 2008 economic crisis on diversification efforts have finally been reversed (NALP 2019). The percentage of African American female associates remains barely below the 2009 figure.[6] The 2008 financial crisis disproportionately hurt women and people of color in the profession, which illustrates that despite gains in diversity, there has been little progress made toward true equity in the profession. Efforts to diversify ranks have successfully added voices of color and women to entry-level positions, but once in these positions, there is often limited support and limited upward mobility (Kay et al. 2016; Payne-Pikus et al. 2010).

| Women (%) | POC (%) | Women of color (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benchmark | US population* | 50.75 | 31.3 | 18.8 |

| Supply | Law school enrollment

Law graduates** |

54

52.4 |

30.1

31 |

18.8

18 |

| Private practice | Entry-point at private practice (associate)***

Highest-point at private practice (equity partner)*** |

46.77

24.17 |

25.44

9.55 |

14.48

3.45 |

| Federal bench | Federal judiciary at the lowest point (district courts)****

Federal judiciary at the middle point (circuit courts)*** Federal judiciary at the highest point (Supreme Court)*** |

20.72

5.49 27.82 |

15.92

0.04 13.91 |

5.49

0.90 6.95 |

Table 1. Representation of women and POC in private practice and the federal bench (2019)

*Data from the US Census Bureu, Annual Estimates of the Resident Population by Sex, Race, and Hispanic Origin for the United States: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2019.

** Data from ABA Standard 509 Information Report Spreadsheets for 2019.

***Data from National Association for Law Placement, Report on Diversity in the US, 2019.

****Data from the Federal Judicial Center.

While trends in private practice are best viewed in the context of business, the diversification of the federal bench follows political procedures. The politics of promoting diversity on the bench may present greater barriers for women and POC. The impact of a single president on the composition of the bench can significantly increase representation. For example, the Obama administration made efforts to improve diversity; however, active steps to diversify the bench did not continue under the Trump administration. By July 2020, Trump had appointed a quarter of all the active federal judges; 25 percent were female, compared to 45 percent of Obama appointees. However, Trump appointed women at a rate similar to previous Republican presidents, drawing comparisons to the G. H. W. Bush administration (Jeknic et al., this volume). Meanwhile, only 18 percent of Trump’s appointments were non-White, compared to 36 percent of Obama appointees (Gramlich 2021). Trump did not share the same zeal for appointing diverse candidates to the federal bench and failed to increase diversity in the judiciary significantly; however, due to the preexisting lack of diversity in race and gender, Trump’s appointments have mostly just maintained the status quo in terms of the proportion of women and POC (see Jeknic et al., this volume).

Data and Methods

We use data from the US Census Bureau, American Bar Association, National Association for Law Placement, and the Federal Judicial Center to examine representation in entry-level positions all the way to the highest level in private practice, to compare it with the federal judiciary. We merge data as percentages to account for the differences in the size of the private practice and the federal judiciary and within each of these career paths.

Using the DIE framework to analyze gender and racial participation patterns in private practice, we analyze two categories: associate and equity partner. Diversity in private practice is measured as racial and gender representation as associates, the lowest ranks within the firms. For private practices, the hierarchy is designed for upward progression, so representation at the entry point (associate) signifies diversity, and inclusiveness is signified by the percentage of underrepresented groups moving up the hierarchy to equity partners. By analyzing differences between associates and equity partners, we can see the representation of women and POC in multiple stages of their careers.

In the federal judiciary we look into three levels: the district judges, the circuit, and the US Supreme Court. The implementation of the DIE framework is challenging in the judiciary, and we were only able to partially implement it due to data limitations. Diversity on the federal bench is difficult to identify, as judgeships are not considered entry-level positions for those working in the public sector. In this career track, positions such as clerks and public prosecutors, among others, are considered the starting point for progression into judgeships.[7] Measurements of diversity in public service should be assessed by looking at racial and gender demographics in the career choices of those aiming to get on the bench. Data limitations make it impossible to analyze the early career choices of those aiming to access the federal bench. Federal judgeships, regardless of the hierarchy, are a terminal stage in a legal career, a fact reinforced by the life tenure for all levels and little (Epstein et al. 2013). Thus racial and gender diversification of the bench is an indicator of inclusiveness, as it means that women and POC surmounted the structural biases against them and achieved a position of influence in the policy-making process.

The comparison between representation of women and POC in private practice and the federal judiciary uses diversity at law schools as a benchmark. Law schools determine the supply of diverse lawyers and to that extent their potential for a successful career. Admission marks the entrance into the legal profession; however, obstacles still await students from minoritized backgrounds. Improved access to legal training dramatically improved the diversity numbers at law schools, yet inclusion—the actions to support underrepresented students—is still lacking. Studies illustrate that focusing on law firm practice and partnership models to respond to advancement, attrition, and lack of re-engagement effectively achieves greater representation, particularly of women. An example of this is reassessing the competencies necessary to the success of law firms to value the work typically done by women (Seuffert et al. 2018). Frequently the labor of underrepresented groups is underappreciated or overlooked; meanwhile, this matter is made worse when combined with a lack of support or networking in the profession. Our analysis identifies inclusion as the percentage of racial minorities and women who progress in the legal profession beyond law school admissions to successful promotion in their chosen career track. For private practice, this means moving from an associate to a partner; meanwhile, in the public interest track, this means any position as a judge.

A comprehensive analysis of the cascade effect of exclusion and the glass ceiling, or the obstacles for advancement in legal careers, is needed to identify why the achievements for women and POC follow different patterns. This is an area of research that remains understudied and undertheorized. Pipeline explanations of gender and racial diversification of the legal profession have previously focused on the creation of a pool of “qualified” jurists (Cook 1984; Martin 1987). This approach has been challenged by empirical studies showing that access to legal education does not ensure similar gains in the participation of women and POC in the legal profession. For minority groups in the profession, equity would be an equal proportion of currently underrepresented groups at all positions of power in the profession. Since legal careers advance over time along a hierarchy in both tracks, equity can be measured by the proportion of partners in private practices and the proportion of federal judges. While there is still considerable work to be done in creating equity, our analysis will assess the current efforts goal (Polden and Teague 2020).

Results

A reconceptualization that differentiates between diversification and inclusiveness makes it possible to target specific barriers to equity in the legal profession and reveals undertheorized patterns of the process. Table 2 shows a snapshot of the representational gap of racial minorities and women in the legal profession in 2019.[8] First, notice that in terms of diversity in law schools, access is roughly proportional to the US population and the percentage of women in law school is 3 percent above their proportion of the national population. In terms of inclusiveness in law schools, we find that there is about a 5 percent difference between women and POC entering the program and those who completed it. However, the gap significantly increased in the transition from graduation to the early stages of legal careers; this difference becomes even more striking when comparing women and POC’s success in private practices with the federal bench. Accounting for this gap, further research should focus on identifying differences in the size of the gap within categories of law schools, especially since recent studies show that there is no longer a gap in terms of qualifications (Sen 2017). It is possible that top-tier schools are more successful at placing racial minorities and women into private practices than into the early stages toward judgeship. It could also be that economic disadvantages for joining a public career disproportionately affect women and POC.

| Representation gap across and within career paths | Women | POC | Women of Color |

|---|---|---|---|

| Equity gap in law school enrollment | -3.25 | 1.2 | 0.0 |

| Equity gap in law school enrollment | 5.63 | 5.56 | 0.8 |

| Gap between career paths (private associate vs district court) | 26.05 | 9.52 | 8.99 |

| Equity gap in the entry-point at private practice (private associate vs US population) | 3.98 | 5.86 | 4.32 |

| Equity gap in the federal judiciary at the lowest point (district courts vs. US population) | 30.03 | 25.44 | 14.48 |

Table 2. Measuring the gaps (2019)

In terms of the differences between women and POC, we find that women have achieved greater levels of representation than racial minorities in both the private and the public sectors. Even for women of color, the gap is smaller than for the aggregate of POC. The gap between the percentage of the population and the entry point in private practice is the smallest for women (3.98 percent) and the largest for POC (5.86 percent). A comparison between the early stages of women and POC in private practice and on the federal bench is currently impossible as we lack data on entry-level career choices that typically culminate in federal judgeships. But considering only clerkships at the US Supreme Court, we can see that the percentages of gender and racial representation are lower than those in private practice. For example, according to data from the National Law Journal, in 2017, only 5.5 percent of US Supreme Court clerks were POC, and only 25 percent were women (Mauro 2017). While these numbers reflect a significant increase compared to those reported in 2005, at both points in time the rates were lower than participation in private practices. So we find evidence that in terms of gender, race, and their intersection, the federal bench is less representative than private practice. Figure 1 presents the evolution of these patterns over time.

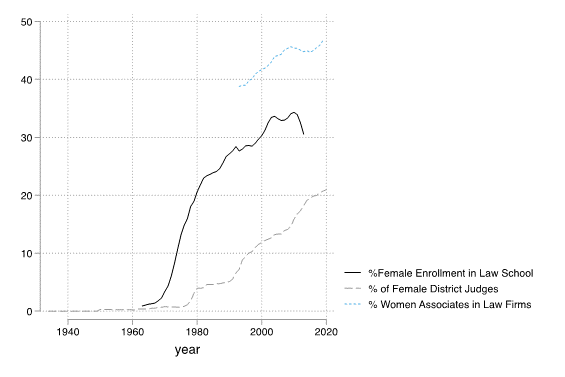

From a historical perspective, we find women are disproportionately participating in private practice rather than public service. For example, we see that while enrollment in law school was at its peak in the early 2000s (around 33 percent), about 46 percent of the private market was made up of women. In contrast, women accounted for only 13 percent of district judges. Also, we see that enrollment and private practices are more sensitive to economic crises such as in 2008, while female participation as district judges was not affected, due to lifetime tenure.

As the percentage of associate women in private firms is closer to parity, it is still necessary to make sure law schools address issues of gender equality that make it possible to create an opportunity for female legal professionals to achieve parity across different career choices. A paired t-test compares gender diversity using a sample of twenty-one years to determine whether there was a statistically significant mean difference between the percentage of women in law schools and the percentage of associate lawyers in private firms. There is a higher participation rate of women as associates (41.6 to 43.8 percent) as opposed to law students (30.3 to 32.4 percent): a statistically significant gap of 11.3 percent.[9] Notice also that inclusiveness in private practices shows that both the gender and the racial minority gap widen when we compare the entry position of associate to that of equity partner.

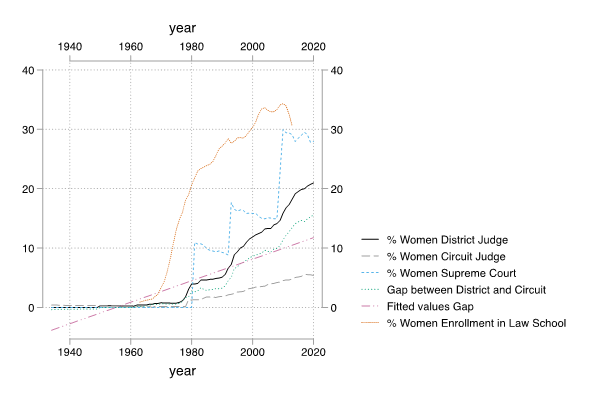

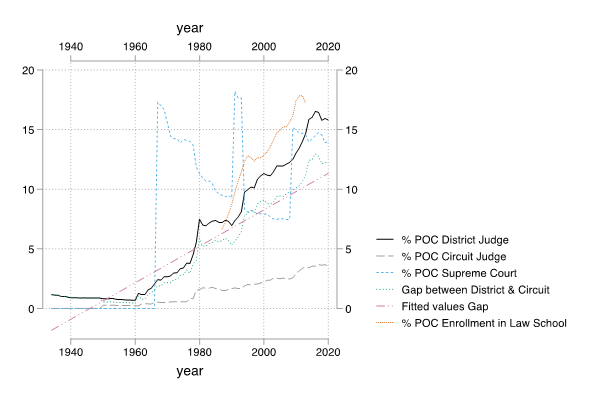

The most critical situation in terms of gender diversity is the exclusion of women in the federal judiciary. Figure 1 indicates a lag of almost twenty years between the beginning of female enrollment in law school and their inclusion in the federal district courts. While this trend can be in part explained by the inherent inertia of federal appointments—once there, they are there for life—it also exemplifies the need to develop policies that protect the diversity in private practices from economic factors. This is nicely illustrated with the economic crisis in 2008. It affected women in private practices, but it coincided with the beginning of the Obama administration, during which the largest number of women and people of color were appointed to the bench (Solberg and Diascro 2018). Different factors may explain this trend, including the role of political actors in determining the composition of the bench and the potential self-exclusion given the economic burden of the public interest path along with the additional uncertainty of advancement in this path. Evidence from the state supreme courts supports this claim. Racial and gender diversification of state supreme courts has been more successful where the political actors determine the composition of the bench via judicial appointments, as opposed to states where judicial elections determine the court’s composition (Robbins and Bannon 2019).

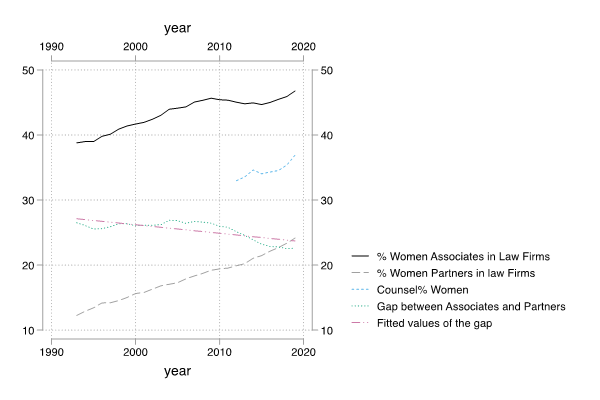

The lack of gender representation in the private sector is greater if we measure the gap between women in leadership roles versus associate or inferior roles. This approach is necessary for developing a perspective that can examine the conditions that make associate women less likely to be promoted than men. For example, in 2019, women accounted for 24.17 percent of partners, but just 1 in 5 equity partners were women (20.3 percent). Figure 2 illustrates the glass ceiling in private practice. Notice that the pace of improvement is slower at the top compared to the associate level. The difference between the percentages of female associates versus equity partners reveals that the gap has proven resilient. A modest and consistent improvement of about 2 percent reduction in this disparity has occurred during the last five years.

Meanwhile, the gap between female representation within firms as associates and partners remains steady at around 25 percent. This may introduce doubt about whether existing inclusion policies have been sufficient to increase representation in the highest positions of power in private practices. While gender equality at the lowest levels in private practice seems achievable in the near future, the lack of inclusiveness has reinforced the glass ceiling for women in this career path. Women remain severely underrepresented at the highest levels of power despite dramatic gains at the lowest levels of private practice.

Figure 3 shows differences in the level of inclusiveness achieved through the three levels of the federal bench. Since there is minimal mobility across the judicial hierarchy and judgeships are seen as the terminal position for the majority of the appointments, the gap between the levels may only reflect the willingness of the political actors involved in appointment and nomination to create spaces for women and POC. It relies on political actors pushing for marginalized groups to participate at the highest levels of the hierarchy, where they can have a greater influence on policy making and the possibility of social change. The gap across the levels of the hierarchy demonstrates that female participation is four times greater in district courts compared to the circuit courts. It also conveys that Democratic presidents have had more success in diversifying the composition of the highest court.

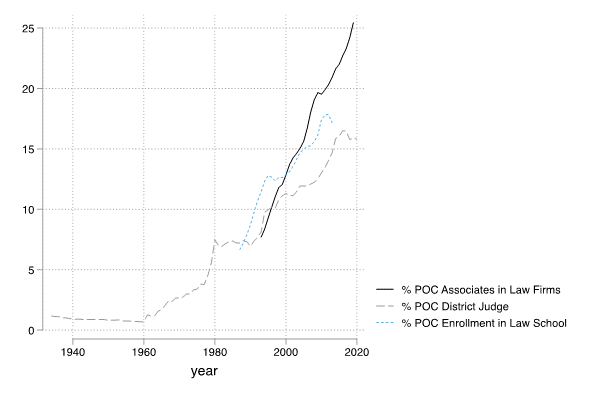

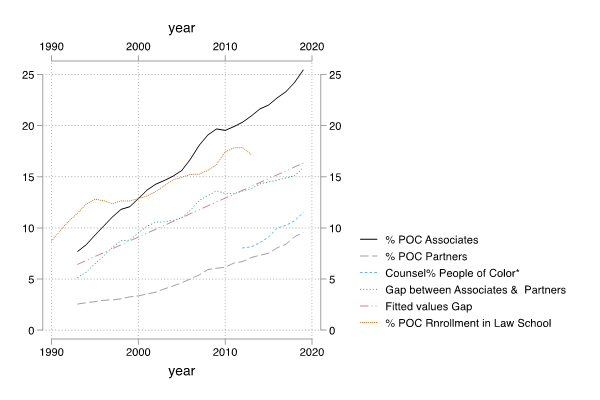

Patterns of racial diversification are similar to those of gender diversification; the representation of people of color in the private sector is closer to their population percentages than their representation in the federal court system. Estimates of population from the US Census (2010) suggest that men of color represent 19 percent and women of color, another 19 percent, of the total population.[10] The percentage of associates of color has been continuously increasing during the last decade, and today they represent about 25 percent of the entry positions in private firms. Interestingly, the percentage of minority enrollment in law schools is lower than the participation in private offices, which raises some questions about the system’s ability to create an adequate supply of attorneys of color.

When comparing gender diversification with racial diversification efforts, some differences are noteworthy. While the gender gap in law school enrollment has been declining since 2008, there is still a gap of 20 percent. For POC, there would need to be double the current rate of participation in law school to get to proportional representation. This is particularly troublesome as we see that enrollment in law school has declined across all minoritized groups, including women and POC.

Figure 4 shows that at the end of 1990, the ratio of representation of POC between the private sector and the federal bench was 1 to 1. Since then, the gap has grown immensely. Today, people of color are more represented in private practice than on the federal bench. The inability of political actors to keep up with the inclusiveness efforts of private firms may illustrate a failing of the political process to adequately recognize the accomplishments of attorneys of color. Further, it is also highly dependent on which party controls political institutions as Democrats have typically promoted more marginalized candidates to the bench than Republicans.

We find that the gap has actually increased in terms of the differences between POC associates and partners. Currently, the disparity is 10 percent greater than it was at the end of the 1990s. Figure 5 reveals an increase in the gap between representation at the entry level for jurists of color and partnership in private firms. It is clear that policies related to inclusiveness in private practices are needed in order to address the widening gap. Despite more well-trained attorneys of color than at any point in history, the problem of attrition and a lack of career progression for racial minorities has kept the highest positions of power disproportionately White.

Finally, figure 6 examines the relationship of power within the federal judicial hierarchy. Similar to the imbalances of power in private practice, within the judicial system, jurists of color are more likely to preside over the lower courts (district courts) rather than higher courts in the hierarchy. The racial gap on the federal bench is larger in the circuit than in the district court, where POC are represented three times more often. Similar to the case for women, the gap between district courts and the circuits has been widening over time. We also see that the percentage of minority enrollment in law school is higher than minority representation at any level of the bench. Despite significant efforts to close the qualification gap for racially minoritized people, the improved creƒdentials have not led to a correction of the disparity between people of color at the highest and lowest levels of the profession.

What Is Needed to Achieve Gender and Racial Equity?

After applying the DIE framework to measure the gaps in racial and gender representation in the legal profession, it becomes obvious that optimism about gains in descriptive representation may be naïve. While diversity itself is at or near all-time highs in almost every level of the profession, the gains have been primarily at entry-level positions or in law school enrollment; meanwhile, the rate of attrition for women and POC in the profession is disproportionately high, and promotions are disproportionately low (Kay et al. 2016; Payne-Pikus et al. 2010). The DIE framework allows us to put this trend into context as it distinguishes that diversity in the entry levels must be met with inclusiveness in order to eventually achieve equity.

Our analysis adds to the existing literature by comparing women and POC’s lack of representation throughout their careers across the hierarchies of private practice and the federal judiciary while differentiating between diversity, inclusion, and equity. We find that the increase in diversity for women and racial minorities between private practice and the federal bench has been uneven in terms of achievements and timing. While efforts to diversify law school cohorts have had a huge impact on the number of marginalized people entering private practices, this push has not resulted in immediate shifts in the inclusiveness of the profession and has only minimally moved the profession toward the ultimate goal of racial and gender equity. Through this lens, we uncovered the need for inclusiveness programs at early stages in legal careers, such as clerkships in law schools to promote women and racial minority representation on the bench. While recognizing the progress in terms of diversity, the need for improvements in inclusiveness to achieve equity is patent. The analysis presented in this chapter calls for further research on why diversification and inclusion efforts have been more successful for White women than for men and women of color.

Attempts to remedy the considerable disparities in the legal profession must first address huge disparities in the American education system and the current climate of unequal access to quality education. Law schools have been a focus for advocates of diversification; however, efforts by law schools focused exclusively on the admission process cannot solve the current racial and gender gaps at the top of the profession nor can they remove the existing barriers for marginalized groups in the profession. The pipeline to women and POC at the higher levels of the legal profession cannot exclusively rely on the creation of a pool of “qualified” jurists (Cook 1984; Martin 1987). Increased representation of marginalized communities in law schools is a move in the right direction. Without removing obstacles and providing adequate support systems for minoritized communities in the legal profession, attrition rates will still hamper attempts at racial and gender equity (Kay et al. 2016; Gorman and Kay 2010). That is to say, without real efforts to remove the barriers still in place in the legal profession, especially the informal barriers related to support structures and social networks, the larger goal of equity will remain out of reach.

References

Baćak, Valerio, Sarah E. Lageson, and Kathleen Powell. 2020. “‘Fighting the Good Fight’: Why Do Public Defenders Remain on the Job?” Criminal Justice Policy Review 31:939–61. (↵ Return)

Barnes, Janette. 1970. “Women and Entrance to the Legal Profession.” Journal of Legal Education 23:276–308. (↵ Return)

Bowman, Cynthia G. 2009. “Women in the Legal Profession from the 1920s to the 1970s: What Can We Learn from Their Experience about Law and Social Change.” Maine Law Review 61:1–25. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2) (↵ Return 3)

Carp, Robert A., Kenneth L. Manning, Lisa M. Holmes, and Ronald Stidham. 2019. Judicial Process in America. Washington, DC: CQ Press. (↵ Return)

Chafa, Emily. 2020. “Arabella ‘Belle’ Babb Mansfield: The First Woman Lawyer—Celebrating Her Legacy.” Judges’ Journal 59 (3): 22–24. (↵ Return)

Cook, Beverly B. 1984. “Women Judges: A Preface to Their History.” Golden Gate University Law Review 14:573. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Dowd, Alicia C., and Estela Mara Bensimon. 2015. Engaging the “Race Question”: Accountability and Equity in US Higher Education. New York: Teachers College Press. (↵ Return)

Drachman, Virginia G. 1989. “Women Lawyers and the Quest for Professional Identity in Late Nineteenth-Century America.” Michigan Law Review 88:2414. (↵ Return)

Epstein, Lee, William M. Landes, and Richard A. Posner. 2013. The Behavior of Federal Judges: A Theoretical and Empirical Study of Rational Choice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Fernandez, Roberto M., and Isabel Fernandez-Mateo. 2006. “Networks, Race, and Hiring.” American Sociological Review 71 (1): 42–71. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2) (↵ Return 3)

Fossum, Donna. 1981. “Women in the Legal Profession: A Progress Report.” American Bar Association Journal 67:578. (↵ Return)

Gawalt, Gerard W. 1973. “Massachusetts Legal Education in Transition, 1766–1840.” American Journal of Legal History 17 (1): 27–50. (↵ Return)

Gorecki, Meg. 1990. “Legal Pioneers: Four of Illinois’ First Women Lawyers.” Illinois Bar Journal (October 1990): 510–15. http://www.effinghamcountymuseum.org/sites/default/files/legal_pioneers_Ada_Kepley_at_Effingham.pdf. (↵ Return)

Gorman, Elizabeth H., and Fiona M. Kay. 2010. “Racial and Ethnic Minority Representation in Large US Law Firms.” In Special Issue Law Firms, Legal Culture, and Legal Practice, 211–38. Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing. (↵ Return)

Gramlich, J. 2021. “How Trump Compares with Other Recent Presidents in Appointing Federal Judges.” Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/01/13/how-trump-compares-with-other-recent-presidents-in-appointing-federal-judges/. (↵ Return)

Harper, Shaun R., and Kimberly A. Griffin. 2010. “Opportunity Beyond Affirmative Action: How Low-Income and Working-Class Black Male Achievers Access Highly Selective, High-Cost Colleges and Universities.” Harvard Journal of African American Public Policy 17:43–60. (↵ Return)

Headworth, Spencer, Robert L. Nelson, Ronit Dinovitzer, and David B. Wilkins. 2016. Diversity in Practice. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. (↵ Return)

Jewel, Lucille A. 2008. “Bourdieu and American Legal Education: How Law Schools Reproduce Social Stratification and Class Hierarchy.” Buffalo Law Review 56:1155. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Kay, Fiona, and Elizabeth Gorman. 2008. “Women in the Legal Profession.” Annual Review of Law and Social Science 4 (1): 299–2332. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Kay, Fiona M., and Jean E. Wallace. 2009. “Mentors as Social Capital: Gender, Mentors, and Career Rewards in Law Practice.” Sociological Inquiry 79 (4): 418–52. (↵ Return)

Kay, Fiona M., Stacey L. Alarie, and Jones K. Adjei. 2016. “Undermining Gender Equality: Female Attrition from Private Law Practice.” Law & Society Review 50 (3): 766–801. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2) (↵ Return 3)

Kennedy, Deseriee A. 2019. “Access Law Schools and Diversifying the Profession.” Temple Law Review 92:799. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2) (↵ Return 3) (↵ Return 4) (↵ Return 5)

Kidder, William C. 2003. “The Struggle for Access from Sweatt to Grutter: A History of African American, Latino, and American Indian Law School Admissions, 1950–2000.” Harvard BlackLetter Law Journal 19:1. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Krakauer, L., and C. P. Chen. 2003. “Gender Barriers in the Legal Profession: Implications for Career Development of Female Law Students.” Journal of Employment Counseling 40 (2): 65–79. (↵ Return)

Laffey, Allison, and Allison Ng. 2018. “Diversity and Inclusion in the Law: Challenges and Initiatives.” American Bar Association. https://www.americanbar.org/groups/litigation/committees/jiop/articles/2018/diversity-and-inclusion-in-the-law-challenges-and-initiatives/. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2) (↵ Return 3) (↵ Return 4) (↵ Return 5)

Latourette, Audrey Wolfson. 2004. “Sex Discrimination in the Legal Profession: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives.” Valparaiso Law Review 39:859. (↵ Return)

Long, Alex B. 2016. “Employment Discrimination in the Legal Profession: A Question of Ethics.” University of Illinois Law Review (2016): 445–86. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Martin, Elaine. 1987. “Gender and Judicial Selection: A Comparison of the Reagan and Carter Administration.” Judicature 71:136. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Mauro, Tony. 2017. “Mostly White and Male: Diversity Still Lags Among SCOTUS Law Clerks.” Law.com. https://www.law.com/nationallawjournal/sites/nationallawjournal/2017/12/11/mostly-white-and-male-diversity-still-lags-among-scotus-law-clerks/. (↵ Return)

McMillion, Barry J. 2014. US Circuit Court Judges: Profile of Professional Experiences Prior to Appointment. Congressional Research Service. https://library.law.uiowa.edu/sites/library.law.uiowa.edu/files/R43538.pdf. (↵ Return)

Moliterno, James E. 1991. “An Analysis of Ethics Teaching in Law Schools: Replacing Lost Benefits of the Apprentice System in the Academic Atmosphere.” University of Cincinnati Law Review 60:83. (↵ Return)

Moore, Wendy Leo. 2007. Reproducing Racism: White Space, Elite Law Schools, and Racial Inequality. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. (↵ Return)

NALP. 2019. NALP Report on Diversity in U.S. Law Firms 2019. https://www.nalp.org/reportondiversity. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Negowetti, Nicole. 2015. “Implicit Bias and the Legal Profession’s ‘Diversity Crisis’: A Call for Self-Reflection.” Nevada Law Journal 15 (2): 431–60. (↵ Return)

Obasogie, Osagie K. 2017. Review of “Diversity in Practice: Race, Gender, and Class in Legal and Professional Careers,” by Robert L. Nelson, Ronit Dinovitzer, David B. Wilkins. Contemporary Sociology 46 (6): 680–81. (↵ Return)

Payne-Pikus, Monique R., John Hagan, and Robert L. Nelson. 2010. “Experiencing Discrimination: Race and Retention in America’s Largest Law Firms.” Law & Society Review 44 (3–4): 553–84. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Pearce, Russell G., Eli Wald, and Swethaa S. Ballakrishnen. 2014. “Difference Blindness vs. Bias Awareness: Why Law Firms with the Best of Intentions Have Failed to Create Diverse Partnerships.” Fordham Law Review 83:2407. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Polden, Donald J., and Leah Jackson Teague. 2020. “More Diversity Requires More Inclusive Leaders Leading by Example in Law Organizations.” Hofstra Law Review 48:681. (↵ Return)

Randazzo, Sara. 2019. “Being a Law Firm Partner Was Once a Job for Life. That Culture Is All but Dead.” Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/being-a-law-firm-partner-was-once-a-job-for-life-that-culture-is-all-but-dead-11565362437/. (↵ Return)

Rhode, Deborah L. 2013. “Diversity and Gender Equality in Legal Practice.” University of Cincinnati Law Review 82:871. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Rhode, Deborah L., and Lucy Buford Ricca. 2014. “Diversity in the Legal Profession: Perspectives from Managing Partners and General Counsel.” Fordham Law Review 83:2483. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Rider, Christopher I., Adina D. Sterling, and David Tan. 2016. “Career Mobility and Racial Diversity in Law Firms.” In Diversity in Practice: Race, Gender, and Class in Legal and Professional Careers, edited by Spencer Headworth, Robert L. Nelson, Ronit Dinovitzer, and David B. Wilkins, 357–82. Cambridge Studies in Law and Society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2) (↵ Return 3)

Robbins, Laila, and Alicia Bannon. 2019. “State Supreme Court Diversity.” Brennan Center for Justice. https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/state-supreme-court-diversity. (↵ Return)

Rothstein, Jesse, and Albert Yoon. 2008. “Mismatch in Law School.” NBER Working Paper Series, Working Paper 14275, National Bureau of Economic Research. https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w14275/w14275.pdf. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2) (↵ Return 3) (↵ Return 4)

Rothstein, Richard. 2015. “The Racial Achievement Gap, Segregated Schools, and Segregated Neighborhoods: A Constitutional Insult.” Race and Social Problems 7 (1): 21–30. (↵ Return)

Sander, Richard H. 2004. “A Systemic Analysis of Affirmative Action in American Law Schools.” Stanford Law Review 57:367. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2) (↵ Return 3)

Sander, Richard, and Jane Bambauer. 2012. “The Secret of My Success: How Status, Eliteness, and School Performance Shape Legal Careers.” Journal of Empirical Legal Studies 9 (4): 893–930. (↵ Return)

Sen, Maya. 2017. “Diversity, Qualifications, and Ideology: How Female and Minority Judges Have Changed, or Not Changed, Over Time.” Wisconsin Law Review 2:367–99. (↵ Return)

Seuffert, Nan, Trish Mundy, and Susan Price. 2018. “Diversity Policies Meet the Competency Movement: Towards Reshaping Law Firm Partnership Models for the Future.” International Journal of the Legal Profession 25 (1): 31–65. (↵ Return)

Smith, J. Clay, Jr. 1993. “Justice and Jurisprudence and the Black Lawyer.” Notre Dame Law Review 69:1077. (↵ Return)

Solberg, Rorie Spill, and Jennifer Segal Diascro. 2018. “A Retrospective on Obama’s Judges: Diversity, Intersectionality, and Symbolic Representation.” Politics, Groups, and Identities 8 (3): 1–17. (↵ Return)

Sommerland, Hilary. 2014. “The Social Magic of Merit: Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in the English and Welsh Legal Profession.” Fordham Law Review 83:2325. (↵ Return 1) (↵ Return 2)

Wald, Eli. 2011. “A Primer on Diversity, Discrimination, and Equality in the Legal Profession or Who is Responsible for Pursuing Diversity and Why.” Georgetown Journal of Legal Ethics 24:1079. (↵ Return)

Understanding T-Tests

In the social sciences, researchers are always concerned that the results they find are occurring because of real-world causes rather than merely measurement error or random chance. For example, you could be an A (95 percent average) student but have a tough day and a lousy test—let’s say you score an 85 percent on this test. While the 85 percent result may not adequately describe your abilities as an A (95 percent) student, sometimes A students do not get As on their assignments or tests, but they still are A students nonetheless. In statistics, this is problematic, because taking an average of any given test for the whole class might not reflect the actual performance of the class, but rather that some students, for all sorts of reasons, did not perform as usual on their tests. Researchers need a way to determine the appropriate amount of confidence or trust that they can place in these results. For this reason, researchers use a concept called statistical significance. Statistical significance is a way to quantify how confident researchers are that the inferences they draw from their data illustrate some sort of effect rather than just random luck or circumstances. Generally, social scientists will declare their results to be statistically significant when they can be at least 95 percent confident that the results they are reporting are not simply due to random chance or error.

A t-test is one of the simplest ways to determine whether there are significantly significant differences between two groups. In this case, significant means the confidence we have that the differences between these two groups result from real differences and not just random chance. For example, let’s look at the average LSAT score for accepted students at Columbia Law School compared to the average LSAT score for accepted students at Harvard Law School. At Columbia, the average LSAT score is 172, and at Harvard, the average LSAT score is 173. At first glance, it is obvious that there is a difference between the two schools; however, Columbia students might argue that this metric doesn’t tell the whole story. The year (2019) for which this number was calculated might not be representative of all years. Or maybe by sheer random luck, a few Harvard students guessed and got correct answers, which skewed the statistics. In any measurement of group averages, in this case the average LSAT score, there is some amount of random chance. While Harvard is happy to advertise their higher scores on this metric, it is important to determine how sure we can be that this difference doesn’t reflect differences in random chance rather than actual real differences in performance. After all, students taking the LSAT might miss a question here and there for random reasons. How positive can we be about this difference between the scores? Is it fair to say that the difference is caused by Harvard having superior students?

How Does a T-Test Work?

When conducting a t-test, statisticians are concerned with three main concepts: absolute difference, standard deviation, and sample size. First is the amount of absolute difference between the two means. The absolute difference is simply how far apart the two groups’ averages are from one another. The reason for this is pretty obvious. If we are attempting to compare two groups by their LSAT scores and one group averages 150 while the other group averages 175, the large amount of difference between the two groups’ average (25 points) is a strong signal that there really is a cause (or than random chance) explaining the difference. In our previous example comparing Harvard and Columbia, the absolute difference is simply 173-172. An absolute difference of 1 point is much less likely to be significant than a 25-point difference, all things considered.

Second, we are concerned about the standard deviation of the group. Standard deviation is a measure of how much difference there is within each sample population. Using the Harvard versus Columbia example, the standard deviation would be the difference between accepted students within both schools. If there is a lot of variation within each sample, then we are not as confident that the difference between the samples is really the result of a cause. A wide variety of reported test scores in either class indicates that the means are less representative of the whole population. For example, if the range of test scores is 120–80 for Columbia, then the 172 average could be the result of outliers. Meanwhile, if there is a very small standard deviation, we can be more confident that there is a real difference. For example, if the test scores at Harvard range from 172 to 174, the average of 173 is not being determined by a few high scores or a few low scores; instead, it is being determined by a large number of test scores in the same range. As a result, the smaller the standard deviation between the two comparison groups, the higher the degree of certainty we can have in the results.

Finally, statisticians are always concerned with sample size. Sample size is simply the number of observations—in this case, test scores. In general, the larger the sample size, the more confident we can be about the resulting trends. For example, if we were to compare Harvard and Columbia, but one school’s average was based on only five LSAT scores while the other average was based on five thousand LSAT scores, we would be much more confident in the average generated from the larger sample. A sample with five thousand observations cannot be easily skewed by one or two outlier cases; meanwhile, a sample of five observations could change dramatically if only one or two test scores are very high or very low.

The Takeaway

T-tests are used to determine the amount of confidence that there is an actual difference between the two groups not caused by random chance. Whenever we compare group averages, there is a risk that some of the differences are caused simply by things like measurement error or random luck. For example, suppose we wanted to compare the performance of two different classes on the same test. In that case, there might be random things such as unclear questions, unusual attendance, grading errors, or other random events that do not tell us much about the actual performance. In groups, outliers or observations that are far from the norm can drive the averages for groups, especially in cases where the sample size is small. Statisticians use a t-test to assess how confident they can be that there is real difference between two groups rather than simply measurement error, random chance, outliers, or other forms of uncertainty.

Activity Questions

- True or False: It is possible to compare two groups based on their averages and assume that differences between the group averages are the result of real differences between the group populations with 100 percent certainty.

- True or False: Larger sample size increases the certainty that group-level statistics are adequately summarizing the information from the group rather than a few outliers.

- True or False: When comparing the averages of two different population groups, small variation within the groups (usually measured as standard deviation) will increase our confidence that there is a statistically significant difference.

- True or False: Researchers use the concept of statistical significance to determine how confident they are that their statistical inferences are determined by factors other than randomness, luck, or measurement/sample error.

- True or False: The typical level of confidence used to define statistical significance is 85 percent. It means that researchers are 85 percent confident that the results are not produced by random chance.

- See Sommerland (2014) in England using the DIE framework to assess the use of merit. In the US, see, e.g., Pearce, Wald, and Ballakrishnen (2014); Rhode and Ricca (2014). Notice all these works are focused exclusively on private practice. ↵

- See Sommerland (2014) in England using the DIE framework to assess the use of merit. In the US, see, e.g., Pearce, Wald, and Ballakrishnen (2014); Rhode and Ricca (2014). Notice all these works are focused exclusively on private practice. ↵

- Some famous cases dealing with these questions include Regents of Univ. of California v. Bakke, 438 US 265 (1978); Grutter v. Bollinger, 539 US 306 (2003); Hopwood v. University of Texas, 78 F.3d 932 (5th Cir. 1996); Podberesky v. Kirwan, 956 F.2d 52 (4th Cir. 1992); Johnson v. Board of Regents of Georgia 263 F.3d 1234 (11th Cir. 2001); and Gratz v. Bollinger 539 US 244 (2003). ↵

- While there are some examples of federal appointments of judges coming from private practices, this is not the most common path. Despite being an informal and nonexclusive process, there is a strong norm that law school students should choose a trajectory for their career based on one of these two tracks. ↵

- It should be noted that this career path appears to be rarer and rarer as the legal business norm moves away from this type of ownership model (Randazzo 2019). ↵

- One notable area of improvement in diversity since 2009 has been that LGBT lawyers have continuously risen and are the marginalized group with the highest representation among the summer associate ranks, where nearly 7 percent of all summer associates were reported as LGBT (NALP 2019). ↵

- This varies by president and level of court (Epstein et al. 2013). However, in the aggregate, it is possible to identify the patterns in terms of elite law school, clerking for a federal judge, and serving as a state judge or US attorney (McMillion 2014). Career changes from private practices to judgeship are often reserved to those at top-tier law firms. ↵

- Because the data are collected by different agencies using different methodologies, comparisons and the estimation of the differences across the stages in the legal career may include measurement errors. However, the numbers indicate patterns that should be further investigated with future data collection efforts. ↵

- Statistically significant at the 95 percent confidence level. The 95 percent confidence interval is 10.9 to 11.8 percent ↵

- This is considering any non-White person to be a person of color and is the broadest interpretation of the term, including Asian, Black, Hispanic, Native American and any multiracial person. ↵