Actors in the Judicial Process

5 Walking on Broken Glass

Justice Gender in State Supreme Court Citations

Shane A. Gleason; Scott A. Comparato; and Christine M. Bailey

State supreme courts sit at the apex of the state judiciary. While their decisions can be reviewed by the US Supreme Court in some issue areas, the decisions of state supreme courts are often final. State supreme courts’ importance has grown over the past forty years because of transformations of the social, legal, and political landscape resulting in tangible changes in the operation and perception of state supreme courts (Calderone, Canes-Wrone, and Clark 2009; Cann and Yates 2008; 2016). Interest groups are increasingly turning to state courts to pursue their policy goals (Kane 2017; 2018). Judicial elections are becoming more contentious and expensive (Bonneau and Hall 2009; Gibson 2012; Hall 2001; Kritzer 2007; Nelson, Caulfield, and Martin 2013). There has also been a precipitous rise in the professionalism—an aggregate measure of the salary and resources available—of many state courts, with changes in how they are organized and administered (Squire 2008). However, one of the most important differences is with the ability to alter the very content of case law is the identity of the jurists staffing state supreme courts.

In an era of rapid transformation on state supreme courts, one of the most visible shifts is to the immutable characteristics of the judges sitting on the bench. Far from the days when Florence Allen made history as the first female state supreme court justice in 1922 (Norgren 2018), women now constitute the majority of justices on ten state supreme courts (Ritter 2019). Particularly as scholars note that women bring a distinct perspective to judicial decision-making under certain conditions (e.g., Boyd, Epstein, and Martin 2010; Gleason, Jones, and McBean 2017; Haire and Moyer 2015), the inclusion of women on the bench could alter the substantive content of opinions. This could result in then judge Sonia Sotomayor’s suggestion that “a wise Latina woman with the richness of her experiences would more often than not reach a better conclusion than a white male who hasn’t lived that life” (Sotomayor 2002). In essence, Sotomayor suggests that lived experiences bring a distinct understanding to the law (see also: Boyd, Epstein, and Martin 2010; Glynn and Sen 2015). In this instance, that means an increasing number of women on a state supreme court results in a different kind of case law than that developed by a male justice.

While scholars hold that women bring a distinct voice to the legal process, the question then becomes, Where can we observe a distinct female voice in state supreme court opinions? Scholars have explored the role of judge gender in judicial behavior, albeit mostly at the federal level, in a number of different ways. Many scholars explore this through vote direction (e.g., Collins, Manning, and Carp 2010; Songer, Davis, and Haire 1994; Scheurer 2014; Boyd, Epstein, and Martin 2010; Gleason 2019; Szmer, Christensen, and Kaheny 2015). However, by focusing on the judge vote, these studies limit their analysis to the immediate case. This is problematic since we often care about decisions because of their impact beyond the case at hand. For instance, Roe v. Wade is often in the news because the core finding of that decision—namely, that the constitutional right to reproductive privacy is inclusive of abortion—shapes many subsequent decisions and the policy space available to legislatures. In other words, we care about Roe not because the Court split five to four, with Justice Brennan supporting Jane Roe and Justice Rehnquist supporting the State of Texas, but because it is a controlling precedent that shapes later decisions. To this end, had subsequent courts ignored Roe in the years after it was decided, we would likely not care very much about the decision today. Thus it makes sense for us to explore judicial impact through an analysis of how future courts respond to precedent.

Precedent can often be observed through citations. When an opinion is cited, it gives the author influence well beyond the immediate parties of the case at hand (Fowler and Jeon 2008) and shapes the options available to later courts deciding similar cases (Hansford and Spriggs 2006). It is important to distinguish that on state supreme courts, citations can come in two distinct forms: vertical and horizontal. When a justice writes an opinion, there are certain opinions that must be included. It would be exceptionally strange, for instance, for the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court to issue a ruling on marriage equality that does not reference Goodridge v. Department of Public Health, the case that made Massachusetts the first state to legalize same-sex marriage. In this instance, Goodridge is a vertical citation. It was decided by the Massachusetts court and is therefore a binding precedent for the state supreme court and its inferior courts. But the need to cite Goodridge changes if we shift our focus to the Illinois Supreme Court. For Illinois, Goodridge is not a binding precedent; any decision to cite it is entirely at the discretion of the Illinois court. These latter citations, termed horizontal citations because they occur between coequal courts, are where we focus for the rest of the chapter. Citing a decision horizontally is not legally required and thus represents the cited court choosing to allow the decision of the cited court to shape its own case law. We now turn to an overview of previous work on horizontal citations. We then develop expectations about how opinion author gender might shape horizontal citations before subsequently testing our expectations.

Explaining Citations

Citations spread between state supreme courts in much the same way that ideas about legislation spread between state legislatures. When Colorado and Washington implemented legalized recreational marijuana in 2012, several other state legislatures soon “copied” their approach. In brief, legislators learn from the experiences of other states and seek to emulate successful policies (Walker 1969; Berry and Berry 1990). State supreme courts likewise often turn to decisions made by peer courts rather than writing an opinion from scratch. Simply put, if another state supreme court has previously dealt with a legal issue, it makes little sense to “reinvent the wheel” when a court can draw on a persuasive and successful framework developed by a peer court (Shapiro 1965; 1970). Of course, state supreme courts will not copy just any legal argument. A number of scholars note that state supreme courts utilize citations from courts that resemble them in some way and those with reputations for producing high-quality opinions. To use the language of citation scholars, courts often horizontally cite proximate and prestigious peer courts. It is important to note that proximity and prestige have predicted horizontal citations for nearly a century, from Mott’s (1936) first study to the most contemporary update (Hinkle and Nelson 2016), despite considerable changes in the legal, political, and societal landscape (e.g., Fronk 2010). We now discuss proximity and prestige in turn.

Proximity follows the homophily principle; “birds of a feather flock together,” and courts cite courts that resemble them either ideologically or spatially. For instance, it is likely that the New York Court of Appeals and the California Supreme Court will cite each other, as they are both relatively liberal states. Indeed, Merryman (1954) notes that California cites New York the most of any of its peers. By the same logic, it is unlikely that Utah and Oregon will cite each other, as there is a large ideological gap between the two. States that are spatially proximate or in the same legal reporter region are also more likely to cite each other. In terms of geographic proximity, we would expect Ohio and Pennsylvania to cite each other often, as they are physically close to each other and likely deal with many of the same legal issues (Caldeira 1985). The decisions of state supreme courts are also published in legal reporting volumes that group states by region rather than reporting the decisions of each individual state in their own volume. As a result, courts that are in the same legal reporter region historically cite each other if only because they almost surely had each other’s opinions included in their law libraries. Of course, most legal research now takes place digitally rather than in physical books. While we might expect this effect to dampen the impact of reporter regions, they are still powerful predictors of horizontal citations in the twenty-first century (Hinkle and Nelson 2016).

Prestige also predicts horizontal citations. A prestigious court is one that other legal actors (courts) see as authoritative (e.g., Corley, Collins, and Calvin 2011). Importantly, as Mott puts it, “It is axiomatic that some supreme courts are more influential than others” (1936, 295). While all state supreme courts are technically equal, some states are seen as more prestigious by their peers and are thus cited more frequently. The reasons for prestige differences may be attributed to the nature of the cases that the courts hear, the expertise of the court, or the resources available.

Hearing diverse or novel cases can increase a court’s prestige. Caldeira (1983; 1985) finds that courts with more running feet of case law, higher state GDPs, and greater populations are more likely to be cited. Simply put, having more decisions results in a greater number of cases that can be cited horizontally. Hearing novel cases allows a court to increase its expertise in complicated areas of law that will then become attractive to other courts when they deal with these issues for the first time. For instance, the New Jersey Supreme Court is a leader in education finance decisions, partially because New Jersey was one of the first state supreme courts to deal with education finance and did so repeatedly. By necessity, New Jersey became a leader. When other courts were faced with education finance decisions of their own, it made sense to draw on the prestige New Jersey had developed in the area rather than creating a new decision from the ground up (e.g., Gleason and Howard 2015). Of course, if a court has a large body of case law and hears novel cases, it must still produce quality opinions that other courts want to cite. If a court has few resources, it will be hard-pressed to produce nuanced and persuasive opinions that other courts find attractive. A court with few resources likely has a heavy docket and little administrative support staff. As such, the opinions it produces generally lack nuanced legal reasoning. Those opinions will not be attractive to peers in other states. Conversely, one of the reasons the California Supreme Court is a network leader is because it has a discretionary docket and ample law clerk support to produce nuanced opinions (Hinkle and Nelson 2016; Squire 2008).

The literature on state supreme court citations demonstrates that citations are often the product of proximity and prestige. Importantly, however, this literature focuses on the primacy of courts over judges. This is problematic, as a core assumption of judicial behavior is that the identity of the judge shapes outcomes. For instance, the reason Justice Thomas often votes conservatively is because he is conservative (e.g., Segal and Spaeth 2002). By the same token, Justice Ginsburg is such an ardent supporter of women’s rights because of her lived experience as a female attorney who entered the legal profession in the 1950s (Haire and Moyer 2015; Norgren 2018). Likewise, the reason opinions by Chief Justice Marshall hold such sway two centuries after he wrote them is because of his stature as a jurist rather than the fact that the opinions were issued by the Supreme Court. Indeed, opinions written by Justice Washington, which we rarely see discussed, were also issued by the Supreme Court in the same era Chief Justice Marshall served.

While these are, to us, excellent reasons to add a judge-centric component to models of citation activity, the court-centric approach in state supreme court citation literature is likely driven by the sheer difficulty involved in obtaining information about state supreme court opinions in general and the justices who author them in particular. However, recent work by Hinkle and Nelson (2016) and Hall and Windett (2013) has ushered in a virtual treasure trove of data on state supreme court decisions and the justices who author them. In particular, Hinkle and Nelson (2016) provide information on every citation made by state supreme court justices in 2010, and Hall and Windett (2013) obtain case-level information, including the identity of the justice who authors the opinion, from 1994 to 2010. These data make it possible for scholars to move from exploring court-level explanations for horizontal citations to individual-level factors. However, in order to properly utilize these data, we need to formulate expectations about how justice-level factors shape citations.

Toward a More Identity-Based Account of Horizontal Citations

There is no existing work on how justice-level factors drive horizontal citations on state supreme courts, but there is literature on horizontal citations between federal appellate court judges. Just as state supreme courts often cite each other horizontally, so too do federal courts of appeals judges. Precedent handed down by the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals is binding on federal district courts within the Seventh Circuit (for instance, the Southern District of Illinois) and on the Seventh Circuit itself. It is often the case, though, that federal appellate court judges will cite their colleagues on other circuits. Importantly, this is a horizontal citation that is akin to a state supreme court citing a decision issued by a peer court in another state. Much like on state supreme courts, horizontal citations between federal appellate court judges are driven by proximity and prestige (Choi and Gulati, 2008; Landes, Lessig, and Solimine 1998; Anderson, 2011; Klein and Morrisroe, 1999; Cross, 2010). This literature typically looks at proximity and prestige in a manner that is fairly consistent with the literature on state supreme courts. Judges who are ideologically similar are more likely to cite each other. Indeed, the most ideologically extreme judges are less likely to be cited—likely because they are ideologically proximate to so few of their peers (Landes, Lessig, and Solimine 1998). Likewise, judges who have built up an extensive body of case law are more likely to be cited than freshman judges for the simple fact that the former have a larger body of work with which to build a prestigious reputation (Cross 2010). While this provides a dynamic foothold for extending state supreme court citation studies, we draw on recent work on diversity in the political realm generally and the legal sphere specifically, suggesting that immutable characteristics might drive the way judges evaluate their peers.

There are a number of different angles from which scholars could explore citations between state supreme court justices, including their lived experiences (Glynn and Sen 2015) and social contacts (Heinz et al. 1993). However, we choose to focus on immutable characteristics. Whereas life experiences can change with time and chance encounters or a faux pas can alter social interactions, immutable characteristics are more permanent. In particular, we focus on the role of opinion author gender in horizontal citations. Ample literature suggests that women experience the legal profession differently than their male peers (Haire and Moyer 2015; Gleason 2019; Gleason, Jones, and McBean 2017; Norgren 2018), and these experiences can determine which women ascend to the top of the legal profession (Baker 2003). Examining gender is all the more attractive considering the growing gender diversity of state judiciaries.

At a time when some of the earliest studies of citation patterns were appearing (see Mott 1936), female judges were exceptionally rare on state supreme courts. This would remain the case well into the late 20th century when others revisited the topic (see Caldeira 1983, 1985) but by the time the work of Hinkle and Nelson (2016) appeared, the state judiciary had become remarkably diverse. Female judges are now common on both state and federal benches (Szmer, Christensen, and Kaheny 2015; Slotnick, Schiavoni, and Goldman 2017). Indeed, they hold the majority in nearly 20 percent of all state supreme courts (Ritter 2019). Importantly, at all levels of the judiciary, female judges and bring a distinct voice that shapes case law and judicial behavior in subtle ways. For instance, Boyd (2016) finds that female judges are more likely to grant motions than their male counterparts. More germane to appellate court work, Songer, Haire, and Davis (1994) note that female judges decide more liberally in some issue areas. Importantly, Scheurer (2014) notes that female federal appellate court judges are more likely to take on a “different voice” after they reach a critical mass on a given bench (see also Collins, Manning, and Carp 2010). That is to say, when there are more women on a court, it is more likely that women’s distinct perspective will appear in decisions (e.g., Kenney 2002). This perspective can translate into the language used in the opinion (Gleason, Jones, and McBean 2017) and thus shape the range of options available to future courts adjudicating similar cases (Hansford and Spriggs 2006).

Scholars are increasingly cognizant of the role gender plays in political and legal outcomes. However, this literature presents somewhat mixed findings. While women are held to a double standard in political and social roles (Szmer, Sarver, and Kaheny 2010; Rhode 1994; Jones 2016; Gleason, Jones, and McBean 2017), women who ascend to the bench are generally seen as more qualified (Gill and Eugenis 2019; Pearson and McGhee 2013). This is perhaps because, in order to reach this level of the judiciary, female attorneys must truly excel in order to succeed in a male-dominated profession (Norgren 2018). Accounts of early female judges, both memoir based and scholarly, stress that women had a considerable uphill climb. By definition, those who did succeed were among the best justices (e.g., Abramson et al. 1977). Thus it is reasonable to expect that an opinion written by a female justice should be seen as more prestigious than one authored by a male justice.

Our proposition finds support in previous work on voters’ preferences for both male and female candidates. Voters do not hold female candidates to a different standard than male candidates or exhibit outright sexism. However, the traits that voters find desirable in candidates are less common among women (Teele et al 2018). Not surprisingly, then, women are less likely to run for office (Fox and Lawless 2005), but the average woman who does run is more qualified than the average male candidate (see Anzia and Berry 2011). Moreover, female candidates tend to be more sophisticated than their male counterparts (Niven et al 2019). However, women who run typically do so against more qualified candidates (Milyo and Schosberg 2000). Thus women are less likely to run for office, and those who do are more qualified and face stiffer competition. As such, women who make it into office are likely extremely qualified (e.g., Pearson and McGhee 2013). Voters appear to be aware of this, tending to prefer female state supreme court candidates under certain circumstances (Gill and Eugenis 2019).

Given that women face a more difficult path to office relative to their male counterparts (Teele, Kalaa, and Rosenbluth 2018), and those women who do become state supreme court justices are likely more qualified than their male counterparts (Pearson and McGhee 2013), it is possible that female justices’ peers see the opinions they author as more persuasive than those written by men. This would then increase the probability that their peers will view opinions written by female state supreme court justices as attractive horizontal citations. Accordingly, we expect that opinions authored by female state supreme court justices will be cited more frequently than those written by men.

Data and Methods

In order to explore the extent to which opinion author gender shapes the citation of state supreme court precedent, we combine two unique databases to measure the total number of times each justice who served between 1995 and 2010 is cited in 2010. Of course, with just one year of data, we are limited by how much we can generalize our findings. However, we feel that since there is no work on this topic, our work here represents an important first snapshot. We do so by drawing on previous data sets created by Hinkle and Nelson (2016) and Hall and Windett (2013). Hinkle and Nelson (2016) provide data on all citations made in the 2010 term, and Hall and Windett (2013) provide case-level information on all state supreme court decisions from 1994 to 2010. Importantly for our purposes, this includes the name of the opinion author. We augment these two databases with our own original research into the gender of all 727 justices who served on state supreme courts between 1995 and 2010.

Hinkle and Nelson (2016) use text-scraping software to extract every citation state supreme courts made in the 2010 term. Of course, the vast majority of these citations are vertical citations to a court’s own case law or that of its inferior courts. We drop these vertical citations and instead focus on just the horizontal citations for the reasons stated above. There are 1,897 horizontal citations made across all state supreme court opinions in 2010. But then the question becomes, Which justices are getting horizontally cited? Hinkle and Nelson’s (2016) data give us the citation information for each cited decision, but they do not tell us who wrote the opinion. Fortunately, we can use Hall and Windett’s (2013) data to supply the identity of the justice who wrote the cited opinion.

Hall and Windett’s (2013) data provide information on all 115,067 signed state supreme court decisions from 1995 to 2010. Using the case citation, which is common to both Hinkle and Nelson (2016) and Hall and Windett (2013), we are able to create a count for the total number of times each decision is cited. Of course, since we are primarily interested in the opinion author rather than the opinion itself, we then use the justice name variable in Hall and Windett (2013) to count the total number of times each of the 727 justices who served from 1995 to 2010 are cited in 2010.

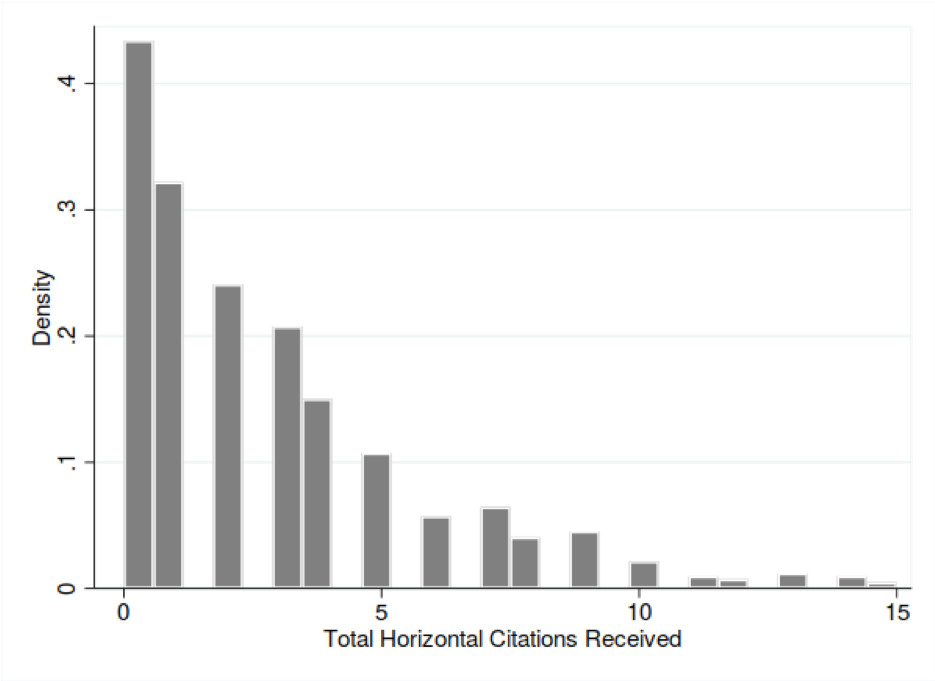

The total number of citations received by each justice constitutes our dependent variable. This count variable ranges from 0 to 15. Looking at the distribution of citations displayed in figure 1, it is clear that most judges receive no citations, whereas a relatively small number of justices receive a disproportionate share of horizontal citations. But since we are interested in knowing whether women are more likely to be cited, it is necessary to construct our primary dependent variable, which notes whether a given justice is male or female.

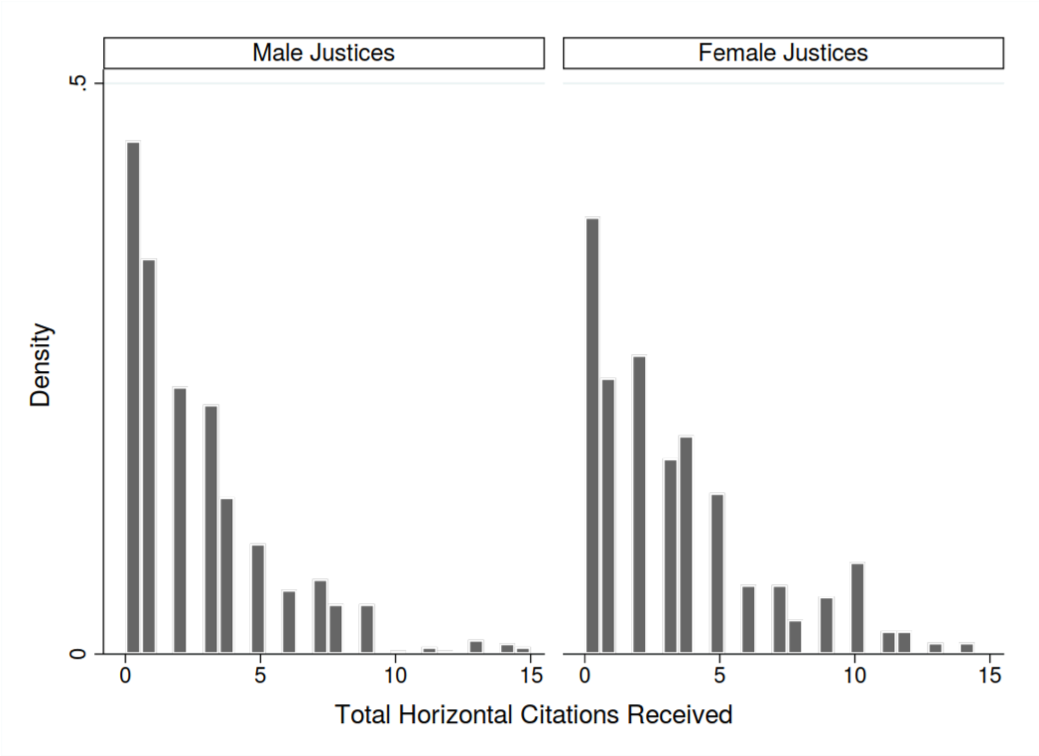

Our main independent variable is a binary measure of whether a given justice is male or female. To create this measure, we first use the Hall and Windett’s (2013) data to create a list of all state supreme court justices who served from 1995 to 2010. We then examine state supreme court websites and news accounts to determine whether a justice is male or female. We do so by looking for pronouns (e.g., “Justice X served on the law review during her time in law school” or “Justice Y and his family enjoy hiking”). The variable is coded 1 if a justice is female and 0 if a justice is male. After creating this measure, we rerun our histogram from figure 1, but this time we differentiate between male and female justices. This is displayed in figure 2. The left panel depicts citations to male justices; the right panel depicts citations to female justices. It appears that female justices are perhaps more likely to be cited than male justices. However, a visual inspection of a histogram can be deceiving. It could be that female justices in our data are cited more frequently by random chance. We address this possibility by running a t-test that measures whether a relationship (in this case, our observed propensity for female justices to be cited more than male justices) is due to random chance or a statistically significant difference. Our t-test confirms that female justices are more likely to be cited than male justices (p = 0.00).

While the histograms and t-test seem to support our contention that female justices are more likely to be cited horizontally than male justices, we must still account for existing explanations of proximity and prestige. A histogram merely models the distribution of data, and a t-test assesses for statistical significance between just two variables. Could it be that female justices are just more likely to serve on ideologically moderate courts? Or that male justices tend to be on courts with low resources? If either of those propositions is true, then the conclusions we drew are spurious, and the relationship we attributed to justice gender is actually a function of ideological proximity and professionalism prestige. Fortunately, we can follow the lead of Hinkle and Nelson (2016) and utilize a negative binomial regression model to explore whether female justices are more likely to be cited while accounting for existing explanations of proximity and prestige.

A negative binomial model resembles an ordinary least squares regression model, but it allows for the dependent variable to be a count (e.g., zero citations, one citation, eight citations) rather than a continuous measure as required by ordinary least squares models (e.g., −$20.03 in the bank, $115.67 in the bank). Of course, in order to run the negative binomial model, we need to specify control variables that account for the proximity and prestige explanations suggested by previous research. By including control variables, we ensure that we account for how proximity and prestige shape horizontal citations to state supreme court justices at the same time we test for whether female justices are cited more frequently than male justices.

We note proximity via a measure of state political ideology. That is to say, we expect state supreme courts to cite justices on courts that resemble their own ideologically. So we would expect Massachusetts to cite Illinois (both liberal states). We would not expect Illinois to cite Texas much (a conservative state). We create this measure via the Berry et al. (1998) state ideology scores. These scores create a measure from 0 (most conservative) to 100 (most liberal) at the state level. This allows us to move beyond simply calling a state liberal or conservative. This is a good thing, because while both Texas and Wyoming are conservative, Wyoming is a fair deal more conservative than Texas. Importantly, Berry et al. (1998) create scores for both the general public and government institutions. To illustrate this, in 2000 Illinois’ voters have a score of 54, which indicates that they lean slightly liberal. Illinois government institutions have a score of 40 in 2000, which demonstrates that they are considerably more conservative than the voters. Since state supreme court justices likely want to retain their jobs, we use the ideology score for the actor most responsible for the justices’ continued tenure. In states where justices are elected in some form, this is public ideology. For states where justices are appointed, this is elite ideology. We then calculate the state’s ideological distance from a purely moderate position (which would be 50 in the Berry et al. scores) by taking the absolute value of the state’s Berry et al. (1998) score for the state supreme court’s primary principal in the year the opinion was written. We expect that when the state issuing a decision is in a more ideologically extreme state, it will be less likely to receive citations, as it will be ideologically proximate to fewer peers (e.g., Cross 2010).

We include several measures of prestige. Chief among these is court professionalism. Simply put, a court that has ample resources will be able to produce nuanced opinions that are attractive to other state supreme courts. Much like Hinkle and Nelson (2016), we measure this with the index developed by Squire (2008). Prestige also comes from having specialized case law. Since hearing a diversity of cases enhances specialization, we note this in much the same way as Caldeira (1985) via the log of the state GDP and the population for the issuing court. The logic here is that states with higher GDPs will experience growth in their business sector, which leads to new and diverse litigation. Take, for instance, New York. Since New York is the home of Wall Street, it often hears new and innovative cases. So if New York hears a novel intellectual property case, other states will likely turn to that decision when they deal with similar topics later on. Much the same logic applies when a state’s population grows, as new questions about zoning, government services, and social interactions are likely to arise. Since numerous scholars note selection mechanism impacts eventual citation, as different selection mechanisms may attract different kinds of candidates (Fox and Lawless 2005) and thus perhaps change the way opinions are written (Caldeira 1985; Hinkle and Nelson 2016), we include a dichotomous measure noting whether the issuing court seats its members via popular election. This measure is set to 1 for elected courts and 0 otherwise. Since opinions have more opportunities to be cited over time, we include a count of a total number of years in which a judge’s decisions existed in the universe of cases. We do so by subtracting the first year a judge authored an opinion between 1995 and 2010 from 2010.

Results

Our results, presented in table 1, indicate that decisions written by women are more likely to be cited than decisions written by men. This provides support for our primary expectations. Additionally, some of our prestige control variables are significant. This demonstrates that while previous work utilizes proximity and prestige to explain horizontal citations, scholars must account for the gender of the justices being cited as well if they wish to arrive at a more complete understanding. We now turn to a detailed discussion of our results. Since negative binomial results are unintuitive, we discuss our results in terms of incident rate ratios.

| Variable | Coefficient | Standard Error |

|---|---|---|

| Female Justice | 0.221* | 0.081 |

| Court Ideology | -0/003 | 0/006 |

| Logged GDP | 1.320* | 0.249 |

| Logged Population | -1.426* | 0.284 |

| Court Professionalism | 0.100 | 0.492 |

| Elected Justice | -0.207*** | 0.111 |

| Years in Data | 0.102* | 0.009 |

| Contant | -4.052* | 1.094 |

| Alpha Coefficient | 0.597 | – |

| Observations | 727 | – |

| Chi 2 | 213.34 | – |

*:p=0.01, **: p=0.05, ***: p=0.10

Decisions written by women are more likely to be cited than those written by male justices. When a justice is female, the incident rate that she will be cited horizontally increases by 1.25, all else being equal. We also find that a one standard deviation increase in the state GDP increases the incident rate ratio for citation by 1.730, from 3.743 to 4.073. We note that as the population of the state increases, the probability that its decisions will be cited actually decreases. A one standard deviation increase in logged population decreases the incident rate of horizontal citation by 0.280, from 0.268 to 0.240. We also note that justices serving on elected courts are more likely to be cited. Serving on an elected court increases the incident rate of citation by 0.813 relative to appointed courts. Finally, each additional year a justice has opinions in our data set increases the incident rate of citation by 1.108.

Discussion

The stereotypical image of a judge is male. When women first entered the legal profession, they faced fierce pushback (Norgren 2018), and those who did ascend to the bench, by definition, had to be among the best (e.g., Abramson et al 1977; Haire and Moyer 2015). Now, slightly less than a century after Florence Allen became the first female state supreme court justice when she joined the Ohio Supreme Court in 1922, women increasingly occupy seats on state courts of last resort, and their opinions are cited horizontally more frequently than those authored by their male counterparts. This indicates that women are seen as more prestigious in the citation network. The literature from trailblazer women judges and women on the campaign trail suggests that this is because of the adversity female justices have to overcome to reach the bench (e.g., Norgren 2018; Haire and Moyer 2015). While we have answered the question we set out with, our results give rise to a number of new questions that should be explored more fully by future studies. We now turn to a brief overview of our findings and how future scholars might expand them.

We focus on horizontal citations because of their purely discretionary nature. Much of the literature on horizontal citations over the past eighty years finds that horizontal citations are the product of proximity and prestige. Importantly, however, we only find that prestige-based explanations are significant; ideology is not. Of course, we could argue that opinion author gender is a form of prestige. Still, the reasons why ideology is not significant are not entirely clear. It is possible, for instance, that the role of ideology is based not on the relative moderateness of the cited justice’s court but on the distance between the citing court and the cited court. By changing the specification of our model, future studies may be able to present a more nuanced explanation of how gender and ideology impact horizontal citations.

A key contribution of our approach is that unlike existing state supreme court horizontal citation studies, we include an individual-level factor in our model. Previous studies have relied almost exclusively on court-level factors, such as state ideology and professionalism. We include one judge-level factor, gender, and find that female justices are more likely to be cited than their male counterparts. What, though, of other individual-level factors, such as ideology, race, and accumulated body of case law? We opt to focus on just gender in this initial foray in order to keep our argument conceptually simple, but it stands to reason that if gender shapes citations, it is likely that other individual-level factors influence citations just as they do on federal appellate courts. Indeed, we think a comprehensive account of horizontal citations needs to consider the full range of court- and individual-level factors at the same time. We encourage future scholars to take up this project.

Perhaps one of the greatest limitations of our study here is that we do not know who is doing the citing because our dependent variable is a count of the total number of times each judge is cited. While we think this choice was justified in order to establish that female justices are cited more frequently than their male counterparts, there are reasons to believe that who cites is perhaps as important as who gets cited. To this end, Hinkle and Nelson (2016) note that federal appellate court judges tend to cite others from their in-groups. Could it be the case that most of the citations going to female justices are from other female justices? Particularly as evidence from the US Supreme Court indicates that women rely on a different calculus when evaluating legal information (Gleason, Jones, and McBean 2017), it is worth exploring what both ends of the citation dyad look like. This could be addressed with a dyadic model, as has often been the case in citation studies (e.g., Hinkle and Nelson 2016; Howard, Roch, and Schorpp 2017). This approach would also allow us to analyze characteristics of the case at hand, such as its salience or issue area.

Perhaps one of the greatest limits to our approach is the short time frame we employ. We explore horizontal citations made in 2010 to decisions authored between 1995 and 2009. While this approach is necessitated by the availability of data, it is important to recall the scope of available data is ever expanding, as are the statistical techniques available to researchers to explore the data. It was, after all, not that long ago that most state supreme court studies relied on the Brace, Langer, and Hall (2000) data, which in turn relied on a subsample of state supreme court cases decided between 1995 and 1999. As more data become available, we encourage future scholars to revisit this study with information from other years. In particular, it is worthwhile to look at a contemporary term such as 2019, where women hold majorities on nearly 20 percent of state supreme courts, alongside an earlier term from the 1980s or 1990s, where female justices were still relatively rare. Since a number of scholars note that female judges take on a different voice once they reach a critical mass in a given institutional context (Collins, Manning, and Carp 2010; Scheurer 2014), we suspect that the gendered context of state high courts will shape citation practices (e.g., Szmer, Christensen, and Kaheny 2015). Presumably as women occupy an increasing number of seats on a given court, the overall culture of the legal profession will become more inclusive (e.g., Kanter 1977; Kaheny, Szmer, and Sarver 2011; Kenney 2002). As such, the prestige of opinions written by women may dissipate. Of course, we leave it to future scholars to more fully explore this topic.

Finally, future scholars may gain leverage by looking at the role of gender in the opinion-writing process writ large. Murphy (1964) and Maltzman, Spriggs, and Wahlbeck (2000) note that opinion writing is the product of compromise and strategic behavior by the justices on the US Supreme Court. While we know the level of collegiality varies from one state supreme court to the next (Kritzer 2015), it is possible that a greater number of women on a given bench alters the extent to which bargaining and negotiating happens; this could extend to the horizontal citations chosen (e.g., Szmer, Christensen, and Kaheny 2015; Kaheny, Szmer, and Sarver 2011).

In this chapter, we explore horizontal citations on state supreme courts. While little has changed in scholarly accounts of horizontal citations over the past eighty years, we discuss how a relatively new feature of state benches, gender diversity, shapes horizontal citations. We find that female justices are more likely than their male peers to be cited horizontally. This is consistent with existing work that reveals that women who secure high political offices are often more qualified than men in those institutions. While our results here are exciting, they pose a number of new questions for future scholars to explore more fully.

Learning Activity

- What is precedent? How is precedent transferred throughout the court system? How do justices choose which precedent to use and which precedent to ignore when crafting opinions?

- What is the relative merit of horizontal citations? Are there any problems with a state supreme court turning to a court or justice that is in no way accountable to the voters in the citing state? Why should any state turn to another state for citations when the only court that has legal authority over them is the US Supreme Court?

- The authors find that women are cited more frequently because of the difficult path to the bench they experience. Can you think of any other institutions (political or otherwise) or social interactions where this might be the case? Might this effect manifest with different identities beyond gender?

- The chapter discusses gender-based differences (in both experience and treatment) of women in legal and political professions. Provide an example of a gender-based difference of a female attorney. Provide an example of a gender-based difference of a female politician.

- What is judicial prestige? What factors contribute to judicial prestige? How might this effect horizontal citations?

- What is judicial proximity? Why might a court or a judge want to cite someone “like them” in horizontal citations? Where else might we see this in judicial behavior or political science writ large?

- Analysis of the data revealed that very few of the cases that are generated by the courts every year eventually become horizontal citations. Does gender play a role when a justice decides to use a horizontal citation? Do you suppose the justices are intentionally choosing to cite opinions crafted by women or might this operate at a more subconscious level?

- The authors used male and female pronouns on state websites in order to code for the justice’s gender. Is this the best way to establish the gender of a state supreme court judge? Are there any potential problems with coding a justice’s gender in this manner? Why do you suppose the authors opted for this approach?

- What are Berry et al. scores? How did the authors use these scores in their analysis? Is this the most effective way to measure state political ideology? Can you think of other ways to measure state political ideology?

- While the results of statistical models are the same no matter who puts them together, the structure of the model may be different based on who is building it. Two of the three authors are men. Both Gleason and Comparato are men. Bailey is a woman. Is it possible that the authors’ lived experiences of gender shaped the research question and the structure of the chapter? How might this chapter have been different if all three authors were men? If two of the three authors were women? If all of the authors were women? Gleason, a male, specializes in gender-based court research. Does this change your evaluation of the study?

References

Abramson, Paul R., Philip A. Goldberg, Judith H. Greenberg, and Linda M Abramson. 1977. “The Talking Platypus Phenomenon: Competency Ratings as a Function of Sex and Professional Status.” Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2 (2): 114–124.

Anderson, Robert. 2011. “Distinguishing Judges: An Empirical Ranking of Judicial Quality in the United States Courts of Appeals.” Missouri Law Review. 76 (2): 315–383.

Anzia, Sarah F., and Christopher R. Berry. 2011. “The Jackie (and Jill) Robinson Effect: Why Do Congresswomen Outperform Congressmen?” American Journal of Political Science. 55 (3): 478–493.

Baker, Joe G. 2003. “Glass Ceilings or Sticky Floors?: A Model of High-Income Law Graduates.” Journal of Labor Research. 24 (4): 695–711.

Berry, Frances Stokes, and William D. Berry. 1990. “State Lottery Adoptions as Policy Innovations: An Event History Analysis.” American Political Science Review. 84 (2): 395–415.

Berry, William D., Evan J. Ringquist, Richard C. Fording, and Russell L. Hanson. 1998. “Measuring Citizen and Government Ideology in the American States, 1960–93.” American Journal of Political Science. 41: 327–348.

Bonneau, Chris W., and Melinda Gann-Hall. 2010. “‘The Battle Over Judicial Elections: Right Argument, Missed Audience’: A Response to Stephen Wasby.” Justice System Journal. 31 (1): 117–120.

Boyd, Christina L., Lee Epstein, and Andrew D. Martin. 2010. “Untangling the Causal Effects of Sex on Judging.” American Journal of Political Science. 54: 389–411.

Boyd, Christina L. 2016. “Representation on the Courts? The Effects of Trial Judges’ Sex and Race.” Political Research Quarterly. 69: 788–799.

Brace, Paul, Laura Langer, and Melinda Gann-Hall. 2000. “Measuring the Preferences of State Supreme Court Judges.” Journal of Politics. 62 (2): 387–413.

Caldarone, Richard P., Brandice Canes-Wrone, and Tom S. Clark. 2009. “Partisan Labels and Democratic Accountability: An Analysis of State Supreme Court Abortion Decisions.” Journal of Politics. 71: 560–73.

Caldeira, Gregory A. 1983. “On the Reputation of State Supreme Courts.” Political Behavior. 5: 83–108.

———. 1985. “The Transmission of Legal Precedent: A Study of State Supreme Courts.” American Political Science Review. 79: 178–194.

Cann, Damon M., and Jeff Yates. 2008. “Homegrown Institutional Legitimacy Assessing Citizens’ Diffuse Support for State Courts.” American Politics Research. 36 (2): 297–329.

———. 2016. These Estimable Courts: Understanding Public Perceptions of State Judicial Institutions and Legal Policy‐Making. New York: Oxford University Press.

Choi, Stephen J., and G. Mitu Gulati. 2008. “Bias in Judicial Citations: A Window into the Behavior of Judges?” The Journal of Legal Studies. 37: 87–130.

Collins, Paul. M., Kenneth L. Manning, and Robert A. Carp. 2010. “Gender, Critical Mass, and Judicial Decision Making.” Law & Policy. 32 (2): 260–281.

Corley, Pamela C., Paul M. Collins, and Bryan Calvin. 2011. “Lower Court Influence on U.S. Supreme Court Opinion Content.” The Journal of Politics. 73 (1): 31–44.

Cross, Frank B. 2010. “Determinants of Citations to Supreme Court Opinions and the Remarkable Influence of Justice Scalia.” Supreme Court Economic Review. 18 (1): 177–202.

Fowler, James. H., and Sangick Jeon. 2008. “The Authority of Supreme Court Precedent.” Social Networks. 30: 16–30.

Fox, Richard L., and Jennifer L. Lawless. 2005. “To Run or Not to Run for Office: Explaining Nascent Political Ambition.” American Journal of Political Science. 49: 642–659.

Fronk, Casey. R. 2010. “The Cost of Judicial Citation: An Empirical Investigation of Citation Practices in the Federal Appellate Courts.” Journal of Law, Technology, & Policy. 1: 51–90.

Gibson, James L. 2012. Electing Judges: The Surprising Effects of Campaigning on Judicial Legitimacy. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Gill, Rebecca, and Kate Eugenis. 2019. “Do Voters Prefer Women Judges?: Deconstructing the Competitive Advantage in State Supreme Court Elections.” State Politics and Policy Quarterly.

Gleason, Shane A. 2019a. “Beyond Mere Presence: Gender Norms in Oral Arguments at the U.S. Supreme Court.” Political Research Quarterly. XX: 1–13.

Gleason, Shane A, and Robert M. Howard. 2015. “State Supreme Courts and Shared Networking: The Diffusion of Education Policy.” The Albany Law Review. 78 (4): 1485–1511.

Gleason, Shane A., Jennifer J. Jones, and Jessica Rae McBean. 2017. “Gender Performance in Party Brief Success.” Washington University Journal of Law and Policy. 54: 89–99.

Glynn, Adam N., and Maya Sen. 2015. “Identifying Judicial Empathy: Does Having Daughters Cause Judges to Rule for Women’s Issues.” American Journal of Political Science. 59: 37–54.

Hall, Matthew E. K., and Jason H. Windett. 2013. “New Data on State Supreme Court Cases.” State Politics and Policy Quarterly. 13 (4): 427–445.

Hall, Melinda Gann. 2001. “State Supreme Courts in American Democracy: Probing the Myths of Judicial Reform.” American Political Science Review. 95 (2): 315–330.

Haire, Susan B., and Laura P. Moyer. 2015. Diversity Matters: Judicial Policy Making in the U.S. Courts of Appeals. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press.

Hansford, Thomas, and James F. Spriggs II. 2006. The Politics of Precedent on the U.S. Supreme Court. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Heinz, John P., Edward O. Laumann, Robert L. Nelson, and Robert H. Salisbury. 1993. The Hollow Core: Private Interests in National Policy Making. Cambridge, MA. Harvard University Press.

Hinkle, Rachel K., and Michael J. Nelson. 2016. “The Transmission of Legal Precedent Among State Supreme Courts in the 21st Century.” State Politics & Policy Quarterly. 16 (4): 391–410.

Howard, Robert M., Christine H. Roch, and Susanne Schorpp. 2017. “The Diffusion of the Constitution: Emulation and Adoption of State Court Ordered Education Finance.” Law and Policy. 39 (2): 142–169.

Jones, Jennifer J. 2016. “Talk ‘Like a Man’: The Linguistic Styles of Hillary Clinton, 1992-2013.” Perspectives on Politics. 14: 625–642.

Kaheny, Erin B., John J. Szmer, and Tammy A. Sarver. 2011. “Women Lawyers Before the Supreme Court of Canada.” Canadian Journal of Political Science. 44 (1): 83–109.

Kane, Jenna Becker. 2017. “Lobbying Justice(s)?: Exploring the Nature of Amici Influence in State Supreme Court Decision Making.” State Politics and Policy Quarterly. 17 (3): 251–274.

———. 2018. “Informational Need, Institutional Capacity, and Court Receptivity: Interest Groups and Amicus Curiae in State High Courts.” Political Research Quarterly. 71 (1): 881–894.

Kanter, Rosabeth Moss. 1977. “Some Effects of Proportions on Group Life: Skewed Sex Ratios and Response to Token Women.” American Journal of Sociology. 82 (5): 965–990.

Kenney, Sally J. 2002. “Breaking the Silence: Gender Mainstreaming and the Composition of the European Court of Justice.” Feminist Legal Studies. 10: 257–270.

Klein, David, and Darby Morrisroe. 1999. “The Prestige and Influence of Individual Judges on the U.S. Courts of Appeals.” Journal of Legal Studies. 28: 371–391.

Kritzer, Herbert M. 2007. “Law is the Mere Continuation of Politics by Different Means: American Judicial Selection in the Twenty-First Century.” DePaul Law Review. 56: 423–68.

———. 2015. Justices on the Ballot: Continuity and Change In State Supreme Court Elections. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Landes, William M., Lawrence L. Lessig, and Michael E. Solimine. 1998. “Judicial Influence: A Citation Analysis of Federal Courts of Appeals Judges.” The Journal of Legal Studies. 27 (2): 271–332.

Maltzman, Forrest, James F. Spriggs II, and Paul J. Wahlbeck. 2000. Crafting Law on the Supreme Court: The Collegial Game. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Merryman, John Henry. 1954. “The Authority of Authority: What the California Supreme Court Cited in 1950.” Stanford Law Review. 6 (4): 613–673.

Milyo, Jeffrey, and Samantha Schosberg. 2000. “Gender Bias and Selection Bias in House Elections.” Public Choice. 105 (1–2): 41–59.

Mott, Rodney. 1936. “Judicial Influence.” American Political Science Review. 30: 295–315.

Murphy, Walter F. 1964. Elements of Judicial Strategy. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Nelson, Michael J., Rachel Paine Caufield, and Andrew D. Martin. 2013. “OH, MI: A Note on Empirical Examinations of Judicial Elections.” State Politics and Policy Quarterly. 13 (4): 495–511.

Niven, David, Alexis Straka, and Anwar Mhajne. 2019. “Who Reveals, Who Conceals?: Candidate Gender and Policy Transparency.” Political Research Quarterly. XX: 1–13.

Norgren, Jill. 2018. Stories from Trailblazing Women Lawyers. New York: New York University Press.

Pearson, Kathryn, and Erin McGhee. 2013. “What it Takes to Win: Questioning ‘Gender Neutral’ Outcomes in U.S. House Elections.” Politics and Gender. 9 (4): 439–462.

Rhode, David L. 1994. “Gender and Professional Roles.” Fordham Law Review. 63: 39–72.

Ritter, Ken. 2019. “Nevada Joins States With Female Majority on High Court.” The Associated Press. January 11. https://www.apnews.com/28940d6ef89f4b01af62a800a85d94bd

Scheurer, Katherine Felix. 2014. “Gender and Voting Decisions in the U.S. Court of Appeals: Testing Critical Mass Theory.” Journal of Women, Politics, & Policy. 35: 31–54.

Segal, Jeffrey A., and Harold J. Spaeth, H. 2002. The Supreme Court and the Attitudinal Model Revisited. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Shapiro, Martin. 1965. “Stability and Change in Judicial Decision-Making: Incrementalism or Stare Decisis?” Law in Transition Quarterly. 2: 134–157.

———. 1970. “Decentralized Decision-Making in the Law of Torts.” In Political Decision-Making, ed. Sydney S. Ulmer, 44–75. New York: Van Nostrand.

Slotnick, Eliot, Sara Schiavoni, and Sheldon Goldman. 2017. “Obama’s Judicial Legacy.” Journal of Law and Courts. 5 (2): 363–422.

Songer, Donald R., Sue Davis, and Susan Haire. 1994. “A Reappraisal of Diversification in the Federal Courts: Gender Effects in the Courts of Appeals.” Journal of Politics. 56 (2): 425–439.

Sotomayor, Sonia. 2002. “A Latina Judge’s Voice.” Berkeley La Raza Law Journal. 13 (1): 87–94.

Squire, Peverill. 2008. “Measuring the Professionalism of State Courts of Last Resort.” State Politics and Policy Quarterly. 8 (3): 223–238.

Szmer, John J., Tammy A. Sarver, Erin B. Kaheny. 2010. “Have We Come a Long Way, Baby?: The Influence of Attorney Gender on Supreme Court Decision Making.” Politics & Gender. 6: 1–36.

Szmer, John, Robert K. Christensen, and Erin B. Kaheny. 2015. “Gender, Race, and Dissensus on State Supreme Courts.” Social Science Quarterly. 96: 553–575.

Teele, Dawn. L., Joshua Kalaa, and Frances McCall Rosenbluth. 2018. “The Ties that Bind: Social Roles and Women’s Underrepresentation in Politics.” American Political Science Review. 112 (3): 525–541.

Walker, Jack W. Jr. 1969. “The Diffusion of Innovations among the American States.” American Political Science Review. 63: 880–99.

Further Reading

Gleason, Shane A. 2019b. “The Role of Gender Norms in Judicial-Decision-Making at the U.S. Supreme Court: The Case of Male & Female Justices.” American Politics Research. 47 (3): 494–529.