Actors in the Judicial Process

10 The Conservative Ideological Drift of Federalist Society-Associated Justices

Peter S. K. Lynch

Introduction

The Federalist Society is a network of conservative and libertarian attorneys, judges, law professors, and law students. Since the network’s founding in 1982, it has come to play a decisive role in the United States’ legal system. The network not only shapes how conservative legal scholars think about the law and jurisprudence but also has dramatically affected the ideological composition of the courts through successful nominations of its members to the federal (and state) courts. The network has been especially successful at promoting its members to the US Supreme Court.

The network’s first affiliate to join the Supreme Court was Antonin Scalia, who was confirmed in 1986 and had previously served as the first faculty adviser for the University of Chicago’s chapter of the Federalist Society. Since the confirmation of Scalia, seven of the nine nominees confirmed to the Supreme Court during Republican presidencies have been affiliated with the Federalist Society. In fact, the last time a Republican president confirmed a nominee who was not affiliated with the Federalist Society was in 1990, when George H. Bush nominee David Souter was confirmed to the Court. Since then, all six justices confirmed to the Supreme Court under Republican administrations have been affiliated with the Federalist Society. While the organization and its influence within judicial politics went largely unnoticed for several decades, the network gained widespread public attention during the Trump administration. Since the confirmation of Justice Kavanaugh in 2018, Federalist Society–affiliated justices have held a majority of seats on the Court. With the confirmation of Justice Barrett in 2020, Federalist Society–affiliated justices now occupy six of the nine seats on the Supreme Court. From their position at the top of the judicial hierarchy, Federalist Society–affiliated justices now have control over which petitions for writ of certiorari the Court will reject, which cases it will accept, and how those cases will be decided.

In sum, justices affiliated with the Federalist Society have control over both the Supreme Court’s docket and the decisions that the Supreme Court makes. This influence can be seen in recent cases such as Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization (2022) and Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard University (2023)—two cases in which the Supreme Court overruled landmark precedents concerning abortion (Roe v. Wade) and affirmative action (Grutter v. Bollinger).

Although justices affiliated with the Federalist Society effectively control the Supreme Court, there is surprisingly little quantitative research on judges affiliated with the Federalist Society or what distinguishes them from other Republican-nominated justices. For the purposes of this study, justices associated with the Federalist Society will be hereafter referred to as “FS justices,” while other Republican-nominated justices will be referred to as “non–FS Republican–nominated justices.”[1]

Drawing from the literature on group polarization, this study contributes to our understanding of the influence of the Federalist Society by evaluating whether FS justices are insulated from the leftward ideological drift typical of justices on the Supreme Court (see Epstein et al. 2007). The results indicate that FS justices not only are insulated from leftward ideological drift but also typically exhibit rightward ideological drift over time. This has important implications for the ideological composition of the Court. Instead of becoming more moderate over time like their non–FS Republican–nominated peers, FS justices become more conservative. Thus, the ideological gap between FS justices on the Court and the Court’s liberal justices can be expected to grow over time, even if no Supreme Court seats are vacated due to retirement or death. In the context of a Court that includes six FS justices, these findings suggest that the Court’s outputs will become increasingly conservative over time and pose serious concerns about public perception of the Court’s legitimacy.

Prior Research on the Federalist Society

The body of published quantitative research on the Federalist Society is sparse, particularly concerning the network’s significant effect on the US legal system. That has, however, begun to change within the last two decades.

The first published quantitative research paper to focus directly on the ideologies of members of the Federalist Society at any level within the judicial system was by Scherer and Miller (2009). Evaluating judges on the Courts of Appeals in cases involving searches and seizures and states, they found that Federalist Society members are more conservative than are other Republican-nominated judges on the Courts of Appeals.

More recently, Bird and McGee (2023a) evaluated whether Federalist Society affiliation acts as a political signal in Senate judicial nominations and whether Federalist Society members have been especially likely to succeed in confirmation hearings in the “postnuclear” era—referring to the elimination of the filibuster for judicial nominations—leaving the minority party unable to block judicial nominations if 51 senators (or 50 senators and the vice president) are willing to vote to confirm the nomination. This study reveals that while the effect of Federalist Society affiliation on a nominee’s probability of successful confirmation was negligible prior to 2017, affiliation with the network has increased nominees’ probability of successful confirmation by roughly 20% in the postnuclear era. While the authors’ findings suggest that aspiring conservative judges have strong incentives to associate themselves with the Federalist Society in a postfilibuster era, their findings do not speak to the actual ideologies of justices on the Supreme Court. In a separate study, these researchers show that the Federalist Society has made substantial inroads in terms of influence on the US Courts of Appeals (Bird and McGee 2023b). They find that roughly 30% of judges on the US Courts of Appeals are active members of the Federalist Society and that on two such courts—the Fifth Circuit and the Eleventh Circuit—over 50% of judges are active Federalist Society judges.

Hollis-Brusky (2015) provides a comprehensive qualitative study focusing on the Federalist Society, exploring the ways in which the network’s members influence the Supreme Court’s decisions. Her work frames the Federalist Society as what she calls a “political epistemic network,” or PEN. A PEN, according to Hollis-Brusky, is “an interconnected network of experts who share certain beliefs and work to actively transmit and translate those beliefs into policy” (10–11). As a law-oriented PEN, members of the Federalist Society work to transmit their politically relevant legal knowledge to conservative law students through Federalist Society–sponsored debates and other events featuring conservative attorneys, law professors, judges, and politicians. Drawing on interviews, transcripts, and other documents, Hollis-Brusky argues that the Federalist Society has legitimized novel constitutional interpretations within a conservative framework. While she argues that the Federalist Society’s primary role as a political epistemic network is to provide legal arguments that support conservative policy positions (often through amicus curiae briefs submitted by its members to the Supreme Court), she also views the Federalist Society as a credentialing institution for conservative judges and attorneys.

Hollis-Brusky’s claim that most directly relates to the purpose of this study is that the Federalist Society also acts as a judicial audience. Prior research on judicial audiences finds that judicial audiences have pervasive effects on judges. For example, Baum (2006) evaluates the effects of several types of audiences on judges—including the public, court colleagues, the legal profession, and judges’ social peers—and finds evidence that judges are indeed influenced by judicial audiences. Meanwhile, Black and Owens (2016) find that the president is an influential judicial audience during periods of vacancy on the Supreme Court, as judges appearing on a president’s “short list” of potential nominees alter their decision making to curry favor with the president. Hollis-Brusky argues that the Federalist Society acts as a judicial audience for conservative judges that prevents these justices from drifting to the left ideologically over time, although she does not use quantitative analysis to assess this claim. Prior to the emergence of the Federalist Society as a dominant force in judicial politics, conventional wisdom held that most justices drift to the left ideologically over time and that this tendency was due at least in part to what is colloquially referred to as the “Greenhouse effect.” According to the Greenhouse effect, conservative justices became more ideologically moderate to curry favor with New York Times columnist Linda Greenhouse. Although prior research does confirm that the typical tendency is for judges to drift to the left ideologically over time (Epstein et al. 2007), no study prior to this one has quantitatively evaluated whether association with the Federalist Society insulates judges from the leftward ideological drift that many Supreme Court justices undergo.

This Open Judicial Politics study shows that while non–FS Republican–nominated justices typically exhibit leftward ideological drift over time, FS justices typically exhibit rightward ideological drift. These results reflect the process of group polarization. These results, taken together, suggest that we can expect a polarized Supreme Court both now and for the foreseeable future. The findings also have important implications for the Supreme Court’s decisions themselves, as Federalist Society–affiliated justices on the Supreme Court can now dictate the outcome of any given Supreme Court case.

History of the Federalist Society’s Jurisprudence

Members of this network generally advocate some version of originalist jurisprudence. When originalism first emerged in the 1970s and early 1980s, its advocates generally argued that the Constitution should be interpreted based on the “original intent” of its framers. By the mid-1980s, numerous legal scholars had pointed out serious flaws in this method of interpretation (e.g., Powell 1984). By the early 1990s, this “old originalism” focusing on the framers’ intent had been largely rejected, and a “new originalism” focusing on the “original public meaning” of the text had replaced it.

According to original public meaning, judges should interpret the Constitution based primarily on what the text actually says rather than through a search for its framers’ intent. Original public meaning is now the predominant form of originalism within the conservative legal movement (Barnett 1999). Those who promote the “original public meaning” approach claim that their method of interpreting the Constitution is the method (see Paulsen 2014; Lawson 2013), although even among conservative legal scholars, there remains a variety of formulations for what the original public meaning actually entails (Kay 2009).

While proponents of these various formulations of original public meaning typically argue that their methods constrain judges from following their own personal preferences, critics of public meaning originalism argue that it is “little more than a lawyer’s version of a magician’s parlor trick” (Cornell 2008) or “an ideal smokescreen behind which judges may pursue their personal moral, political, or economic goals with relative impunity” (Redish and Arnould 2011). Indeed, there is some evidence that originalists are largely unconstrained from voting according to their preferences, at least in cases involving the issue of federalism (Smith 2004).

The Theory of Group Polarization

Group polarization is the tendency of members of a relatively homogenous group to move toward a more extreme position than the position that the individuals initially held (Sunstein 1999). The process of group polarization appears to influence individuals in a variety of social contexts, including individuals’ attitudes and perceptions of others (Myers and Lamm 1976). The process of group polarization also appears to influence feelings toward the opposing political party (Iyengar and Westwood 2015).

Another important finding concerning group polarization is that individuals who are in attitudinally homogenous groups are more resistant to attitude change than individuals who are embedded in attitudinally heterogeneous groups, while attitudinally congruous networks strengthen the attitudes of the network’s members (Visser and Mirabile 2004). This is particularly noteworthy because Supreme Court justices often drift to the left ideologically over time (Epstein et al. 2007). If the process of group polarization influences those within the Federalist Society network, then FS justices should not only be relatively insulated from leftward ideological drift typically exhibited by justices on the Supreme Court but also move in a rightward direction over time. I expect that FS justices will drift to the right ideologically over time.[2]

Research Design

To evaluate this hypothesis, this study uses the Martin-Quinn dataset (Martin and Quinn 2002), which can be found at http://mqscores.wustl.edu/measures.php. This dataset includes ideology scores based on the voting of justices for each term of the Supreme Court from 1937 to 2021. Martin-Quinn ideology scores are generated through the statistical analysis of justices’ voting behavior each term. Therefore, each justice can have a different ideology score from one term to the next. In the dataset, Martin-Quinn ideology scores range from −4.491 (reflecting a very liberal ideology) to 4.153 (reflecting a very conservative ideology).

This study excludes all justices nominated by Democrats, as the focus is on whether and how FS justices differ from non–FS Republican–nominated justices. To limit the potential influence of partisan realignment on the results, the analysis includes judicial terms after the Federalist Society’s first annual symposium in April 1982. Thus, the dataset used in this study includes observations for each Republican-nominated justice for each term they were on the Court from the 1982 term through the 2021 term. Table 1 provides a list of all Republican-nominated justices who served on the Court during the period that the study covers.

| FS justices | Non–FS Republican–nominated justices | Democrat at the time of nomination |

|---|---|---|

| Antonin Scalia | Harry Blackmun | William J. Brennan Jr. |

| Clarence Thomas | Lewis F. Powell Jr. | – |

| John Roberts | William Rehnquist | – |

| Samuel Alito | John Paul Stevens | – |

| Neil Gorsuch | Sandra Day O’Connor | – |

| Brett Kavanaugh | Anthony Kennedy | – |

| Amy Coney Barrett | David Souter | – |

Among the 15 Republican-nominated justices who served on the Court between the 1982 and 2021 terms (which concluded in June 2022), seven have been affiliated with the Federalist Society. Moreover, among all 15 Republican-nominated justices in this dataset, Brennan is the only justice who was a Democrat at the time of their nomination to the Court. Because of this difference, I will run two sets of analyses below. The first will include all 15 Republican-nominated justices, and the second will remove Brennan, as he is something of an outlier.

To evaluate whether FS justices drift rightward ideologically over time, the dependent variable is average drift. Average drift is measured as the difference between the justice’s ideology score in the current term and the justice’s ideology score in their first term divided by the number of years the justice has been on the Supreme Court. Positive values of average drift indicate that the justice has moved to the right ideologically, while negative values indicate that the justice has moved to the left. For example, Justice Alito had a Martin-Quinn score of 1.422 in the October 2005 term but became more conservative over time. In the October 2021 term, his Martin-Quinn score was 2.473, giving him an average drift of 0.066 points during his time on the bench.

The key independent variable, Federalist Society, is a binary variable, which is coded 1 if the justice is or has ever been a member of the Federalist Society or a faculty adviser for a student chapter of the Federalist Society and 0 otherwise. Justices Thomas, Roberts, Alito, Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, and Barrett have all been members of the organization, while Justice Scalia was a faculty adviser for the student chapter at the University of Chicago Law School. These are the justices listed as FS justices in table 1.

Several control variables are also included. Federalist Society peers indicates how many FS justice peers serve alongside a given FS justice. This variable is included to account for the possibility that there may be a “critical mass” of FS justices necessary for group polarization to occur. Values range from 0 to 5. Original ideology is a measure of the justice’s Martin-Quinn score in his or her first term on the Court. This variable is included because a justice’s original ideology score will influence how much he or she can drift ideologically: a moderate justice has more room to drift to the right than a conservative justice. The variable chief justice is a binary variable coded as 1 or 0. This variable is a standard variable included in Supreme Court studies, as the chief justice (and Chief Justice Roberts in particular) is often viewed as being especially concerned with the perception that the Supreme Court is an apolitical institution that does not produce systematically partisan rulings. Indeed, prior research suggests that chief justices systematically change their behavior to protect the Court’s institutional cohesiveness and legitimacy (Lanier and Wood 2011).

For additional control variables, because justices might be expected to follow the pattern of political polarization exhibited by other political elites, I include the variable term, which indicates the Supreme Court term. A large body of research suggests that political elites have become more polarized over time, so controlling for the term mitigates the risk of mistakenly attributing rightward ideological drift among Republican-nominated justices to the Federalist Society rather than to long-term trends in polarization among political elites.

I do not include control variables for a justice’s gender or race because the results for a gender variable would be driven primarily by Justice O’Connor, and the results for a race variable would be driven exclusively by Justice Thomas. I do, however, include a dummy variable, Catholic, because the dataset includes four Protestant Republican–nominated justices and seven Catholic Republican–nominated justices and because of the possibility that religion influences the extent to which justices drift ideologically. Although I do not have a specific expectation concerning ideological drift among Catholic judges, a substantial body of prior research indicates that Catholic judges behave differently than judges of other religious backgrounds (see Pinello 2003; Idleman 2005). Catholic is coded as 0 if the justice is Protestant and 1 if the justice is Catholic. Justice Gorsuch is coded as a Protestant because he has claimed to attend an Anglican church, although he was raised Catholic.

The models presented below are ordinary least squares (OLS) regression models with observations clustered by justice, since observations for each justice will not be independent of one another.[3] Recall that because Justice Brennan was an outlier, I will estimate two models. Model 1 includes all Republican-nominated justices in the dataset, while model 2 excludes Brennan because he was a Democrat when he was nominated to the Supreme Court.

Results

The results in table 2 support the hypothesis that FS justices drift to the right of their non–FS Republican–nominated peers. In both models, association with the Federalist Society predicts an annual drift of roughly 0.12 points to the right of an otherwise identical non–FS Republican–nominated justice. Importantly, the coefficient for Federalist Society peers falls well short of significance in both models, indicating that there is not a “critical mass” in terms of the presence of Federalist Society members on the Court that induces FS justices to drift to the right ideologically over time. Instead, the effects of group polarization appear to be present for FS members regardless of how many FS peers are on the Court. In both models, higher original ideology scores on the Martin-Quinn scale are also associated with rightward ideological drift, as is the variable Catholic. In other words, Republican-nominated justices are likely to exhibit rightward ideological drift when they are Catholic, when they are more conservative to begin with, or when they are associated with the Federalist Society.

| Model 1 Republican-nominated justices |

Model 2 Republican-nominated justices, excluding Brennan |

|

|---|---|---|

| Federalist Society | 0.129***

(0.023) |

0.124***

(0.017) |

| Federalist Society peers | −0.002

(0.007) |

−0.001

(0.007) |

| Original ideology | 0.034**

(0.010) |

0.030*

(0.012) |

| Chief justice | −0.066*

(0.025) |

−0.061*

(0.028) |

| Term | −0.004*

(0.001) |

−0.004*

(0.002) |

| Catholic | 0.094**

(0.027) |

0.104**

(0.024) |

| Observations | 241 | 233 |

| R2 | 0.6813 | 0.6848 |

Standard errors in parentheses

*p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001

Note: Table 2 reports clustered OLS regression models predicting justices’ Martin-Quinn ideology scores for Republican-nominated justices. Model 1 includes all Republican-nominated justices. Model 2 excludes Justice Brennan because he was a Democrat at the time of his nomination.

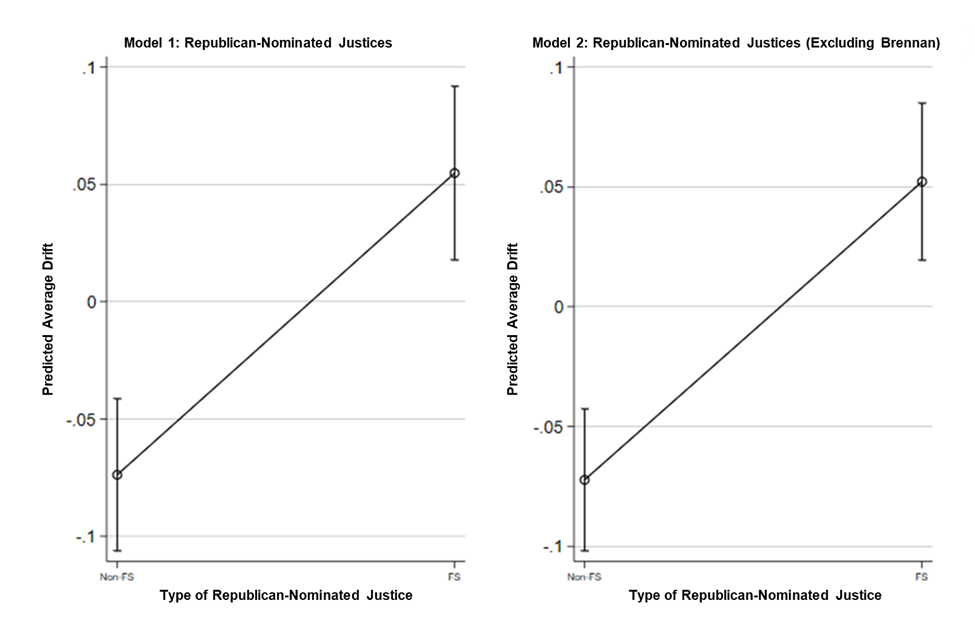

It should be noted that while an FS justice is expected to drift to the right of an otherwise identical Republican-nominated justice by roughly 0.12 points per year, the regression results in table 2 do not clarify whether FS justices are predicted to drift to the right ideologically. For example, if non–FS Republican–nominated justices are expected to drift to the left by −0.12 points, then the results would indicate that FS justices remain ideologically stable, while non–FS Republican–nominated justices drift to the left. To clarify whether FS justices drift to the right, figure 1 graphs average drift predictions for non–FS Republican–nominated justices and FS justices. The left panel of figure 1 graphs the results from model 1, while the right panel graphs the results from model 2.

The graphical results in figure 1 confirm that FS justices and non–FS Republican–nominated justices differ significantly in terms of their predicted ideological drift. In both models, FS justices are predicted to drift to the right by an average of 0.05 points on the Martin-Quinn scale per year. These results provide strong support for the hypothesis that justices associated with the Federalist Society will exhibit rightward ideological drift. Meanwhile, non–FS Republican–nominated justices drift to the left by −0.07 points on the Martin-Quinn ideology scale, on average. These results indicate that more than simply insulating FS justices from leftward drift, group polarization facilitates rightward ideological drift among FS justices.

These results suggest that if two justices were otherwise identical but one was associated with the Federalist Society, the Martin-Quinn ideology scores for these justices are expected to diverge by over 0.12 points per year. Over the course of 15 years, the ideologies of these two justices would diverge by over 1.8 points on the Martin-Quinn scale. Given that the most liberal justice (Justice Sotomayor) had a Martin-Quinn score of −4.137 in 2021 while the most conservative justice (Justice Thomas) had a score of 3.05, the predicted divergence between an FS justice and an otherwise identical non–FS Republican–nominated justice over the course of 15 years would represent about 25% of the entire range of ideology scores for justices in 2021 and more than the difference between the scores for the second most conservative justice (Justice Alito) and the median justice (Justice Kavanaugh).

The effect of Federalist Society membership is thus quite large in the long term. Federalist Society affiliation not only insulates justices from the leftward ideological drift that is typical of Supreme Court justices but also facilitates rightward ideological drift. Given that the Federalist Society has become the de facto gatekeeper for Supreme Court nominations during Republican presidencies, these results have important implications for the ideological composition of the Court and public perceptions of the Court’s legitimacy.

Discussion and Conclusion

Drawing from the literature on group polarization, this study provides new insights into how justices who are associated with the Federalist Society differ from other Republican-nominated justices by examining how FS justices and non–FS Republican–nominated justices drift ideologically over time. The results indicate that FS justices drift to the right ideologically, while their non–FS Republican–nominated peers drift to the left.

While justices associated with the Federalist Society are viewed as particularly conservative, only one prior study (Scherer and Miller 2009) evaluates the ideologies of judges who are associated with the Federalist Society at any level within the judicial hierarchy. And while Scherer and Miller (2009) find that judges on the Courts of Appeals are more conservative than other Republican-nominated judges, that study does not test any theories explaining why Federalist Society members might differ from other Republican-nominated judges.

These results have important implications, particularly in the context of an era in which Federalist Society membership is effectively a requirement for nomination to the Supreme Court under Republican administrations. First, because non–FS Republican–nominated justices who were nominated by Republicans typically drifted to the left ideologically over time and FS justices drift to the right, we can expect the Supreme Court to become more polarized over time, even without any new seats being vacated. Second, we should expect that highly divisive and salient Supreme Court decisions will typically be decided in a conservative direction for the foreseeable future, as a liberal decision would require two justices who are associated with the Federalist Society to join the three liberals on the Court.

And third, the combination of these factors—increased polarization within the Court and reliably conservative decisions on salient cases—will likely have significant effects on public perception of judicial legitimacy and support for the Court that, in the aggregate, undermine judicial legitimacy. This is because individuals’ perception of the Court’s legitimacy is tied to their ideological disagreement with the Court (see Bartels and Johnston 2020). If the public increasingly sees the Court as conservative and inclined to making ideologically motivated decisions, then conservatives will likely become more supportive of the Court. However, moderates and especially liberals will likely report more negative views of the Court and its legitimacy. Because the Supreme Court relies on the perception of its legitimacy to ensure that those tasked with implementing its decisions feel compelled to do so, the justices on the Supreme Court who are affiliated with the Federalist Society may weaken the Supreme Court in the long term.

While this chapter shows that the behavior of justices who are associated with the Federalist Society reflects group polarization, there is much more left to learn about the influence of the Federalist Society on law and politics in the United States. One potential avenue for future research is to evaluate the content of opinions themselves. There are numerous hypotheses concerning the Federalist Society and the effects of its members’ views that could be evaluated through the application of text analysis methods to Supreme Court decisions. For instance, because one of the major goals of the Federalist Society is to spread strong conservative legal arguments among members of the conservative legal movement, researchers might consider evaluating whether opinions written by justices who are associated with the Federalist Society are especially likely to borrow language from amicus curiae briefs written by individuals who are associated with the Federalist Society. Analysis of this kind could help quantify the extent to which the Federalist Society has influenced the law. Another area worth considering is the tone of opinions. Prior research has found that justices who feel especially strongly about a given issue will use more disagreeable rhetoric (Wedeking and Zilis 2018; Zilis and Wedeking 2020). Because the process of group polarization leads members of a group to both hold more extreme views and hold them more strongly, we might expect opinions written by Federalist Society members to use more disagreeable language than opinions written by other justices—particularly in cases that concern issues about which Federalist Society members hold especially strong views.

Finally, future research should focus on how Federalist Society–affiliated justices’ control of the Supreme Court influences public attitudes toward the Court. Survey experiments might provide important insights into how the Federalist Society influences public perception of the Court’s legitimacy, particularly for groups that have been affected by recent rulings such as Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization (2022) and Students for Fair Admissions v. President and Fellows of Harvard College (2023).

While the Federalist Society clearly has a powerful influence on judicial politics in the United States, academic literature on the network is remarkably sparse. However, that is beginning to change. Indeed, new academic scholarship on the network has been published within the last year (see Bird and McGee 2023a, 2023b). The subfield of judicial politics concerned with the Federalist Society and its influence is poised to grow dramatically over the next several years as researchers increasingly recognize the influential role the network plays throughout the judicial hierarchy.

Learning Activity

- Break students up into small groups and ask them to discuss the implications of this study. Specifically, what does the tendency for FS justices to drift to the right suggest about the long-term effects of the Federalist Society’s dominant role on the Supreme Court?

- Assign each group to one of the Federalist Society–affiliated justices confirmed to the Supreme Court under the Trump administration. Each group should evaluate the demographic characteristics of the justice that has been assigned to them, considering attributes such as age, race, gender, religion, and educational background.

- Have students present what they learned about the justice to the whole class.

- Once all groups have presented what they have learned, have students discuss, as a full class, what these characteristics tell us about the priorities of Leonard Leo, who helped Trump create his list of potential nominees.

References

Barnett, R. E. 1999. “An originalism for nonoriginalists.” Loy. L. Rev., 45, 611.

Bartels, B. L., and Johnston, C. D. 2020. Curbing the court: Why the public constrains judicial independence. Cambridge University Press.

Baum, L. 2006. Judges and their audiences: A perspective on judicial behavior. Princeton University Press.

Bird, C. C., and McGee, Z. A. 2023a. “Going nuclear: Federalist society affiliated judicial nominees’ prospects and a new era of confirmation politics.” American Politics Research, 51(1), 37–56.

Bird, C. C., and McGee, Z. A. 2023b. “Looking forward: Interest group legal strategy and federalist society affiliation in the United States circuit courts of appeal.” Polity, 55(2), 389–99.

Black, R. C., and Owens, R. J. 2016. “Courting the president: How circuit court judges alter their behavior for promotion to the Supreme Court.” American Journal of Political Science, 60(1), 30–43.

Cornell, S. 2008. “Originalism on trial: The use and abuse of history in District of Columbia v. Heller.” Ohio State Law Journal, 69(4), 625–40.

Epstein, L., Martin, A. D., Quinn, K. M., and Segal, J. A. 2007. “Ideological drift among supreme court justices: Who, when, and how important.” Nw. UL Rev., 101(4), 1483–1542.

Hollis-Brusky, A. 2015. Ideas with consequences: The Federalist Society and the conservative counterrevolution. Oxford University Press.

Idleman, S. C. 2005. “The concealment of religious values in judicial decisionmaking.” Virginia Law Review, 91(2), 515–34.

Iyengar, S., and Westwood, S. J. 2015. “Fear and loathing across party lines: New evidence on group polarization.” American Journal of Political Science, 59(3), 690–707.

Kay, R. S. 2009. “Original intention and public meaning in constitutional interpretation.” Nw. UL Rev., 103, 703.

Lanier, D., and Wood, S. L. 2011. “Moving on up: Institutional position, politics and the chief justice.” Politics and the Chief Justice, May 19.

Lawson, Gary. 2013. “Originalism without obligation.” BUL Rev., 93(4), 1309–18.

Martin, Andrew D., and Quinn, Kevin M. 2002. “Dynamic ideal point estimation via Markov chain Monte Carlo for the U.S. Supreme Court, 1953–1999.” Political Analysis, 10, 134–53.

Myers, D. G., and Lamm, H. 1976. “The group polarization phenomenon.” Psychological Bulletin, 83(4), 602–27.

Paulsen, M. 2014. “The text, the whole text, and nothing but the text, so help me god: Un-writing Amar’s unwritten constitution.” University of Chicago Law Review, 81(3), 1385–1442.

Pinello, D. R. 2003. Gay rights and American law. Cambridge University Press.

Powell, H. J. 1984. “The original understanding of original intent.” Harv. L. Rev., 98, 885.

Redish, M. H., and Arnould, M. B. 2012. “Judicial review, constitutional interpretation, and the democratic dilemma: Proposing controlled activism alternative.” Florida Law Review, 64(6), 1485–1538.

Scherer, Nancy, and Miller, Banks. 2009. “The Federalist Society’s influence on the federal judiciary.” Political Research Quarterly, 62(2), 366–78.

Smith, P. J. 2004. “Sources of federalism: An empirical analysis of the court’s quest for original meaning.” UCLA L. Rev., 52, 217.

Sunstein, C. R. 1999. “The law of group polarization.” University of Chicago Law School, John M. Olin Law and Economics Working Paper (91).

Teles, Steven M. 2008. The rise of the conservative legal movement. Princeton University Press.

Visser, Penny S., and Mirabile, Robert R. 2004. “Attitudes in the social context: The Impact of social network composition on individual-level attitude strength.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(6), 779–95.

Wedeking, J., and Zilis, M. A. 2018. “Disagreeable rhetoric and the prospect of public opposition: Opinion moderation on the US Supreme Court.” Political Research Quarterly, 71(2), 380–94.

Zilis, M., and Wedeking, J. 2020. “The sources and consequences of political rhetoric: Issue importance, collegial bargaining, and disagreeable rhetoric in Supreme Court opinions.” Journal of Law and Courts, 8(2), 203–27.

- Even though they existed prior to the Federalist Society, the term traditional would mistakenly imply that these judges were unified in their views on jurisprudence or public policy when, in fact, they were not. Non–FS Republican–nominated justices were more ideologically heterogeneous than FS justices, and some even eventually developed liberal reputations. ↵

- One possible concern is whether FS justices engage in ideological drift only after reaching a critical mass in terms of their presence on the Supreme Court. To address this concern, I include the variable Federalist Society peers, which indicates the number of FS peers an FS justice has on the Court in a given term. ↵

- To address possible concerns regarding multicollinearity among independent variables, I calculated variance inflation factor (VIF) values for each variable in all four models. Across both models, the highest VIF value for a variable is 8.51, indicating that multicollinearity, while present, is not a major concern given the independent variables included in these models. ↵