Actors in the Judicial Process

17 A Matter of Great Importance

Interest Groups, the Senate Judiciary Committee, and Supreme Court Confirmation Hearings

Abigail V. Hassett; Elizabeth A. Lane; and Jessica A. Schoenherr

Research is funded by the Arlen Specter Center Research Fellowship and the Michigan State University Department of Political Science. We thank Ashley Taylor for her help navigating the Specter Archives; Karen Albert and Evan Laine for providing feedback; Jasmine Jordan and Hana Lerwick for research assistance; and Miles Armaly, Ryan Black, Ian Ostrander, and Emma Slonina for their comments.

Introduction

After Justice Lewis Powell announced his retirement from the Supreme Court on June 26, 1987, President Ronald Reagan took less than a week to nominate Judge Robert Bork to replace him (Abraham 2007). Reagan’s counselors were confident their selection would join the Court and transform it into the conservative institution Republicans had long sought (Kirk et al. 2020). Bork was a verified conservative, but he had a record that made it difficult to argue he was unfit for the job; the unanimous confirmation of imminently qualified Judge Antonin Scalia the previous year showed the administration that qualifications could trump ideological concerns (Calmes 2021). But the administration misjudged the political climate before them, which had changed dramatically since Scalia’s nomination. Less than 45 minutes after Reagan’s announcement, Democratic senator Ted Kennedy lambasted the nominee on the Senate floor, describing “Robert Bork’s America” as “a land in which women would be forced into back-alley abortions, blacks would sit at segregated lunch counters, rogue police could break down citizens’ doors in midnight raids, schoolchildren could not be taught about evolution, writers and artists could be censored at the whim of government, and the doors of the federal courts would be shut on the fingers of millions of citizens for whom the judiciary is—and is often the only—protector of the individual rights that are at the heart of our democracy” (Kennedy 2009, 406).

Having pulled the fire alarm, Kennedy and other Democratic senators moved to extinguish Bork’s nomination (Kennedy 2009). Kennedy recruited different groups to speak out against Bork, and more than 80 of them expressed opposition to his nomination, including the NAACP and NOW (Cameron et al. 2020). Senators in both parties found themselves dissecting Bork’s record during his mid-September confirmation hearings, and Bork did little to assuage the concerns senators raised (Kagan 1995). By late October, the Senate voted 58–42 to deny Bork the seat (Toobin 2008), and Reagan’s slam-dunk nominee became the textbook example of how not to get confirmed to the Court.

Robert Bork’s nomination to the Supreme Court was a watershed moment in Supreme Court history, at least in part because it caused a seismic shift in interest groups’ participation in the process (Cameron et al. 2020). Interest groups have always used their resources to provide information to resource-strapped legislators (Hall and Deardorff 2006; Scherer, Bartels, and Steigerwalt 2008), but they also, when appropriate, provide that same information to the public for use in grassroots campaigns (Kollman 1998). Since at least the late 1960s, these political stakeholders have also provided information about Supreme Court nominees to political officials and the public, acknowledging that nominees can influence policy outcomes for decades if they get confirmed (Steigerwalt 2010). But starting with Judge Bork, interest groups began weaponizing their information-collection-and-dissemination processes, drawing public attention toward nominees, putting pressure on senators to vote a certain way, and consequently helping shape the federal bench (Cameron and Kastellec 2023). Interest groups are now powerful players in the judicial nomination process (Cameron, Kastellec, and Park 2013), and they show no interest in ceding their influence; the interest group–driven chaos that surrounded the Bork nomination and confirmation is now the new normal.

We seek to better understand the information interest groups provide senators when they organize and lobby for or against a Supreme Court nominee. We focus on one tactic—information provision via briefing books and letters—to answer some questions: What are political stakeholders saying to senators? More specifically, what information are interest groups providing that makes them so influential? And how does that information differ from the “official” information provided by the White House? We look to the Senate Judiciary Committee, which is tasked with collecting information on a nominee and providing that information to the rest of the Senate (Collins and Ringhand 2013), for answers. Using content analyses of briefing books and constituent letters sent to Republican senator Arlen Specter, a notoriously unreliable partisan, during the Bork hearings, we show that interest groups help senators condense a nominee’s body of work into small categories with headlined topics, and they highlight information that even the officials tasked with vetting the nominee might not expect to be important. Interest groups, in short, highlight problems, and they do so in a manner that is easy for senators—and any constituents who see the interest group’s work—to consume.

In conducting this analysis, we provide two key contributions to the study of Supreme Court nominations and confirmations. First, we analyze the information that interest groups provide senators. While interest groups’ key tactic in these hearings is information provision (Caldeira and Wright 1998; Steigerwalt 2010), scholars often focus strictly on groups’ presence in the process (see, e.g., Cameron et al. 2020; Farganis and Wedeking 2014; Schoenherr, Lane, and Armaly 2020). Few have studied the content of the information these groups provide to see what makes it useful. We use the White House and interest group briefing books as well as constituent letters to a senator to examine their messages. Because we have data from three different sources, we are also able to compare how interest groups’ concerns match the concerns outlined in constituent letters as well as the government’s own talking points on the nominee. Consequently, we provide an initial examination of the informational value of these important documents.

Second, we follow in the steps of scholars like Howard and Roberts (2015) and use senators’ personal papers to study the broader legislative process. Senators’ papers provide a unique perspective on who approached senators, how they did so, and how the senator reacted to the appeal. Research on members of Congress tends to focus on their public statements (see, e.g., Grimmer 2013; Ramey, Klinger, and Hollibaugh 2017), but understanding personal appeals and private reactions is just as important for understanding how legislators approach their jobs. With the Supreme Court confirmation process, an insider look is especially important because, while it is clear that private appeals matter, scholars have struggled to understand how. To be sure, scholars have gotten creative with their approaches, using raw counts of interest group activities (Epstein and Segal 2005; Farganis and Wedeking 2014), interviews (Caldeira and Wright 1998; Caldeira, Hojnacki, and Wright 2000; Steigerwalt 2010), and newspapers (Cameron et al. 2020; Cameron, Kastellec, and Park 2013) to examine interest groups’ involvement in the process. But by going directly to the information source, we offer a new approach to examining interest groups and their attempts to influence legislators.

Supreme Court Confirmations and Interest Groups

Article II, Section 2 of the Constitution tasks the Senate with offering “advice and consent” on the president’s nominees to the Supreme Court, which today means investigating a nominee and holding a formal confirmation vote (Epstein and Segal 2005). After the president selects his nominee and introduces her to the public, he sends the nomination to the Senate for immediate referral to the Judiciary Committee (Collins and Ringhand 2013). After receiving the nomination, the Judiciary Committee opens an investigation into the nominee that includes an FBI background check, a written questionnaire, and meetings with relevant interest groups, sponsors, advocates, and the nominee herself (Nemacheck 2008; Steigerwalt 2010). After the initial investigation, the Judiciary Committee asks the nominee to appear at a public confirmation hearing (Farganis and Wedeking 2014). The Judiciary Committee then votes on whether they recommend confirmation; regardless of the outcome, the committee always sends the nominee to the floor for a full Senate vote (Collins and Ringhand 2016). With one notable exception (Judge Merrick Garland’s 2016 nomination to replace Justice Antonin Scalia), the Senate Judiciary Committee always schedules confirmation hearings for the president’s nominee (Kaplan 2018), and every nominee who makes it to a confirmation hearing receives an up or down vote on the Senate floor. Since 2017, Supreme Court nominees only need a majority of votes to get confirmed.

While senators offer varying degrees of attentiveness to most executive branch appointments, including potential lower court judges, Supreme Court nominees always receive their full attention (Steigerwalt 2010). This attention is politically motivated, as senators are reelection minded (Grimmer 2013; Mayhew 1974), Supreme Court openings are widely broadcast (Johnson and Roberts 2004), confirmation hearings are salient (Farganis and Wedeking 2014), and constituents consequently hold senators accountable for their votes on Supreme Court nominees (Kastellec, Lax, and Phillips 2010). Increased partisan polarization among the public and within the Senate also magnifies the importance of a Supreme Court vote, with each fight helping partisans on both sides gain political ground (Cameron, Kastellec, and Park 2013; Lee 2009; Smith 2007). Because presidents are politically savvy actors who pick nominees with an eye toward confirmation, the public typically supports the nominee and the Senate almost always confirms her (Krutz, Fleisher, and Bond 1998; Moraski and Shipan 1999; Nemacheck 2008), but few nominees are confirmed without answering a few well-placed political questions from senators who might need ammunition for later political gain (Schoenherr, Lane, and Armaly 2020).

For senators, the key to a successful nomination process is knowing how to approach the nominee—what to ask and how to ask it to score political points—which means they need information about the nominee and her record. Members of the Senate Judiciary Committee are responsible for uncovering and disseminating this information, and they take this information provision role seriously (Collins and Ringhand 2013), with each party deploying its own investigatory committee and individual senators engaging in their own information-gathering activities (Nemacheck 2008; Steigerwalt 2010). Senators also receive information from the White House, which provides nominee summaries based on details provided during its own vetting process (Davis 2017). Information on Supreme Court nominees is widely available, but it is up to the Judiciary Committee members and their staffs to sort through the mountain of information, summarize it for their colleagues, and then figure out which questions they need to ask at the confirmation hearing. Senators do this task while fulfilling their other responsibilities, including investigating about 46 lower court judges every year (US Courts 2023) and reviewing legislation that falls under the committee’s jurisdiction (Epstein and Segal 2005). Given that time is finite, senators look for help finding the important information, and interest groups provide that help.

When it comes to Supreme Court nominees, interest groups can trade a service—analyzing a nominee’s background and providing committee members with the highlights—for influence (Scherer, Bartels, and Steigerwalt 2008). This information can include but is not limited to written analyses of a nominee’s voting record, highlights of relevant speeches and decisions (Caldeira, Hojnacki, and Wright 2000; Steigerwalt 2010), projections on how a nominee will vote once he or she is confirmed, and data on how constituents feel about the nominee (Caldeira and Wright 1998). Because interest groups are invested in outcomes, the information they provide is undoubtedly biased toward their goals, but that does not make it useless. Groups that support the nominee will provide details that make the nominee look good, while groups that oppose the nomination will point out problems in the nominee’s record. Interest groups can also decide how to disseminate the information they have. They can publicly engage in grassroots lobbying (Caldeira, Hojnacki, and Wright 2000; Cohen 1998), or they can provide the information directly to the senators (Hall and Deardorff 2006). Regardless of how an interest group chooses to make their appeal, a senator who chooses to ignore their material does so at his potential electoral peril; the same groups that mobilize to support or oppose Supreme Court nominations can also mobilize in support of or opposition to senators based on their voting behavior (Epstein and Segal 2005; Scherer 2005).

Interest groups have had significant success exchanging information for influence in the Supreme Court nomination and confirmation process. The minute an opening appears, groups mobilize in preparation for supporting or rejecting the president’s nominee (Cameron et al. 2020). Understanding the value interest groups have and the power they hold over the process, presidents consult different interest groups about nominees and seek their approval before they announce their selections (Kirk et al. 2020; Nemacheck 2008). The information that interest groups provide regarding a nominee’s record and constituents’ feelings about her can influence how a senator votes on that nominee (Gibson and Caldeira 2009), and nominees who find themselves fighting a lopsidedly large number of opposition groups are less likely to secure confirmation (Cameron, Kastellec, and Park 2013). Interest groups influence the confirmation process, and information provision is one of their paths to obtaining that influence.

Examining Interest Groups’ Information

Information provision is a tactical process. Steigerwalt (2010) interviewed a former senator and several Senate staffers about judicial nominations and found that interest groups are strategic in whom they target with research. Liberal-learning interest groups only contact ideologically sympathetic senators or moderate senators who might “flip” and vote with the Democrats. They did not waste their resources appealing to conservative senators, as they were unlikely to use the information provided. Conservative groups, on the other hand, typically provided senators with very little information about a nominee, something that conservative senators found endlessly frustrating, as they too wanted interest group help in sorting through information (Steigerwalt 2010).[1]

To examine the information provided by interest groups, then, we find ourselves focusing on the documents that organized interests provided to one senator in particular: Senator Arlen Specter of Pennsylvania. We opted to use Specter’s papers for several reasons. First, he was a notoriously independent Republican (and, later, Democrat) on the Senate Judiciary Committee who voted on the winning side of every one of the 13 nominations he saw between 1981 and 2010 (Lockman and Schertzer 2017). Both parties were convinced that his vote was crucial for validating or invalidating a nominee’s credentials (Specter and Robbins 2002), which made him an obvious target for “flipping” and thus an interest group target. Second, Specter sat on the Judiciary Committee for the entirety of the televised confirmation era, something that is particularly important given that C-SPAN’s decision to air the hearings in 1981 inherently changed senators’ approach to the process (Farganis and Wedeking 2014). Finally, Specter’s personal papers are available to researchers through the Arlen Specter Center for Public Service (Specter 2018), unlike the personal papers of many of his Judiciary Committee peers.[2]

In order to systematically examine the types of information interest groups provided Senator Specter, we went to the archives at the University of Pittsburgh and photographed nearly every document contained in the archives relating to Supreme Court nominations.[3],[4] We focused our activities on typed material and did not include anything handwritten, such as Specter’s notes on documents, handwritten speech drafts, handwritten letters, or notes passed between Specter and his staff or other senators. In all, we took almost 7,000 photographs of 877 different documents. Upon full review of the documents we collected, we unfortunately discovered that many of the nominees’ files were incomplete. One file that was not, however, was Robert Bork’s. Fifty-seven percent of the pictures that we took came from Specter’s files on Robert Bork (just shy of 3,800 pages), and the senator’s staff kept as much information as possible for the hearing that made Specter famous. Given Bork was the turning point in confirmation hearings for a multitude of reasons (Cameron et al. 2020; Epstein et al. 2006), we decided that studying his hearings in detail was a worthwhile venture. Consequently, we focus our analysis in this chapter on the information that interest groups, the White House, and constituents provided Senator Specter throughout Judge Bork’s nomination process.

Methodology

Most of the documents we photographed spanned multiple pages and, therefore, multiple photographs, so we grouped the photographs of the same documents together and then divided those collections into one of seven categories: (1) briefing books, (2) cases, (3) letters, (4) news media (e.g., newspaper clippings, magazines, etc.), (5) nominee background (e.g., law review articles written by the nominee, copies of the nominee’s speeches, and other written work), (6) Specter’s notes, and (7) office communication. With the documents gathered and organized, we then sought to turn these photographs into computer-readable text files. Photographs alone would only enable us to read the documents outside of the library, but we wanted to do more systematic research of the text itself, so we turned the pictures into text-readable files. To do this, we relied on a popular optical character recognition (OCR) software, ABBYY FineReader. The OCR software read typed text from the photographs we took and translated it into a raw text file, which we could then use to perform a wide variety of content analyses.

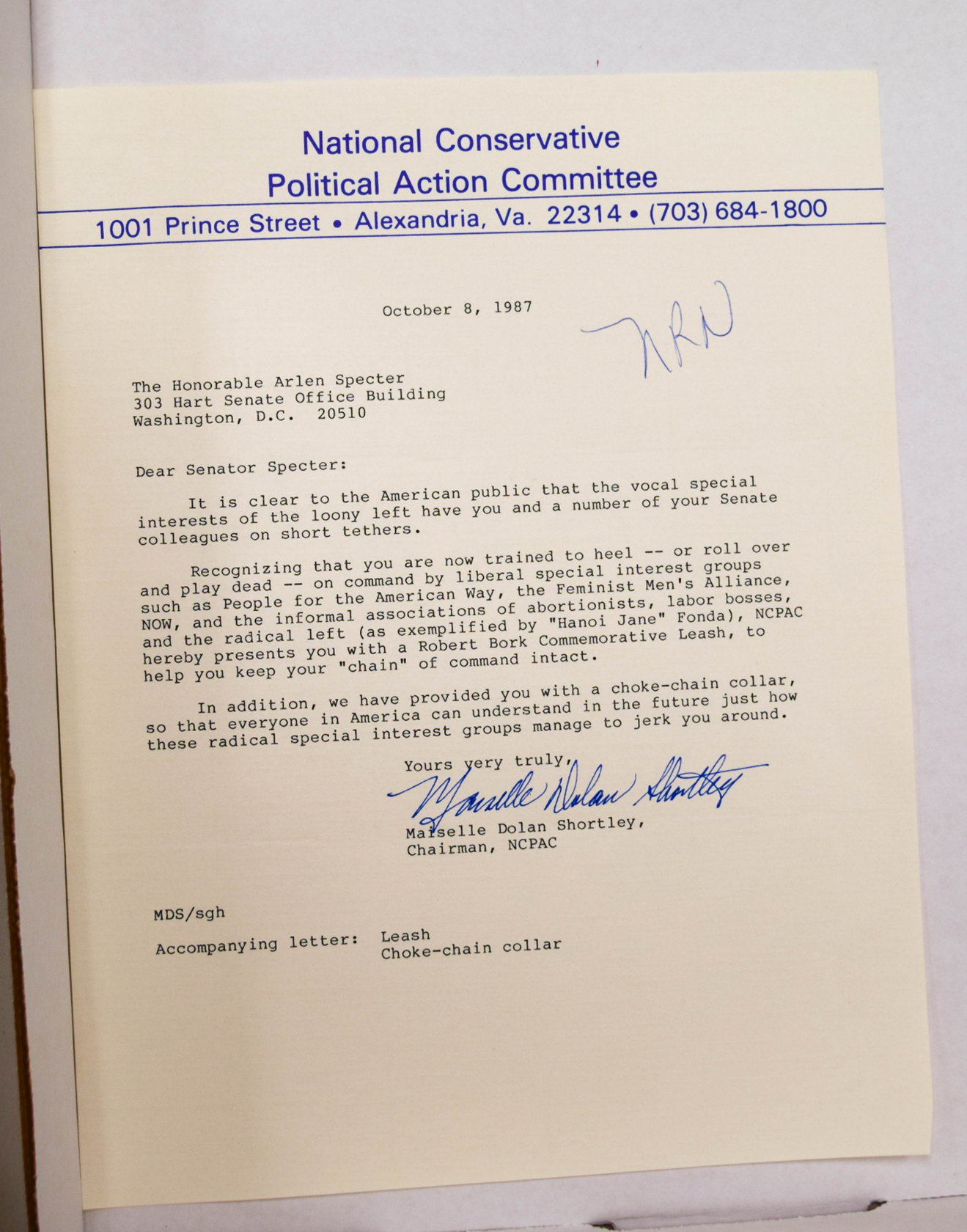

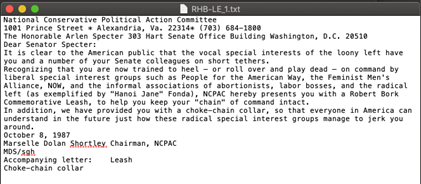

To see exactly how ABBYY works, see figure 1. This is a photograph of a colorful letter sent to Specter by the National Conservative Political Action Committee just two days after Bork’s failed confirmation. Figure 2 is a screenshot of the raw text file produced by ABBYY FineReader after running the photograph in figure 1 through the optical recognition software. With this text file, we can search for words, count their frequency, and utilize more complicated text analysis techniques to better understand the information contained within the documents that Specter received.

After gathering the information and converting it to text, we decided to take an unsupervised topic modeling approach to systematically and empirically analyze the content of three types of documents contained in the Bork files: (1) briefing books compiled by the Reagan administration and sent to each senator, (2) briefing books compiled by interest groups and sent to Senator Specter, and (3) letters about the Bork nomination that Specter received and kept in his files.

Our decision to focus on these three pieces of information is purposeful, as we want to study the information provided to Specter on a broad level while simultaneously comparing the interest groups’ information to that provided by other sources, particularly the “official” information provided by the White House and the more grassroots engagement by constituents via letters. We have two government briefing books: one produced at the beginning of the nomination process that covered Bork’s background and a second, more comprehensive guide issued after criticism of Bork increased. We also went through documents from 23 different interest groups, nearly all of them liberal-leaning ones like the American Civil Liberties Union and the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. Finally, we examined the texts of 72 constituent letters sent to Specter. These letters came from friends, former representatives, professors at the major law schools in Pennsylvania, and national groups, all involving short notes and personalized pleas to Specter regarding the nominee.

Our goal is to identify the topics covered in organized interest groups’ briefing books so that we can compare them to the information provided by constituent letters and the White House itself, so we needed a way to systematically work through the information contained in the documents. Historically, people collected data like this by hand, reading through each book and keeping track of each topic that was discussed between its covers (Grimmer and Stewart 2013). Such data collection would result in a list of all the concepts discussed in each book and across all the books, along with a measure of the frequency with which each topic was mentioned. This type of coding requires preestablished categories created based on assumptions about the documents in front of them (Rice 2019). We were hesitant to make assumptions about what was in the briefing books—after all, as figure 1 shows, Specter certainly received some unexpected items. Worse, 30 years of post-Bork analysis have also left preconceived notions about the topics covered during the process, which could bias the coders before they even begin coding. Humans are not ideal for coding this kind of data (Schoenherr and Black 2019), so we decided to let machine learning processes do the work instead.

We utilize a computer-assisted methodology called unsupervised topic modeling, which uses word frequencies to identify latent concepts or the topics contained in texts (Rice 2019). Rather than telling the computer which topics to look for, topic modeling tells a researcher which words tend to be grouped together, letting them see the topics that were covered. The researcher then labels these groups of words as belonging to certain topics. Ultimately, the researcher decides how broad or narrow to make the topics by specifying how many concepts the model should identify, but the model does the rest of the work. Given the thousands of pages of text to examine, the fallibility of human coders, and our desire to avoid bringing preconceived notions of topics into the analysis, supervised topic modeling was the best option for this project.

We preprocessed the text before analyzing it, removing punctuation, numbers, unnecessary white space, and stopwords like the or and. Additionally, we broke all words down into their stems so that words like judge, judges, and judging all get treated as the same word during our analysis. Removing punctuation and stopwords and destemming the remaining words reduces the number of parameters under examination (Manning and Schutze 1999). This consequently makes it easier to draw inferences about the words used in a document. We cleaned our data and conducted our analyses using quanteda, an R package for text management and analysis developed by Kenneth Benoit and his colleagues (Benoit et al. 2017).

Analysis

Because our project is exploratory, our focus is more on content than on why the information is there in the first place. We thus begin our analysis by looking at the information contained in the White House briefing books so that we have a baseline of information—namely, the information provided by the “official” keepers of Bork’s nomination who first introduced him to the public and were most invested in his confirmation. From there, we examine how interest groups diverged from the official line or maintained the status quo of information. Finally, we conclude with a look at constituent letters sent to Senator Specter throughout his confirmation hearing, with an eye toward identifying the information conveyed in these shorter documents.

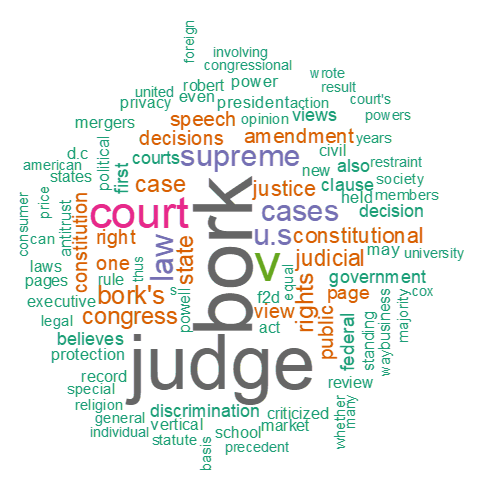

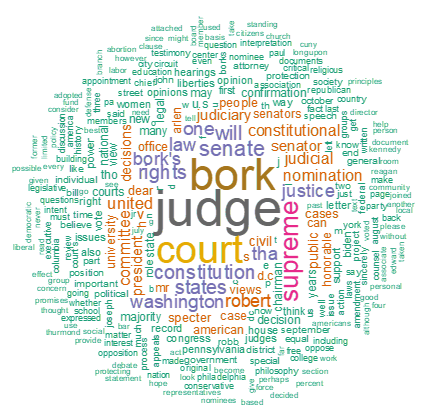

We start our analysis of each of the three document types by looking at the word clouds of the documents. Word clouds visually show the frequency with which certain words occur across a set of texts, helping researchers identify keywords in documents. Figure 3 displays the word cloud of the top 100 words that appear in the White House briefing books. The words that are larger and toward the center of the cloud are the words that appear most frequently in the documents; as you move away from the center and toward the perimeter of the circle, the words that appear less frequently (though still frequently enough to be one of the top 100 words) are in green. Unsurprisingly, the most frequently used words in the White House briefing books are bork and judge. Moving away from the center of figure 3, however, shows the government briefing books focused on Bork’s record, with words like religion, antitrust,[5] privacy, and discrimination appearing frequently in the documents. This word cloud lacks sentimental words like feel or support, focusing instead on issue areas, which suggests the White House focused on Bork’s qualifications for the job and not peoples’ affective responses to his rulings.

The results of the topic model better illuminate the content of the White House briefing books. We instructed the model to break the text down into 15 topics based on trial and error—the models with 10 categories collapsed too much information into a single category, while the model with 20 categories provided repeated categories, including two nearly identical Establishment Clause categories. Table 1 shows some of the words that appear in each topic along with our interpretation of the topics those words represent. Of our 15 categories, we threw out one because it contained mainly initials (H, which stood for Bork’s middle name, Heron, or v, as in the letter that separates the petitioner from the respondent in a case name). The remaining categories confirm our suspicions from table 3 that the White House focused on Judge Bork’s past rulings and job qualifications.

| Topic | Keywords |

|---|---|

| Replacing Powell | powell, liberty, nomination, individual |

| Presidential power and Watergate | cox, fire, prosecutor, president |

| Antitrust | merger, horizontal, antitrust, competition |

| Price fixing | price, fix, vertical, antitrust |

| Nuclear power | nrc, nuclear, market, regulation |

| Decision making | enforce, decision, veto, amendment |

| Federalism and equal protection | federalist, equal, school, clause |

| Business | consumer, business, interest, challenge |

| Establishment Clause | first, amend, speech, religion |

| Privacy | precedent, discrimination, privacy, protect |

| Free speech and press | press, freedom, libel, speech |

| Employment discrimination | employ, health, standing, policy |

| Congress | right, action, branch, congress |

| Judicial philosophy | restraint, decision, philosophy, citizen |

As table 1 shows, the White House focused at least part of its attention on the man Bork was replacing, Lewis F. Powell. Presidents pay attention to nominees who might change the balance of the Court (Krehbiel 2007; Moraski and Shipan 1999), and Reagan wanted the conservative Bork to replace the moderate Powell and, consequently, make the Court more conservative (Toobin 2008). The White House thus understandably put energy into explaining Bork’s suitability as a replacement. Beyond that logistical issue, however, the White House almost exclusively wrote about Bork’s academic and judicial work on different issue areas. They talked about his specialty area, antitrust law, as well as his views on privacy and free speech, two areas in which Democrats raised concerns about Bork’s views. Importantly, the White House also spent time walking through his association with Watergate, as then solicitor general Bork was the one who fired Special Prosecutor Archibald Cox after the attorney general and his deputy resigned rather than do it themselves (Nobel 1987). In all, the government supplied senators with information about Bork’s engagement with 13 different areas of law, all presented as factual and all undoubtedly analyzed with an eye toward helping Bork win confirmation.

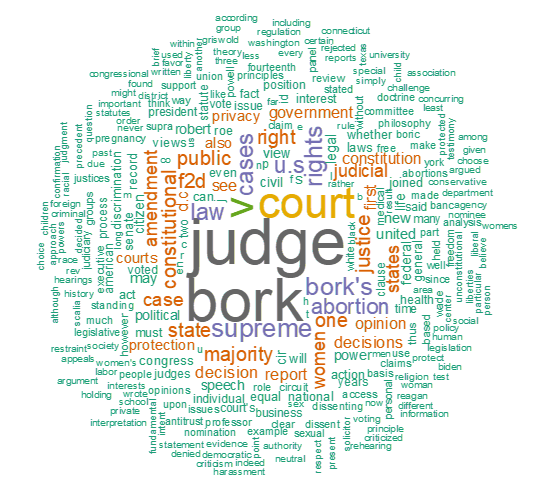

Interestingly, one issue area the Reagan White House did not discuss was abortion. Kennedy’s opening salvo established that Bork’s rulings on abortion threatened the viability of Roe v. Wade (1973), but the White House brushed past it. Its vague focus on privacy did not lead to a specific discussion of reproductive rights. Interest groups did talk about abortion, however. As figure 4 shows, abortion was among the top 300 words used by interest groups in their briefing books, appearing 634 times. The government may have focused on Bork’s qualifications, but the interest groups emphasized their problems with his rulings. Other words that appeared frequently included women, rights, and justice. Based on the word cloud from these 23 briefing books, the interest groups provided very different information from their White House counterparts.

When looking at the topics covered in the interest group briefing books, the differences between the White House’s discussion of Bork and interest groups’ own analyses appear clearly. We again broke the briefing books down into 15 topics, and we again threw out one category for being a hodgepodge of random letters. As table 2 shows, interest groups also focused on multiple areas of the law, though they wanted to draw senators’ attention to civil rights, voting rights, and abortion, three areas the government avoided in its briefing books. Organized interest groups’ discussion of privacy focused on reproductive rights, and they explicitly discussed abortion and the Court’s ruling in Roe. The interest groups hit exactly the topics that Kennedy outlined in his speech, even if the government did not. Like their government counterparts, they did not use affective language to do it either; they, too, focused on just the facts.

| Topic | Keywords |

|---|---|

| Explanation for ending | citizen, public, interest, group |

| Appointment and nomination | senate, nomination, confirm, Reagan |

| Legal jargon | case, state, special, supra |

| Judicial decision making | decision, decided, reverse, precedent |

| Reports and overviews | report, view, criticism, posit |

| Previous rulings | en banc, district, dissent, circuit |

| Comparison to other judges | Powell, white, Black, Harlan |

| Separation of powers | constitution, power, executive, legislative |

| Civil rights and voting rights | fourteenth, racial, poll, Black |

| Free expression | first, speech, expression, freedom |

| Right to privacy | privacy, Griswold, protect, marriage |

| Equal protection and discrimination | discrimination, women, sex, race |

| Abortion | abort, women, wade, physician |

| Antitrust | antitrust, solicitor, statute, protect |

Interestingly, interest groups engaged in comparisons, which is something the White House did not do. Obviously, interest groups mentioned the now departed Justice Powell, but they also brought up the other justices. They mentioned Justice Byron White, who wrote the dissenting opinion in Roe; Justice Hugo Black, who was a fervent civil rights advocate; and Justice John Marshall Harlan II, the poster child for adhering to precedent (Woodward and Armstrong 1979). In doing so, the interest groups compared Bork’s record to those of sitting and departed justices, offering a comparison of approaches.

While the White House and interest groups had clear agendas with their briefing books, the letters that Senator Specter received were more varied and less straightforward in their language. Figure 5 shows the word cloud of the 300 most used words across the 72 constituent letters that Specter received. Compared to the clouds for the White House briefing books and the interest group briefing books, one thing is clear: fewer words stick out as obvious talking points. The words that are larger and toward the center of the cloud, like supreme, senate, and constitution, are generic terms one would expect to see in a letter about a Supreme Court nomination, and words like abortion and antitrust appear on the perimeters, suggesting these letter writers focused on many different issues. This is to be expected from small groups and individuals crafting letters to members of the Senate Judiciary Committee. The White House had a unified strategy and composed two informational documents for the Senate. Similarly, interest groups crafted equally strong documents that either enhanced or (mostly) fought the White House’s talking points. These groups have bright political strategists to compose cohesive messages. Alternatively, individuals write letters about topics that are significant to them. And Specter received letters from everyone, which means he got a variety of opinions, from those of law professors and practicing attorneys to average Joe Constituents.

The topics provided by the topic model suggest letter writers focused on varied content as well, as figure 3 shows. Again, we instructed the model to locate 15 topics, though this time, we left five of them out of the analysis because they were filled with jargon.[6] Some of the same topics appear in the letters that appeared in the briefing books, like Bork’s role in Watergate (something the interest groups ignored). But more importantly, these letters contain emotional elements. Constituents talk about the Democratic response to Bork; some offer criticism, and others offer support. They talk less about the facts, which the White House and interest groups discussed with such care, and focus more on the impressions left on them by the entire affair. The constituent letters provide different information than their formal counterparts, giving less explanation about Bork as a judge and more gut-feeling responses to the nominee himself.

| Topic | Keywords |

|---|---|

| Appointment and nomination | senate, president, nominee, committee |

| Bork’s decision-making history | opinion, decision, appeal, circuit |

| Separation of powers | branch, judicial, executive, power |

| Bork’s role in Watergate | attorney, special, Watergate, prosecutor |

| Organizations and groups | women, citizen, Congress, league |

| Legal groups | public, association, legal, fund |

| Constituent emotion and understanding | say, fact, know, wish |

| Emotions toward Bork | constituent, criticism, view, protection |

| Emotions tied to Democrats | left, democrat, want, hear |

| Expressions of support | support, will, position, decision |

Conclusion and Future Research

Writing in his memoirs in the early 2000s, Senator Arlen Specter recalled the impact that Senator Kennedy’s speech had on the Bork hearings, noting, “Kennedy crusaded against Bork. He rallied African-American ministers and leaders in the South. Hundreds of liberal organizations enlisted in the anti-Bork cause. Bork’s opponents launched a massive public relations campaign.…The idea was to poison public opinion against Bork, to influence and pressure senators.…The battle over Bork was so high-profile that it became almost compulsory for interest groups to join” (Specter and Robbins 2002, 321–22). In Specter’s view, Kennedy’s speech and later engagement with interest groups rallied those groups toward his cause. The Judiciary Committee found itself inundated with information from these groups, though Specter claimed that he remained above the raucous fray and approached the hearings like a lawyer would (Specter and Robbins 2002). Organized interests wanted to influence the senators and alter their behavior, and they were mobilized and energized in their fight.

During the Bork hearings, interest groups did everything from buying television ads to sending mass mailings to directly lobby senators to vote a certain way (Totenberg 2012). People for the American Way sent journalists and senators daily alerts about Bork’s nomination, and almost 40% of the nation’s full-time law faculty at accredited schools sent the Judiciary Committee letters saying Bork was unfit for a place on the Supreme Court (Specter and Robbins 2002). Less dramatically, interest groups also sent briefing books to the senators, providing them with summaries of the wealth of information that was available regarding Bork’s judicial philosophy and approach to certain types of cases. Bork’s distinguished career as an academic and judge—the very thing Reagan and his advisers thought would get him confirmed—created the longest paper trail through which senators had to that date tried to sort: 80 speeches, 30 law review articles, and 145 circuit court opinions (Specter and Robbins 2002). Anyone providing senators with information had to pick certain battles to fight—to highlight one section of Bork’s record over another—leading to briefing books that were anything but unbiased in their examination of Bork’s career.

Using Senator Arlen Specter’s personal papers, we examined the information provided by the people seeking to influence Specter’s vote on the Bork nomination. Specifically, we looked at the briefing books provided by the White House and liberal interest groups as well as a collection of letters sent directly to Specter from constituents and interest groups alike. Our goal was to identify what, exactly, was in those books and letters and how the content differed across senders. We found that organized groups—the White House and interest groups—sent factual information, while letter writers sent emotional appeals. The White House, first attempting to underscore Bork’s credentials and later attempting to rebut criticism of the judge, summarized that record in two briefing books they sent to senators (Davis 2017). Interest groups, mostly seeking to highlight the aspects of Bork’s record they deemed problematic, did the same, though, as our research shows, they covered different areas than the White House briefs. The letter writers, however, focused less on the substance of Bork’s record and more on their feelings about the nominee, based, at least in part, on the information the government and interest groups were pumping into the public sphere.

While our chapter is the first to use the information provided to senators to study informational appeals, our decision to use archival data also has limitations. First and most importantly, our analysis focuses on one hearing, and, as we discuss throughout this chapter, the Bork hearing was unique. Yet we exclusively focus on the Bork nomination because it had the most comprehensive set of nomination files in the Specter collection. Ideally, we would utilize a secondary data source, like another senator’s papers, to supplement the Specter papers and paint a more complete picture of nominations in the modern era. As we pointed out in the text, we are still waiting for the supplemental papers to appear, and our results are consequently bound to the nomination under study. In future work, we would like to supplement the Specter files with information from other sources as it becomes available.

Secondly, we see almost no information from conservative interest groups, leaving us to wonder how the right characterized the nomination and the nominee. The 23 groups that sent briefing books to Specter were liberal-learning groups like the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and the National Abortion Rights Action League (NARAL). While conservative groups like the National Conservative Political Action Committee did send Specter a letter, they did not provide a briefing book with summarized information about Bork’s record. Steigerwalt (2010) found that conservative groups were particularly lax in sending briefing books or background summaries to senators through the early 2000s, but anecdotal evidence suggests conservative groups got more involved, starting with the Roberts nomination in 2005 (Toobin 2008). Consequently, the only conservative opinions we could study were those of the Reagan administration. Eventually, as data allows, we want to look at nominations with more involvement from conservative groups.

Finally, we acknowledge the limitations that time places upon our research. We focused on the first “modern” Supreme Court confirmation hearing, the hearing that set the model for the way hearings work today, especially when it comes to interest group involvement (Cameron and Kastellec 2023). With that said, confirmation hearings have still changed since then—nominees are more polarized (Cameron, Kastellec, and Park 2013), the public increasingly views judges as ideological (Vining and Bitecofer 2023), senators’ votes are more partisan (Greenhouse 2021), and the Judiciary Committee engages in more tactical fighting than ever before (Calmes 2021), while more and more money pours into the process via ad campaigns (Marcus 2019). All of this suggests our findings might be modest compared to what we would find if we had access to the briefing books from more recent hearings, like those of now justices Amy Coney Barrett and Ketanji Brown Jackson. We hope that future scholars will be able to conduct similar analyses and build on our results.

Moving forward, the logical progression of this research is to compare the topics covered in the briefing books with the topics covered in a senator’s questioning. Specter, for example, mentioned that he spent two weeks doing his own research regarding Bork’s record and firmly believed the interest groups did not influence his approach to the nomination (Specter and Robbins 2002). Did his questions overlap with the information provided to him by interest groups? And if they did, how much overlap was there? These are the next questions to ask, and they encompass a promising avenue of future research.

Learning Activity

Interest Groups and Supreme Court Nominations

Learning Outcomes

- Students will be able to articulate the role that different actors have in the Supreme Court nomination process.

- Students will specifically learn about the role of interest groups in the nomination process.

- Students will practice researching and drafting thoughts on a swift timeline as well as the art of giving an “elevator pitch.”

Parameters of the Activity

- The instructor or teaching assistant performs the role of the “senator.”

- The instructor will inform students about the senator’s party.

- Students get sorted into their “interest groups.”

- This will depend on class size. The goal should be to have multiple “interest groups.” In a class of 15–20, the groups will need to be quite small, but in a larger class, they could be as large as 6–8.

- Each interest group gets a profile of their group’s platform and preferences.

- A list of potential interest groups for the instructor to use is available at the end of these instructions.

- It is important to have a balance of interest group perspectives represented in the classroom, so the instructor should predetermine which groups are available to students based on the class size.

- After settling into their interest groups, students will receive a profile of a Supreme Court nominee.[7]

- After reading about the nominee, students must decide if their group supports or opposes the nominee, develop an argument as to why, and then make their argument to the senator.

- Students have 10 minutes to draft their pitch and 3–5 minutes to make that pitch to the senator.

- Students should articulate whether the nominee should be confirmed from the perspective of their assigned interest group.

- The students should be expected to go beyond the given profile—that is, know why their group would support or be against the nominee. As research beyond the profile will be necessary, it would be wise to allow the use of technology during this activity.

- Students have the option to appoint a designated speaker or share the speaking responsibilities, but all students must work together in drafting the pitch.

- After all groups have presented, the senator will vote on whether to confirm the nominee or not based on which groups made the more convincing argument.

- Immediately following the activity, the instructor should tell the students why they voted the way they did, then get feedback from students about what they learned and the role of interest groups in the nomination process.

Nominee Profiles

Interest Group Profiles

Profiles taken from Vote Smart:

- NARAL Pro-Choice America

- National Institute for Reproductive Health Action Fund

- Center For Biological Diversity Action Fund

- Americans For Prosperity Action

- Patriotic Millionaires

- End Citizens United

- Brand New Congress

- Friends of Intelligent Democracy

- Liberty Guard

- Venn Institute

- 60 Plus Association

- National Association of Police Organizations

- Citizens United for Rehabilitation of Errants

- Moms Demand Action for Gun Sense

- Little Lobbyists

References

Abraham, Henry J. 2007. Justices, Presidents, and Senators: A History of the U.S. Supreme Court Appointments from Washington to Bush II. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Benoit, Kenneth, et al. “Quanteda: Quantitative Analysis of Textual Analysis.” Quanteda. http://quanteda.io/.

Caldeira, Gregory A., Marie Hojnacki, and John R. Wright. 2000. “The Lobbying Activities of Organized Interests in Federal Judicial Nominations.” The Journal of Politics 62(1): 51–69.

Caldeira, Gregory A., and John R. Wright. 1998. “Lobbying for Justice: Organized Interests, Supreme Court Nominations, and the United States Senate.” American Journal of Political Science 42(2): 499–523.

Calmes, Jackie. 2021. Dissent: The Radicalization of the Republican Party and Its Capture of the Courts. New York: Hachette Book Group.

Cameron, Charles M., Cody Gray, Jonathan P. Kastellec, and Jee-Kwang Park. 2020. “From Textbook Pluralism to Modern Hyperpluralism: Interest Groups and Supreme Court Nominations, 1930–2017.” Journal of Law and Courts 8(2): 301–32.

Cameron, Charles M., and Jonathan P. Kastellec. 2023. Making the Supreme Court: The Politics of Appointments, 1930–2020. New York: Oxford University Press.

Cohen, Lauren M. 1998. “Missing in Action: Interest Groups and Federal Judicial Appointments.” Judicature 82(3): 119–23.

Collins, Paul M., Jr., and Lori A. Ringhand. 2013. Supreme Court Confirmation Hearings and Constitutional Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Collins, Paul M., Jr., and Lori A. Ringhand. 2016. “The Institutionalization of Supreme Court Confirmation Hearings.” Law & Social Inquiry 41(1): 126–51.

Davis, Richard. 2017. Supreme Democracy: The End of Elitism in Supreme Court Nominations. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Epstein, Lee, René Lindstädt, Jeffrey A. Segal, and Chad Westerland. 2006. “The Changing Dynamics of Senate Voting on Supreme Court Nominees.” The Journal of Politics 68(2): 296–307.

Epstein, Lee, and Jeffrey A. Segal. 2005. Advice and Consent: The Politics of Judicial Appointments. New York: Oxford University Press.

Farganis, Dion, and Justin Wedeking. 2014. Supreme Court Confirmation Hearings in the U.S. Senate: Reconsidering the Charade. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Gibson, James L., and Gregory A. Caldeira. 2009. “Confirmation Politics and the Legitimacy of the U.S. Supreme Court: Institutional Loyalty, Positivity Bias, and the Alito Nomination.” American Journal of Political Science 53(1): 139–55.

Greenhouse, Linda. 2021. Justice on the Brink: The Death of Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the Rise of Amy Coney Barrett, and Twelve Months that Transformed the Supreme Court. New York: Random House.

Grimmer, Justin. 2013. Representational Style in Congress: What Legislators Say and Why It Matters. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Grimmer, Justin, and Brandon M. Stewart. 2013. “Text as Data: The Promise and Pitfalls of Automatic Content Analysis Methods for Political Texts.” Political Analysis 21(3): 267–97.

Hall, Richard L., and Alan V. Deardorff. 2006. “Lobbying as Legislative Subsidy.” American Political Science Review 100(1): 69–84.

Howard, Nicholas O., and Jason M. Roberts. 2015. “The Politics of Obstruction: Republican Holds in the U.S. Senate.” Legislative Studies Quarterly 40(2): 273–94.

Johnson, Timothy R., and Jason M. Roberts. 2004. “Presidential Capital and the Supreme Court Confirmation Process.” The Journal of Politics 66(3): 663–83.

Kagan, Elena. 1995. “Confirmation Messes: Old and New.” University of Chicago Law Review 62: 919–42.

Kaplan, David A. 2018. The Most Dangerous Branch: Inside the Supreme Court’s Assault on the Constitution. New York: Crown.

Kastellec, Jonathan P., Jeffrey R. Lax, and Justin Phillips. 2010. “Public Opinion and Senate Confirmation of Supreme Court Nominees.” The Journal of Politics 72(3): 767–84.

Kennedy, Edward M. 2009. True Compass: A Memoir. New York: Hachette Book Group.

Kirk, Michael, Mike Wiser, Jim Gilmore, Gabrielle Schonder, and Phillip Bennett. 2020. “Supreme Revenge: Battle for the Court.” Frontline. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/documentary/supreme-revenge/.

Kollman, Ken. 1998. Outside Lobbying: Public Opinion and Interest Group Strategies. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Krehbiel, Keith. 1998. “Supreme Court Appoints as a Move-the-Median Game.” American Journal of Political Science 51(2): 231–40.

Krutz, Glen S., Richard Fleisher, and Jon R. Bond. 1998. “From Abe Fortas to Zoe Baird: Why Some Presidential Nominations Fail in the Senate.” American Political Science Review 92(4): 871–81.

Lee, Frances E. 2009. Beyond Ideology: Politics, Principles, and Partisanship in the U.S. Senate. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lockman, Brian, and Francine Schertzer, eds. 2017. Arlen Specter: An Oral History. Camp Hill: Pennsylvania Cable Network.

Manning, Christopher D., and Hinrich Schutze. 1999. Foundations of Statistical Natural Language Processing. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Marcus, Ruth. 2019. Supreme Ambition: Brett Kavanaugh and the Conservative Takeover. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Mayhew, David R. 1974. Congress: The Electoral Connection. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Moraski, Bryon J., and Charles R. Shipan. 1999. “The Politics of Supreme Court Nominations: A Theory of Institutional Constraints and Choices.” American Journal of Political Science 43(4): 1069–95.

Nelson, Michael. 2018. “The Kavanaugh Hearings Could Shape the Supreme Court—Even If He’s Not Confirmed.” Washington Post Monkey Cage. https://wapo.st/2tiGt2M.

Nemacheck, Christine L. 2008. Strategic Selection: Presidential Nomination of Supreme Court Justices from Herbert Hoover through George W. Bush. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press.

Nobel, Kenneth B. 1987. “New Views Emerge of Bork’s Role in Watergate Dismissals.” New York Times, July 26, 1987. https://nyti.ms/2SMujuh.

Ramey, Adam J., Jonathan D. Klinger, and Gary E. Hollibaugh Jr. 2017. More Than a Feeling: Personality, Polarization, and the Transformation of the U.S. Congress. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Rice, Douglas. 2019. “Measuring the Issue Content of Supreme Court Opinions.” Journal of Law and Courts 7: 107–27.

Totenberg, Nina. 2012. “Robert Bork’s Supreme Court Nomination ‘Changed Everything, Maybe Forever.’” NPR. https://n.pr/2MXYzyN.

Rohde, David W., and Kenneth A. Shepsle. 2007. “Advising and Consenting in the 60-Vote Senate: Strategic Appointments to the Supreme Court.” The Journal of Politics 69(3): 664–77.

Scherer, Nancy. 2005. Scoring Points: Politicians, Political Activists, and the Lower Federal Court Appointment Process. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Scherer, Nancy, Brandon L. Bartels, and Amy Steigerwalt. 2008. “Sounding the Fire Alarm: The Role of Interest Groups in the Lower Federal Court Confirmation Process.” The Journal of Politics 70(4): 1026–39.

Schoenherr, Jessica A., and Ryan C. Black. 2019. “The Use of Precedent in U.S. Supreme Court Litigant Briefs.” In Elgar Research Handbook on Law and Courts, edited by Susan Sterrett and Lee Demetrius Walker. Edward Elgar.

Schoenherr, Jessica A., Elizabeth A. Lane, and Miles T. Armaly. 2020. “The Purpose of Senatorial Grandstanding during Supreme Court Confirmation Hearings.” Journal of Law and Courts 8(2): 333–58.

Smith, Steven S. 2007. Party Influence in Congress. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Specter, Arlen. 2018. “Arlen Specter Senatorial Papers, Group 2, Legislative Files, 1965–2011, TJU.2010.01.02.” Thomas Jefferson University (managed by the University of Pittsburgh Library System).

Specter, Arlen, and Charles Robbins. 2002. Passion for Truth: From Finding JFK’s Single Bullet to Questioning Anita Hill to Impeaching Clinton. New York: William Morrow.

Steigerwalt, Amy. 2010. Battle over the Bench: Senators, Interest Groups, and Lower Court Confirmations. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press.

Taylor, David Van. 2009 Advise and Dissent. Sundance Institute and Film Festival.

Toobin, Jeffrey. 2008. The Nine: Inside the Secret World of the Supreme Court. New York: Anchor Books.

US Courts. 2023. “Judgeship Appointments by President.” United States Courts Reports. https://www.uscourts.gov/sites/default/files/apptsbypres.pdf.

Vining, Richard L., and Rachel Bitecofer. 2023. “Change and Continuity in Citizens’ Evaluations of Supreme Court Nominees.” American Politics Research 51(1): 57–68.

Woodward, Bob, and Scott Armstrong. The Brethren: Inside the Supreme Court. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Anecdotal evidence suggests conservative interest groups got more involved in Supreme Court confirmation hearings around then judge John G. Roberts’s hearings in 2005 (Taylor 2009), with them playing an especially prominent role during now justice Brett Kavanaugh’s nomination in 2018 (Nelson 2018). Cameron and Kastellec (2023) suggest conservative and liberal interest groups’ involvement in the hearings increases over time to the point of near evenness, with Bork’s confirmation hearing being the catalyst for this change. ↵

- Three other senators’ papers would also be ideal for this project—those from Joe Biden, Orrin Hatch, and Ted Kennedy. All three sat on the Judiciary Committee around the same time as Specter and were some of its most senior members. Democrats Biden and Kennedy would have received information from liberal-leaning interest groups seeking to influence a nomination, and Hatch, a Republican who showed a willingness to vote for Democratically nominated judges like Ruth Bader Ginsburg, would have also been a target. None of their papers are available, however. Biden is currently serving as the forty-sixth president of the United States, while Brigham Young University and the JFK Library are still processing Hatch’s and Kennedy’s papers, respectively. ↵

- Specifically, our data came from Specter’s Legislative Files (Group 2 in the collection), where we focused on the “Nominations, 1965–2010” collection, which is located in the “Committee on the Judiciary, 1965–2010” files (Series 1, Subseries 3); see Specter 2018. ↵

- The Specter archives made national news when an ESPN reporter visited them while investigating President Donald Trump’s intervention in the New England Patriots’ “Spygate” scandal. If you are curious, check out the story here: https://bit.ly/43NZVns. We promise you will not regret it! ↵

- Bork was well known for his 1978 book The Antitrust Paradox, which criticized the United States’ antitrust law. Antitrust law focuses on the promotion of competition in the marketplace and the prohibition of monopolies. ↵

- ABBYY FineReader had a difficult time turning the letters into analyzable text. The briefing books from the White House and interest groups were well constructed, with groups producing beautifully typed books that Senator Specter and his team did not mark up. For the most part, turning the original documents into readable text was easy for these types of documents. Constituent letters were a different story, however. The letters had typos, ink smudges, and uneven spacing, making some of them difficult to read and process. Moreover, Specter and his staff clearly read these letters, as they contained handwritten notes and even, in a few instances, what looked like part of Specter’s lunch mushed into the page. Clearly, no one expected researchers to come through 30 years later and try to digitize the text on these letters. Consequently, we ended up with more noise—random letters appearing, other letters disappearing, words that did not match one another—in this part of the analysis than we had in the other parts. ↵

- The following nominee profile images are in the public domain ↵