Court Procedures

22 Judicial Discretion and U.S. Supreme Court Agenda Setting

Elizabeth A. Lane; Jessica A. Schoenherr; Rachel A. Schutte; and Ryan C. Black

The scene is familiar to anyone who has watched a movie or read a book about a lawsuit: the sympathetic protagonist loses his case, and his attorney promises him they still have one more chance to win. The attorney then shoves his files into his briefcase, storms out of the courtroom, and announces to the waiting crowd (filled with reporters) that they will be taking their case “all the way to the Supreme Court!” Attorneys representing Barbara Grutter, a forty-three-year-old white woman aiming to enter the University of Michigan Law School, found themselves in a less-dramatic version of this exact position following their loss before the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals. Grutter sued the law school for using a race-based admissions policy that she claimed discriminated against her and therefore violated her rights under the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment (Morfin et al. 2006; Perry 2007). Like many litigants in modern history, Grutter and her attorneys turned to the Supreme Court in a last-ditch effort to find a favorable resolution to her case. Yet the odds of the Court hearing the case were long. Despite growing demand for the Court’s attention on constitutional issues, the justices deny review to 99 percent of the litigants who ask the Court to consider their cases (Lane and Black 2017). Grutter’s appeal made it past the cut, however, and the Court agreed to hear arguments in her case, now known as Grutter v. Bollinger (2003).

Why did the Court agree to hear Grutter’s case but not somebody else’s? One possible answer to this question is that the justices saw an opportunity to move policy closer to their preferences (Black and Owens 2009a; Caldeira, Wright and Zorn 1999). Supreme Court justices are not simply motivated by the law; like other political elites in Washington, they have policy preferences and want to use their powerful positions to move policy toward their ideal points (Epstein and Knight 1998). When a justice considers whether to grant review in a case, she thinks about the future and considers how the final outcome on the merits can shift policy and if that policy will be closer to her preferences (Black and Owens 2009a; Caldeira, Wright and Zorn 1999). With affirmative action in higher education, for example, the Court had already ruled in Regents of the University of California v. Bakke (1978) that race was a permissible consideration in admission decisions because schools had a compelling interest in ensuring diversity in classes. Given this explanation, conservative justices might have anticipated they had the chance to overturn or weaken Bakke, a ruling with which many of them disagreed, and thus they finally agreed to review law school admission policies in Grutter (Toobin 2008).

A more legalistic explanation of the justices’ decision is the presence of conflict. The Supreme Court has a duty to ensure universal interpretation of the law throughout the country, which means stepping in when the lower courts disagree (C-SPAN 2010; Ulmer 1984). Despite the Court’s original ruling in Bakke, circuit courts struggled to implement the decision in the face of lawsuits from angry students who felt they lost their spots at dream schools to less-qualified minority candidates. The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, which covers federal appellate cases in Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi, ruled in Hopwood v. Texas (1996) that the law school at the University of Texas lacked a “compelling justification” for using affirmative action (Burka 1996). Further west, the massive Ninth Circuit, which oversees district courts in California, Oregon, Washington, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Arizona, Alaska, and Hawaii, ruled in Smith v. University of Washington Law School (2000) that the University of Washington Law School’s affirmative action admissions program met the Bakke standard (Gearan 2001). The Sixth Circuit’s ruling in favor of the University of Michigan Law School in Grutter added to the conflict, and the cacophony might have pushed the Court to finally agree to review one of these affirmative action cases and resolve the problem.

A third possible explanation is that Grutter’s case was important and the justices therefore felt obligated to weigh in on it. Just as the Court has an obligation to ensure uniformity in the law, it also has a responsibility to answer unsettled legal questions that the public considers important (Perry 1991). Affirmative action programs undoubtedly met that requirement. Universities’ decisions to consider race in admissions were controversial when the justices decided Bakke in 1978, and they remain controversial today (Coyle 2013). Even if the justices failed to notice public attention toward the issue, they still knew the case was important because Grutter’s petition came with a signal attached to it: three different interest groups filed amicus curiae (“friend of the Court”) briefs in the Grutter case. These briefs described how a decision in this case would extend far beyond Barbara Grutter and the University of Michigan Law School, impacting states, law schools, and employers who all had an interest in knowing if affirmative action programs were constitutional. The fact that interest groups and public interest law firms dedicated time and resources to submitting these amicus briefs before the Court even agreed to hear Grutter’s case sent a powerful signal that this case was important enough to deserve the justices’ attention.

In this chapter, we set out to explain the Supreme Court’s agenda-setting process and then examine the roles that policy, the law, and organized interests can play in influencing the justices’ decisions in that process. The Supreme Court has a discretionary docket, allowing the justices to select the cases they want to hear (Perry 1991). The justices have agreed to hear fewer cases since the late 1980s, but the shrinking docket has not stopped litigants from appealing to the Court in record numbers (Lane and Black 2017; Owens and Simon 2011). The end result of this mismatch is a mound of petitions through which the justices must sort each term. Litigants and interest groups can attract the justices’ attention by sending cues about a case’s ideological impact, its involvement in a lower court conflict, or its importance. After walking through the process and explaining what research shows to be true about it, we narrow our focus to one particular part of the process: interest groups’ submission of amicus briefs that support or oppose a petitioner’s request for review. We use new data to show that interest group participation in agenda setting can influence the Court’s ultimate decision to hear a case, confirming Caldeira and Wright’s (1988) seminal work on agenda setting and signaling in the process. Finally, we end our analysis by offering our thoughts about where the literature can go from here.

Setting the Supreme Court’s Agenda

History

Supreme Court justices have not always had a say in the cases they review. Article III of the Constitution established the Supreme Court and outlined the limited circumstances under which the Court could act as a trial court, which hears testimony and makes factual determinations. The founders intended the Supreme Court to mostly act as an appellate court, which focuses on questions of law, but the Constitution gave Congress the power to determine the Court’s appellate jurisdiction. Originally, Congress required the justices to hear every case appealed to them, but that caseload grew to be unmanageable, and after some polite urging by Chief Justice Fuller, Congress agreed in 1891 to give the justices some discretion over their docket (Sternberg 2008). In the thirty years that followed, the caseload quickly returned to unwieldy status, driving Justice McReynolds and Chief Justice Taft to plead with Congress to give the Court more discretion over its docket (Stevens 1983). Congress subsequently passed the Judiciary Act of 1925, which required all plaintiffs appealing to the Supreme Court to file petitions for the writ of certiorari (Latin for “to be more fully informed”). These petitions request that lower court documents be sent to the High Court, along with a legal brief describing why their case is worthy of the justices’ review (Perry 1991). When the Court’s docket reached historic highs in the 1970s and 1980s, all nine justices wrote to Senator Kastenmeier and asked for even more discretion over the Court’s docket. Congress again provided it, removing virtually all of the Court’s mandatory jurisdiction via the Case Selections Act of 1988 (Owens and Simon 2011).

As the justices gained more autonomy over their agenda, they established two rules to govern their decision to grant review in a case. The first is Supreme Court Rule 10, originally established in 1954. Rule 10 lists the circumstances under which the justices are more likely to grant review in a case, specifically when one of the following occur: (1) conflict between lower courts, whether it is between two circuit courts or between a state court of last resort and a circuit court; (2) conflict between a state supreme court or circuit court and a past Supreme Court decision; and (3) an important matter of federal law that has not previously been addressed by the Supreme Court. Rule 10 is purposefully vague, but it provides the litigants with direction about the information worth highlighting in their petitions (Perry 1991). The second rule governing the decision to grant certiorari, more commonly known as “cert,” is the Rule of Four, established by the Judiciary Act of 1925 (Cordray and Cordray 2004). According to this rule, the justices place a case on the docket if four of the nine justices vote to grant review. The Rule of Four is the only countermajoritarian act in which the Court engages. Of course, securing four votes to grant cert is very different from securing a five-vote majority on the merits, which leads to the justices engaging in forward-looking behavior when deciding whether to review (Black and Owens 2009a; Caldeira, Wright and Zorn 1999).

Process

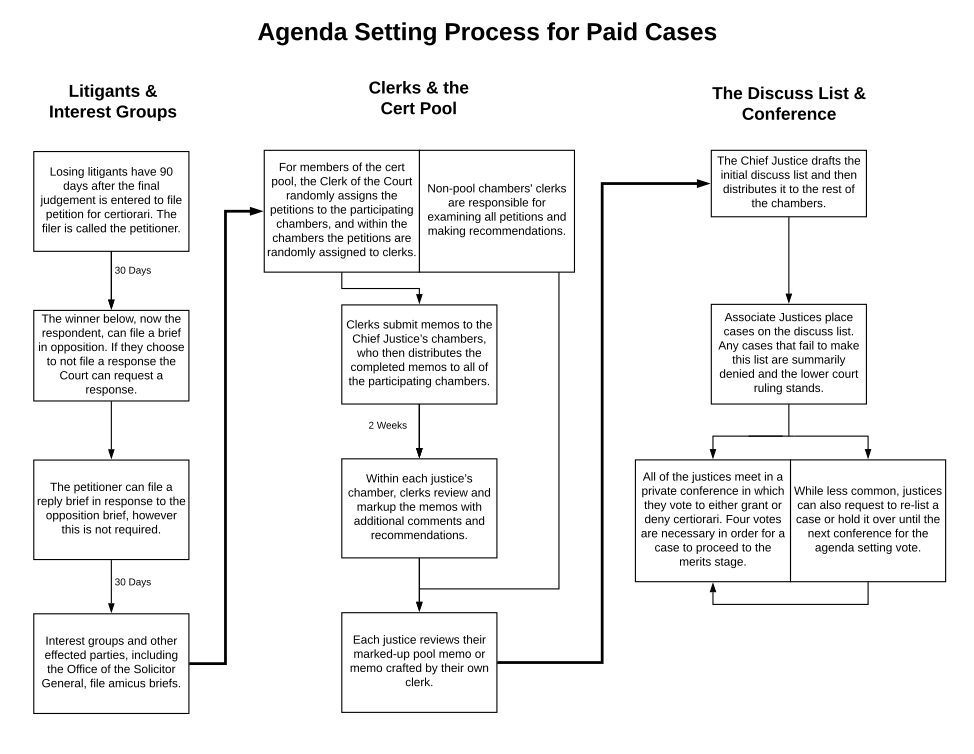

The agenda-setting process begins with somebody losing a case involving a federal issue in either a federal circuit court or a state court of last resort. After losing, litigants have the opportunity to appeal to the Supreme Court if they so choose; if they decide to petition the Court to review the case, they file a petition for certiorari, as shown in the top left corner of Figure 1. Here the litigant, now known as the petitioner, writes an explanation of how his or her case meets the Rule 10 requirements and requests all case documents from the lower court be sent to the Supreme Court for review. After the petitioner files the documents with the Court, the lower court winner, now known as the respondent, has the opportunity to respond to the petition for certiorari by writing a brief in opposition and explaining why the justices should pass on this particular case. During the filing and responding stage, interest groups can file amicus curiae briefs, also known as “friend of the Court” briefs, that offer support for or opposition to the petitioner’s request.

Once the petitioner and respondent have submitted all their materials to the Clerk of the Court, the Clerk is responsible for distributing all case materials to the chambers so that each justice can begin the review process. As the middle section of Figure 1 shows, the Clerk goes through two different distribution processes. Most of the justices participate in the cert pool, meaning they “pool” their collective resources to make it through the thousands of cert petitions the Court receives each term (Perry 1991). Rather than ask each chamber to review every cert petition individually, the Clerk of the Court randomly assigns each cert petition to one of the participating justices’ chambers, and that justice then assigns the petition to one of his or her law clerks (Ward and Weiden 2006). These law clerks are recent graduates of elite law schools who spend a year of their lives working as legal aides to the justices (Black, Boyd and Bryan 2014). The law clerk responsible for the petition drafts a pool memo that reviews the petition, discusses the “certworthiness” of the case, and makes a recommendation to either grant or deny review. After drafting a pool memo, the law clerk submits it to the Chief Justice’s chambers, where it is then redistributed to each participating justice for review and markup (Black and Boyd 2011). Alternatively, justices can remain out of the cert pool, in which case the Clerk distributes every cert petition to those justices for their own review. As of the October 2018 term, Justices Alito and Gorsuch do not participate in the pool, so they (or their law clerks) must review every petition submitted to the Court and identify certworthy cases on their own (Mauro 2018).

The justices make their first decisions regarding the agenda-setting process when they receive the cert memos and their accompanying documentation. After reading through a cert memo, the justices decide if they personally want the full Court to formally consider that cert petition. Cases that a justice deems worthy of conversation get added to the “discuss list,” which, as its name implies, is a list of all the cases the justices will eventually discuss and vote at conference. As shown by the third and final section of Figure 1, the Chief Justice starts the list and circulates it. An associate justice can add any cases he or she feels the Chief missed, but no justice can remove a case once it appears on the list. Any case that does not appear on the discuss list is summarily denied review and the lower court’s ruling stands. Making it onto the discuss list is the first step toward making it to the Supreme Court, though few litigants realize this, as the justices guard the discuss list and refuse to publicly release it (Perry 1991).

The justices go through the discuss list and identify the cases worth reviewing at their weekly conference (Perry 1991). While seniority typically dictates who speaks first on an issue, that is not always the case when it comes to cert petitions; the justice who placed the case on the discuss list leads the conversation about it. After talking about each petition, the justices vote to grant or deny review, starting with the Chief, then going around the conference table in order of seniority (Black and Owens 2012c). According to the Rule of Four, if a case receives four votes, the justices will schedule it for oral arguments. If a case does not get four votes to grant review or three votes to grant and a neutral “join-three” vote,[1] the justices deny review and the lower court’s ruling stands. The final step of the agenda-setting process is the release of the order list, the official document announcing each petition’s resolution. Cases that failed to make the discuss list and cases that failed to garner four votes in favor of review all go under the populous “Certiorari Denied” section, while all petitions that made it off the discuss list and onto the docket get listed under “Certiorari Granted.” The order list does not disclose the justices’ conference vote regarding any case. The only method of releasing these votes in real time is if a justice releases a dissent from denial of cert. Dissents from denial have increased in frequency in recent terms but are still uncommon.

The order list is the only public record that exists of the justices’ agenda-setting decisions. From the minute the petition reaches the Clerk to the morning the justices release their order list, all decisions regarding cert petitions take place under a veil of secrecy. The justices are firm that clerks cannot take materials outside of the building or talk to the press about the Court’s proceedings, and the justices forbid anyone other than the nine from entering their conference room (Woodward and Armstrong 1979). Consequently, no one sees the discuss list or sees how the justices voted on a cert petition in real time. Besides dissent from denial, the only way the discuss list or conference votes are disclosed is through the release of justices’ personal papers. The availability and accessibility of archival data, specifically from Justice Harry A. Blackmun, transformed research and the public’s understanding of the agenda-setting process (Lane and Black 2017).

The Decision to Grant Review

Starting with the 2000 term, the justices and their clerks review, on average, about 150 cert petitions a week and about 8,000 petitions a term. They narrow these 8,000 petitions down to the 500 cases that make the discuss list and then narrow those 500 cases down to the 80 or so that make the Court’s agenda (Lane and Black 2017).[2] Even with clerks’ help, the justices spend a considerable amount of time reviewing cert petitions while still trying to fulfill their other courtly duties. Justice Scalia colorfully described the time-consuming task as “undoubtedly, to my mind, the most, what shall I say, onerous and, for the most part, uninteresting part of the job” (C-SPAN 2010), and Justice O’Connor compared the task to doing exercise every day (Ward and Weiden 2006). The justices consequently look for ways shorten the time it takes to make it through the mountain of petitions they receive. They know what makes a case certworthy—policy, legal conflict, and importance—but they need help finding certworthy cases in the noise of so many petitions. Cues or informational shortcuts that can be found in petitions are proven valuable resources, and litigants and interest groups can help send these signals (Tanenhaus et al. 1963).

First and foremost, petitioners grab the justices’ attention by offering them a case that will advance their ideological interests in the long term (Perry 1991). Supreme Court justices are, after all, motivated in large part by their policy preferences; more specifically, they are motivated by their ability to influence the Court’s final merits decision (Epstein and Knight 1998). The justices watch for cases that are “good vehicles” for change and they are more likely to grant review to those types of cases (Perry 1991). Supreme Court justices ask themselves if a case will help them move policy in their preferred direction (Black and Owens 2009a, 2012c; Caldeira, Wright and Zorn 1999). This is because the justices are forward thinking and attempt to see how their cert vote will play out at the merits stage, given they make a decision on the merits with the help of the eight other justices (Black and Owens 2009a, 2012c; Caldeira, Wright and Zorn 1999). So, for example, a conservative justice will not want to vote to grant review on a case if he expects the liberals will win on the merits and move the policy further from what he thinks it should be. In this scenario, he is better off voting to deny review and let a liberal decision stand for one circuit as opposed to the entire country if the Supreme Court were to rule.

Although justices are motivated by their ideology, they are not simply politicians in robes. Legal and institutional factors do influence agenda-setting decisions and can constrain the justices’ behavior (Perry 1991). First and most obviously, the justices follow their own rules and look for the presence of lower court conflict when they evaluate petitions (Stern et al. 2002). Attorneys consequently seek to identify the conflict in their case, alleging in their petition that it exists in order to get the justices’ attention. At the same time, however, the justices and clerks can also investigate these claims and the magnitude of the conflict (Black and Boyd 2013). Past research has found that the presence of legal conflict is one of the strongest predictors of a case being granted review (Black and Owens 2009a; Caldeira and Wright 1988; Caldeira, Wright and Zorn 1999; Schoenherr and Black 2019). In fact, the presence of conflict can even increase the likelihood that a justice who would otherwise be ideologically predisposed not to grant cert casts a grant vote in that case.

The justices also consider the parties involved in a case, especially when the US government is involved. When the federal government appears as a petitioner, the justices are significantly more likely to place a case on the discuss list and eventually grant it review (Black and Owens 2011; Black and Owens 2012a). The Solicitor General, who represents the United States before the Court, is often referred to as the “Tenth Justice” because of his expertise and frequent participation at the Marble Palace (Black and Boyd 2012; Caplan 1988; Wohlfarth 2009). The justices have a general trust in the Office of the Solicitor General at the agenda stage because he is selective, meaning he only brings the best cases to the justices for their review (Bailey, Kamoie and Maltzman 2005; Black and Owens 2012b; Perry 1991; Zorn 2002). Even when the United States is not a party to the case, the justices might call for the views of the Solicitor General (CVSG) and ask him to weigh in on a case’s certworthiness (Anders 2017; Black and Owens 2012a; Thompson and Wachtell 2009). The Solicitor General’s involvement sends a bright signal to the justices about a case’s potential for making the docket.

The number of amicus briefs filed at the agenda stage is another strong predictor of whether a case appears on the discuss list and also on the Court’s agenda. These briefs signal the vast importance of the answer to the legal question(s) raised by the case. The signal’s strength comes, at least in part, from the group’s willingness to endure the cost associated with amicus briefs. Amicus participation is intimately tied to a group’s funds; interest groups with larger budgets are more likely to submit amicus briefs than are groups with less money to use (Solberg and Waltenburg 2006). Amicus briefs are costly enterprises for outside interests, and these groups will therefore only sacrifice resources when they have a vested interest in the outcome (Caldeira and Wright 1988; Schoenherr and Black 2019). These briefs consequently send a strong signal to the justices that a case deserves their consideration. Amicus briefs filed by the Solicitor General send a particularly strong signal about a case’s importance (Bailey, Kamoie and Maltzman 2005; Black and Owens 2012b), suggesting that combining some of these signals increases their magnitude.

The justices evaluate these cues differently depending on the stage of the process, however. As Black and Boyd (2013) explain, the justices look for low-cost cues about a case’s certworthiness when considering it for the discuss list. The justices are more likely to place a case on the discuss list if a circuit court judge published a dissent in the case, if conflicts exist in the lower court’s record, if the Solicitor General gets involved in a case, or if interest groups file amicus briefs regarding the petition for certiorari (Black and Boyd 2013). They are also less likely to place a case on the discuss list if the circuit court did not publish its decision or if the district and circuit courts sided with the same party (Black and Boyd 2013). The justices begin their review by looking for basic facts that might indicate the case is interesting to them.

When the justices evaluate whether cases should move from the discuss list to the docket, they change their evaluation strategy. The justices are less dependent on low-cost, low-information cues at this point (Black and Boyd 2013), at least in part because they have the time to evaluate petitions more closely when they only have ten or so a week to consider (Baum 2015). They instead pay more attention to high-information cues. While the presence of conflict (weak or strong) influences the likelihood that a case makes the discuss list and the docket, the effect is larger at the docket stage, when the justices have time to confirm the strength of the conflict (Black and Boyd 2013). The same is true for other high-information cues, such as the presence of the Solicitor General in a case and the number of amicus briefs submitted with the petition (Black and Boyd 2013).

The general substantive point we want to make here is that there are two stages in the Court’s agenda-setting process: the creation of the discuss list and the final agenda-setting vote. In the pages and eventual quantitative analysis that follows, we opt to focus on the final decision to grant or deny review conditional on the fact that a case has already made it to the discuss list. We do so for both substantive and practical reasons. In terms of substance, the question of interest is whether a case is granted review. Some are; most are not. This variation is what ultimately influences the content of law. Simply making it on the discuss list is a necessary but not sufficient condition. One might wonder, why not simply consider both at the same time? This is a great observation, but for the scope of the chapter, please take us at our word that what seems to be a straightforward tweak would open up a colossal can of worms that we seek to avoid.[3]

Amicus Briefs and Agenda Setting

As the previous section suggests, a multitude of factors can influence the justices’ decision to grant review in a case. In the empirical analysis that follows, we focus on one of the many: amicus briefs submitted before the Court agrees to hear a case. We do this because everything we understand about agenda setting and signaling, from low-cost name recognition to high-cost validation of conflict, stems from a seminal piece by Caldeira and Wright (1988) about amicus briefs and agenda setting. Caldeira and Wright suggested that interest groups can signal a case’s importance by filing an amicus brief alongside a litigant’s petition for certiorari. Importantly, it does not matter if the brief supports the petitioner or opposes the petitioner—any filing by an interest group increases the likelihood of the Court granting cert. The signal is what Black and Boyd (2013) later call a low-cost, high-information cue; it is easy for the justices to see that someone filed an amicus brief at the agenda-setting stage, and its presence provides the justices with information about the petition’s importance. Amicus briefs submitted during the agenda-setting stage are powerful because they initially appear illogical—interest groups have limited time and resources to spend on amicus briefs (Hansford 2004), so they typically wait for a case to make the docket before they put together a brief. If organized interests invest their time and resources into a case before the Court has even put it on its agenda, however, then they must be doing so because the case is that important. Just as the justices pay attention to the existence of conflict when reviewing cert petitions, they also pay attention to a case’s importance. So, do amicus briefs send this signal to the justices? Our research question is simple: Does the number of amicus briefs submitted in a case at the agenda-setting stage increase the likelihood the Court agrees to hear that case?

As Black and Boyd (2013) point out, amicus briefs influence the justices most when they are considering moving a case from the discuss list to the docket. That is, research shows that amicus briefs exert their largest influence when a case is already on the discuss list; when justices are curating the list, they are more likely to consider low-cost, low-information cues, such as the presence of conflict or lower-court dissent. For the sake of this study, then, we restrict our focus to the potentially certworthy cases and examine the cases that made the discuss list. Of course, studying anything involving the discuss list requires obtaining a copy of said list, and the Court does not release information about it. As we mentioned previously, however, scholars have successfully used the justices’ private papers to collect discuss lists and study agenda setting (Black and Boyd 2012; Black, Boyd and Bryan 2014; Black and Owens 2009a; Epstein, Segal and Spaeth 2007; Schoenherr and Black 2019). Justice Harry Blackmun’s papers, specifically, are the papers that most scholars use. Blackmun, who served on the Court from 1970 to 1994, meticulously documented his life as a member of the Court and saved everything, which he donated to the Library of Congress (Greenhouse 2005). Epstein, Segal, and Spaeth (2007), armed with a National Science Foundation grant, digitized the papers from the 1986 to 1993 terms and made this treasure trove of internal documents (including discuss lists) available to the masses. As Black and Owens explain, the Blackmun papers “offer an unprecedented view of the Supreme Court’s agenda-setting decisions” (2009b, 254), and scholars have taken full advantage of the offerings to better understand how the Court sets its agenda (Black and Owens 2009a, b; Black and Boyd 2013; Schoenherr and Black 2019). Following in that tradition, we use Black and Owens’s (2009a) agenda-setting data for our analysis. The data set covers a random sample of 360 paid, non–death penalty petitions from the federal courts of appeals that made the discuss list between the 1986 and 1993 terms.[4]

Our dependent variable is a dichotomous indicator of the Court’s announced decision to grant or deny review in a case. The variable takes the value of 1 if the Court grants review in the case and takes the value of 0 otherwise. Because this variable can only take two possible values, we use probit models for our analysis (Long 1997).

Our key independent variables are the number of amicus briefs filed (1) in favor of the petitioner and (2) in favor of the respondent at the agenda-setting stage. This means we believe that each additional amicus brief will increase the likelihood of the Court granting review.

Because we want to focus on amicus briefs’ influence on agenda setting, we also have to consider other factors that could influence the justices’ decision to grant review. That is to say, we have to control for all the factors we discussed in the previous section in our model. We do this by including variables for conflict (alleged, weak, and strong), Solicitor General involvement, lower court conflict, and case importance as signaled by amicus briefs. Table 1 lists the control variables that we employ as well as how we measure them, how the literature suggests they should influence the likelihood the Court agrees to review the case, and what our research finds to be statistically significant.

| Variable | Measurement | Hypothesized Direction | Significant Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alleged Conflict | Coded as 1 if the petitioner’s mentions conflict between two lower courts or a lower court and the Supreme Court. | + | No |

| Weak Conflict | Coded as 1 if the petitioner alleges conflict, but the clerk discounts the actuality of this conflict in his memo. | + | No |

| Strong Conflict | Coded as 1 if the petitioner alleges conflict and the clerk agrees this conflict exists in his memo. | + | Yes |

| U.S. Supports | Coded as 1 if the United States is a petitioner in a case or files an amicus brief supporting review. | + | Yes |

| U.S. Opposes | Coded as 1 if the United States is a respondent in a case or files an amicus brief in opposition to review. | – | Yes |

| Appellate Reversal | Coded as 1 if the last court to hear the case reversed the previous court’s ruling. | + | Yes |

| Appellate Dissent | Coded as 1 if a dissent was authored by a judge in the lower court. | + | No |

| Law Unconstitutional | Coded as 1 if the lower court strikes down a federal statute as unconstitutional. | + | Yes |

| En Banc Panel | Coded as 1 if the lower court decision is reviewed by the entire circuit in an en banc review. | + | No |

| Appellate Unpublished | Coded as 1 if the lower court did not publish an opinion on their decision. | – | No |

| U.S. Law Week Coverage | Coded as 1 if the circuit court’s decision is mentioned in U.S. Law Week. | + | No |

| Ideological Congruence | Supreme Court median’s Judicial Common Space score if the lower court’s ruling was liberal. Inverse of the Supreme Court median’s Judicial Common Space score if the lower court’s ruling was conservative. | – | No |

| Petitioner Amicus Briefs | Count of the number of amicus briefs filed in support of review. | + | Yes |

| Respondent Amicus Briefs | Count of the of amicus briefs filed in opposition to review. | + | Yes |

Results

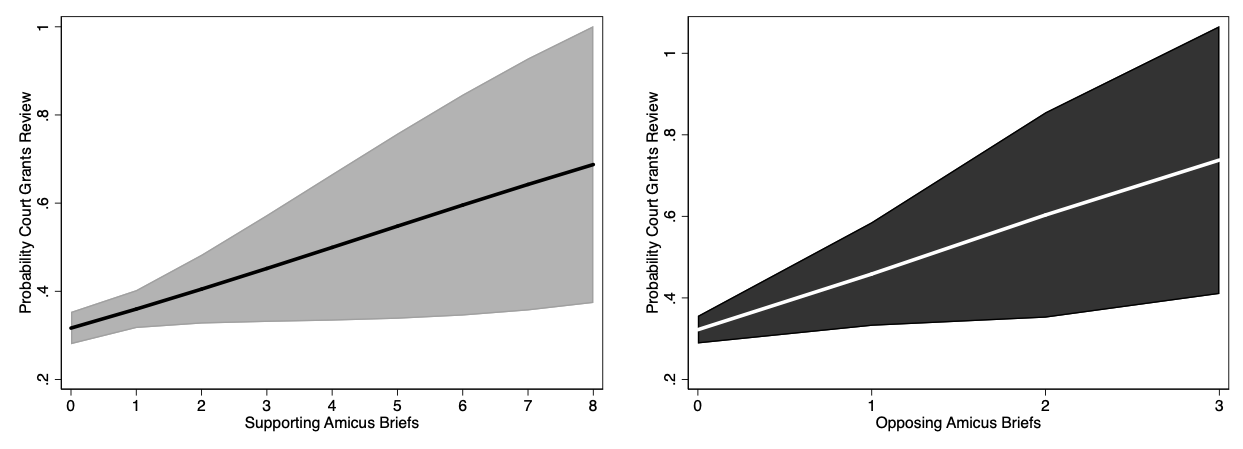

With the content of our model explained, we turn now to examining the model estimates to learn more about how amicus briefs influence the Court’s decision to grant review. The table of coefficients can be found in the appendix. Because our model is nonlinear, we used maximum likelihood estimation techniques, which produce coefficients that are difficult to interpret on their face (Long and Freese 2006). We thus use predicted values to aid us in interpretation. Figure 2 addresses the probability the Court will grant review in a case as the number of amicus briefs filed in support of the petitioner (top) and in opposition to the petitioner (bottom) increases.

On the horizontal axis of Figure 2 is the number of amicus briefs filed supporting and opposing the petitioner, respectively. The vertical axis shows the estimated probability the Court will grant a petition review. Turning first to the top of Figure 2, the line illustrates that the more briefs filed in support, the higher the likelihood the Court will grant review in a case. The most common value in our data set is for a petition to have no supporting amicus briefs, with 83 percent of the petitions we examine falling into this category. These petitions have a 32 percent chance of being granted review. If you move right along the horizontal axis and examine petitions with a single brief in support of it, you see that likelihood increases to 36 percent, and the likelihood of being granted review continues to increase with each additional amicus brief. A petition with five supporting amicus briefs, which is in the ninety-ninth percentile of our sample data, has a 55 percent chance of being granted review by the Court. Importantly, notice that as you move from left to right on the graph, the shaded area that surrounds the line gets wider, which indicates less precision in our results. This is because most of the cases in our data set (83 percent) go to the justices without a single amicus brief attached to them, while only about 1 percent of cases went to the justices with four or more amicus briefs attached. Essentially, we have less data to help explain the Court’s behavior, so we are less able to distinguish our results. Even with this imprecision, however, these results suggest that as more interest groups show interest in a case by filing briefs, the justices are more likely to hear the case.

The line running through the graph on the bottom half of Figure 2 shows how the probability of the Court granting review in a case changes as the number of amicus briefs opposing the petitioner increases. Interestingly, we see the same trend that we saw in the top half—the more amicus briefs filed in opposition, the more likely the Court is to grant review. While a case with no amicus briefs attached to it has a 32 percent chance of being granted review, a case with a single opposing amicus brief has a 46 percent (31 percent, 61 percent) chance of review. Importantly, a single-brief increase for opposing briefs has a larger magnitude than the one for supporting briefs. The relative effect of a single-brief increase for an opposing brief is about 44 percent, while a single-brief increase for a supporting brief is only 12 percent. On the whole, Figure 2 suggests that filing an amicus brief at the agenda-setting stage increases the likelihood the Court grants review in a case regardless of the brief’s support or opposition of the petitioner. In short, we show that amicus briefs influence the likelihood the Court moves a case from the discuss list to the docket and that the more amicus briefs there are, the better the chance of making that happen.

But what do these results mean more generally and in comparison with other factors that we and previous research have identified as being important? Recall our opening case anecdote, which involved the plight of the would-be law student, Barbara Grutter. At the onset, we posited three possible explanations for the Court’s ultimate decision to grant review in the case. There were politics: a conservative-leaning court wanted a chance to reconsider a liberal legal status quo. There were legal considerations: the federal courts of appeals had arrived at conflicting answers on the question of whether incorporating racial preferences in admissions was constitutional. And last, there was the aspect we have devoted quite a few words to in the preceding pages—namely, the underlying policy importance of the case.

The chief benefit of adopting an otherwise complex statistical approach such as we have done here is that it allows us to examine a host of explanations at the same time. Table 1 gives a summary of these results, and Table 2 in our appendix provides the full tale of the tape for those who like looking at lots of numbers. As for what these values mean for our three candidate explanations, they allow us to say a number of things. First, the results of our study provide only limited support for the role of ideological considerations. To assess this, we looked at the level of agreement (or disagreement) between the median Supreme Court justice and the ideological direction of the lower court’s decision. If ideology mattered, then we would expect that liberal-leaning courts would want to review (and probably reverse) conservative lower court rulings. The empirical results fall in something of a statistical no-man’s-land. By this, we mean they are not strong enough to confidently say that an effect exists, but at the same time, we would be uncomfortable shouting from our ivory towers that ideology is not a factor. We realize this is not terribly satisfying. Welcome to science. What we think this should mean for how you understand Supreme Court agenda-setting is that ideology is not the only factor that matters. We suspect other chapters in this book will come to the same conclusion—or at least they should because, well, that is the right answer.

If it is not all ideology, then what about the law? Legal factors matter. A lot. Big time. The presence of a clear legal conflict within the court system is the single most important factor with respect to the chance of a case being granted review. A typical case in our data has roughly a one-in-three chance of being selected. This typical case does not have clear legal conflict in it. If we use our magic wand and “give” conflict to this typical case, however, we would predict that the likelihood of review would jump—nay, skyrocket—to 69 percent. That’s right, sports fans, it would more than double. As for the underlying importance of the case, we already gave you those numbers a few paragraphs ago, but in case you forgot, a case that is super-duper (highly technical) important has about a 55 percent chance of being selected for review. That ultimately means that although policy importance is quite important, it still takes the silver medal compared to the undisputed heavyweight champion of the world, the law. Importance fought the law and, as the song suggests, the law won—but not by a lot.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court’s process of selecting cases for its dockets is complicated, with only the strongest (or most appealing) cases making it onto the Court’s agenda. Clerks and justices review petitions to build a short list of cases, and then the justices review them again before finally selecting the cases they want to hear. They look for lower court conflict, for signals of confusion among lower court judges, for known entities like the Solicitor General to vouch for a petitioner, and for interest groups to help signal a case’s overall importance. The entire process occurs behind a curtain of secrecy, with the public only ever seeing the final result of “Certiorari Denied” (for most cases) and “Certiorari Granted” (for the lucky 1 percent). Yet there are certain tools that interested parties—the petitioners and organized interests, specifically—can use to make their case stand out to the justices. One of those tools, as we show here, is filing amicus briefs in support of or opposition to a cert petition. Such an action signals a case’s importance to the justices, and they respond to the cue (Caldeira and Wright 1988). Supreme Court justices are more likely to move a case from the discuss list to the docket if it has amicus briefs filed alongside the cert petition.

When Caldeira and Wright (1988) originally examined this phenomenon, they were some of the first to write about signaling theory and its importance to the agenda-setting process. They pointed out that the justices need help sorting through the thousands of cases to find the good ones and that interest groups can help the justices do that. Later work suggested that litigants could do the same (Baird 2004; Black and Boyd 2012a; Perry 1991), including specific information in their cert petitions that could attract a justice’s attention while simultaneously burying the information that could hurt it. While all these signals are obviously important (and we control for their presence in our analysis because research shows they all matter), we turned our analytical focus to amicus briefs because they are the external signals of a case’s importance. Obviously, litigants want to show the justices why they need to hear a case; in fact, it is a requirement that they explain a case’s certworthiness to the justices when they file an amicus brief (Stern et al. 2002). Amici, on the other hand, have no obligation to speak, and their voluntary action makes them worthy of discussion and additional attention.

One limitation to our work here, which actually stems from the necessity of using archival data, is the time-bounded nature of the results. We have eight terms’ worth of discuss list data, but those eight terms’ worth of data are at least twenty-five years old. Since 1993, the Court has lost and replaced seven members and dealt with a deluge of cert petitions that reached an all-time high of more than ten thousand in the 2006 term (Lane and Black 2017). If the Court has undergone any institutional changes since 1993 that affected the agenda-setting process, scholars cannot study them until another justice releases his or her papers. Given many of the current justices’ advanced age, this might not look like a problem, but recent justices have voiced a strong preference for releasing papers long after they have left the Court (Mauro 2016; Watts 2013). Some scholars, such as Feldman and Kappner (2016), work around this problem by studying the information in the cert petitions and the order lists, which can provide interesting descriptive information about agenda setting. Hypothesis testing is more challenging, however, as determining whether legal conflict exists is time consuming. Of course, as more papers become available (Justice Souter’s will be available fifty years after his death, for example; see Mauro 2016), future scholars can study the current Court much like we analyzed the Rehnquist Court here.

Another limitation of our work, and all work in this area, is that it neglects one of the most important aspects of review: the lower court’s opinion. While scholars can typically identify the direction of a lower court’s opinion, they understand very little about its content. Can judges write opinions in a way that insulates them from review—the same way Supreme Court justices write opinions to avoid congressional interference (Owens, Wedeking and Wohlfarth 2013)? Anecdotal evidence suggests the justices do not worry about review (Songer, Sheehan and Haire 2000), but other work suggests judges care about their standing in the profession and with their peers (Baum 2010) and therefore should seek to avoid review and consequent embarrassment. Future work should address the content of the lower court’s opinion, if judges are writing in a way that avoids review, and if the justices understand the signal.

The Supreme Court agenda-setting process is one of the most interesting and least understood parts of the Court’s overarching process. As Clarence Thomas once explained, many people think they have a right to present their cases to the justices (C-SPAN 2010), and people do threaten early on to fight their case “all the way to the Supreme Court,” as the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) did in 2013 when former basketball players filed a class-action lawsuit against them for using their likenesses in video games (Le 2013). But as the NCAA discovered in 2016, Supreme Court justices decide which cases they want to hear, and most cases end before ever reaching the justices’ ears. Society has high expectations for the Court’s capacity to hear cases, but in reality, the justices are incredibly selective about the cases that actually end up on their docket. Because the justices make these decisions in private, they do little to help the public understand this process. Thankfully, archival research and data analysis like those employed in this chapter can help unwrap this mystery and provide context for when the justices might agree to hear certain cases.

So why are amicus briefs so worthy of study? Because they offer external groups the chance to influence a uniquely insular process. Supreme Court cases involve a surprisingly limited number of people—the parties to the case, their attorneys, and the nine justices—and the justices make their decisions based on the specifics of the case. But those specifics lead to opinions, and those opinions contain legal reasonings that apply to everyone, not just the parties involved (Clark and Lauderdale 2010; Hansford and Spriggs 2006). When Barbara Grutter sued the University of Michigan, she sued to get herself admitted to the school. But when the Court announced its decision in Grutter v. Bollinger (2003), the decision impacted the millions of students applying to college each year too. Understandably, then, outside interests want their needs considered when the justices hear a case. Of course, interest groups cannot voice their needs if they do not have a case in which to do it. We study amicus briefs submitted at the agenda-setting stage because they show that external interests can (and do) influence the Supreme Court’s processes too, right down to which cases the justices decide to hear in the first place. True, the parties certainly have their reasons for wanting the justices to hear a case, but noting that outside interests do as well is important for understanding how the Court goes about its work.

Learning Activity

Agenda-Setting Simulation: Writing Assignment

- Using twelve-point font and double spacing, your paper should be three to four pages long. It should be well written using appropriate grammar and correct spelling. You must produce a works cited page that conforms to the APSA Style Manual for Political Science: https://connect.apsanet.org/stylemanual/wp-content/uploads/sites/43/2018/11/Style-Manual-for-Political-Science-2018.pdf. This includes using in-text parenthetical citations! You must cite the source where you’ve found your information, whether you are using quotation marks to indicate a direct quote or paraphrasing someone else’s argument. If you have any questions about plagiarism, see your instructor before the assignment is due because any academic honesty violation will result in an automatic zero.

- This does not need to adhere to a typical essay structure. You will not need to include an introduction or conclusion. Your paper should be divided into four primary sections (for consistency, use the headings in bold in your paper).

Sections

- Biographical background: This will be the shortest section of your paper that highlights where the justice is from and any other information that you deem relevant (e.g., religious affiliation or marital status).

- Legal background: In this section, you are to highlight relevant work experience. Where did he or she get her law degree? What was he or she doing before becoming a justice? What year did he or she join the Court? What president nominated the justice and what was the Senate confirmation like?

- General approach to the decision-making: This is the meat of the assignment and will likely be longer than the preceding sections. Your description should include some direct quotations from the justice’s own writings, on and/or off the bench. Your critical evaluation should include some comparative references—that is, some discussion of how your justice’s understanding of the Court’s role differs from the understanding of some other justices.

- Check out this list of speeches by a number of the justices available here: http://www.supremecourt.gov/publicinfo/speeches/speeches.aspx

- And this handy tool for finding opinions written by particular justices: http://www.law.cornell.edu/supct/justices/opinions.html

- And this site, which compiles materials on recent nomination hearings for the justices: http://www.loc.gov/law/find/court-confirmed.php

- Some questions you might consider in this section: Does the justice favor judicial restraint or is he or she an activist? (You will encounter these things in your research, so a good scholar would make sure to define what this means.) Does a justice prefer deference to majoritarian political institutions or is he or she more inclined to protect minority rights? Does the justice adhere to the original intent of the framers or does he or she view the Constitution as a living document that must change with the times? How closely does the justice follow precedent?

- Ideological predisposition: This ties in directly with the analysis in the preceding section. That is, in the previous section, you discuss how a justice claims to make decisions, while in this section, you assess whether the justice is observationally a political conservative, liberal, or moderate justice on the Court. In other words, how does a justice’s voting behavior tie into his or her judicial philosophy? Is this justice’s vote consistent with the president that nominated him or her, or were there surprises in the justice’s behavior after he or she joined the bench? Who are your justice’s most usual allies on the Court?

In Class

- To get credit, you must be in class.

- The class will be divided into five separate Supreme Courts that correspond to the group number on the assignment sheet.

- At the start of class—roughly the first fifteen to twenty minutes—you will have an opportunity to tell the rest of your “Court” about the justice you are assigned to play. You should be prepared to highlight the most important information.

- Next, you will be given a stack of writs of certiorari to review. Your job will be to (1) determine whether it’s in the best interest of the justice to grant review in the case, (2) convince the other justices of your position, (3) listen to the views of your colleagues, and finally, (4) vote on the treatment of the cert petition.

Agenda-Setting Simulation Class Activity

Materials from summaries and analyses are available on SCOTUSblog.com and directly from actual writs of certiorari and response briefs.

- Divide into your assigned Supreme Courts.

- Spend no more than fifteen minutes introducing your assigned justice to the other members of the Court. It would be helpful if you sat in a circle in descending order of seniority, clockwise from the Chief Justice’s left: Chief Justice Roberts followed by Justices Thomas, Ginsburg, Breyer, Alito, Sotomayor, Kagan, Gorsuch, and Kavanaugh. You might wish to also make a name tag to help your colleagues remember who you are.

- Take a quick look at the structure of this cert petition packet to familiarize yourself with its layout.

- Each case contains a brief statement of facts, the basic arguments of the parties, the holding of the lower courts where applicable, and the questions/issues before the Supreme Court.

- Each case is followed by a docket sheet, where you will note your vote selections. In the “Defer” category, you may elect to “Relist” the case, which functionally holds the case for another discussion, or you may CVSG, which is calling for the views of the Solicitor General when you think the federal government should weigh in. In the “Cert.” category, you could choose to grant (G), deny (D), or grant, vacate, and remand (GVR).

- It is on this docket sheet that each one of you should record the vote selections for every member of your Court. Beneath the table, there is space for you to justify your own vote choice. That is, you are justifying the Court’s decision, but you are explaining why you / your justice voted the way you did.

- Before you vote and write your justification, discussion should proceed as follows:

- Everyone should read the very short case summary / cert petition.

- The chief justice should then ask if everyone understands the basics of the case. At this point, you are functioning not as justices but as student colleagues, so puzzle through any questions that arise together.

- Then you should discuss the case. At the Supreme Court, this happens in descending order of seniority, and you might wish to loosely follow that structure here. Each of you should talk in every case. As you’re debating, consider the following: what your justice would sincerely want the outcome of this case to be, whether your justice is likely to prevail on the merits, and if the case satisfies Rule 10 and presents a legal conflict or an important unsettled question of law. Your job should be to convince your colleagues of your viewpoint.

- Once discussion is concluded, take a formal vote in descending order of seniority. Then write a couple of sentences about why you voted the way you did, noting whether it was a sincere or strategic choice and why.

- On the bottom of the page, determine as a group what happened to your case. Was it granted? Denied? Something else?

- Write your name and that of your justice on the front of this packet and submit the entire thing at the end of class.

Case Summaries

Blagojevich v. United States

Docket no.: 17-658

Lower court: Seventh Circuit

Basic Facts / Relevant Precedent

Petitioner Rod Blagojevich was convicted of eighteen crimes, including corruption and fraud, all committed while he was the governor of Illinois. The district court sentenced him to 168 months’ (fourteen years) imprisonment. Blagojevich appealed his sentence to the circuit court on the grounds that (1) the sentence was excessive for the crimes committed (i.e., there were no violent offenses, and Blagojevich contends that he will be meaningfully rehabilitated in less time) and, more importantly, (2) the government did not prove that the defendant made an explicit promise in exchange for a campaign contribution.

The circuit court first remanded the case back to the district court to ask them to consider whether the sentence was appropriate. The district court reaffirmed the initial sentence, and Blagojevich went back to the circuit court. This time, the circuit court upheld the lower court’s sentence and took up the burden of proof question. The Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals used the precedent set in McCormick v. United States (1991) and joined two other circuits to require “only . . . that a public official has obtained a payment . . . knowing that [it] was made in return for official acts” rather than siding with five circuits that use the precedent set in Evans v. United States (1992), which holds that the government must prove the defendant made an “explicit promise or undertaking” in exchange for the contribution.

Petitioner’s Main Arguments

The precedent set in Evans, which is a newer and more relevant case, should control in government corruption cases, as the preponderance of circuits hold. The government failed to reach that exacting burden of proof. Additionally, there is a clear circuit split that only the Supreme Court can reconcile.

Justice demands that like cases are treated alike. A sentence of fourteen years for nonviolent crimes is inconsistent with nationwide trends for white-collar and/or political crimes. Only two circuits—the seventh and the tenth—decline to hear defendants’ requests for lesser sentences to avoid “unwarranted sentence disparities.”

Respondent’s Main Arguments

There is valid precedent (see McCormick) to use a lower burden of proof when there is evidence that a public official abused his or her power in office. The sentence does not exceed federal sentencing guidelines, and there is no official law that requires any court to conform to national sentencing trends, so it is within the court’s power to decline the defendant’s request to consider whether there’s a sentencing disparity.

Issues before the Supreme Court

- Clarify whether McCormick or Evans is controlling precedent in corruption cases. In particular, what burden of proof does the government bear? Does it need to prove that the public official explicitly traded political favors for a campaign contribution, or is it sufficient that the public official knows that the donation was made in expectation of favorable political treatment?

- Can a district court decline to address a defendant’s nonfrivolous argument that a shorter sentence is necessary to avoid “unwarranted sentence disparities” for crimes of a similar nature?

Procedural History

The Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals sided with the government and against Blagojevich twice.

| Defer Relist |

Cert. CVSG |

G | D | GVR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roberts, Ch. J. | |||||

| Thomas, J. | |||||

| Ginsburg, J. | |||||

| Breyer, J. | |||||

| Alito, J. | |||||

| Sotomayor, J. | |||||

| Kagan, J. | |||||

| Gorsuch, J. | |||||

| Kavanaugh, J. |

Justification for vote choice:

Cert petition outcome: _______________________________________

Carpenter v. United States

Docket no.: 16-402

Lower court: Sixth Circuit

Basic Facts / Relevant Precedent

In United States v. Miller (1976), the Supreme Court ruled that bank records of a man accused of running an illegal whiskey-distilling operation were not obtained in violation of the Fourth Amendment even though law enforcement officials did not have a warrant because the bank records contained “only information voluntarily conveyed to the banks and exposed to their employees in the ordinary course of business.” Three years later, in Smith v. Maryland, the justices ruled that no Fourth Amendment violation had occurred when, without a warrant and at the request of the police, the phone company installed a device to record all the phone numbers that a robbery suspect called from his home, leading to his arrest.

These cases are cited as examples of the “third-party doctrine”—the idea that the Fourth Amendment does not protect records or information that someone voluntarily shares with someone or something else. But does the third-party doctrine apply the same way to cell phones, which became commercially available after those precedents were set?

Timothy Carpenter was accused of being the mastermind behind a series of armed robberies in Ohio and Michigan. Law enforcement officials asked cell phone providers for Carpenter’s phone records, relying on the Stored Communications Act of 1986, which allows phone companies to disclose records when the government provides reasonable cause to believe that the phone has been used to commit a crime. Using several months of phone records, investigators linked Carpenter’s cell to towers in the vicinity of the robberies.

At his trial, Carpenter argued that the police should have obtained a warrant for his phone records because he had a reasonable expectation of privacy. Therefore, those records should not be admitted as evidence. The district court disagreed and allowed the phone records to serve as key evidence in the trial, which ultimately resulted in a conviction of 116 years in prison. Carpenter appealed to the Sixth Circuit Court, where he lost.

Petitioner’s Main Arguments

On appeal to the Supreme Court, Carpenter is supported by various privacy interest group amicus curiae briefs, and all contend that the old rules are outdated for this technological age. In particular, people carry their cell phones everywhere, including in the home, where the Court has consistently ruled that people have a reasonable expectation of privacy. The data about a person’s whereabouts are not voluntarily given, the petitioner argues, because it happens automatically whenever the phone is turned on.

Respondent’s Main Arguments

The government argues that the old rules apply no matter the technological innovation. There’s precedent and statutory law to support the lower court’s treatment of evidence obtained without a warrant, and there is no Fourth Amendment violation.

Issue before the Supreme Court

- Does the warrantless search and seizure of historical cell phone records, revealing the location and movements of a cell phone user over the course of 127 days, violate the Fourth Amendment?

Procedural History

Both the district and circuit courts relied on the “third-party doctrine” and the Stored Communications Act to conclude that the search was legal and did not require a warrant.

| Defer Relist |

Cert. CVSG |

G | D | GVR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roberts, Ch. J. | |||||

| Thomas, J. | |||||

| Ginsburg, J. | |||||

| Breyer, J. | |||||

| Alito, J. | |||||

| Sotomayor, J. | |||||

| Kagan, J. | |||||

| Gorsuch, J. | |||||

| Kavanaugh, J. |

Justification for vote choice:

Cert petition outcome: _______________________________________

Missouri et al. v. California

Docket no.: 220148

Original jurisdiction of the US Supreme Court

Basic Facts / Relevant Precedent

Together with twelve other states, Missouri is suing the state of California over regulations on the treatment of farm animals. In this case, Missouri contends that California imposes stricter regulations on the treatment of chickens than federal law requires, which in turn has the effect of inflating “egg prices for every egg consumer in the nation.” California’s law requires that farms raising egg-laying hens must ensure that the chickens are able to move around freely. California counters that its law impacts only farms and eggs sold within the state’s borders and should not have an impact on chickens in Missouri or anywhere else in the nation. Missouri and the other states argue that California doesn’t exist in a vacuum, and when the price of eggs goes up in California, the price goes up throughout the rest of the country. Additionally, California sends inspectors to other states if farmers sell their eggs in California, which the petitioners contend violates state sovereignty.

This is similar to a second case on appeal to the Supreme Court, Indiana v. Massachusetts, where another group of thirteen states (not identical to the first group of state plaintiffs in the first case) challenges a Massachusetts law that imposes similar restrictions by barring sales within that state of eggs, pork, and veal from animals that were “confined in a cruel manner.” Like California, Massachusetts argues that its law applies only to sales within the state’s geographical territory and therefore does not violate any federal laws or the US Constitution.

In both the Missouri and Indiana cases, the petitioners are filing suit directly with the Supreme Court under its original jurisdiction (because remember, when one [or more] state sues another, the Supreme Court acts as a trial court). California argues that Missouri should sue in a federal district court, but the respondents fail to identify what district court would have jurisdiction over such an interstate dispute. Missouri goes a step further to argue that the Supreme Court must take the case because the Constitution doesn’t specify that the Court has discretion over such cases (and that there is an absence of federal law giving the Court discretion over its original jurisdiction, unlike the Supreme Court Case Selection Act of 1988, which gives the Supreme Court almost unlimited discretion over its appellate jurisdiction).

The petitioners assert that the California and Massachusetts laws violate the Commerce Clause of the Constitution, which gives Congress the exclusive authority to regulate interstate commerce. Because these farm restrictions trigger higher prices everywhere, the plaintiffs argue, California and Massachusetts are unfairly impeding interstate commerce.

Issues before the Supreme Court

- Does this case fall under the Supreme Court’s original jurisdiction?

- Does the Supreme Court have discretion to opt out of hearing cases filed under its original jurisdiction?

- Does California’s (and Massachusetts’s) law regulating the treatment and sale of farm animals and their products violate the Commerce Clause of the US Constitution?

| Defer Relist |

Cert. CVSG |

G | D | GVR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roberts, Ch. J. | |||||

| Thomas, J. | |||||

| Ginsburg, J. | |||||

| Breyer, J. | |||||

| Alito, J. | |||||

| Sotomayor, J. | |||||

| Kagan, J. | |||||

| Gorsuch, J. | |||||

| Kavanaugh, J. |

Justification for vote choice:

Cert petition outcome: _______________________________________

Azar v. Garza

Docket no.: 17-654

Lower court: DC Circuit

Basic Facts / Relevant Precedent

A seventeen-year-old pregnant woman was caught at the US-Mexico border trying to enter the United States illegally. She was held in a detention facility where she had a medical exam that confirmed she was pregnant. “Jane Doe” tried to schedule an abortion, but the Trump administration blocked her request, which prompted a lawsuit in federal court.

On appeal to the US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, which had jurisdiction in this case, on October 24, a full panel of judges cleared the way for Doe to obtain an abortion. The circuit court remanded the case to the district court, where the judge declared that Doe should be allowed to have an abortion “promptly and without delay.” Doe’s abortion was scheduled for October 26 after receiving counseling on October 25; pursuant to Texas law, she had undergone one counseling session on October 19.

The Trump administration, represented by Solicitor General Noel Francisco, planned to submit a petition to the Supreme Court to ask the Court to issue a hold to delay Doe’s abortion until the Court could hear arguments in the case. Rather than give the federal government time to file a writ of certiorari, Doe and her legal team changed her abortion appointment to October 25 without informing the federal government of their plans. The solicitor general filed suit at the Supreme Court on October 26.

Petitioner’s Main Arguments

The petitioner in this case is the Trump administration, presented by the office of the solicitor general. They are asking the Supreme Court to vacate the DC circuit’s decision so that it does not set precedent even within that specific circuit. In particular, the petitioners argue that the federal government has a vested interest to avoid facilitating abortions. The government asked the Supreme Court to do two things: First, it urged the justices to vacate the DC circuit’s ruling in favor of Jane Doe and to instruct the DC circuit to send the case back to a federal trial court, where that district court would have to dismiss the claims relating to “the government’s treatment of a pregnant unaccompanied minor” because Jane Doe is no longer pregnant. That is the correct answer, contends the petitioner, because the government’s efforts to appeal the DC circuit’s decision became moot as a result of the conduct of Doe’s lawyers.

Second, the government suggested that the Supreme Court could take the additional step to “discipline” Doe’s attorneys for misleading the federal government about when Doe would obtain an abortion, which led to the delay in the filing of their cert petition so that there was no chance for the federal government to block the abortion.

Respondent’s Main Arguments

Doe is represented by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), and her lawyers argue that their job was to “see that she wasn’t delayed any further . . . [and they] acted in the best interest of [their] client in full compliance with court orders and federal and Texas law. That the government lawyers failed to seek judicial review quickly enough is their fault, not ours.”

Issues before the Supreme Court

- Since Doe is no longer a pregnant illegal alien, should this case be dismissed as moot and the lower court’s decision thereby vacated?

- Did Doe’s attorneys have a legal duty to inform the federal government when the abortion was to occur? Given their failure to do so, should the ACLU be subject to disciplinary action?

Procedural History

The DC Circuit and the district court on remand sided with Doe and held that illegal immigrants (including minors) were entitled to constitutional protection.

| Defer Relist |

Cert. CVSG |

G | D | GVR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roberts, Ch. J. | |||||

| Thomas, J. | |||||

| Ginsburg, J. | |||||

| Breyer, J. | |||||

| Alito, J. | |||||

| Sotomayor, J. | |||||

| Kagan, J. | |||||

| Gorsuch, J. | |||||

| Kavanaugh, J. |

Justification for vote choice:

Cert petition outcome: _______________________________________

National Institute of Family and Life Advocates v. Becerra

Docket no.: 16-1140

Lower court: Ninth Circuit

Basic Facts / Relevant Precedent

In 2015, California lawmakers enacted the Reproductive Freedom, Accountability, Comprehensive Care, and Transparency (FACT) Act. The act responded to concerns that crisis pregnancy centers—nonprofit organizations, often affiliated with Christian groups that are opposed to abortion—were posing as full-service reproductive health clinics and providing pregnant women with inaccurate or misleading information about their options.

The act imposes two different sets of requirements. Nonprofits that are licensed to provide medical services (such as pregnancy tests and ultrasound examinations) must post notices to inform their patients that free or low-cost abortions are available and provide the telephone number of the state agency that can put the patients in touch with providers of those abortions. Centers that are not licensed to provide medical services—but try to support pregnant women by supplying them with diapers and formula, for example—must include disclaimers in their advertisements to make clear, in up to thirteen languages, that their services do not include medical help. California’s attorney general and local government lawyers can sue facilities that don’t comply with the law; the penalty is a $500 fine for the first offense and $1,000 for any later violations.

Petitioner’s Main Arguments

The centers are represented by lawyers for the Alliance Defending Freedom, which also played key roles in (among others) two recent high-profile cases: Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission, the case of a Colorado man who says that requiring him to create custom cakes for same-sex weddings would violate his religious beliefs, and Zubik v. Burwell, a challenge by religious nonprofits to the workarounds offered to those who objected to the Affordable Care Act’s birth control mandate. They argue that the Ninth Circuit should have used the most stringent test—known as “strict scrutiny”—to review the FACT Act’s constitutionality because the law is based on the content of the centers’ speech and discriminates based on their viewpoint.

When that standard is used, the petitioners contend, the law cannot survive. It places enormous burdens on the centers even though California has not provided any evidence suggesting that the centers are actually causing any harm, and it applies to all pregnancy centers even if they are not doing anything misleading. If the state were truly concerned that pregnant women aren’t getting information about state-funded options, the centers conclude, it could publicize that information itself.

Respondent’s Main Arguments

California counters that the act targets two problems: women who can’t afford medical care aren’t aware of the publicly funded options available to them, and when they go to these centers, they are often confused about whether they are getting care and advice from medical professionals. The notices that the medical centers are required to provide, the state argues, fall “well within the First Amendment’s tolerance for the regulation of the practice-related speech of licensed professionals.” And the notices that the unlicensed centers must provide, the state continues, are permissible to prevent confusion about the nature of their care.

Issue before the Supreme Court

- Whether the disclosures required by the FACT Act violate the protections set forth in the free speech clause of the First Amendment, applicable to the states through the Fourteenth Amendment.

Procedural History

The district and circuit courts agreed with the state of California and found that the FACT Act did not violate the First Amendment.

| Defer Relist |

Cert. CVSG |

G | D | GVR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roberts, Ch. J. | |||||

| Thomas, J. | |||||

| Ginsburg, J. | |||||

| Breyer, J. | |||||

| Alito, J. | |||||

| Sotomayor, J. | |||||

| Kagan, J. | |||||

| Gorsuch, J. | |||||

| Kavanaugh, J. |

Justification for vote choice:

Cert petition outcome: _______________________________________

Evans v. Mississippi

Docket no.: 17-7245

Lower court: Mississippi Supreme Court

Basic Facts / Relevant Precedent

Timothy Evans is a lifelong alcoholic. Upon release from a state penitentiary for a felony conviction of driving under the influence, Evans moved in with his ex-girlfriend, Wenda Holling. Evans made attempts at employment, but he was an unreliable employee even when working for friends. As a result, he was unemployed and relied entirely on Holling for financial support.

On New Year’s Day 2010, Evans and Holling got into an argument when Holling said she would no longer subsidize Evans’s drinking problem. Evans strangled Holling to death, concealed her in the trunk of her car, and disposed of her body in an isolated place in a neighboring county, where it was discovered weeks later. Meanwhile, Evans told Holling’s family that she was on vacation in Florida, but he actually stole Holling’s car and drove to Florida himself, where he used her credit cards to purchase gasoline, food, and lodging. Upon the discovery of Holling’s body, police tracked the credit card usage in Florida, found Evans, and arrested him. He confessed to the murder and the theft.

A unanimous jury convicted him of robbery-based felony capital murder. The prosecution sought the death penalty, and the same jury delivered that sentence a couple hours after delivering the guilty plea.

Petitioner’s Main Arguments

The petitioner contends that the sentence is unconstitutional because the fact that Evans “is sitting on death row . . . is a product primarily of geographic accident.” The criminal court that controls where Evans committed his crime imposes the death penalty at a substantially higher rate than any other court in the state. The petitioner argues that this is evidence that the death penalty is arbitrarily applied within the state; were it not, the death penalty should be proportionately applied across the state for the same types of crimes.

The petitioner relies on various Supreme Court precedents to emphasize the historical focus on the seriousness of such a sentence. They also provide evidence that there is “widespread [national] consensus against the death penalty,” pointing to the fact that thirty-one states have either formally or in practice abandoned the practice. Moreover, 85 percent of executions in the last five years are concentrated in five states: Texas, Oklahoma, Florida, Missouri, and Georgia. A majority of those are issued in only a handful of counties. All of this, according to the petitioner, suggests that this creates inconsistencies and injustice in the application of the death penalty, which is no longer viable under the Constitution’s Eighth Amendment protections.

Respondent’s Main Arguments

The Supreme Court has current precedent that allows states to determine whether the death penalty is a permissible sentence. The state of Mississippi is acting in accordance with established Constitutional law. This is a state’s rights issue. It doesn’t matter, then, how frequently or infrequently the death penalty is across the nation.

Issue before the Supreme Court

- Does the death penalty in and of itself violate the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition of cruel and unusual punishment in light of the contemporary standards of decency and the geographic arbitrariness of its imposition?

Procedural History

The Supreme Court for the State of Mississippi denied a rehearing, affirming the sentence and declining to review the federal question about the constitutionality of the death penalty.

| Defer Relist |

Cert. CVSG |

G | D | GVR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roberts, Ch. J. | |||||

| Thomas, J. | |||||

| Ginsburg, J. | |||||

| Breyer, J. | |||||

| Alito, J. | |||||

| Sotomayor, J. | |||||

| Kagan, J. | |||||

| Gorsuch, J. | |||||

| Kavanaugh, J. |

Justification for vote choice:

Cert petition outcome: _______________________________________

Dassey v. Dittmann

Docket no.: 17-1172

Lower court: Seventh Circuit

Basic Facts / Relevant Precedent