Court Procedures

24 Evaluating Regime Support Groups and Judicial Independence

Denise Saenz and Rebecca A. Reid

Introduction

Judicial independence is considered a cornerstone of democracy, where independent courts effectively safeguard civil rights and liberties through their impartial decision making (Howard and Carey 2004), constrain government power (Shapiro 1981; Henisz 2000), and protect against democratic backsliding (Gibler and Randazzo 2011). Much of the judicial independence scholarship identifies how the establishment of judicial independence depends on ruling elites’ desire to ensure they stay in power (Sievert 2018; Aydın 2013; Finkel 2008; Helmke and Rosenbluth 2009; Popova 2010; Hirschl 2001; Ramseyer 1994). Yet the ability to stay in power depends on winning coalition(s) supporting these ruling elites. Ruling elites, or the government leaders in power, differ in their reliance on specific groups of people from whom they need continued support to stay in power, called winning coalitions (Bueno de Mesquita et al. 2003). Hence we investigate the question, Do high courts’ degree of judicial independence depend on the identity(s) of the winning coalition(s)? In other words, we explore how who composes the winning coalition influences judicial independence. By offering an exploratory quantitative analysis, we contribute to a greater understanding of the political contexts within which judicial independence is promoted and offer future avenues for research.

Winning Coalitions, Political Survival, and Judicial Independence

The primary goal for any ruling elite is to stay in power. Their ability to stay in power is determined by two groups: the winning coalition and the selectorate (Bueno de Mesquita et al. 2003). The selectorate consists of everyone in a country’s population who has a say in determining the ruling elite. In democracies, for example, the selectorate consists of all registered voters. A winning coalition, however, is a subgroup of the selectorate whose support is necessary for political victory. For example, a winning coalition may consist of security forces, the military, business oligarchs, or any subset of people upon whom the ruling elite relies. The identity and size of winning coalitions vary across regimes. For example, winning coalition(s) in democracies are usually large and closely resemble the entire selectorate. For autocracies, winning coalitions tend to be small and exclusive, such as business elites or security forces. The identification of winning coalitions is important because each winning coalition generates incentives and requirements for the ruling elite to stay in power. These incentives can differ drastically based on the level of dependence, size, and composition of the winning coalitions. For instance, democracies with large and diverse winning coalitions have incentives to provide public goods to satisfy voters and thereby stay in power via reelection. Autocratic leaders with small winning coalitions instead face incentives to provide private goods to satisfy their small group of supporters. For example, if an autocratic leader’s winning coalition consists of business elites or oligarchs, then they have incentives to provide economic benefits to enrich these specific individuals, so they continue to support the leader—not necessarily provide economic benefits to the population as a whole. In short, winning coalitions identify who the ruling elite depends on and determine the policy incentives of those in power.

A ruling elite’s desire to stay in power is a fundamental component in theories regarding the establishment of judicial independence. Judicial independence is defined as autonomous decision making, where judges are protected from external political pressures so they can render decisions independently, autonomously, and without political pressure or threat (Linzer and Staton 2015). The establishment of judicial independence depends on whether and to what extent judicial independence benefits the ruling elite in power. For example, previous studies have identified a variety of benefits provided by judicial independence, such as enhancing legitimacy (Ginsburg and Moustafa 2008), improving administrative compliance (Moustafa 2014), reducing corruption (Ginsburg and Moustafa 2008), facilitating coordination across government branches (Vanberg 2015), resolving information problems (Sievert 2018), protecting government policies and ousted leaders once removed from power (Aydın 2013; Finkel 2008), enhancing economic development (Feld and Voigt 2003; Moustafa 2008), and improving social control and order (Tate and Vallinder 1995). These benefits can make judicial independence desirable to ruling elites, even though they must pay the cost of sometimes facing undesirable court decisions. Thus, judicial independence is not an end unto itself; rather, it is a means to an end (Russell and O’Brien 2001).

While judicial scholarship has focused on the political factors that increase judicial independence, this scholarship has largely failed to address the role of winning coalitions in these incentive structures (though see Randazzo, Gibler, and Reid 2016). Indeed, most judicial research ignores that ruling elites depend on other groups and must fulfill particular obligations to stay in power. We argue that winning coalitions matter. Winning coalitions seek to shape the legal system to suit their interests (Hirschl 2001), and different winning coalitions have different policy preferences. Failing their winning coalition means that ruling elites are removed from office.

Below, we discuss our theory for two different types of winning coalitions: domestic business elites and foreign business elites. While these are not the only types of winning coalitions, all ruling elites have interests in promoting economic development while demonstrating differences in the extent to which they rely on domestic or foreign sources of capital.

Domestic Business Elite

Winning coalitions composed of domestic business elites can directly affect judicial independence due to the extensive overlap between business and political elites. Political and business elites interchange positions of power, creating a revolving door between politics and business, where business and political elites trade personnel often enough to be considered a single entity (Freitag 1975) and recruitment for positions of government and business are often interchangeable (Oh and Takahara 2018). Indeed, business elites are incentivized to seek political offices to control the government regulations that affect their business (Bunkanwanicha and Wiwattanakantang 2009). Additionally, business elites are increasingly involved in political ventures (Bassett 1996; Peck 1995) and can monopolize advisory bodies (Moore et al. 2002). Economic elites also become a resource for supporting electoral campaigns, providing money, media exposure, network connections, personnel, and infrastructure to candidates and their campaigns—usually in exchange for favorable business policies once in office (Barndt 2014). Ruling elites’ desire to appease their domestic business–winning coalition incentivizes them to make policies and allocate funds in ways that specifically favor the business elites that support them (Bueno de Mesquita et al. 2003).

In both democracies and autocracies, an independent judiciary benefits business elites by protecting property rights and contract rights, even at the potential cost of government judicial constraint (Tag 2021; Ginsburg and Moustafa 2008; Hirschl 2001). Independent court protection of property and contract rights protects business owners and investors by ensuring legal protections of their assets, agreements, and profits. Hence business elites are ensured that they can use their capital to produce goods and services without fear of loss and that these rights will be upheld in court.

We predict that business elite winning coalitions in autocracies will increase judicial independence until some threshold. Business elites benefit from judicial independence only insofar as the courts guarantee legal protections for private property and contract rights. Judicial independence past this point may be detrimental to business elites, such as if the independent courts begin to enforce labor laws, minimum wage, tax laws, environmental regulations, and other aspects that may be costly to business elites. Business elites maximize profit by ensuring the regime retains cheap labor, lax regulations, and minimal taxes and allows business elites to control the banks, natural resources, marketing, and financial institutions (Albertus and Gay 2017). Business elites thus benefit from some degree of judicial independence, but not too much. In other words, judicial independence benefits business elites if it stays functionally a private good (Carrubba 2005). Thus, we expect judicial independence to increase as the ruling elite’s dependence on business elites increases until some midrange point. After this midrange level of judicial independence, we expect judicial independence to decrease so as to reign in courts to protect business elite interests. This leads to our first hypothesis, H1a:

H1a: As dependence on domestic business elites increases, judicial independence will increase in autocracies until some threshold.

We do not expect to see this effect for democracies because democracies are defined by larger and more diverse winning coalitions. Ruling elites in democracies that depend on domestic business elites are also dependent upon nonbusiness elites, including laborers. Because democratic winning coalitions are less exclusive to business elites, judicial independence moves from a private good to a public good. We thus expect the ruling elite’s dependence on domestic business elites in democracies to have no effect on judicial independence because the regime is dependent upon a variety of winning coalitions. This intuition is summarized in our second hypothesis, H1b:

H1b: Increasing dependence on domestic business elites will have no effect on judicial independence in democracies.

Foreign Business Elites

Independent courts also benefit foreign business elites through their protection of private property and contract rights (Tag 2021; Moon 2015; Moustafa 2014; Feld and Voigt 2003). Foreign business elites will only invest in regimes if their investment is protected from the government (Gilson and Milhaupt 2011), where independent courts serve as a credible signal to foreign investors that their business, assets, and property are protected from government appropriation as well as from the regime reneging on initial contracts and policies (Staats and Biglaiser 2011; Moustafa 2008; Jensen 2003; Biglaiser and Staats 2010). This means that judicial independence serves as an indicator to investors that their investments, property, and profits will not be stolen by the government and that the government keeps its promises. Judicial independence thus indicates reduced political risk for investors.

Relatedly, ruling elites seek to attract foreign investment as a potentially immense source of capital gain, with economic advantages so large that ruling elites may be willing to relinquish their control over the judiciary (Pandya 2014). In democracies and autocracies alike, economic growth increases the chance of ruling elites to remain in power (Moon 2015; Feng 1997). Economic growth benefits ruling elites by enriching their winning coalitions and by enabling sufficient resources to help them co-opt or thwart political rivals so as to stay in power (Ginsburg and Moustafa 2008).

Yet foreign business elites as a winning coalition can have different policy preferences compared to domestic business elites.[1] Insofar as foreign investors are investing in industries that require cheap labor and minimal regulations to maintain profits, domestic and foreign business elites may share preferences for judicial independence to increase until a threshold. However, investors may also be investing in industries that require the development of human capital via labor rights, worker safety, access to education, and human rights (Blanton and Blanton 2012)—where foreign investors may pressure the regime for such policies. Similarly, investors from countries with high judicial independence are more likely to invest in countries with judicial independence (Beazer and Blake 2018). Foreign investors may thus pressure a regime to improve judicial independence to replicate the political environment that promoted their economic success in their home country (Ariotti, Dietrich, and Wright 2021). Foreign business elites may also seek to avoid perceptions of their being complicit in repressive politics that could incur market sanctions and reputational costs (Barry, Clay, and Flynn 2013), so they may pressure domestic regimes to adhere to foreign norms and global market standards. Hence the impact of foreign business elites on judicial independence may be less aligned with the ruling elite. This misalignment may cause increases in judicial independence beyond the minimal thresholds required to attract investment. For example, foreign business elites may introduce or enable pressures for economic liberalization that may increase domestic demands for political liberalization and democratization (Gao 2021; Moon 2015; Boix and Stokes 2003). This means that the ruling elite’s dependence on foreign business elites may increase judicial independence beyond what the ruling elite might otherwise prefer and cause a cascade reaction that makes constraining or reducing judicial independence difficult.

Dependence upon foreign business elites can also shift judicial incentives, where judges now have a transnational audience for their decisions (Baum 2006). While domestic business elite dependence maintains domestic audiences for judges, foreign business elite dependence opens judiciaries to foreign audiences and transnational legal communities who can monitor and comment on judicial behavior, introducing rights-based, liberalizing, democratic norms that can influence judges (Risse, Ropp, and Sikkink 1999; Finnemore and Sikkink 1998). Judges may seek to empower the courts, enhance their international reputation, and align themselves with transnational norms (Hirschl 2001)—potentially at the expense of the regime, which finds itself increasingly constrained by an assertive court (Kureshi 2021).

In sum, dependence on foreign business elites introduces foreign and transnational policy norms that may cause policy pressures beyond the control of the regime. We expect that ruling elites will increase judicial independence to attract foreign investment—where this increase in judicial independence occurs when dependence has not yet been established. Ruling elites want to improve judicial independence only up to a threshold, the minimal level of judicial independence that would attract investors. However, while this threshold can be maintained with domestic business elites, this threshold cannot be easily maintained if dependent upon foreign investors because of their preference misalignment. We thus expect judicial independence to continue to increase, particularly in autocracies. Increased dependence on foreign business elites in democracies, however, is not expected to impact judicial independence, since these regimes are the driving forces for transnational global market and democratization norms as well as are beholden to a variety of winning coalitions.[2] These expectations are summarized in our next set of hypotheses, H2a and H2b, below.

H2a: Increased dependence on foreign business elites has no effect on judicial independence in democracies.

H2b: As dependence on foreign business elites increases, judicial independence will increase in autocracies.

Data and Methods

We use the Varieties of Democracy Project (Coppedge et al. 2023) and Quality of Government (Standard) Dataset (Teorell et al. 2023) to compare how different winning coalitions impact judicial independence. Our analyses include 191 countries from 1970 to 2013. We divide our data into three subsets: closed autocracies, electoral autocracies, and democracies.[3] Closed autocracies are countries that do not have multiparty elections for the chief executive or the legislature. These countries are essentially institutionalized, full autocracies (like dictatorships). Electoral autocracies reflect countries that officially have multiparty elections for the chief executive and legislature but do not have free and fair elections in practice. Electoral autocracies thus have features of both autocracies and democracies. Democracies include countries that hold free and fair multiparty elections officially and in practice.

Our dependent variable is judicial independence. This variable measures how often the high court of the country makes decisions that merely reflect government wishes instead of the law or their sincere views of the legal record (Coppedge et al. 2023; Pemstein et al. 2023). Lower values reflect less judicial independence, and higher values reflect more judicial independence.[4]

Our main independent variables are the level of dependence on specific winning coalitions. We capture a regime’s dependence on domestic business elites by a variable that indicates if this winning coalition were to retract their support, then the regime’s chances of losing power would “substantially increase” (Coppedge et al. 2023). Hence for the variable domestic business elites, lower values represent less dependence on business elites, while higher values indicate more dependence.

Because no variable exists that measures foreign business elite dependence, we use proxy measures of foreign direct investment and foreign aid. Foreign direct investment (FDI) is defined as private capital flows that provide a parent firm with at least 10% control over an enterprise outside the home country (Li 2009). We capture foreign direct investment inflow as a percentage of national GDP (Teorell et al. 2023). The FDI variable thus captures the FDI inflow relative to the size of the national economy, thereby indicating the relative importance of FDI to a country’s national economy. We posit that higher levels of FDI reflect a greater dependence of a regime on foreign business elites.

We also capture dependence on foreign business elites via foreign aid as the total amount of foreign aid commitments received by the country (Teorell et al. 2023). Our variable foreign aid reliance represents the total amount of foreign aid money received, where we expect that more money received from foreign aid reflects greater dependence on foreign providers.

We include several control variables, each shown to have an impact on judicial independence. Regime type captures country government differences, where not all democracies are equally democratic, not all autocratic regimes are equally autocratic, and not all hybrid regimes are equally democratic/autocratic. War reflects a national state of emergency, armed conflict, international war, or civil war. National states of emergency and armed conflicts can reduce judicial independence. GDP per capita reflects national economic development, thereby controlling for variation in countries’ economic capacity and development. Regime duration reflects the number of days since the current ruling elite came to power. Ruling elites that have been in power longer have more capacity to effectively govern. Political competition measures how large of the domestic adult population are noteworthy opposition actors to the current ruling elite (Coppedge et al. 2023; Pemstein et al. 2023). These opposition groups may be actively engaging in opposition activities, but this variable also includes those who constitute a dormant threat to the ruling elite. Political fragmentation captures how unified the party control of the national government is, where more division of power across parties can enable judicial independence. Finally, ethnic fractionalization measures the probability that two randomly selected people from a given country will belong to different ethnic or ethnoreligious groups. Increased ethnic fractionalization (i.e., ethnic diversity) can increase competition for resources and political power, thus leading to an increased desire of the ruling elite to stay in power (Randazzo, Gibler, and Reid 2016).

Because we have hypothesized nonlinear threshold relationships, we use fractional polynomial regressions with robust standard errors clustered by country-year. Specifically, we expect judicial independence to increase as domestic business elite dependence increases, until some point where judicial independence stops increasing and begins to decrease. A linear prediction would require that judicial independence always increases as business elite dependence increases. Nonlinearity makes some statistical analyses, like linear regression, unusable because it violates fundamental assumptions of these models. Fortunately, multivariable fractional polynomial regression models allow for nonlinear relationships and for the data to show us where the thresholds are. This allows the data to speak for itself. We cluster standard errors to account for idiosyncratic differences across countries and across time.

Results

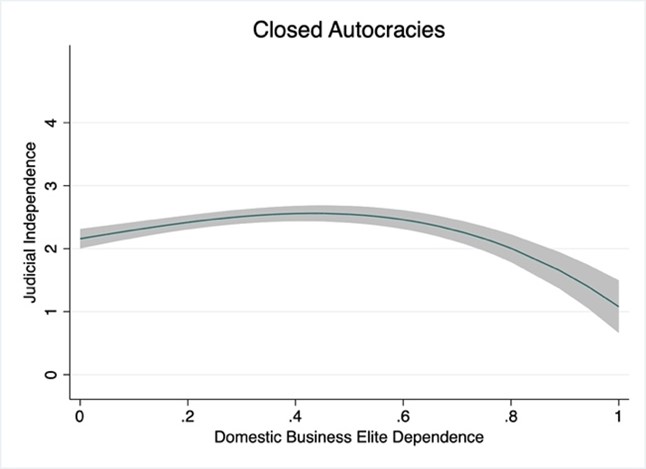

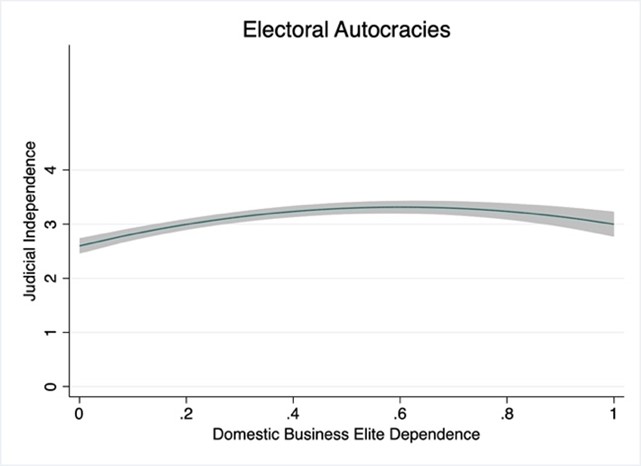

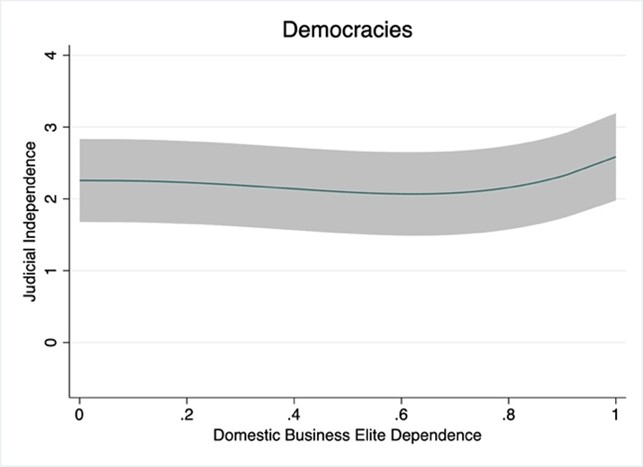

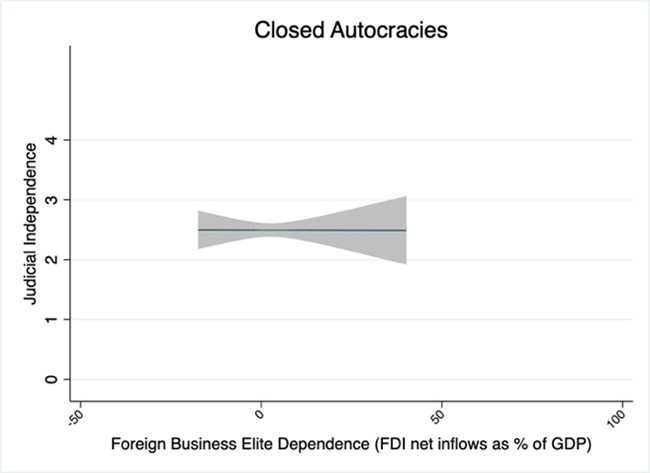

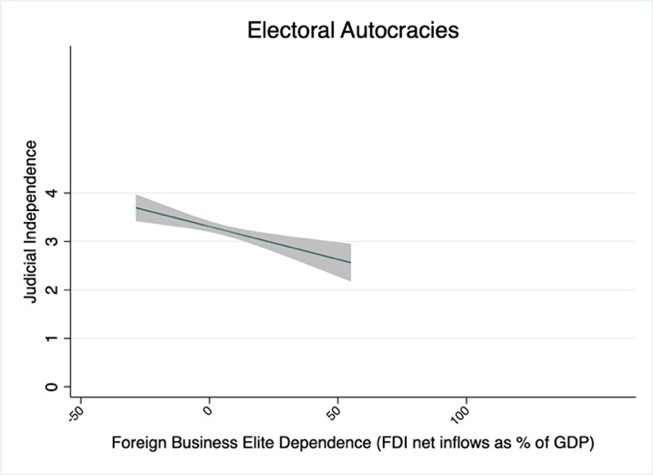

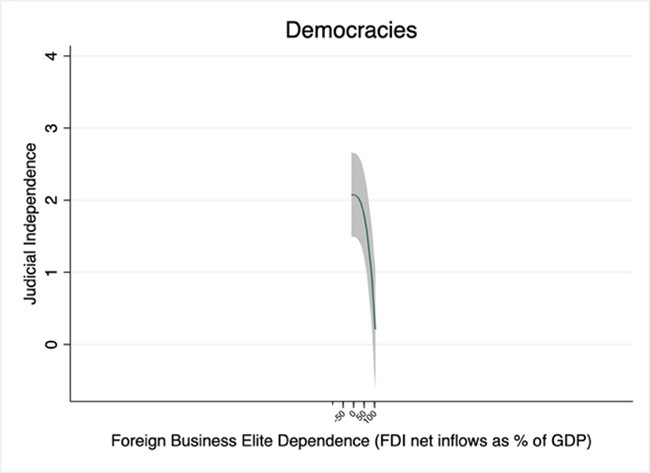

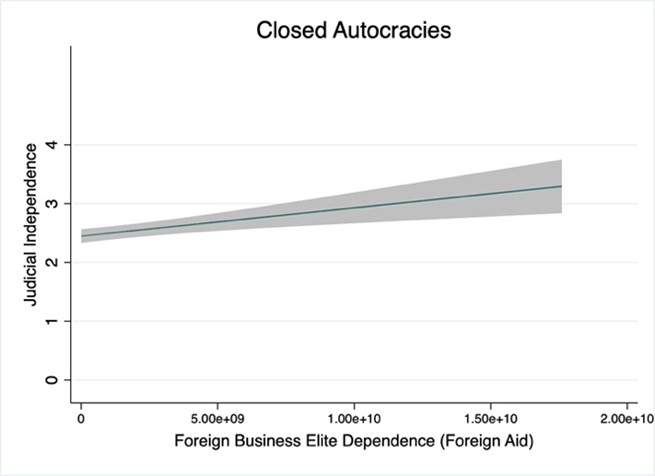

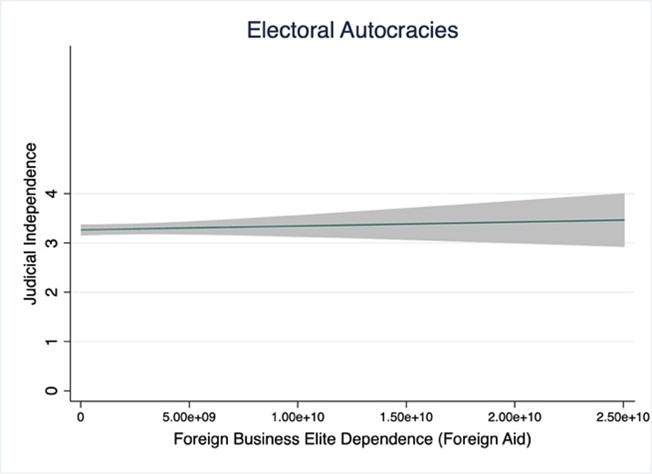

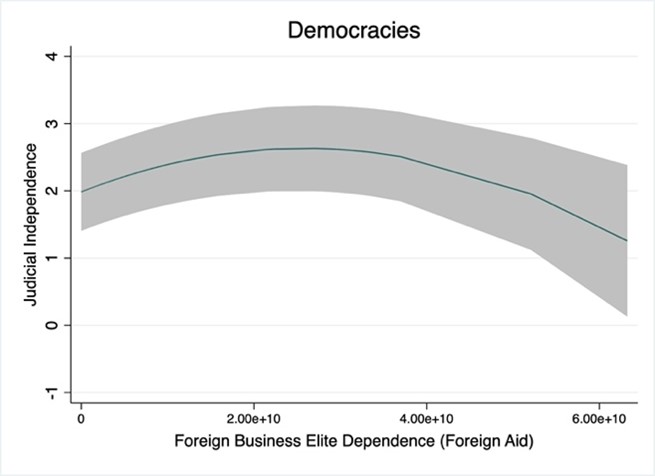

For ease of interpretation, we present the results of our main independent variables in figures 1–3. In each figure, the independent variable (domestic and foreign business elite dependence) is on the x-axis, while our dependent variable (judicial independence) is on the y-axis. The lines in each figure represent the effects of each independent variable on judicial independence. The shaded portions reflect the 95% confidence intervals, illustrating the level of certainty for these effects. Wider shaded margins show that there is more uncertainty about the true effects of each independent variable, while narrower shaded margins represent more certainty about the effects on judicial independence.

For example, figure 1 depicts the effects of a regime’s dependence on domestic business elites on judicial independence. In the left panel, we see the effects of domestic business elite dependence on judicial independence in closed autocracies. The figure has relatively narrow confidence intervals, though these margins increase as dependence increases to the extreme (on the far right of the x-axis). This means we have more uncertainty about the effect of domestic business elite dependence at these higher levels of dependence. The true effect of domestic business elite dependence on judicial independence is somewhere within the shaded margin. The upward-sloping curve shows that dependence on domestic business elites increases judicial independence moderately, at least when the ruling elite begin to depend on them (from 0 to 0.4). Once the ruling elite are sufficiently dependent on them, however, there is a threshold effect (around 0.5)—demonstrated where the curve reaches its peak and begins to slope downward. After this threshold of around 0.5, increased dependence on domestic business elites decreases judicial independence, as reflected in the downward curve. This means that dependence on domestic business elites increases judicial independence until a point where additional dependence reduces judicial independence in closed autocracies. This result supports H1a and uncovers the threshold effect.

In electoral autocracies, depicted in the center panel of figure 1, we see a similar but more moderate effect. As ruling elites begin to depend on domestic business elites, judicial independence increases. Yet a threshold effect appears around the 0.6 mark, where increased dependence no longer increases judicial independence. This result offers support for H1a as well, although there is less of a decline in judicial independence after the threshold compared to that in closed autocracies.

For democracies, in the right panel of figure 1, increased dependence on domestic business elites generally has no effect on judicial independence. The horizontal line and wide confidence margins depict no significant change in judicial independence as dependence increases, supporting H1b.

Figure 2 shows our results regarding ruling elite dependence on foreign business elites, as measured by FDI. We predicted that increased dependence on foreign business elites would have no effect in democracies (H2a) while increasing judicial independence in autocracies (H2b). For closed autocracies, figure 2 illustrates that increased dependence on FDI has no effect on judicial independence. The horizontal line in the left panel shows no changes in judicial independence despite increasing foreign investments. For electoral autocracies, in the center panel, increased dependence on FDI decreases judicial independence, as shown in the downward slope. These results do not support our expectations in H2b. In democracies, increased FDI dependence is associated with a decrease in judicial independence—though most democracies appear to not rely on FDI much (as a proportion of their national economy), as shown by the curve not extending far from 0. These results do not support H2a.

Figure 3 illustrates the effect of ruling elite dependence on foreign business elites, as measured by foreign aid. In closed autocracies, increases in foreign aid are associated with increased judicial independence, as shown in the left panel. This effect is linear, where increased dependence on foreign aid is associated with a continued increase in judicial independence. However, in electoral autocracies (shown in the center panel), increases in foreign aid have no effect on judicial independence. The confidence intervals (shown as shaded margins) become wider as foreign aid increases, indicating more uncertainty, but otherwise, the figure reveals a flat (horizontal) line showing no change in judicial independence regardless of foreign aid. These results offer mixed support for H2b, where our hypothesis is supported for closed autocracies but not for electoral autocracies. In democracies, increases in foreign aid have an unexpected threshold effect. As a democracy receives more foreign aid, judicial independence increases until a threshold (shown in an upward slope until peak), after which more foreign aid decreases judicial independence (shown in a downward slope). These results contradict our expectations in H2a.

Conclusions

In this chapter, we offer the simple theoretical argument that winning coalitions affect judicial independence. We assert that different winning coalitions have different incentives pertaining to judicial independence, where ruling elites who seek to remain in power will promote political and legal systems that benefit their supporting winning coalitions. While this chapter reflects an exploratory analysis with mixed support for our hypotheses, these results reveal an area of research ripe for further inquiry.

We find that different winning coalitions and different levels of dependence upon these winning coalitions have divergent effects. We received support for H1a that domestic business elite reliance on autocracies increases judicial independence until some threshold, as well as support for our expected null effects of domestic business elites in democracies (H1b). We also received support for H2b for closed autocracies, where increased reliance on foreign aid increases judicial independence. Yet several results are counterintuitive and deserve additional investigation. Contrary to our expectations, increased dependence on foreign business elites via foreign direct investment has no effect on judicial independence in closed autocracies and decreases judicial independence in electoral autocracies. Increased dependence on foreign aid in electoral autocracies has no effect on judicial independence, and dependence on foreign business elites appears to be curvilinear, increasing and then decreasing judicial independence in democracies.

One reason for our mixed results is likely due to our overly generalized theoretical approach. Specifically, winning coalitions are not homogenous. Domestic business elites reflect a variety of industries, each with different relationships with law and courts and different relationships with ruling elites. Domestic business elites may thus have different effects based on which industry(s) they represent. For example, domestic business elites that are involved in agriculture may have different effects on judicial independence than business elites in tech industries, mineral export, banking, and so on. Analogously, foreign business elites differ in their policy preferences, including their relationship with ruling elites, political norms from their home countries, types of investments, requirements for investment, and so on (Beazer and Blake 2018). Foreign aid can similarly differ in the requirements for a country to receive or be eligible for foreign aid (such as requiring judicial reforms), donor type (country or international organization), donor selection priorities and funding opportunities, and number of donors. Each of these aspects may determine the effect foreign aid has on judicial independence. Future research should, therefore, consider addressing the effects of individual winning coalitions or subgroups as well as investigating the foreign aid donor-recipient relationships.

Future research would also benefit from exploring how ruling elites and their winning coalitions engage in negotiation to generate mutual contractual or implicit relationships. Ruling elites may offer benefits other than judicial independence to satisfy their winning coalitions. Considering these evolving relationships, dialogue, and negotiations to better understand which coalitions may impact judicial independence and under what conditions would benefit this area of inquiry. Despite these limitations, this exploratory analysis offers promising avenues for future research.

Learning Activity

Theory Building

- What are the different business industries in your country? Write a list of all the industries you can think of.

- How do law and politics influence each of these industries? How might politics impact their profit, production, labor, wages, resources, taxes, transparency, technological and research development, consumer protections, marketing, trade, investment, contracts, private property, copyright, and partnerships?

- How might each of these industries try to build relationships with the political elite (such as executive, legislature, or political parties)? How can political and legal systems assist each business industry in its profit and success? How would these relationships differ across democratic regimes compared to autocratic regimes?

- What kinds of laws would help or hinder each business industry? Which of these laws might appear before a court?

- How might an independent court rule on these laws compared to a dependent court? How might regime type influence an independent court’s decisions versus a dependent court’s decisions on these laws?

- Does the United States Supreme Court favor business or business elites? Do financial resources influence Supreme Court decisions, and if so, how?

References

Albertus, Michael, and Victor Gay. 2017. “Unlikely Democrats: Economic Elite Uncertainty under Dictatorship and Support for Democratization.” American Journal of Political Science 61 (3): 624–41.

Ariotti, Margaret, Simone Dietrich, and Joseph Wright. 2022. “Foreign Aid and Judicial Autonomy.” Review of International Organizations 17 (4): 691–715.

Aydin, Aylin. 2013. “Judicial Independence across Democratic Regimes: Understanding the Varying Impact of Political Competition: Judicial Independence across Democratic Regimes.” Law & Society Review 47 (1): 105–34.

Barndt, William T. 2014. “Corporation-Based Parties: The Present and Future of Business Politics in Latin America.” Latin American Politics and Society 56 (3): 1–22.

Barry, Colin M., K. Chad Clay, and Michael E. Flynn. 2013. “Avoiding the Spotlight: Human Rights Shaming and Foreign Direct Investment.” International Studies Quarterly 57 (3): 532–44.

Bassett, Keith. 1996. “Partnerships, Business Elites and Urban Politics: New Forms of Governance in an English City?” Urban Studies 33 (3): 539–55.

Baum, Lawrence. 2006. Judges and Their Audiences. Princeton University Press.

Beazer, Quintin H., and Daniel J. Blake. 2018. “The Conditional Nature of Political Risk: How Home Institutions Influence the Location of Foreign Direct Investment.” American Journal of Political Science 62 (2): 470–85.

Biglaiser, Glen, and Joseph L. Staats. 2010. “Do Political Institutions Affect Foreign Direct Investment? A Survey of US Corporations in Latin America.” Political Research Quarterly 63 (3): 508–22.

Blanton, Robert G., and Shannon L. Blanton. 2012. “Rights, Institutions, and Foreign Direct Investment: An Empirical Assessment.” Foreign Policy Analysis 8 (4): 431–51.

Boix, Carles, and Susan C. Stokes. 2003. “Endogenous Democratization.” World Politics 55 (4): 517–49.

Bueno de Mesquita, Bruce, Alastair Smith, Randolph M. Siverson, and James D. Morrow. 2003. The Logic of Political Survival. MIT Press.

Bunkanwanicha, Pramuan, and Yupana Wiwattanakantang. 2008. “Big Business Owners in Politics.” Review of Financial Studies 22 (6): 2133–68.

Carrubba, Clifford. 2005. “Courts and Compliance in International Regulatory Regimes.” The Journal of Politics 67: 669–89.

Clark, Tom S. 2006. “Judicial Decision Making during Wartime.” Journal of Empirical Legal Studies 3: 397–419.

Collins, Paul M., Jr., Daniel A. Norton, Kenneth L. Manning, and Robert A. Carp. 2008. “International Conflicts and Decision Making on the Federal District Courts.” Justice System Journal 29: 121–44.

Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Staffan I. Lindberg, Jan Teorell, David Altman, Michael Bernhard, et al. 2023. “V-Dem [Country-Year/Country-Date] Dataset v13.” Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project. https://doi.org/10.23696/vdemds23.

Epstein, Lee, Daniel E. Ho, Gary King, and Jeffrey A. Segal. 2005. “The Supreme Court during Crisis: How War Affects Only Non-war Cases.” New York University Law Review 80 (1): 1–116.

Feld, Lars P., and Stefan Voigt. 2003. “Economic Growth and Judicial Independence: Cross-Country Evidence Using a New Set of Indicators.” European Journal of Political Economy 19 (3): 497–527.

Feng, Yi. 1997. “Democracy, Political Stability and Economic Growth.” British Journal of Political Science 27 (3): 391–418.

Finkel, Jodi S. 2008. Judicial Reform as Political Insurance: Argentina, Peru, and Mexico in the 1990s. University of Notre Dame Press.

Finnemore, Martha, and Kathryn Sikkink. 1998. “International Norm Dynamics and Political Change.” International Organization 52: 887–919.

Freitag, Peter J. 1975. “The Cabinet and Big Business: A Study of Interlocks.” Social Problems 23 (2): 137–52.

Gao, Jacque. 2021. “Democratization in the Shadow of Globalization.” International Organization 75 (3): 698–734.

Gibler, Douglas M., and Kirk A. Randazzo. 2011. “Testing the Effects of Independent Judiciaries on the Likelihood of Democratic Backsliding.” American Journal of Political Science 55: 696–709.

Gilson, Ronald J., and Curtis J. Milhaupt. 2011. “Economically Benevolent Dictators: Lessons for Developing Democracies.” American Journal of Comparative Law 59 (1): 227–88.

Ginsburg, Tom, and Tamir Moustafa, eds. 2008. Rule by Law: The Politics of Courts in Authoritarian Regimes. Cambridge University Press.

Helmke, Gretchen, and Frances Rosenbluth. 2009. “Regimes and the Rule of Law: Judicial Independence in Comparative Perspective.” Annual Review of Political Science 12: 345–66.

Henisz, Witold. 2000. “The Institutional Environment for Multinational Investment.” Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization 16 (2): 334–64.

Hirschl, Ran. 2001. “The Political Origins of Judicial Empowerment through Constitutionalization: Lessons from Israel’s Constitutional Revolution.” Comparative Politics 33 (3): 315–35.

Howard, Robert M., and Henry F. Carey. 2004. “Is an Independent Judiciary Necessary for Democracy?” Judicature 87 (6): 284–90.

Jensen, Nathan M. 2003. “Democratic Governance and Multinational Corporations: Political Regimes and Inflows of Foreign Direct Investment.” International Organization 57: 587–616.

Kureshi, Yasser. 2021. “When Judges Defy Dictators.” Comparative Politics 53 (2): 233–55.

Li, Quan. 2009. “Outlier, Measurement, and the Democracy-FDI Controversy.” Quarterly Journal of Political Science 4 (2): 167–81.

Linzer, Drew, and Jeffrey Staton. 2015. “A Global Measure of Judicial Independence, 1948–2012.” Journal of Law and Courts 3 (2): 223–56.

Moon, Chungshik. 2015. “Foreign Direct Investment, Commitment Institutions, and Time Horizon: How Some Autocrats Do Better Than Others.” International Studies Quarterly 59 (2): 344–56.

Moore, G., S. Sobieraj, J. A. Whitt, O. Mayorova, and D. Beaulieu. 2002. “Elite Interlocks in Three U.S. Sectors: Nonprofit, Corporate, and Government.” Social Science Quarterly 83 (3): 726–44.

Moustafa, Tamir. 2008. “Law and Resistance in Authoritarian States: The Judicialization of Politics in Egypt.” In Rule by Law: The Politics of Courts in Authoritarian Regimes, edited by Tom Ginsburg and Tamir Moustafa, 132–55. Cambridge University Press.

Moustafa, Tamir. 2014. “Law and Courts in Authoritarian Regimes.” Annual Review of Law and Social Science 10 (1): 281–99.

Oh, Ingyu, and Takahara Taichi. 2018. “From Business to Politics: Cross-Border CEOs and Political Leadership in Japan and South Korea.” Asia Pacific Business Review 25 (2): 173–93.

Pandya, Sona. S. 2014. “Democratization and Foreign Direct Investment Liberalization, 1970–2000.” International Studies Quarterly 58 (3): 475–88.

Peck, Jamie. 1995. “Moving and Shaking: Business Élites, State Localism and Urban Privatism.” Progress in Human Geography 19 (1): 16–46.

Pemstein, Daniel, Kyle L. Marquardt, Eitan Tzelgov, Yi-ting Wang, Juraj Medzihorsky, Joshua Krusell, Farhad Miri, and Johannes von R ̈omer. 2023. “The V-Dem Measurement Model: Latent Variable Analysis for Cross-National and Cross-Temporal Expert-Coded Data.” V-Dem Working Paper No. 21. 8th ed. University of Gothenburg, Varieties of Democracy Institute.

Popova, Maria. 2010. “Political Competition as an Obstacle to Judicial Independence: Evidence from Russia and Ukraine.” Comparative Political Studies 43 (10): 1202–29.

Ramseyer, J. Mark. 1994. “The Puzzling (in) Dependence of Courts: A Comparative Approach.” Journal of Legal Studies 23: 721–47.

Randazzo, Kirk, Douglas Gibier, and Rebecca A. Reid. 2016. “Examining the Development of Judicial Independence.” Political Research Quarterly 69 (3): 583–93.

Risse, Thomas, Stephen C. Ropp, and Kathryn Sikkink. 1999. The Power of Human Rights: International Norms and Domestic Change. Cambridge University Press.

Russell, Peter H., and David M. O’Brien, eds. 2001. Judicial Independence in the Age of Democracy: Critical Perspectives from Around the World. University Press of Virginia.

Shapiro, Martin. 1981. Courts, a Comparative and Political Analysis. University of Chicago Press.

Sievert, Jacqueline M. 2018. “The Case for Courts: Resolving Information Problems in Authoritarian Regimes.” Journal of Peace Research 55 (6): 774–86.

Staats, Joseph L., and Glen Biglaiser. 2011. “The Effects of Judicial Strength and Rule of Law on Portfolio Investment in the Developing World.” Social Science Quarterly 92 (3): 609–30.

Tag, Mehmet Nasih. 2021. “Judicial institutions of Property Rights Protection and Foreign Direct Investment Inflows.” International Review of Law and Economics 65: 105975.

Tate, C. Neal, and Torbjorn Vallinder. 1995. The Global Expansion of Judicial Power. New York University Press.

Teorell, Jan, Aksel Sundström, Sören Holmberg, Bo Rothstein, Natalia Alvarado Pachon, Cem Mert Dalli, and Yente Meijers. 2023. The Quality of Government Standard Dataset, Version Jan 23. University of Gothenburg, Quality of Government Institute. https://www.gu.se/en/quality-government doi:10.18157/qogstdjan23.

Vanberg, Georg. 2015. “Constitutional Courts in Comparative Perspective: A Theoretical Assessment.” Annual Review of Political Science 18: 167–85.

- Incorporating foreign business may also create tensions with the domestic business elite, where there is increased competition in a regime’s market where it was once monopolized by the domestic elite (Gao 2021). ↵

- While autocratic foreign business elites may invest in democracies, they usually are forced to adapt to the more constrained political and economic environment of the democracy. Hence the autocratic norms introduced by these elites are not likely to systematically impact the host democratic regime. ↵

- Subsetting the data by regime type allows us to see how each of our independent variables impacts judicial independence across regimes. ↵

- Because causal arguments require that causes occur before their effect, all our independent variables (i.e., causes) are measured a year before our dependent variable (judicial independence). This way we can test whether changes in causes are followed by changes in judicial independence. For example, to evaluate whether our independent variables systematically change judicial independence, we are seeing if the independent variables in 1980 caused a change in judicial independence observed in 1981. ↵