Actors in the Judicial Process

7 Trump’s Judges and Diversity

Regression to the Mean or Remaking the Judiciary?

Petar Jeknic; Rorie Spill Solberg; Eric Waltenburg; and Christopher Stout

At the beginning of the Trump presidency, there was a great deal of commentary and handwringing focused on how unusual this president was and would be.[1] Norm-breaking became the watchword, as President Trump ignored the typical or standard patterns of presidential behavior. Examples of shattered norms include President Trump’s refusal to release his income taxes, his denigration of military service, and his willingness to side with foreign adversaries over the conclusions of his own intelligence community.[2] Now norms have developed over time in the realm of judicial nominations as well. Presidents since Clinton had been increasing the diversity of their judicial slates regardless of party. While some presidents certainly focused strongly on ideology, diversity was also a major component of their judicial selection strategy (Solberg and Diascro 2018, 2009; Solberg 2005; Spill and Bratton 2001). Based on President Trump’s comments and his Supreme Court short list, it was hypothesized that the ideology of his nominees would be a touchstone for his selection process—a hypothesis confirmed when Leonard Leo, cochairman of the Federalist Society, took a central role in the judicial selection process for the administration. Early in the Trump presidency, though, it also seemed clear that he would not take the same two-pronged approach as did his more recent predecessors and also consider diversity. Indeed, he looked to be the first president in over two decades that would reduce the diversity of the federal bench.[3] With the conclusion of the Trump presidency, it is time to take stock and investigate the effects of Trump’s cohort of judges on the demographics of the federal judiciary.

As several other articles in this volume attest, assessing the diversity of a political institution, particularly the judiciary, is an important exercise. The judiciary, be it federal or state, in the US system is an odd duck. The system is set up for the judiciary to act as umpire over conflicts between the government and its citizens, between citizens, and between institutions of government. (For example, the Supreme Court determined that Congress did not have the power to subpoena President Trump’s tax returns as part of its oversight and legislative power in Trump et al. v. Mazars USA, LLP No. 19-715.) Yet the judiciary is generally selected via appointment (federal system and some states) or via merit selection (appointment combined with retention elections). Even in systems where judges are elected directly, the elections tend to be low-information and low-participation events (Klein and Baum 2001). Therefore, judges and justices have little to no direct connection to the electorate and generally serve no constituency.[4] Compounding this indirect link to the public is the lack of enforcement power inherent in the structure of US courts. Judges and justices can make decisions; however, in a separation of powers government, it is up to the executive branch to enforce or implement those decisions. Thus as Hamilton so aptly put it over two hundred years ago, the judiciary has “no influence over either the sword or the purse.…It may truly be said to have neither Force nor Will, but merely judgment.” To remain consequential and relevant in such a system, then, the judiciary must remain legitimate in the eyes of the public so that those with the power of purse and sword feel compelled to enact and abide by the judiciary’s ruling. In other words, the judiciary must maintain trust and approval to fulfill its critical role in our system.

While there may be many reasons the public supports and approves of the federal judiciary (and approves more heartily of the judiciary than other national institutions), research shows that one important component of this approval is diversity. We trust institutions that mirror society. Women and people of color are more likely to support and legitimate institutions where they feel welcome. They also tend to believe that the institution is fairer when the panoply of decision-makers is diverse (Ulbig 2007). It is not about whether women or people of color make decisions differently than white and male judges; it is not a question of substantive diversity. It is the result of symbolic diversity. The mere presence of a diverse bench yields tangible benefits for an institution that relies solely on its legitimacy for its power. For example, Lee et al. (2021) show that women viewing a woman in the role of Chief Justice of a state Supreme Court have greater overall support for the court as an institution. This finding follows a long literature that shows that a reasonable representation of the demographic characteristics of the general population is required for fair outcomes (Easton 1965; Pitkin 1967; Mansbridge 1999; Gay 2002).[5]

Besides the boon for legitimating the judiciary and its use of its power, a diverse judiciary is also important for substantive representation as well. First, studies of diversity writ large show that more diverse groups make better decisions (see, for example, Herring 2009). More varied points and possible solutions are considered when groups are heterogeneous rather than homogeneous. And while the studies are mixed, it does seem that the lived experiences of women and judges of color can lead to different decisions. Even if the decision or the final outcome does not change, the shape of the policy and the consideration of the issues can be affected by the diversity of the group (see the excellent review in Boyd et al. 2010). The effect might be more obvious at the appellate courts where judges make decisions in small groups (three, nine, or en banc); however, research shows that there are also similar effects at the trial courts. Although each judge decides cases on his or her own, the presence of diverse colleagues still creates the same effects. The benefits of diversity are compounded as judges work to diversify their staffs, especially the clerks they hire (Mauro 2014; Benson 2007).

Given the benefits of diversity for the institution as a whole and for its overall legitimacy, assessing the diversity of each president’s judicial nominees is a worthy scholarly endeavor. While the early narratives on the Trump presidency suggested that his administration’s laser focus on ideology would yield a judiciary that appreciably reverses the steps taken toward a more diverse federal judiciary, this is, in fact, an assumption that can be put to empirical tests. Accordingly, we examine Trump’s federal judges overall and then separately at the district and appellate level to see if and how the demographics of the bench have changed over the course of Trump’s tenure.

Trump’s Judicial Cohort

The federal judiciary is staffed by a multitude of judges—Article III judges, bankruptcy judges, and magistrates. In this study, we focus on Article III judges—judges appointed for life tenure by the president to seats created under Congress’s Article III power to create inferior courts. There are two types of Article III judges—active judges and senior status judges. Active judges are full-time Article III judges. Senior status judges are judges who have reached at least the age of sixty-five and have served the number of years on the bench that, when added to their age, equals eighty. These judges serve in a reduced capacity, depending on their court; their “active” seat is considered open and available for replacement. Thus senior status judges serve alongside the active judiciary.[6]

When examining any presidential judicial legacy in terms of diversity, we argue that one must consider the entire judiciary, including the senior status judges, and you must examine the entire federal structure both as a whole and by its constituent parts. In other words, just examining the judicial cohort of any president does not provide a good lens for understanding the diversity of the full domain of the federal judiciary. Additionally, the judiciary is more than the sum of its parts. If there are some courts that are highly diverse and others that remain homogeneous, then the judiciary as a whole may not reap the benefits of diversity. Therefore, we examine President Trump’s judicial cohort overall, in comparison to the entire judiciary, and then look at how his nominees have affected the demographic profile of the district and appellate courts as a whole and on individual courts. This broader view provides a complete picture of the demographic impact of Trump’s judges.

The Overall Picture

President Trump’s judicial cohort is 85 percent white and 76 percent male. This is a modest improvement from earlier in his presidency in terms of racial diversity. Solberg and Waltenburg (2018) report that after the first seventeen months of the Trump presidency his judicial cohort was 75 percent male and 90 percent white. About three-quarters of his nominees (72 percent) filled seats on the district courts, and 27 percent filled appellate vacancies.

In terms of overall nominations, President Trump easily outpaced President Obama, confirming a total of 200 judges by July 2020[7] compared to President Obama’s 153. This comparison, however, may not be fully appropriate inasmuch as President Obama was considered to be slow off the mark in terms of judicial nominations.[8] Additionally, Obama faced a recalcitrant Senate majority for the second half of his first term, whereas Trump had a significant ally on judicial nominations in Leader McConnell (R-KY). If we compare President Trump’s first term to the first terms of G. W. Bush, Clinton, or even G. H. W. Bush, we see that his overall confirmation rate is still higher than that of his predecessors (169, 182, and 193 respectively).[9] In other words, President Trump’s administration clearly prioritized judicial confirmations and was highly successful in making them. We now turn to examine how Trump’s judicial nominations have altered (if they altered) the demographic profile of the lower federal courts. We begin with the courts of appeals and then turn to the more numerous district courts.

Courts of Appeals

President Trump clearly had a plan when it came to the judiciary. The plan went beyond “appoint conservative judges.” His administration recognized the substantial power that sits at the federal courts of appeals. These appellate courts, the middle tier of the federal judiciary, make an incredible amount of law and hear thousands of cases per year compared to the paltry seventy-five the US Supreme Court hears in the current era. Thus the Trump administration focused a great deal on the appellate courts and appointed more appellate judges in the first two years than most other presidents (see Solberg and Waltenburg 2018a, b, and c). By the end of his term, the courts of appeals were fully staffed and there were no vacancies.[10]

Also, by the end of the Trump presidency, the complexion of the US courts of appeals was paler and there was more testosterone—in other words, the courts were whiter and more male. The direction of this change bucks the trend established during the Clinton administration of increasing diversity. Since Clinton, each president, regardless of party, has increased the diversity on the judiciary as a whole and on the courts of appeals. While President Trump’s appointments have not contributed to this trend, the effect of his appointments overall is not particularly extreme. As table 1 shows, when you include active and senior status judges, the change in terms of gender is barely perceptible. Once Trump’s extremely homogenous pool of nominees is added to the larger pool, their impact was diluted.[11] The percentage of seats held by white judges only increased by about 1 percent. This increase came mostly at the expense of African American and Latinx representation. President Trump increased the share of seats held by Asian Americans, continuing an outreach to this community that began under President Obama (Solberg and Diascro 2020). Though the overall numbers are still small, Trump nearly tripled the number of Asian American judges on the Courts of Appeal.

| Demographic | Active Judges (n=179) | Senior Status Judges (n=117) | Total Judges (n=296) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 118 (65.9) | 101 (86.3) | 219 (74.0) |

| Female | 61 (34.1) | 16 (13.7) | 77 (26.0) |

| White | 138 (77.1) | 108 (92.3) | 246 (83.1) |

| African American | 17 (9.5) | 4 (3.4) | 21 (7.1) |

| Hispanic | 13 (7.3) | 4 (3.4) | 17 (5.7) |

| Asian American | 11 (6.2) | 1 (0.9) | 12 (4.1) |

| Pacific Islander | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Native American | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mixed race | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Larger differences, though, are clear when you compare President Obama’s and President Trump’s judicial cohorts rather than examining the overall impact on the courts of appeals. President Obama’s judicial nominees were extremely diverse by most standards (Solberg and Diascro 2020). Although George W. Bush also pursued diversity as a goal for his judicial nominees and succeeded to a great extent (see Diascro and Solberg 2009), as table 2 reveals, his efforts paled in comparison to President Obama’s. When we compare the Trump and Obama cohorts side by side, we see that President Trump’s cohort for the appellate courts was far less diverse than Obama’s. Indeed, President Trump’s appellate judges are actually less diverse than President G. W. Bush’s. In fact, President Trump nominated more white judges to the federal appellate bench than his past three predecessors; he almost matches President Carter in the percentage of white judges appointed to the intermediate appellate courts some four decades earlier.[12]

| Demographic | Total | Percentage | Percent change from Obama to Trump |

Percent change from G.W. Bush to Obama* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 42 | 79.2 | +20.3 | -18.2 |

| Female | 11 | 20.8 | -20.2 | +18.2 |

| White | 45 | 84.9 | -20.2 | -19.2 |

| African American/mixed | 0 | 0 | -19.8 | +6.2 |

| Hispanic/mixed | 1 | 1.8 | -9.3 | +5.8 |

| Asian American/Pacific Islander/mixed | 7 | 13.2 | +6.5 | +7.3 |

* Data for the George W. Bush administration comes from Goldman et al. (2008)

The effect of Trump’s nominees on the diversity of the courts of appeals is made clearer by table 3. By the end of the Obama presidency, there were no all-white appellate courts. All but one appellate court held some descriptive representation for Black Americans. The number of courts with no representation for Latinx or Asian Americans was also greatly reduced (from seven to four and thirteen to nine respectively). Women of color were more present across these courts after the Obama presidency. At the end of the G. W. Bush administration, eight of the thirteen courts had no intersectional representation, and this was further reduced over Obama’s presidency to six courts. President Trump’s replacement strategy, which seems to almost wholly ignore diversity as a goal, saw an uptick in the number of appellate courts without an African American or Hispanic American sitting on the bench. Currently, two of the thirteen courts seat no Black judges and five seat no Latinx judges. Additionally, the number of appellate courts without a woman of color present increased from six to seven. This is mainly because President Trump replaced four Black women but only appointed two women of color to the appellate courts (one Latina and one Asian American). The only demographic that seems to have benefited from President Trump’s nominations besides white people, at least in terms of demographic representation, are Asian Americans. President Trump nominated more Asian Americans to the courts of appeals than any of his predecessors and reduced the number of appellate courts without Asian American representation from nine to seven. While President Obama also used judicial appointments to engage this emerging voting block (see Solberg and Diascro 2020), it is clear that President Trump is doing so more boldly, given his general lack of concern regarding the racial diversity of his appointments.

| All male | All white | No African Americans | No Hispanics | No Asian Americans | No women of color | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 0 | 0 | 1 (7%) | 4 (31%) | 9 (69%) | 6 (46%) |

| 2020 | 0 | 1 (7%) | 2 (15%) | 5 (38%) | 7 (53%) | 7 (53%) |

Investigations of other presidents’ nominations revealed clear and consistent patterns. Carter used new seats provided by the Omnibus Judges Act of 1978 to diversify the courts.[13] Clinton followed a different strategy in which he generally replaced women with women and judges of color with other judges of color (see Spill and Bratton 2001). For President Trump, the replacement strategy is fairly straightforward: in most instances, the replacement will be white and male. Again, the only exception is for Asian Americans, where no members of this demographic left the bench and seven were appointed (13.2 percent of Trump’s appellate nominees). Most of these judges replaced white judges (N = 6). Only one replaced another judge of color (Latinx).

As the above tables also attest, overall the circuit courts have become more male under President Trump, again reversing trends from the last three presidents. Almost 44 percent of President Obama’s circuit court judges were women. For President Trump, the percentage drops significantly to almost 21 percent; however, women remain represented on all appellate courts despite the low numbers of appointments in the last four years.[14]

In general, Trump’s nominations to the courts of appeals have not altered the demographic complexion of the intermediate federal courts as much as many forecasted. However, the continued levels of diversity have less to do with Trump taking diversity into account and more to do with the focus on diversity that held sway for presidents Clinton, G. W. Bush, and Obama. Their joint efforts to diversify the bench have blunted the impact of an appellate cohort that is 79 percent male and almost 85 percent white.[15]

District Courts

As we turned our attention to the US district courts, the trial courts of the federal system, we anticipated that Trump’s nominees would be more diverse than those we see at the courts of appeals simply because the district courts are so much more numerous and vacancies are more frequent. To put it more concretely, there are so many opportunities to appoint a judge to the federal trial courts that the law of large numbers assures that some of these picks, in the modern era, will be women and/or judges of color. Additionally, the literature also suggests that it is easier to diversify less prestigious institutions, and while any federal judicial seat is a plum position, the district courts are considered less prestigious than the appellate bench (Diamond 1977; Squire 1992).[16] Even for presidents less concerned with diversity, the district courts tend to offer enough opportunities for appointments that we expect to see greater diversity regardless, and indeed this is the case.

Table 4 provides overall demographic data on all 94 district courts. As you can see, these courts are slightly less male and white than the courts of appeals; however, when we consider only active judges, the differences are negligible (66.8 percent male versus 65.9 percent) for gender, and a bit broader for race, with 72 percent of the district court judges self-identifying as white and 77 percent of the appellate bench similarly self-identifying. Again, given the overall size of the district courts in comparison to the courts of appeals (677 versus 179, respectively) and the findings in the literature, we would expect more diversity in the district courts than the appellate courts. However, the federal courts as an institution do not reveal that expected pattern. We can only speculate as to why this is the case and suspect that while the federal district courts are less prestigious when compared to the federal appellate courts, this difference is not significant enough to generate the gender divide seen in other institutions. Simply put, federal trial court judgeships are sufficiently prestigious to see a skew toward white men on these courts. Additionally, while the overall number of judgeships here is much higher (4.5x), these courts are distributed across the nation and many of them are actually quite small. So while the district courts are a “larger” institution, the geographic distribution and separation of the individual courts might mitigate the pattern found previously in the literature.

| Demographic | Active judges (n=605) | Senior status judges (n=460) |

Total judges (n=1065) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 404 (66.8) | 366 (79.6) | 770 (72.3) |

| Female | 201 (33.2) | 94 (20.4) | 295 (27.7) |

| White | 437 (72.2) | 407 (88.5) | 844 (79.2) |

| African American | 81 (13.4) | 32 (7.0) | 113 (10.6) |

| Hispanic | 55 (9.1) | 17 (3.7) | 72 (6.8) |

| Asian American/Pacific Islander | 22 (3.6) | 3 (0.7) | 25 (2.4) |

| Native American | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.2) |

| Mixed Race | 9 (1.5) | 0 | 9 (0.8) |

While the overall picture of the district courts is interesting, our focus here is on Trump’s judicial nominees, and so we now turn to examine his trial bench cohort. Again, the difference between President Trump’s judicial cohort and President Obama’s is quite glaring. However, we caution that President Obama’s appointment behavior was a large departure from his predecessors, and President Trump’s trial court nominees are more like G. W. Bush’s cohort (See table 5). For example, President Trump’s trial court judges are a smidge over 15 percent more male than Obama’s; whereas Obama’s were 20 percent more female than President G. W. Bush’s district court judges. In terms of race and ethnicity, though, President Trump’s cohort is distinctly white, much more so than President Obama’s and even President G. W. Bush’s. And while President Trump can be lauded for continuing to increase representation of Asian Americans, this increase comes at the expense of other underrepresented groups on the bench, particularly Black and Latinx judges. Clearly, President Trump is not continuing G. W. Bush’s use of judicial nominations as a tool for outreach to the Latinx community, at least not in the lower federal courts.

| Demographic | Number of nominees (n=143) | Percentage | Percent change from Obama to Trump | Percent change from G.W. Bush to Obama* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 106 | 74.1 | +15.1 | -20.3 |

| Female | 37 | 25.9 | -15.1 | +20.3 |

| White | 122 | 85.3 | +20.4 | -16.2 |

| African American/mixed | 9** | 6.3 | -13.5 | +12.9 |

| Hispanic/mixed | 7 | 4.9 | -6.2 | +.8 |

| Asian American/Pacific Islander/mixed | 5 | 3.5 | +3.2 | +5.2 |

| Native American/mixed | 1 | 0.7 | +0.4 | +.3 |

* Data for the George W. Bush administration comes from Goldman et al. (2007).

** Ada E. Brown (N.D. Tex.) is Black/Native American and is included in both categories. As a result, the percentages add up to 100.7 percent because one appointee is counted twice.

This picture of Trump’s demographic impact is clearer when we examine the diversity across the district courts by demographic category. Table 6 shows that President Trump’s lack of diversity in his cohort is increasing the number of courts lacking key demographics. Even though President Trump seems to be reaching out to the Asian American community more than previous presidents, these nominees have not been distributed in a way that actually increases the number of courts with this representation. Indeed, the number of district courts without Asian American representation increased from seventy-three to seventy-six during Trump’s term, highlighting plainly how underrepresented this group is among federal judges. Similarly, under President Trump the number of courts without any judges of color or women increased as did the number of courts without women of color, and without Black or Latinx representation.

| All white and all male | All male | All white | No African Americans | No Hispanics | No Asian Americans | No women of color | No white people | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 6

(6%) |

8

(9%) |

36

(38%) |

42

(45%) |

64

(68%) |

73

(78%) |

52

(55%) |

1

(1%) |

| 2020 | 7

(7%) |

9

(10%) |

37

(39%) |

43

(46%) |

67

(71%) |

76

(81%) |

55

(59%) |

2

(2%) |

When we consider the sheer number of appointments made to the federal courts, the only pattern that really emerges is that President Trump worked fairly hard to create a homogenous cohort that is significantly male and white. Again, table 6 provides the overall impact of Trump’s appointments on several diversity categories. The next four tables (7 through 10) provide a different perspective on diversity by keying in on the replacement effects of the Trump judges on district and appellate courts. These tables reveal that for men, white people, and Asian Americans the numbers of appointed are higher than the numbers replaced. This pattern holds for all three of these groups, but the overall numbers of Asian Americans in this category (five appointed and two replaced) are extremely small in comparison to the other two groups (white and male)—highlighting the very clear pattern of homogeneity in the Trump nominating class.

| Race/ethnicity | Total appointed | Total replaced | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| White | 122

85.3% |

125

87.4% |

-3 |

| African American | 7

4.9% |

11

7.7% |

-4 |

| Latino/a | 7

4.9% |

5

3.5% |

+2 |

| Asian American/Pacific Islander | 5

3.5% |

2

1.4% |

+3 |

| Mixed race | 2

1.4% |

0 | +2 |

| Gender | Total appointed | Total Replaced | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 106

74.1% |

100

69.9% |

+6 |

| Female | 37

25.9% |

43

30.1% |

-6 |

| Race/ethnicity | Total appointed | Total replaced | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| White | 45

84.9% |

45

84.9% |

0 |

| African American | 0 | 4

7.5% |

-4 |

| Latino/a | 1

1.9% |

4

7.5% |

-3 |

| Asian American | 7

13.2% |

0 | +7 |

| Gender | Total appointed | Total replaced | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 42

79.2% |

40

75.5% |

+2 |

| Female | 11

20.8% |

13

24.5% |

-2 |

Yet again, these numbers look particularly bad when compared to the numbers from the Obama administration. However, this dyadic comparison may be unfair, as it is possible that Obama was the outlier rather than Trump (see Solberg and Diascro 2020). To place President Trump’s judges in a historical context, we compare President Trump’s replacement patterns to the last eight presidents—starting with Carter since he was the first president to prioritize diversity and implement a related appointment strategy (Goldman 1997). To do so, we employ a crude index of increasing diversity in which white males serve as the baseline and are coded zero. The index increases by one whenever a white man is replaced by a white woman or man of color or if a white woman is replaced by a woman of color. The index increases by two if a white man is replaced by a woman of color (intersectionality). The index is scored the same way in reverse. Accordingly, if a white man replaces a woman of color, the index drops two points (see Solberg and Diascro 2020).[17]

The data in table 11 below clearly show that President Trump’s flouting of diversity as a consideration in his judicial appointments is not by accident. While his cohorts resemble those of Reagan or G. H. W. Bush, demographically speaking, the large-scale changes in the bench over time and the continued goal of presidents from both parties to increase the diversity of the bench—either because they are committed to increasing representation and opportunities for underrepresented groups, or because they are using judicial nominations as outreach to communities for their party, or both—reveal that President Trump is truly different in his approach and is bucking historical trends. Bluntly put, his increases in diversity are among the smallest on the list and compare poorly to these previous presidents. The lone exception to this statement may be Reagan, but even Reagan scored more “1s” than Trump in raw numbers and percentages. Trump, by far, has done the most to reduce diversity at a time when contributing to diversity is significantly easier, given the current demographics of the profession (see Carsh 2019, and Achury and Hofer 2020, this volume). Given the importance of diversity to representation and the legitimacy of institutions, the judiciary should be extremely concerned about this trend.

| President | Increase in diversity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 1 | 0 | -1 | -2 | Total* | |

| Carter | 4

3% |

37

29% |

85

66% |

2

1% |

0 | 128 |

| Reagan | 3

1% |

51

17% |

229

79% |

8

3% |

0 | 291 |

| G.H.W. Bush | 5

3% |

44

29% |

97

65% |

4

3% |

0 | 150 |

| Clinton | 13

4% |

143

42% |

172

50% |

16

5% |

0 | 344 |

| G.W. Bush | 12

4% |

90

30% |

178

60% |

13

4% |

5

2% |

298 |

| Obama | 28

9% |

141

43% |

130

40% |

28

9% |

1

>1% |

328 |

| Trump | 5

3% |

29

15% |

120

61% |

40

20% |

2

1% |

196 |

| Total | 70 | 535 | 1011 | 111 | 8 | 1735 |

* Total numbers for each president will not match overall appointments for two reasons. First, new seats are not included in this table. Second, some judges are counted twice in that they were appointed to two different courts by the same president. In other words, if President Clinton appointed someone to the district court in his first year and then elevated that same person to the court of appeals in his fifth year, that judge enters the dataset twice.

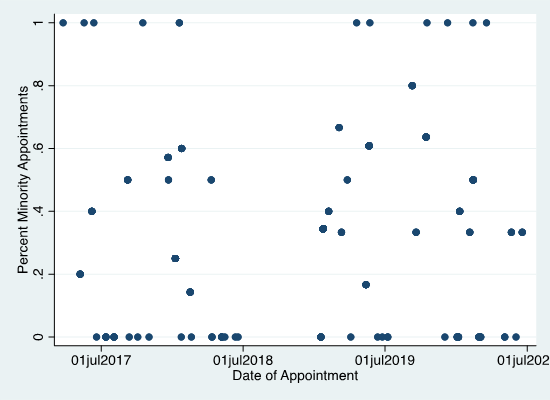

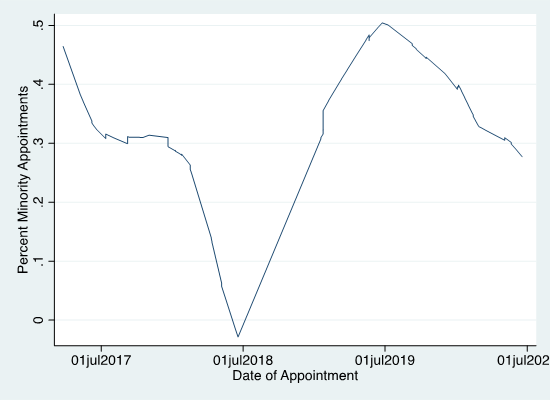

As we have mentioned several times now, Trump’s judicial cohort at either the courts of appeals or the district courts is not as monolithic as was predicted early in his administration (see Solberg and Waltenburg 2018a, b, and c.) While we make no claim that Trump’s judges are by any means as diverse as his recent predecessors, the apparent difference between those early predictions, supported by contemporaneous analyses, and the final tally leaves one wondering whether something changed or whether scholars were just too quick off the mark in making claims about Trump’s nominees. To investigate this small puzzle further, we collected data on the initial nomination for each of Trump’s successful judicial nominees as well as information on their self-identified gender and race.[18] Figure 1 displays a scatterplot of the percentage of Trump’s appointees who are women and/or judges of color over time, while figure 2 displays the results of using a statistical procedure that aids in identifying any signal or pattern in the data. Specifically, the procedure computes the best-fitting regression line for the dependent and independent variables for a given observation and then a small set of additional observations near that observation. The resulting estimations are then weighted so that the specific observation contributes the most to the estimated value of the line, while observations further away contribute less to the estimated value. Since the procedure estimates a series of local lines, it is able to follow the data much more closely than does the standard regression procedure.[19]

Although the scatterplot itself is quite noisy, figure 2 displays a discernable pattern: more women and judges of color[20] were appointed later in time than earlier. In other words, there does seem to be a shift as time passes. While we cannot say whether President Trump or his administration reacted to the coverage in various outlets alluding to the lack of diversity in his judicial nominees, we can say that as time passes Trump’s cohort was more diversified, yielding an overall cohort that was less white and less male than initially predicted.

Conclusion

In this paper, we took a deep look into the demographic diversity of President Trump’s successful lower court judges. As expected, we found that his judicial cohort is generally lacking in diversity. Indeed, he is appointing judges like it is 1989.[21] While it is reasonable to suggest that President Trump compares well with Presidents Reagan and G. H. W. Bush in terms of diversity, such a comparison ignores the thirty- to forty-year spread between the start of the Reagan presidency and the end of the Trump presidency. Recall that in 1980 few women were on the bench or attending law school. Sandra Day O’Connor became the first woman on the Supreme Court in 1981. Reagan’s selection pool was significantly smaller in terms of women and lawyers of color. While there are still significant pipeline problems (Carsh 2019; Achury and Hofer 2020, this volume), women now make up a majority of most law school cohorts, and lawyers and judges of color are easily found on both sides of the ideological aisle.[22] President Trump’s 2020 list of twenty potential justices is 25 percent people of color (four men and one woman) and 30 percent women (N = 6). Among the potential justices of color are people who self-identify as Asian American and Black; three judges are of Latin descent (Lagoa and Cruz are Cuban American, and Muniz’s family emigrated from Nicaragua).[23] Thus it is clearly possible to find conservative nominees that also serve to broaden the descriptive representation on the bench.

Exploring the demographics of Trump’s judges is more than an exercise in ranking presidents by their commitment to diversity. Diversity yields tangible benefits for the courts and for US citizens. Diversity has direct connections to diffuse support for the courts and legitimacy for the judiciary as a whole. While the courts still seem to enjoy greater support and trust than the rest of the federal government, this support is splintered by partisan affiliation.[24] This broad support can only be enhanced by interactions with courts and those interactions are affected by diversity (Lee et al. 2021). Litigants and lawyers before the federal courts are more likely to perceive the process as fair and equitable if the bench is diverse (Scherer and Curry 2010; Ulbig 2007). Thus the question of how diverse President Trump’s judges are has much broader implications than a commitment to equality and social justice. For example, Democrats are less likely to support a court because they perceive the courts as tilted by President Trump, but if those courts remain diverse and mirror the population, then some of that support may be regained.[25]

Learning Activity

- Break students into small groups and assign each group a district or circuit court. If it is a small class, you can just use the courts in your home circuit.

- Have the students use the Federal Judicial Center (FJC) website to examine the composition of their court before and after Obama’s appointments, before and after Trump’s appointments, and before and after Biden’s appointments.

- Students should then discuss how these appointments affected the diversity of the court. You could also have students investigate partisan balance or even the background of the judges appointed, since the FJC provides brief resumes for all confirmed judges.

- Reconvene as a class to discuss the results.

References

Baum, L. 2009. Judges and Their Audiences: A Perspective on Judicial Behavior. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Benson, C. R. 2007. “A Renewed Call for Diversity among Supreme Court Clerks: How a Diverse Body of Clerks Can Aid the High Court as an Institution.” Harvard BlackLetter Law Journal 23:23–54.

Bonneau, Chris W., and Melinda Gann Hall. 2009. In Defense of Judicial Elections. New York: Routledge.

Bouie, Jamelle. 2020. “Court Packing Can Be an Instrument of Justice.” New York Times, October 9, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/09/opinion/court-packing-amy-coney-barrett.html.

Boyd, Christina L., Lee Epstein, and Andrew D. Martin. 2010. “Untangling the Causal Effects of Sex on Judging.” American Journal of Political Science 54 (2): 389–411.

The Conversation. 2018. “Trump’s Presidency Marks the First Time in 24 Years that the Federal Bench Is Becoming Less Diverse.” June 11, 2018. https://theconversation.com/trumps-presidency-marks-the-first-time-in-24-years-that-the-federal-bench-is-becoming-less-diverse-97663.

Diamond, Irene. 1977. Sex Roles in the State House. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Diascro, Jennifer Segal, and Rorie Spill Solberg. 2009. “George W. Bush’s Legacy on the Federal Bench: Policy in the Face of Diversity.” Judicature 92:289–301.

Diascro, Jennifer Segal, and Rorie Spill Solberg. “George W. Bush’s legacy on the federal bench: Policy in the face of diversity.” Judicature 92 (2008): 289.

Easton, David. 1965. A Systems Analysis of Political Life. New York: Wiley.

Epstein, Rachel. 2020. “Kamala Harris Has Becomes the First Black, South Asian, Female Vice President-Elect.” Marie Claire, November 7, 2020. https://www.marieclaire.com/politics/a34607314/kamala-harris-vice-president-win-reactions/.

Garrett, Major. 2018. “Trump Sides with Putin over US Intelligence during Remarkable Press Conference in Helsinki.” CBS News, July 18, 2018. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/trump-sides-with-putin-over-u-s-intelligence-in-remarkable-helsinki-press-conference/.

Gay, Claudine. 2002. “Spirals of Trust? The Effect of Descriptive Representation between Citizens and Their Government.” American Journal of Political Science 46 (4): 717–32.

Golde, Kalvis. 2019. “Recent Polls Show Confidence in Supreme Court, with Caveats.” Scotusblog (blog), October 22, 2019. https://www.scotusblog.com/2019/10/recent-polls-show-confidence-in-supreme-court-with-caveats/.

Goldman, Sheldon, and Elliot Slotnick. 1999a. “Clinton’s Second Term Judiciary: Picking Judges Under Fire.” Judicature 82 (6): 264–84.

———. 1999b. “Picking Judges under Fire.” Judicature 82 (6): 265–84.

Goldman, Sheldon, Elliot Slotnick, Gerard S. Gryski, and Sara Schiavoni. 2007. “Picking Judges in a Time of Turmoil: W. Bush’s Judiciary during the 109th Congress.” Judicature 90 (6): 252–83.

Goldsmith, Jack. 2017. “Will Donald Trump Destroy the Presidency?” Atlantic, October 2017. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2017/10/will-donald-trump-destroy-the-presidency/537921/.

Grant, Tim. 2019. “Trump’s Refusal to Release His Tax Returns Breaks a Long Presidential Tradition.” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, May 6, 2019. https://www.post-gazette.com/news/politics-nation/2019/05/06/donald-trump-taxes-presidential-tax-law-ways-means-committee/stories/201904250114.

Hernandez, Salvador. 2020. “Here’s How Women Reacted to Kamala Harris Speaking for the First Time as the Vice President-Elect.” BuzzFeed News, November 7, 2020. https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/salvadorhernandez/kamala-harris-victory-speech-reaction.

Herring, Cedric. 2009. “Does Diversity Pay? Race, Gender, and the Business Case for Diversity.” American Sociological Review 74 (2): 208–24.

Janes, Chelsea. 2020. “Americans React to Kamala Harris’s Historic Victory: ‘Look Baby, She Looks like Us.’” Washington Post, November 7, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/reactions-kamala-harris-vice-president/2020/11/07/8eaad904-213a-11eb-90dd-abd0f7086a91_story.html.

Klein, D., and L. Baum. 2001. “Ballot Information and Voting Decisions in Judicial Elections.” Political Research Quarterly 54 (4): 709–28.

Lee, Claire, Rorie Spill Solberg, and Eric Waltenburg. 2021. “See Jane Judge: Descriptive Representation and Diffuse Support for a State Supreme Court.” Politics, Groups, and Identities. https://doi.org/10.1080/21565503.2020.1864651.

Mansbridge, Jane. 1999. “Should Blacks Represent Blacks and Women Represent Women? A Contingent ‘Yes.’” Journal of Politics 61 (3): 628–57.

Mauro, T. 2014. “Diversity and Supreme Court Law Clerks.” Marquette Law Review 98:361.

Pitkin, Hanna. 1967. The Concept of Representation. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Root, Danielle, Jake Faleschini, and Grace Oyenubi. 2019. “Building a More Inclusive Federal Judiciary.” Center for American Progress, October 3, 2019. https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/courts/reports/2019/10/03/475359/building-inclusive-federal-judiciary/.

Scherer, Nancy, and Brett Curry. 2010. “Does Descriptive Race Representation Enhance Institutional Legitimacy? The Case of the U.S. Courts.” Journal of Politics 72 (1): 90–104.

Solberg, Rorie Spill. 2005. “Diversity and G. W. Bush’s Judicial Appointments: Serving Two Masters.” Judicature 88:276–83.

Solberg, Rorie Spill, and Jennifer Segal Diascro. 2020. “A Retrospective on Obama’s Judges: Diversity, Intersectionality, and Symbolic Representation.” Politics, Groups, and Identities 8 (3): 471–87.

Solberg, Rorie Spill, and Eric N. Waltenburg. 2017. “Trump’s Judicial Nominations Would Put a Lot of White Men on Federal Courts.” Monkey Cage (blog). Washington Post, November 28, 2017. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2017/11/28/this-is-how-trump-is-changing-the-federal-courts/.

———. 2018a. “Are Trump’s Judicial Nominees Really Being Confirmed at a Record Pace? The Answer Is Complicated.” Monkey Cage (blog). Washington Post, June 14, 2018. https://themonkeycage.org/2018/06/are-trumps-judicial-nominees-really-being-confirmed-at-a-record-pace-the-answer-is-complicated/.

———. 2018b. “Trump’s Judicial Nominations Would Put a Lot of White Men on Federal Courts.” Monkey Cage (blog). Washington Post, November 17, 2017. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2017/11/28/this-is-how-trump-is-changing-the-federal-courts/.

———. 2018c. “Trump’s Presidency Marks the First Time in 24 Years that the Federal Bench Is Becoming Less Diverse.” The Conversation (blog), June 11, 2018. https://theconversation.com/trumps-presidency-marks-the-first-time-in-24-years-that-the-federal-bench-is-becoming-less-diverse-97663.

Spill, Rorie L., and Kathleen A. Bratton. 2001. “Clinton and Diversification of the Federal Judiciary.” Judicature 84 (5): 256–61.

Squire, Peverill. 1992. “Legislative Professionalization and Membership Diversity in State Legislatures.” Legislative Studies Quarterly 17 (1): 69–79.

Ulbig, Stacy G. 2007. “Gendering Municipal Government.” Social Science Quarterly 88 (8):1106–23.

Washington Post. 2017. “Trump Goes above and beyond to Break the Unwritten Rules of Governing.” January 31, 2017. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/trump-goes-above-and-beyond-to-break-the-unwritten-rules-of-governing/2017/01/31/46cd1fce-e7d3-11e6-b82f-687d6e6a3e7c_story.html.

———. 2020. “What Trump Officials Really Say—in Denying that He Disparaged Fallen Troops.” September 8, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2020/09/08/trump-officials-military-disparagement-denials/.

Wheeler, Russell. 2012. “Judicial Nominations and Confirmations in Obama’s First Term.” Brookings Institution, December 13, 2012. https://www.brookings.edu/research/judicial-nominations-and-confirmations-in-obamas-first-term/.

Wright, Katerina. 2017. “Norms Watch: Tracking Team Trump’s Breaches of Democratic Traditions.” Just Security (blog), January 13, 2017. https://www.justsecurity.org/36303/normalization-watch/.

- Washington Post (2017); Goldsmith (2017); Wright (2017). ↵

- Grant (2019); Washington Post (2020); Garrett (2018). Indeed, one blog (Just Security) set up a regular tracking series (“Norms Watch”) to monitor President Trump’s relationship to democratic norms. See Wright (2017). ↵

- The Conversation (2018); Solberg and Waltenburg (2017). ↵

- Though some research suggests that elected judges do respond more directly to public opinion the closer they are to reelection (Bonneau and Hall 2009) or consider certain audiences when deciding cases (Baum 2009). ↵

- The election of Kamala Harris as vice president of the United States provided plenty of anecdotal evidence for this claim. Witness the reports of women and girls noting that seeing a woman and a woman of color in this role made them feel that they could do anything—be anything. See Janes (2020); Hernandez (2020); Epstein (2020). ↵

- For example, there are 179 active judgeships on the US courts of appeals and, at the time of this writing, there were 117 senior status judges still serving. Thus the total number of courts of appeals judges working on cases is 298. ↵

- Our data collection ended on June 24, 2020, after Trump’s two hundredth judge was confirmed. ↵

- See Wheeler (2012). ↵

- While H. W. Bush comes the closest to matching Trump, the comparison is not a particularly good one. First, the polarization that characterizes the current judicial nomination process, and indeed, Congress in general, was not fully developed at the time. Second, H. W. Bush faced a Democrat majority for the entirety of his presidency. Third, the filibuster was still in place for the Bush presidency. ↵

- President Trump and his administration, with the assistance of the Republican majority in the Senate, did their utmost to ensure that there were few vacancies overall across the judiciary. As of this writing, there are currently seventy-eight vacancies with forty-eight pending nominations and three future vacancies. Given the total number of district court judges (N = 667 with an additional ten temporary judgeships), there are always vacancies on these courts. For comparison, when President Obama left office, there were eighty-six vacancies on the district courts, seventeen on the courts of appeals, and one on the US Supreme Court. ↵

- We make no comment or judgment about whether the Trump cohort is changing the partisan or ideological profile of the courts. We leave that work to others. ↵

- Carter’s appellate cohort was 78.6 percent white, which represented significant progress on diversity in the late 1970s. For comparison, Reagan and Bush’s appellate cohorts were 97.4 percent and 89.2 percent white, respectively (see Goldman and Slotnick 1999). ↵

- Root, Faleschini, and Oyenubi (2019). ↵

- The continued presence of women across these courts is likely a remnant of the diversification efforts of President Obama and Clinton. President Obama’s appellate judges were almost 44 percent women (noted above) and President Clinton’s cohort was 33 percent women (Goldman and Slotnick 1999). ↵

- We only focus on symbolic diversity here. We are not suggesting that President Trump’s nominees will have no discernable impact on the decision-making of these courts. ↵

- After all, when a district court judge is nominated for a seat on the appellate bench, she is said to be “elevated” to the courts of appeals. ↵

- We deem this a crude measure of diversity because our equivalence of men of color and white females is less than ideal; however, we believe this measure allows us to gain a sense of the trends in judicial appointments over time. ↵

- Again, this information was gleaned from the biographical database available from the Federal Judicial Center. In doing so, we also noticed that President Trump renominated thirteen judges that were initially nominated by President Obama. Given the vitriol that President Trump spewed about his predecessor and his judges, we were surprised there were so many. We do not know if this is de rigueur for presidents and intend to investigate this in future work. ↵

- See https://www.stata.com/manuals13/rlowess.pdf (last accessed November 26, 2020). ↵

- Previously, the literature has denoted this broad category as nontraditional. The term began as an easy way to class the few women and minority judges on the federal bench and because, due to discrimination in the legal field, these men and women tended to follow career paths divergent from their white and male counterparts. We eschew that term as it suggests that alternative career paths are somehow “not normal” and places the privileged path paved for white people and men as the normal. We believe this is changing, though slowly, and the literature needs to evolve as well. ↵

- Apologies to Prince and his iconic song “Party like It’s 1999.” ↵

- To further support this contention, we can look to the diverse cohort appointed by G. W. Bush, who valued ideology as well as diversity in his judicial nominees (see Solberg 2005). ↵

- It is interesting that Trump’s Supreme Court list has more Latinx representation than Asian American, since the latter demographic is the only one save white people that gained any representation under this president. ↵

- See Golde (2019). ↵

- During the 2020 campaign, some argued that GOP efforts to replace Justice Ginsburg should be met by Democrats with court packing to readjust the courts. See Bouie (2020). ↵