Actors in the Judicial Process

13 Identifying and Explaining the Prevalence of Political Backgrounds among U.S. Courts of Appeals Judges

Adam G. Rutkowski

Introduction

According to a statement released during his administration, former president Donald J. Trump was “committed to appointing judges who set aside their personal views and political prejudices to do what the Constitution and the law demand” (White House 2019). Despite this claimed focus on judicial impartiality, media outlets expressed concern that the president’s judicial picks—particularly his selections for the US Courts of Appeals—were more political than those of previous presidents (Ruiz et al. 2020). These allegations centered on the judges’ political backgrounds, such as partisan memberships, connections, and campaign activities.

One judge selected by President Trump particularly embodies these charges of heightened political prowess. John B. Nalbandian was nominated to the US Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit in January 2018 and confirmed five months later by a Senate vote of 53–45. Nalbandian’s tight vote margin could be a result of Democratic senators balking at his deep political background. Although he had served as a clerk for a US Court of Appeals judge and was a partner at an elite national law firm, a significant portion of Judge Nalbandian’s prebench career was spent supporting the Republican Party.

Over a 15-year period, Nalbandian was a member and chairman of the Commonwealth Political Action Committee, a member of the Boone County, Kentucky, GOP Executive Committee, and either an alternate or actual delegate to the 2008, 2012, and 2016 Republican National Conventions. Further, he served on the Executive Committee and as general counsel of the Republican Party of Kentucky. In this capacity, he advised the party generally and gave counsel to specific campaigns of politicians, including Senators Mitch McConnell and Rand Paul and Congressman Andy Barr. In private practice in Cincinnati, Ohio, Nalbandian worked for numerous Republican campaigns, including the Ohio branch of Romney for president. On a personal level, Nalbandian volunteered for numerous Republican campaigns at the state and federal levels (Senate Judiciary Committee 2021).

It is possible that the example of Judge Nalbandian’s political background is an extreme case. President Trump also selected judges with little to no prior political involvement. Amy St. Eve, confirmed to the Seventh Circuit in 2018, was a district judge on the US District Court for the Northern District of Illinois (nominated by President George W. Bush) prior to her elevation by President Trump. Starkly juxtaposed to Judge Nalbandian, Judge St. Eve has an almost imperceptible political background. Documents reveal she never ran for public office, never worked on behalf of a political party, and never belonged to a particular partisan organization (Senate Judiciary Committee 2021).

While judicial background scholarship addresses characteristics such as race, gender, age, education, judicial experience, and other career experiences, there has been less attention given to the political backgrounds of federal judges, particularly those judges on courts other than the Supreme Court. Accounts suggest that connections to political parties are important for potential judicial nominees (e.g., Tarr 2019; Carp et al. 2020; Goldman 1999), but a nuanced, wholesale account of judges’ political backgrounds is needed. The goal of this chapter is to address the following questions. How common are political backgrounds among the judges placed on the federal appellate bench? Is there variation among these backgrounds based on the nominating president? Do other background characteristics like race, gender, and professional experiences influence the presence of political backgrounds? Was Trump distinct in nominating more judges with political backgrounds? Answering these questions will provide a more complete look at judicial backgrounds and presidential selection of federal appellate judges.

I begin the chapter by arguing for the importance of considering political background in judicial studies and identifying key indicators of political activity using the information-rich Senate Judiciary Committee (SJC) questionnaires.

After a descriptive account of judges’ political backgrounds is presented, I examine how other background characteristics influence judges’ political backgrounds. The chapter concludes with a discussion of President Trump’s distinct impact on selecting politically active judges and a discussion of avenues for future research in this area.

An Important Piece of the Background Puzzle: Political Backgrounds

The presence of political backgrounds has been addressed in various ways in judicial politics scholarship. Goldman (1999) includes a measure called prominent party activism in his work that captures judges’ connections to senators and presidents. Indeed, Tarr notes that judges “usually have ‘earned’ their positions by active party service before their appointment” (2019, 70). Other scholars have addressed political experience in terms of partisanship and experience holding elected office (Brudney et al. 1999; Gryski, Main, and Dixon 1986; Vines 1964). While interesting and important, these studies examine areas of political experience that have more to do with connections to politicians and partisan labels. In the following section, I assert several reasons for considering political activity and identify sources and novel indicators that more directly capture judges’ political backgrounds.

The Importance of Treating Political Background as a Distinct Background Characteristic

At the outset, it is necessary to define political background. Political backgrounds can include any prior political activity, including holding positions in partisan campaigns, pursuing partisan nonjudicial elected office, or joining a partisan organization. While it is one thing to consider oneself a Democrat, it is another to have worked on numerous campaigns for Democratic candidates, run for office as a Democrat, and/or join a formal local or state Democratic organization. The activities and experiences making up a political background come together to form a distinct characteristic that is separate from other political characteristics like partisanship and ideology and is important to consider in judicial scholarship.

Political background is separate from the concepts of shared partisanship with the appointing president and ideology. Similar partisanship as the appointing president focuses more on partisan labels. It is not groundbreaking to state that Republican presidents select nominees with Republican leanings or that Democratic presidents select Democratic-leaning nominees. After all, selecting judges of the same party helps presidents secure a lasting judicial legacy (Solberg and Diascro 2018; Diascro and Solberg 2009; Goldman 1999). On the other hand, the political activities that make up a political background are tangible, lived experiences that judges have chosen to participate in and demonstrate a commitment to a political party. This commitment goes beyond simply calling oneself a Republican or Democrat. Partisanship is simply a label given to judges (usually by others besides the judges themselves). For example, many Americans consider themselves as belonging to one of the two major political parties. However, fewer people actually participate in partisan politics. Running for elected office, formally claiming party membership, and working on behalf of a political party via campaigning, fundraising, organizing, and so on demonstrate a commitment to a political party that goes beyond mere partisanship. These political background characteristics are real experiences that show a certain level of commitment to a party by the judge.

Political background is also distinct from ideology. Similar to partisanship, ideology deals with the political leanings of judges. It places judges on various political spectrums and is typically used in models of judicial behavior. It is typically measured using votes the justices have cast in cases while on the bench (e.g., Epstein et al. 2007; Martin and Quinn 2002) or the ideologies of the senators and president involved in their nominations and confirmations (Giles, Hettinger, and Peppers 2001). These ideological measures do not take into account the political activity they participated in prior to joining the bench. Again, a political background represents actions taken by judges in the political realm.

In addition to being distinct from other key concepts of judicial scholarship, political background is important to study for a couple of practical reasons. First, if political backgrounds are more common now (or even if they have been common for many years), this suggests a changing path to the federal bench. As indicated in the previous section on common background characteristics, it is normally professional experiences and qualifications that are considered the typical first steps to a federal judgeship. While it is unsurprising that people with political connections get selected for the political process of judicial nominations, a wholesale account of what these connections are does not exist. Therefore, this chapter contributes to our understanding of how political backgrounds come into play on the road to judging.

Since political background is a distinct characteristic representing experiences judges have had prior to their appointment, it is possible that it could affect judicial behavior. Just as background characteristics like race, gender, prior judicial experience, academic experience, and prosecutorial experience have been shown to influence judicial behavior (e.g., Boyd 2016; Boyd and Rutkowski 2020; Boyd, Epstein, and Martin 2010; Crowe 1999; Farhang and Wawro 2004; Haire and Moyer 2015; Kastellec 2013), these political experiences could affect the way judges view cases. Participating in political activities suggests a political mindset with the potential to influence judges’ actions. In the following section, I further explicate the idea of political background by conceptualizing specific political background activities and discussing a rich source of this information.

Conceptualizing Political Backgrounds via Senate Judiciary Committee Questionnaires

Where can information on judges’ political backgrounds be found? While information may appear in news reports of judicial nominations or in datasets focusing on other background characteristics, a comprehensive source of information on this background has not been identified and coded in a way that directly captures political backgrounds. The most complete data source for judges’ political backgrounds is the Senate Judiciary Committee (SJC) questionnaires.[1]

Since around 1988, each federal judicial nominee has answered a similar set of 25 to 30 questions in the SJC questionnaires.[2] These questions cover everything from career experience, memberships, television appearances, published writings, judicial experience, and political activities. These are just a few of the many pieces of information that can be found about judges in these questionnaires. As Dancey, Nelson, and Ringsmuth (2020) point out, the SJC questionnaire is “long and thorough…‘monstrous’” (21). Asking similar questions of each nominee helps members of the Senate Judiciary Committee and the Senate at large make comparisons between nominees. This standardization also helps scholars make methodologically sound comparisons between judges over a 30-plus year timespan.

Even more important than their standardized form, these questionnaires are considered trustworthy (Dancey, Nelson, and Ringsmuth 2020; Rutkus 2016; Rutkus and Rybicki 2009). In other words, the information provided by the judges is thorough, accurate, and reliable. This accuracy makes these questionnaires robust sources of information on political backgrounds and other characteristics.

After spending time combing through the questionnaires to find evidence of political background, I discerned three key indicators of prior political activity. Considered together, these variables of interest account for the prior political involvement of judges. The indicators I selected come primarily from the following two questions:

List chronologically any public offices you have held other than judicial offices, including the terms of service and whether such positions were elected or appointed. If appointed, please include the name of the individual who appointed you. Also, state chronologically any unsuccessful candidacies you have had for elected office or unsuccessful nominations for appointed office.

List all memberships and offices held in and services rendered, whether compensated or not, to any political party or election committee. If you have ever held a position or played a role in a political campaign, identify the particulars of the campaign, including the candidate, the dates of the campaign, your title, and your responsibilities.

These questions provide information on nominees’ prior nonjudicial offices and their connections to political parties. From these questions, I developed variables capturing whether the judge pursued public office in the past, whether they claimed to be a member of a political party, and whether the judge worked for a party organization in the past.[3]

Elected office takes a value of (1) if the judge pursued elected office prior to their federal appellate judgeship and (0) otherwise. Running for Congress, a state legislative seat, and a local city council seat are all political activities. Pursuing public office suggests political ambition that is distinct from partisanship. It is one thing to be a Republican, but it is quite another to run for a legislative seat on the Republican ticket.

Party membership indicates whether the judge listed membership in a political party and is coded dichotomously. Party memberships can include memberships in the actual national party or membership in a partisan lawyer’s club.[4] Listing party membership is identified as a political activity because it represents a judge’s conscious choice to identify themselves with a party. While many people consider themselves as belonging to one party, formally joining the party represents a further step.

Party work is given a value of (1) if the judge listed work for a particular political campaign or politician and (0) otherwise. Examples of party work include serving as a delegate to a political convention, campaigning for a partisan candidate, participating in political fundraising activities, and volunteering for the party in other ways. Number of party work entries is a continuous variable that captures the number of entries of partisan work listed by the judge on their questionnaire. I include this continuous measure to capture variation in the amount of party work entries among federal judges.

A Descriptive Overview of the Political Backgrounds of US Courts of Appeals Judges

I ascertain how common political backgrounds are among federal judges by analyzing the confirmed Courts of Appeals judges of Presidents George H. W. Bush, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, Barack Obama, Donald Trump, and Joe Biden.[5] This provides 314 appellate judges confirmed between 1989 and 2022.

Table 1 provides the summary statistics of the novel political activity variables. First, consider the pursuit of elected office. It seems as if selecting judges who have pursued nonjudicial elective office is falling out of fashion. While the percentage of the judges of Presidents H. W. Bush, Clinton, and W. Bush who pursued partisan elected office prior to the bench hovers around 20%, only 7%, 6%, and 3%, respectively, of the succeeding presidents’ judges had this background experience.

| Elected office (%) | Party membership (%) | Party work (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| H. W. Bush | 17 | 24 | 57 |

| Clinton | 25 | 12 | 60 |

| W. Bush | 20 | 28 | 54 |

| Obama | 7 | 15 | 53 |

| Trump | 6 | 30 | 78 |

| Biden | 3 | 19 | 50 |

Note: This table shows the summary statistics of the political variables. N = 314 judges

A partisan divide appears when analyzing the percentage of judges listing party membership on their questionnaires. It appears that more judges appointed by Republican presidents are willing to claim party membership. Table 1 shows that 24% of H. W. Bush’s, 28% of W. Bush’s, and 30% of Trump’s judges claimed membership in a political party (almost always the Republican Party). On the other hand, only 12%, 15%, and 19% of Clinton’s, Obama’s, and Biden’s judges listed membership in a party on their questionnaire. Either Republican presidents are appointing more partisan judges, or nominees of Republican presidents are more willing to list party membership. Remember that the information provided in these questionnaires is controlled by the nominees themselves.

Perhaps the most interesting political activity is captured by the party work variable. At least 50% of all judges listed at least one instance of party work on their questionnaire, regardless of the appointing president. There is no clear trend present in the party work variable besides the fact that Donald Trump’s nominees had more party work experience overall. Indeed, 78% of Trump’s judges listed party work on their questionnaires. Roughly 55%–60% of George H. W. Bush, Clinton, and George W. Bush’s judges had this experience, while roughly 50% of Obama’s and Biden’s did. The fact that almost 80% of Trump’s judges listed party work gives some credibility to the charges mentioned in the introduction section that Trump appointed more politically active judges.

The descriptive analysis of prior political activities of federal appellate judges reveals several key insights. First, it appears that judges placed on the bench more recently are not as likely to have pursued nonjudicial political office. Table 1 reveals that the number of judges with prior pursuit of elected office is steadily declining. Second, a more partisan trend is seen in listing party membership on the SJC questionnaires. Consistently, more Republican-appointed judges claimed membership in a political party. Third, when considering party work, the judges of President Trump worked more often on behalf of a political party than the judges of the previous presidents, including previous Republican presidents. Overall, this section illustrates that political backgrounds are not uncommon. Although there are ebbs and flows in the presence of certain types of political activities based on the appointing president, a judge being selected with some kind of political background is not a rare event.

The Influence of Other Background Characteristics on Political Backgrounds

The next goal of this chapter is to determine the influence that other background characteristics have on judges’ political backgrounds. For example, are appellate judicial nominees with prior judicial experience less likely to have political backgrounds than nominees without that experience? I will explore the influence of this and other background factors in this section by analyzing the 314 judges confirmed to the federal bench between 1989 and 2022.[6]

Previously in the chapter, I identified three indicators of political background from the SJC questionnaires: whether or not the judge held nonjudicial elected office, whether or not the judge belonged to a party organization, and whether or not the judge worked on behalf of a political party. These indicators will serve as the dependent variables in this analysis. As a reminder, the variables are measured as follows: elected office takes a value of (1) if the judge pursued partisan nonjudicial elected office prior to their federal appellate judgeship and (0) otherwise. Party membership indicates whether the judge listed membership in a political party and is coded dichotomously. Party work is given a value of (1) if the judge listed work for a particular political campaign and (0) otherwise.

The independent variables focus on many aspects of judicial background: the partisanship of a judge’s nominating president, the judge’s confirmation environment, and the judge’s demographic and professional background characteristics. Republican president takes a value of (1) if the nominating president is a Republican (i.e., H. W. Bush, W. Bush, and Trump) and (0) if the president is a Democrat (i.e., Clinton, Obama, and Biden). It would be possible to have the appointing president represented by a five-category factor variable to pick up nuances between presidents. However, given the similarities in appointing behavior based on the partisanship of the president (e.g., Goldman 1999), it makes sense to place them in this partisan dichotomy.

Divided government represents situations where the presidency and Senate are controlled by two different parties. It takes a value of (1) if there is split partisan control of the Senate and the presidency and (0) when the two institutions are controlled by the same party. It is important to note that divided government between the Senate and the president was rare during this 30-year time period.

In 2013, Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-NV) activated the nuclear option, which lowered the cloture requirement for ending debate on judicial nominees from 60 to 51 votes. Republican Mitch McConnell has kept the nuclear option in place, although he was adamantly opposed to the practice when Harry Reid and the Democratic-controlled Senate instituted it. Boyd, Lynch, and Madonna (2015) find that while the nuclear option did not produce more ideologically extreme nominees, it did lead to speedier confirmation durations. In short, the nuclear option is believed to make it easier to get judges confirmed. The nuclear option variable takes a value of (1) if the nomination happened after the 2013 nuclear option and (0) otherwise.

I also include several variables capturing professional and demographic background characteristics. Judicial experience takes a value of (1) if the nominee had served as a judge prior to their nomination to the US Courts of Appeals and (0) otherwise. Prosecutorial experience is assigned a value of (1) if the nominee had served in a prosecutorial role prior to their nomination and (0) otherwise. Gender takes a value of (1) if the nominee is female and (0) if the nominee is male. Minority takes a value of (1) if the nominee is a racial minority and (0) if the nominee is white. Age is a continuous variable measuring the age of the judge at their nomination. Data for these variables come from the Federal Judicial Center’s biographical data on federal judges (Federal Judicial Center 2022).

Results of Multifactor Analysis

Table 2 presents the results of the multifactor background analysis. Given the dichotomous nature of the dependent variables, I utilize logistic regression. Each column contains a different model with a different dependent variable. Model 1 uses elected as the dependent variable, model 2 uses party member, and model 3 uses party work. The independent variables representing other background characteristics are the same for each model.

| Model 1 DV = elected |

Model 2 DV = party member |

Model 3 DV = party work |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Republican president | −0.23

(0.37) |

0.51*

(0.34) |

−0.21

(0.28) |

| Divided government | 0.32

(0.39) |

−0.10

(0.35) |

−0.11

(0.29) |

| Nuclear option | −0.88*

(0.54) |

0.38

(0.35) |

0.61**

(0.31) |

| Judicial experience | 0.20

(0.37) |

0.15

(0.31) |

0.15

(0.26) |

| Prosecutorial experience | −0.10

(0.37) |

−0.37

(0.30) |

−0.59**

(0.25) |

| Gender | −1.19***

(0.46) |

−0.34

(0.34) |

−0.68***

(0.28) |

| Minority | −2.05***

(0.77) |

−0.84**

(0.42) |

−1.24***

(0.31) |

| Age | 0.05*

(0.03) |

0.01

(0.03) |

−0.01

(0.02) |

| Constant | −3.51**

(1.88) |

−1.97

(1.41) |

1.59

(1.10) |

Note: This table shows the logistic regression results from three different models.

*** p ≤ 0.01, ** p ≤ 0.05, * p ≤ 0.1. N = 273

First, consider model 1. When using whether or not the judge pursued nonjudicial elected office as the dependent variable, the nuclear option, gender, race, and age have significant effects. Since the nuclear option was instituted in 2013, the negative coefficient suggests that it is less likely that a judge has the political background of pursuing elected office.[7] Further, women and minority nominees were less likely to have this political background characteristic. This is perhaps due to the historical reluctance of members of these groups to run for public office (Fox and Lawless 2010, 2014; Lawless and Fox 2005, 2010, 2012; Sen 2017). Age has a positive and significant effect on having elected office experience. It appears that older judges (when nominated) were more likely to have pursued nonjudicial partisan elected office.

Now consider model 2, where party membership is used as the political background–dependent variable. Recall that party member captures whether or not the judge listed membership in a political party on their SJC questionnaire. While neither of the confirmation environment variables (divided government and nuclear option) had meaningful effects, whether or not the appointing president is a Republican has a positive and significant effect on listing party membership. This suggests that Republican presidents are more likely to select judges who are stated members of a political party (usually the Republican Party). This comports with Goldman’s (1999) expectation that Republican presidents in particular select judges with conservative judicial philosophies and partisanship. Interestingly, minority and female judges are less likely to state their partisanship.

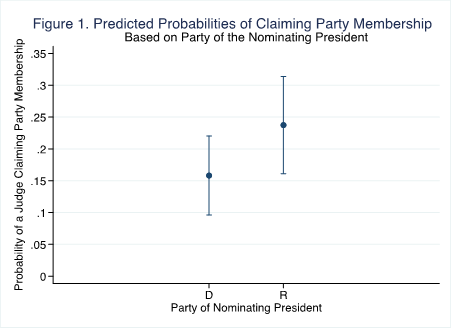

To help understand the results from model 2 in table 2, I plot predicted probabilities. While the coefficients in table 2 help discern the direction and significance of effects, predicted probabilities provide understandable and visualizable representations of a variable’s substantive effects based on the model results.

Figure 1 plots the predicted probabilities of claiming party membership based on the party of the appointing president. A Democrat-appointed judge has a 15% probability of claiming party membership, while a Republican-appointed judge has a 24% probability of claiming party membership. This substantial nine-point difference suggests that Republican nominees are significantly more likely to embrace their partisanship during the nomination/confirmation process.

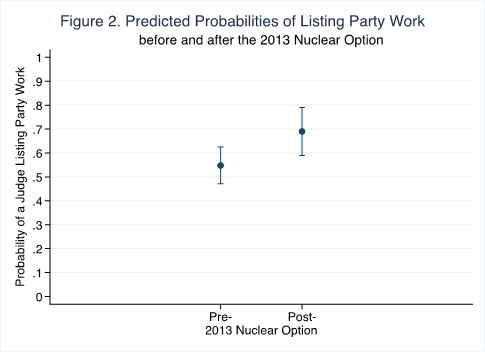

Model 3 in table 2 uses the party work political background characteristic as the dependent variable. Republican presidents are neither more nor less likely to select judges with past political party work. In terms of the confirmation environment background variable, the likelihood of a president appointing a judge with past party work increased significantly after the nuclear option was put in place. With the ease of pushing nominees through the confirmation process given this procedural change, presidents might be freer to select politically active judges.

Figure 2 plots the predicted probability of a nominee listing party work both before and after the 2013 nuclear option was instituted. Prior to the nuclear option, judges had a 55% probability of listing party work. However, after the nuclear option, this probability leaps to 70%. This 15-point difference suggests that the nuclear option made it easier for presidents to choose nominees with deeper political backgrounds.

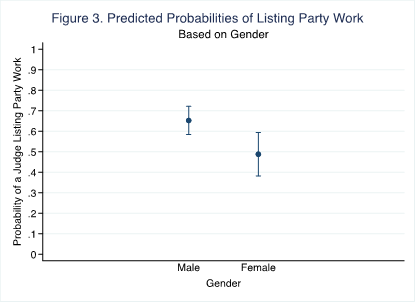

Prior prosecutorial experience had a negative and significant effect on a judge listing party work. Nominees with this experience were less likely to list this type of political background activity. Further, both women and racial minorities are less likely to report working on behalf of a political party. Again, this is probably due to the world of American politics being dominated by whites and males. The differences between white and nonwhite nominees provide the starkest effect. Figure 3 plots the predicted probabilities of listing party work based on gender. A male judge had a 65% probability of listing party work, while a female judge only had a 49% probability of listing party work in their questionnaire.

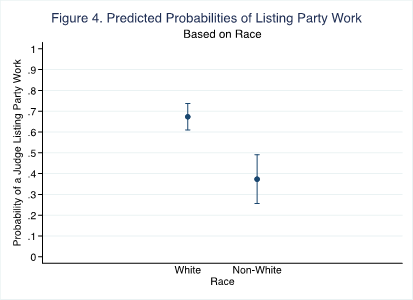

Figure 4 plots the predicted probabilities of listing party work based on race. While a white judge had an almost 70% probability of listing party work, a nonwhite judge only had a 39% probability of doing so.

These findings on race and gender are mostly consistent throughout the models. Coupled with the finding from model 3 that the nuclear option led to more judges with party work experience being nominated, the fact that women and minority judges were less likely to have this experience is even more striking. Under this procedural change, presidents are perhaps emboldened to select judges with political backgrounds (particularly President Trump; Jeknic et al. 2020). These judges are more likely to be white males.

President Trump’s Distinct Effect?

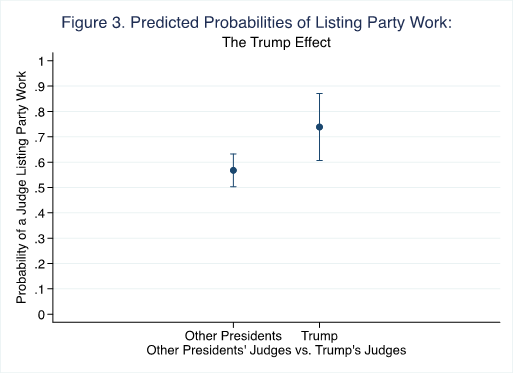

Results from model 3 in table 2 suggest that the nuclear option led to more judges with party work experience being placed on the federal appellate bench. It is plausible that the nuclear option’s effects on listing party work are actually capturing the effects of President Trump nominating more politically active judges, as suggested in the introduction section (Ruiz et al. 2020). This begs the question, Did Trump have a distinct impact?

To address this question, I construct another model, replacing the nuclear option variable with a dichotomous variable accounting for President Trump. Trump takes a value of (1) if the judge was nominated by President Trump and (0) otherwise. Party work is used as the dependent variable, and all other independent variables are the same as those used in the models in table 2.

| DV = Party Work | |

|---|---|

| Judicial experience | 0.05

(0.26) |

| Prosecutorial experience | −0.55**

(0.25) |

| Divided government | −0.15

(0.28) |

| Trump | 0.77**

(0.38) |

| Gender | −0.44*

(0.26) |

| Minority | −0.99***

(0.28) |

| Age | −0.00

(0.02) |

| Constant | 1.15

(1.04) |

Note: This table shows the logistic regression results from the Trump model.

*** p ≤ 0.01, ** p ≤ 0.05, * p ≤ 0.1. N = 273

Table 3 shows that President Trump’s judges were significantly more likely to list party work on their questionnaires than the judges of all other presidents, both Republican and Democrat. As in model 3 from table 2, former prosecutors, women, and minorities were less likely to list party work.

Figure 5 plots the predicted probabilities of listing work for a political party based on whether the nominating president was Trump or not. When considered as a group, the judges nominated by the five presidents preceding President Trump had about a 58% probability of listing party work. This includes President Biden, who was operating under the same nuclear option rules that Trump was. In contrast, President Trump’s judges had a 74% probability of having party work in their political background. This 16-percentage-point difference is statistically significant and gives validity to claims that President Trump placed more politically active judges on the bench during his time in office.

Discussion and Conclusion

In this chapter, I illustrated that political backgrounds are not uncommon among federal appellate judges appointed during the previous five presidential administrations. I developed a set of three indicators of political background (pursuit of nonjudicial elected office, claiming membership in a political party, and listing work on behalf of a political party or candidate) using the information-rich SJC questionnaires. I offered both descriptive analyses of the political background indicators and a multifactor regression analysis of the characteristics that influence the presence of political backgrounds among federal judges.

Results suggest that although political backgrounds are not unusual, there is significant variation based on other background characteristics and the type of political background being considered. The first political background indicator, pursuing nonjudicial partisan elected office, is a diminishing background characteristic and is conditioned by the race, gender, and age of the judge. The second political background indicator, claiming party membership, is most common among judges appointed by Republican presidents and is also conditioned by race and gender. The final political background trait of listing party work was more prevalent after the 2013 nuclear option was established and was conditioned by professional experiences in addition to race and gender. Further, Trump had a distinct impact on the federal appellate bench by selecting more judges with party work experience than any other president, whether Republican or Democrat. However, his influence only stood out with that one particular political background dimension.

Although there is a great deal of nuance among the findings presented in this chapter, the primary takeaways can be stated as follows: (1) political backgrounds are prevalent among federal judges, (2) the presence of these backgrounds is conditioned by other background factors, and (3) media charges that Trump’s judges are more political are true to some extent.

Future research should continue the study of political backgrounds by analyzing the questionnaires more closely. It is important to remember that these questionnaires are self-reported. While one expects the nominees to be forthcoming about their pasts, and research has found these questionnaires to be reliable (Rutkus 2016), there is technically room for manipulation. There has been at least one controversy in which a federal judicial nominee has been accused of withholding information from the SJC on their questionnaire. Recently, Wendy Vitter, a Trump District Court nominee, was criticized for leaving several antiabortion speeches off her questionnaire (Sherman 2018). In addition to the potential to control what information is included (though, again, this is limited), nominees can also choose how to describe that information. Textual analysis could be a fruitful avenue of research for these rich documents.

Scholars should ultimately use judges’ political background information to see how their decisions are affected. Is it possible that judges with deep political backgrounds will decide cases differently than those without a political past? Overall, this chapter stresses the importance of considering who presidents nominate to the federal appellate bench, and the results provide deeper insights into the political backgrounds of federal judges. To understand the pasts of judges is to understand how they can be expected to behave on the bench and ultimately influence legal policy.

Learning Activity

In this activity, you will take on the role of a political scientist coding political background characteristics of the current president’s Courts of Appeals judges.

- Navigate to the “Confirmation Listing” page on the US courts website (link: https://www.uscourts.gov/judges-judgeships/judicial-vacancies/confirmation-listing). This page provides a list of all judges confirmed to the federal appellate bench during the present Congress.

- Identify the judges that were confirmed to a federal circuit court (hint: look for the “CCA” denotation under the “Court” column).

- Record the names of the circuit court nominees in a table like the one below. Make a table with three columns with the headers “Judge Name,” “Party Membership,” and “Party Work.” For this step, just focus on “Judge Name.” The other columns will be addressed in Step 5.

Judge name (last, first) Party membership Party work – – – – – – – – – – – – - Navigate to the questionnaires page on the Senate Judiciary Committee’s website (link: https://www.judiciary.senate.gov/committee-activity/library?c=all&type=committee_questionnaire). Locate the questionnaires of the judges identified in your table and save them as pdf files.

- Code two of the political background variables identified in this chapter: party membership and party work. Coding rules: party membership captures membership in a national party organization. This could be a partisan lawyers club (e.g., Republican National Lawyers Association) or other clubs or organizations that are clearly affiliated with the Republican or Democratic Party. This information can usually be found in question 11 or 15 in the questionnaire. If a judge has this experience, enter a 1 in the corresponding cell. If they do not, enter a 0. Party work captures engagement in political activities on behalf of a political party or candidate. This includes campaigning for a candidate, hosting or organizing a political fundraiser or other political campaign event, assisting an election committee, and so on. This information can usually be found in questions 15, 16, and 17 of the questionnaires. If a judge has at least one instance of party work, enter a 1 in the corresponding cell. If they do not, enter a 0.

- Once the data are collected, calculate summary statistics and compare the political backgrounds of the sample of recently confirmed judges to the judges discussed in the chapter.

References

Bird, Christine C., and Zac A. McGee. 2023. “Going Nuclear: Federalist Society Affiliated Judicial Nominees’ Prospects and a New Era of Confirmation Politics.” American Politics Research 51(1): 37–56.

Boyd, Christina L., 2016. “Representation on the Courts? The Effects of Trial Judges’ Sex and Race.” Political Research Quarterly 69(4): 113–41.

Boyd, Christina L., Paul M. Collins Jr., and Lori A. Ringhand. 2018. “The Role of Nominee Gender and Race at U.S. Supreme Court Confirmation Hearings.” Law & Society Review 52(4): 871–901.

Boyd, Christina L., Lee Epstein, and Andrew D. Martin. 2010. “Untangling the Causal Effects of Sex on Judging.” American Journal of Political Science 54(2): 389–411.

Boyd, Christina L., Michael S. Lynch, and Anthony J. Madonna. 2015. “Nuclear Fallout: Investigating the Effect of Senate Procedural Reform on Judicial Nominations.” Forum 13(4): 623–41.

Boyd, Christina L., and Adam G. Rutkowski. 2020. “Judicial Behavior in Disability Cases: Do Judge Sex and Race Matter?” Politics, Groups, and Identities 8(4): 834–44.

Brudney, James J., Sara Schiavoni, and Deborah J. Merritt. 1999. “Judicial Hostility toward Labor Unions—Applying the Social Background Model to a Celebrated Concern.” Ohio State Law Journal 60(5): 1675–1771.

Carp, Robert A., Kenneth L. Manning, Lisa M. Holmes, and Ronald Stidham. 2020. Judicial Process in America: Eleventh Edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: CQ Press.

Collins, Paul M., and Lori A. Ringhand. 2013. Supreme Court Confirmation Hearings and Constitutional Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Crowe, Nancy. 1999. “The Effects of Judges’ Sex and Race on Judicial Decision Making on the U.S. Courts of Appeals, 1981–1996.” PhD diss., University of Chicago.

Dancey, Logan, Kjersten R. Nelson, and Eve M. Ringsmuth. 2014. “Individual Scrutiny or Politics as Usual? Senatorial Assessment of U.S. District Court Nominees.” American Politics Research 42(5): 784–814.

Dancey, Logan, Kjersten R. Nelson, and Eve M. Ringsmuth. 2020. It’s Not Personal: Politics and Policy in Lower Court Confirmation Hearings. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Diascro, Jennifer Segal, and Rorie Spill Solberg. 2009. “George W. Bush’s Legacy on the Federal Bench: Policy in the Face of Diversity.” Judicature 92: 289–301.

Epstein, Lee, Andrew D. Martin, Jeffrey A. Segal, and Chad Westerland. 2007. “The Judicial Common Space.” Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization 23: 303–25.

Farhang, Sean, and Gregory Wawro. 2004. “Institutional Dynamics on the U.S. Court of Appeals: Minority Representation under Panel Decision Making.” Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization 20: 299–330.

Federal Judicial Center. 2022. “Biographical Directory of Article III Federal Judges, 1789–Present.” https://www.fjc.gov/history/judges (last accessed June 1, 2023).

Fox, Richard L., and Jennifer L. Lawless 2010. “If Only They’d Ask: Gender, Recruitment, and Political Ambition.” The Journal of Politics 72(2): 310–26.

Fox, Richard L., and Jennifer L. Lawless. 2014. “Uncovering the Origins of the Gender Gap in Political Ambition.” American Political Science Review 108(3): 499–519.

Giles, Michael W., Virginia A. Hettinger, and Todd Peppers. 2001. “Picking Federal Judges: A Note on Policy and Partisan Selection Agendas.” Political Research Quarterly 54(3): 623–41.

Goldman, Sheldon. 1967. “Judicial Appointments to the United States Courts of Appeals.” Wisconsin Law Review 1967(4): 186–214.

Goldman, Sheldon. 1974. “Judicial Backgrounds, Recruitment, and the Party Variable: The Case of the Johnson and Nixon Appointees to the United States District and Appeals Courts.” International Society of Barristers Quarterly 9(3): 58–70.

Goldman, Sheldon. 1978. “A Profile of Carter’s Judicial Nominees.” Judicature 62: 246–54.

Goldman, Sheldon. 1999. Picking Federal Judges: Lower Court Selection from Roosevelt through Reagan New Haven: Yale University Press.

Goldman, Sheldon, and Elliot Slotnick. 1997. “Clinton’s First Term Judiciary: Many Bridges to Cross.” Judicature 80: 254–73.

Gryski, Gerard S., Eleanor C. Main, and William J. Dixon. 1986. “Models of State High Court Decision Making in Sex Discrimination Cases.” The Journal of Politics 48(1): 143–55.

Haire, Susan B., and Laura P. Moyer. 2015. Diversity Matters: Judicial Policy Making in the US Courts of Appeals. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press.

Jeknic, Petar, Rorie Spill Solberg, Eric Waltenburg, and Christopher Stout. 2020. “Trump’s Judges and Diversity.” In Open Judicial Politics, 3rd ed., edited by Rorie Spill Solberg and Eric Waltenburg, 201–22. Oregon State University.

Kastellec, Jonathan P. 2013. “Racial Diversity and Judicial Influence on Appellate Courts.” American Journal of Political Science 57(1): 167–83.

Lawless, Jennifer L., and Richard L. Fox. 2005. It Takes a Candidate: Why Women Don’t Run for Office. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lawless, Jennifer L., and Richard L. Fox. 2010. It Still Takes a Candidate. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lawless, Jennifer L., and Richard L. Fox. 2012. “Men Rule: The Continued Under-representation of Women in US Politics.” Women and Politics Institute. https://www.american.edu/spa/wpi/upload/girls-just-wanna-not-run_policy-report.pdf (last accessed July 3, 2024).

Martin, Andrew D., and Kevin M. Quinn. 2002. “Dynamic Ideal Point Estimation via Markov Chain Monte Carlo for the U.S. Supreme Court, 1953–1999.” Political Analysis 10: 134–53.

Ringhand, Lori A., and Paul M. Collins Jr. 2010. “May It Please the Senate: An Empirical Analysis of the Senate Judiciary Committee Hearings of Supreme Court Nominees, 1939–2009.” American University Law Review 60: 589.

Ruiz, Rebecca R., Robert Gebeloff, Steve Elder, and Ben Protess. 2020. “A Conservative Agenda Unleashed on the Federal Courts.” New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/14/us/trump-appeals-court-judges.html (last accessed October 1, 2022).

Rutkus, Denis Steven. 2016. “The Appointment Process for U.S. Circuit and District Court Nominations: An Overview.” CRS Report for Congress 7-5700. Congressional Research Service, Washington.

Rutkus, Denis Steven, and Elizabeth Rybicki. 2009. “Presidential Nomination, the Judiciary Committee, Proper Scope of Questioning of Nominees, Senate Consideration, Cloture, and the Use of the Filibuster.” CRS Reports for Congress 7-5700. Congressional Research Service, Washington.

Scherer, Nancy, and Banks Miller. 2009. “The Federalist Society’s Influence on the Federal Judiciary.” Political Research Quarterly 62(2): 366–78.

Sen, Maya. 2017. “Diversity, Qualifications, and Ideology: How Female and Minority Judges Have Changed, or Not Changed, Over Time.” Wisconsin Law Review 2017(3): 367–400.

Senate Judiciary Committee. https://www.judiciary.senate.gov (last accessed June 1, 2023).

Sherman, Cater, and Taylor Dolven. 2018. “A Trump Judge Pick Left Anti-abortion Speeches off Her Senate Disclosure Form.” Vice News. https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/vbpndy/a-trump-judge-pick-left-anti-abortion-speeches-off-her-senate-disclosure-form (last accessed March 1, 2021).

Solberg, Rorie Spill, and Jennifer Segal Diascro. 2018. “A Retrospective on Obama’s Judges: Diversity, Intersectionality, and Symbolic Representation.” Politics, Groups, and Identities 8(3): 471–87.

Tarr, G. Alan. 2019. Judicial Process and Judicial Policymaking: Seventh Edition. New York: Routledge.

Vines, Kenneth N. 1964. “Federal District Judges and Race Relations Cases in the South.” The Journal of Politics 26(2): 338.

White House. 2019. “President Donald J. Trump Is Appointing a Historic Number of Federal Judges to Uphold Our Constitution as Written.” https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/president-donald-j-trump-appointing-historic-number-federal-judges-uphold-constitution-written/ (last accessed April 1, 2023).

- Recent groundbreaking work has been done on confirmation hearings of lower court and Supreme Court judicial nominees (e.g., Boyd, Collins, and Ringhand 2018; Collins and Ringhand 2013; Dancey, Nelson, and Ringsmuth 2014, 2020; Ringhand and Collins 2010). These studies focus more on the interactions between senators and nominees. I use questionnaires as my source of information, given that I am focused on objective background characteristics. ↵

- Questionnaires have been around since the 1970s but have been used consistently since the late 1980s (Dancey, Nelson, and Ringsmuth 2020). They are publicly available on the Senate Judiciary Committee’s web page (https://judiciary.senate.gov). Other studies of judicial background and political connections also use the questionnaires (e.g., Goldman 1999, 1978, 1974, 1967; Goldman and Slotnick 1997). ↵

- This information is available consistently in the SJC questionnaires across the years they are available. ↵

- This variable does not capture membership in the Federalist Society. This conservative legal organization has had a significant influence on the judicial nomination and confirmation processes during Republican administrations. In this chapter, I am only considering party organizations with the name of a recognized American political party in the title. For scholarship on the Federalist Society’s impact on the federal judiciary, see Bird and McGee 2023 and Scherer and Miller 2009. ↵

- I analyze confirmed judges for two reasons: first, I am concerned with how these political activities can ultimately affect judges’ decisions. Unconfirmed nominees do not have the chance to influence policy. Second, finding the questionnaires is tedious work, and the unconfirmed nominees’ questionnaires are often unavailable. ↵

- I am not theorizing why or how these other background factors influence the presence of political backgrounds. I am offering an exploratory analysis of the relationship between political backgrounds and other commonly researched judicial background variables. ↵

- This negative coefficient is somewhat counterintuitive given that the coefficients for the nuclear option variable are positive for the other two models (and even significant in model 3) and that one would expect more political judges to be nominated under a set of relaxed procedural rules. This difference could suggest a changing set of priorities for selection of federal judges. Presidents might be focusing more on “informal party loyalists” (as evidenced by the uptick in selecting judges with party work experience) rather than individuals who formally held office as members of a party. ↵