Actors in the Judicial Process

6 Intersectional Representation on State Supreme Courts

Greg Goelzhauser

The legal profession’s history of discrimination against women and people of color is well documented. But women of color face unique hurdles to equal professional treatment (see, e.g., Blackburne-Rigsby 2010; Burleigh 1988; Collins, Dumas and Moyer 2017; Smith 1997). An American Bar Association (2006) survey reports, for example, that lawyers who are women of color are more likely to face workplace harassment, receive insufficient professional mentoring, be denied high-profile client assignments, and receive negative performance evaluations. As one state judge put it, “Women of color in the justice system of our nation, whether judge, attorney, or court staff suffer a double disadvantage—gender discrimination and ethnic bias” (Aranda 1996, 29).

Although the study of state judicial diversification is thriving (e.g., Arrington 2018; Bratton and Spill 2002; Goelzhauser 2016; Graham 1990; Hurwitz and Lanier 2003; Reddick, Nelson, and Caufield 2009), much of it emphasizes single-axis representation, particularly the separate seating of women and people of color. In contrast, intersectionality research “emphasizes the interaction of categories of difference (including but not limited to race, gender, class, and sexual orientation” (Hancock 2007, 63–64). Scholars have noted in other contexts that the double disadvantage women of color experience conditions the relationship between institutions and representation.[1] As Scola concludes in a study of intersectional legislative representation, “The process seems to be more complex than what is captured by race/ethnicity or gender separately” (2013, 344). Thus it is imperative to examine whether institutional design choices differentially impact intersectional representation.

This chapter considers the relationship between judicial selection institutions and the representation of women of color on state supreme courts. It begins with an overview of intersectionality and the law and continues with a theoretical consideration of the connection between selection institutions and diversification. The subsequent empirical analysis offers two contributions. First, I highlight the groundbreaking women of color who diversified state supreme courts—a group of people who have largely not been recognized for their achievement. Second, using data from 1960 through 2016, I examine whether selection institutions are associated with intersectional differences in seating new state supreme court justices. The results suggest that women of color are more likely to be seated through appointment mechanisms. The results are similar for men of color, but white men are more likely to be seated through elections. Selection system differences are not associated with changes in the probability of seating white women. These findings contribute to the nascent literature on intersectional judicial representation (see, e.g., Collins and Moyer 2008; Haire and Moyer 2015; Hurwitz and Lanier 2008, 2017; Solberg and Diascro 2019). They also have important policy implications for designing judicial selection institutions.

Diversity, Intersectionality, and the Courts

Understanding judicial diversification is important for several reasons. As an initial matter, the descriptive representation of women and people of color in political institutions can increase trust, engagement, and perceptions of legitimacy (see, e.g., Bobo and Gilliam 1990; Broockman 2014; Gay 2002; Mansbridge 1999; Reingold and Harrell 2010; Wolak 2015).[2] With respect to the courts, for example, support for the judiciary increases among Black respondents with the number of Black judges (Scherer and Curry 2010). And regarding intersectional judicial representation in particular, scholars have suggested that increasing the number of women of color on the bench will “hold strong symbolic meaning, instill greater confidence in the courts for all the litigants who come before them, and increase general confidence in the system of democracy in the country” (Fricke and Onwuachi-Willig 2012, 1542).

Greater representation can also influence judicial decision-making. Crenshaw’s (1989) seminal article on the difficulty of proving intersectional discrimination claims highlights how a lack of perspective can shape legal doctrine. In one case involving alleged employment discrimination brought “on behalf of black women,” a federal district court held that plaintiffs were “not . . . allowed to combine [gender- and race-based] statutory remedies to create a new ‘super-remedy’ which would give them relief beyond what the drafters of the relevant statutes intended” (DeGraffenreid v. General Motors 1976, 143). Thus plaintiffs could raise separate gender and race discrimination claims but could not base a cause of action on intersectional discrimination. As a result, evidence of nondiscrimination against women (even if that evidence involved, for example, only white women) could be used to defeat gender discrimination claims, and evidence of nondiscrimination against people of color (even if that evidence involved, for example, only Black men) could be used to defeat race discrimination claims.

Empirical evidence also suggests that women of color fare worse in court. One early study of employment discrimination claims in California finds that win rates and damage awards are lower in cases brought by Black women than by Black men or other women (Oppenheimer 2003, 544–45). Analyzing a national sample of federal equal employment opportunity cases from 1965 through 1999, another study finds that intersectional discrimination claims are increasing but only about half as likely to succeed; moreover, women of color are less likely to win (Best et al. 2011). Furthermore, the results indicate that women of color are the least likely gender-race intersection to win. Although win rates are similar for men and women generally, the “intersectionality penalty” (1009) results in women of color faring worse than expected when examining the data through a single-axis framework.

There is mixed single-axis evidence on whether judges who are women (e.g., Gryski, Main, and Dixon 1986; Martin and Pyle 2005; Songer, Davis, and Haire 1994) or people of color (e.g., Farhang and Wawro 2004; Scherer 2005; Welch, Combs, and Gruhl 1988) decide cases differently. At the federal level, Black circuit court judges are more likely to support affirmative action policies, as are white judges assigned to a panel with a Black judge (Kastellec 2013). A study exploring the relationship between gender and judicial decision-making on federal circuit courts finds few differences between men and women overall but notes that women are more likely to support plaintiffs in gender discrimination cases, as are white judges assigned to a panel with a woman (Boyd, Epstein, and Martin 2010). At the state level, supreme court justices of color are more likely than white justices to overturn convictions (Bonneau and Rice 2009).

Race and gender differences are also manifest in other aspects of judicial behavior. For example, there are gender-based differences in the types of experience men and women bring to the bench (Martin 1990), state apex court justices who are women or people of color are more likely to dissent in cases that are salient to members of those groups (Szmer, Christensen, and Kaheny 2015), men and women have different opinion-writing styles (Davis 1992), federal circuit court panels that include women or people of color produce opinions with different characteristics regardless of whether a woman or person of color writes the opinion (Gill and Hall 2015), and judges of color are more likely “to adopt a nonmainstream approach” and “experiment with alternative theories” in sentencing guideline cases (Sisk, Heise, and Morriss 1998, 1459). Although much of this literature adopts a single-axis perspective, findings of difference are prominent.

As more women of color join the bench, scholars are increasingly studying the link between intersectionality and substantive judicial representation.[3] One study of judicial behavior in federal circuit court criminal cases finds that women of color are more likely than judges with other gender-race combinations to vote for defendants (Collins and Moyer 2008). Another study reports that Black women exhibit distinct tendencies to dissent from majority dispositions on state high courts (Szmer, Christensen, and Kaheny 2015). And an analysis of opinion content finds that intersectional representation has important implications for how many points of law judicial opinions cover (Haire, Moyer, and Treirer 2013). Furthermore, Black women are more likely than white men to vote liberally in gender discrimination cases decided by federal circuit courts (Haire and Moyer 2015).

Selection Institutions and Judicial Diversification

The literature on state court diversification emphasizes the potential importance of judicial selection institutions. While Article III judges are seated by presidential nomination and Senate confirmation, state judicial selection mechanisms vary considerably. The primary selection methods include unilateral gubernatorial or legislative appointment, commission-aided gubernatorial appointment, and contestable nonpartisan or partisan elections. Along with diversity, selectors emphasize characteristics such as experience, temperament, and ideology. Given that selection institutions are designed for myriad reasons, there is no strong a priori theoretical justification for rank ordering them with respect to success in promoting diversity—much less the representation of women of color in particular. The existing empirical evidence on the relationship between selection institutions and diversification offers some a posteriori guidance but is mixed.

Under commission-aided gubernatorial selection, interested lawyers apply to fill a judicial vacancy, a commission typically comprising lawyers and nonlawyers selects a short list of nominees from the applicant pool, and the governor appoints one of the nominees. Early proponents of “merit selection” argued that it would prioritize qualifications over political connections. After President Carter experimented with commissions to help diversify the federal bench, supporters argued that use of the system would enhance representation for historically disadvantaged groups at the state level. The core argument is that emphasizing qualifications over political connections increases opportunities for marginalized groups. Capturing the prevailing sentiment among many merit selection proponents, one scholar argues, “There is no question but that the merit selection system affords greater opportunities for women and minorities to find their way to the bench” (Krivosha 1987, 19). Although arguments concerning merit selection rarely focus on intersectional representation in particular, perhaps the broader emphasis on diversity increases opportunities for women of color.

Proponents of other selection systems are typically less explicit about whether or how their favored mechanisms impact diversity. A possible benefit of unilateral elite appointment systems is that selectors are free to seek out prospective judges from the broader pool of qualified attorneys. Whereas choice is constrained under merit selection by applicant and nominee pools, and in elections by who runs for office, unilateral appointers can reach out to individuals who may not otherwise seek judgeships. This may be particularly important for attracting members of doubly disadvantaged groups. Unilateral appointment systems also facilitate holding stakeholders accountable for a lack of diversity. In merit selection systems, for example, it may be difficult to observe the extent to which a lack of diversity is due to pool imbalance, nomination decisions, or appointment decisions. In election systems, responsibility for a lack of diversification is likely to be more diffuse. Conversely, critics of unilateral elite appointment contend that unconstrained selectors use their power for patronage, in which case women of color may be disfavored due to their historical political underrepresentation.

Numerous arguments have been made for (e.g., Bonneau and Hall 2009) and against (e.g., Geyh 2003) judicial elections. However, this debate typically emphasizes issues such as voter knowledge, campaign dynamics, and legitimacy rather than diversity (see, e.g., Bonneau and Cann 2015; Cann and Yates 2016; Gibson 2012; Hall 2015). Two features of the broader political landscape drive concerns about elections and diversity. First, women and people of color may be more reluctant to run for office (e.g., Fox and Lawless 2005). Second, implicit bias may suppress support for underrepresented candidates (e.g., Weaver 2012). One scholar offered a hypothetical rebuttal to diversity arguments against judicial elections, suggesting that appointments “will often be white-shoe affairs subject to capture and cronyism and liable to scant diversity along any number of dimensions,” while “elections, at least, are covered by the Voting Rights Act” (Pozen 2008, 295). More practically, judicial elections may be uniquely suited to generate quick and sizeable increases in diversity. In 2018, for example, seventeen Black women were elected to the bench in Harris County, Texas (encompassing Houston), representing an 850 percent increase in the number serving (Schneider 2019).

The existing empirical literature offers insight into the relationship between selection institutions and state court diversification. Using a variety of samples and modeling strategies, numerous studies find no relationship between selection system choice and judicial diversity (e.g., Alozie 1990, 1996; Graham 1990; but see Martin and Pyle 2002). For example, selection system choice is largely unassociated with the pace at which states first diversified their apex courts (Goelzhauser 2011). And there is no consistent relationship between selection institutions and the number of women or people of color serving on state supreme courts in 1985, 1999, or 2005 (Hurwitz and Lanier 2003, 2008).

The most comprehensive studies leverage decades of data on state supreme court seatings to better understand the relationship between selection institutions and diversification. Examining seatings from 1980 through 1997, Bratton and Spill (2002) find that appointment systems are more likely to produce justices who are women. And data on seatings from 1960 through 2014 suggest that women are more likely to be seated under unilateral elite appointment than merit selection, with no meaningful difference between merit selection or unilateral appointment and elections; furthermore, people of color are more likely to be seated under unilateral elite appointment or merit selection than elections, with no discernable difference between appointment systems (Goelzhauser 2016).

Other research streams yield important insights about specific selection mechanisms and diversity. Under merit selection, for example, there is evidence that commissions are less likely to nominate women (Goelzhauser 2018a). Survey evidence reveals that attorneys who are women express more interest in seeking judgeships under merit selection while there is no race differential (Jensen and Martinek 2009). Evidence from submitted applications, however, finds no gender differential with respect to expressive ambition and no gender or race differential with respect to progressive ambition (Goelzhauser 2019). Furthermore, the extent to which the design of merit selection systems facilitates commission capture is not associated with diversification (Goelzhauser 2019).

Under elections, survey evidence reveals that attorneys who are women express more interest in running for office while there is no race differential (Williams 2008). Evidence from other institutional contexts suggests that members of historically underrepresented groups exhibit more election aversion (e.g., Kanthak and Woon 2015), receive less elite encouragement to run for office (e.g., Lawless and Fox 2010), and suffer from stereotyped perceptions that discourage entry (e.g., Dolan 2010). Contrary to appointers, though, voters are no less likely to support the selection of women with other women in office (Solberg and Stout n.d.; Bratton and Spill 2002). And there is evidence that once on the bench, members of underrepresented groups do not suffer an electoral penalty (Frederick and Streb 2008; Gill and Eugenis 2019; Hall 2001; Solberg and Stout n.d.). Members of marginalized groups do, however, receive biased performance ratings leading up to retention elections (Gill 2014; Gill, Lazos, and Waters 2011).

Empirical Analysis

Are women of color more likely to be seated under certain judicial selection systems? The empirical analysis proceeds in two steps. First, I provide descriptive information on the first women of color seated on state apex courts. Although the first women of color to serve in the federal judiciary are well known, no systematic information exists about women of color on state courts. As a result, these groundbreaking women have not been collectively recognized, and many of their stories are largely unknown. To recover this history, I gathered information on all state supreme court justices seated from 1960 through 2016 from a variety of sources, including biographies, press releases, and newspaper articles (see Goelzhauser 2016). Second, I analyze the relationship between selection institutions and the seating of women of color on state supreme courts. While emphasizing women of color, the analysis provides comparable results for other gender-race combinations.

The First Women of Color on State Supreme Courts

The history of women of color on the federal bench is comparatively well known. Constance Baker Motley became the first woman of color to hold an Article III judgeship and serve on a district court when she was nominated to the US District Court for the Southern District of New York by President Johnson in 1966—seventeen years after the first woman (Burnita Shelton Matthews) and twenty-nine years after the first person of color (William Henry Hastie Jr., who was also the first person of color to hold an Article III judgeship). Amalya Lyle Kearse was the first woman of color seated on a federal circuit court after being nominated to the US Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit by President Carter in 1979—forty-five years after the first woman (Florence Ellinwood Allen, also the first woman to hold an Article III judgeship) and twenty-nine years after the first person of color (William Henry Hastie Jr.). And Sonia Sotomayor became the first woman of color seated on the US Supreme Court after being nominated by President Obama in 2009—twenty-eight years after the first woman (Sandra Day O’Connor) and forty-two years after the first person of color (Thurgood Marshall). It is notable that in each instance, seating the first woman of color took considerably longer than seating either the first white woman or man of color.

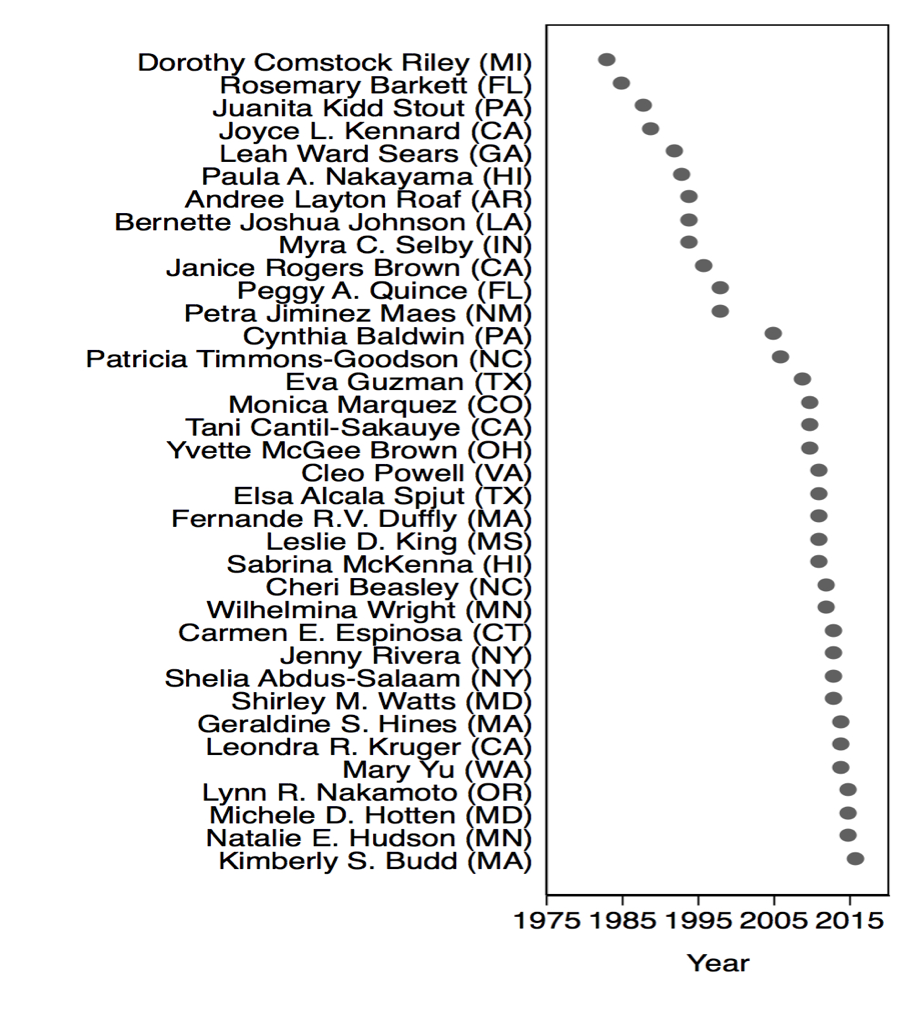

In the states, Dorothy Comstock Riley, who was Hispanic, may have been the first woman of color seated on a state apex court when governor William Milliken appointed her to the Michigan Supreme Court in December 1982. For comparison, Florence Ellinwood Allen, who as noted previously was the first woman to hold an Article III judgeship, was the first woman to serve as a state supreme court justice with her election by Ohio voters in 1922. And Jonathan Jasper Wright, an African American appointed to the South Carolina Supreme Court by the state legislature during Reconstruction in 1870, may have been the first man of color seated on a state apex court. The next Black justice was not seated until Otis M. Smith was appointed to the Michigan Supreme Court in 1961 (see Goelzhauser 2011, 762–763). Thus as with federal firsts, the first woman of color to sit on a state high court did so well after the first white woman and man of color.

Justice Riley spent her career in private practice before serving as a trial and appellate court judge. Riley lost an electoral bid for the Michigan Supreme Court in November 1982, but outgoing Republican governor William Milliken appointed her to an interim position when an incumbent justice named Blair Moody died a few weeks after being reelected. To prevent the incoming Democratic governor James Blanchard from filling the seat, Milliken appointed Riley to serve Moody’s new term even though it had not started. After this maneuver was challenged by the Blanchard administration, the Michigan Supreme Court (with Justice Riley recused) ruled that Justice Riley’s interim appointment was only valid through the end of Blair’s previous term (Attorney General v. Riley 1983). As a result, Riley’s initial tenure lasted from December 9, 1982, through 12:00 p.m. on January 1, 1983. In 1984, however, Riley was elected to the court for a full term and served until 1997, when she resigned due to the onset of Parkinson’s disease.[4] Despite perhaps being the first woman of color seated on a state high court and the only woman of color seated twice during the sample period, her racial identity was seldom mentioned at the time of initial appointment, subsequent election, or death (see, e.g., Associated Press 2004).

Bernette Joshua Johnson was the only other woman of color to be initially seated on a state apex court through election during the sample period. In 1988, the US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit held that Louisiana violated the Voting Rights Act by combining Orleans Parish and its large percentage of Black voters with three predominantly white parishes for the purpose of electing two state supreme court justices while other parishes elected a single justice each; the court found it “particularly significant that no Black person has ever been elected to the Louisiana Supreme Court” (Chisholm v. Edwards 1988, 1058). To remedy Black vote dilution in Orleans Parish, Louisiana entered into a consent decree, deferring redistricting but agreeing to create an intermediate appellate court judgeship for Orleans Parish that would immediately be assigned to the state supreme court, thereby increasing the latter’s size from seven to eight justices (see Perschall v. Louisiana 1997). Johnson, who had been a trial court judge, finished second in a three-way Democratic primary race, which would have resulted in a runoff election except that the white first-round winner withdrew, claiming her presence “threatened to ‘permanently scar’ race relations in New Orleans” amid arguments by Johnson and another Black candidate that the position should be filled by a Black judge in light of the reason for its creation (Orlando Sentinel 1994). After redistricting in 2000, Justice Johnson ran unopposed for reelection to a regular seat, and the court was reduced in size back to seven seats. Johnson was reelected unopposed again in 2010.[5]

Juanita Kidd Stout became the first Black woman to sit on a state’s highest court when governor Robert Patrick Casey Jr. appointed her to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court in 1988. Stout was a music teacher in her home state of Oklahoma before pursuing a career in law after working as a legal stenographer during World War II (Thomas 1998). Stout’s legal experience included private practice and service as an assistant district attorney before receiving an interim appointment to the municipal bench in 1959 (Adams 2015). By retaining her position in a subsequent election, she became the first Black woman elected to any court in the United States (Thomas 1998). After Stout’s 1988 appointment to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, she was forced off the bench in 1989 upon reaching the mandatory retirement age. In 1998, Justice Stout died of leukemia.

Joyce Kennard may have been the first Asian American woman to sit on a state’s apex court when governor George Deukmejian appointed her to the California Supreme Court in 1989. Kennard was born in Indonesia, where her family was detained in a Japanese internment camp before moving to the Netherlands after World War II (Dolan 2014). With English as a third language, Kennard later immigrated to the United States, where after law school she worked as a deputy attorney general and research attorney for a state appellate court. Her judicial career progressed swiftly; she served as a municipal court judge, superior (trial) court judge, and appellate court judge before joining the California Supreme Court (Kort 1993). In 2014, at the age of seventy-two, Justice Kennard retired on the twenty-fifth anniversary of her appointment to California’s high court, declaring, “I’d like to finally make time for my long-neglected friends” (Egelko 2014).

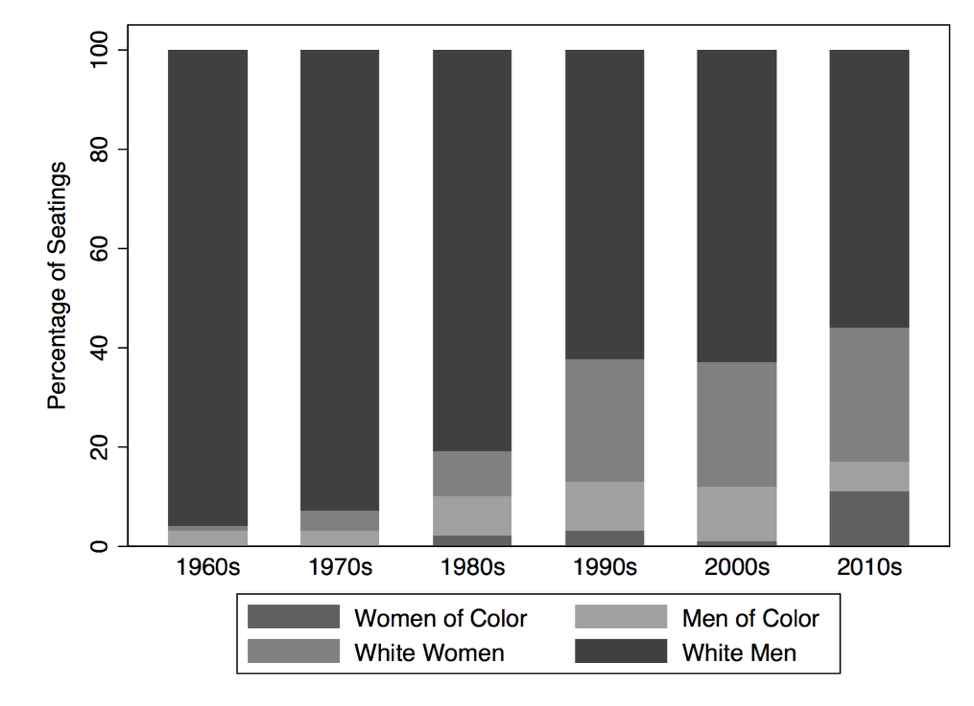

Overall, women of color accounted for 2 percent of state supreme court seatings from 1960 through 2016. During the same period, women and men of color, respectively, accounted for 17 percent and 9 percent of seatings. After 1982, when the first woman of color was seated on a state apex court, 4 percent of the seatings through 2016 were women of color compared to 26 percent and 13 percent for women and men of color, respectively. Figure 1 plots the name and year seated for each woman of color to join a state high court during the sample period. In total, twenty-two states seated women of color on their apex courts during this time. Women of color secured 2 percent of seatings in the 1980s, 3 percent in the 1990s, 1 percent in the 2000s, and 11 percent from 2010 through 2016. For comparison, figure 2 plots the percentage of seats obtained by decade for women of color, men of color, white women, and white men. Of the seatings on state supreme courts involving women of color, 57 percent of the justices were Black, 24 percent were Hispanic or Latina, 16 percent were Asian or Pacific Islander, and 3 percent were Asian and Latina.

Quantitative Analysis

The quantitative analysis employs justice-level data on all new seatings to state supreme courts from 1960 through 2016. The primary dependent variable is scored 1 when a newly seated justice was a woman of color and 0 otherwise. For comparison, I fit separate models for seating men of color, white men, and white women. Combining women from different race and ethnic categories is inconsistent with the overarching emphasis of intersectionality research on treating members of different disadvantaged statuses separately. However, this approach is necessary at this time due to the few women of color to be seated on state high courts. As Scola explained when combining race and ethnic categories in a study of intersectional legislative representation, “While this justification may not be wholly satisfying (for the reader or the author), collapsing the data was necessary to have a sufficient number of cases to test the model” (2013, 341). The key explanatory variables are indicators for whether justices were seated under unilateral elite appointment (gubernatorial or legislative), merit selection, or contestable elections (partisan or nonpartisan).[6] This categorization reflects core institutional similarities but is also driven by the paucity of women of color seated across more finely delineated classifications.[7]

Omitted variable bias occurs when excluding predictors that are correlated with the dependent variable and key explanatory variables. As a result, the models include several control variables that may be associated with state selection system choice and diversification. Previous research indicates that members of underrepresented groups may be more disadvantaged as position value increases. To capture position value, I include an index of state court professionalism (Squire 2008), term length in years, number of court seats, and an indicator for use of a mandatory retirement rule.[8] While each measure captures position value, having shorter terms, more seats, and mandatory retirement may also induce turnover, thereby increasing opportunities for members of disadvantaged groups. Eligibility pool controls account for the number of attorneys in a state who are women or people of color.[9] Since the effect of pool size may be nonlinear, with increases at the low end in the number of attorneys from underrepresented groups mattering more than at the high end, I take the natural log transformation of the raw counts. Given that women of color are generally more likely to secure political office as state liberalism increases (e.g., Scola 2006), I include a dynamic measure of citizen ideology (Berry et al. 1998). Last, because of changes in the likelihood of seating women of color over time, I account for time dependence by including variables counting the number of years since the start of the sample period, the number of years squared, and the number of years cubed (Carter and Signorino 2010).

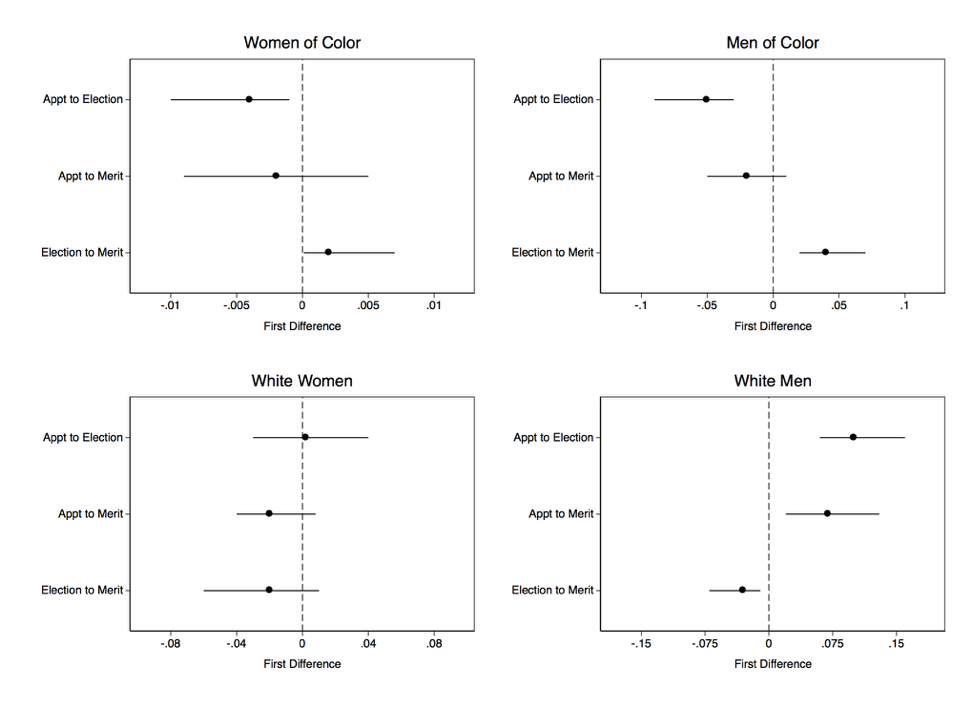

Logistic regression can be used to model binary outcomes, such as whether a woman of color is seated on an apex court. Due to the infrequency of seating women of color, which can bias substantive effects downward, the models are fit using a rare event correction for logistic regression (King and Zeng 2001a, 2001b). Standard errors are clustered by state to account for the fact that observations within a state are not independent, which can lead to incorrect standard errors (Primo, Jacobsmeier, and Milyo 2007). Table 1 in the appendix displays the full results. Table 2 in the appendix displays the results using a multinomial choice model as an alternative estimation strategy. The results are consistent across specifications. Focusing on substantive effects, figure 3 plots first differences for pairwise comparisons of gender and race across selection methods. The effects seem small, but this is often the case with rare event data. To better examine substantive impact with rare event data, King and Zeng suggest examining relative risks, which “are typically considered important in rare event studies if they are at least 10–20 percent” (2001a, 152).

Overall, the results indicate that selection system choice is associated with the likelihood of seating women of color on state supreme courts. As an initial matter, the difference between elite appointment and merit selection is not statistically distinguishable from zero. However, both appointment systems are more likely than elections to produce justices who are women of color. Moving from elite appointment to election is associated with an −88 percent (−97 percent, −40 percent) decrease in the relative risk of seating a woman of color.[10] Moving from election to merit selection is associated with a 316 percent (5 percent, 1,692 percent) increase in the relative risk of seating a woman of color.

Compared to other gender-race combinations, the results for women of color are most similar to those for men of color. The results are more distinct when compared to white men and women, which in turn are distinct from each other. Moving from elite appointment to election is associated with an −82 percent (−92 percent, −65 percent) decrease in the relative risk of seating a man of color. Unlike with women of color, elections are also associated with a change in the likelihood of seating men of color relative to merit selection, with the relative risk increasing by 327 percent (78 percent, 901 percent) moving from the former to the latter. No pairwise selection institution comparison is associated with a statistically significant difference in the likelihood of seating white women. For white men, moving from unilateral elite appointment to election is associated with a 14 percent (7 percent, 22 percent) increase in the relative risk of being seated. Moving from unilateral elite appointment to merit selection is associated with a 9 percent (3 percent, 18 percent) increase in the risk of being seated. While moving from election to merit selection is associated with a −4 percent (−8 percent, 1 percent) decrease, the confidence interval overlaps zero, indicating that we cannot reject the null hypothesis of no relationship.

Pool size and time are the most notable control variables. Increasing the natural log of the number of attorneys of color in a state from its twenty-fifth to seventy-fifth percentile is associated with a 488 percent (55 percent, 1,953 percent) increase in the relative risk of seating a woman of color. However, the same increase in the natural log of the number of attorneys who are women is associated with a −69 percent (−90 percent, −14 percent) decrease in the relative risk of seating a woman of color. The results are similar for men of color. Increasing the natural log of the number of attorneys of color from its twenty-fifth to seventy-fifth percentile is associated with an 860 percent (329 percent, 2,291 percent) increase in the relative risk of seating a man of color. The same increase in the natural log of the number of attorneys who are women, however, is associated with an −82 percent (−92 percent, −61 percent) decrease in the relative risk of seating a man of color. For white women, increasing the natural log of the number of attorneys of color from its twenty-fifth to seventy-fifth percentile is associated with a −34 percent (−50 percent, −11 percent) decrease in the relative risk of being seated. The same increase in the natural log of the number of attorneys who are women is associated with a 47 percent (−1 percent, 109 percent) increase in the relative risk of being seated, though the confidence interval overlaps zero. For white men, increasing the natural log of the number of attorneys of color from its twenty-fifth to seventy-fifth percentile is associated with a −7 percent (−15 percent, 3 percent) decrease in the relative risk of being seated, but this confidence interval also includes zero.

The eligibility pool results have important implications. Consistent with existing research on political institutions and intersectionality, eligibility pools for women and people of color can have disparate effects on representation. Relatedly, there appears to be a tradeoff in seating women and people of color on state apex courts. An increase in the supply of attorneys who are women, for example, decreases the likelihood of seating a person of color. Last, many of the substantive effects are large relative to the effects associated with selection institution choice, suggesting that stakeholders who value diversity should emphasize increasing candidate pools and doing more to encourage and facilitate inclusive access to the bench.

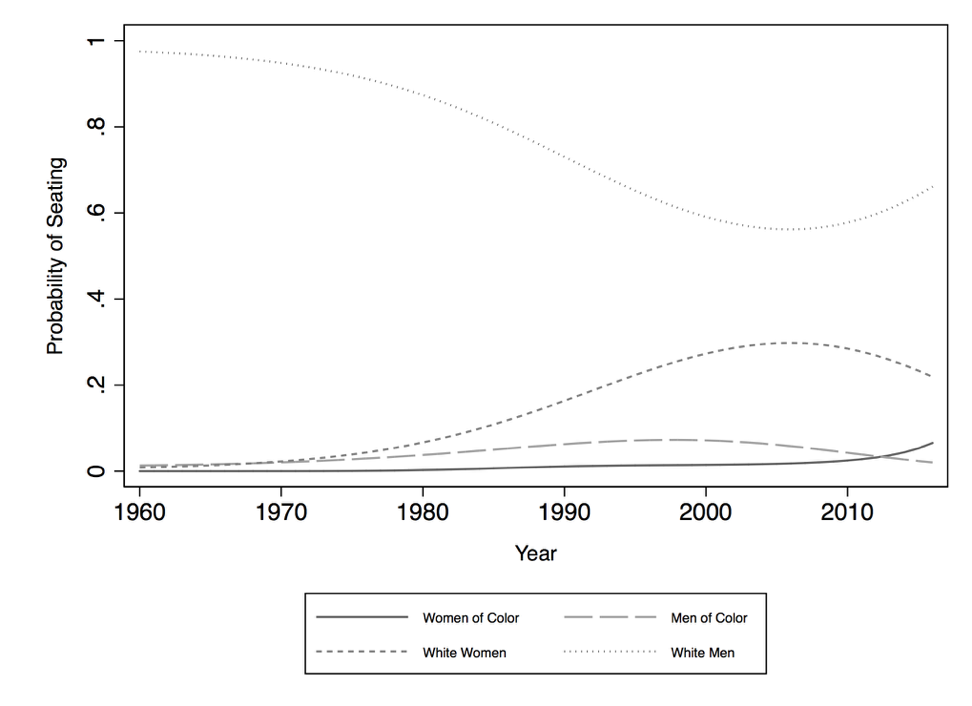

Figure 4 plots the probability of seating justices from various gender-race combinations over time. The probability of seating women of color remains flat and near zero through much of the sample period, with a slight uptick this decade. After remaining relatively flat and near zero through the 1960s, there is a noticeably higher probability of seating men of color and white women beginning in the mid- to late 1970s, corresponding with President Carter’s efforts to diversify the federal judiciary. The uptick for white women, however, is more persistent. In recent years, the probability of seating men of color drops below that of seating women of color. White men held a virtual monopoly in obtaining state supreme court positions at the beginning of the sample period with a declining probability of being seated as members of underrepresented groups joined the bench more regularly. Overall, in the sample period’s later years the probability of being seating is increasing for women of color and white men but decreasing for men of color and white women.

Conclusion

Facing the double disadvantage of gender and race bias, women of color endure discrimination in the legal profession, manifested in part by a lack of representation. This chapter makes two contributions to the existing literature on state court diversity. First, it offers a descriptive account of the women of color who have served on state high courts from 1960 through 2016. While historic federal firsts are widely recognized, this group of groundbreaking women has received comparatively little attention. Second, I examine the relationship between selection mechanism choice and seating women of color. The results indicate that newly seated women of color are less likely to arrive through election than unilateral elite appointment or merit selection. The results are similar for men of color, while newly seated white men are more likely to arrive through election. Selection system choice is not associated with differences in seating white women.

The results have important policy implications. Scholars have amassed a wealth of empirical evidence on the performance of various judicial selection and retention institutions (see, e.g., Bonneau and Cann 2015; Bonneau and Hall 2009, 2017; Cann and Yates 2016; Geyh 2019; Gibson 2012; Goelzhauser 2016, 2019; Hall 2015; Kritzer 2015; Streb 2007). Albeit just one part of the broader debate, the extent to which institutional design choices impact judicial diversification has important consequences for descriptive and substantive representation. With respect to seating women of color in particular, the results presented here suggest that appointment systems outperform elections. While the mechanism is unclear, evidence from a variety of institutional contexts suggests that members of underrepresented groups may be disadvantaged in election systems due to factors such as contest aversion, lack of party support, having fewer political connections, and implicit stakeholder bias. Given increasing evidence that appointment systems tend to outperform elections with respect to diversification, one option for promoting diversity while enjoying the benefits of elections is to increase the use of short-term appointments.

By emphasizing women of color on state supreme courts, this chapter advances our understanding of how marginalized groups secure political representation. But it is important to stress that the broader study of intersectionality is complex, requiring scholars to leverage varied analytical approaches to shed light on the relationship between intersectionality and political action (see, e.g., Cho, Crenshaw, and McCall 2013; Hancock 2013; Holman and Schneider 2018; McCall 2005). These varied approaches are necessary in part because it is important to address other intersections of disadvantage in future research. Discrimination based on marginalized statuses such as religion, sexual orientation, and social class interacts with dimensions such as gender and race in complex ways (see, e.g., Beckwith 2014; Htun and Ossa 2013). One recent study, for example, examined evaluations of political candidates on the basis of gender and sexual orientation (Doan and Haider-Markel 2010). Moving forward, it is imperative to better map this complexity onto theories and empirical tests concerning intersectionality and the study of law and courts.

Learning Activity

Assume the role of a policy maker and consider the following questions:

- What characteristics should judges possess?

- How should we design judicial selection institutions to facilitate the selection of individuals with these characteristics?

- How might these institutional design choices impact diversification and the selection of women of color in particular?

Select a state and research the history of its supreme court diversity. When and how was the first woman, woman of color, and man of color seated?

References

Adams, Brandon. 2015. “African American History Spotlight: Juanita Kidd Stout.” Savanna Herald, April 15.

Alozie, Nicholas O. 1996. “Selection Methods and the Recruitment of Women to State Courts of Last Resort.” Social Science Quarterly 77(1): 110–126.

Alozie, Nicholas O. 1990. “Distribution of Women and Minority Judges: The Effects of Judicial Selection Methods.” Social Science Quarterly 71(2): 315–25.

American Bar Association. 2006. Visible Invisibility: Women of Color in Law Firms.

Aranda, Benjamin. 1996. “Women of Color: The Burdens of Both, the Advantages of Neither.” Judges’ Journal 35(1): 29, 42.

Arrington, Nancy B. 2018. “Gender and Judicial Replacement: The Case of US State Supreme Courts.” Journal of Law and Courts 6(1): 127–154.

Attorney General v. Riley, 332 N.W. 2d 353 (1983). https://law.justia.com/cases/michigan/supreme-court/1983/70876-4.html

Barrett, Edith J. 1995. “The Policy Priorities of African American Women in State Legislatures.” Legislative Studies Quarterly 20(2): 223–47.

Beckwith, Karen. 2014. “Gender, Class, and the Structure of Intersectionality: Working-Class Women and the Pittston Coal Strike.” Politics, Groups, and Identities 2(1): 17–34.

Berry, William D., Evan J. Ringquist, Richard C. Fording, and Russell L. Hanson. 1998. “Measuring Citizen and Government Ideology in the American States.” American Journal of Political Science 42(1): 327–48.

Best, Rachel Kahn, Lauren B. Edelman, Linda Hamilton Krieger, and Scott R. Eliason. 2011. “Multiple Disadvantages: An Empirical Test of Intersectionality Theory in EEO Litigation.” Law & Society Review 45(4): 991–1025.

Blackburne-Rigsby, Anna. 2010. “Black Women Judges: The Historical Journey of Black Women to the Nation’s Highest Courts.” Howard Law Journal 53(3): 645–98.

Bobo, Lawrence, and Franklin D. Gilliam, Jr. 1990. “Race, Sociopolitical Participation, and Black Empowerment.” American Political Science Review 84(2): 377–93.

Bonneau, Chris W., and Damon M. Cann. 2015. Voters’ Verdicts: Citizens, Campaigns, and Institutions in State Supreme Court Elections. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press.

Bonneau, Chris W., and Melinda Gann Hall, eds. 2017. Judicial Elections in the 21st Century. New York, NY: Routledge.

Bonneau, Chris W., and Melinda Gann Hall. 2009. In Defense of Judicial Elections. New York, NY: Routledge.

Bonneau, Chris W., and Heather Marie Rice. 2009. “Impartial Judges? Race, Institutional Context, and U.S. State Supreme Courts.” State Politics & Policy Quarterly 9(4): 381–403.

Boyd, Christina L., Lee Epstein, and Andrew D. Martin. 2010. “Untangling the Causal Effects of Sex on Judging.” American Journal of Political Science 54(2): 389–411.

Bratton, Kathleen A., Kerry L. Haynie, and Beth Reingold. 2006. “Agenda Setting and African American Women in State Legislatures.” Journal of Women, Politics & Policy 28(3–4): 71–96.

Bratton, Kathleen A., and Rorie L. Spill. 2002. “Existing Diversity and Judicial Selection: The Role of the Appointment Method in Establishing Gender Diversity in State Supreme Courts.” Social Science Quarterly 83(2): 504–18. (↵ Return 3)

Broockman, David E. 2014. “Do Female Politicians Empower Women to Voteggenerl or Run for Office? A Regression Discontinuity Approach.” Electoral Studies 34: 190–204.

Brown, Nadia E. 2014. Sisters in the Statehouse: Black Women and Legislative Decision Making. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Burleigh, Nina. 1988. “Black Women Lawyers Coping with Dual Discrimination.” American Bar Association Journal 74(6): 64–8.

Cann, Damon M., and Jeff Yates. 2016. These Estimable Courts: Understanding Public Perceptions of State Judicial Institutions and Legal Policy-Making. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Carter, David B., and Curtis S. Signorino. 2010. “Back to the Future: Modeling Time Dependence in Binary Data.” Political Analysis 18(3): 271–92.

Chisholm v. Edwards, 839 F. 2d 1056 (1988).

Chisholm v. Jindal, 890 F. Supp. 2d 696 (2012).

Cho, Sumi, Kimberle Williams Crenshaw, and Leslie McCall. 2013. “Toward a Field of Intersectionality Studies: Theory, Applications, and Praxis.” Signs 38(4): 785–810.

Collins, Todd A., Tao L. Dumas, and Laura P. Moyer. 2017. “Intersecting Disadvantages: Race, Gender, and Age Discrimination Among Attorneys.” Social Science Quarterly 98(5): 1642–1658.

Collins, Todd, and Laura Moyer. 2008. “Gender, Race, and Intersectionality on the Federal Appellate Bench.” Political Research Quarterly 61(2): 219–27.

Collins, Patricia Hill, and Sirma Bilge. 2016. Intersectionality. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Crenshaw, Kimberle. 1989. “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics.” 1989: University of Chicago Legal Forum 139–67.

Darcy, R., Charles D. Hadley, and Jason F. Kirksey. 1993. “Election Systems and the Representation of Black Women in American State Legislatures.” Women & Politics 13(2): 73–89.

Davis, Sue. 1992. “Do Women Judges Speak `In a Different Voice?’ Carol Gilligan, Feminist Legal Theory, and the Ninth Circuit.” Wisconsin Women’s Law Journal 8(1): 143–74.

DeGraffenreid v. General Motors, 413 F. Supp. 142 (1976). https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/FSupp/413/142/1660699/

Doan, Alesha, and Donald P. Haider-Markel. 2010. “The Role of Intersectional Stereotypes on Evaluations of Gay and Lesbian Political Candidates.” Politics & Gender 6(1): 63–91.

Dolan, Kathleen. 2010. “The Impact of Gender Stereotyped Evaluations on Support for Women Candidates.” Political Behavior 32(1): 69–88.

Dolan, Maura. 2014. “Justice Kennard Retiring from State High Court.” Los Angeles Times, February 11.

Egelko, Bob. 2014. “Joyce Kennard to Retire from California Supreme Court.” San Francisco Chronicle, February 12.

Farhang, Sean, and Gregory Wawro. 2004. “Institutional Dynamics on the U.S. Court of Appeals: Minority Representation Under Panel Decision Making.” Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization 20(2): 299–330.

Frederick, Brian, and Matthew J. Streb. 2008. “Women Running for Judge: The Impact of Sex on Candidate Success in State Intermediate Appellate Court Elections.” Social Science Quarterly 89(4): 937–954.

Fox, Richard L., and Jennifer L. Lawless. 2005. “To Run or Not to Run for Office: Explaining Nascent Political Ambition.” American Journal of Political Science 49(3): 642–59.

Fricke, Amber, and Angela Onwuachi-Willig. 2012. “Do Female ‘Firsts’ Still Matter? Why They Do for Female Judges of Color.” Michigan State Law Review 2012(5): 1529–54.

Gay, Claudine. 2002. “Spirals of Trust? The Effect of Descriptive Representation on the Relationship Between Citizens and Their Government.” American Journal of Political Science 46(4): 717–32.

Geyh, Charles Gardner. 2019. Who is to Judge? The Perennial Debate Over Whether to Elect or Appoint America’s Judges. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Geyh, Charles Gardner. 2003. “Why Judicial Elections Stink.” Ohio State Law Journal 64(1): 43–80.

Gibson, James L. 2012. Electing Judges: The Surprising Effects of Campaigning on Judicial Legitimacy. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Gill, Michael Z., and Andrew B. Hall. 2015. “How Judicial Identity Changes the Text of Legal Rulings.” Working Paper.

Gill, Rebecca D. 2014. “Implicit Bias in Judicial Performance Evaluations: We Must Do Better Than This.” Justice System Journal 35(3): 301–24.

Gill, Rebecca, and Kate Eugenis. 2019. “Do Voters Prefer Women Judges? Deconstructing the Competitive Advantage in State Supreme Court Elections.” State Politics & Policy Quarterly 19(4): 399-427.

Gill, Rebecca D., Sylvia R. Lazos, and Mallory M. Waters. 2011. “Are Judicial Performance Evaluations Fair to Women and Minorities? A Cautionary Tale from Clark County, Nevada.” Law & Society Review 45(3): 731–59.

Goelzhauser, Greg. 2019. Judicial Merit Selection: Institutional Design and Performance in Staffing State Courts. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press. (↵ Return 3)

Goelzhauser, Greg. 2018a. “Does Merit Selection Work? Evidence from Commission and Gubernatorial Choices.” Journal of Law & Courts 6(1): 155–187.

Goelzhauser, Greg. 2018b. “Classifying Judicial Selection Institutions.” State Politics & Policy Quarterly 18(2): 174–192.

Goelzhauser, Greg. 2016. Choosing State Supreme Court Justices: Merit Selection and the Consequences of Institutional Reform. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press

Goelzhauser, Greg. 2011. “Diversifying State Supreme Courts.” Law & Society Review 45(3): 761–81.

Grabham, Emily, Davina Cooper, Jane Krishnadas, and Didi Herman, eds. 2008. Intersectionality and Beyond: The Power and the Politics of Location. New York, NY: Routledge-Cavendish.

Graham, Barbara Luck. 1990. “Do Judicial Selection Systems Matter? A Study of Black Representation on State Courts.” American Politics Quarterly 18(3): 316–36.

Gryski, Gerard S., Eleanor C. Main, and William J. Dixon. 1986. “Models of State High Court Decision Making in Sex Discrimination Cases.” Journal of Politics 48(1): 143–55.

Haire, Susan B., and Laura P. Moyer. 2015. Diversity Matters: Judicial Policy Making in the U.S. Courts of Appeals. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press.

Haire, Susan B., Laura P. Moyer, and Shawn Treier. 2013. “Diversity, Deliberation, and Judicial Opinion Writing.” Journal of Law and Courts 1(2): 303–30.

Hall, Melinda Gann. 2015. Attacking Judges: How Campaign Advertising Influences State Supreme Court Elections. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

Hall, Melinda Gann. 2001. “State Supreme Courts in American Democracy: Probing the Myths of Judicial Reform.” American Political Science Review 95(2): 315–330.

Hancock, Ange-Marie. 2016. Intersectionality: An Intellectual History. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Hancock, Ange-Marie. 2013. “Empirical Intersectionality: A Tale of Two Approaches.” University of California Irvine Law Review 3(2): 259–97.

Hancock, Ange-Marie. 2007. “When Multiplication Doesn’t Equal Quick Addition: Examining Intersectionality as a Research Paradigm.” Perspectives on Politics 5(1): 63–79.

Hardy-Fanta, Carol, Pei-te Lien, Dianne M. Pinderhughes, and Christine Marie Sierra. 2006. “Gender, Race, and Descriptive Representation in the United States: Findings from the Gender and Multicultural Leadership Project.” Journal of Women, Politics & Policy 28(3–4): 7–41.

Holman, Mirya R., and Monica C. Schneider. 2018. “Gender, Race, and Political Ambition: How Intersectionality and Frames Influence Interest in Political Office.” Politics, Groups, and Identities 6(2): 264–280.

Htun, Mala, and Juan Pablo Ossa. 2013. “Political Inclusion of Marginalized Groups: Indigenous Reservations and Gender Parity in Bolivia.” Politics, Groups, and Identities 1(1): 4–25.

Hughes, Melanie M. 2013. “The Intersection of Gender and Minority Status in National Legislatures: The Minority Women Legislative Index.” Legislative Studies Quarterly 38(4): 489–516.

Hughes, Melanie M. 2011. “Intersectionality, Quotas, and Minority Women’s Political Representation Worldwide.” American Political Science Review 105(3): 604–20.

Hurwitz, Mark S., and Drew Noble Lanier. 2017. “Elections and Judicial Diversity.” In Judicial Elections in the 21st Century, eds. Chris W. Bonneau and Melinda Gann Hall. New York, NY: Routledge.

Hurwitz, Mark S., and Drew Noble Lanier. 2008. “Diversity in state and Federal Appellate Courts: Change and Continuity Across 20 Years.” Justice System Journal 29(1): 47–70.

Hurwitz, Mark S., and Drew Noble Lanier. 2003. “Explaining Judicial Diversity: The Differential Ability of Women and Minorities to Attain Seats on State Supreme and Appellate Courts.” State Politics & Policy Quarterly 3(4): 329–52.

Jensen, Jennifer M., and Wendy L. Martinek. 2009. “The Effects of Race and Gender on the Judicial Ambitions of State Trial Court Judges.” Political Research Quarterly 62(2): 379–392.

Kanthak, Kristin, and Jonathan Woon. 2015. “Women Don’t Run? Election Aversion and Candidate Entry.” American Journal of Political Science 59(3): 595–612.

Kastellec, Jonathan P. 2013. “Racial Diversity and Judicial Influence on Appellate Courts.” American Journal of Political Science 57(1): 167–83.

King, Gary, and Langche Zeng. 2001a. “Logistic Regression in Rare Events Data.” Political Analysis 9(2): 137–63.

King, Gary, and Langche Zeng. 2001b. “Explaining Rare Events in International Relations.” International Organization 55(3): 693–715.

Kort, Michele. 1993. “Fairly Unpredictable.” Los Angeles Times, February 7.

Kritzer, Herbert M. 2015. Justices on the Ballot: Continuity and Change in State Supreme Court Elections. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Krivosha, Norman. 1987. “Acquiring Judges by the Merit Selection Method: The Case for Adopting Such a Method.” Southwestern Law Journal 40(6): 15–22.

Lawless, Jennifer L., and Richard L. Fox. 2010. It Still Takes a Candidate: Why Women Don’t Run for Office. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Mansbridge, Jane. 1999. “Should Blacks Represent Blacks and Women Represent Women? A Contingent ‘Yes.’” Journal of Politics 61(3): 628–57.

Martin, Elaine. 1990. “Men and Women on the Bench: Vive law Difference?” Judicature 73(4): 204–208.

Martin, Elaine, and Barry Pyle. 2005. “State High Courts and Divorce: The Impact of Judicial Gender.” University of Toledo Law Review 36(4): 923–48.

Martin, Elaine, and Barry Pyle. 2002. “Gender and Racial Diversification in State Supreme Courts.” Women & Politics 24(2): 35–52.

McCall, Leslie. 2005. “The Complexity of Intersectionality.” Signs 30(3): 1771–1800.

Orlando Sentinel. 1994. “Front-Runner Drops Out of Racially Divisive Runoff.” Orlando Sentinel, October 9.

Oppenheimer, David Bendamin. 2003. “Verdicts Matter: An Empirical Study of California Employment Discrimination and Wrongful Discharge Verdicts Reveals Low Success Rates for Women and Minorities.” University of California Davis Law Review 37(2): 511–566.

Perschall v. Louisiana, 697 So. 2d 240 (1997).

Pozen, David E. 2008. “The Irony of Judicial Elections.” Columbia Law Review 108(2): 265–330.

Primo, David M., Matthew L. Jacobsmeier, and Jeffrey Milyo. 2007. “Estimating the Impact of State Policies and Institutions with Mixed-Level Data.” State Politics & Policy Quarterly 7(4): 446–459.

Reddick, Malia, Michael J. Nelson, and Rachel Paine Caufield. 2009. “Racial and Gender Diversity on State Courts.” Judges Journal 48(3): 28–32.

Reingold, Beth, and Jessica Harrell. 2010. “The Impact of Descriptive Representation on Women’s Political Engagement: Does Party Matter?” Political Research Quarterly 63(2): 280–94.

Scherer, Nancy. 2005. “Blacks on the Bench.” Political Science Quarterly 119(4): 655–75.

Scherer, Nancy, and Brett Curry. 2010. “Does Descriptive Race Representation Enhance Institutional Legitimacy? The Case of the U.S. Courts.” Journal of Politics 72(1): 90–104.

Schneider, Andrew. 2019. “Meet `Black Girl Magic,’ the 19 African-American Women Elected as Judges in Texas.” National Public Radio, January 16.

Scola, Becki. 2013. “Predicting Presence at the Intersections: Assessing the Variation in Women’s Office Holding across the States.” State Politics & Policy Quarterly 13(3): 333–48.

Scola, Becki. 2006. “Women of Color in State Legislatures: Gender, Race, Ethnicity and Legislative Office Holding.” Journal of Women, Politics & Policy 28(3–4): 43–70.

Sisk, Gregory C., Michael Heise, and Andrew P. Morriss. 1998. “Charting the Influences on the Judicial Mind: An Empirical Study of Judicial Reasoning.” New York University Law Review 73(5): 1377–1500.

Smith, Jr., J. Clay. 1997. “Black Women Lawyers: 125 Years at the Bar; 100 Years in the Legal Academy.” Howard Law Journal 40(2): 365–98.

Solberg, Rorie Spill, and Jennifer Segal Diascro. N.d. “A Retrospective on Obama’s Judges: Diversity, Intersectionality, and Symbolic Representation.” Politics, Groups, and Identities (forthcoming).

Solberg, Rorie Spill, and Christopher T. Stout. n.d. “Is Nine Too Much? How the Gender Composition of State Supreme Courts Influences Support for Female Candidates.” Working Paper, Oregon State University.

Songer, Donald R., Sue Davis, and Susan Haire. 1994. “A Reappraisal of Diversification in the Federal Courts: Gender Effects in the Courts of Appeals.” Journal of Politics 56(2): 425–39.

Squire, Peverill. 2008. “Measuring the Professionalization of U.S. State Courts of Last Resort.” State Politics & Policy Quarterly 8(3): 223–38.

Stokes-Brown, Atiya Kai, and Kathleen Dolan. 2010. “Race, Gender, and Symbolic Representation: African American Female Candidates as Mobilizing Agents.” Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties 20(4): 473–94.

Streb, Matthew J., ed. 2007. Running for Judge: The Rising Political, Financial, and Legal Stakes of Judicial Elections. New York, NY: New York University Press.

Szmer, John, Robert K. Christensen, and Erin B. Kaheny. 2015. “Gender, Race, and Dissensus on State Supreme Courts.” Social Science Quarterly 96(2): 553–75.

The Associated Press. 2004. “Obituaries in the News: Dorothy Comstock Riley.” AP Online, October 25.

Thomas, Robert, Jr. 1998. “J.K. Stout, Pioneering Judge in Pennsylvania, Is Dead at 79.” New York Times, August 24.

Weaver, Velsa M. 2012. “The Electoral Consequences of Skin Color: The ‘Hidden’ Side of Race in Politics.” Political Behavior 34(1): 159–192.

Welch, Susan, Michael Combs, and John Gruhl. 1988. “Do Black Judges Make a Difference?” American Journal of Political Science 32(1): 126–36.

Williams, Margaret S. 2008. “Ambition, Gender, and the Judiciary.” Political Research Quarterly 61(1): 68–78.

Wolak, Jennifer. 2015. “Candidate Gender and the Political Engagement of Women and Men.” American Politics Research 43(5): 872–96.

Further Reading

Attorney General v. Riley, 332 N.W. 2d 353 (1983). https://law.justia.com/cases/michigan/supreme-court/1983/70876-4.html

Chisholm v. Edwards, 839 F. 2d 1056 (1988).

Chisholm v. Jindal, 890 F. Supp. 2d 696 (2012).

Perschall v. Louisiana, 697 So. 2d 240 (1997).

Appendix: Tables

| Women of Color | Men of Color | White Women | White Men | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Election | -2.045***

(0.737) |

-1.805***

(0.390) |

0.024

(0.194) |

0.801***

(0.170) |

| Merit Selection | -0.601

(0.380) |

-0.332

(0.271) |

-0.255

(0.169) |

0.501***

(0.172) |

| Court Professionalism | 1.970

(1.280) |

1.094

(1.017) |

0.002

(0.586) |

-0.613

(0.669) |

| Seats | 0.100

(0.195) |

0.023

(0.156) |

0.018

(0.071) |

-0.018

(0.074) |

| Term Years | 0.031

(0.031) |

-0.055*

(0.032) |

-0.007

(0.013) |

0.023*

(0.014) |

| Mandatory Retirement | 0.671*

(0.382) |

0.114

(0.248) |

0.130

(0.145) |

-0.156

(0.173) |

| In(Lawyers: Women) | -0.618**

(0.296) |

-0.933***

(0.222) |

0.221***

(0.110) |

0.105

(0.126) |

| In(Lawyers: People of Color) | 0.669*** | 0.914*** | -0.168*** | -0.167* |

| Citizen Liberalism | 0.015

(0.014) |

0.028**

(0.014) |

0.004

(0.005) |

-0.014**

(0.006) |

| Time | 0.807**

(0.398) |

0.013

(0.073) |

0.069

(0.112) |

-0.045

(0.062) |

| Time2 | -0.020*

(0.011) |

0.003

(0.003) |

0.002

(0.003) |

-0.003

(0.002) |

| Time3 | <0.001**

(<0.000) (4.788) |

<-0.001

(<0.001) (1.675) |

<-0.001

(<0.001) (1.206) |

<-0.001

(<0.001) (1.197) |

| Observations | 1,609 | 1,609 | 1,609 | 1,609 |

*** p<.01, ** p<.05, ** p<.10. Standard errors clustered by state are in parentheses. Unilateral elite appointment is the excluded selection system baseline.

| Men of Color | White Women | White Men | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Election | 1.772

(1.493) |

10.149***

(7.112) |

13.069***

(10.060) |

| Merit Selection | 1.419

(0.520) |

1.549

(0.650) |

2.281**

(0.916) |

| Court Professionalism | 0.356

(0.330) |

0.123

(0.186) |

0.100

(0.149) |

| Seats | 0.920

(0.170) |

0.912

(0.185) |

0.895

(0.191) |

| Term Years | 0.922***

(0.026) |

0.968

(0.031) |

0.982

(0.033) |

| Mandatory Retirement | 0.516*

(0.178) |

0.495*

(0.206) |

0.423**

(0.174) |

| In(Lawyers: Women) | 0.811

(0.288) |

2.441***

(0.745) |

2.087**

(0.663) |

| In(Lawyers: People of Color) | 1.141

(0.327) |

0.407***

(0.102) |

0.444***

0.119 |

| Citizen Liberalism | 1.010

(0.013) |

0.986

(0.016) |

0.979

(0.015) |

| Time | 0.351***

(0.142) |

0.381***

(0.153) |

0.351***

(0.141) |

| Time2 | 1.029***

(0.011) |

1.027**

(1.011) |

1.025**

(0.011) |

| Time3 | 1.000***

(<0.001) |

1.000***

(<0.001) |

1.000***

(<0.001) |

| Observations | 1,609 | 1,609 | 1,609 |

***p<.01, ** p<.05, ** p<.10. The results display relative risk ratios. Standards errors clustered by state are in parentheses. Unilateral elite appointment is the excluded selection system baseline. Women of color is the excluded reference category.

- For broader discussions of intersectionality and politics, see Collins and Bilge (2016), Grabham et al. (2008), and Hancock (2016). ↵

- Although much of the literature on the effects of descriptive representation focuses on the presence of either women or people of color, studies exploring the consequences of intersectional representation are increasing (see, e.g., Stokes-Brown and Dolan 2010). ↵

- Studies of intersectional legislative representation are more prominent (see, e.g., Barrett 1995; Bratton, Haynie, and Reingold 2006; Brown 2014; Darcy, Hadley, and Kirksey 1993; Hardy-Fanta et al. 2006; Hughes 2011, 2013; Scola 2006, 2013). ↵

- For biographical details from the Michigan Supreme Court Historical Society, see http://www.micourthistory.org/justices/dorothy-riley/. ↵

- For additional details on the aftermath of the consent decree, see Chisom v. Jindal (2012). There is some dispute concerning whether Justice Johnson was first elected to the Louisiana Supreme Court in 1994 or 2000 given that the initial position was a specially created intermediate appellate court seat assigned to the state supreme court. This question resulted in litigation when a disagreement arose as to who was next in line by seniority to become chief justice, Johnson or an individual who was first elected in 1995. In creating the redistricted position Johnson secured in 2000, Louisiana law stipulated that “any tenure on the supreme court gained by [the judge elected to fill this position] while so assigned to the supreme court shall be credited to such judge” (706). Referencing this provision and parts of the consent decree stating that the position would effectively be equivalent to a supreme court seat, a federal district court held that Justice Johnson’s time on the state supreme court began in 1994, and she ultimately became chief justice in the disputed contest. As a result of these factors, I classify Justice Johnson as being first seated in 1994. ↵

- It is notable that women of color are regularly seated through interim appointments. Of the twenty-six women of color appointed to state supreme courts during the sample period, fifteen (58 percent) received interim appointments. ↵

- Measurement of the key explanatory variables is straightforward with the exception of merit selection (see Goelzhauser 2018b). States are classified as employing merit selection if they have a statute or constitutional provision mandating that a commission winnow applications and nominate a short list of individuals from which the governor makes an appointment. ↵

- The term length variable takes a value of thirty in state years with no applicable terms. ↵

- The attorneys of color variable combines census information on the number of Black and Hispanic attorneys in a state. Census data are not as extensive with respect to the number of Asian American attorneys by state. ↵

- All quantities of interest are calculated by setting mandatory retirement to its mode (yes) and other variables to their means. Parentheses include 95 percent confidence intervals. ↵