Chapter 5: Create the Estate Plan

Now that we have organized the business and set it up for an orderly succession process to let Gen 2 retire and Gen 3 take over management, we can show how Gen 2 can use this structure to create an estate plan that protects their legacy, where the farm business is viable and their family is content with the distribution of their assets after death.

To ensure that the family farm will survive and thrive into the future, it is important that the Gen 3 farm manager gets full control of the operating entity before or after Gen 2’s passing. Furthermore, it is likely that there are Gen 3 children who are not interested in farming but still want their fair share of Gen 2’s estate. We have already discussed how LLCs can be used to give ownership interests in the business without giving away management control, but some nonfarming Gen 3s might not have an interest in being part of the farm ownership. They may prefer to have other assets—family heirlooms, a vacation home, or simply cash from the estate. While all parents want to treat their children fairly, it is not essential to give each of them exactly the same thing, such as a piece of farmland, or the same value of assets, especially if some of those assets are essential for the business. In order to keep the farm operating and the family together, we tell families that fairness is really about giving each child something meaningful and helpful for their lives. We know that our children can be completely different from one another in every way, and our gifts to them can be different too as long as everyone feels taken care of and understands the reason for the plan that is created. Communication is key to understand expectations, strive to meet expectations, and explain if the plan is not exactly what was expected at first.

Given the business organization and succession plan described earlier, here is how the distribution portion of the will or trust would work: Assume there are three Gen 3 children, and one of the children wants to farm. Also assume that the rest of the children do not want to farm, and they want to live somewhere away from the farm. This example does not address the issues related to a nonfamilial farming successor, sometimes referred to as a nonfamilial Gen 3. That will be discussed separately. The will or trust with a family Gen 3 would direct that upon the death of the last living Gen 2,

- any remaining membership interests in Hobson Farms LLC will be distributed to the on-farm Gen 3, and

- any remaining membership interests in Hobson Cropland LLC will be distributed in equal shares to all the children and farm and nonfarm Gen 3s.

Keep in mind that following the death of both Mom and Dad, all the leases and any management agreement for land or livestock remain in effect. When the Farm Gen 3 receives all the ownership interests in Hobson Farms LLC, Farm Gen 3 will have full ownership and management control of the operating entity. Gen 3 does all the work and assumes all the risk but also reaps the reward. The rest of the children inherit a very valuable asset to be shared equally between them in the form of Hobson Cropland LLC. Hobson Cropland LLC should be designed to operate in a very business-like manner. It should give all the children a way to deal with one another. Done well, everyone should be able to sleep at night without worrying that someone is taking advantage of someone else. It should be structured in a way that allows all the children to get a reasonable rate of return on their inherited investment. It should include provisions allowing a member to withdraw in such a way that it will do no harm to the farming operation while paying the departing member for the fair value of their membership interest (according to the operating agreement). It should include provisions protecting the members from the mishaps and mistakes that can happen in life.

If Mom and Dad are concerned about the fairness of this plan, the trust or will can give family heirlooms, vacation property, personal vehicles, cash, life insurance proceeds, or other investment accounts to certain children. It is important to note that the on-farm Gen 3, who may have spent decades on the farm already before Mom and Dad died, has worked for their shares in the business as well, depending on the plans set up for transferring ownership interests in the LLCs over time. Likewise, the other children have been working in their respective professions in that time and have built up their own livelihoods. Fairness and consideration for each person’s circumstances is important for family well-being, but it is also critically important that the farm pass on to the next generation in such a way that it can continue to support the family and contribute to society’s need for food and fiber. Talking about the succession plans and being open and honest in sharing Gen 2’s goals and wishes with the family can help ease concerns before the grief of the parent’s passing is added to the stress of distributing the estate.

If you have a nonfamily Gen 3, they should not be a part of the estate plan. The estate plan is for the family. Your nonfamily Gen 3 should be allowed to buy into an ownership position in Hobson Farms with cash contributions to capital. Closely track the cash contributions so that everyone understands that the nonfamily Gen 3 is not taking any assets that the family Gen 3 feels belong to them. When the last living member of Gen 2 dies, the nonfamily Gen 3 should have the opportunity to buy the rest of the shares in Hobson Farms LLC so that they have full ownership of the operating entity. If the farm is profitable and has a reasonable rate of return, it should be a valuable investment for the nonfamily Gen 3. If the nonfamily Gen 3 wants to withdraw, they will be paid for their ownership interests in Hobson Farms LLC (which they paid for with cash) with simple interest from the date of the purchase. If the nonfamily Gen 3 was also able to buy land or build a herd or develop other valuable business assets as part of the relationship, they still have full ownership and can go on their way. As we have structured it, the farm could continue to operate with a new hired manager, or it could be sold. The family Gen 3 children would still have ownership interests in the land LLC, so they have a valuable asset that they can sell or rent into the future. Everyone can be taken care of if the arrangement doesn’t work out between these particular individuals.

To achieve those goals in estate planning, wills and trusts will be used as the primary tools. We will also consider liquidity and other forms of wealth owned by Gen 1 and 2 along with the estate and capital gains taxes that come into play in order to preserve the greatest amount of the value of the estate that will go to the farm and family members.

A. Wills

When you die, all assets in your name legally go to your heirs. Your heirs will conduct a probate, which is a specialized court proceeding and the only legitimate way to determine who your heirs are and which heirs get what. If you have prepared a legitimate will before you died, that probate will follow its terms. If you have not prepared a legitimate will, then the probate court will create one for you based on a state statute. While the state statute is designed to give your family members your assets after your death in an orderly way (spouse and children, then to more distant family if you have no living spouse or children at the time of your death), it might not be exactly as you or your heirs would wish. Creating a valid will is the best way for everyone to assure that your assets are distributed exactly as you desire.

There are ways to avoid having to go through probate to transfer assets to your heirs. One is to own property with rights of survivorship, where two or more people own the same asset and their ownership is set up so that if one of them dies, the title to the asset goes automatically to the surviving owner. In Oregon, owning land as joint tenants (any two or more people) or as tenants by the entirety (married couples) includes rights of survivorship if the joint ownership is established at the time when you take ownership of the property and both parties have equal interests. Another way to avoid probate is to create a “transfer-on-death” form of ownership. For instance, Oregon now recognizes what is called a transfer-on-death deed, which will allow a person to set up ownership in a parcel of land so that the title transfers to another named person upon the first party’s death without giving that person ownership of the land until after the death of the first owner. In addition, most life insurance, annuity policies, and bank and investment accounts give a person the alternative of designating a beneficiary or providing for transfer on death. A better way to try to avoid probate is through the use of a trust.

Even if you have set up ownership of your assets to avoid probate using survivorship rights, transfer on death, or beneficiaries, everyone needs to have at least a basic will just in case something was missed. Always get guidance from competent professional advisors. For example, there are many potential traps, pitfalls, and dangers involved in setting up joint ownership. It can easily backfire, and what seemed like an easy solution can become a big nightmare. It is essential to get good advice before doing any of the things mentioned here.

B. Trusts

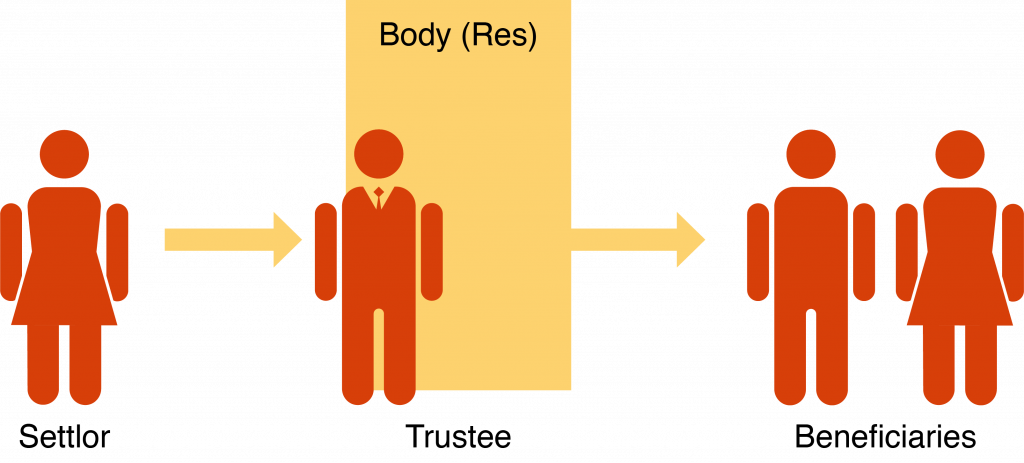

A trust can be used as an alternative or supplement to a will. A trust is an agreement between the one who is creating the trust (called the settlor in Oregon) and a trustee. To create the trust, the settlor drafts the trust agreement and transfers assets (the body or res) to the trustee. The trustee holds title to those assets and follows the trust agreement. The trustee holds the title to those assets for the benefit of a third party, called a beneficiary, who you will designate in the trust (figure 15). If some of the trust assets must be spent for the benefit of the beneficiaries, the trustee has the power to spend those assets after ensuring that they meet the conditions in the trust.

Under modern law, you can create what is called a “joint revocable trust.” That is where a couple creates a trust under which they are the settlors, the trustees, and the beneficiaries all at the same time. They typically convey the title to all their assets to the trust, such that they own nothing in their own individual names. As the beneficiary, they provide that during their lifetimes, the trust assets are there to take care of them. They provide that if they become incapacitated, then a family member or professional will become the successor trustee to manage their assets for their care. Typically, upon the death of the last living spouse, the trustee follows the terms of the trust agreement, pays off any bills, and distributes the remaining assets to the designated beneficiaries, all according to and following the Oregon laws regarding trust administration. Done correctly, they can avoid going through probate, because when they die, there is nothing in their individual names. All the assets are in the trust. In the end, a trust can have the same general effect as a will, but it has the benefit of avoiding probate proceedings.

C. Tax Planning

While we can’t always make taxes go away, we can use some strategies to help families manage them. Remember that we are doing the business succession and estate planning at the same time because some choices can be helpful for both, and we want to make sure that both plans work together. Here we will assume that Gen 2 is a couple, Mom and Dad, who start the process with Dad owning everything in his own name as a sole proprietorship. We discussed the benefits of creating one or more LLCs and moving the business assets into the LLC. For the sake of our example, let’s assume that Dad owns the shares in the LLC. While that is a good step and helps a bit, the full value of the business would still be owned by Dad. Now we can show how distributing business ownership and other personal assets to other family members during Dad’s life, as we have previously discussed with LLC ownership interests for business succession purposes, can also help to manage estate taxes.

Estate taxes are an enormous hurdle facing a successful transfer of a family farming operation on to the next generation—particularly in Oregon. When a farmer dies without any business succession or estate planning in place, the high value of farm businesses makes them vulnerable to Oregon’s estate tax laws. Estate tax liability forces Oregon farmers to make difficult decisions to keep the family farming operation together when a death occurs.

1. Estate Taxes

Estate taxes are based on the value of the assets of the deceased person at the time of their death, after all debts of the estate have been paid. If the value of the estate assets is less than the exclusion limit set in the law, then no estate taxes will be due. Therefore, estate tax planning involves understanding the value of the assets owned by someone when they die and finding ways to reduce the value of the estate so that it will be below the exclusion limit. If the value of the estate exceeds the exclusion limit at the time of death, then estate tax will be due.

After a quick review of current federal and Oregon capital gains and estate tax law, we will look at the strategies available to reduce the taxable estate so that it falls below the exclusion limit. This can be a challenge for farm businesses, primarily because the value of farmland is so high—farmers tend to be land rich and cash poor, making high taxes owed on a short timeline challenging for the business. However, there are steps to take before death that can be used to minimize or eliminate estate taxes.

Capital gains tax. Capital gains tax is assessed on the difference between the sale price of an asset, like farmland, and its original purchase price (table 4). Long-term capital gains tax rates apply to assets held for more than a year, which would be typical for farm assets. The exact tax rate depends on your tax bracket. For assets held for one year or less, short-term capital gains are taxed as ordinary income. If the farm is sold outright to a new operator, capital gains tax applies and is likely to be higher than taxes due with a succession process and proper estate tax planning, as described later (tables 4–7).

|

Current Value of Hobson Cropland, LLC |

$1,000,000 |

|

Tax Basis = Gen 2 Original Purchase Price |

$100,000 |

|

Capital Gain on Sale to Gen 3 |

$900,000 |

|

Estimated Federal and Oregon Capital Gains Tax * |

$265,000 |

|

*Assuming median Oregon income, asset held over 1 year. |

|

Federal estate tax. As of 2019, the federal estate tax does not apply until the net taxable estate rises above $11.4 million for individuals and $22.8 million for couples. The estate tax exclusion will rise with inflation each year until 2025, when it reverts back to a $5 million exclusion (adjusted for inflation) if Congress does not pass a law keeping the higher exemptions in place. There is a 40 percent federal tax for estates exceeding the exclusion amount. It is not unusual for an Oregon family farming operation to be valued at $10 million for estate tax purposes, so most farms should have a tax plan that is flexible and should adjust it based on the current federal estate tax law. It is important to be in touch with a tax planner to keep on top of changes in the exclusion limit.

Oregon estate tax. Oregon’s estate tax law is independent of the federal estate tax laws. As of 2019, Oregon’s estate tax law only excludes the first $1 million of the taxable estate, which is a problem for Oregon farms and ranches. The Oregon estate tax rate for the first $500,000 over the exemption starts at 10 percent and rises to a maximum of $1,022,500 plus 16 percent for an estate valued over $9.5 million. Oregon also has the Oregon Natural Resources Credit that may be available if certain criteria are met (see the following section). You should always consult with a tax attorney to keep up with changes and adjust your estate plans accordingly. The Oregon estate tax is often the largest estate tax issue that we need to worry about for Oregon farms.

2. Estate Tax Planning Strategies

Division on the first death. While we are assuming today’s conventional arrangement in which Dad owns all the business assets through the LLCs, Mom is still in the picture and can be a joint owner of those assets or hold some in her own name. If the entire estate exceeds Oregon’s $1 million exclusion or the federal estate tax exemption, we can divide the estate into two so that only half of the total value is subject to estate tax when the first parent dies. This strategy is called division on the first death.

The practical effect of this strategy is to double the estate tax exemption. In Oregon, that means that $2 million is exempt from taxes rather than $1 million. The half that is attributed to Dad is valued as his estate when he dies, with the first $1 million excluded. The half that is attributed to Mom is valued as her estate when she dies, with her first $1 million excluded. The difficulty is that we have to maintain a firewall between Mom’s and Dad’s halves to maintain the tax status, which changes and complicates the way that they manage their money. However, it can result in significant tax savings. A tax attorney and accountant are critical if you have a high-value estate in Oregon.

Gifting and federal gift tax. If your asset value is higher than the exemptions, even after considering division on the first death, you can move assets out of your estate by giving them away during your lifetime. Once you transfer ownership of your assets—be it possessions, LLC membership interests, or cash—they are no longer yours and do not count toward your taxable estate. There is one big caveat to gifting: do not give away anything that you do not want to leave the family due to death, divorce, or debt. Once you give something away, you give up all control over it, with a few exceptions if you make a plan. For example, if your LLC interests have buy-sell agreements to keep them in the family, you can give them away with more confidence that the business will stay in the family. However, if you simply give away a piece of land, heirloom, or cash to your child, your child has the freedom to sell it, their creditors can get access to it, or they may lose it in a divorce settlement. Most things of value that you give away are out of your control when you transfer ownership, and you cannot predict what the future holds for the person that you give it to, so choose carefully.

The other caveat is the federal gift tax. In 2019, each person can give away up to $15,000 every calendar year to each person that you are giving gifts to, with the amount indexed to inflation. Therefore, Mom and Dad can give a combined total of $30,000 to each child or grandchild each calendar year, tax-free. If the gift in a calendar year goes above that amount, you have to file a gift tax return. No tax has to be paid with that return, but it reduces the amount you can pass free of federal estate tax.

Capital gains tax consequences are also possible if a person receives a gift of appreciated and/or appreciating property, like farmland. If a parent gives a child a gift of farmland while they are alive, the child also receives the parent’s tax basis for figuring capital gain tax if the property is ever sold. Tax basis is what the parent bought the land for, which means that the child will pay capital gains tax on the increase in value between when the land was bought and when it was sold—a large amount in today’s markets (table 5).

|

Current Value of Hobson Cropland, LLC |

$1,000,000 |

|

Gift to Gen 3 Tax Basis = Gen 2 Original Purchase Price |

$100,000 |

|

Capital Gain on Gen 3 Sale to Third Party |

$900,000 |

|

Estimated Federal and Oregon Capital Gains Tax * |

$265,000 |

|

*Assuming median Oregon income, asset held over 1 year. |

|

On the other hand, if the child receives the same land as an inheritance, the child also gets a “step up in basis” to the value of the property on the parent’s date of death, a huge benefit given the value of farmland today that likely outweighs the estate tax that would be paid if the parent kept it until death (table 6). Careful calculations and good advice from one’s lawyer and accountant are very important to have when you are considering your alternatives here. In addition, forming a landholding LLC would also help to avoid those complications, as interest in the landholding LLC can be given over time and, as discussed next, can benefit from minority discounting.

|

Current Value of Hobson Cropland, LLC |

$1,000,000 |

|

“Step up” Tax Basis = Value at time of inheritance |

$1,000,000 |

|

Value of Other Estate Assets |

$600,000 |

|

Total Taxable Estate |

$1,600,000 |

|

Estimated Oregon Estate Tax * |

$60,250 |

|

*Note that the value of the taxable estate would have to be quite high to generate an estate tax higher than the capital gains tax resulting from the sale or gift to Gen 3 before Gen 2’s death, as illustrated in Tables 3 and 4. |

|

Minority discount. Putting land into a landholding LLC allows us to take advantage of the minority discount when valuing a person’s estate at death. We can use the example of Hobson Cropland LLC from chapter 4. Assume that at their death, Mom and Dad own most of Hobson Cropland LLC, having only given away a small portion during their lives. The value of the LLC interests given to the child is the appraised value of the land times the percentage interest the parent owned at the time of death. If the land is worth $1 million and the parents own a 75 percent interest in Hobson Cropland LLC, the value attributed to their estate is $750,000 just from that LLC. That amount will be added to the calculation of the taxable estate to determine whether any estate taxes are owed and how much (see example, table 7).

|

Current Value of Hobson Cropland, LLC |

$1,000,000 |

|

“Step up” Tax Basis in 75% of the LLC Value owned by Gen 2 |

$750,000 |

|

Value of Other Estate Assets |

$600,000 |

|

Total Taxable Estate |

$1,350,000 |

|

Estimated Oregon Estate Tax |

$35,000 |

However, assume that during their lifetime, the parents were able to give away most of the membership interests in Hobson Cropland LLC, and they only own a 45 percent interest at the time of death. Most appraisers would conclude that the value of a 45 percent interest is not equal to 45 percent of the appraised value of the LLC. Instead, that minority interest can be discounted substantially because a person on the street would not pay full value for it in a closely held family LLC (see example, table 8). There are a lot of trade-offs in using this technique, including that it might prevent the family from using the Oregon Natural Resources Credit described later, so it should only be considered along with advice from your lawyer and accountant. Also, the technique is currently under attack by the IRS, which is promulgating some new rules that would limit or eliminate the technique going forward.

|

Current Value of Hobson Cropland, LLC |

$1,000,000 |

|

“Step up” Tax Basis in 45% of the LLC Value owned by Gen 2 with 30% Minority Discount |

$315,000 |

|

Value of Other Estate Assets |

$600,000 |

|

Total Taxable Estate |

$915,000 |

|

Estimated Oregon Estate Tax (under $1 million) |

$0 |

Federal generation-skipping tax. Under the federal estate tax system, the estate tax is imposed on the value of the entire taxable estate regardless of who receives it. A generation-skipping tax is imposed on the value of bequests that go to certain transferees who are referred to as “skip persons.” Individuals who are two or more generations below the deceased person, such as a grandchild, are a large category of skip persons. The purpose is to make sure that estate taxes are not avoided by continually moving wealth down two generations. If the grandparents gave the money to their children, the children would be taxed on the wealth at their death. If the grandchildren get the wealth, then taxes would not be imposed on that wealth until the grandchildren die.

At this time, the exemption from the generation-skipping tax is the same as the exemption from federal estate taxes, which means that grandparents could move a significant amount of money—up to $22.8 million for a couple—without incurring the generation-skipping tax. Most Oregon farms will not have to worry about this tax and can leave bequests to grandchildren or in trust to grandchildren without penalty.

Federal special-use valuation. The farmland is the asset with the highest value, so anything to reduce the taxable value of the land is helpful. For federal estate tax purposes, the special-use valuation reduces the value of the estate, allowing some property to be valued for its actual use rather than for its “highest and best use” (as determined by a standard appraisal) for estate tax purposes, such as the value if it were developed into residential or commercial use. However, in Oregon, the development value is essentially the same as the farm value in most circumstances because the state’s land-use laws restrict the development of farmland. The farm value is the value of the farm for estate tax purposes in Oregon.

Transferring assets like land into an LLC does not take those assets out of your estate for valuation and calculation of estate taxes. There are several ways to deal with the value of the land in your estate tax planning, such as the following:

- utilizing the Oregon Natural Resources Credit

- gifting some land LLC ownership interests to other family members

- discounting minority interest

- planning to have cash available to pay any estate taxes due so that land does not have to be sold

Conservation easements. One way to generate some cash for the farm business is to sell a conservation easement or working lands easement to a nonprofit land trust or a state or local agency. These transactions also reduce the land’s appraised value (although they do not always reduce its actual sales price), because the easement restricts the use of the land in the present and future, even for future owners. The land has a lower market value because any future owner has to abide by the terms of the conservation easement. Of course, the cash value of the easement goes into the business and estate, so depending on the timing of its sale and the death of the land and business owner, that value may still be part of the estate.

Donations to charity can also be deducted from federal estate tax in the same way that charitable donations are deductions from income tax. If a conservation easement is donated instead of sold, then the value is deducted from the taxable estate according to specific IRS rules about the type of easement and value of the land. If the easement is given during life, it qualifies for an income tax deduction that can be carried forward for up to fifteen years for qualifying farmers. If the easement is donated by will or by the heirs when settling the estate, it qualifies for the estate tax deduction. When considering conservation easements, it is best to consult with your accountant, tax planner, and attorney about the type, amount, and timing of entering the easement and whether it should be sold or donated.

Oregon Natural Resources Credit. Oregon estates valued at less than $15 million can use the Oregon Natural Resources Credit (ONRC). It operates as an estate tax credit. After calculating the federal and Oregon estate taxes, you can determine whether you can take the ONRC by identifying the “natural resource assets” in the estate, such as land and livestock. The natural resource property must also be farmed by family before and after death to qualify. You then determine the ratio between the value of the natural resource assets (the numerator) and the adjusted gross estate (the denominator). If the natural resource assets are less than 50 percent of the adjusted gross estate, the credit is not available to that estate. In other words, Gen 2 must have more than 50 percent of their assets as natural resource property in their estate to use the ONRC (figure 16).

If the credit is available, then you calculate the credit by multiplying the amount of Oregon estate tax that would be due from the estate by the percentage of the estate that consists of natural resource assets represent. If 60 percent of the value of the estate comes from natural resources property, then the estate tax bill is reduced by 60 percent.

If you want to use the Oregon Natural Resources Credit (ONRC) to reduce estate taxes, at least half of your estate’s value must come from natural resources assets such as the farmland. If you are gifting ownership of the LLC that owns the land while you are alive, be sure to keep enough of it in your estate so that you can use the ONRC. An accountant and tax attorney can help you with this planning

Another important consideration here is the effect of a gifting plan on the ONRC. The ONRC is only available if the estate consists mostly of natural resource assets. If you want to be able to take advantage of the ONRC on your death, you don’t want to give away so much of Hobson Cropland LLC that the value of your remaining interest in the LLC is less than your assets that are not natural resources. If you want to take advantage of the ONRC, you may want to concentrate on giving away other assets, such as investment accounts or interests in the operating entity, Hobson Farms LLC, so that the majority of your taxable estate comes from land or other natural resource property.

D. Liquidity

For most farms and ranches, the vast amount of the value of the estate is tied up in the business assets. We need to keep in mind that transferring assets like land into an LLC does not take those assets out of one’s estate for purposes of valuing the estate and calculation of estate taxes. Upon setting up and funding an LLC, the value of the land is now in the LLC, but at the same time, the corresponding value of the LLC membership interest is now in the estate to replace the land. Therefore, the value of the estate stays the same both before and after the creation of the LLC (there is a possibility of “discounting” LLC membership interests, but you need advice from an account and tax expert when determining discounts for LLC ownership interests; see chapter 5). As you sell or gift LLC interests to the next generation, you also reduce the value of the taxable estate. While there can be estate tax benefits to organizing the farm as an LLC, we all need to be prepared for the possibility of death while still owning substantial value in the farm business.

Farm business assets cannot be sold off on a whim; they are necessary to keep the business running. If Gen 2 dies without proper planning, first the debts of the farm are paid, then estate taxes may be due, and there may be little to no cash on hand to pay those bills. Some of their children may also appreciate a gift of cash rather than property or ownership interests in the farm. In the estate planning process, we have to build in some liquidity—a way to generate cash—to pay the bills without selling off critical farm assets.

The traditional way of providing liquidity when someone dies is by purchasing life insurance on the life of that person so that when that person dies, there is cash available for different purposes. This can be particularly important in the case of farm succession and estate planning because for most farms, the real value is in real estate, which is not liquid. Liquidity makes it easier to pay bills, make a cash distribution to a beneficiary, pay down a mortgage to make continued operation of the farm more achievable, or pay estate taxes without having to sell something.

Life insurance is a contract between the owner of the life insurance and the life insurance company. The life insurance contract specifies the person whose life is being insured. The life insurance contract also specifies a beneficiary. A life insurance contract requires the payment of a premium. And then there is the party that pays the premium. Therefore, a life insurance contract can involve at least four different parties:

- Insurer: The insurer is the life insurance company.

- Owner: The owner is the person or entity that gets to decide who the beneficiary of the policy is.

- Measuring life: The measuring life is the person whose life is being insured. When this person dies, the life insurance contract is triggered, and there is a payout.

- Beneficiary: The beneficiary is the person or entity that will receive the payout.

The owner does not have to be the party that pays the premium or the party that is the measuring life. The owner, the measuring life, and the beneficiary can all be the same. But if the decedent is the owner, the payout will be included in the decedent’s taxable estate. In other words, the decedent’s estate will pay estate taxes on the payout. That will be true whether the decedent’s estate is the beneficiary or not. This creates a conundrum. Life insurance with Gen 2 as the measuring life is often purchased with Gen 3 as the beneficiary to help pay estate taxes upon the death of Gen 2. But if that policy is owned by Gen 2, then the payout increases the taxable estate at the same time. A work-around has been created, but it is very complicated and full of tax and other traps. It should never be attempted by anyone other than competent legal and tax counsel. It is called an irrevocable life insurance trust, or ILIT. It involves the creation of a very specialized trust that functions as an irrevocable or unchangeable separate entity. Simply put, the ILIT becomes the owner of the life insurance policy with Gen 2 as the measuring life and Gen 3 as the beneficiary with the goal of using the payout to pay estate taxes or other expenses associated with the death of Gen 2 while not including the payout in Gen 2’s taxable estate. ILITs are complicated to set up and require annual maintenance. The family must be committed to take on this complication and expense before considering establishing one.

However, one benefit of life insurance is that the beneficiaries, usually a trust, spouse, or child, do not pay income tax or other tax on life insurance proceeds. If the farming Gen 3 is going to receive a high-value stake in the farming operation and other nonfarming Gen 3 children do not want to be part of the business, life insurance proceeds can help provide a distribution of Gen 2’s assets so that all children are taken care of. It can also be used by the heirs to pay for estate costs or any estate taxes that are estimated to be due, which avoids the sale of farmland or other valuable assets to pay for the tax bill.

In conclusion, life insurance can provide needed liquidity, but it should be included in an overall estate plan only after consultation with and under the direction of competent legal and tax counsel with the involvement of a competent insurance advisor.

Step 5—Create the estate plan.

- Continue to consult with your family members about their wishes when you decide how to create a gift for each of them in your estate plan.

- Consult with your professional advisors about any additional insurance or financial instruments you need to address estate taxes (if they apply) and to give gifts to nonfarm family members.

- Review your plan on a regular schedule, and update it as circumstances change.

A person who is entitled to receive a deceased person’s property due to family relationships under the state’s laws of intestacy, which govern the distribution of an estate when there is no will. In common use, can also refer to a person who inherits under a will.

The legal right established in joint ownership of property allowing the surviving owner of the property to take the interest of the person who has died automatically without going through probate. Exists when property is owned by joint tenants with rights or survivorship or by tenants by the entirety.

Designation that allows beneficiaries receive assets at the time of the owner’s death without going through probate. It may be used on accounts, securities, and deeds in Oregon. Beneficiaries have no access to or control over the assets while the owner is alive.