Chapter 3: Organize the Farm Business Limited Liability Company (LLC)

When organizing a business, the first thing we talk about is risk. Every business can and should use legal tools to manage risk by limiting the liability of the owners for the acts of the business. Tools include separate business entities, proper and complete insurance coverage, complete and well-structured contracts, lien rights, and other legal protections to manage risk. We have already discussed several of these tools. Now we will focus on organizing separate business entities.

Using well-designed business entities to separate assets from activities with higher potential business risk is key to ensuring the viability of the farm business and passing on the maximum value of the business to the next generation in the succession process. In addition, creating separate legal business entities can streamline the farm succession process by setting up clear rights, responsibilities, and expectations among everyone involved, even the nonfarming family members.

Every operation is unique and faces its own risks, but there are some common tools that help all farms manage those risks and help ensure their long-term business viability—namely, business entities with limitations on liability for their owners called “limited liability business entities.” It is important to understand that despite the use of that term, limited liability business entities do not necessarily have limits on liability for their own actions. These business entities are used to separate business assets from personal assets so that business liability threatens only the business assets. Because this isn’t a comprehensive solution, maintaining insurance and taking other risk-management steps are still key.

A. Why Form a Business Entity under State Law?

There are two broad categories of business entities: those in which the owners have liability for business debts and judgments (sole proprietorships and general partnerships) and those that are able to provide the owners with some liability protection if constructed and maintained properly (LLCs, limited partnerships, corporations, and cooperatives).

Around 80 percent of Oregon farms and ranches are currently considered sole proprietorships or partnerships—which implies that many farms have not started their succession planning process.

Sole proprietorships are the “default” business entities that are formed if you just start doing business, and they have unlimited personal liability for business actions. If the business assets are owned and controlled by one person, it is called a sole proprietorship. This means that all the business assets are held in the owner’s personal name—the land, equipment, livestock, and so on—and all debts and contracts are taken out in the owner’s name. The business may have an assumed name that is used for marketing, but it does not give further legal protections.

General partnerships are similar to sole proprietorships, but the business assets are owned and controlled by more than one person. Again, all assets and debts are owned in the partners’ names, and each contributes personal assets to the partnership. Each partner is seen as an authorized agent of the business, which means that one business partner can sign a contract or loan or otherwise incur liability for the business without consulting the other(s), and all partners are liable on the debt. Business partners share everything—assets and profits along with liabilities and debts. Like a sole proprietorship, there is no separation between a partner’s personal assets and the business and its debts and liabilities, resulting in unlimited liability so that if a creditor sues successfully for a business debt, they can also get paid from the farm owners’ personal assets, such as bank accounts, vacation homes, or other personal property. While the advantage of sole proprietorships and general partnerships is that they are simple to form—if you own the assets and start doing business, you are governed by their rules—the disadvantage is that they do not protect your personal assets from business risks.

Operating a sole proprietorship complicates the succession process after the death of the owner and is likely to result in substantial loss of business value in the transition, even if a will or trust has been established.

Around 80 percent of Oregon farms and ranches are currently considered sole proprietorships or partnerships—which is a concern because organizing the business as a limited liability entity is a first step to business succession planning, implying that many farms have not yet begun the planning process. Operating a sole proprietorship complicates the succession process after the death of the owner and is likely to result in substantial loss of business value in the transition, even if a will or trust has been established. Transferring the ownership of each of the owner’s business assets to a new generation takes time and money and is not always structured in the best interest of the business.

Limited liability business entities separate the business liabilities from your personal assets (unlike sole proprietorships and partnerships). Separating personal assets from business liabilities is the primary reason for creating a limited liability business entity. Transforming your farming operation into a limited liability company (LLC), for example, involves filing articles of organization with the Oregon secretary of state, using the appropriate forms, creating an operating agreement, filing the new entity with other regulatory agencies related to such things as taxes and employment, and operating the business according to the rules. The important distinction is that the business is recognized as its own legal “person” in the eyes of the law. It is separated from your personal assets. Unlike a general partnership, owners of the LLC cannot make decisions on behalf of the business or other owners unless they are authorized to do so in the operating agreement. The business entity can own property, enter contracts and loans, sue, and be sued. The business entity stands in the place of the business owners. Therefore, if the business is sued or defaults on a loan, the business and its assets carry the burden of the risk, not the owners.

Of course, the owners put their investment in the business, and that investment is at risk. No entity operates behind a perfect magic legal shield; people can still sue the business for debts and liabilities. But if operated correctly, it limits the owners’ liability to the assets that they have invested in the business. When done right, and without the presence of other circumstances leading to an owner’s personal liability, it provides some protection for personal assets in lawsuits or other claims. Your business lawyer may advise that you would be better off setting up your farming operation as an LLC because a shield, even if not bulletproof, is better than no shield when you are being sued.

B. Choosing a Business Entity

Every business operates within the legal rules of the county, state, and federal government. The types of entities available to form a business and their primary characteristics are established by the state. The state also creates and enforces the laws regarding contracts, loans, property, and torts.

In short, you should choose the business entity available in your state that carries the right mix of limits on an owner’s personal liability for business debts and judgments, minimizes taxes when moving assets around, maximizes your ability to control the business, and is manageable to administer while facilitating your ability to pass the business on to the next generation. Only a skilled business lawyer familiar with you, your business, and your goals and aspirations can advise you on the correct business entity for your purposes. Here we will discuss some of the choices available in Oregon with the hope that this information will help you ask questions of your legal, tax, and financial advisors and understand the implication of their recommendations as you make the right choices for your family and business.

Most lawyers will begin by pointing out the need to organize the farming operation as a form of business entity that will separate its actions and other liabilities from the owners’ personal assets and the farm’s hard assets, like land or livestock. This will provide some protection from liability to its owners. No business organization can provide perfect separation or perfect limitation of liability for the owners. It’s a risk management tool, not a risk elimination tool, and there is no perfect solution. Further, improper business formation and lack of careful maintenance can erode even the most basic aspects of separation and liability protection. Everything must be set up and maintained correctly for the owners to enjoy the benefits of business organization.

Key legal advice: separate the farming activity from the ownership of land to protect the value of the land from legal judgments that arise from farm operations.

That said, most business lawyers will begin by advising the farm owners to separate the farming activity from the landowning activity. The simple goal is to place a barrier against liability between the entity with the greatest likelihood of injuring someone and the entity that owns the farm’s most valuable asset—land or cattle. Therefore, the typical first step in a business succession plan is to get the farming operation itself—the activities of buying, selling, farming, hiring, and so on—into a separate organization from the farm’s hard assets, such as the land, and the owners’ personal assets.

Here we will discuss the characteristics of LLCs rather than corporations or other limited liability business entities. We will analyze the LLC in the context of the four main goals for choosing a business entity previously discussed. There are other entities available that offer limited liability, but these vary in their tax requirements and other implications; they are corporations, limited partnerships, and even nonprofit corporations, which your operation could be qualified for if it had a charitable purpose. Corporations, for example, are much less flexible than LLCs and so are rarely used unless there is a high operational risk, such as selling food directly to the public. Currently, most for-profit family farms seem to be choosing the LLC to organize their operations, so we will focus on that in this guide (see table 3 for LLC terminology)

|

Name |

Farm Name LLC |

|

Owners/investors |

Members |

|

Who makes management decisions? |

Managers or members (depending on whether a manger is hired who is not also a member) |

|

Creation document |

Articles of organization filed with secretary of state and $100 fee |

|

Governing document |

Operating agreement |

|

Owner’s investment |

Capital contribution |

|

Ownership share |

Membership interest defined in terms of a percentage |

|

Payment of profit to the members |

Distribution |

|

Payment of a salary to a member |

Guaranteed payment |

|

Are members personally liable for LLC debts or judgments? |

No. Liability for business debts and judgments are limited to a member’s capital contribution if LLC integrity is maintained. In Oregon, a judgment against an LLC results in a charging order against LLC distributions. |

|

Can a creditor have a legal claim on a member’s personal assets? |

Not usually, but creditors may “pierce” the LLC veil if members comingle personal and business funds, do not follow legal requirements for the LLC operation, or undercapitalize the LLC. |

|

How many members can an LLC have? |

One or more; can be individuals, other business entities, or trusts |

|

Are annual meetings required? |

No |

|

Is there ongoing reporting to the state? |

Yes, you must appoint and maintain a registered agent who has a physical street address in Oregon and fill out a renewal form with the basic LLC information (name, registered agent, member names, etc.) with $100 fee. Due on the anniversary of formation. |

|

How are LLC profits taxed? |

You can elect the pass–through method of taxation: members file and report the LLC’s income on their own separate personal income tax returns based on percentage membership interests owned. If you do not elect pass-through taxation, the LLC is double taxed: once on its profits and again for each member. |

C. Forming an LLC

The legal formalities of starting an LLC are relatively easy—just fill out and file articles of organization with the Oregon secretary of state, pay a small fee, and capitalize the LLC by moving existing farm assets into the LLC’s name. You should also create an operating agreement for the LLC.

The articles of organization can consist of a simple form supplied by the Oregon secretary of state’s office. In it, you report the basic information about the LLC, register an agent to be served in the case of a lawsuit and a person and a place to receive official LLC mail, and pay a fee. In 2019, the filing fee for the articles of organization was $100. Then you will file a renewal form every year on the anniversary of the LLC formation with the same basic information (updated if necessary) and a $100 fee.

The operating agreement defines the rights of the LLC members (owners) and managers. While there are default state rules that govern the relationship between LLC members, it is wise to also create your own operating agreement. Writing an operating agreement that considers the unique complexities of your family and farm business takes some care and attention. After thinking about the options, you can use the help of an attorney to craft the right operating agreement for your situation. For example, in a multigenerational LLC, it is important to clarify who has management control, what members without management rights can vote on, and how votes are counted. It is also wise to set the rules for LLC distributions so that there is no confusion down the road. To keep the LLC in the family, there should be buy-sell agreements for all member shares, so that if a member wants to leave the LLC, they must sell their shares within the family or the LLC can buy them out, with a valuation method and payment schedule defined so that a departing member does not drain the LLC of operating cash. Family members can also decide in the operating agreement the procedures for dissolving the LLC if they decide to liquidate the business.

While there are no annual meetings or formal recordkeeping requirements as with a corporation, it is wise to have meetings and keep excellent records of decisions to protect the LLC member-managers if other members are unhappy with the business direction at some point in the future. It’s also just a good idea to keep track of the decisions that have been made by the business.

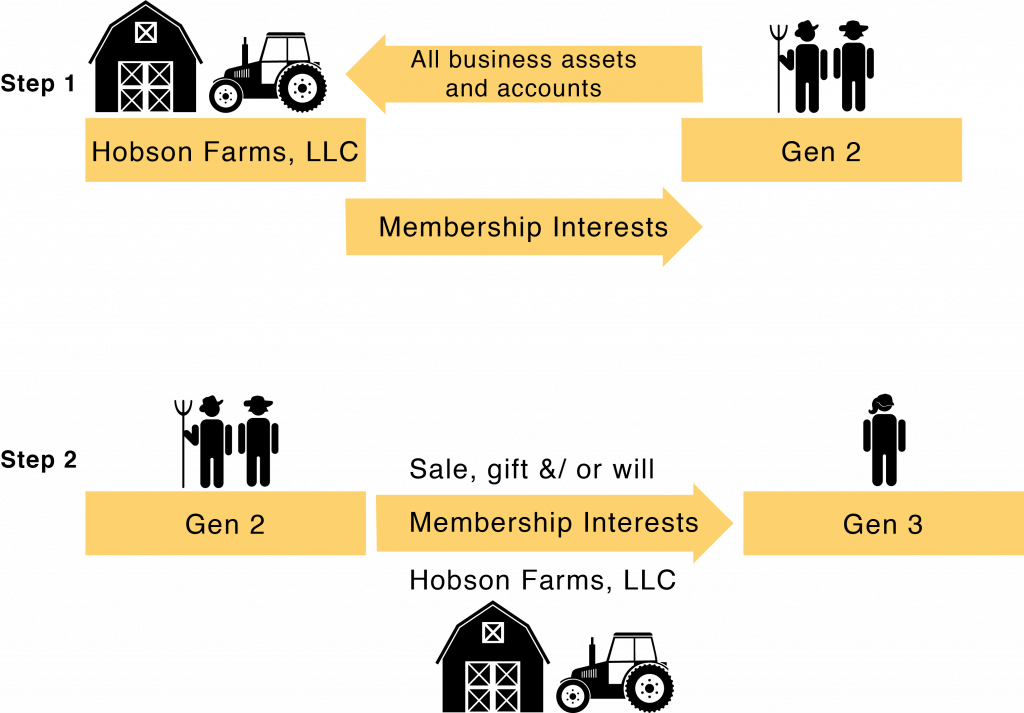

Capitalizing the LLC from an existing farm business involves moving farm assets from Gen 2’s personal ownership to LLC ownership, which represents their capital contribution to the LLC. In exchange, Gen 2 owns all the membership interests in the LLC (figure 4, step 1). Gen 2 can then gift or sell membership interests to other people, including family members, immediately or over time (figure 4, step 2).

D. Operating an LLC

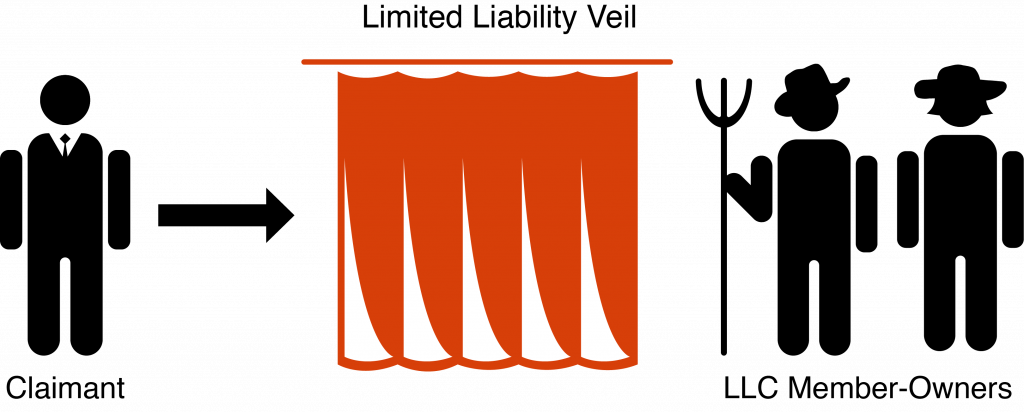

The limited liability veil of the LLC can be “pierced” if the business is not operated as a separate legal entity, such as keeping separate accounts for business income and expenses. If you comingle business and personal funds, such as using business funds for personal expenses, you could also be personally liable on the debts or liabilities of the business.Operating the business as its own separate legal entity is one of the keys to maintaining the limited liability aspect of an LLC. If someone sues the business, they may “pierce” the limited liability veil of the LLC and go after the owners’ personal assets if they can prove that the business was not operated as a legal entity that is separate from the individual members of the LLC (figure 5). This exposes the owners’ personal assets to full legal liability for business debts or judgments. The business must have adequate capital to engage in certain functions, such as paying its monthly bills and loans, buying inputs as needed, or paying for other expected expenses. For example, if the business takes on more debt than it can reasonably pay off with expected revenue, the LLC will be considered undercapitalized.

In addition, business accounts must be kept separate from personal accounts. Business accounts cannot be used for personal expenses. The business can pay reasonable wages and bonuses to employees, who may also be owners, and profits may be distributed to owners as well. Therefore, it is critical to keep the business assets and accounts separate from personal accounts and maintain proper accounting and business records.

Keeping the business accounts separate from personal accounts can have other benefits, especially when there are multiple generations that own the business. Keeping separate business accounts allows managers (and potentially creditors) to evaluate the viability of the business as a business to see if the farm is making enough income to maintain and grow over time. If owners have to keep putting personal assets that come from other sources into the business, such as off-farm work, the business may not be viable for the long term unless changes are made. Keeping business accounts separate also ensures transparency so that all family members with an ownership interests trust that the business is being managed properly. If a family member who is the owner-manager is paying for personal expenses out of business accounts, it will undermine trust and lead to conflict.

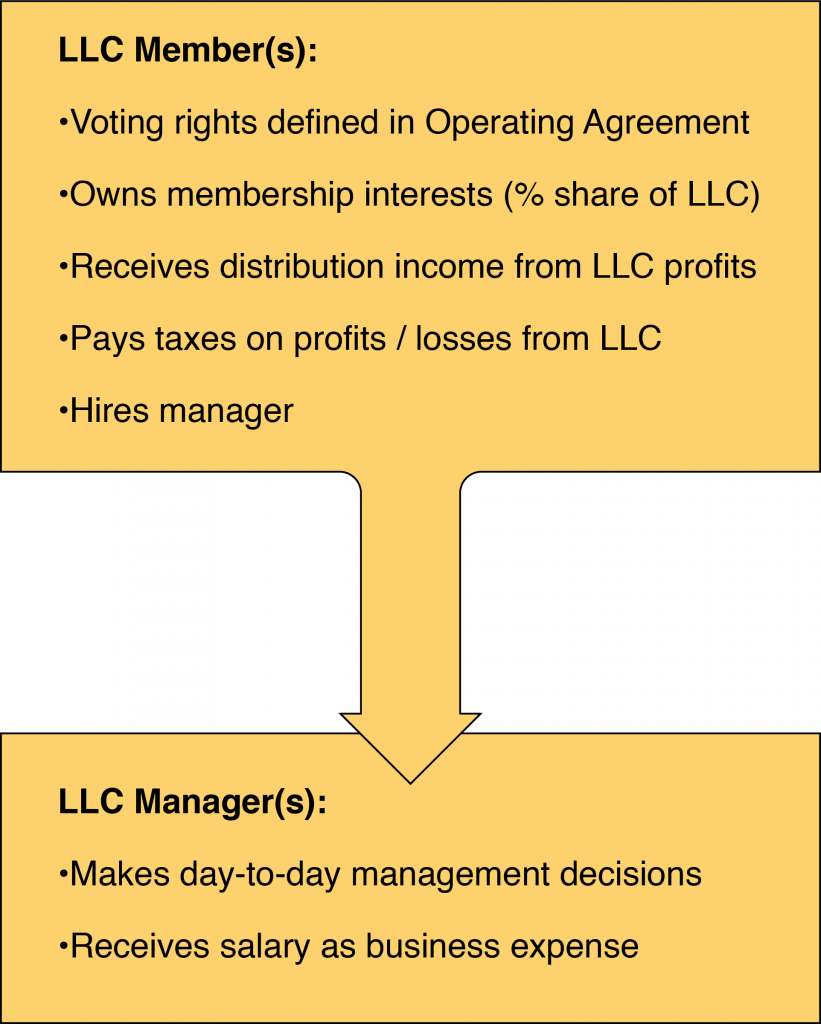

Rights of owners. The LLC is a flexible business entity that allows the farm owners to determine their rights in the operating agreement when the LLC is established. One or more people can be members of the LLC. If there is only one member, then there is full ownership and control exercised by one person. If there is more than one member, such as in a multigenerational extended family LLC, many people can be members of the LLC with varying “membership interests,” which represent their percentage of ownership in the whole business. The beauty of the LLC is that the business owns all its assets. The people that own the business own a portion of the value of the business, shared with the other members.

If the LLC is member managed, then one of members can be both an LLC member and day-to-day business manager. The other member-owners who are not managers do not have day-to-day management powers, so they cannot interfere with daily management decisions. The operating agreement can give member-owners voting power over big-picture business decisions in accordance with their ownership shares and define the types of decisions that they can vote on. Member-owners are also entitled to a distribution of the LLC’s profits based on the percentage of their membership interest in the LLC.

LLC members also have the right to share in the business profits and losses. When the LLC has a profit at the end of the year, it can distribute some or all of that profit to the members, typically in proportion to each member’s percentage membership interest.

Taxes. LLCs are eligible for pass-through taxation, another favorable characteristic of LLCs for a family farm business. After talking to your tax attorney and accountant, you may elect to use pass-through taxation, which you indicate on your tax return. By using pass-through taxation, the business’s profits and losses calculated at the end of the year are “passed through” to the owners according to their percentage membership interest, and then the owners are taxed on the income on their personal income taxes. The sole proprietorship and general partnership also enjoy pass-through taxation, but as we saw, they do not have limited liability.

The alternative to pass-through taxation is referred to as “double taxation,” which is the typical tax treatment for a C corporation. The corporation itself is taxed on its profits at a corporate tax rate, and then the after-tax profits can be distributed to owners who pay personal income tax on the dividends that they receive from the corporation. For many taxpayers, double taxation is a downside to the corporate business form.

Ease of administration and succession. LLCs are relatively easy to set up and maintain compared to corporations. While sole proprietorships and general partnerships require no paper work, the small amount that is required for an LLC is more than worth it for the great benefit of limiting personal liability for business debts.

E. LLCs for Succession Planning

The biggest benefit of an LLC for business succession planning is the ability to separate business ownership from management control (figure 6). Gen 1 and 2 members have worked hard to build up the business, with the support and sacrifice of all their family members. They should be able to continue to reap the financial benefit of the business and share that with their other nonfarming family members. All family members can be LLC members. They are entitled to distributions from the profits of an LLC and can have big-picture decision-making input as defined in the operating agreement.

The Gen 3 operators who are coming back to the farm will want to be able to manage it on a day-to-day basis without interference from other family members who have ownership interests. The LLC operating agreement allows a clear separation of business ownership from management control.

When Gen 3s are ready to start working with the Gen 2s on the farm, they may start as a junior manager and may get some membership interests as part of their compensation package. Over time, they may earn or buy more of the membership interests until they move into the full management role with day-to-day decision-making power and own a controlling share of the membership interests. This allows Gen 2 to train Gen 3 as they grow into the position and allows Gen 2 to reduce their labor and control over the business until they are ready to retire. It also allows other family members to join in the financial benefits of the business without having management control.

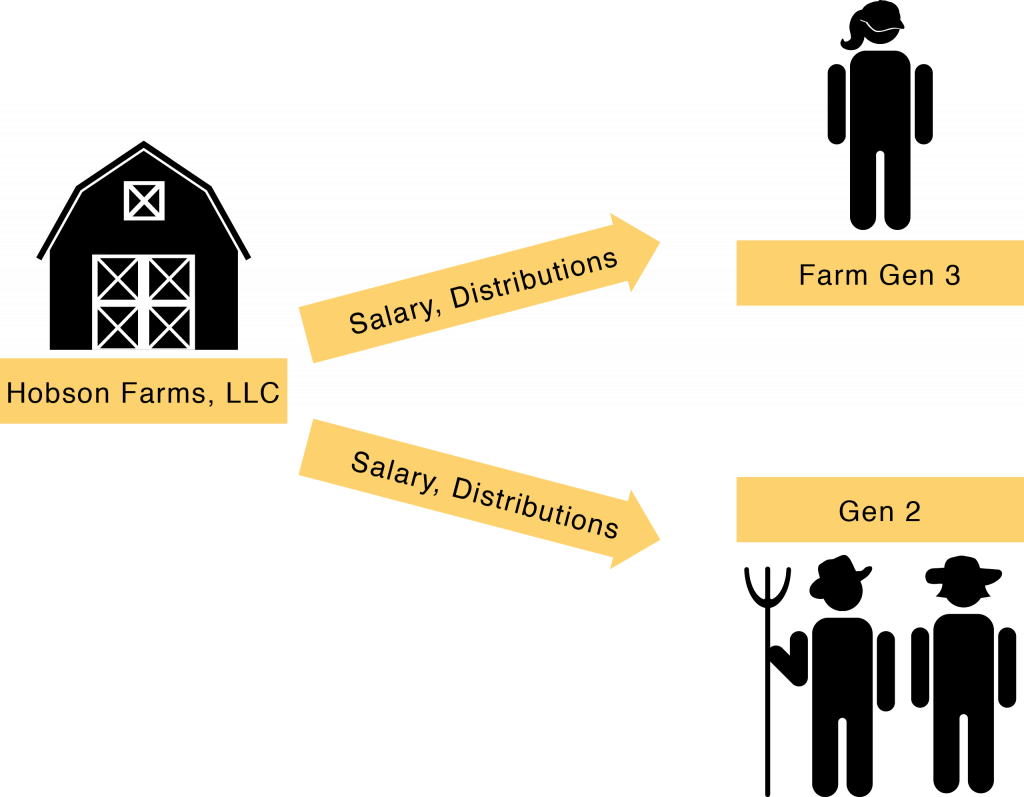

The LLC structure also creates income streams from the profits of the business that can be defined according to the family’s needs. An LLC allows retiring Gen 2s, nonfarming family Gen 3s, and the farming Gen 3s to receive distributions from farm profits. Each owner receives distributions from profit in proportion to their membership interests. Meanwhile, the Gen 2 and Gen 3 farm managers are paid a salary for the labor that they contribute to operating the farm (figure 7). If Gen 2 is cutting back on management duties as they enter retirement, the salary of Gen 2 and Gen 3 managers can be adjusted to reflect their level of effort. If Gen 3 is acquiring ownership interests in the LLC via an option to purchase or as part of his or her compensation package, the distributions from farm profits to Gen 2 and Gen 3 as owners also reflect the percent ownership interest that each has in the LLC.

Looking ahead to estate planning, putting the farm into an LLC also allows Gen 1 and Gen 2 to pass their membership interests in the LLC to younger generations as gifts while they are still alive to reduce their taxable estate, and they can decide how any membership interests they own will be distributed to their surviving family after their death. Holding the business as an LLC simplifies the estate planning process, separating business assets from the personal assets of Gen 1 and 2 and making division with the next generation much easier and more straightforward.

Step 3—Organize the farm business limited liability company (LLC).

- Get recommendations from other farmers or ranchers or see the “Resources” section to find an attorney who is equipped to work with your farm business and one who you are comfortable with. Conduct several interviews.

- Carefully consider the rights of the LLC owners so that they have clear boundaries between owners’ authority and management’s authority. Consider which family members should have the right to be an LLC owner. Your attorney can help you write an operating agreement that creates clear rights and responsibilities for everyone involved.

- Remember that organizing the farm as a legal business entity provides immediate risk-management benefits and doing it as part of your business succession plans will ease the succession and estate planning process down the road.

A business entity in which two or more people operate a business for profit and agree to share all profits and losses and financial and legal liabilities. Partners are all agents for the business and can bind the business to contracts, loans, or legal judgments without the consent of the other partners. A general partnership does not have limited liability, so personal assets of all the partners can be claimed to satisfy judgments or debts against the business.

One who is authorized to act on behalf of another (the principal). For example, in a general partnership, all partners are authorized as agents to make business decisions, enter contracts, and the like on behalf of the business, which binds all other partners.

Document filed with the secretary of state when forming an LLC to legally register the business entity with the state. Includes basic information about the LLC: company name, duration, principal office street address, registered agent to receive legal notices, management (member managed or manager managed), name of organizer(s), owner(s), manager(s).

Describes the rights and responsibilities of LLC members, setting out the terms and conditions that all members agree to, such as voting rights; manager duties, qualification, election, and removal; distribution of profits; procedures for adding new members and who qualifies; meetings; buy-sell agreements; dissolution of the LLC if desired; mediation or arbitration of conflicts; and so on. If the LLC does not create an operating agreement, existing state laws will govern any dispute among members or managers.

A legally binding contract that stipulates how a business owner’s interest may be bought and sold if that owner dies or leaves the business. Typically, the buy-sell agreement requires the ownership interests to be sold to the remaining business owners or the business must buy back the interests.

There are different ways to determine the value of the farm business, depending on the circumstances. The net balance sheet value is the current assets minus the liabilities. A liquidation approach would determine the value if all assets were sold and liabilities paid. The business can also be valued by calculating the present value of its earning potential over time or by looking at what similar businesses are selling for if they change ownership as a going concern.

Ownership stake in an LLC that represents a percent interest in the business and corresponds to voting rights and distributions.

Holding insufficient funds to carry out the business purpose of the LLC. If an LLC is undercapitalized, the owners may be vulnerable to piercing the limited liability veil so that their personal assets are at risk in the event of a judgment or debt collection.

A taxation in which a business is not taxed directly on profits. Profits are “passed though” to the owners, and the owners report the amount on their personal tax returns. LLCs can elect pass-through taxation.

Tax treatment of a C corporation, which pays taxes on corporate profits based on the corporate tax rate, and then the remaining profits distributed to owners are taxed as dividends on owners’ personal tax returns.