Chapter 6: Marketing Functions

After reading Chapter 6 you should understand the following:

-

- The link between marketing functions, strategies, and structures.

- How the forest industry utilizes communication in marketing.

- The importance and practice of customer support in creating a total product.

- The challenges of pricing forest industry products and the potential impacts of moving toward special and custom-made products.

- The role of marketing in product development.

- The basic methods of transporting forest products.

Marketing functions are those mechanisms or tools that allow a company to carry out its strategies via its chosen marketing structures. For example, if a company is basing its competitive advantage on high quality products and service, the most important marketing functions might be product development and close contacts with customers. Marketing functions can be divided into those that are under the full control of marketing specialists, which are focused on communication (contact functions), and those functions in which marketers only participate as part of a team (product functions). Here are some of the functions in both categories, which are covered in this chapter:

Contact Functions

- Personal contacts (personal selling)

- Advertising

- Public Relations

- Trade Promotion

- Customer Support (customer service)

Product Functions

- Pricing

- Product Planning/Development

- Physical Distribution

Because much of marketing is about communication and the basic concepts of communication are an essential component of many of the marketing functions, we begin the chapter by providing a brief overview of communication, and specifically discuss communication with respect to marketing.

6.1 Basics of Marketing Communication

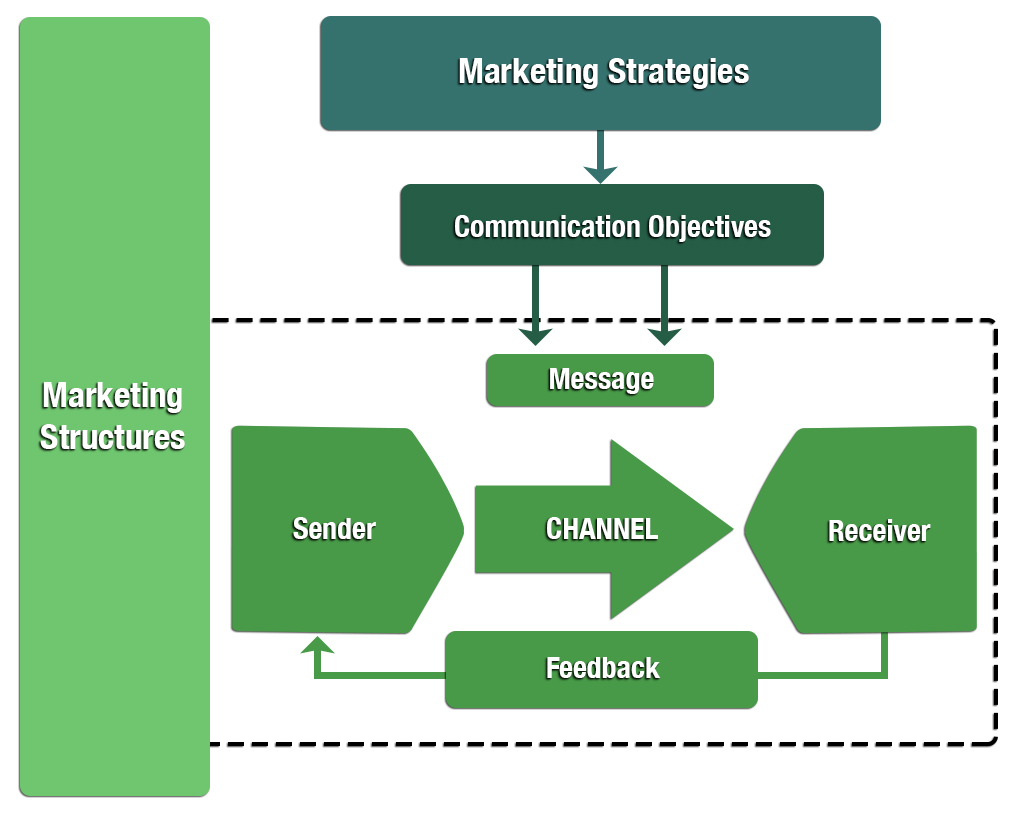

Communication and communication planning can best be understood through the use of a model (Figure 6-1). Planning marketing communication begins with the Integrated Model of Marketing Planning (IMMP), from which marketing planning targets are derived, and is then integrated with a general communication model. We emphasize that planning and executing marketing communication measures require special expertise.

6.1.1 Basic Communication Model and Concepts

Communication is transmission of information by sending and receiving messages. Traditionally, the elements of communication have been considered to be:

| Who | (Sender) |

| Says what | (Message) |

| Through what method | (Channel) |

| To whom | (Receiver) |

| With what effect | (sender’s objective/resulting effect) |

The last element suggests the fundamental issue of communication – what is its effect? How does communication influence knowledge or change opinions, attitudes or behavior? These are also the basic questions of marketing communication.

The basic components of communication – sender, channel, message, receiver and feedback – can be referred to as “the Basic Model of Communication,” and form the core of Figure 6-1. For our purposes, the core is surrounded by certain elements of marketing planning (IMMP), and together, the figure contains the principles of marketing communication planning which will be discussed more thoroughly in this section. “The Basic Model of Communication” is a simplified version of more complex communication models.[1]

Message – When a salesperson makes a phone call, or an advertisement is created, or an executive gives a presentation, a message is presented. The message might be that a new product is launched, or that a special price is available, or that a product has a certain level of quality, or that a company has a responsible environmental policy. The message is the knowledge that the sender wants the receiver to gain. Throughout its communication activities, a company must exercise great care to communicate a cohesive and focused message. Conflicting messages will be unproductive at best and, at worst, will disrupt and weaken the image a company has worked to create.

Sender – We can think about the sender as the company, the salesperson, or the corporate executive. Sometimes distinguishing between sender and channel may be difficult. When a company uses an expert to promote its products, the receiver may find it difficult to determine if the sender is that expert or the company behind the promotion campaign. We interpret the sender as the individual or organization that initiates the message.

Receiver – The receiver is the company, individual, institution, or stakeholder group to which the message is targeted.

Channel – The medium through which the message is sent is the channel. On a basic level, the channel is either personal or non-personal. The division is sometimes referred to as natural and artificial. For instance, an advertisement might be in print form, on the radio, or online; all non-personal forms of communication. A salesperson, however, might provide a verbal (personal) message face-to-face with a client or over the phone. Successful communication depends on choosing an appropriate channel that fits the needs of the receiver.

Feedback – The model of communication planning provides for a feedback loop, with communication traveling in both directions. In some forms of marketing communication, there is little likelihood of direct feedback. For example, an advertisement may not result in direct feedback, though an inquiry or product purchase would constitute indirect feedback. Internet communication provides for easy feedback.

Earlier, “effect” was mentioned as a basic issue of communication. Traditional communication research has focused on identifying the circumstances under which communication can influence knowledge, opinions, attitudes and behavior. Example 6-1 illustrates issues inherent in communication, according to a wide base of research.

Example 6-1: The Basics of Communication

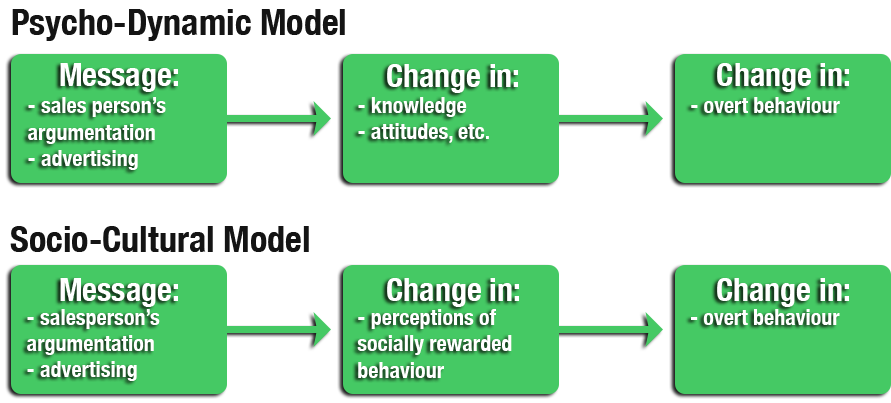

Before designing the communication mix (sender, message, channel and receiver), the communication planner must choose the basic approach or philosophy of influence. DeFleur (1966) presents two basic models of influence outlined in the figure: 1) Psycho-Dynamic Model and 2) Socio-Cultural Model.

According to the Psycho-Dynamic Model, the persuasive message has an effect on a person’s psychological structure and processes like attitudes. Change in attitudes creates change in behavior. Principles of motivation, perception and learning theory are central when planning channels and messages that influence attitudes and behavior. The Psycho-Dynamic Model emphasizes the individual motivators of human behavior. For example, by promoting wood as an environmentally friendly material, we present product comparisons to the customer, suggesting its renewability and other healthy aspects of wood. The communication attempts to create positive attitudes leading to corresponding behavior.

The Socio-Cultural Model emphasizes the social motivators of behavior. This model is based on the idea that cultural norms have effects on human behavior. When using the principles of the Socio-Cultural Model, the receiver of the message is made to believe that the behavior promoted is socially sanctioned. For example, when promoting wood as an environmentally friendly material, we emphasize that modern societies take care of their environment and it is a good deed to use an environmentally friendly product that helps preserve the environment for future generations.

Once the basic approach has been chosen, the communication planner must design the communication mix. Extensive research has been conducted to determine the basic concepts in using each of the elements of communication (Secord and Backman 1964). Below are some examples regarding the sender, message, and receiver. However, communication planning is an area of specialty that cannot be thoroughly covered in a marketing textbook.

Sender – Effectiveness of the sender in persuasion depends on how the receiver perceives the expertise, reliability and intentions of the sender. A person perceived as reliable or as an expert is more influential than a person without these characteristics. Among Central European consumers, environmental organizations (ENGOs) are a very important source of environmental information, most likely because consumers trust the intentions of ENGOs more than those of industry.

Message and Receiver – The message must fit the personality, intelligence, cognition, and attitude of the receiver. Communication research has carefully considered the following aspects of the message:

● How much information should the message contain?

● Should the information be one-sided or many-sided?

● What should be the order of positive and negative arguments?

● Should negative aspects like fear be used in persuasive messages?

The effectiveness of both quantity and the use of one or many-sided information depends on the knowledge level of the receiver. The lower the knowledge level, the less information should be used. The higher the knowledge level, the more information is needed, and this information should be many-sided. As to the order of information, results are better if positive arguments are presented first. Positive arguments reinforce positive attitudes that resist negative arguments. Fear as an argument may cause fast behavioral changes, but fear-based arguments may backfire if targets react negatively to the message. With respect to how social structures can be employed when planning communication, opinion leaders are often the targets of communication because of their role in disseminating information to others in their social groups.[2]

6.1.2 Principles of Marketing Communication Planning

Marketing communication can be broadly defined as managing company information flows to the market, in the market, and from the market (some of which is outside the control of the company). A narrower definition might be that marketing communication is the communication effort designed to create demand or other market reactions, such as perceptions of company image which can have a long-lasting effect on future demand (Example 6-2).

Example 6-2: The Power of Image

All companies attempt to portray a specific image to their customers. The most obvious examples are global consumer/service products companies such as Alphabet, McDonalds, or Adidas. For most people, these names instantly conjure up an image. Sony might mean highly reliable electronics, McDonalds as fast hamburgers and fries, and Adidas as the brand with “three stripes.” These images are not accidental. Each company has staked out market territory and used a variety of communication techniques to record that claim in the customer’s mind. This effort is called image creation or positioning, and both are important communication concepts. Sometimes companies stumble and the result can be very negative for their image. Volkswagen’s image suffered greatly in 2015 based on a scandal around using a “defeat device” in its diesel cars that engaged when pollution testing was being conducted (but otherwise the vehicles were polluting above accepted levels). This strain on the reputation provided inroads for competitors. Similarly, if a spokesperson for a brand has personal problems, it can have a negative impact on brand image. Several sponsors dropped Tiger Woods as a spokesperson after his personal debacle in late 2009.

When speaking about marketing communication, one should specify point of view because appropriate characteristics of channel and message depend on the objectives of the marketer (sender) and customer (receiver). According to the definition of marketing, the marketer should choose channels and messages to steer purchasing decisions towards the company’s products. The customer, in turn, is searching for information in order to make relevant product choices. It is important that the marketer realizes the possibility of conflict between the two views, and plans the communication portfolio accordingly.

The planning situation of marketing communication can be analyzed through Figure 6-1, which shows the connections between communication and marketing strategies and structures. Marketing communication planning can be seen as having two stages:

- Deriving communication objectives from marketing strategies and outlining the company’s communication portfolio based on strategic marketing context.

- Creating detailed plans for communication targets (receiver), messages and channels.

Stage one is clearly the task of the marketer who must also be able to brief the advertising agency about the company’s strategic marketing situation and needs. Stage two is the task of an advertising agency that has knowledge and skills to plan and execute marketing communication campaigns. We detail the cooperation between the marketer and advertising agency later in this chapter.

When a marketer begins to contemplate how marketing communication should be developed, the company has already settled on its marketing strategies and marketing structures. From the marketing strategies (especially products and core competencies) flow communication objectives, which in turn influence the message. When customer strategies are identified, they in turn define the receiver shown in the model. Customers, by their unique characteristics, in turn define the possible channels. The model of marketing communication planning should be used to guide decisions integrating various aspects of the communications portfolio (see section 6.2).

The marketing communication plan is a compatible combination of the concepts seen in the communication model. The success of the plan depends on how well the planner understands the various concepts of communication and their interdependence. In the following section, we explore the connections among the basic concepts of communication.

Receiver Considerations

A prerequisite to success in marketing communication is a receiver with a need. The receiver must be motivated to seek and use the information in the message – marketers should never assume the customer is a passive information receiver. It is useful to see the customer as an active information seeker, and the marketer as someone who can make finding beneficial information as easy as possible. If a marketing channel intermediary is the target of the marketing communication, for example, the marketer is seeking to assure that the intermediary is motivated to promote the supplier’s products.

Communication efforts can be designed to pull or push a product to the consumer. By focusing its communication efforts on the final consumer, a company positions its products to be pulled through the marketing channel. For example, the Hardwood Manufacturers Association maintains the American Hardwood Information Center that focuses on final consumers. A push strategy is more common among forest product companies; here, a company might focus its efforts on the members of the marketing channel and attempt to get those companies to push the product through to the final consumer. Still, both push and pull communication tactics have their place in a company’s marketing functions, and they can be combined to suit the specific situation. A pull strategy offers more direct control over the product and company image, while a push strategy allows the company to benefit from the intermediary’s promotional skills. The push strategy is most effective if intermediaries are fully motivated to increase the demand of a company’s products.

Communication efforts must be targeted toward individuals making decisions concerning purchases or end-uses of products. Alternatively, communication can be targeted toward others who influence those decisions. In push tactics the intermediaries have a clear economic motive to promote the products. Experts and opinion leaders often have a direct influence on customer decisions. The marketer must know where customers acquire information and on whom they rely. This information is then used when choosing the targets and channels of marketing communication.

In many cases, industrial buying decisions are made by a group of individuals, and consumer decisions are often made by families, where roles are clearly differentiated. For example, certain decisions regarding the selection of materials for single-family homes are made by the wife, while others are made by the husband, and still others are made collaboratively. When the marketer targets communication to families or other groups, the roles and communication behavior in the group must be taken into consideration (e.g., Who is the right target – initiators, gatekeepers, influencers, deciders, buyers and users). Marketers must be especially aware of cultural differences and how they influence the buying process (Example 6-3).

Channel Considerations

Customers receive information through all types of channels. Communication channels are frequently divided into personal and non-personal channels. The other important division, commercial and noncommercial channels, is based on control of the marketer, and is sometimes referred to as formal and informal channels. It is the challenge of the marketer to manage or control marketing information through these channels.

Example 6-3: The Impacts of Culture on Business Transactions

Latin America

When doing business in other countries it must be remembered that cultural differences are sometimes subtle, sometimes very apparent, but always important and key for the success of any international venture. For example:

- Even though all over the world a personal relationship between buyer and seller is key, customer loyalty differs widely among countries and regions. It may sound surprising, but US customers are among the least loyal of all the regions. One issue that hints at this characteristic is that in the USA it is common that buyer-seller relations are over the phone only (they have never met in person) – even if the business relation has gone on for years. On the contrary, Latin American and European relations tend to be closer, with buyer and seller visiting each other quite often (and distances are not smaller than in the USA!). In these later cases, relationships are typically stronger, which allows to ride the ups and downs of the markets quite better.

- For some countries, tradition and longevity in the market are crucial. In the middle of a product offering between a Latin American producer and a UK customer, the latter mentioned that his company existed before the foundation of the Latin American countries. This argument intended to support his need for a certain product in a certain fashion and not another.

- Terms of payment differ among countries and regions. North and South American wood products companies typically do not dare to sell into Asia with anything but a Letter of Credit (LC). This is true even though those same companies do not like LCs, as they involve banks and documents, where small mistakes or discrepancies may cause payment delays or even not payment at all. Strong cultural differences and sometimes a language barrier (customer or supplier visits involving a translator) explain this behavior. On the other hand, those same companies are willing to sell on CAD terms or even offer credit to companies in North America, South America or Europe. (Ernesto Wagner, General Manager, Santiago Chile)

Middle East

In Iran and the Middle East region, decisions for selection of materials for single-family homes, such as furniture, floorings, etc. are mainly made by the wife, while husbands are mostly controlling costs. If the family has young girls, these young and new generation girls are acting in their mother’s role in many cases, for decision making. Of course, in middle and high class families, decisions are made collaboratively but the role of wife and children of the family is much more than husbands.

In Iran and some countries of the Persian Gulf region, within high level and rich families, individual designers or designing offices/companies are highly influencing decisions for selecting home furnishing material and furniture. This is also the case for private offices. In poor families and in urban areas, the decision maker is only the husband.

In industrial purchase decisions, if the purchasing company is private, normally the decision maker is the owner/manager or one person on behalf of the owner. For example, for purchasing raw material for a furniture producing company, the seller may discuss with employees inside the buyer company, but the owner of the company is the final decision maker, especially for big purchases. In government organizations and some (very limited number of) private companies, decision makers are a group of employees that follow complicated purchasing regulations. Working with such companies is difficult for sellers and marketers. In such cases, normally one member of the decision making group has more power or effecting role on other group members. Marketers normally try to find this person. (Amin Arian, Industry Manager, Tehran, Iran)

The choice of channel depends on characteristics of the receiver but also the sender, the message, and the communication objective(s). Customers are selective as to the sources and channels they use for information acquisition. This selectivity has both psychological and sociological backgrounds. Customer communication behavior is not accidental or random but a result of experiences and lifelong learning. Generally, selectivity is based on needs and the receiver concentrates on those sources or channels that have historically been helpful. On the other hand, communication behavior has social roots. An individual’s exposure to communication is a direct result of what can be called their communication behavior. This means that different groups of people have unique tendencies regarding sources and use of information. This idea should be well understood by the marketer.

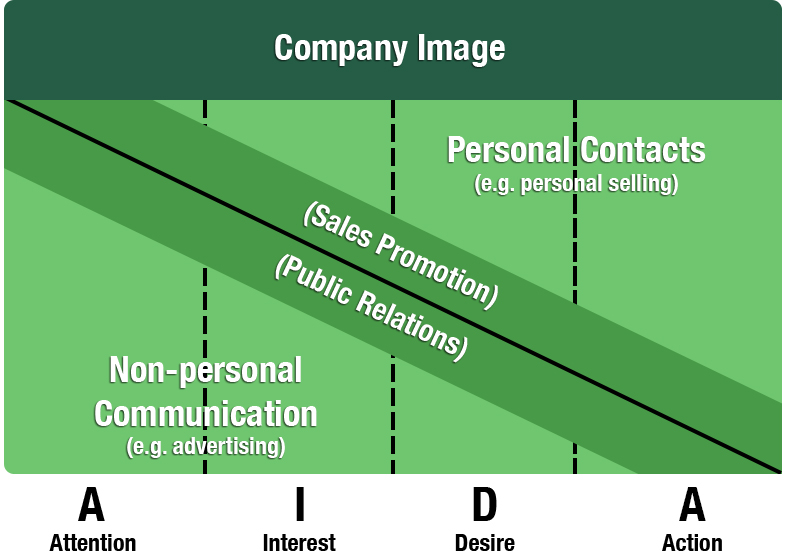

Although the final objective of most marketing communication is increasing demand by influencing purchasing decisions, there are other types of communication objectives as well, such as enhancing company image. Generally, the marketing objective is to take the receiver through a process from awareness to purchase. Different models of this process have been developed, the most basic of which is the AIDA model that describes the process in terms of Attention, Interest, Desire, and Action.[3] Different forms of communication are appropriate for various steps in the process.

Figure 6-2 illustrates the connection between forms of communication and response steps. Advertising, for example, is commonly used in an attempt to create awareness, while personal selling is more appropriate for later steps in the process. Communication which conveys a positive company image pervades the entire process.

As this text is written, the Internet is dramatically changing the communications channels utilized by forest industry companies. Companies are experimenting with social media. As electronic communication continues to evolve, the future may mean that we speak of the Internet as a communication “space” rather than a communication “channel”. While we can’t predict how communication via the Internet will look in the future, we can say with confidence that it will be different than what we see today.

Message Considerations

Message content must be directly connected to customer needs. Only information with value to the receiver is effective. Information must benefit the customer and satisfy some need – be it economic, psychological, or social. For instance, reducing economic risk is a typical customer need, which might lead to a quest for information.

The content and form of a message are complicated issues without absolute rules. Messages are often created by a communications specialist in an advertising agency. The following lists some basic requirements for an effective message in marketing communication:

- The message must fit communication objectives and the chosen marketing strategies behind them.

- A sender must have credibility with the receiver before a message will be received and absorbed.

- The receiver must be exposed to the message and must notice it.

- The message must be designed to meet the emotional and intellectual capabilities of the receiver.

- The receiver must be ready and willing to accept the message; it must be compatible with receiver and attitudes.

- The receiver must have a need for the content of the message.

6.2 The Communications Portfolio in the Forest Industry

Companies maintain a communications portfolio that is used to relay messages to a variety of stakeholders. Generally this portfolio will include the following types of communication:

- Personal selling

- Advertising

- Public relations

- Sales promotion

- Direct marketing communication

Although, personal selling is the most utilized type of marketing communication in the forest industry, advertising is the most visible part of marketing – so visible, in fact, that some people think that marketing is nothing but advertising. Although advertising and other forms of marketing communication are integral parts of strategic marketing, the work of advertising is generally outsourced to an advertising agency. Cooperation between a company and its advertising agency, however, must be close, in order to avoid communicating a disconnected message.

An agency can assist in managing the communications portfolio considering both the overall marketing strategies of the firm as well as specific communication objectives. The whole package must be integrated and well-balanced in order to achieve the stated objectives. Suppose a hardwood plywood firm developed a new panel using formaldehyde free adhesive, this major new initiative would necessitate an integrated introduction with the company’s communications efforts. The target audience and objectives for the communication efforts would come from the marketing strategies developed for the new product. The panels are targeted to North American architects designing high-end, LEED certified (green building standard) commercial projects. The primary objective is to create 50% awareness in the first six months of the campaign. The following are the planned actions and activities:

- Print ads will be placed in journals such as Green Building & Design and Construction and Architectural Record.

- Product brochures will be created that provide an overview of the product, its specifications, its environmental attributes, and face veneer options.

- Product samples will be sent to all qualified customers, distributors, and architects.

- The company Web site will provide:

- Links from the main page to additional pages which highlight the product

- On-line product training for salespeople and intermediaries

- Press releases will be created for both the popular and trade press and will be shared through social media.

- Introduction will coincide with the annual convention of the American Institute of Architects.

- Salespeople will introduce the product just prior to the show and begin actively selling after the show. Customers will be referred to the company Web site, and product brochures will be distributed on personal visits.

The plan outlined above integrates the various forms of communication and links appropriately back to the company’s overall marketing strategies.

Much of the communication conducted by companies is directed toward customers and potential customers. In this case the communication is most often about specific products or services. However, some communication is likely targeted toward other stakeholders than direct customers. News about new products may be especially relevant for investors (i.e., Wall Street). Developments in environmental performance may be relevant for investors, regulators, community members, NGOs, and customers. The point is that the communication portfolio should address all relevant stakeholders.

Of course, there is often direct personal communication with stakeholders on a regular basis as well. Although all stakeholders are important, customers are the key audience for marketing communication. In the forest industry, personal contacts have always been the most important part of the communication portfolio. Because of the importance placed on personal selling we speak of personal contacts and “other marketing communication” as the two major components of the communication portfolio.

6.2.1 Personal Contacts

The forest industry relies heavily on personal contacts with the customer, but tends to work closely with industrial customers rather than end-users. This means that their customers are typically large volume buyers and that they do not have large numbers of customers. In addition, a small number of big customers likely account for a large percentage of sales. In this setting personal selling is the most efficient means through which to market or promote a product. Although we speak here predominantly of personal selling, personal contacts includes a variety of relationship building or maintaining activities that occur between buyer and seller. Playing golf and going fishing with a client are good examples of relationship building activities that are part of personal contacts.

As mentioned in Chapter 5, companies have been changing their organizational structures in order to become more customer-focused. In larger firms, the role of the salesperson is changing toward dealing primarily with a few large customers. Even in smaller companies the interaction between salesperson and client is where relationship marketing really takes shape. When dealing with the same company and buyers over years, it is natural that friendships and relationships develop.

Salespeople should understand who their customers serve and what production processes they use. This knowledge allows the salesperson to help trouble-shoot production problems at the customer’s site, and perhaps even help the buyer specify different products/grades that will better fit their needs. As the customer develops new products, the salesperson can make sure the customer designs the product in such a way that raw materials/components can be feasibly produced by the supplier. This is just one aspect of the large role the salesperson plays in taking market information and market demand back to the production unit. In many ways the salesperson becomes a consultant to the customer (Example 6-4).

Example 6-4: Typical Sales Positions in the North American Forest Industry

Sales positions can be categorized in a variety of ways. For example:

Sales assistant – Sales assistants support the work of inside or outside salespeople, taking care of most of the paperwork for the salesperson that is interacting directly with customers. They typically spend most of the time in the office and interact with customers only via phone/fax/internet.

Inside sales – Inside salespeople typically do very little traveling and conduct their business primarily through the phone/fax/internet. In some situations inside salespeople can be described as order-takers and their main role is caring for routine, repeat purchases. This could be the situation for a long-established mill producing commodity products. Wholesalers are companies made up almost entirely of inside salespeople, usually referred to as traders. Traders typically work on large sales floors (open rooms with many desks where the salespeople can see each other) and may do both buying and selling.

Outside sales – Outside salespeople have the traditional role of the traveling salesperson, and most likely have responsibility for a designated geographical territory. Regular customers are visited on a consistent basis, and prospective customers are typically contacted as well. Travel is a significant part of the job and some people find themselves away from home more than half the time. Time in the office is typically spent catching up with paperwork and arranging the next week’s travel.

Strategic account management – Strategic account managers are different than traditional salespeople in that they typically deal closely with one or a few large customers. Close interaction means that these individuals spend most of their time in a support role rather than a traditional sales role. Essentially they become part of the customer’s team, helping the customer to succeed with the products supplied by his/her company.

Technical sales representatives – For some products, the salesperson takes on the role of a technical support person. For example, glue/resin companies have salespeople with a strong technical background. Their primary role is not so much to generate sales as to be a problem solver for the customer. Equipment manufacturers that supply the forest industry typically are organized this way as well.

Although the role of the salesperson is changing, cold calls (phone calls to unknown potential customers), trade shows, and golf games are still part of a typical salesperson’s life. The roles and responsibilities of a salesperson vary and include such aspects as:

- Increasing revenue

- Attracting new customers

- Retaining current customers

- Analyzing the competition

- Market analysis

- Coordinating sales activities

- Working with manufacturing locations[4]

Given these roles, it should be apparent that salespeople are the eyes and ears of the company in the marketplace. Salespeople possess a vast array of market, customer, and competitor information that should be incorporated into company knowledge management systems.

Personal Selling

Although personal selling – where a sales negotiation process containing a clear beginning and closing and viewed as a short-term transaction takes place – is rare in forest product marketing, it is nevertheless important to examine. Sales negotiation skills and other capabilities required in the selling process are important for forest product marketers.

The Selling Process

The sales process has been studied extensively. Although several specialized approaches have been developed, the sales process can essentially be reduced to the following sequence:

- Prospecting and qualifying

- The opening

- Need and problem identification

- Presentation and demonstration

- Dealing with objections

- Closing the sale

- Follow-up

The negotiation stage is often seen as taking place between dealing with objections and closing the sale.[5],[6]

Prospecting and qualifying is a process of identifying potential customers and evaluating their interest and financial health. Potential customers can come from a wide variety of sources ranging from the internet to commercial industry directories. Qualifying information can come from credit rating agencies such as Blue Book Online Services.

The opening or introduction should be designed to assure that the salesperson gets off on the right foot with the potential customer, and includes important details such as the appearance and timeliness of the salesperson, how they introduce themselves, and how they present their reason for setting up an appointment.

A good salesperson understands the art of listening. Need and problem identification is about listening to the prospective customer and learning exactly what their needs are in order to assess the product’s ability to meet those needs. By listening closely, the salesperson can formulate the appropriate approach to meeting both the expressed and latent needs of the customer.

After developing a good understanding of the need or problem that the customer faces, the salesperson typically has a chance to present and/or demonstrate their product or service. This is the chance to show the benefits the supplier can offer that directly address the needs of the potential customer. This might take place one-on-one or in a formal presentation. Public speaking skills can be a valuable asset for salespeople.

Objections are statements or questions from the prospect such as “it’s too expensive,” “I’m not ready to buy yet,” or “The last time I used your company I had problems.” In some ways these questions are signals from the prospect that they want more information. A salesperson should be prepared for objections and have a strategy for dealing with them. With experience, the salesperson will be able to anticipate most objections and develop an appropriate approach for dealing with the objections depending on the type of customer they are dealing with.[7]

Closing the sale is about asking the prospect for the order. Different strategies and tactics have been developed to help salespeople be more successful in closing a sale.[8] Each salesperson develops their own approach that works for them. Again, the approach may be different depending on the type of customer that is being targeted.

Follow-up can be as simple as calling the customer to make sure that the product arrived on time and in good condition. A salesperson may also follow the use of the product in order to anticipate future needs and orders. More extensive follow-up can be part of a customer service program, discussed in detail below.

While some derivation of the above process can be found in most personal selling textbooks, the process is becoming less applicable over time. There clearly are times when the model holds true, especially in commodity markets where salespeople are prospecting for new clients. However, for more advanced marketing settings where special or custom-made product strategies are used, the salesperson’s role is focused on developing a relationship, rather than following the traditional stages described above. For instance, the salesperson might be responsible for involving the client in joint product development projects.

As the role of the salesperson changes, companies are seeking different characteristics in industrial salespeople. Research indicates that critical thinking, reasoning skills, and communication skills (oral and written) are critical characteristics in the new sales environment. Companies also see ongoing or emerging trends that will require salespeople to be able to work with vast amounts of information, solve problems for the customer, maintain long-term partnerships with customers, and embrace change readily.[9] It is clear that modern sales jobs are becoming highly skilled positions in which personal selling is only one component.

Salespeople have a potentially significant role in marketing planning. As the eyes and ears of the company, they have the best insight into the wants and needs of the customer, which allows them to make an important contribution to marketing strategies and structures. For example, a salesperson might be the most likely member of the company to see opportunities for the development of specialty or custom-made products. Salespeople will also likely have an intimate knowledge of the competition, and the company’s competitive advantage in the market place. They might have perspective on where the company is vulnerable and upon which core competencies it can best compete. Unfortunately, companies often fail to take full advantage of the knowledge and expertise of the sales force.

Personal Contacts as Relationships

At its essence, the job of a salesperson is to initiate and maintain strong and productive business relationships with clients. In many cases these business relationships also become personal friendships. These ties between individual buyers and sellers can have a dramatic impact on the success of a company. It is easy to see why personal contacts can be considered from a relationship point of view. In practice, personal contacts are where relationship marketing is implemented. In today’s marketplace, relationship building and relationship maintenance is fast becoming synonymous with strategic account management. Companies are prioritizing their key customers and assigning additional resources to those strategic accounts. This may mean that a salesperson is dealing with fewer and fewer customers, but that those they deal with are critical to the company.

6.2.2 Other Marketing Communication

Advertising

Advertising is paid non-personal presentation and promotion of ideas, goods, or services.[10] For the purposes of our discussion, advertising can happen via radio, television, online, and print, but also includes tools such as product brochures, catalogs, and postcards. Although we use several categories of “other marketing communication” later in this textbook, some communication methods fall into more than one category. For example, brochures can be considered advertising and a form of direct marketing communication.

Advertising is generally a specialist’s task. The marketing manager/planner should be able to recognize a “good” ad and should have a clear understanding of the information needed by the advertising agency. Generally the marketer must have a solid understanding of the connections between the selected marketing strategies and structures and the message that should be communicated. With that understanding, it becomes clear what must be communicated to the advertising agency as it begins developing a communication plan or advertising campaign.

Advertising is most appropriate for creating awareness about the company or the company’s product. Hutt and Speh suggest that the following are appropriate objectives for advertising[11]:

- Creating awareness

- Providing information

- Influencing attitudes

- Reminding buyers of the company and product existence

Though television is not the main means of advertising for most of the forest industry, those that produce consumer products use television extensively. This advertising is almost always brand-based rather than company-based so consumers seldom associate the products with a forest industry company. For example, Kleenex brand comes from Kimberly Clark. Radio is used even less by the forest industry and when used it is nearly always in local markets.

Print advertising is very common among even the smallest forest industry companies, because placing ads in trade journals targets specific industry sectors and is therefore both efficient and economical. An MDF or particleboard manufacturer might advertise in Surface & Panel which targets industries using high-end decorative panels. Many trade journals are sent free of charge to their target audience, resulting in large circulation among perspective customers. These journals are sent to specifically qualified individuals who must provide information about themselves. Comprehensive information about its subscription base allows the journal to position itself as a valuable outlet for potential advertisers. Results of third-party circulation audits are generally available for trade journals. This allows the advertiser to more carefully select the appropriate outlet for the message.

Considerable research has been done regarding the content and appearance of print advertisements. Lohtia et al. identify ten criteria which can be used to identify successful business-to-business ads.[12]

- Has a high degree of visual magnetism

- Selects the right audience

- Invites the reader into the scene

- Promises a reward

- Backs up the promise

- Presents the selling proposition in a logical sequence

- Talks “person-to-person”

- Is easy to read

- Emphasizes the service, not the source

- Reflects the company character

Although most companies will have their advertisements created by outside experts, criteria such as these should be considered when evaluating proposed ads.

Product brochures are another form of advertising that is used extensively in the forest industry. Brochures are important because they can communicate technical information to end-users, such as construction companies. Engineering properties such as grade or strength can be captured in brochures to ensure proper use. Even those products that don’t need detailed supporting technical information usually have some form of promotional brochure. Product brochures are used in direct marketing communication as outlined below and by salespeople when making client visits, and extensively at trade shows.

Public Relations

Early in the 1900s, public relations was about creating publicity. Modern public relations, however, has evolved toward managing relationships with all stakeholders.[13] Some feel that public relations is about helping the company and its stakeholders adapt to each other.[14] The following are common forms of PR:

Press releases – used to announce introduction of new products, announce changes in personnel, or any number of important company events or developments. Press releases are used extensively for informing the investment community of financial results.

Trade journals and books – often used to profile the special expertise of a company. Trade journals are continuously searching for good stories. It may not be difficult to convince the Editor to write a story about process improvements at a company mill or some other significant development. The key from the Editor’s perspective is that the development be of interest to the journal’s readership. Companies can also benefit when employees publish articles in trade journals and scientific magazines. Having their employees recognized as experts in their fields enhances perceptions of the company’s inherent expertise. Companies often encourage this activity among employees, especially those in research and development positions. Companies sometimes even publish books written by their employees. For example, Columbia Forest Products published a book titled A Hardwood Plywood Manual.[15] The book is designed to be an indispensable reference book for companies using hardwood plywood.

Conferences – are a forum for current industry issues. Industry members are often asked to speak at conferences and by offering their knowledge and expertise to the audience they are in turn providing important exposure for the company.

Sponsorships – companies sponsor athletic teams, community events, and a wide range of other activities. The sponsorship requires financial support from the company and an indirect benefit is being acknowledged as a sponsor of the team or event. Roseburg Forest Products is a significant sponsor of Oregon State University athletics.

Sales Promotion

In consumer markets, typical sales promotion tools include coupons, rebates and contests. Since most forest industry companies operate in a B2B environment, these tools are relatively uncommon. The most common sales promotion tool seen in the industry is the trade show. Companies invest significant time, effort, and money to create an innovative booth that will attract attendees. In larger companies one or more people at corporate headquarters may be responsible for booth design and set-up at various shows, and in smaller companies, salespeople will hold this responsibility.

The timing and venue for trade shows are known well in advance. During annual planning, companies typically identify and budget for the trade shows they plan to exhibit in during that year. See Example 6-5 for an overview of important global forest industry trade shows. Typically, companies go to the same shows on a continuing basis. In fact, once they establish their presence at a show, customers expect to see them and their absence might create questions in their customers’ minds. For larger companies, national or international shows will likely be planned at the corporate level while regional shows will be planned at the division or even mill level.

Example 6-5: Major Forest Industry Trade Shows

Sponsored by the National Association of Homebuilders, this show is held annually and is the largest annual construction industry show in United States. Accompanying the show is a broad offering of educational programs targeting homebuilders and affiliated industries. In 2018, attendance was over 60,000 from 100 countries with approximately 1500 exhibitors covering around 53,000 square meters

Japan Home and Building Show is largest show related to the home and building industry in Japan. The show claims nearly 40,000 participants and over 500 exhibitors.

Interzum is a major trade fair for the furniture and wood interiors industries held in Köln, Germany every two years. Typically the fair consists of around 69,000 visitors and over 1,700 exhibitors covering approximately 180,000 square meters.

The design and production of a trade show booth is a critical part of planning for a trade show. It is important to plan for the show with specific objectives in mind. Objectives might include the following:

- Direct sales at the show

- New product introduction

- Identify new prospects/generate sales leads

- Meet with existing customers

- Enhance corporate image

- Assess competition[16]

As we noted earlier, trade shows are one communication method which should be carefully integrated with other communications efforts. Accordingly, a variety of methods should be used to announce to customers and potential customers that the company will be at the show and where they can be found. This is often done through print advertising in magazines that have special “show” issues. Postcards are often used to notify contacts of the details of a tradeshow, and social media is actively employed. In some cases, show organizers provide lists of registered attendees, which are used to mail promotional materials prior to the show. The final steps of trade show exhibition occur after returning home: evaluation and follow-up. A significant number of leads should have been gathered at the exhibit. These have no value if the individuals are not contacted; thus, these potential customers should be contacted to assess potential for future business. Each show should be evaluated based on the return on time and money invested. Exhibiting at a trade show is an expensive venture and success should be carefully weighed against the objectives established prior to the show.

Although there is often little actual business conducted during a trade show, it is an important event for salespeople in a company. The following are some of the most important aspects of a trade show:

- Likely the most important customers for the company will be in attendance. With this in mind, companies often plan separate functions for these customers, this might include formal business meetings and informal social events like receptions, dinners, and other entertainment. Trade shows should be viewed as an opportunity to build customer relationships. Salespeople are the heart of this endeavor.

- Trade shows attract a wide range of attendees and potential customers. Salespeople are responsible for running the booth and interacting with as many potential customers as possible. Usually, companies have some sort of gifts to give away and salespeople use these to attract people to the booth.

- Having a booth at a trade show is also about portraying and promoting the company’s image. Customers expect to see their suppliers at major shows and if a supplier is absent they will question the commitment of their supplier to that marketplace. In this respect, simply having a presence at major shows is important for maintaining company image.

- Tradeshows are one of the few times when major competitors will be concentrated in one location and will be showing off their best products and services. This is a great opportunity to learn more about their offerings, as well as their strengths and weaknesses. Although this aspect of tradeshows is often overlooked, it is a significant opportunity for salespeople to improve their knowledge and value to their customers.

Direct Marketing Communication

Many forms of communication can be sent directly to the customer or potential customer via mail, fax, or email. The product brochures discussed above are a common example. Other potential direct items include catalogs, price lists, product samples, postcards, and customer magazines or newsletters.

6.2.3 Organization of Communication in the Forest Industry

There are many common interests among companies in the forest sector which present opportunities for collaboration. Sector, and industry, level associations have been founded to capitalize on these opportunities, and to facilitate cooperation on tasks, projects, or publicity campaigns. Communication is clearly critical in this type of cooperation. Although most marketing communication is done by individual companies, there is considerable opportunity for synergistic communication campaigns. Promoting sustainable forestry, increased use of wood, or enhancing the image of wood as environmentally friendly material are examples of possible collaborative campaigns.

Shared campaigns dealing with topics of mutual interest have been launched in order to pool resources and make an impact on markets. Forest sector-level campaigns act as an umbrella for industry and company level campaigns which, in turn, act as an umbrella for company-level campaigns. Planning each level in a cooperative setting could create a remarkable synergistic effect. Sustainability, renewability and recyclability might be common themes for all levels.

Forest Sector Level Communication

Countries and national organizations often communicate with a wide range of stakeholders regarding the importance and environmental performance in the field of forestry. Here we speak of very broad efforts to promote the entire forest sector. Forest certification is a recent example of communications activity on a forest sector level. Various countries developed their own systems of forest certification and other systems have been developed on a regional basis. In each case the systems developed by forest industry and/or forest owners have as a primary goal improved communication regarding the sustainability of forest management practices. To communicate their message to various stakeholders, certification systems maintain Web sites and newsletters. However, from a marketing communication perspective, the most important element of their communication efforts is labeling of certified products. These ecolabels are what the potential customer or consumer see on the product. Wood. Naturally Better™ from Australia is a good example of this level of communication.

Forest Industry Level Communication

A bit narrower context for communication is the forest industry itself. Here communication is typically centered on industry sectors, such as building products. Companies maintain membership in groups, such as associations that play a critical role in promotion of the industry, its companies, and its products. Industry associations often take on the role of developing generic technical brochures for various product classes. Many associations have technical staff available to answer questions from professional users as well as from the general public. Other organizations have been formed to address critical issues faced by the industry. WoodWorks™ is a good example of this level of communication.

Company Level Communication

Most of the chapter thus far has discussed communication on a company-level, so we will only add here that companies should try to exploit opportunities for synergy with any forest sector level and industry level efforts.

6.3 Customer Support

Customer support is often difficult to separate from other marketing activities. For example, when a paper company develops a new, more efficient transportation solution, the development might be seen as customer support (if it creates benefits for the customer’s business), even though it is also part of the paper company’s internal development process. Furthermore, customer support and customer service are often used interchangeably, which may lead to confusion with terminology.

6.3.1 Need for Customer Support

In its most basic sense, customer support creates value for the customer. When a company improves its customer support, it often serves to streamline its own business processes. Making business processes quicker and less labour intensive has positive implications for both the buyer and seller.

Customer support adds an important dimension to the physical product by adding value for the customer and thereby differentiating the product from its competition (particularly important with commodity-based products). By providing superior customer support or offering unique service, the company not only differentiates itself, but also strengthens the customer relationship, and creates a competitive advantage. This reduces the likelihood that the customer will change suppliers and may even reduce price sensitivity.

The nature of customer support changes with developments in both the internal and external environment. Current developments in the external environment which are having a significant impact on customer support include:

- Developing information technologies

- Intensifying competition

- Developing distribution systems

The shift from the age of fax and telephone to the Internet and e-mail creates possibilities as well as new challenges. The ability to efficiently seek and distribute information in real time enables companies to create new types of support for their customers based on automated data transfer or on-line information. It is possible to create added value for customers by enabling them to seek the needed information themselves through a service provided by the supplier. The company can enhance both the efficiency and the perceived value of the service, especially in routine transactions like tracking deliveries, with no need for personal interaction.

E-commerce can also lead to unexpected problems. When a customer can easily contact multiple suppliers or even automatically search offers from their suppliers, the likelihood that a customer switches suppliers may increase. Consequently, companies must make a more concerted effort to foster customer relationships, maintain personal interaction, and understand customer needs. While new technologies allow a company to make basic customer support more efficient, it also poses challenges that can only be met by more traditional, personal service.

As competition becomes more intense, companies must focus on their competitive advantages in order to defend their market share. The production technologies and raw materials used for forest industry products are essentially available to anyone. Thus, access to technology is seldom a competitive advantage. Instead, the total product must be differentiated by providing customers with superior services. Customer support can serve to convert a commodity product into a custom-made product. By offering a tailor-made service for the customer, such as special delivery arrangements, the product will be suitable (and preferable) for a specific customer. This means that customer support can be a critically important part of a company’s marketing functions.

6.3.2 Strategic Importance of Customer Support

Customer Support Connected to Product and Customer Strategies

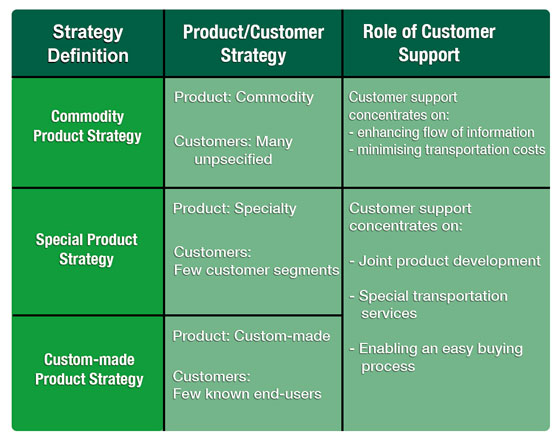

Decisions made about product strategy have implications for a suitable customer strategy, and the reverse is also true. Chosen strategies affect the forms of customer support that should be developed. The relationship between product and customer strategies and their implications for customer support are considered in Figure 6-3.

If a company pursues a commodity product strategy, it most likely sells to many unspecified customers. The main customers may be wholesalers, importers, and other large volume buyers. In this case, customer support should be concentrated on making functional communication between the buyer and seller as efficient as possible. This means enhancing the flow of information and documents especially regarding shipments, specifications, and invoices. With large customers, an important goal of customer support is to minimize transaction costs. The ordering and delivery of goods must create minimum effort (and cost) for the customer. One way to improve the flow of information during the business process and reduce costs.

Customer support should also serve to minimize the cost of transportation, creating a benefit for both the buyer and the seller. The flexibility a company has in arranging transportation is dependent upon the demands of the customer. If a customer demands JIT delivery, there may be very little flexibility.

However, other customers may care less about delivery time and more about transportation costs. For example, importers generally place a higher priority on minimizing transportation costs than on accuracy of delivery time. If a company can create low-cost alternatives for transportation by arranging special freight rates with shipping companies or by combining cargoes with other producers, significant benefits may be created for the customer.

Although customer support is vitally important, most companies are limited in the amount of resources they can dedicate to it. If the customer base is wide and unspecified, the company should focus its resources on making the support as widely appealing as possible and try to automate routine activities and serve all customers with a single system.

Customers who demand special and custom-made products are usually industrial end-users. Meeting special demands requires a concentration on specific services targeted to each customer segment or even to an individual customer. Because industrial end-users generally use very few or only one type of product, requiring the supplier to adapt its product to its needs, customer support in the form of joint product development projects is especially important. Special delivery options may also be critical for industrial end-users.

Industrial end-users often have no dedicated purchasing manager, so the buyer in these organizations is generally trying to minimize this effort. The supplier should make the purchasing process as easy as possible. Customer support in this case is bound to be on a very personal level. The supplier must provide the buyer with technical information about product properties, understand the buyer’s business process, make suggestions about suitable products, and place resources into developing such products and delivery arrangements that create the most benefit for the customer.

For many industrial end-users, the timing of delivery is more important than minimizing transportation costs. Precise delivery times are necessary in order to adequately meet the needs of their production process, while maintaining low inventory. The supplier must concentrate on identifying transportation solutions that are reliable and fast, with minimal risk of delay. This usually means the supplier maintains warehoused inventory ready for immediate shipment.

6.3.3 Customer Support in Practice

Pre-Sales Customer Support

Pre-sales customer support is important for initiating or maintaining a business relationship. By giving a high level of support at this stage, the company can ensure the realization of new business opportunities and strengthen the relationship with the customer. The most important forms of pre-sales customer support include:

- Joint product development

- Technical product support

- Logistics support

- Training

- Communicating production and delivery possibilities

Product development is typically (especially in the mechanical forest industry) conducted in cooperation with the customer. Because the needs of industrial end-users vary greatly, there is a higher demand for product adaptation. Product development in the sawmilling industry concentrates on the optimization of grading (e.g., defining the number and size of knots, amount of wane and heartwood content), developing special lengths or dimensions for the sawn timber pieces, and creating new sawing techniques (e.g., special heart free cutting). In the paper industry, joint product development may mean arranging test runs for different grades of paper on the buyer’s printing line and subsequent adjustments to the composition of the paper. Technical product support is designed to inform customers about technical product characteristics. The customer is able to better plan her own activities when possessing good knowledge of the available product range.

To provide effective technical support the seller must understand both her own products and the production processes of the customer. The technical capacity and limitations of the customer’s production line, and the requirements placed on the end product, produce the framework for finding an optimal solution. With the right knowledge, the supplier is able to make proposals about cost effective, functional solutions.

Often, even before making a sale, the supplier must advise the customer about the most efficient methods of transportation. Warehousing near the customer and finding ways to provide smaller deliveries with increased frequency might be important services for many industrial end-users.

In further processed products, training may be an important form of customer support. Particularly in the case of introducing products with new features, the supplier must possess sufficient resources to communicate the vital features of the product to the customer. For example, when introducing a new paper grade, it is critically important to train the paper wholesalers so they understand the characteristics of the paper and its best uses.

In the mechanical forest industry, an especially important form of customer support is keeping customers updated on current stock availabilities and production possibilities. This information can be given by sending the customers a stock note indicating free items and by advising them regarding short-term production plans. Because transportation may not be available for rapid delivery, it is also important for the customer to know which delivery possibilities exist at a given time and when the goods can potentially be delivered to their final destination.

Post-Sales Customer Support

Signing a contract with the customer means delivering the right products in good condition and at the right time. Typically customer support in the production and delivery phase comes in the following forms:

- Providing information about the stage of production and delivery

- Making changes to order contents and delivery details

- Following-up on delivered goods

- Handling claims

Because of variation in production and transportation, it is often difficult to determine an exact delivery date at the time that the contract is signed. Water transportation can be especially problematic in predicting a precise delivery date. Because industrial end-users depend on accurate information about incoming deliveries, the supplier must keep the buyer abreast of all changes and delays, even those caused by external factors. Changes in the buyer’s production can also require changes in the delivery schedule. Here the supplier must assist the buyer by allowing flexible deliveries. The customer may even need to change their order completely, such as the case of a furniture mill which suddenly requires a different timber dimension due to a rush order from a retailer. These kinds of requests become more common as the customer type changes from wholesalers to industrial end-users.

Online options can implemented for routine issues such as the following:

- Current order status

- Estimated or confirmed date of shipment and/or arrival

- Estimated or confirmed specification of goods to be loaded

- Follow-up of contract balances

- A variety of searches based on product data such as average quality or length specification of sawn goods or technical specification of paper grades

The supplier and the end-user must work together to monitor quality in order to maintain appropriate quality levels. Regular monitoring of delivered goods and their performance in further processing is needed. This adds both to the perceived credibility of the supplier and ensures that the buyer is receiving the appropriate product quality. If the product or the delivery process does not adhere to the standards set in the agreement, the customer has the right to make a claim. In the lumber industry, claims are usually about not meeting the agreed upon grade. Examples include too high moisture content, excessive number of knots, and bad quality of knots. Problems in the delivery process may also result in claims, for instance cargo may get wet during shipment or may have been stored improperly in the warehouse, impacting quality.

If a claim is received, the supplier must respond to it rapidly and amicably in order to preserve the customer relationship. The source of the problem must be identified, corrective actions taken to avoid new claims, and a settlement reached to ensure the buyer’s satisfaction. Compensation is often monetary, but can also consist of a replacement load or additional load. Use of digital pictures is customary for documenting claims.

When a claim exists, close interaction between production (or transportation) personnel and the buyer is required, so that all parties understand the reason for the problem. Many claims are the direct result of an insufficiently precise definition of the quality ordered by the buyer, particularly in cases which involve new customers. It is imperative that both parties understand the buyer’s needs and the supplier’s capabilities. A properly handled claim may not be the end of a relationship, but a foundation for stronger cooperation in the future.

6.4 Functional Communication in the Forest Industry

6.4.1 Functional Communication in Marketing

Functional communication refers to the routine flow of information through the marketing channel, including both verbal communication and documents necessary for business transactions. This process begins with an enquiry and ends with payment for delivered goods. A large part of the day-to-day business in the forest industry consists of repeat purchases and accompanying functional communication. When the buyer and the seller know each other and have defined mutually acceptable terms for business, repeating an order is very much a routine action. However, this does not diminish the importance of well-conducted functional communication; on the contrary, it makes this communication one of the key elements in providing good customer support. If a supplier does not reply promptly to enquiries, if the issuing of shipping documents is delayed, or if invoices regularly contain errors, the buyer’s business becomes less efficient. Unnecessary work is caused, time is wasted, and the supplier’s image deteriorates in the eyes of the customer.

Efficient flow of information within the company is as critical as that which is exchanged with customers. If the sales team does not inform the production manager about a projected delay in a customer order, significant economic losses may result due to excessive and spoiled stock.

6.5 Pricing

To understand pricing as a marketing tool, the difference between price and value must be recognized. Price is the amount of money that the supplier asks for a product or service and the amount which the customer provides. On the other hand, value is the amount of money the customer would potentially pay for that product or service. A price can be set without any consideration of the customer, but the value is defined by the customer. Value is based on the customer’s perception of the total product’s utility. The distinction between price and value is important. Pricing without consideration for value can result in a price that is so high that sales are lost or so low that revenue is lost. The only way to optimize price is to understand value from the customer’s perspective, which demands detailed customer knowledge.

The ability of a company to control price is partially dependent upon the characteristics of the product and the marketplace. In general, the price of commodity products (like construction lumber), is highly dependent upon the market. On the other hand, a very unique product can provide a company with significant control over price. The nature of the channel of distribution also has an impact on pricing flexibility. Short channels (i.e., near-direct sales) allow a company to price based on its own objectives. Longer channels with intermediaries require that decisions are based on the objectives of several channel members and the manufacturer must consider the needs of the channel members when it decides on its price. Trends in the marketplace, reactions of competitors, and changes in raw material supplies are all potential causes of change in established price. The dynamic nature of the setting in which companies strive to establish prices means that managers must carefully weigh what might happen as a result of pricing decisions, both in the short and long term. When creating a product’s price, the following questions should be considered:

- What is the value to the customer?

- What are the total costs of making and delivering the product to the customer?

- What influence will the distribution system have?

- How will direct competitors react to the price?

- Will the price need to be higher or lower in the future?

- How does the price fit into the overall scheme for discounts or allowances?

- How does the price fit with pricing of the product line?

Differentiation increases pricing freedom. A product that is more differentiated does a better job of meeting the needs (or wants) of its intended customers. Thus, the value of that product will be effectively maximized, and a higher value product supports a higher price. Nagle and Holden outline a number of factors that influence how price sensitive a customer might be. Those most relevant to the forest industry are[17]:

- Perceived substitutes effect – what alternatives does the customer recognize and how aware is he/she of the price of those alternatives? For a product like lumber, the customer is going to know very well what else is available in the market and what its price is. These alternatives make the customer more price-sensitive.

- Unique value effect – is the product truly unique and are the unique characteristics of value to the customer? Customers will be less price sensitive when the supplier offers a level of quality that makes their production process more efficient. A truss manufacturer may value one lumber supplier over another because she knows that the percentage of unusable pieces will be much lower.

- Switching cost effect – does switching from one supplier to another have accompanying expenses? A publisher that has a long time relationship with a paper producer may be hesitant to switch because of the investments it has made in the relationship. It would be expensive for the customer to establish new contacts and new routines so it will be slightly less price-sensitive.

- Difficult comparison effect – is it difficult for the customer to evaluate offers from other suppliers? Can a printer effectively evaluate the runability of a competitor’s offering without conducting a test run? If it is difficult to evaluate other possible products, the customer will be less price sensitive.

- Price-quality effect – sometimes price can be an indicator of quality. If the customer sees a higher price, will they associate it with higher quality or will they automatically reject it. This effect is more often associated with consumer goods, but also has some application in industrial products.

- Expenditure effect – how much does this product cost as a percentage of the customer’s final product? An alder lumber producer with two customers, a furniture manufacturer and a picture frame manufacturer, will find that the furniture manufacturer is more price-sensitive than the picture frame manufacturer. This is because the alder lumber represents a much larger proportion of the final value of furniture than of picture frames.

- Inventory effect – what inventory levels does the customer maintain and what do they expect about future price fluctuations? When the customer has low levels of inventory, he may be less price sensitive. In commodity sectors of the forest industry, prices fluctuate a great deal and intermediaries tend to be speculative If the customer expects prices to climb, he will be less price sensitive than if he expects them to fall.

6.5.1 Pricing Objectives and Methods

There are a number of objectives that a company may strive to achieve through its pricing decisions. A company may price to obtain short or long term profits, to increase market share, or simply to meet the price of the competition. While each of these objectives may be appropriate in a given situation, a company must consider how its pricing objectives fit with the overall marketing strategy. For instance, pricing may vary throughout the product cycle, depending on whether the company is trying to stimulate market growth or gain market share, or has achieved its target market level and is seeking to maximize returns.

Traditionally, prices have been developed by considering the costs of producing the product or service and then adding some level of profit to that value. However, pricing decisions should begin by assessing the need in the marketplace and the value of satisfying that need. Based on this information, the company can develop a product or service with a cost structure that will allow a price at that level of value. In other words, costs should be determined based on the possible price, not vice versa.[18] Cost-based methods have been used because they are relatively simple to apply. However, their major weakness is that they are dependent upon accurate cost accounting, information that is not readily available within many companies because of the complexity of assigning fixed costs across a product line.