Chapter 5: Marketing Structures

After reading Chapter 5 you should understand the following:

- The relationship between marketing strategies and marketing structures.

- The role of marketing structures in facilitating marketing functions.

- How business trends are changing the way companies are organized and how marketing is organized and implemented.

- The nature of trendy business concepts and how they relate to marketing.

- The role of information systems in marketing planning.

- The nature of marketing channels and how they function.

- How social relationships impact management of marketing channels.

Chapter 5 covers marketing structures—the element of the Integrated Model of Marketing Planning (IMMP) that falls between marketing strategies and marketing functions. Marketing structures are arranged in order to realize marketing strategies and to facilitate marketing functions. For example, if a company emphasizes product quality as a core competency in its marketing strategy, implementation of a total quality management system may be an appropriate approach to management.

Marketing structures include management and organizational structure as well as planning and information systems, and especially marketing channels. Marketing structures are created to facilitate marketing functions. In this chapter we discuss how business trends are impacting the way marketing is conducted. Customer relationship management, supply chain management, and planning and information systems are discussed and illustrated, and marketing channels are discussed with an emphasis on the marketing channel as a social system.

5.1 The Evolution of Marketing Management

General business management trends have a significant impact on the way marketing is managed and practiced. For example, moves toward lean thinking, total quality management, supply chain management, and customer relationship management all change in some way the manner in which marketing is conducted. These shifts in management practices have influenced the evolution of the marketing concept described in Chapter 2, and in turn the evolution of marketing management.

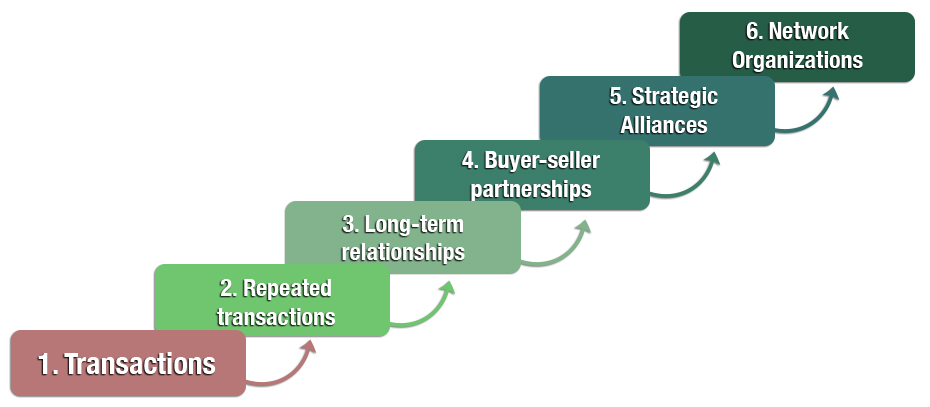

The evolution of marketing management can be described as a shift from viewing marketing as competition and discrete transactions to viewing it as cooperation and relationship building. Webster provides a comprehensive description of the range (seven categories) of marketing relationships and suggests that marketing is clearly moving from “arm’s-length transactions and traditional hierarchical, bureaucratic forms of organization toward more flexible types of partnerships, alliances, and networks.”[1] The most basic marketing relationship is the transaction, and the most comprehensive relationship is vertical integration, where a company owns its upstream suppliers and downstream channel members. The forms of relationships and the idea of marketing have changed, and therefore marketing management approaches must change accordingly. The following outlines the general concept of the six relationship categories (Figure 5-1).

Transactions – At this lowest level there is no relationship between buyer and seller. In this traditional microeconomic approach to a transaction, price contains the necessary information and marketing is expected only to find buyers. When a pure transaction takes place, it is a one-time event with no interaction between the buyer and seller either before or after the transaction, a rare situation in industrial marketing.

Repeated Transactions – A more realistic view of exchange is repeated transactions between a buyer and seller that result in the formation of a relationship (though likely still distant and weak). Marketing is expected to develop differentiation in order to create preference and loyalty that will result in higher prices and profits.

Long Term Relationships – Industrial marketing has typically been based on long-term relationships through contracts, but relationships were often arm’s length and adversarial. Competitive bidding for contracts was a common practice and multiple suppliers were maintained in order to remind the main supplier of competitive options. Increased competition and the need to cooperate have caused firms to move away from the adversarial model to partnerships and interdependence.

Buyer-Seller Partnerships (mutual total dependence) – Strong partnerships became common during the move toward quality management. Japanese manufacturers found that producing high quality products is not only more attractive to customers, but also costs less. To produce high quality products, those Japanese companies also found that partnering with a small number of suppliers was much more successful than the adversarial supply approach. The success of these Japanese companies has caused companies in other parts of the world to follow suit.

Strategic Alliances (including joint ventures) – The basic characteristic of a strategic alliance is an intention to achieve a strategic goal. The partners may be working toward the development of a new product, new market, or new technology. A joint venture is one form of strategic alliance where the partners create a new firm.

Business Networks – Webster uses the term “network organizations” to refer to multiple strategic alliances, but we use the term “business networks” to describe the myriad relationships that exist among modern companies.

The basic evolution described above provides a meaningful context for discussing a variety of concepts and tools that have accompanied the evolution. The following discussion covers the topics of relationship marketing, information technology (IT) in service of marketing management, and supply chain management. Finally, the interaction of these elements, and the potential impact on future marketing management practices, is outlined.

5.1.1 Relationship Marketing

Traditionally, the study of marketing has been based on the transaction. This is because of marketing’s historical ties to economics. In a theoretical, discrete transaction, the buyer and seller do not interact before or after the sale, and price is the determining factor in making the transaction occur. A one-time purchase by a retail lumber yard from a wholesaler as a result of a cold call is basically a discrete transaction, but these sorts of transactions are uncommon in industrial marketing.

If we think of transactions between the buyer and the seller as a continuum, discrete transactions are at one end and relational transactions are at the other. In relational transactions, there are long-term relationships and high levels of cooperation between the buyer and seller.

Prior to industrialization, the exchange of goods and services was primarily local and based on long-term relationships between small-scale producers and final consumers. As industrialization pervaded society, production-oriented organizations were forced to find ways to sell the large quantities of goods that new technologies allowed them to produce. This situation resulted in the formation of a transactional approach and aggressive selling through marketing intermediaries, a situation in which marketers were more focused on sales and promotion than on building customer relationships.[2]

The post-industrial era is much more relationship-oriented. Firms now recognize the value of repeat purchases and brand loyalty and the nature and complexity of true transaction costs.[3] Paying the lowest price is not always the best choice, because the supplier offering the lowest price might, for example, offer mediocre quality. Also, the process of finding suppliers and engaging in negotiation is costly. By relying on fewer, long-term suppliers, many transaction costs are minimized.

Rapid changes in technology and the competitive environment have forced companies to seek cooperative relationships.[4] Customer demand for quality and performance have increased to the point that firms often must cooperate in order to access the necessary expertise to satisfy those demands. Even though it is somewhat paradoxical, cooperating to compete is becoming essential in today’s global marketplace.[5]

So what is relationship marketing? It has been seen as a rebirth of marketing practices from the pre-industrial age where marketing activities help establish, develop, and maintain relational exchanges.[6],[7] Instead of competition, the direction of relationship marketing is cooperation. Models for effective relationships are sought from social psychological group theory which emphasizes cooperation and social values. In other words, successful, long-lasting business relationships are based on mutual commitment and trust.[8]

It is clear that the day-to-day practice of marketing involves increased cooperation, and evidence suggests the trend will continue (Example 5-1). This is not to say that strong relationships always exist between buyers and suppliers, or even that they should. In fact, companies should concentrate on key customers to develop strong relationships and invest less in minor customers.

Although fundamental aspects like cooperation instead of competition are emphasized here, we do not suggest that relationship marketing covers the whole area of marketing as it is defined in Chapter 2. Relationship marketing can be thought of as customer relationship management, which provides the principles and tools to establish, develop, and maintain successful business relationships. We emphasize that relationship marketing (customer relationship management) be seen in its strategic marketing context. As we will see later in this chapter, marketing strategies give direction to appropriate structures, including management systems.

In relationship marketing the primary idea is that the producer chooses the customers that best fit its resources. It is also important that the producer knows the value creation process of its customer. It is possible to develop value-added products and satisfying customer support if the relationships between producers and customers are close. This is the essence of relationship marketing.

Example 5-1: Great Recession Illustrates Importance of Relationships

The Great Recession decimated the North American forest industry, but its outcomes illustrate the importance of strong relationships – especially in tough times. Merchant Magazine interviewed lumber company managers in the western U.S. and concluded that relationships between mills and customers, “will take on even greater importance as sales start to recover” and that, “Many mill sales executives said fortifying those relationships are a priority.” Managers claimed that during the Recession they had been working to improve relationships by:

- Traveling more to meet customers

- Spending more time evaluating customer needs

- Fine-tuning product offerings

- Introduced new brands

- Becoming more flexible with long-standing customers

Merchant Magazine concludes by saying that buyers who stayed with mills through the difficult times of the Recession will be the ones that get supply when the market heats up. One manager was quoted as saying, “Our best customers are those who understand that we rise and fall together. Those are the people we want to do business with, in good times as well as bad.”[9]

5.1.2 Information Technologies in Marketing Management

Information technology (IT) covers a broad set of technologies used to document, process, utilize, and communicate information. The infrastructure allowing a company to do business and communicate with other companies can be called a commerce platform.[10] The commerce platform has changed dramatically in recent years. Prior to computers, the commerce platform was based on the telephone and paperwork maintained by a company. If, for example, a buyer and seller negotiated a deal over the phone, the seller would typically prepare a bundle of papers outlining the deal that would then be mailed to the seller for a signature. The buyer would sign and return papers by mail (Example 5-2).

The advent of the fax machine increased the speed of this process. It was no longer necessary to mail paperwork to be signed; it could simply be faxed between the buyer and seller. Computerization has had a dramatic impact on the daily work-life in every industry. For example, efficiency in order processing and other paperwork is greatly enhanced by eliminating the need for manual typewriting. Many other simple changes have also occurred. Traditionally, salespeople carried files documenting information about their various clients, but today nearly anything is available via smart phones.

Both internal and external business operations based on IT can be referred to as e-commerce. E-commerce allows a company to better organize and utilize resources through the effective use of information. E-commerce can result in a variety of benefits including cost savings, rationalization and automation of operations, and more efficient use of resources. Enterprise resource planning software allows all departments in the company to use the same system based on a common database. With this integrated structure, other e-commerce functions can be added to the company’s system (e.g., supply chain management or customer relationship management).

Example 5-2: Evolution of the Commerce Platform

In his 1970 textbook, Rich outlined the impact of Wide Area Telephone Service (WATS) on the marketing and distribution of wood products. At that point in time, WATS, which allowed a company to make unlimited calls within a certain geographical area for a fixed monthly charge, helped eliminate the practice of double wholesaling of West Coast lumber. Double wholesaling meant that local wholesalers in the West acted as finders of supply for local wholesalers in major Eastern markets. These Eastern wholesalers then resold the lumber in their market areas. The lower costs of communication meant a trend toward Western wholesalers dealing directly with players in the Eastern market areas, and Eastern wholesalers dealing directly with Western sawmills, thus eliminating one stage in the marketing channel.[11]

5.1.3 Supply Chain Management

Supply chain management (SCM) illustrates well the increased importance of strong and close business relationships, as well as the role of e-commerce in a company’s ability to manage its operations. Therefore, we have developed a deeper explanation of SCM as an illustration of a marketing structure. Supply chain management has its roots in logistics and is used in place of more traditional terms such as physical distribution. SCM has been defined as “the management of upstream and downstream relationships with suppliers and customers to deliver superior customer value at less cost to the supply chain as a whole”.[12] A well-functioning supply chain has been described as a highly-trained relay team where the strongest relationships exist between the two parties that exchange the baton, but the whole team must be well coordinated in order to win.[13]

The basic concept of supply chain management means taking a systems viewpoint. This means, for example, that firms participating in SCM are not looking only at minimizing costs in their own situation, but also minimizing costs for the entire system. It is a long-term approach with continuous joint planning and widespread sharing of information.[14]

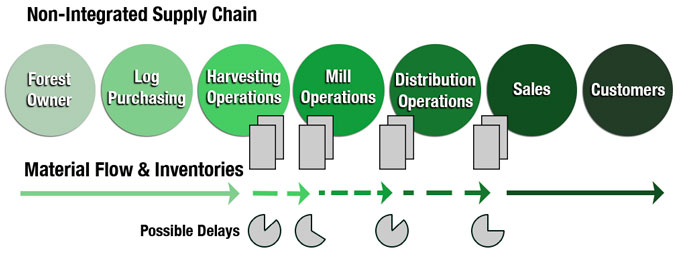

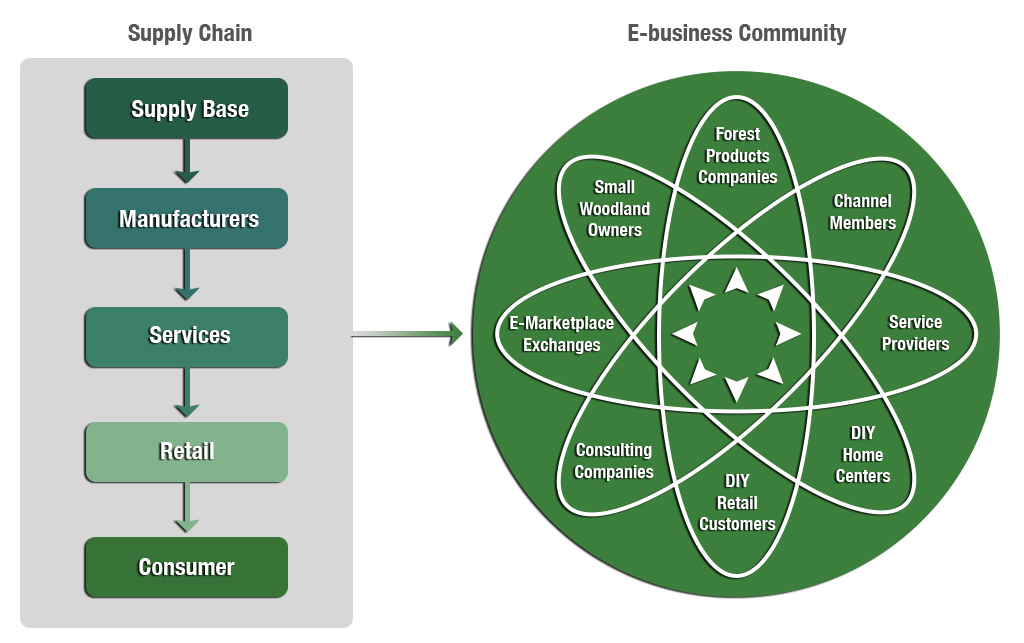

A supply chain can be viewed as shown in Figure 5-2. Between each member of the chain, and within any given member’s organization, there is the potential for time delays and excess inventory, both of which equate to costs. The buildup of excess inventory between members of the chain has been described as snowdrifts against a fence. The more members of the chain, the more snowdrifts and more inventory in the system.[15]

Through close cooperation and efficient flow of information up and down the chain, costs can be minimized. If real-time information regarding demand, forecasts, orders, inventory levels, etc., can be communicated back through the chain, members of the chain can provide just the product and volume needed at exactly the right time. Without this information flow (communication), members of the chain are operating based on only their individual information. This may cause them (for example) to maintain inventory levels high enough to cover unexpected orders and shifts in demand, and again, high inventory levels equate to costs.

The two key components of successfully implementing SCM are the development of strong and close relationships among members of the chain that allows their integration into a fully linked and functional supply chain.

SCM and Relationships

It is generally accepted that competition is moving away from company versus company and towards supply chain versus supply chain. A supply chain is made up of a variety of different channel members and these members must work closely together in order to bring about cost reductions and enhanced customer satisfaction. Accordingly, the quality of relationships among members is of paramount importance to successful implementation of SCM.[16]

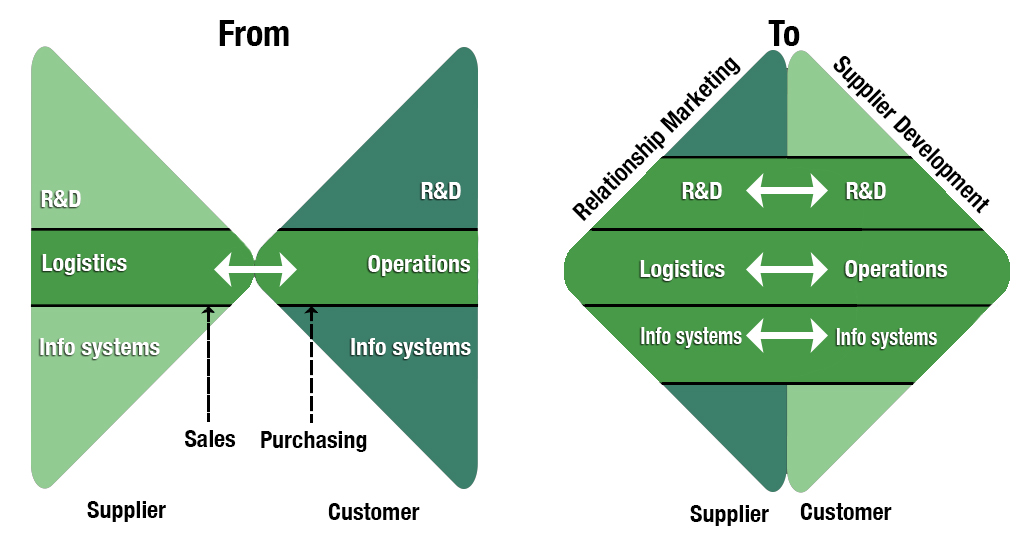

Looking at the link between two successive members of a supply chain (dyads), Figure 5-3 provides a view of how the interaction of two companies must change in order to create the strong relationship needed to implement SCM. The interaction must change from only between sales and purchasing towards integrated interaction at multiple levels of the organizations so that the interface allows rich communication and strong cooperation.

A high degree of cooperation must exist among all the supply chain members to effectively share the information and duties necessary to optimize the whole supply chain from raw material producer to final consumer. A level of trust must exist among the members of the supply chain so that they are comfortable sharing proprietary information. This level of cooperation means that joint planning will be commonplace and members are likely to collaborate in other areas such as new product development. It is also important to note that the performance of the supply chain is not only dependent upon the cooperation of the firm with its partners, but also upon the cooperation of those partners with their partners.[17] This leads to looking at the supply chain more as a network than as a chain, a concept further discussed below.

As in any relationship, when a firm commits to cooperation in a supply chain, it places itself at some risk. Examples of this risk include poor performance by other members of the chain, other members sharing trade secrets with competitors, or members venturing into the business on their own.[18]

SCM and Integration

As mentioned in Chapter 2, integration has always been a key role of marketing. As one in a series of marketing structures, SCM is a way to integrate both internal and external supply chains, and this integration is the cornerstone of excellence.[19] Integration must begin within the firm, but involves combining elements from inside and outside the company. Integration forces a company to consider management in a more holistic manner. Traditionally, companies have been organized along functional lines, a structure which leads managers to feel territorial and defensive about their individual areas. SCM, on the other hand, requires that these functions work more closely together.[20]

Christopher, M. 1998. Logistics and Supply Chain Management. Financial Times/Prentice Hall. London. 287 pp.

Close collaboration within a company may require a new form of business structure described as horizontal or market facing.[21] In this structure, multifunctional teams are organized around processes (e.g., customer management) rather than traditional functions such as production or sales. Multifunctional teams have the knowledge and understanding of the entire business to help minimize those costs and delays that occur between steps internal to the company.

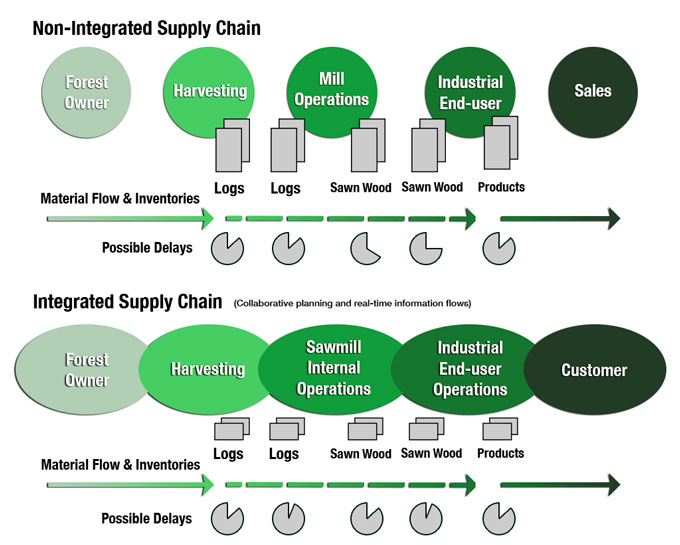

Once a company has succeeded in integrating its own operations, it can begin to consider integrating other channel members. Integration of channel members allows a firm to begin creating a truly linked supply chain with the ability to transfer information up and down the chain (Figure 5-4).

Evans and Danks suggest four forms of integration: information, decision, financial, and operational.[22]

Information Integration – enables companies in the supply chain to share useful information among themselves. For example, information sharing between producer and retailer can help in production scheduling and in maintaining stock. This could be especially important when just-in-time (JIT) delivery is required by the customer.

Decision Integration – allows the ability to manage planning and control functions across multiple firms. As in the team analogy, decisions are no longer made by individual firms within the supply chain, but instead are made jointly for the benefit of the whole.

Financial Integration – changes the payment terms and conditions across the supply chain. For example, a supplier might expect payment when the customer sells the product rather than when the customer buys the product.

Operational Integration – means sharing assets, both physical and human. A manufacturing company might supply office and floor space for a supplier within its own production facility so that it can better supply components or raw materials.

What is the difference between an integrated and a non-integrated supply chain? Figure 5-4 simply shows that in an integrated supply chain, the channel members are linked together as the word “chain” implies. Without integration, the channel members are independent links that do not benefit from close association with other members. This means that, for example, the likelihood of delays and excess inventory to exist between links is very high. As previously noted, a fully linked and functioning supply chain includes the efficient flow of information both up and down the chain.

Hill, T. 2000. Operations Management: Strategic Context and Managerial Analysis. MacMillan Press Ltd. Great Britain. 704 pp.

Results of Successful SCM

Researchers have found that appropriate SCM practices result in superior financial performance.[23] A number of benefits can result from supply chain collaboration, a situation where members of the supply chain actively work together as one to achieve common objectives such as the following[24]:

- Reduced inventory

- Improved customer service

- More efficient use of human resources

- Greater trust and interdependence

- Improved shareholder value

The basic goals of SCM, improved customer satisfaction at lower costs, are clearly evident in the items listed above. In the context of SCM, Coppe and Duffy outline the following potential benefits of the Internet.[25]

- More cooperative and timely product development resulting from enhanced communication among departments, suppliers, customers, and even regulatory agencies

- Reduction of total inventory in the supply chain through closer links across the supply chain and better knowledge of demand

- Lower communication and customer support costs

- New abilities to reach different customers and better exploit current markets

- Ability to enhance products and relationships through customization via connectivity and interactivity

Supply chain management can also be used as a tool for enhanced environmental performance. Many companies in the forest industry have implemented environmental management systems such as ISO 14000. As the use of these systems matures, the integration with management tools such as SCM will allow companies to view the supply chain not only through the ideals of improved customer satisfaction and lower costs, but also through improved environmental performance. Climate change strategy is the area where companies are currently focusing with respect to environmental performance, including reverse logistics and ecorouteing.

Supply Chain Management in a Marketing Context

One way to see and use SCM is to equate it with logistics, in which case the objective is to economically optimize the physical product flows from producer to customer. The supply chain can be extended to cover the flow from raw material suppliers to the customer. Effective use of information is the main tool of economic optimization.

The broadest definitions of SCM cover the whole business. SCM is seen as a management tool for integrating and coordinating raw material procurement, manufacturing, and marketing. The goal is to achieve internal efficiency and customer satisfaction by being able to deliver a perfect order (i.e., giving to customers what they want, when they want it, in the right quantity, and at the right price).

We suggest that SCM should be seen in a strategic marketing context. It is a management tool to implement marketing strategies by seeking cost effective solutions and solving problems connected to material and information flows between supplier and customer. The final goal is value creation for the customer.

5.1.4 The Future of Marketing Management

As can be seen from the previous discussion, a range of factors is contributing to the changes in the way companies manage the marketing function. Technologies are opening up new possibilities for communication and business management. Globalization has forced companies to reconsider logistics as they source raw materials globally and market to global customers. Heightened competition is causing companies to reconsider the traditional adversarial approach to other channel members. Instead they are concentrating on becoming customer-focused. To do this, companies are working to eliminate functional boundaries, creating cross-functional teams, and seeking relationships and alliances with outside partners.[26] Each of these factors, in combination with the rate of change in the marketplace, is forcing companies to reconfigure their basic structure away from hierarchies towards the flexibility of networks.

Firms are beginning to view networks as a competitive necessity, since competition is increasingly based on a network-to-network paradigm, rather than firm-to-firm.[27] E-commerce and advanced IT capabilities are helping evolve the supply chain into what can readily be seen as a network. Figure 5-5 shows the evolution to an e-commerce-facilitated network. The idea is that e-commerce allows not only the connecting of firms, but the coordinating of firms and their inter-firm processes. This creates a coordinated – rather than a merely connected – environment.

- Connected environment – a company creates a forecast and passes the information to its downstream partners. Information can become easily distorted because of multiple hand-offs down the chain.

- Coordinated environment – all members of the channel collaborate together to create a forecast. Each participant has good visibility into the same information base.[28]

A network structure is inherently more flexible and more efficient in moving information, allowing the firm to continuously adapt to change and become superior in learning. In a network organization, there are task- or skill-specialized units that operate as an interdependent coalition without hierarchical control. The units (often cross-functional teams) are closely linked with other units in the company and share a value system that defines roles and responsibilities.[29] Just as marketing has generally evolved toward closer relationships, the units or departments in a company are moving toward closer interaction and cooperation. Key account management is a good illustration of this idea, where cross-functional teams manage important customer accounts. This is only possible through close cooperation among the various units of the firm.

As a result of these many changes, the significant role of marketing in the organization will continue to evolve. Marketing will be an expert on the customer and will keep the network organization informed about the customer. The marketing department will create knowledge from information. For example, marketing might create expert systems and decision models that can be used on an interactive basis by field personnel. Marketing has the potential to be the strategic core of the company by acting as the network integrator helping shape the company’s external network of partners. Marketing will also have the responsibility for managing team-based processes.[30],[31],[32],[33]

Even though marketing as a function will remain important, it will increasingly be seen as a philosophy or orientation that is present throughout the company. Marketing will not be the sole responsibility of specialists, but everyone in the firm will have the responsibility to understand customers and contribute to the delivery of value. Accordingly, a major role of the marketing specialists will be training and educating other members of the organization about marketing and the customer.[34],[35],[36],[37]

Marketing strategies and the management of structures and functions must change to meet an evolving business environment. Technology development will continue to provide potential enhancements to marketing in the forest industry. Business management structures in the industry will continue to change in order to take better advantage of technology and business management innovations.

5.1.5 Choice of the Management System

In previous sections we analyzed relationship marketing, supply chain management and the role of IT in connection with marketing management. In customer-oriented companies, marketing aspects are central to general management approaches. When choosing a marketing management system, we can consider a variety of approaches or combinations of approaches.

When new management systems or approaches (fads) are continually introduced to the business world, there is a danger that the basic principles and structures of marketing are forgotten. When adopting new, popular ideas, their connection to strategic marketing contexts must always be considered. Enthusiastic authors believing in their own ideas may indicate that a new system solves all marketing problems. They may even indicate that the new system can replace the principles of general marketing thinking. However, it is improbable that the whole marketing paradigm can be replaced. Recent popular management approaches have many valuable characteristics, but before considering implementation, they must be carefully evaluated in the context of the company’s strategic marketing plan.

Modern marketing management approaches generally follow the principles of customer-oriented marketing – they fit special or custom-made product strategies and selective customer strategies. Our view is that in most cases, a company does not choose a management system per se, but combines those aspects of various systems which best implement the chosen strategies.

Relationship Marketing & Customer Relationship Management (CRM) – CRM is a general management approach following the philosophy of customer orientation. In a strategic marketing context, CRM is a natural choice when customers are known and products are custom-made. The company wants to emphasize long-standing customer relationships, with mutual commitment and trust.

Strategic or Key Account Management (SAM) – A company following selective marketing strategies (known end-users) may realize that some customers are clearly more important or profitable than others and should be prioritized in marketing. Appropriate ideas for managing these customers may be found in the principles of SAM. SAM gives guidelines for choosing strategic accounts, how to keep them, and how to increase the profitability of these customers to the company.

Supply Chain Management (SCM) – SCM emphasizes streamlining the chain between supplier and customer. Streamlining the supply chain means cost savings to all of the participants of the distribution structure. This should motivate participants in the chain towards closer cooperation and integration. Transparency and effective use of information are the most powerful tools of SCM.

As a method for improving logistics, SCM could be connected to both selective and unselective marketing strategies. Theorists developing SCM argue that the final aim of SCM is increasing the value to the customer, and that this implies a customer-orientation. Streamlining the supply chain also means close cooperation and system integration between the supplier and customer, which is only possible between companies that have deeply internalized the idea of partnership. This also implies that SCM is connected to a customer-orientation and selective marketing strategies (known end-users).

Environmental Management & Environmental Management Systems (EMS) – If a company is responding to environmental issues in its marketing, this can be supported by environmental management and environmental management systems. The holistic view of environmental marketing demands that ecological issues must be integrated on each level of marketing decision-making, strategies, structures, and functions. Environmental management systems support environmental marketing by guaranteeing that environmental issues are taken into account at every stage of production. An EMS can be broadened to cover raw material procurement and product distribution. The main ingredients of an EMS are company environmental policy, mapping the environmental impacts, and a plan to reduce the harmful environmental effects of the company. Climate change strategies and carbon footprint reduction are areas of high focus among forest industry companies today.

A company can certify its EMS and use the certificate as a marketing tool to indicate that environmental issues are taken seriously by the company. All partners in the supply chain or network may need a certified EMS to prove environmental friendliness of the entire supply chain to the final customer.

IT in Marketing Management – IT applications are a part of all the above-mentioned management approaches. IT has had, and will continue to have, a profound effect on business. Because of its systematic nature, IT will deepen partnerships by forcing suppliers and customers to integrate their systems. All transactions that can be automated will be in electronic information networks in the future.

However, while IT can make business relationships closer, it can also make them more distant. Information sharing and integrated information systems are examples of closer relationships. Trading through e-marketplaces is an example of more distant business connections. The challenge for management is to choose the future direction of IT-supported business.The failure of most forest industry e-marketplaces in the early 2000s illustrates that closer, not more distant, relationships are necessary for business-to-business marketing (Example 5-3).

Example 5-3: The Development and Demise of Electronic Marketplaces

At the turn of the century there were major developments in electronic marketplaces in the forest sector. An electronic marketplace is a Web service provided by a third party and is basically a vertical portal including several suppliers. Typically the marketplaces were separate for chemical and mechanical forest industry products.

A marketplace allows customers to search available items from stock notes provided by sellers. It also allows customers to make enquiries to all or some of the sellers in the marketplace. It allows the customer to search the availabilities and receive quotations from a large number of suppliers in a convenient manner, on a single Website. On the other hand, relying on a random supplier making the cheapest offer can also cause problems in reliability and product and service quality.

It is difficult to describe the characteristics of a product or a producer in detail on a third-party Website. This means that the competitive situation is intense, and buying decisions are essentially dependent on availability and price. Obviously this is not a desirable situation for companies trying to establish competitive advantages beyond price leadership. Generally, third-party marketplaces counter the idea of special and custom-made products, which may explain why most of the marketplaces failed.

A marketplace that has survived since the early days of electronic marketplaces is FORDAQ, The Timber Network. The company describes itself as a communication and information network tailored to the needs of the timber professional. With over 200,000 members in 186 countries, the company provides a mechanism for buyers and sellers to connect. Beyond the marketplace, the company offers a directory of members, daily industry news, and other services.

5.2 Organization

Companies, associations, and most organizations are based on the idea of combining human resources. People are specialized to conduct various tasks, and the combined result is bigger or better than that which could be achieved through individual efforts. The goal behind the division of labor is to use human resources as effectively as possible and this is matter of organizing.

5.2.1 Basic Idea of Organizing and Organization

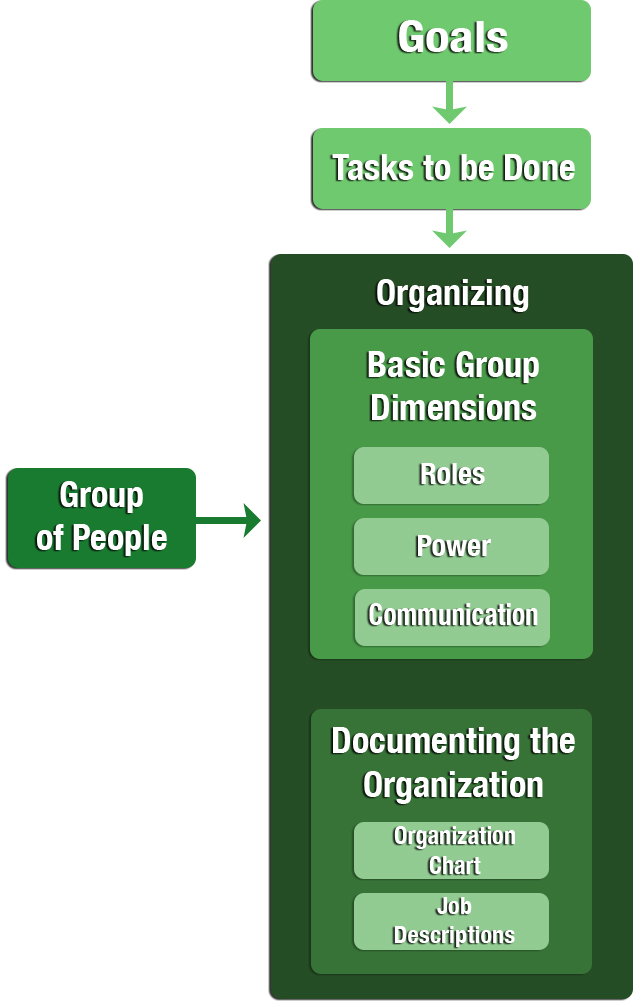

The term “organization” is often used to describe a whole company; however, in this case organization refers to the way tasks in a company are divided among people or groups of people. In an organization there is a stable division of roles that dictate who does what, who is responsible for what, and who controls what people. In other words, in a company the organization defines the internal division of power, responsibility, and communication. A simple idea of organizing can be seen in Figure 5-6.

Goals – On a very general level the mission defines the goals of a company. According to the basic idea of strategic marketing, marketing strategies contain the goals of a company. The structural requirements of an organization are derived from the strategies. The organization must be planned so products are marketed as effectively as possible to defined customers in defined market areas, using the company’s core competencies.

Tasks to be done – Marketing science and practice have created descriptions of the tasks included in marketing. The IMMP and its operationalization is one example of a systematic way to describe marketing tasks. Marketing philosophies and various marketing management approaches emphasize different tasks in marketing. For example, SCM emphasizes logistics, while CRM and SAM emphasize customer relations and customer support.

Group of people – Marketing tasks are conducted by a group of people. The challenge for the organizer is to structure the tasks in an appropriate way and to assign the best possible person to each job. An educated, motivated, and skilled team is the best possible starting point for marketing success. A critical task for the manager is to collect a good team, keep it motivated, and continually improve its performance.

Organizing – A group of people and a list of tasks to be done is the starting point for organizing. Organizing requires understanding the basic dimensions of human organizations (groups) and knowledge of formal structures of organizations.

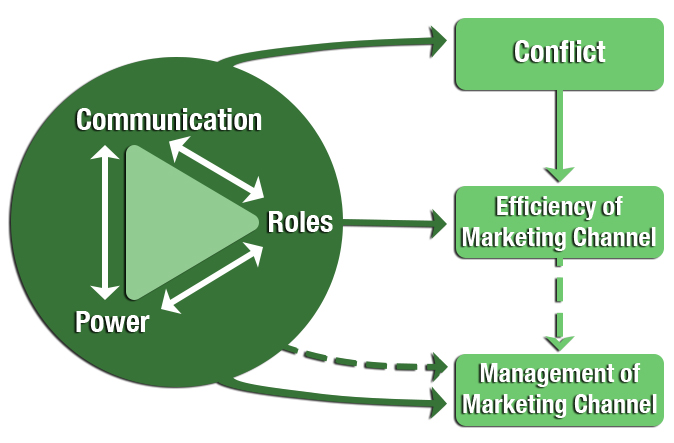

Basic group dimensions – Social psychology is a behavioral science that contributes to an understanding of organizations, because it studies how groups, such as companies, function. As to the performance of a group, the most important internal dimensions are: roles, power, and communication. The better the roles are defined, the power is balanced, and communication is arranged, the better the group performs.

Roles are positions in a group identified by certain tasks associated with positions. Group performance requires power relations between role positions. Responsibilities must be clearly defined. This leads to hierarchical, supervision-reporting relations. Communication is a tool that allows the group (organization) to function. Without proper communication, there is no group performance. The manager must regulate and balance the social processes in an organization.

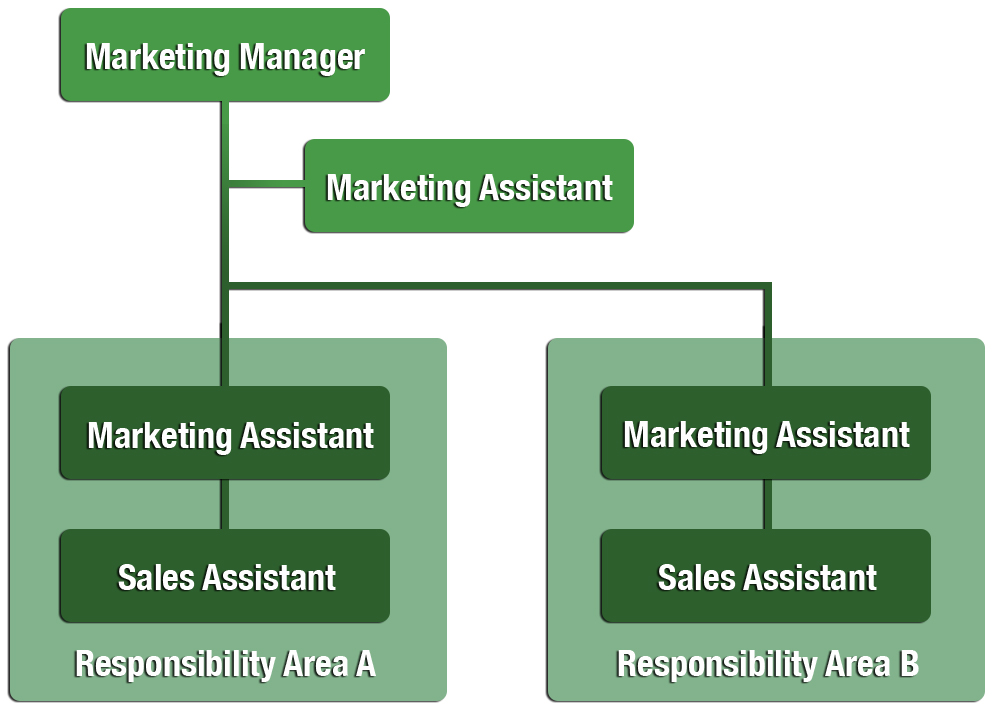

Documenting the organization – Although it is often difficult to describe the roles, power, and communication in complicated relationships, organizational structures must be documented for various purposes. Often, if not always, detailed job descriptions are also documented. A simplified organizational chart is presented in Figure 5-7. Corresponding job descriptions are described below.

The marketing manager is the head of the marketing department. He or she may have a marketing assistant. The division of responsibility between the two salespersons could be based on products/product lines, markets or customers/end-use sectors. Each salesperson has a sales assistant.

Examples of tasks and responsibilities in a marketing organization:

Responsibilities of the marketing manager

- Planning business strategies (together with the managing director of the company)

- Strategic marketing planning

- Planning marketing structures and functions

- Planning and implementing the annual budget and marketing operations

- Supervising sales managers

- Contacting important customers

- Gathering, synthesizing, and maintaining market intelligence

- Follow up and control of marketing operations

- Reporting to the managing director of the company

Responsibilities of the marketing manager’s assistant

- Developing and updating marketing database

- Assisting marketing manager

Responsibilities of the salesperson

- Implementing marketing strategies by personal selling

- Planning of sales budget for area of responsibility (product, market, or customer segment)

- Search for new customers

- Contacts with customers

- After-sales customer support

- Handling claims

- Developing and updating customer database

- Reporting to marketing manager

Responsibilities of the sales assistants

- Handling sales documents

- Developing and updating end-user database

- Assisting salesperson

From these job descriptions, it is clear that the marketing manager is responsible for marketing planning, supervision, and control. His or her subordinates are responsible for individual marketing functions (personal selling in this case). The marketing manager is responsible for planning and the salespersons for executing the plans. The higher the organizational position, the more important it is to have total view of marketing and to be able to work with abstractions.

5.2.2 Basic Forms of Organizational Structures

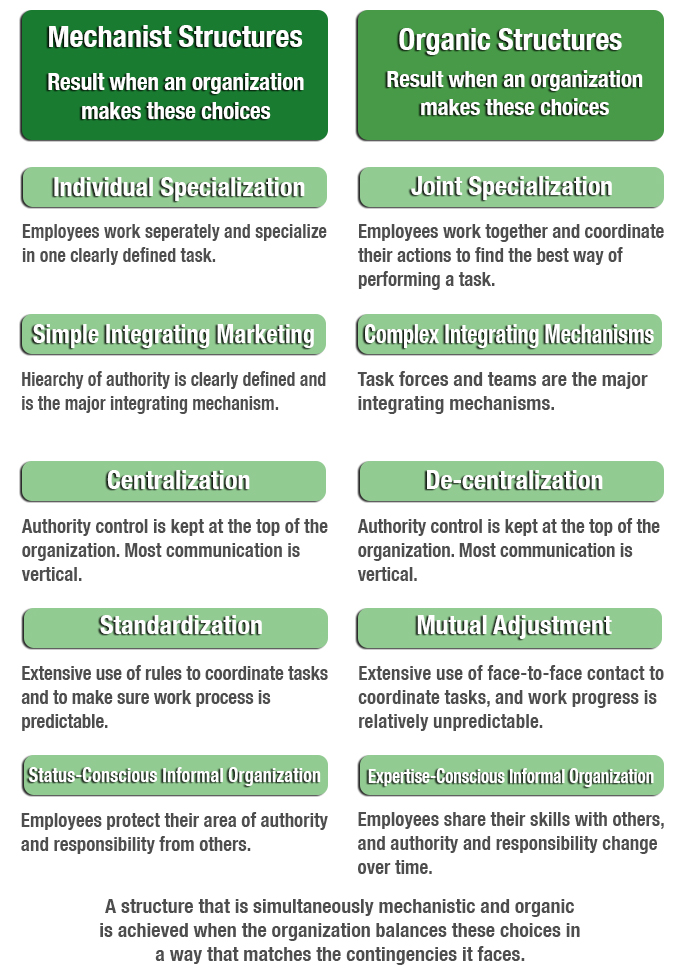

When considering organizational structure, it is important to think of both its vertical and horizontal aspects. Vertical design refers to the hierarchy within an organization; a company might have six layers of managers, starting at the CEO then stepping to the Executive Vice Presidents, Vice Presidents, General Managers, Sales Managers and equivalents, and line employees. Horizontal refers to the way the organization chooses to group its functions and/or divisions.[38]

Organizational behavior specialists speak of a continuum with mechanistic structures residing at one end and organic structures residing at the other (Figure 5-8).[39] In a sense, the mechanistic structure can also be labeled “traditional” and organic can be labeled “modern.” The mechanistic approach is hierarchical and bureaucratic; employees tend to specialize in their own thing and defend their turf from others. On the other hand, in an organic structure, there is a much stronger tendency to collaborate through teams based on shared authority.

The roles that marketing personnel play can vary greatly depending on the approach of the organization. A marketer working within a mechanistic structure might find him or herself in a corporate or division office with very little personal contact with production or sales. That individual would answer to one boss who would likely in turn report to the Vice President of Marketing. A marketer in an organic structure, however, would likely be in the field working with specialists from other areas of the company on specific projects. This individual might have two or more bosses depending on the number of projects.

Basic organizational structures are described below. It is important to remember that in real-world structures, there are often combinations of these theoretical types.

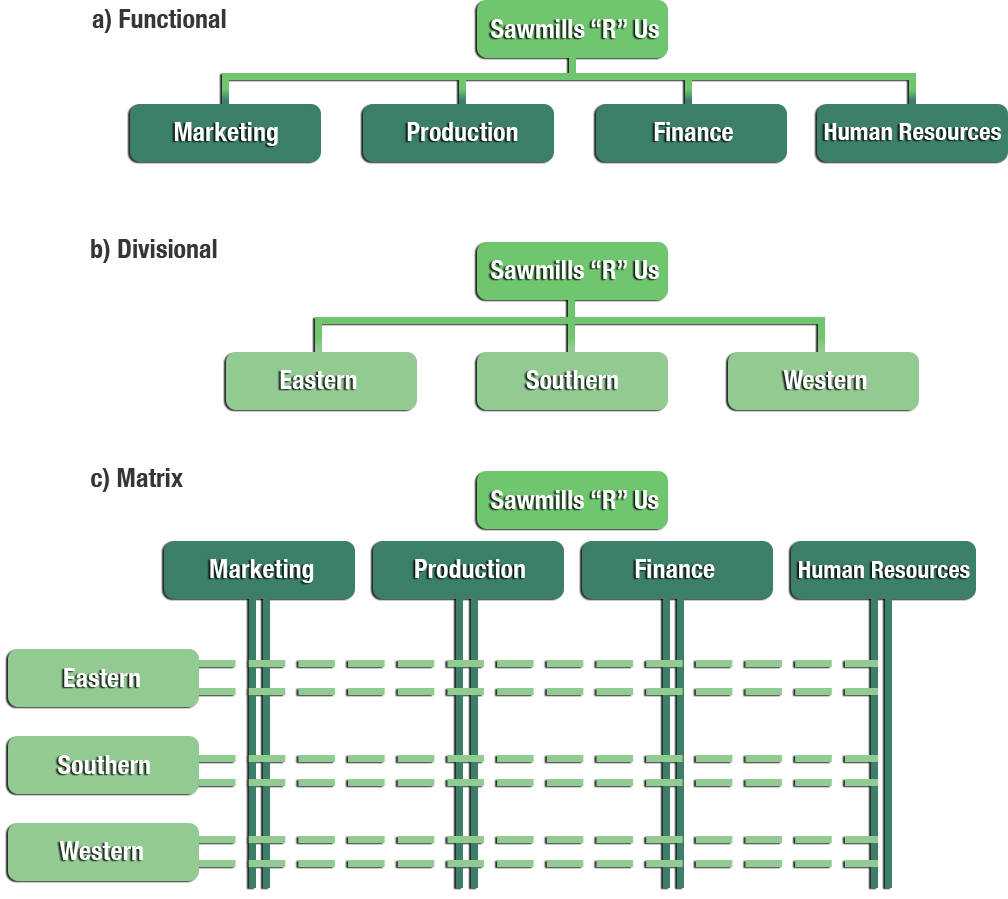

Functional Organizational Structure

A person in the marketing or engineering department is working within a functional area of a company. Companies can be structured around basic functions such as those shown in Figure 5-9, often referred to as silos, a reference to the vertical space they occupy in the organizational hierarchy.

Divisional Organizational Structure

A divisional structure is usually based on geography, products, or markets. A company in Brazil might have North American, Latin American, European, and Asian divisions. When based on products, the structure might include divisions associated with fine papers, packaging papers, and timber products. If a company is structured according to its markets or customers it might have publishing, packaging, and specialty paper divisions.

Matrix Organizational Structure

A matrix organization combines the concepts of functional and divisional structures. As shown in Figure 5-9, there is a vertical flow of functional responsibility and a horizontal flow of geographical areas. In practice each individual in the organization has two different bosses, one from the functional area and one from the product area.[40]

5.2.3 Choice of Organizational Model

Recent research has shown that there has been a general shift by firms toward customer-focused organizational structures. This means that there is increased emphasis on key account managers and cross-functional teams led by customer segment managers. This doesn’t necessarily mean that companies are always proactively working in this direction; rather, they are often pushed by customers who are becoming larger and more centralized in their purchasing decisions. This sort of evolution results in a more complex organizational structure. For example, individuals will report to more than one boss, as in a matrix structure.[41]

Large forest industry companies typically have divisional structures. The structure of the organization has a significant impact on marketing. We expect that companies in the forest industry will continue to evolve toward network structures and away from traditional structures.

Choice of the organizational model or structure is a corporate level decision, and marketers are likely to have little influence over the choice. Marketing personnel can actively minimize the drawbacks of any structure by working to fully understand those drawbacks and learning the best possible way to function within its confines. Marketers can work to negate some of the drawbacks of mechanistic structures by actively forming and working in cross-functional teams. However when companies increase their customer orientation, the organizational structures will also become more market-oriented. This means that the organizational structures are planned to serve customers in the best possible way.

5.3 Planning and Information Systems of Marketing

Management accounting and marketing research have traditionally been the main sources of internal and external information used in business and marketing planning. Although they have been computerized for decades, expanded and diversified computer applications that exist today lead us to speak of e-commerce. New systems make it possible to analyze and manage business processes more effectively than before. This means moving from data processing to knowledge management and problem solving systems.

The same systems carry information between business actors, register and analyze it, and may automatically create reports to be used in business planning. When electronic information systems support customer relationships, customer services, and channel intermediary relationships, they simultaneously register and analyze the behavior of all the actors. This information can then be used in marketing planning and customer relationship management.

The explosive growth in the information environment has created huge challenges for information systems. The danger of this technology is information overload – although information is abundant, it is often difficult to find useful and relevant information when needed. It is important that designers and users of marketing planning and information systems know and understand both the basic nature of marketing planning and the structure and content of the information environment. That is why we emphasize a scientific and planning approach to marketing planning.

IT has made it possible to develop a wide variety of management support systems for managers to cope in a complicated and demanding information environment.

Computer-based planning and information systems are built by IT-experts, but a marketing person must be able to cope in the IT-environment and use all possible systems and tools. IT will play a significant role in the future of marketing practice and will be both a challenge and an opportunity. Advanced tools are worthless if the user has not internalized the basic idea of marketing planning and the information needed. The next three sections aim to illustrate the context or framework where marketing plans are made and information is used.

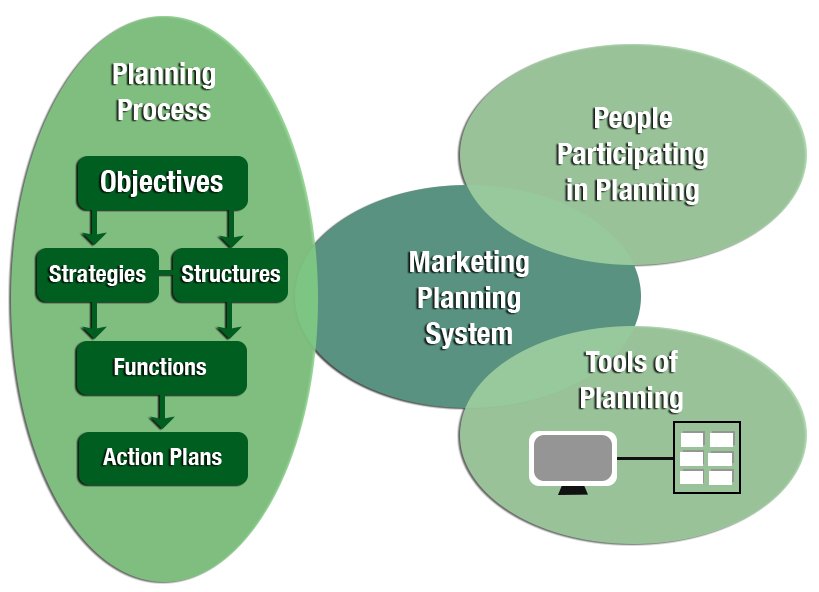

5.3.1 Marketing Planning Systems

Based on the IMMP we know what must be done when planning marketing. The marketing planning system explains the context of marketing planning and how it is executed. Marketing planning and planning systems are different from one company to the next, but it is possible to list the main components of the systems. According to Figure 5-10, a marketing planning system is composed of a planning process, the people participating in planning, and the tools used in planning.

Planning Process

If planning follows the principles of the IMMP, the stages of planning might be as follows (terms may vary).

Strategic Marketing Plan

- Marketing strategies

- Marketing structures

- Marketing functions

The strategic marketing plan builds a basis for marketing across the company. Strategies are developed or changed as needed, and structures and functions are developed or changed accordingly. Chapter 7 offers a real-world example of strategic marketing planning.

Marketing Action Plans

Marketing action plans are often called annual plans, operational plans, or simply budgets. What is important to remember is that action plans implement the strategic marketing plan on an annual basis. Production is allocated to customers and markets defined in the strategies. This allocation produces quantitative market and customer targets for the planning period. Financial targets can be created by adding price estimates to the plans.

It is presumed that on an annual basis, marketing structures are constant and follow the strategic plan. Marketing functions also follow the principles of the strategic plan, but specific annual plans are necessary in order to define how and when various marketing measures are used during the planning period, how much money is budgeted to marketing functions, and so forth.

Often, annual planning begins by updating strategies. If changes are needed, they are made, and structures and functions are then changed accordingly. Updating strategies is followed by other stages of marketing action plans. Chapter 7 offers an example of actual annual marketing planning.

Plans for Shorter Planning Periods and Follow-up

Shorter planning periods may mean quarterly, monthly, weekly, and daily planning. The market situation is dynamic – customers sometimes do not behave as expected, prices often fluctuate, and so forth. Reallocation of market and customer targets might be necessary. The better marketing can cope with its plans, the better possibilities there are for reasonable production plans. Regular follow-up is needed to determine how well plans have been carried out and if corrections are needed.

People Participating in Planning

Marketing planning is done in a team setting. All the people involved in executing the plans should be included in the planning processes, and several different teams may be needed. When strategies of an SBU are defined, they must be in accordance with divisional strategies. Division managers, SBU level managers, production managers, marketing managers, and sales managers must participate in the planning or updating of SBU-level strategies.

While it may not be necessary for division managers to participate in creating action plans on the SBU level, it is important that the SBU level manager, marketing manager, production manager, and sales manager all participate. Representatives of support functions may also be included. When quarterly, monthly, weekly, and daily planning is in question, people from lower organizational levels, especially from production facilities, are needed.

Tools of Planning

As mentioned above, planning and information systems have become increasingly integrated due to developments in IT. Planning systems cannot be described without information systems, and vice versa. As illustrated in Figure 5-10, tools of planning include information files, models, and methods to process information. Both external and internal information is used. In chapter 3 we broadly analyzed external information in marketing planning.

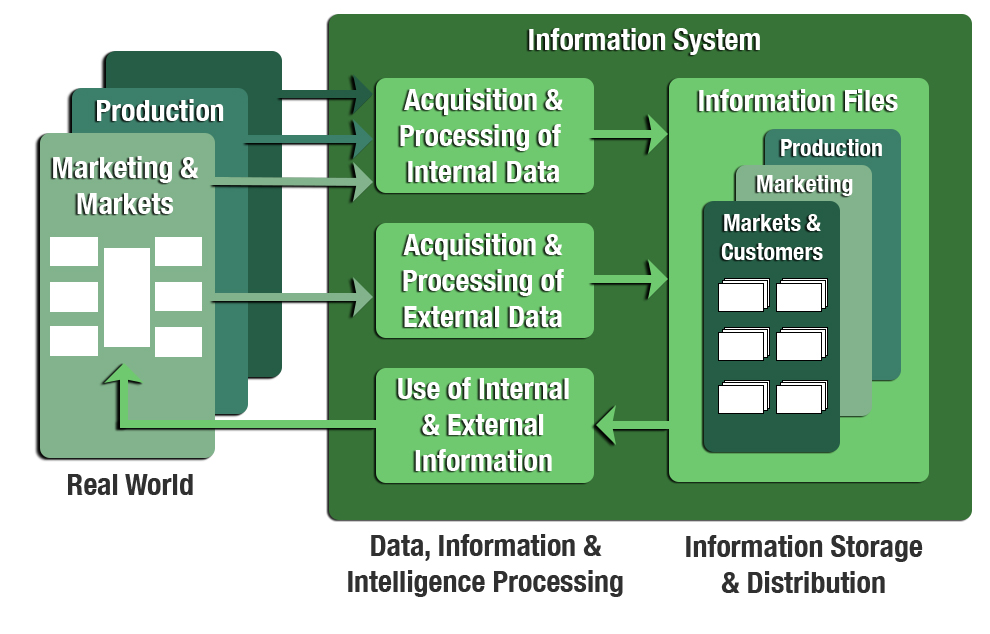

5.3.2 Information Systems

The first step in planning and decision-making is effective use of information and information systems. There is always room for improvement in the use of information. It may be that the manager has insufficient information, there is information that he or she does not know how to use, or that decisions are based on intuition even though the right amount and type of information was available.

In principle, every organization has some kind of information system, be it informal or formal. Broadly speaking, information systems can cover all the systematic processes that create the knowledge needed in business planning or everyday decision-making. A narrow definition of information systems refers to electronic systems and processes for collecting, analyzing and filing information for decision making in the organization.

Figure 5-11 presents how an information system acquires, processes, and files both internal and external information. Based on this view we can briefly define a marketing information system as follows: A system that acquires, processes, and files both internal and external information to be used in marketing.

Acquisition and Processing of Internal Data

Traditionally, sales figures, manufacturing costs, operating costs, and inventories have been the key data incorporated in the information system. Today, in principle, all company processes can be continuously traced by electronic systems and described through key figures/metrics that can then be used to improve those processes.

Accounting systems also produce internal information to be used in marketing planning. Financial accounting gives an overview of the financial situation while management accounting is designed to help managers make decisions.

Profitability information should always be emphasized in information systems since it is central in all strategic decision-making. Information systems must be planned so that profitability of products, customers, and market areas can be followed, as well as the costs of marketing structures and functions (especially logistics).

Acquisition and Processing of External Data

Acquiring information in a company can be irregular or regular, unsystematic or systematic. Typically in smaller wood industry companies, information acquisition is irregular and unsystematic. As companies grow, their information functions clearly become more sophisticated. The intensity and type of external data acquisition may vary considerably.

- Information may be collected as a part-time job in conjunction with everyday operations. Sales people report their customer visits, marketing managers follow trade magazines, intermediaries send market reports, and marketing research projects are conducted periodically.

- There may be full time information officers, marketing researchers, or marketing intelligence services or departments.

- Information needs may be partly or totally outsourced. Information for everyday operations or marketing planning is purchased from information agencies or research and consulting firms

Information Files

Collecting, analyzing, and storing information demands very specific skills, knowledge, and systems. Outsourcing may seem a natural choice to acquire these necessities. However, information is a strategic resource that the company should control. For example, information can be a success factor and a source of competitive advantage only if the company learns effective information management.

In any case, information management has proved to be a problematic issue. If information acquisition is irregular and unsystematic, it may be that information files are totally lost. Market research reports may be unused and simply gathering dust on the shelf of a manager. If full-time information officers and/or separate departments are responsible for information files, it may happen that the information is not used by those for whom it is meant – marketing directors, managers, and salespeople.

The biggest challenge with information files is to assure that the structure, content, and user interface are appropriate and attractive. The information should be in a form to help with everyday decision making situations or planning processes. The technical possibilities to construct information files (databases) are nearly unlimited. The one responsible for information files must fully understand the idea of marketing, marketing planning, and information in order to construct appropriate and attractive systems.

Use of Internal and External Information

As mentioned earlier, information should be in an appropriate and attractive form to be used in everyday decision-making. This means that the information must be compiled into a form that is easy for managers to use, whether it comes through a decision support system, or even a simple research report. Earlier this sort of information was available only in the manager’s office either in paper form or directly from a desktop computer. Today, information can be remotely accessed to assist decision-making in the field. As Figure 5-11 shows, marketing plans are implemented and feedback information is returned to the company’s information system. In many cases a manager will have a “dashboard” on her computer that displays key metrics for her area of responsibility. The dashboard will be tailored to her specifications so that she has precisely the information she wants at her fingertips.

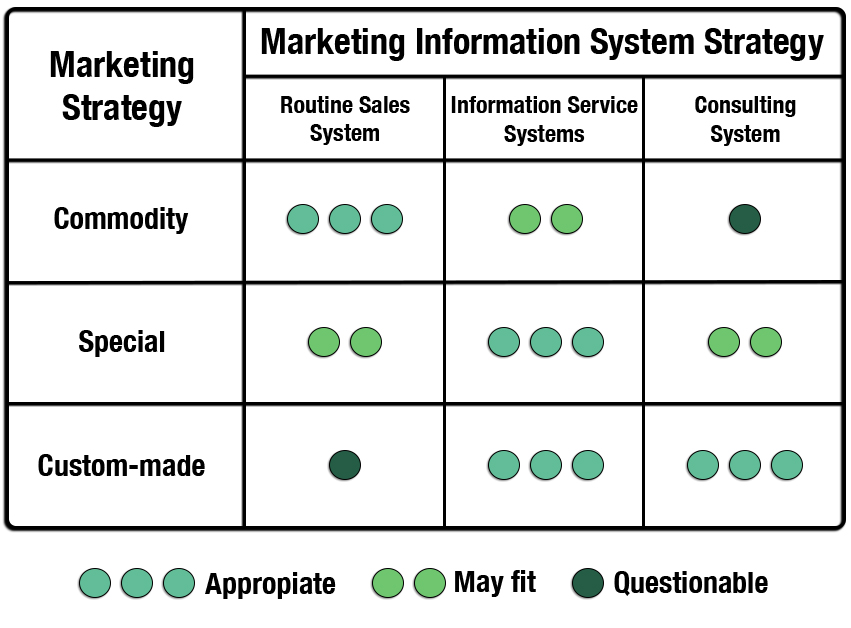

5.3.3 Relationship between Marketing Strategies and Planning and Information Systems

Advanced decision-making demands sophisticated information. Specifically, special and custom-made product strategies require more advanced planning and information systems than commodity product strategies. Toivonen analyzed this relationship empirically and based on a broad literature review drew the hypotheses seen in Figure 5-12.[42] Empirical data from the Finnish forest industry supports these hypotheses. The more selective the marketing strategy, the greater the emphasis on applications which support information services and consulting type of services in the marketing information system strategy.

5.4 Marketing Channels

5.4.1 Concept and Nature of Marketing Channel

In most cases a forest company does not sell its products directly to the consumer. Products are transferred as a result of the cooperation of various companies and organizations. The marketing channel can be viewed as a link between the producer and the consumer. We define marketing channel as all the organizations, functions and flows that are needed to get the product or service from producer to customer. Sometimes the term marketing channel is confused with the channel of physical distribution. According to our definition, physical distribution is a part of the marketing functions in a marketing channel, but there are also many other functions. A channel of physical distribution contains all those organizations and functions that facilitate the physical flow of products. A channel containing buying and selling organizations, or those organizations facilitating buying and selling, can be called a contact channel. Marketing communication and collecting market information are examples of marketing functions facilitating buying and selling. So a company’s advertising and market research agencies are part of its marketing channel.

From a production point of view, the marketing channel might be seen as a buffer between the production unit and the environment. It should cushion the shocks and discontinuities coming from the market. This is especially important in capital-intensive, process industries like the paper industry since there must be a continuous flow of raw materials to the production core of the company and continuous flow of products from the production core to the markets. It is the responsibility of marketing and the marketing channel to assure this continuous flow. In some cases the speculative behavior of the marketing channel intermediaries strengthen the fluctuation of demand. This happens most frequently with commodity products like sawn timber and pulp, where the marketing channel can work against its original purpose and principles.

Because connecting the producer and the customer can be seen from many different perspectives which emphasize different issues, it is worth reviewing the following definitions:

Marketing Channel – creates a relationship between the producer and customer. Included in that relationship are all the measures needed to move products and/or services from producer to customer. The relationship can be direct or through intermediaries (merchants, agents or facilitators). The marketing channel concept emphasizes managing the relationships between marketing channel members to execute the marketing measures to the full satisfaction of the customer.

Channel of Physical Distribution – enables the transportation of products from mill to customer. It contains the organizations which facilitate the physical movement of products. The basic components of physical distribution are order processing, inventory control, material handling, transportation, and warehousing. Physical distribution emphasizes satisfying customers with the right product in the right place at the right time at a minimal cost with the desired service level.

Supply Chain – The supply chain begins earlier than the marketing channel and includes raw material supply and manufacturing. Supply chain management (SCM) can be defined as management of upstream and downstream flows of products and information between raw material suppliers and customers to deliver superior customer value at less cost to the supply chain as a whole.[43] SCM emphasizes optimized product flows and abundant and transparent information flows.

Value Chain – A supply chain can be interpreted as a value chain creating value for the customer all the way from the source of the raw material to the final end-use of the product. To gain competitive advantage over its rivals, a firm must promote value to its customers through performing activities more effectively than its competitors or by performing activities in a unique way that creates superior buyer value.[44] The value chain emphasizes optimal or differentiated accumulation of customer value.

Distribution System – Each market has its own structure of marketing channel intermediaries. This structure provides possibilities and limitations to the marketer in arranging marketing and choosing marketing channels in that particular market. We call the structure the “distribution system of the market.”

Because a marketing channel is a group of independent organizations that work together to make a product or service available to a customer, it can be seen as a network creating value for the customer. There are three basic kinds of organizations within the channel. First are intermediaries that buy and sell a product (take title). These merchants can be organizations such as wholesalers, stocking distributors, and retailers. Agents do not take title of the product, but negotiate a deal between the buyer and the seller and often make transportation arrangements. A final set of organizations provides services that facilitate the activities of the marketing channel and are called facilitators.[45] Facilitators consist of companies involved in transportation, storage and warehousing, advertising, finance, insurance, and marketing research.[46]

5.4.2 Objectives and Functions of Marketing Channels

Objectives for a company’s marketing channel are dictated by product, customer, market area, and core competency strategies. For example, the marketing channel must move the product defined in the product strategy to the customers and markets defined in the customer and market area strategies and be supported by the company’s core competencies.

The objectives of marketing channels can also be defined more precisely – if, for example, customers emphasize reliability of delivery, the company should also emphasize this aspect in its objectives. If the company is emphasizing special or custom-made products, the marketing channel must be able to carry information and create closer contacts with customers.

A number of different flows occur in a properly functioning marketing channel:

Product flow – physical flow from producer to customer

Negotiation flow – deal making among members of the channel

Ownership flow – movement of product title among the channel members

Information flow – both up and down the chain

Promotion flow – advertising, etc. used to communicate with customers[47]

Merchants, agents, and facilitators perform a variety of functions to assist in delivering a product to the customer. A company can own or control major components of the marketing channel. Larger companies in the North American forest industry commonly developed their own distribution businesses in earlier times, but most have exited this business area. For example, Georgia Pacific was a major distributor of building products in the US, but chose to sell that business (now operates as BlueLinx). Global paper companies tend to operate their own marketing channels, at least for their largest customers. However, smaller companies are more reliant on other organizations to form the marketing channel. This is also true of larger companies, if they are serving a diverse set of small customers or final consumers. A final consumer usually wants to:

- Buy small quantities at a time

- Buy from a close-by location

- See the product before purchasing

- Buy other products at the same location

- Easily access service designed to his/her needs

Because consumer preferences are so specific, few companies have the resources necessary to provide all the functions of a full marketing channel. Even if a company has the resources to have its own captive marketing channel, it may not be in its best interest to do so. Instead, it may be more productive for the company to concentrate on its core operations.

Intermediaries in the marketing channel provide services that benefit both the producer and the customer. In essence, they shorten the distance between the producer and the consumer in terms of time, culture, etc., and they move information in both directions. Below is a summary of some of the key functions of intermediaries.

Relationship maintenance with final consumer – With a product that is consumed by many people, it is difficult to maintain so many relationships. As the customer base in some sectors moves increasingly towards end-users, the number of contacts increases rapidly. An intermediary can take care of this. On the other hand, if a company’s total customer base is few in number, it may make sense to have in-house sales and distribution.

Handling details of price and delivery with final consumer – Every time someone orders a product, a transaction cost is incurred. Once again, if there are many customers placing orders, it may be advantageous to let an intermediary handle much of the order taking. For sawn timber, the average importer may buy 1000-2000 m3 per shipment, whereas the average industrial end-user may need only 50-100 m3. Using an intermediary allows the company to process a few large orders from the intermediary rather than numerous small orders from final customers, effectively reducing total transaction costs.

Provide credit/collection – accounts payable can be a significant problem for the small business, as the delay in payment interrupts cash flow. Another significant problem is bad debt – those companies that buy a product but choose to never pay. Letting an intermediary handle credit and collection effectively lowers risks. In addition, changes in the global financial system as a result of the Great Recession has increased the difficulty for small companies to obtain debt financing or a line of credit.

Provide inventory/storage – Space constraints, inventory holding costs, demands for just-in-time delivery, and demand for large orders all may be good reasons to let an intermediary take care of inventory and storage. To the extent that the intermediary can provide these services more efficiently, the producing company’s costs may decline and total product utility may increase.

The functions of marketing channel intermediaries can be derived by analyzing the basic task of marketing and can be classified according to the functions mentioned in the Integrated Model of Marketing Planning:

Personal contacts

- Maintain personal contacts with industrial end-users

- Maintain personal contacts with other intermediaries

Marketing communication

- Direct advertising to the end-user

- Produce newspaper/magazine advertisements

- Produce brochures and similar material

- Conduct product demonstrations or participate in trade shows

- Carry out public relations work

Market information

- Collect and transfer market information

- Carry out marketing research for marketing planning

Functional communication and service (routines of marketing/selling)

- Deal with all sales contacts

- Deal with contracts and agreements

- Transfer title

- Service the product and provide other services (e.g., maintaining displays)

- Provide customer service

Product planning

- Provide market and customer information for product planning (product development)

- Contribute/participate in new product development teams

Pricing

- Provide market and customer information for pricing

Physical distribution

- Arrange transportation

- Warehousing

- Provide bulk breaking service

5.4.3 Structure of Marketing Channels

Structural Alternatives

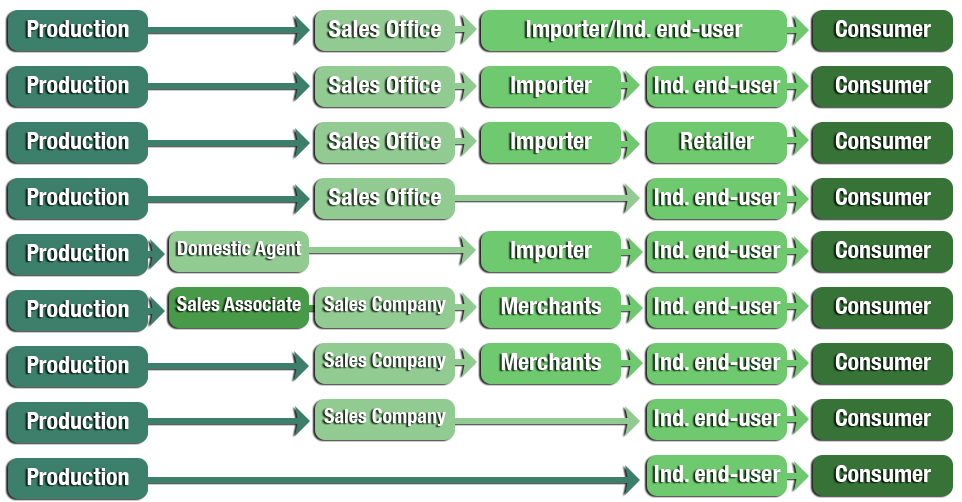

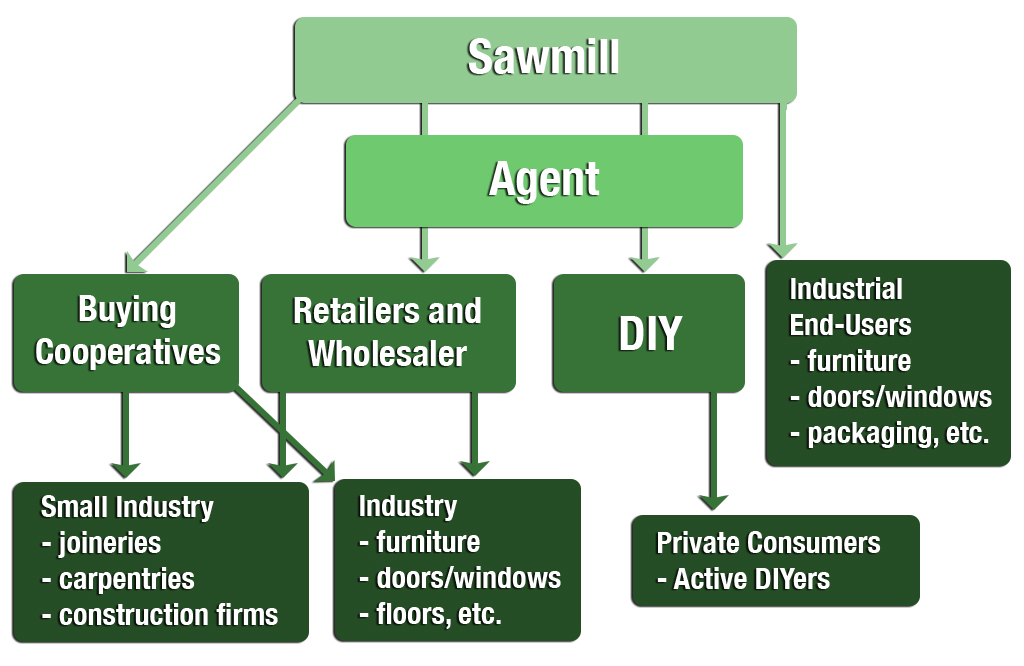

The concept of the marketing channel structure refers to different intermediary chains functioning in the marketing channel. In theory, almost any combination of intermediaries is possible; however, for any one industry sector, there will be only a few combinations that account for the majority of product flow. For example, the producer might use an in-country (domestic) agent in order to export products to another country. That agent might arrange for the product to be sold to an importer in the other country that in turn sells the product to an industrial end-user and, finally, the product arrives at the final consumer. Figure 5-13 provides examples of marketing channel structure alternatives.

A significant change over time in marketing channels has been disintermediation. In other words, intermediaries are being eliminated from the channels, in favor of more direct distribution. In the 70s, small sawmills might have utilized a channel that included export and import agents, an importer, and a distributor. However, by the 90s this had changed significantly, with larger companies using a more vertical structure with more steps under their immediate control (Figure 5-14).

Intermediaries in the Marketing Channels

The role of intermediaries can vary depending on market areas and the historical developments of trade and marketing channels in a country or region. In some countries big importers are dominating the majority of retail trade. In other countries, agents have an important position in the marketing channel. The same company can perform the jobs of several traditional intermediaries. Generally it can be said that there are fewer intermediaries today than in the past. This is partially a result of larger customer or producer companies and the power they bring to the marketplace. However, equally important is a new preference by customers, especially industrial end-users, to deal directly with the producer rather than an intermediary. Often they want to deal with the person in the mill that can actually make decisions rather than filter the communication through different levels of intermediaries.

It is important to note that names for intermediaries differ from one country to another – and even sometimes within countries – even when they provide much the same service. For example, the US Census Bureau divides wholesalers into three different categories:[48]

Those that sell goods on their own account – wholesale merchants, distributors, jobbers, drop shippers, import/export merchants.

Those that sell goods manufactured by the parent company – manufacturers sales branches and offices.

Those that arrange sales and purchases for others for a commission or fee – agents, brokers, commission merchants, import/export agents and brokers, auction companies, and manufacturers’ agents.

While this categorization is useful, it does not fully describe the situation in the wood products industry. For example, in the first category above, the Census Bureau states that goods are generally sold without transformation. This is not always the case in the wood products industry, as is shown in the discussion of wholesalers below. In fact, one major category of wholesalers in the wood industry is those that re-manufacture and resell the product. In the following sections we give an overview of the major intermediaries in the forest industry marketing channels. Example 5-4 provides examples of each of the types of intermediaries outlined below.

Example 5-4: Examples of Intermediaries in the Value Chain

Agent – Gratenau & Hesselbacher GmbH

G&H is an international trading group located in Hamburg, Germany. The company was founded in 1874 and is involved with trading pulp, paper, and packaging products.

Sales Office – Stora Enso (France)

Stora Enso maintains a sales office in Lormont, France for its wood operations.

Importer – Vanport International, Inc.

Vanport International does both imports and exports via its head office in Boring, Oregon as well as through its representatives in Japan, Europe, South America, and throughout Asia.

Wholesaler – Forest City Trading Group, LLC

Forest City Trading Group, LLC was established in 1964 in Portland, Oregon. With 12 operating divisions and 305 traders, the company offers a wide range of lumber and panel products as well as other building materials.

Reload Center – Westran Services Limited

The Westran group of companies specializes in transloading services. Its roots are from 1985 when it was formed to provide British Columbian mills access to the Burlinton Northern Railroad (now BNSF).

Industrial End-User – 9 Wood

9Wood, Inc. is a manufacturer of suspended wood ceilings. Formed in 2004, the company is located in Springfield, Oregon. Their products utilize a variety of species and typically are used in high-end commercial applications.

Retail Store – Kingfisher

Kingfisher is a retail group that includes multiple store brands and employs nearly 80,000 people across 1,300 stores. One Kingfisher brand, B&Q, is a DIY retail chain similar to The Home Depot in the US. B&Q is the largest DIY chain in the UK with nearly 300 stores.

Agent

An agent is a general term for intermediaries that do not take title to a product but rather negotiate sales between buyer and seller. The two most common agents in North America are brokers and manufacturer’s representatives. Brokers are common players in situations where large quantities of bulk goods are being handled. Manufacturer’s representatives are like salespeople for hire; they substitute for a company’s sales force. Manufacturer’s representatives are still important in some parts of the building products marketplace in the Americas.

In countries that are more import- and export-oriented, export and import agents are common, ranging in size from very large organizations to one-person companies. The position of these agents has generally weakened in many market areas. For example the use of both export and import agents by Finnish companies has decreased because the number of small sawmills has decreased and the bigger companies have created their own sales offices in the main countries in middle Europe. In addition, even those companies without sales offices have developed the expertise to handle the services typically offered by an agent. Smaller agents who specialize in specific geographic areas and clearly identified end-use markets have more recently been formed. Today, large companies typically use agents for smaller market areas and in countries that are not an important component of total sales.

Small companies still see agents as a cost-effective alternative when attempting to cover a wider market area.