Chapter 1 : The Context of the Forest Industry and its Markets

After reading Chapter 1 you should understand the following:

- Where global forests are located.

- Where production of major product categories takes place.

- Why societal concern about the environment is important for forest products marketers.

- How major societal trends are impacting the forest sector and forest products marketing.

- How the forest industry is changing to deal with major societal trends.

This chapter sets the stage and provides the context for the marketing of forest products. The forest industry is increasingly global and every marketer of forest products should have a global perspective. As a natural resource-based industry, the forest industry has an especially high profile role in environmental protection and is increasingly involved in climate change mitigation and management. Global forests are not only important because they provide a source of industrial raw material, but also because of the various other human needs they satisfy. A forest products marketer should have a basic understanding of the role that global forests play in society. Major societal trends are impacting the external environment within which the forest industry operates. We provide an overview of global forests and a brief description of the markets for the main categories of the forest industry. Following this we outline several important societal trends as well as how the industry is evolving over time and conclude with a brief description of what this means for business and marketing in the forest industry.

The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations follows the development of global forests and regularly provides information about forests and how they are changing. The world regions as used by FAO are generally: North and Central America, Europe, Asia, South America, Africa, and Oceania (Figure 1). Some documents by FAO may have slightly different regional groupings.

1.1 Global forests

In 2015 the world’s forest cover was 3.99 billion hectares. Europe has the largest forest area (25%) as it includes the Russian Federation, which alone comprises 20% of the world’s forest area, at nearly 900 million hectares. Because of its size, the Russian Federation dominates any analysis of forest resources. Brazil has the second largest forest area globally with over 494 million hectares. Africa contributes significantly to the world’s forest resource with 624 million hectares of forest. The 18.8% of world forest cover found in North and Central America primarily lies in Canada and the U.S. The world’s total growing stock is estimated to be 531 billion m3 [1]

Although in the context of this book forests are important for the wood they provide, it is important to recognize the myriad products and services that forests provide beyond wood. Much of the world’s biodiversity is associated with forests, especially tropical forests. Many people around the world rely on forests for a wide range of non-wood forest products such as foods and medicines. Energy from wood is critical for about 2.4 billion people around the world and forests provide 40% of global renewable energy. [2]

Ownership of forests varies considerably among countries and regions. Public or state-owned forests are the only ownership type in the countries of the Commonwealth of Independent States (Russia, etc.). Canada is similar with over 90% of forestland owned by the government. On the other hand, in the US and much of Western Europe, private ownership is the norm. Family or individual ownership is often over 50% of the total forestland in countries such as Finland, Sweden and the US. Community ownership is important in many countries. For example, in Mexico community ownership represents 80% of total forestland.[3]

1.1.1 Plantations

In recent decades, establishment of plantations has taken place on a grand scale. Up-to-date statistics are hard to find, but as of 2000, about 80% of the area in plantations (111 million hectares) was dedicated to production of wood and paper products. The other 20% was largely established for protection functions.[4] Asia contains the largest area with nearly half of the global total. Countries best known for production of industrial roundwood from plantations include Brazil, Chile, Uruguay, New Zealand, and South Africa.

Globally, plantations provide for approximately 33% of industrial roundwood. Another 54% come from natural forests and 12% from semi-natural planted forests. South America boasts the largest global production of industrial roundwood from plantations at 193 million m3 (88% of production) followed by Asia with 151 million m3 (43% of production) and North and Central America with 104 million m3 (22% of production). Oceania is relatively low in total production (47 million m3), but 81% of its industrial roundwood comes from plantations.[5]

1.2 Global markets

Below we describe the basic characteristics of global markets for several general categories of wood-based products. There are a large number of wood-based products that are not addressed here, but the categories below account for the main volumes of wood-based products. Traditionally, the US was the largest producer and consumer of most categories of wood products. Wood products markets are changing quickly and other countries, especially China, are playing a bigger role both in terms of production and consumption.

According to FAO[6] there are five major drivers of change impacting the long-term demand for wood products:

- Growth of world population

- Growth of global GDP

- A significant shift in GDP share to developing countries

- Exclusion of more forests from production due to environmental policies and regulations

- Energy policies that encourage the use of biomass

According to FAO statistics, global production of roundwood in 2016 totaled 3.74 billion m3. Of this total, nearly 50% was used as wood fuel with the other half being industrial roundwood. The way wood is used is highly dependent upon the level of development in a country. A split can be seen between the predominant use of fuel wood by developing countries and industrial roundwood by developed nations.

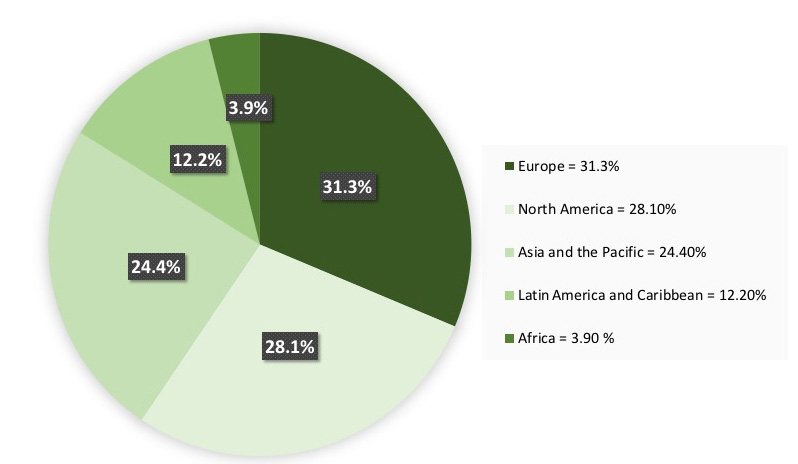

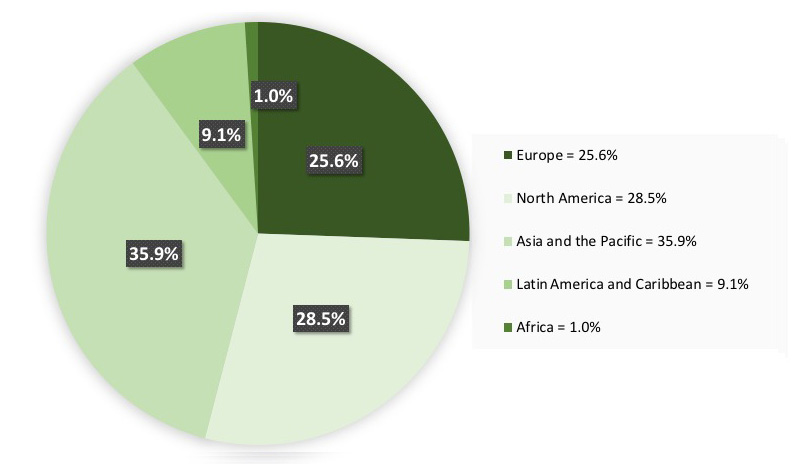

The remaining information from this section comes from the 2015 Global Forest Products Facts and Figures from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.[7] Global production of industrial roundwood in 2015 totaled 1.85 billion m3 with Europe representing the largest proportion (because Russia is included in Europe) (Figure 1-2). Approximately seven percent of this volume entered international trade. Regionally Asia and the Pacific is a net importer, with all other regions being net exporters.

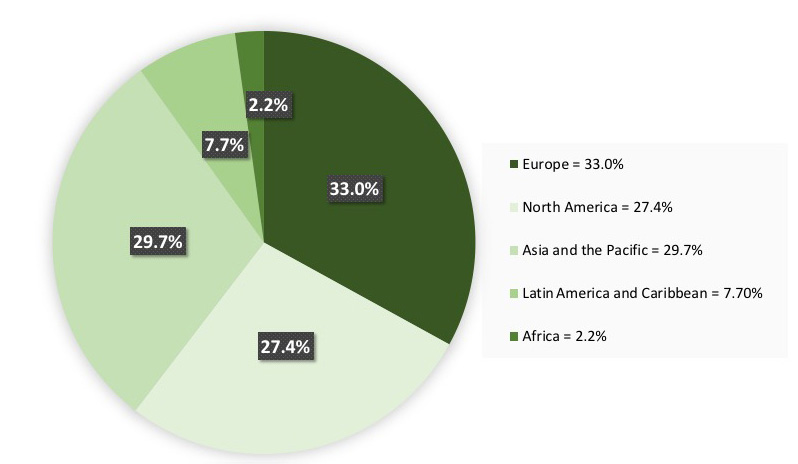

Global production of sawnwood in 2015 totaled 452 million m3. Again, Europe was the largest producer followed by Asia and the Pacific and North America (Figure 1-3). Twenty-nine percent of sawnwood entered international trade, with Asia and the Pacific and Africa being net importers. Europe and North America were the largest exporters. The countries with the largest production of sawnwood are the US, China, Canada, the Russian Federation, and Germany.

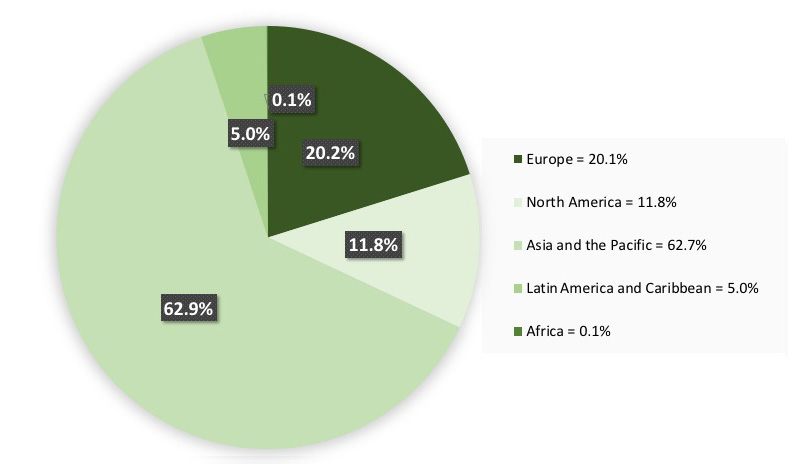

Global production of wood-based panels totaled 399 million m3. Asia and the Pacific accounted for nearly two-thirds of global production (Figure 1-4). Global trade of wood-based panels amounted to 21% of total production. Europe and Asia and the Pacific accounted for most international trade in this product category. China, the US, the Russian Federation, Canada, and Germany make up the five top producers of wood-based panels.

Global production of fiber furnish totaled 407 million tons in 2015. Asia and the Pacific was the leading producer, followed by North America and Europe (Figure 1-5). Approximately one-quarter of fiber furnish entered global trade with Asia and the Pacific as the only net importing region and North America as the largest net exporter. The top five countries producing fiber furnish were the US, Canada, Brazil, the UK, and Japan. It is important to note that recovered paper is an important component of these statistics.

1.3 Major Societal-level Developments

There are many societal developments impacting forest products markets. Here we concentrate on: globalization, population growth, sustainable development, and growth of the circular bioeconomy.

1.3.1 Globalization

Globalization is not one issue or phenomenon, but a series of societal trends that together are driving the integration and interdependence of the world’s markets and people. In a basic sense, globalization is the mobility of information, products, people, and investments.[8] Today, globalization is a well-known phenomenon that has significant impacts on the individual consumer, including the availability of information, availability of products, exposure to other cultures, etc. People are extremely mobile and international travel is common. Mobility exposes people in all societies to the peculiarities and experiences of others. The flow of information and people has begun a process of homogenization that is causing societies and cultures to become more similar over time.

Global companies/brands illustrate the phenomenon of globalization well. Where have you been lately that you couldn’t find a McDonalds? This is a simple example of the homogenization of societies; eating at McDonalds is a common experience for many people around the world. Global companies like McDonalds, along with the impact of television and the Web, result in a convergence of ideas and experiences.

In the not-so-distant past, people in developing countries had little understanding of the degree of affluence and consumption in other parts of the world. With information readily available via the Web, these people clearly know what is happening in other countries and often wish to emulate the consumption-focused lifestyle. This desire has obvious political ramifications, but perhaps more important is the potential consumption of resources that will be needed to satisfy these desires. World population and per capita consumption will grow in the coming decades, resulting in important ramifications for governments and society as well as the forest industry.

1.3.2 Population and demand growth

Our current global population of 7.6 billion is expected to reach 8.6 billion in 2030, 9.8 billion in 2050, and 11.2 billion in 2100. China and India have the largest populations at 1.4 and 1.3 billion inhabitants, respectively. India is predicted to surpass China in 2024. Nigeria is the fastest growing country globally and is expected to become the third largest country in population around 2050.[9] Adding nearly four billion people to the planet has major implications for both the supply and demand situation for forest industry companies. Fast-growing countries tend to have younger populations, especially compared to countries like Italy and Japan that have declining populations. These demographics have obvious implications for the products that forest industry companies target to various markets.

1.3.3 Sustainable development

As society has developed and the basic food and shelter needs of citizens have been met, the collective focus of society has evolved to rest on the need for a healthy environment. A key manifestation of this evolution has been a focus on sustainable development. The Brundtland Commission defined sustainable development as, “Development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs.” A basic premise of sustainable development is that it applies to three realms, economic, social, and environmental. This three-part thinking has dramatically impacted developments in the forest industry. For example, forest certification standards have developed that require performance in each of these three areas before a forest area can be certified. Overall, the sustainable development issues facing the forest sector have been predominantly associated with the environment, but social issues have become more prominent in recent years, especially as large companies in developed countries have begun investing in developing countries.

An increase in attention by society on human-caused environmental impacts means consumers are increasingly focused on “green” products. It also means companies have a near constant effort to reduce environmental impacts in order to be seen positively within a society that has evolving demands regarding environmental performance.

1.3.3.1 The Greening of Markets

Consumers are increasingly interested in environmentally friendly, or green, products. A leading development in this area has been organic food. In the early 90s organic food was still a niche or even a fringe market. As market demand grew, mainstream grocery stores also began offering organic food. Today, organic food is quite common. Other food certification systems have been developed such as Fair Trade that focus more on the social aspects of the food source.

Other green products have also proliferated in the market. Early entrants were natural cleaning products. Today, a broad array of products make green claims and products designed for green consumer are common. Electric cars are an interesting example since cars, in general, have so many environmental impacts. However, cars such as Tesla are seen as highly environmentally friendly, to the point of becoming common in some marketplaces such as Norway. Even oil companies have jumped on the green bandwagon, despite all the negative environmental implications of the exploration, extraction, and use of petroleum products.

A desire for a greener built environment by consumers, but especially by architects, is a positive development for wood products companies. Government procurement policies play an important role in creating demand for greener products and corporate buying policies also have a positive influence. Demand for certified wood and paper products has been significantly impacted by the buying policies of large companies such as The Home Depot. Specific to the built environment, wood is seen positively compared to concrete and steel. Various green building certification programs recognize wood as an environmentally preferable material, especially when it is sourced locally. There are efforts, for example, in Oregon to build on this local sentiment when it comes to wood products. The Build Local Alliance works to build local markets for locally grown wood products.

An environmentally conscious consumer creates opportunity for forest industry companies. Because wood is renewable and generally processing of wood is low energy intensive, companies are positioned to offer up environmentally preferred options and create sustainable competitive advantage.

1.3.3.2 Climate change mitigation

Despite the current US policy indifference to climate change and carbon issues, concerns over climate change are having major impacts on both supply and demand for forest industry companies. Many countries have agreed to reduce their carbon footprint (amount of CO2 they release to the atmosphere). The Paris Agreement, a collaboration among many world governments is the most significant mechanism for this. Based on this and earlier commitments, major policy changes have been implemented in most countries. Still, response to climate change is a highly contentious issue and there is much disagreement in the international community regarding the right path forward. Policy uncertainty presents challenges to the forest sector, but also important opportunities since forests can play an important role in potentially mitigating climate change.

As with green products, a positive carbon story can differentiate forest industry companies and their products. Effectively communicating that story can provide an advantage in the market.

1.3.4 Advent of the Circular Bioeconomy

The circular bioeconomy represents a paradigm shift away from a fossil-based economy, helping society to exist within planetary boundaries.[10] There is much yet to materialize with respect to how the forest industry will embrace the opportunity.[11] As purveyors of renewable materials, forest sector companies are positioned to capitalize on current marketplace trends. It has been suggested that companies “must” transform to enter these new markets.[12]

The development and growth of the circular bioeconomy presents an opportunity for forest sector firms to diversify product offerings and escape reliance on stagnant markets for mature products. Opportunities exist in traditional market spaces such as solid and engineered structural wood products for housing or non-residential construction as well as liquid fuels, chemicals, bioplastics, nanocellulose, etc.[13] Coming from bio-based raw materials, these products are perceived to have a superior environmental profile compared to alternatives, especially products from petroleum. Arguably, all forest sector products are bioproducts and therefore the companies producing them are already at the heart of the circular bioeconomy. The social and political changes driving growth of the circular bioeconomy give forest industry products a new edge in traditional markets and forest industry companies new opportunities across a host of new products. Firms that fail to embrace the opportunity of the bioeconomy may find it increasingly difficult to maintain profitable operations.[14]

Any effort to make products more environmentally friendly is a step toward the circular bioeconomy. Non-formaldehyde-added adhesives, reduced density fiberboards, and cellulose-based insulations are examples. Developing new products with a design for environment philosophy, minimizing environmental impacts over the entire lifecycle of the product is a more direct way for forest sector companies to play a more significant role in a circular bioeconomy where products are actively re-used, repaired, refurbished and recycled. Improved marketing practices may be one aspect needed for companies to make the successful jump to the bioeconomy.

1.4 The Context of the forest industry

The forest industry has changed significantly in the last several decades and the pace of change shows no signs of abating. Many changes have been driven by a long span of poor profitability by many companies in the industry. This poor profitability played a part in consolidation of the industry as companies attempted to focus on specific product segments and internal core competencies. The Great Recession that began in 2007 had a dramatic impact on the industry such that many industry observers see it as a totally new landscape after recovery.[15] Finally, the industry is improving its approach to customers and developing an increased level of marketing sophistication.

1.4.1 Profitability Woes

For many years the forest industry suffered from poor profitability performance. Generally, the industry targets a 12% return on capital employed, but the value was often closer to 5%, a level considered to be actually destroying value or capital.[16] Many industry analysts attributed the poor performance to the fragmented nature of the industry. Fragmentation often results in overcapacity, lack of price discipline, and an overall inability to influence trends in the industry.[17] Because of its fragmentation and capital intensity, there is a tendency for the paper side of the industry to be highly cyclical.

- When demand and prices are high, each company in the industry wants to be part of the growth to meet future demand. Accordingly, they choose to add capacity. Because paper production is highly capital intensive, capacity is added in large chunks.

- When the added capacity comes on line, supply outstrips demand and prices fall. Prices don’t begin to climb until demand has caught up with the added capacity. Meanwhile, companies are faced with low prices and overcapacity along with the debt they incurred to create the capacity. With a production mentality they try to produce their way out of losses further exacerbating the overall industry’s problem.

- In a basic sense, companies participating in this “vicious loop” are succeeding in maintaining market share at the expense of healthy profits. Companies that invest at the bottom of the cycle would be perfectly positioned to capitalize on high demand and prices, but few are able to pull this off.

Consolidation has resulted in significant market shares being held by one or a few companies. Today, companies often shut capacity down during the down cycle, resulting in better supply management across the industry and potential for evening out the cycle. Although the solid wood side of the industry does not face the same dynamics, it is even more fragmented than the paper side of the industry, and consequently, individual firms have very little influence on the overall marketplace.

One positive following the Great Recession (see below) has been a relatively long run of good prices and relatively stable demand growth on the wood products side of the industry. Slack resources available via positive prices creates a situation where companies are more able to invest in marketing and improve their marketing strategies, structures, and functions.

1.4.1.1 The Great Recession

The global recession that began in 2007 had a dramatic impact on the forest sector. The housing bubble in the US created market imbalances across the globe. For example, significant volumes of sawnwood were being imported from Europe in order to feed the housing frenzy. When US housing starts fell from over two million to less than a half million, it was not just the US producers and intermediaries that felt the impact. The world’s largest export destination was relatively quickly off-line to international suppliers and they were scurrying to find new markets. Thousands of jobs were lost in the North American forest sector and hundreds of companies went out of business. As an example of the reduction in the marketplace, the ten largest US homebuilders produced nearly 300,000 homes during the peak year of 2006. By 2009 this value had fallen to about 85,000 homes.[18] The collapse of the US housing market was also challenging for Canadian producers since the US is such a significant market. Sawn softwood consumption in North America fell by nearly half between 2005 and 2009. For the first nine months of 2008, operating rates for Canadian lumber mills averaged only 63% and OSB averaged 50%.[19] One outcome of the housing collapse is that forest products companies have begun to focus on markets outside of residential housing. Commercial buildings and various industrial markets (vehicle bodies, packaging, etc.) are examples.

1.4.1.2 Industry consolidation

Globalization has had its impacts on the industries that serve as major customers of the forest industry. For example, the publishing industry has seen consolidation with the largest companies operating around the globe. Because these customers operate on a global basis, they are looking for suppliers that can meet their needs regardless of location. In other words, they are looking for their suppliers to become global along with them. The home building and do-it-yourself (DIY) retail sectors have also seen consolidation and the development of huge companies.

The logic of consolidation is to gain sufficient market share to effectively influence market forces, especially pricing. Because of the nature of the marketplace and the cost of building new capacity, it often is more economical to buy existing capacity. There is some evidence that in commodity industries with four or fewer competitors, pricing will be impacted even without overt collusion. On the other hand, in situations of more than six competitors, the market is characterized by perfect competition.[20]

Consolidation has left three major paper producing companies in Finland, where only about 30 years ago there were more than 20 companies. Other countries have not progressed this far along the consolidation path, but mergers and acquisitions have been common during recent years. Much of the recent consolidation is not about getting bigger, but about growing in those sectors where the companies have core competencies. A narrower focus within specific sectors provides new options with respect to implementation of marketing both from the perspective of economies of scale and general ability to invest in market development.

1.4.2 Increased environmental responsibility

1.4.2.1 Environmental management

As ENGOs pressured the forest industry and sustainable development came to the forefront of the business agenda, companies looked for ways to manage their environmental impacts. During the 90s it became common for companies to implement environmental management systems. The basic goal of the implementation of these systems was to identify and manage impacts to the environment and to continually improve performance. By the end of the 90s, the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) 14000 series of standards had been developed, and large companies in all regions of the world were actively engaged in implementing ISO 14001 for both their production and forestry operations. Developments in forest certification went hand-in-hand with developments in environmental management. The practical objective of forest certification is to guide forest management in a market-led manner in an economically, ecologically, socially, and culturally sustainable direction. In order to achieve that objective, there must be a close link to marketing. Thus, certification may act as:

- A tool for promoting sustainable forest management– For example, government authorities may use certification to support their forest or environmental policies.

- A tool for satisfying the needs of customers– For customers, certification indicates that the product comes from a well-managed forest. Certification helps consumers make choices and supports the attainment of sustainable development regarding consumption.

- A tool for marketing –Marketing adapts the company to its business environment, and turns prevailing trends and customer needs into business opportunities. If sustainable development is one of the values of an enterprise, it makes sense to integrate certification with marketing decisions.[21]

Environmental labeling is a mechanism to allow consumers to make product choices based on the environmental impact of a product. The premise is that an ecolabel or environmental label will provide an incentive for producers to minimize environmental impact, because they will receive some form of marketplace benefit. A range of environmental labels exists both inside and outside the forest industry. The Forest Stewardship Council label is quite common on catalogs, direct mail, and retail wood products. With respect to forest certification, an ecolabel communicates the nature of the forest management from which the wood product originated. However, forest certification ecolabels do not say anything about other parts of the life cycle. Environmental product declarations (EPDs), a sort of environmental impact documentation, is becoming more common for forest industry products. EPDs are described further in Chapter 2.

1.4.2.2 Corporate Responsibility

The role of business and the way it is perceived by society have undergone changes throughout history. Over time, awareness of the impact of business and its interplay with societal and environmental concerns has emerged, along with parallel growth of socio-regulatory pressures. This evolution of business and societal concern has led business to gradually assume increased responsibility and consideration for both social and environmental issues, typically beyond what is required by legislation. This response is commonly referred to as corporate social responsibility or corporate responsibility (CR).

CR has deep historical roots. For example in Finland, in the early days of industrialization, forest industry companies could take care of the versatile individual and social needs of their work force. Companies provided housing for their employees. A company also could have its own hospitals, kindergartens, schools and even church. Later, society began to take care of these services. Nowadays when the environmental consciousness has strengthened, environmental responsibility is one of the biggest demands placed on industry. Employment is another big issue.

The concept of sustainability has permeated society and because the forest sector is so closely tied to a highly recognized resource that is important to the average citizen, companies have been pushed to recognize that they are responsible for more than merely providing profit to shareholders. Several multilateral organizations have tied CR to sustainable development in that companies should contribute to the objective of securing sustainable development. Many advocate the pursuit of global CR standards, yet there is also recognition that a context-specific approach is likely to be both more feasible and farther reaching. An example of context specificity is that U.S. companies generally place more emphasis on environmental issues while companies in countries such as Brazil may place more emphasis on social issues. Societal expectations of business vary from one country/location to another.

Globalization, advances in communication technologies, and the emergence of ethical investment opportunities all contribute to increased attention on CR. Easy access to detailed information on corporate activities has increased transparency and heightened public awareness regarding the varied impacts, both positive and negative, of companies worldwide. In turn, this awareness has aided citizens and activists seeking corporate change, and boosted global discussion about CR and its adoption by companies. To varying degrees, globalization is resisted by societies concerned with the social and environmental implications of global companies. Therefore, it becomes increasingly important for organizations to proactively respond to social and environmental issues in order to ameliorate societal concerns.

One area that forest industry companies are heavily focused is on climate change. As one CR activity, forest industry companies have begun to quantify their carbon balance and are working to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions. Some companies have committed to specific emission reduction targets. While forest certification was arguably the hottest issue facing the industry in the 90s, climate change strategies and the impact of climate change policies are at the top of the forest industry agenda for the foreseeable future.

1.4.3 Industry 4.0

It is said that industry is experiencing the fourth industrial revolution, when digital manufacturing, big data, robotics, etc. are changing the reality of the manufacturing industry. The Boston Consulting Group outlines nine technologies transforming industrial production: big data and analytics, autonomous robots, simulation, horizontal and vertical system integration, the industrial internet of things, cybersecurity, the cloud, additive manufacturing, and augmented reality.[22] Employing Industry 4.0 technologies will enhance forest products manufacturing and, in turn, create new possibilities for effective forest products marketing. Improved utilization of Internet of Things can help assist improved supply chain operation, thus enhancing both the reliability and profitability of the entire supply chain.

1.4.4 An increased marketing sophistication

The forest industry has traditionally been production-oriented rather than customer-oriented, causing companies to maximize production even when inappropriate. By focusing on production rather than customers, the industry has failed to capitalize on the improved performance that can result. However, this approach to business is changing. Rhetoric in company annual reports indicates that companies are striving to become more customer-oriented rather than production-oriented. Other indicators of a move toward a customer focus include the following:

- A concentration on customer relationships and relationship marketing

- Increased use of branding

- Embracing new tools of management and marketing (supply chain management, e-business, etc.)

- Dealing with customers directly more often, rather than through intermediaries

- Organizational changes in production and marketing

1.4.4.1 Servitization

Provision of services is becoming an increasingly important component of what forest industry companies offer to their customers[23] (see Total Product in Chapter 4). To remain competitive, it is no longer sufficient to only provide a physical product. Customers require services ranging from in-depth design to basic add-ons such as vendor managed inventory. These services allow the customer to dedicate their resources to their own manufacturing operations rather than things like inventory management. RedBuilt, a US engineered wood products manufacturer, offers engineering services to help customer design projects using RedBuilt products. The company has also begun sourcing complementary products such as solid sawn lumber so that they can provide their customer a full package of wood products necessary for a given project.

1.4.4.2 Value added

As companies evolve away from a production and commodity mentality, they begin to work toward adding value to their products both through processing and marketing. For example, Finnish Sawmills have dramatically increased the proportion of specialty and custom-made products in their total production. Instead of making standard lumber they are making products that meet the specific needs of sectors, such as for the furniture industry or for individual customers. Branding, a marketing tactic designed to assure customer loyalty and increase product value, has grown significantly in the forest industry.

Along with the efforts of individual companies, governments have become interested in promoting the processing of raw materials within their borders, primarily for reasons of employment and economic development. Part of this attraction is a direct result of the loss of employment in the primary industries. Most countries are now processing more raw materials and adding more value domestically, rather than exporting logs or unprocessed raw materials. Governments of producing nations are providing incentives and exerting pressure to capture the value-added process within their domestic forest industry. In the US there is a complete ban on exportation of logs coming from Federal forestlands. In Indonesian, production of plywood increased from 107,000 m3 in 1975 to 9.3 million m3 in 1990 based largely on Indonesian government policy providing incentives and subsidies to develop this segment of the industry.[24]

1.5 Why all this matters

Many of the major developments in society suggest a positive future for marketers of forest products. A growing global population means steady market growth for most products into the foreseeable future. There is an increased focus on transition to a circular bioeconomy. Because of the positive environmental profile of most forest products, the societal focus on sustainability should benefit wood products. For those companies still owning forests, carbon sequestration and sales of stored carbon may open up totally new markets and income streams. A globalized world means myriad markets available to the astute forest products marketer.

There are also a number of challenges presented by the changes taking place in society. Environmental concerns will likely further constrain supply of roundwood as additional forest area is removed from potential harvest. Although the growth in plantations will likely fill most of the potential gaps, supply constraints could definitely impact competitiveness. While globalization means enhanced access to markets, it also means exposure to a wider set of competitors. Industry sectors such as US furniture have already experienced the negative impacts of highly aggressive global competition. The push for sustainability and focus on climate change can result in perverse market forces that could have significant negative impacts for forest products marketers. Already in some regions the push to utilize biomass for energy is resulting in supply competition with pulp and paper as well as composite board mills. In some cases, the biomass for energy market can pay higher prices for raw materials because of government incentives and subsidies. It is a very open question what the trade policies of the Trump Administration will do to forest products markets.

The effects of societal changes and an evolving forest sector will have very different impacts depending on the context within which an individual company operates. For example, globalization and consolidation of markets presents a positive scenario for largest global forest products companies. However, it also presents an opportunity for the smaller, regional companies because the global companies are so large that they may not bother themselves with smaller markets. Regional companies can thrive by serving the small “left over” markets and by offering specialized products.

So, the changes taking place in society have both direct and indirect impacts on the implementation of marketing and business practices. The remainder of this book addresses how the practice of marketing should and does take place in the forest sector, all within the context of the industry as described above.

1.6 Chapter Questions

- Where are global forests located?

- What regions of the world are major producers of each product category?

- How are major societal trends changing the world we live in?

- How is the forest industry evolving to deal with major societal changes?

- FAO. 2018. State of the World's Forests. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Rome, Italy. 118 pp. ↵

- FAO. 2018. State of the World's Forests, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Rome, Italy. 118 pp. ↵

- G.V. Villavicencio. 2009. Opportunities and Limitations for Community Forest Enterprises, Case of TIP Muebles, Oaxaca, Mexico. MS Thesis. Oregon State University. 146 pp. ↵

- FAO. 2006 Glabal Planted Forests Thematic Study: Results and Analysis. By A. Del Lungo, J. Ball and J. Carle. Planted Forests and Trees Working Paper 38. Rome. (Available from www.fao.org/forestry/site/10368/en). ↵

- C. Jürgenson, W. Kollert, & A Lebedys. (2014). Assessment of Industrial Roundwood Production from Planted Forests. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Rome, Italy. 30 pp. ↵

- FAO. 2009. State of the World's Forests 2009. Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations. Rome, Italy. 168 p. ↵

- AO. 2016. 2015 Global Forest Products Facts and Figures. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Rome, Italy. 16 pp. ↵

- Anonymous. 2001. Measuring Globalization. Foreign Policy. January/February:56-65. ↵

- UN. 2018. World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision. https://www.un.org/development/desa/publications/world-population-prospects-the-2017-revision.html. Last accessed on July 13, 2018. ↵

- L. Hetemäki, M. Hanewinkel, B. Muys, M. Ollikainen, M. Palahí, & A. Trasobares. 2017. Leading the way to a European circular bioeconomy strategy. From Science to Policy 5. European Forest Institute. https://www.efi.int/files/attachments/publications/efi_fstp_5_2017.pdf ↵

- A. Roos & M. Stendahl. (2015) The role of the forest sector in the emerging bio-economy. In, Forests, business and sustainability. Panwar R, Hansen E, Kozak R (eds). Taylor & Francis Books. ↵

- V. Chambost, J. McNutt, & P.R. Staurt. (2009) Partnerships for successful enterprise transformation of forest industry companies implementing the forest biorefinery. Pulp & Paper Canada. 110(5):19-24. ↵

- Z. Cai, A.W. Rudie, N.M. Stark, R.C. Sabo, & S.A. Ralph. (2014) New Products and Product Categories in the Global Forest Sector. In, Hansen E, Panwar R, Vlosky R (Eds.). The Global Forest Sector: Changes, Practices, and Prospects. CRC Press. ↵

- P. Söderholm & R. Lundmark. (2009) Forest-based Biorefineries. Forest Products Journal, 59(1/2):7. ↵

- R. Panwar, R. Vlosky, & E. Hansen. 2012. Gaming competitive advantage in the new normal. Forest Products Journal, 62(6), 420-428. ↵

- PWC. 2010. Global Forest and Paper Industry Survey. PricewaterhouseCoopers. Vancouver, British Columbia. 332 pp. ↵

- PWC. 2000. Global Forest and Paper Industry Survey. PricewaterhouseCoopers. Vancouver, British Columbia. 42 pp. ↵

- Wood Markets. 2010. Supply Chain Impacted by Recession, "Business as Usual" Was Not an Option. Wood Markets Report. 15(2):4-5. ↵

- Wood Markets. 2008. North American Dilemma, Wood Product Commodities in Trouble. Wood Markets Report. 13(10):1-2. ↵

- Economist. 1999. Commodities Get Big. The Economist. 352(8134):47-48. ↵

- FCC. 1997. Development of Forest Certification in Finland. Publications of the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry 65a/1997. ISSN 1238-2531. ISBN 951-53-1460-7. ↵

- M. Rüßmann, M Lorenz, P. Gerbert, M Waldner, J. Justus, P. Engel, & M. Harnisch. 2015. Industry 4.0, The Future of Productivity and Growth in Manufacturing Industries. The Boston Consulting Group. 15 pp. ↵

- P. Pelli. 2018. Services and industrial development: analysis of industrial policy, trends and issues for the forest-based sector. Journal of Forest Economics, 31, 17-26. ↵

- M.J. Lyons. 1995. Export Marketing of Plywood from Indonesia. Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations. Rome, Italy. ↵