Chapter 4: Strategy and Strategic Planning

After reading Chapter 4 you should understand the following:

- The meaning of strategy and how the approach to strategy has changed over time.

- The relationships and differences among corporate, business, and marketing strategy.

- The concept and process of corporate strategic planning.

- The role of the product in a marketing strategy and the many aspects of the product that can be used to tailor the strategy.

- The role of customer choice in marketing strategy and the logic of choosing customers.

- The role of market area choice in marketing strategy and ways to choose market areas.

- Core competencies as part of marketing strategy.

- The interrelationship among product, customer, market area, and core competency decisions.

- The logical connections among strategies, structures, and functions as outlined in the Integrated Model of Marketing Planning (IMMP).

The concept of strategy originates with the art of warfare. According to Webster’s Dictionary, strategy can be defined as, “the science or art of combining and employing the means of war in planning and directing large military movements and operations” or “a plan, method, or series of maneuvers or stratagems for obtaining a specific goal or result.” Companies use strategy and the process of strategic planning to reach their economic, social, and environmental goals.

4.1 The Concept of Strategy

4.1.1 Historical Development of Strategic Planning

Strategic planning evolved from the process of annual budget planning in the 1950s. In the 1960s, fast-growing demand caused companies to extend their planning horizon beyond an annual basis, making long-range planning necessary. For example, when Rich[1] wrote his textbook on forest products marketing, he referred to long range planning and business strategy. In long range planning, the future is predicted through extrapolation of historical growth.[2]

Dramatic changes in the business environment, such as the oil shocks of the 70s, required more sophisticated approaches to systems of management. Next came strategic planning where predictions of the future were no longer primarily based on the past.[3] With this new approach, managers began looking for ”vague signs” or potentially important trends that might impact their operations. When one of these vague signs was identified, its development was followed and its impact was considered in the continual process of strategic planning.

Prior to the the 1980s, most planning was done at the corporation’s executive level. During the 80s, strategy development shifted to operating managers, and strategic management became the common term.[4],[5] In the 1990s a common term was strategic thinking. Strategic thinking is discovering novel, imaginative strategies and envisioning potential futures very different from the present. In other words, strategic thinking is higher order thinking that should take place to explore potential directions for the company, and strategic planning is the operationalization of those ideas. These two concepts combine to form strategic management.[6] Scenario planning is a tool for enhancing strategic thinking. Like much of strategy, its roots are in military applications but have more recently been applied in business settings. Scion in New Zealand has used scenario planning to envision the future of the built environment in Australasia (Example 4-1).

Example 4-1: Scenario Planning in Australasia

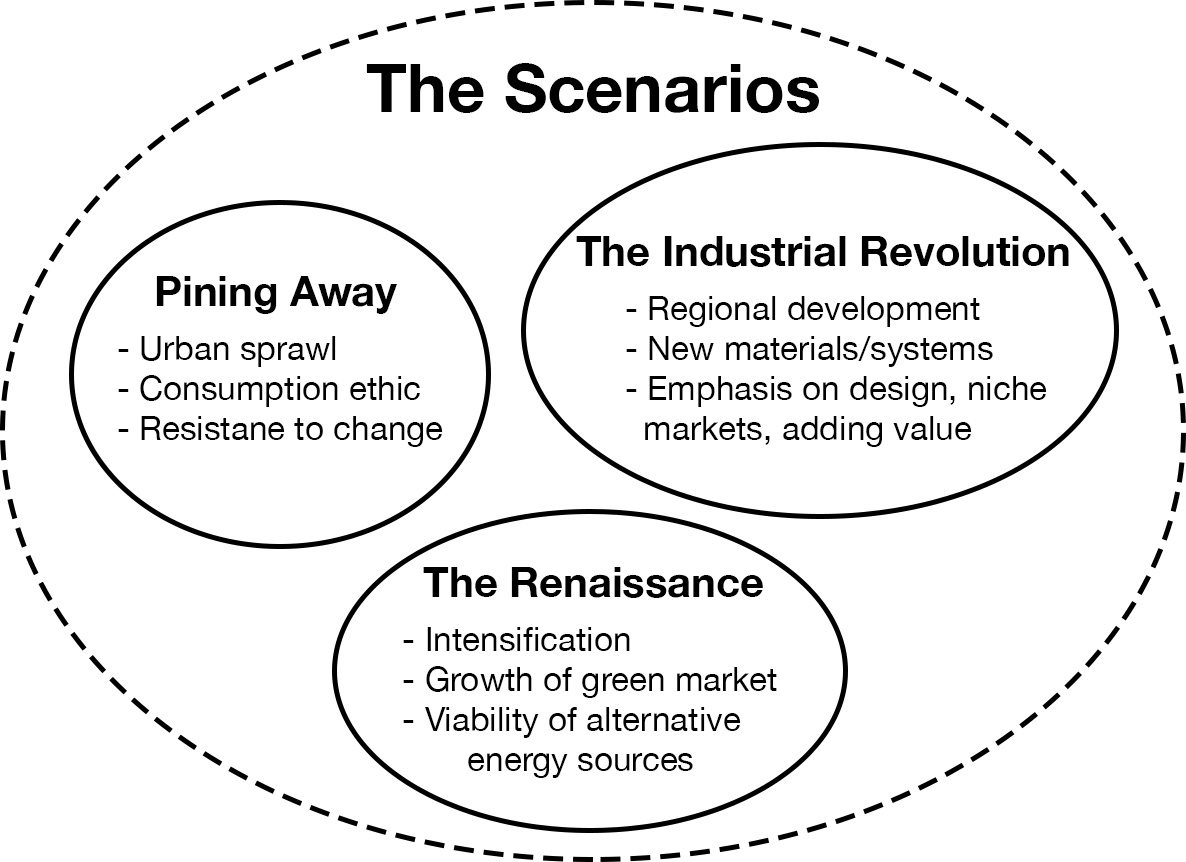

Scion (formerly Forest Research) in New Zealand has used scenario planning in several projects to help its wood industry envision potential futures of housing in the region. One project created three visions for the future urban built environment in Australasia. The project team used existing literature, personal interviews, and group interviews to gather information about the social, economic, environmental, and technological aspects of society. With this information the team created and described three different scenarios of the future: Pining Away, The Industrial Revolution, and The Renaissance. Each scenario is described through the story of an older woman who was a city planner, her husband who was a master carpenter, and her son, a chemical engineer. Using these characters, each scenario is described via a short story of the situation with the family in about the year 2015. The team suggests that the scenarios are not exactly predictions of the future, but should be used as a set when making strategic decisions. In other words, the scenarios are a way of taking complex, and extensive information and combining it in a way that can be digested by strategic planners and effectively utilized in planning processes. An example of one scenario, in its original text, is provided below.

The Renaissance

Jessie stepped out of her apartment building and smiled up at the sun. Taking a deep breath, she smelled the cool air that always resulted from a brisk southerly storm. She enjoyed these refreshing interludes in the increasingly warm and muggy weather. Feeling a rare wave of youthful energy, she headed off to the local shops with a spring in her shuffle.

Taking a short detour through the new sculpture garden, Jessie sat for a while on a park bench and marveled at the transformation. She remembered when this area had been a car park; now it was a pleasant oasis among a cluster of townhouses. Jessie had seen a major turning point in industrial history during her lifetime, and as a town planner she had helped to shape many of the changes. At the turn of the twenty-first century, she and her colleagues had expected consumers to follow green market trends, but nothing had prepared them for the rate at which public consciousness had changed.

In the past, consumers always had a remarkable ability to disregard most environmental problems. When Jessie was young, she remembered, there was concern about pollution, climate change, and resource depletion, but efforts to address these problems never seemed to get anywhere. Finally, a chain of events shifted public opinion to a critical mass and Government intervention was demanded. Hydro lakes slowly became depleted through drought, natural gas fields diminished, and oil prices fluctuated wildly due to supply difficulties. Climatic disasters became common and a crippling cyclone caused widespread blackouts to the city along with major disruptions to transportation. Graced with a mandate for radical change, Smart Growth planners such as Jessie seized the opportunity to rebuild a different type of community.

Other countries were experiencing similar events, but New Zealand and Australia were able to effect change more quickly due to relatively small populations. As a result, Australasia retained significant appeal as a “lifestyle frontier” to migrants and, although international tourism had declined due to rising oil prices, more people came here to live, making urban intensification had been achieved through strong local government leadership, including initiatives such as subsidised public transport systems and multi-unit development along transport corridors. Rural zoning limitations were also tightened to contain urban sprawl so that those wishing to live outside the major cities tended to favour satellite towns within the region. Jessie hadn’t forgotten all the difficulties and challenges they had faced, but tighter stronger communities eventually emerged.

Looking back, it was almost frightening to recall the economic risks they had taken. High transport costs, non-tariff barriers, and the implementation of carbon taxes gave rise to a major push towards self sufficiency, primary production, and a strong service industry. As the population had continued to grow, so did the need for more energy and this led to rapid advancement in sustainable energy technologies. Jessie’s son, Kevin, was currently working as a chemical engineer at the bio-fuel plant constructed near the city. As one of the largest and most productive of its type in the world, it had helped to set the standard for alternative energy supply.

The increased cost of transportation meant the price of imported consumer goods went up, so there was an upsurge in local processing. Manufacturers close to the market could suddenly compete with goods produced by large international producers, and this fostered the development of local businesses around a strong green economy. Within a relatively short time, certification and green branding had become compulsory, sustainable production was strictly enforced, and socially responsible businesses prospered.

While the mass media continued to entice consumers, it seemed to Jessie that people had become disillusioned by rampant materialism. As individuals sought to develop a sense of place and identity in the global context, there had been significant growth of religious, cultural, and community groups. Jessie thought this may have been a reaction to the dumbing-down effects of globalism. Or maybe, with ever-increasing numbers of elderly people in the population — like herself — society was just growing up.

As she stared across at a beautiful wooden sculpture, Jessie reflected on how the new society was built on a strong sense of tradition and creative expression. When it came to the crunch, people had turned to their roots for the answers and the economy found its strength in the land. The value of producing food and fibre in a world of increasingly scarce resources had been realised and primary producers capitalised on their comparative advantage by building a strong knowledge economy around agriculture and forestry.

Jessie had experienced this trend most keenly through the work of her late husband, Jim. As a master builder he witnessed many changes after building standards were tightened to ensure higher energy efficiency. Much to Jim’s approval, solid wood had provided the best solutions for construction. Not only did it have better thermal insulation properties than other materials, it was also more energy-efficient to produce. An oversupply of radiata pine resulted in timber being used in a variety of applications, and Jessie had been amazed at the range of ideas borne of necessity. One of Jim’s favourite projects had been the construction of concept homes demonstrating energy efficient and stylish use of wood-based construction systems.

Diminishing landfill space also prompted more use of wood and other organic materials as local bodies pushed for zero-waste. Laws had made the cost of demolition almost prohibitive and so building systems evolved around durable low-maintenance exteriors and easily modified interiors to suit individual tastes. Jim had also been heavily involved in the refurbishment of existing housing stock to meet new energy codes. Jessie smiled to herself as she recalled how former State-housing tracts had become trendy suburbs. Their construction from native timber, combined with clever refitting, had made them desirable to an extent that would never have been believed 50 years ago.

Still, changes like these had been par for the course. Looking back, it amazed Jessie how well people had adapted when circumstances dictated it. A bird caught her eye as it flitted around the sculptures and she smiled when she noticed a nest tucked among the artistic curves. Humans may have been slow to learn the art of compromise, but they were getting there. How could they not, when nature provided such good role- models?[7]

It is important to note that individual companies also evolve through the stages listed above. As a first step, companies develop budget plans on an annual basis. As they gain experience in the marketplace, they begin to forecast beyond an annual basis and move toward long range planning. As the expertise of company personnel grows, the tools for true strategic planning and strategic management are developed.

4.1.2 Defining Strategy and Strategic Planning

Strategy is a nebulous concept with multiple definitions and little consensus regarding its makeup. One reason for this difficulty is that the term ”strategy” often refers to different hierarchical levels, such as the corporation as a whole, the strategic business unit, and the product (note that for smaller companies, the corporate and strategic business unit levels may be the same). Strategy is also used in a variety of contexts such as marketing, distribution, or communication and ironically, marketing researchers often do not have a common understanding of strategy.[8] Although it is a critical part of strategy research, the strategy concept has no universally accepted definition.[9]

A major difficulty in implementing marketing strategies is that the current definitions are exceedingly vague and provide no guidance for the strategic planning process or the decisions that must be made. Our approach is to view strategy in the context of the decisions a manager must make as well as the information needed to make those decisions. In this way, we begin to illustrate the practical steps that occur in a successful strategic planning process. In this text we emphasize the principle that the strategy concept must tell what should be done when making plans and decisions concerning strategies.

In addition to the varying definitions of strategy, there are many schools of thought regarding how the process of strategic planning actually occurs. Academic research has developed along a dichotomy of rational versus incremental planning.[10] The rational school believes that a core group of company managers deliberately formulate strategy. The incremental school claims that strategy emerges within a company through its day-to-day activities. Much of the work from the rational school originates from Ansoff[11], while Mintzberg[12] is commonly associated with the incremental school. Like Mintzberg, Ohmae[13] suggests that “effective strategies do not result from specific analyses but from a particular state of mind, a state in which insight and consequent drive for achievement, often amounting to a sense of mission, fuel a thought process that is basically creative and intuitive rather than rational.” In practice, strategic planning will be unsuccessful unless both of these aspects are incorporated.[14]

When viewing strategy from outside the company, the distinction between these two concepts is not so critical. Even if strategies have not been developed through a logical process as described in the rational school, they can nevertheless be seen in the activities of a company. In other words, even if strategies have not been defined, company activities and their results can be used to characterize strategies.

4.1.3 The General Nature of Strategy

Although there are differences in definitions for strategic planning and strategy, some general features of strategy can be outlined. There are many classifications or definitions of strategy. For example, Niemelä[15] identified the following approaches to strategy:

- Strategy as an atmosphere or a framework

- Strategy as a plan resulting from a formal planning process

- Strategy as a position

- Strategy as a pursuit of competitive advantage

- Strategy as a pattern of decisions and actions

The following review separates approaches to strategy into three simple categories from general to specific. The categories parallel historical development of the strategy concept.

Strategy as a Framework or Atmosphere

Particularly in the 1950s and 1960s, it was very common for firms to view strategy as an atmosphere or framework that influences all the activities of the company. Strategy directs all the decisions made in the company, but it does not define what kind of decisions are strategic. This approach does not define what to do when planning strategies. Instead, it more generally describes norms, attitudes and “the way of thinking” in the company. Thus, the term “strategic” came to be almost synonymous with “important.”

The idea of strategy as a framework can be seen in Figure 4-1, where it is referred to as a tool of management. The functioning of a company is based on its business idea (mission), and is aimed towards specific goals within a framework formed by strategy. Strategies are defined by top management and are based on analysis of internal and external conditions.

For example, in small companies management may not recognize the necessity of defining specific strategies, and may instead form strategies spontaneously as a sum of the targets and principles of action.[16] On the other hand, when strategy develops over a long period, as if by itself, it forms a spirit or atmosphere. The existence of a spirit or atmosphere affects decisions and actions, developing into principles and guidelines by which the long-term goals of the company are to be achieved. The choices made in a company can be described by pairs of concepts like aggressive – defensive, active – passive, or innovator – follower. The atmosphere has also been described with expressions like “production-oriented strategy,” “business-minded strategy,” or “marketing-oriented strategy.”

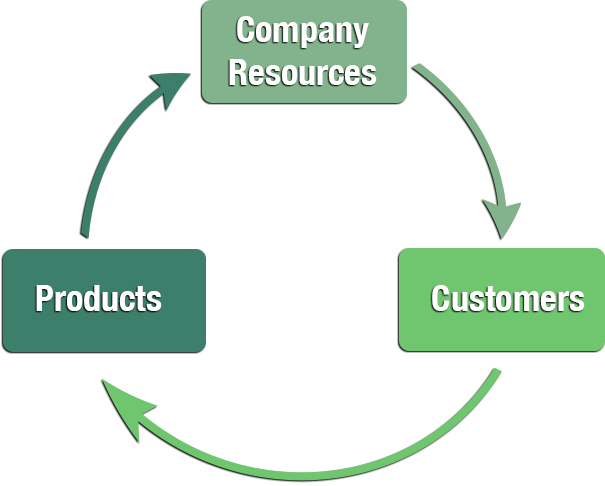

Strategy can be described as laying the groundwork of general principles through which the company tries to secure its competitive advantage, customers, and fully utilize its resources.[17] This demonstrates three cornerstones of strategic thinking: customer attraction, competitor consideration, and company resources development. However, when using a framework concept of strategy, the actual contents of the strategy often remain undefined. The definitions describing strategy as a framework or atmosphere are not operational. Making inferences and decisions concerning strategies require strategy concepts with clear ways of measuring them.

Strategy as an Adjuster Between a Company and its Environment

Kotler defined market-oriented strategic planning as “the managerial process of developing and maintaining a viable fit between the organization’s objectives, skills, and resources and its changing market opportunities. The aim of strategic planning is to shape the company’s businesses and products so that they yield target profits

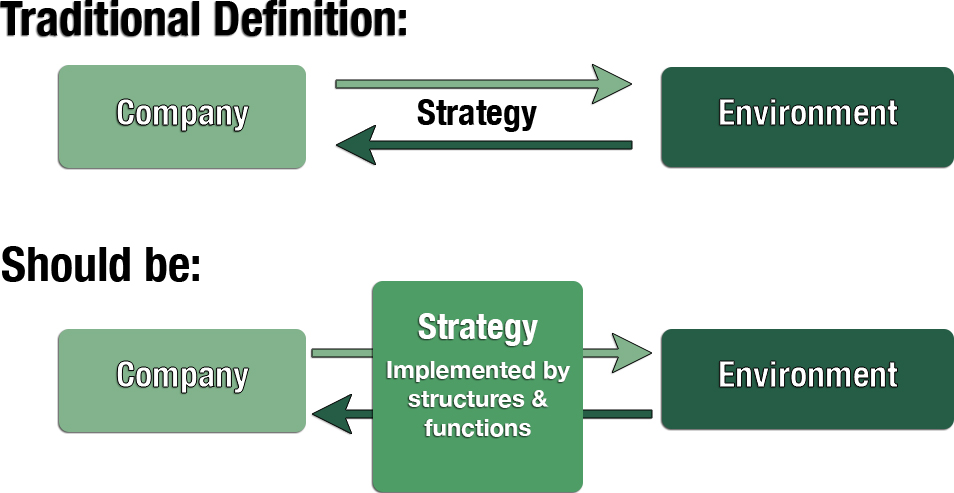

and growth”.[18] Here he emphasizes a basic characteristic of strategy – as an adjuster between a company and its environment (Figure 4-2). This view of strategy has become common since the 1960s, but in most cases, how the adjustment takes place is left unspecified.

The pioneering work of Ansoff[19] has had great significance as the precursor of nearly all analyses of

strategy. The “adjuster” idea was evident in his early work. The “ecological model” of strategic planning presented by Thorelli and Becker[20] demonstrates well the close connection of a company and its environment and strategy as an adjuster. Their basic idea is that every company, like all biological organisms, is dependent upon its environment. The satisfaction of people’s needs is the only reason this environment needs companies. Customers, therefore, have a specific emphasis in this model.

According to Thorelli and Becker[21], goals give direction for setting strategies. The results of everyday activities are the measures of the effectiveness of those strategies. If the results are unsatisfactory, the strategy is not functioning correctly as an adjuster between the company and its environment, indicating that the strategy must be further developed. Although the authors define strategy as an instrument in the adjustment process, they do not define strategy thoroughly. Strategy is said to be the approach or position that a company takes in order to succeed in its actions. Again, this definition is somewhat insufficient because it is not operational, it does not specify what must be done when making plans and decisions concerning strategies.

Strategic position is closely related to the relationship between a company and its environment. A strategy directs a company into a certain relationship or “strategic position” within its environment. A change in the company’s environment forces management to pay attention to its strategic position. Management must then evaluate the product/market combinations with which the company operates.

Strategic positions and ways of change are often described using “Ansoff’s Window,” presented in Figure 4-3.

A company can develop its strategic positioning in four ways:

- By developing current activities (market penetration) the company tries to strengthen the position that its products have in current markets.

- Market expansion (market development) is a way to develop strategic positioning where new markets are sought for current products, either by finding new customer groups or by finding new market areas.

- Product expansion (product development) is a way to develop strategic positioning by offering new products and/or significantly improved current products to current markets.

- Diversification means moving into new business areas, usually by buying companies from areas or fields with better growth possibilities.[22]

Practical examples of these strategies are provided in Example 4-2. Typically, companies follow several at the same time. In fact, pursuing market penetration, market development, and product development at the same time is a sign of a progressive, well-run company.[23]

Example 4-2: Strategic Options as Outlined by Ansoff’s Window

Ansoff’s Window describes the following four methods for developing strategic positioning:

Market Penetration – essentially, market penetration is gaining market share for an existing market. I-joist manufacturers have heavily targeted the Southern California residential floor joist market. Through market penetration, they now hold the dominant market share over the traditional product, solid sawn lumber.

Market Development – In North America after the advent of OSB, structural plywood producers (especially in the West) found themselves at a huge cost disadvantage. Consequently, OSB was quickly taking market share from the major traditional market for plywood, home construction. Because of the cost disadvantage, market penetration was not a viable option. Instead, many companies relied heavily on Market Development. This meant they went after new markets to find customers for their products, such as industrial uses like truck trailer bodies, furniture frames, and pallet decks.

Product Development – it is natural for companies to change their products according to the evolving needs of the customer base. Those companies that do this more efficiently will recognize an advantage. Following the plywood example, the industry also developed new products for new markets. The Big Bin, developed by companies and APA – The Engineered Wood Association is a good example. The Big Bin is an engineered, plywood substitute for 55 gallon plastic and steel drums. These are often used by food processors to transport liquid concentrates such as tomato paste or ketchup. The liquid is contained in a disposable plastic bag. Since the Big Bin is made from panels, it can be dismantled and reused. An additional bonus is that when it is empty, it can be shipped flat, reducing transportation costs.

Diversification – Related diversifications means staying within the broad confines of the industry. This could be, for example, forward integration of a paper company into converting operations for products such as boxes or paper bags. Unrelated diversification is moving beyond the confines of an industry. Diversification was a popular trend in all industries in the 1960s, and forest industry companies invested in a wide array of unrelated businesses. Boise Cascade Corporation invested in a power plant in Cuba and retail lumber yards in the US south; Enso Gutzeit purchased a ferry and started a shipping line. Real estate and housing construction were popular diversification targets. Most of these businesses have since been divested as companies moved to concentrate on core businesses and core competencies.[24],[25]

Ansoff’s concepts of strategic positioning have inspired many followers. For example, portfolio analysis in connection with strategic planning is clearly based on Ansoff’s preliminary work. How portfolio analysis can be used when choosing strategic business areas, products or markets will be described later in this chapter.

Precise and operational definitions of strategy were emphasized by Ansoff[26] when he defined it as a move or series of moves that a company makes. Thorelli and Becker[27] refer to the same idea when stating that the best strategies are those that are based on the use of relative advantage and aim at satisfying precisely defined customer needs. Efforts to precisely define strategy led to consideration of the components which constitute strategy. These components should be well-defined and measurable, as discussed in the next section.

Strategy as Strategic Decisions

Ansoff[28] provided a starting point for the analysis and development of strategy components and strategic decisions. In his opinion, the traditional definitions of the common thread of the company based on mission and the business concept of the firm are too loose and vague. As a replacement, he developed a strategy system composed of the following four components:

- Product/market scope

- Growth vector

- Competitive advantage

- Synergy

Product/market scope is the starting point for the definition of strategy. It defines the product area of the company and the markets to which the products are offered. The growth vector defines the direction of company development. The competitive advantage utilizes the finding of product and market areas, and determines which markets best match the characteristics and strengths of the company, giving it a strong, competitive market position. Synergy is produced by the proper combination of various resources and actions. A successful combination can give the company more possibilities and resources than any of its resources or actions used separately.

The marketing strategy definition we use takes a modular approach. In other words, marketing strategies are made up of several key components, as Ansoff’s work suggests. Careful definition of the product/market area is an essential point of the modular approach. It is worth noting that three of Ansoff’s four strategy components are primarily marketing oriented; product/market scope, growth vector, and competitive advantage. Only synergy refers to the internal use of research and production resources.

According to the concepts of Shirley et al.,[29] the five key decisions that make up a company’s marketing strategy are:

- Customer mix

- Product mix

- Geographical limits of market area

- Competitive advantage

- Goals (evaluation criteria)

This approach stems from the same ideas that Ansoff puts forth, but adds aspects which make the strategic decisions more detailed and operational. When a company defines its strategy, it defines the products, customers, geographical limits of the markets, and competitive advantages on which the use of marketing tools will be planned. It also defines the goals which the company tries to achieve through its actions within these four parameters. All these decisions together put the company in a particular strategic position and define the company’s relationship with its environment. It must be emphasized that although this relationship is defined by strategies and goals, the method for obtaining this relationship is not yet established. All five decisions are closely interrelated. Depending on the marketing ideology, each decision is given a certain weight. For example, when the marketing ideology is customer-oriented, the most important of these five decisions is the choice of customers.

The product can be tailored through its physical characteristics as well as through its service offerings which fit the requirements of the customer. According to Webster[30], the product and customer decisions a company makes are influenced most heavily by the company’s competitive advantage and market area strategy. This suggests hierarchical differences between the strategy components mentioned above.

It is possible to show the meaning of Ansoff’s concepts like market penetration, market development, and product development, using the five strategic decisions mentioned above and the concept of strategic position discussed earlier. The strategic decisions (1-5) define strategic position. If the company plans to move from one strategic position to another, it requires, for example, market penetration, new market development, or new product development which Shirley et al.[31] regard as marketing strategies. Strictly speaking, those concepts define the scope, direction, or nature of behavior carried out under a given strategy, but the content of that behavior must consist of functional factors. Various marketing functions are thus planned to carry out the chosen marketing strategies.

Even when company executives have not defined a specific and explicit strategy, it is possible to infer what the strategy is. Inferences can be made by examining the products, customers, and market areas of the company, as well as the marketing measures it is executing. How this concept of strategy as strategic decisions (product, customer, market area and core competencies) can be used in practice will be discussed broadly later in this chapter.

4.2 Corporate Strategy

As mentioned earlier, confusion has been created because strategic decisions on various hierarchical/ organizational levels of the company have not been well differentiated. We speak of strategies at three levels: corporate, business unit, and marketing (functional). This is somewhat complicated because the number of organizational levels varies within companies, mainly dependent upon the size of the firm. Large forest industry companies consist of four levels – corporate, division, business unit, and functional. Small companies often consist of only corporate (business) and functional levels.

4.2.1 The Idea and Process of Corporate Strategic Planning

Large forest industry companies typically consist of several business units or several groups of business units (e.g., divisions) operating as one financial entity. Business units can be from the same or different branches. Economic and financial questions are generally handled by corporate management, and strategic planning is particularly important at this level.

To increase manageability, the corporation is often divided into divisions. For example, International Paper has the following structure:

- Industrial Packaging

- Papers

- Cellulose Fibers

And, Canfor has:

- Solid Wood

- Pulp and Paper

- Energy

We describe corporate and division-level strategies together because the same principles can be applied in both cases. Instead of speaking of functional level strategy, we adopt a marketing-centric approach and speak only of marketing strategies. Later we will show how business strategies and marketing strategies are interrelated. As a result, we have two different situations for strategic planning: 1) planning corporate strategies and 2) planning marketing strategies. The most important reason for separating the two is that, especially in large companies, corporate and marketing strategies are planned and implemented on totally different organizational levels. Corporate strategy is the responsibility of top corporate management. Marketing strategies are planned and implemented on a business unit and product level. Of course, division of management responsibilities is closely related to company size. In small companies, the corporate strategy planning resembles business unit and marketing strategy planning. In this case, instead of using the term “corporate strategy,” it is more appropriate to speak of “company strategy” or “business strategy.”

Corporate strategy defines the scope of the firm with respect to the businesses, industries, and markets in which a company will compete. Overall, corporate strategy answers the question “Which industries should we be in?” and, therefore, competition is an essential element of corporate strategy. Corporate strategy should be planned so that resources are used most efficiently to convert distinctive competencies into competitive advantage.[32] To define strategy on various organizational levels, strategic decisions on each level must be defined. This follows our leading principle that the definition of the strategy concept must tell us what we do when making plans and decisions concerning strategies.

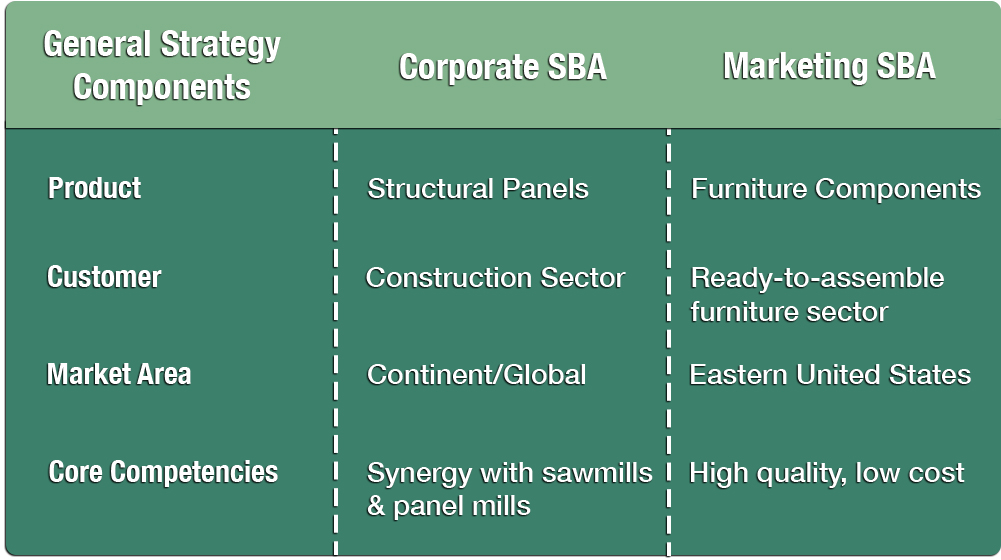

The following summarizes the definition of corporate strategy and the differences between corporate and marketing strategy. According to Ansoff, careful definition of the product/market area is an essential component of strategic planning. He suggests that strategic decisions are those which define the business area in which the company chooses to operate. These two comments can be used to distinguish corporate from marketing strategies. At the corporate level, product/market decisions are made with respect to the business area or industry chosen. At the business unit level, product/market decisions are clearly made with respect to products to be produced and customers to be served. When the business unit or marketing manager is considering what kind of products to offer, the corporate CEO considers which divisions, industries, businesses, or strategic business units to invest in or divest.

This idea is illustrated in Figure 4-4. At the corporate level, the product is defined as structural panels and the customer as the construction sector. These definitions become much more precise at the marketing level.

With this background in mind, we can list the basic phases of corporate strategic planning:

- Corporate mission definition (4.2.2)

- Strategic business unit (SBU) or strategic business area (SBA) definition (4.2.3)

- Evaluating the current business portfolio and making strategic conclusions/decisions (4.2.4)

4.2.2 Mission, Visions and Values

At the corporate level, strategy primarily consists of decisions regarding the businesses that the company should be in and what resources should be allocated to those businesses. These allocation decisions are guided by the company’s mission, vision, and values which provide overarching guidelines regarding the kind of organization the company wants to be and where it wants to go in the future. The concepts of mission, vision, and values are interrelated and their interaction should be the guiding light for the company’s strategy development.

Mission – In a basic sense, the company mission answers the question, “why does the company exist?” Only with a clear definition of the mission and purpose can a business begin to make clear and reasonable objectives. The mission is the foundation for all that follows. Answering the question “what is our business?” seems simple, but the answer is typically less obvious, and may include answering other questions like “who is our customer?” Often, various executives within a company will give very different answers to this question. This is one reason why it is so important—the process of developing the mission brings management together towards a common purpose.[33]

Companies within the forest industry often have very similar missions, but this actually violates one of the primary purposes of such mission statements. Companies should attempt to differentiate themselves from their competition. This differentiation is possible if each company considers its unique history, core competencies, and environment when developing its mission statement. Public relations should not be the primary purpose of a statement of mission. The mission should also be achievable, realistic, and motivating, so that it can provide guidance for both employees and managers.[34]

The mission should focus on markets rather than products, which means that it should concentrate on the broad class of needs that the company is seeking to satisfy (Example 4-3). General mission statements and the difference between a product orientation and marketing orientation can be shown as follows.

Paper mill

- We make paper (product orientation)

- We serve magazine printers (marketing orientation)

Sawmill

- We make sawn timber (product orientation)

- We make wood components for joinery companies (marketing orientation)

Manufacturer of prefabricated houses

- We make wooden houses (product orientation)

- We create comfortable living places (marketing orientation)

Example 4-3: Company Mission Statements

Based on an extensive review of the literature, Pietiläinen[35] developed a definition and breakdown of a mission statement. She suggests that a mission statement expresses the organization’s reason for existence and describes the nature of its business by answering the questions “what is our business?” and “what should it be?” Creating or updating a mission statement is an important part of corporate planning, as it motivates and inspires the members of the organization and guides resource allocation.

A mission statement can include the following issues:

- distinctive competencies

- purpose of the organization or philosophy

- business aims

- definitions of main stakeholders

- target customers and markets

- needs the organizations seeks to satisfy

- principal products and services

- geographical domain

- core technologies

A mission statement should be:

- inspirational

- short & easy to remember

- consistent with values

- clear and concise

- focused on markets rather than products

- distinctive from mission statements of competitors

- based on history, distinctive competencies, and the environment of the organization

- achievable, realistic, motivating, and focused on a limited number of goals

- same for all members of the organization[36]

Vision – When a company is founded, it is based on the vision of the owners. The vision statement helps maintain the original concept of the company and its future development. The vision is almost an “impossible dream,” yet it is simply a reality that has not yet come into being.[37] It provides a picture of what the future should look like, and guides the organization’s leaders toward that future.[38]

The vision statement must indicate a clear understanding of where a corporation is today and how it should proceed in the future. It should be seen as the primary corporate motivation, rather than profit.[39] Vision statements should be action-oriented, present- and future-based views of the dreams of executives. Unfortunately, these days vision statements are often no more than advertising slogans.[40]

An example of a forest industry company vision comes from ATS Timber in New Zealand: “To ensure all stakeholders needs are considered for generously with a culture of continuous improvement and profitability.” This shows the stakeholder focus of the company is balanced against the profit motive.

A vision statement is a mental image or an assumption of the desirable future state of an organization. It is a motivating tool in founding the company and maintaining the development and framework that guides decision-making. It enables differentiation from other organizations and forms a point of comparison against which achievements, culture, and behavior can be evaluated[41] (Example 4-4).

Example 4-4: Company Vision Statements

Pietiläinen looked at vision statements and developed perspectives on what a vision statement can and should include.

A vision can include the following issues:

- competitive position

- competitive advantages

- operating environment of the organization

- predicted economic trends

- changes in demand

- market focus

- position in the supply chain

A vision should be:

- realistic

- action-oriented

- concentrated on the future

- positive

- versatile (considering various stakeholders)

- interactive and dynamic

- believable

- attractive and clear

- harmonious with values

- stimulating

- creative

- practical

- concrete [42]

Value – a value is “a belief in action,” which means a decision is made about what is good or bad, important or unimportant. Every organization has values, realized or not, and values guide the operations of organizations. The values of an organization are usually based on those of top management. Values should be documented, consistent, practiced and honored; otherwise, the organization is in danger of managers following only their personal values.[43] Values can be said to reflect the sense of identity of an organization.[44] They should be clear, simple, direct and easy to understand.[45]

Values of an organization can be divided into three groups: ethical values, responsive values, and profit values.[46] Ethical values concern the environment, society and employees, while responsive values emphasize the benefit to customers. Profit values stress the economic point of view and the benefit to owners. Values might include providing opportunities for employee development, creating a safe working environment, or maintaining environmental friendliness.[47] Roseburg Forest Products operates using three basic values: 1) Sawdust in the Veins, 2) Handshake Integrity, and 3) Driven to Win.

Business values are statements that specify common rules and set boundaries for an organization by defining what is right and wrong and what is important. Business values reflect the organization’s sense of identity and define both internal and external behavior of the organization, making them vital to the organization’s culture[48] (Examples 4-5).

While the mission and vision may seem like grandiose statements with little meaning or practical use, how a company defines itself can have a dramatic impact on its success. These statements communicate the values and intentions to all stakeholders. Levitt[49] provides examples of how companies or industries have defined themselves too narrowly. For example, he discusses the challenges facing the railroad industry in the U.S. in the late 1950s.

The railroads did not stop growing because the need for passenger and freight transportation declined. That grew. The railroads are in trouble today not because the need was filled by others (cars, trucks, airplanes, and even telephones), but because it was not filled by the railroads themselves. They let others take customers away from them because they assumed themselves to be in the railroad business rather than the transportation business. The reason they defined their industry wrong was because they were railroad-oriented instead of transportation oriented; they were product-oriented instead of customer-oriented.[50]

In the mid-90s, Louisiana-Pacific Corporation went through a series of difficulties and changes in top management. The results of these changes brought about a significant shift in its corporate strategy. A decision was made to divest the paper side of the company’s business and to concentrate on being a building products company. Similarly, Scandinavian companies that once produced magazine paper now produce “solutions” for their publisher customers. While this may seem like an insignificant issue, the difference in culture between these two world-views can have a dramatic impact on firm performance.

Example 4-5: Company Value Statements

Pietiläinen[51] analyzed company values and identified what values might include and what companies should include in their values.

Values can include the following issues:

- ethical aspects: human rights, equality

- responsive aspects that emphasize the benefits to customers: service to others, humility, integrity, reli- ability, innovativeness

- relationship to owners: profitability, productivity

- relationship to employees: individual’s self-determination, social appreciation and acceptance, safety, employees’ development

- social responsibility: environmental friendliness Values should be:

- limited in number, not more than six statements

- known, consistent, practiced, honored

- purposely chosen & written down

- continuously discussed & checked regularly

- public

- lasting

- clear, simple, direct, and easy to understand

- attractive and capable of being respected

- suitable for different cultures

- effective – they should have a real influence on the organization

- consistent with each other

- feasible[52]

4.2.3 Strategic Business Unit (SBU) or Strategic Business Area (SBA) Definition

A business unit is the basic unit for which business and marketing strategies are created. The term “profit unit” is used if independent responsibility for returns or profits is emphasized. In smaller companies there may be only one business unit, in which case the terms “company” and “business unit” are often used synonymously.

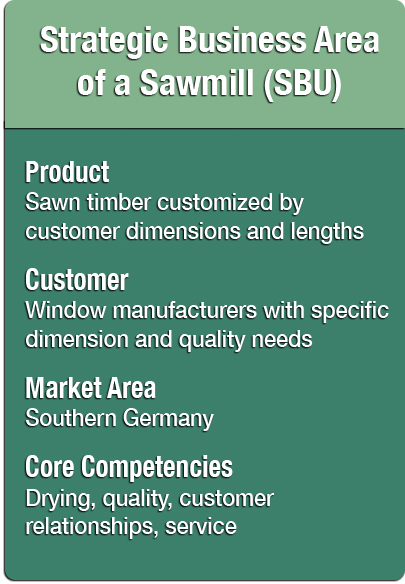

The terms SBU and SBA have been created for strategic planning purposes. A strategic business unit can be a single unit or collection of related businesses. The decisions in portfolio analysis are targeted to strategic business units. The SBA and SBU concepts are closely related. The strategic business unit is responsible for developing the strategic positioning on one or more SBAs. Abell[53] defines SBA in terms of three dimensions: (1) customer groups that will be served, (2) customer needs that will be met and (3) technology that will satisfy the needs. Ansoff[54] adds geographical location to the list.

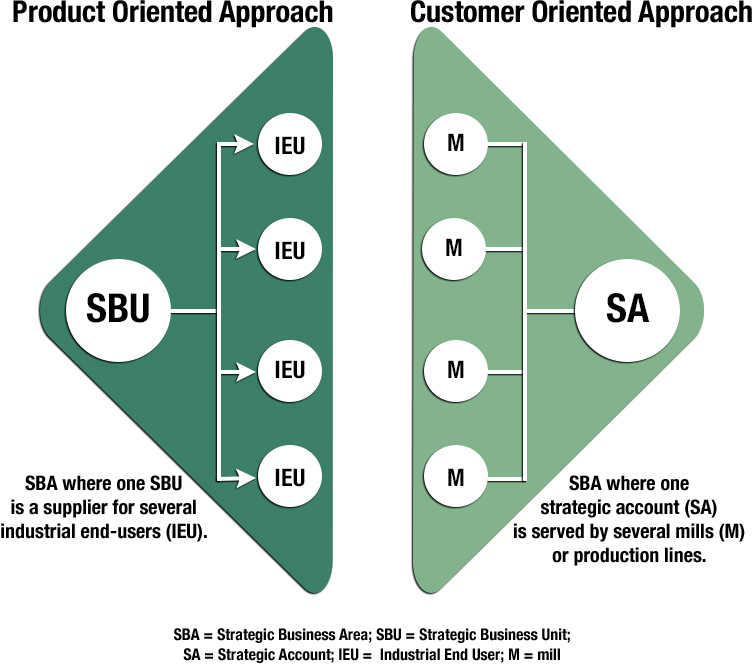

The difference between an SBU and an SBA can be explained through the company philosophy: production- versus market-orientation. In corporate strategic planning, a production-oriented company emphasizes SBUs while a market-oriented company emphasizes SBAs.

Example:

SBU – wood component mill or wood industry division

SBA – wooden furniture material business or wood construction material business

Figure 4-6 shows that when an SBU defines its marketing strategy it defines its SBA at the same time. The business of a corporation is composed of the SBAs of its SBUs or groups of SBUs.

Since the 1990s the general direction in the forest industries has been to concentrate on core businesses. Many multi-industry corporations have renewed their strategies and now concentrate only on forest-based industries. In the late 1980s, a Finnish multi-industry corporation Rauma-Repola started developing its corporate strategy by listing its strategic business units (also referred to as industry groups or business areas):

- Forest machinery

- Industry valves

- Rock crushing equipment

- Machinery for forest-based industries

- Grain harvesting equipment

- Offshore oil drilling products

- Printing papers

- Special papers

- Special pulps

- Sawn timber and value added

- Trading of wood products

- Plastic packaging and foils

By the year 2000, after a series of mergers, acquisitions, and divestitures, Rauma-Repola was part of UPM-Kymmene corporation which primarily consisted of the following three groups of business units called business areas:

UPM-Kymmene Printing Papers

Magazine papers, newsprint and fine papers.

Converting Materials

Label, packaging and envelope papers and converting units

Wood Products

Sawmilling and joinery, plywood, and building suppliers trade

A fourth group, called Resources, included operations such as chemical pulp, wood procurement and energy. Reflecting changing times in the market, today UPM refers to itself as “The Biofore Company” and its operations are organized around three areas:

Energy & Pulp

Energy, Biofuels, pulp, forest & timber

Paper

Publishers, printers, merchants, converters

Engineered Materials

Label stock & RFID, plywood, wood plastics

This structure is a result of corporate strategic planning, including the definition of SBUs and SBAs.

Strategic Accounts – Restructuring Corporate Strategy

Strategic accounts are normally connected to customer choices in strategic marketing planning. If a company’s customer choice is certain known end-users, these customers can be called strategic accounts or key customers. Strategic accounts are generally defined as those customers with the highest value to the company.

Strategic accounts are important at the corporate level of planning because of the size and power of the biggest customers. They might be global or multi-national companies using centralized and harmonized supply processes and preferring one-stop-shopping. Ongoing globalization and consolidation have increased the size of both forest industry companies and their major customers. Big paper users (printers and packagers) or big DIY chains can be larger than even the biggest paper or wood products producers. Very large customers are strategically valuable for the entire corporation and their needs should be taken into consideration in corporate planning.

Strategic account management is a method for dealing with very large customers. Because some mills or divisions may be too small to satisfy the multi-faceted demands of very large customers, the solution must be created at the corporate level. When a market-oriented corporation is making decisions concerning SBAs, the starting point could be a strategic account instead of a traditional end-use sector. In other words, a strategic account may mean that one key customer forms an SBA. Strategic account-based SBAs can actually impact the corporate organizational structure. This means that the whole corporate strategic planning must be market-oriented and more closely resembles strategic marketing planning.

Figure 4-7 depicts the difference between a traditional SBU-based SBA definition (left triangle) and a more modern SA-based SBA definition (right triangle).

In traditional production-oriented approaches, the SBU is the starting point and it serves several industrial end-users. SBU formation follows traditional production- or product-based borders. This kind of SBA definition means that one industrial end-user may belong to several SBAs of the supplying company. The customer may need to follow several business practices (of the various SBAs) even though it does business with only one supplier.

To simplify this situation for the customer (strategic account), the company can build the SBA around one (big) SA. Mills from various divisions serve the SA. The customer relationship is managed so that all the business procedures are harmonized and the concept of “one-stop” purchasing can be realized. In this way the company creates one “face” that is seen by the customer.

Strategic account-based corporate strategic planning limits the possibilities of marketing planning and coordination on lower company levels. Division level management must take accounts identified by corporate management into consideration in their marketing and production plans. Division level management may identify their own strategic accounts. At the mill or product level, planning the decisions of corporate and division managers must be taken into consideration before separate customer decisions can be made. Again at this level, managers may have their own strategic accounts.

Strategic account-based corporate strategy requires that the company and the customer share information and align many of their processes. Mutual trust and cooperation are needed to form a working, rewarding, and long-term partnership. The structures and functions of the company are planned so that they effectively implement the strategic account-based strategy.

4.2.4 Evaluation of the Current Business Portfolio and Making Strategic Conclusions/Decisions

Portfolio planning is the process of evaluating the current portfolio of business units. The results of the portfolio analysis give corporate managers the necessary information to appropriately allocate resources among the business units in the portfolio (Example 4-6). Two major portfolio tools discussed below are the Boston Consulting Group (BCG) Matrix and the General Electric (GE) Business Screen.

Example 4-6: Portfolio Planning

AssiDomän was once one of the largest forest industry companies in Sweden (total sales of over $2.5 billion in 1999) and one of the largest private forestland owners in the world. In 1999 the company underwent a major change in management that brought with it a process of restructuring.

The new CEO at the time stated that “My key task and that of Group management has been to increase the tempo of the work of improving efficiency and profitability after the rapid expansion of recent years. It has also been important to strengthen the work of defining the future structure and strategy of the Group and

its units in order to find a clear direction and focus for our business.” He went on to say, “We must make strategic choices. We must focus and invest in operations and businesses where we have the opportunity to assume a leading position. In the long term it is not possible to build up and defend a leading position in too many areas without diluting resources. To survive in the long run, we must be truly competitive, both geographically and within selected product segments.”

With this mentality, the company undertook a process of analyzing itself and the marketplace in an effort to identify the right portfolio for the Group and the right strategies and actions for those units maintained in the portfolio. A study of the market size and growth, return, structure and trends in the industry, capital intensity, and financial history was conducted. At the business unit

level, relative market share was determined with respect to the three largest competitors, achieved customer value was measured, and competence and capital efficiency were evaluated. With this information, each business unit was placed in a portfolio matrix representing market attractiveness and strategic position.

Based on the assembled data and resulting analysis, the company chose to divest some of its business units. Plans were made to sell the cartonboard business unit. The company felt that the unit was not large enough to provide long-term satisfactory development. The industry was fairly concentrated, making it difficult for AssiDomän to grow in this area.

The company felt that the kraft products market was stagnating and suffered from overcapacity. Sack conversion operations were seeing downstream consolidation with more consolidation on the horizon. Two kraft mills were kept, but the other two mills, as well as the sack plants and barrier coating, were sold. Barrier coating was seen as too small to effectively develop.

These changes resulted in a company that had three major divisions: Industry, Timber, and Forestry. The Industry division contained corrugated and containerboard as well as the two kraft mills producing bleached paper and bleached market pulp. Timber primarily consisted of sawn timber where the company was the largest producer in Sweden. Forestry was made up of 2.4 million hectares of forest land owned by the company.

Assi Domän. 1999. Annual Report.

Boston Consulting Group Matrix

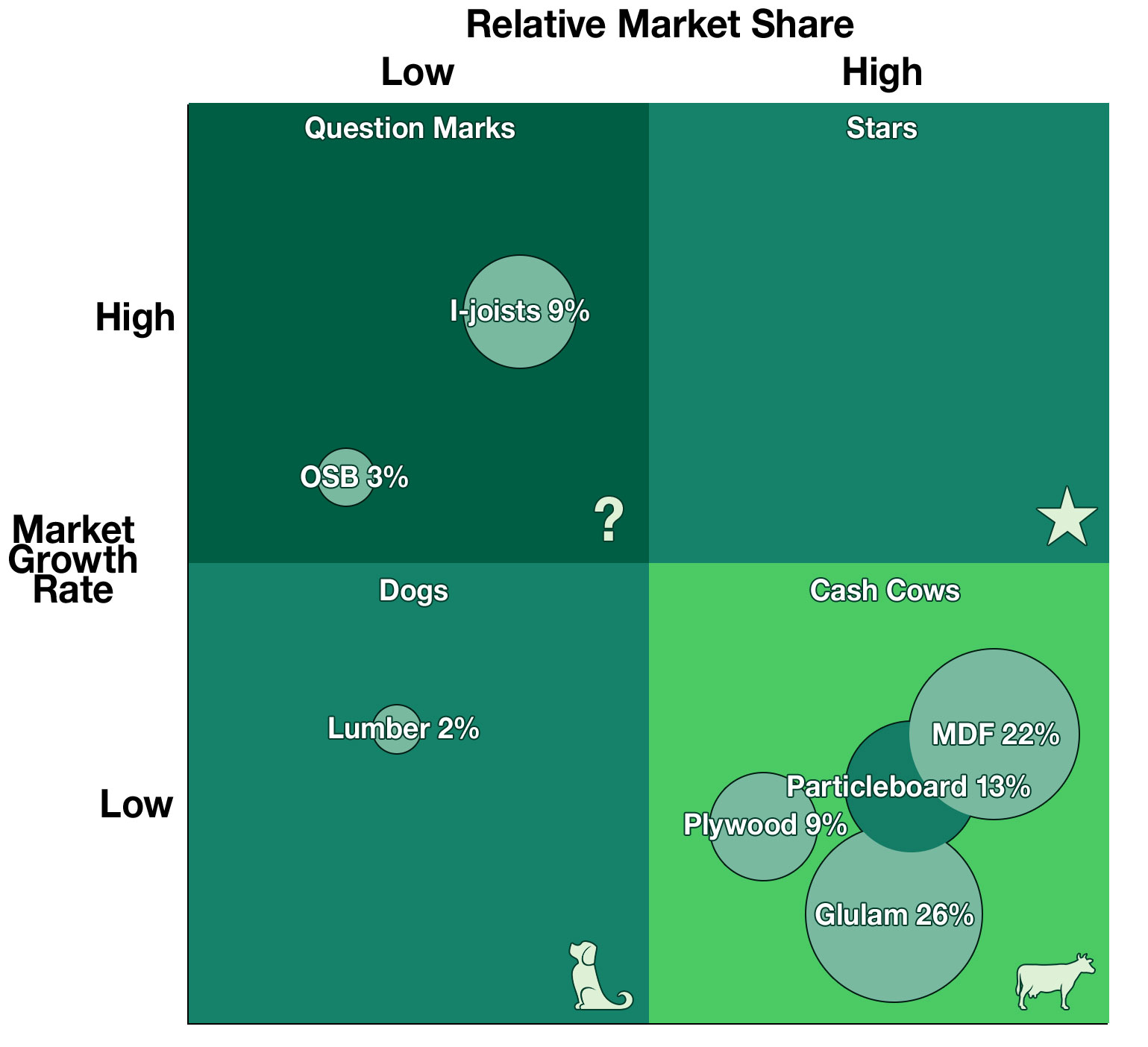

One of the most famous portfolio matrices is the Boston Consulting Group Growth-Share Matrix. The matrix is made up of four quadrants based on market growth (a general measure of market attractiveness) and market share (company position). As can be seen in Figure 4-8, the quadrants are typically named Cash Cow, Dog, Question Mark, and Star, representing the potential of business units or product in that category. A “Star” is a business unit or product that demonstrates high growth and in which the company has a high market share – an ideal situation for the company. On the other hand, a “Dog” business unit or product is in a low growth market and the company has a low market share, a considerably less ideal situation for the company

Size of bubble represents total market share for each product.

Also in Figure 4-8 is an example of how this matrix might be used to evaluate a company’s portfolio of business units. Lumber is low growth and the company in this example has a low percent market share, so it can be considered a “Dog.” Oriented strandboard and I-joists are both “Question Marks” since the company does not have a very large market share as compared to the competition and market growth is high. The company has several business units it considers “Cash Cows.” This should mean the company is in a position to invest in the “Question Marks” to move them towards becoming “Stars.”

General Electric Business Screen

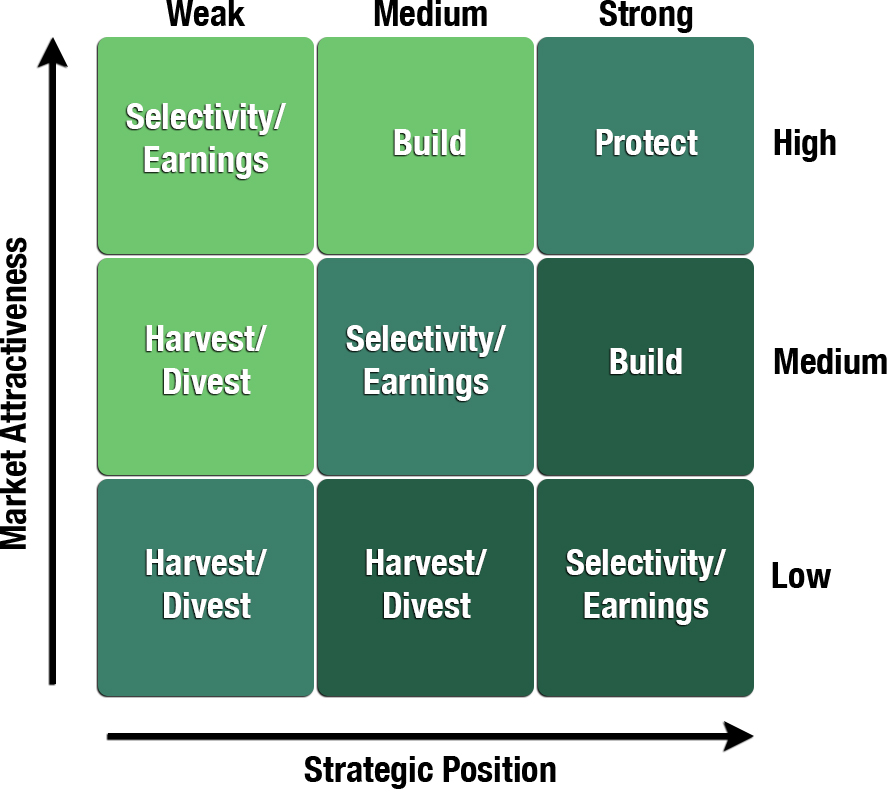

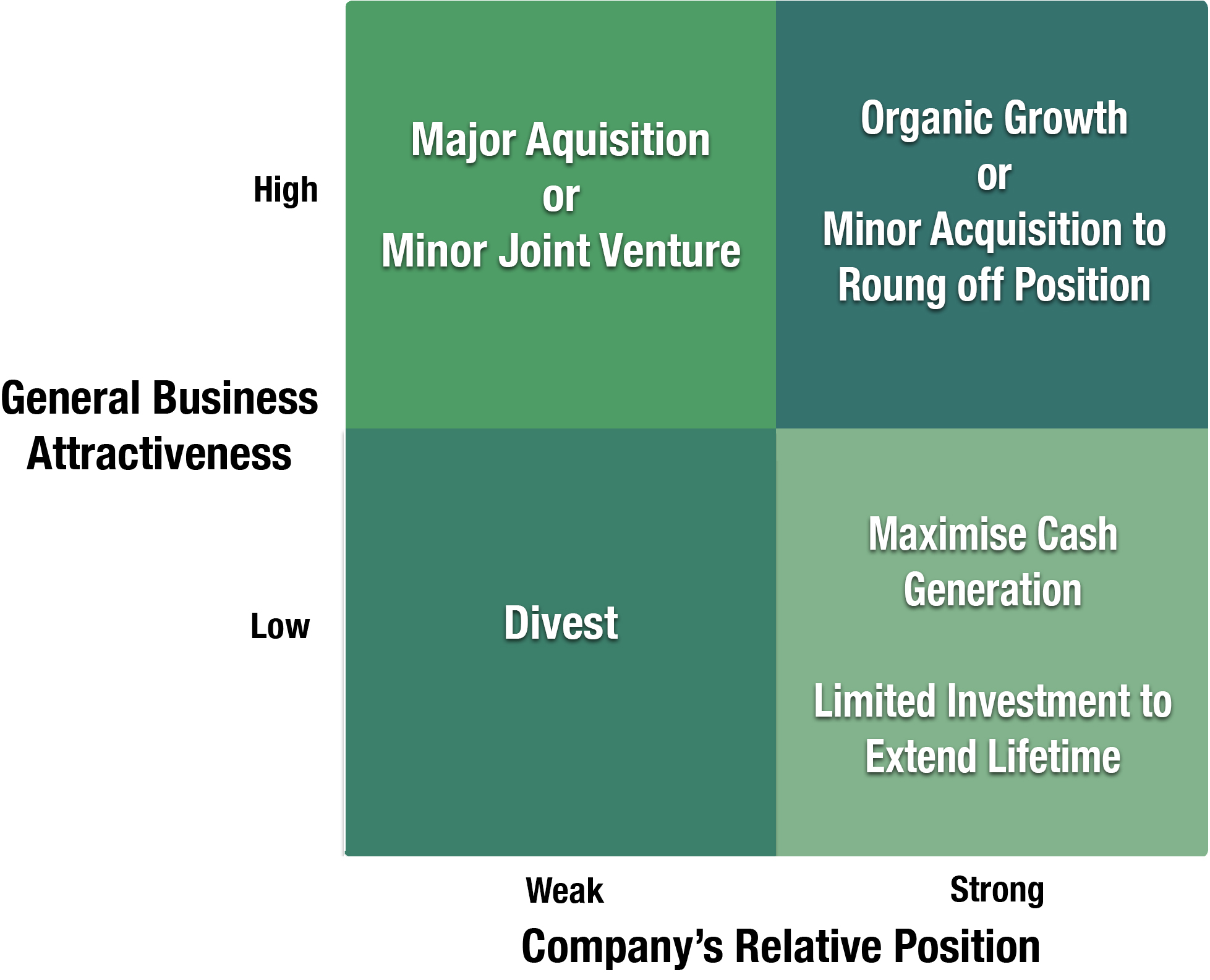

Instead of market growth and market share, the GE Business Screen uses market attractiveness versus SBU strength or position (Figure 4-9). The matrix can be divided into four or more cells depending on the level of detail deemed necessary. As shown in Figure 4-9, there are different recommendations for decisions regarding an SBU, depending on its position.

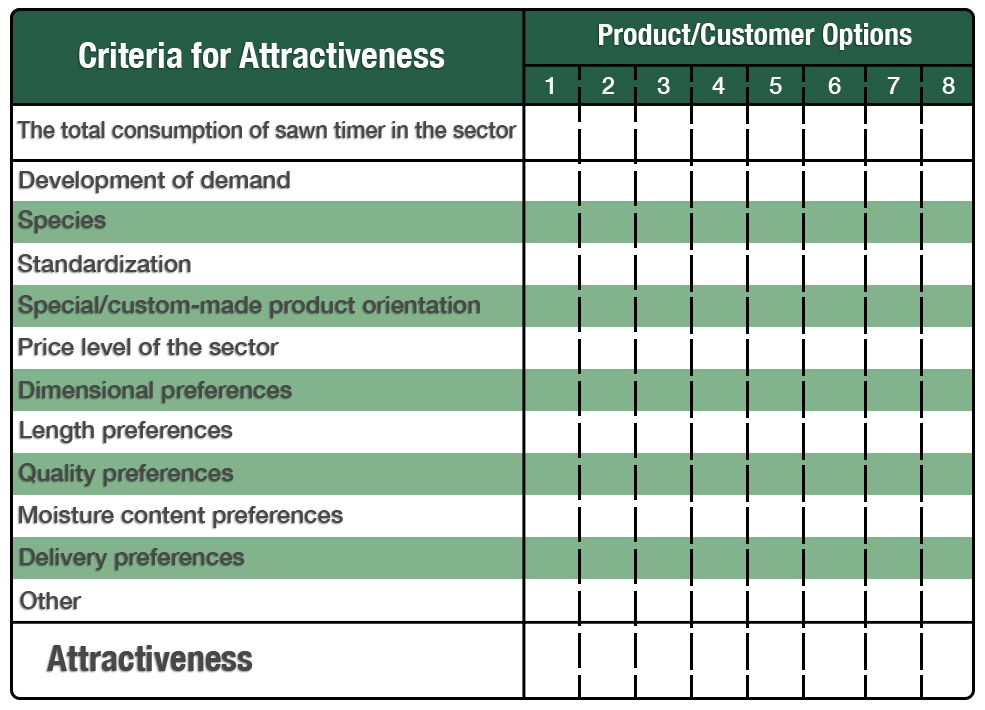

Placement of SBUs on the BCG Matrix or the GE Business Screen allows company planners to evaluate where to invest and divest. To learn how strategic choices are made, we follow a GE-type portfolio analysis in a specialty paper and converting division of a forest industry company. The top management of the division uses the following criteria to evaluate the general business attractiveness and company position.

Criteria for evaluating general business attractiveness:

- Market growth

- Market size

- Profitability

- Indispensability of the products

- Role of environmental issues

- Entrance threshold

- Degree of concentration of the competitors

- Geographical scope

- Negotiation power of the suppliers

- Degree of innovativeness

Criteria for evaluating relative position:

- Company’s market share

- Company’s technological level

- Quality of company’s R&D function

- Company’s cost structure

- Customer relationships

- Marketing know-how

- Organizational effectiveness

- Degree of integration

- Geographical location

- Effectiveness of distribution

- Profit

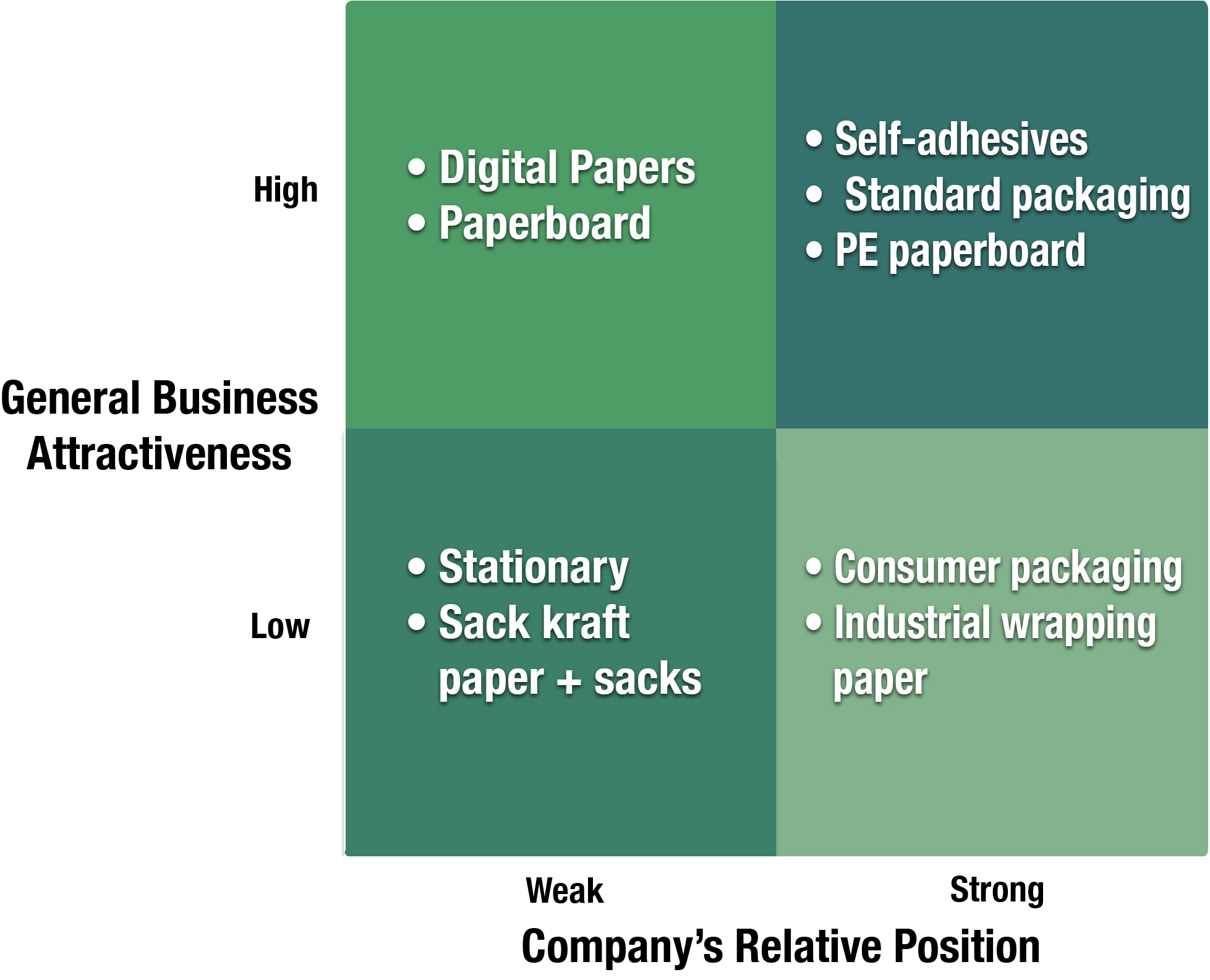

Using the above criteria, the current business units are located on the portfolio matrix and evaluated (Figure 4-10). The next step in the divisional strategic planning process is strategic conclusions or choices (Figure 4-11). In this case the following recommendations are made:

Divest (low market attractiveness and weak strategic position) – For products/businesses that clearly are losers or that the company has found it cannot effectively manage, divestment is the logical choice. This means selling the business unit. The company cannot make money with these products/businesses, and it is likely that the situation will not change in the future. These businesses deserve to be divested so that the company can concentrate on its core businesses. In this example the company chooses to divest the following SBUs:

- Stationary

- Sack kraft (paper + sacks)

Maximize cash generation, limited investment to extend lifetime (low market attractiveness and strong strategic position) – The basic idea with this option is to milk the SBU for resources that can be invested elsewhere. The company decides that in the long term, this product/business does not show promise and therefore deserves little or no investment. However, there is enough market for the product/business that it makes sense to continue to produce it, gaining whatever volume of sales will naturally occur. This option creates the risk that customers who rely on that product/business will not be happy to learn that the company plans to eliminate it. In our example the company chooses this approach for the following SBUs:

- Industrial wrapping paper

- Consumer packaging

Organic growth, minor acquisition to round off position (high market attractiveness and strong strategic position) – This option means maintaining the current position of the product/business. In our example, the following SBUs were seen to be in a maintenance or hold position.

- PE paperboard

- Self adhesives

- Standard packaging

Major acquisition or minority joint venture (high market attractiveness and weak strategic position) – For SBUs representing attractive markets but relatively weak position, the best decision may be to build a better position; that is, to increase market share and further improve the competitive position in that marketplace. In our example, the following two SBUs are considered to represent opportunities for building a better position.

- Paperboard

- Digital papers

The forest industry recently underwent extensive consolidation and companies are carefully considering how consolidation will progress. If a company has a weak position in a sector where a large competitor is aggressively acquiring capacity, they have an additional reason to exit the business area. For those product areas in a strong position but where business attractiveness is weak, it is best to simply maintain the status quo and use the cash produced by these businesses to invest in others. For attractive business areas in which the company has a strong position, it should plan to maintain growth and watch for opportunities to add to the businesses to make a more complete package. In our example, digital papers and paperboard are attractive business areas in which the company has a weak position. In this case the company should look to jump-start its operations and production. This way the company aggressively builds markets for products that will be strong in the future.

It must be remembered that matrices such as these are only a generalization of reality, and the recommendations cannot always be implemented. For example, many companies would consider softwood lumber to have low attractiveness and since it is such a fragmented sector, few companies can claim to have a strong position. In this situation, placement on the matrix would suggest that the unit be divested. However, there are many reasons why a company may not want to exit the production of softwood lumber. Sawmills typically serve as an outlet for higher-grade logs purchased by the company and as a source of chips and other by-products for paper production. Limited resources may mean the company can only implement some of the recommendations. In the example in Figure 4-10, the company may not be able to deal effectively with building its paperboard and digital paper operations simultaneously. It may have to prioritize one or the other.

4.3 Business and Marketing Strategy

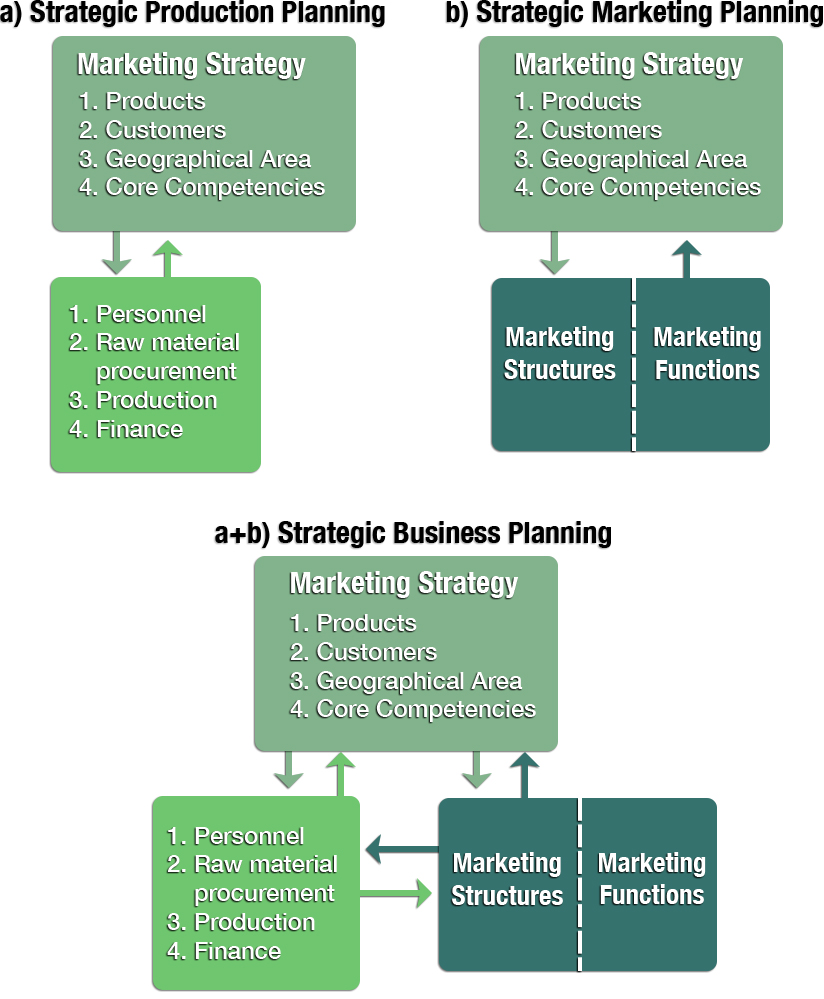

Business and marketing strategy are closely related. Business planning consists of two parts, marketing planning and production planning.

Marketing Planning:

- Strategies

- Structures

- Functions

Production Planning:

- Strategies

- Raw material procurement

- Production

- Finance

- Personnel

Because marketing is the link between a company and its customers and the company lives only through its customers, marketing planning dominates business planning. This means that in market oriented business planning, marketing strategies are directing the whole business planning process. Because of the dominating role of strategies, we can call it strategic business planning. In Figure 4-12 it can be seen how strategic business planning is composed of strategic marketing planning and (strategic) production planning. The same marketing strategies are directing both. In business planning of market oriented companies, marketing strategies are planned first and they are always a top management issue.

It is important to note that because the basic issues are very similar regardless of the hierarchical level of strategies, portfolio analysis is also applicable at the business and marketing strategy levels. Rather than evaluating an SBU, the tools are used to evaluate the situation with a specific product or product line.

4.3.1 Porter’s Generic Competitive Strategies

One way to define the basic approach to business strategy is using Porter’s[55] three generic strategies:

- Cost Leadership – a company pursuing this strategy will concentrate on reducing costs wherever possible and will practice tight cost controls. Typically, the company must also have highly efficient facilities and strong pursuit of experience-based cost reductions. Little would be spent on research and development, service, or advertising.

- Differentiation – a company pursuing this strategy strives to create a product that is perceived across the industry as being unique. Pursuing this strategy does not mean ignoring costs, but cost reduction is not the primary goal.

- Focus – with a focus strategy, a company concentrates on a specific buyer group or geographical market. The first two strategies aim towards industry-wide advantage, while focus is concentrating on a specific segment or niche. In this way, a company pursuing a focus strategy is able to essentially develop a low cost or differentiation strategy specific to its target segment.

A company that isn’t clearly pursuing one of these strategies is seen to be “stuck in the middle” and finds itself in a poor strategic situation. Implementing one of the generic strategies requires total commitment and appropriate organizational structures that become diluted if multiple targets are pursued. A number of researchers have looked at the forest industry from the perspective of these generic strategies (Example 4-7). A common finding is that many companies appear to be “stuck in the middle.” More recent research suggests that the Porter view of strategy may not adequately describe the strategic actions taken by forest industry companies.

Example 4-7: Strategy Research in the Forest Industries

A number of researchers have investigated the generic business-level strategies used in the forest industry. Results suggest that companies are moving away from an Overall Cost Leadership strategy to a Differentiation strategy. However, some of the research suggests that firms lack a coherent approach to strategy. This led to Swedish researchers questioning the use Porter’s generic business-level strategies in forest sector research. Their findings are shown at the end of this example and provide a contrast to some of the historical work.

Rich (1986)[56] looked at 36 of the top 50 forest industry companies in the U.S. during the 1976-79 period and in 1984. He found that there had been a significant shift away from Overall Cost Leadership as a strategy. In the period 1976-79, 50% of the companies were pursuing an Overall Cost Leadership strategy, 19% Differentiation, and 19% Focus with the remaining being mixed or no strategy. In 1984 he found many more mixed strategies (28%) with some more focus on differentiation and a clear move away from overall cost leadership (31%).

Bush (1989)[57]concentrated on the top 100 hardwood lumber producers in the U.S. Using cluster analysis, he divided respondents into five major groups. All the groups exhibited some characteristics of each generic business-level strategy. In this respect, interpretation of the orientation of each group was somewhat difficult. Generally, it can be said that two of the groups (the smallest firms) had no strong orientation along any of the generic business-level strategies. In other words, they were what Porter calls “stuck in the middle.” One group was oriented towards Differentiation and Overall Cost Leadership while the two remaining groups were oriented towards Overall Cost Leadership and Differentiation, respectively. None of the groups had a strong Focus strategy. Finally, the study found that companies intended to move in the direction of a Differentiation strategy in the future.

Niemelä (1993)[58] did his work in the softwood sawmilling sectors of Finland, British Columbia, Canada, and the western U.S. Managers at a total of 102 sawmills were interviewed and asked to identify their own strategy. Depending on country, between 21 and 23% of respondents selected a mix of the generic strategies. Finnish sawmills were least Overall Cost Leadership oriented with only 11% of companies claiming this strategy. In the U.S., 29% of companies selected Overall Cost Leadership and in Canada 23%. Differentiation was selected by 32%, 38%, and 26% by Finnish, U.S. and Canadian companies, respectively. Finnish companies were the most Focus oriented with 35% of respondents while U.S. companies were least with 12%. Twenty-nine percent of Canadian companies selected a Focus strategy. Generally he found that companies concentrating on Overall Cost Leadership were large, integrated companies with multiple mills. Differentiation and Focus oriented companies were smaller and more export oriented.

Hugosson and McCluskey (2009)[59] focus on the Swedish sawmilling sector. In their view, the previous Porter-based strategy research was insufficient and that more than three generic strategies are needed to describe changes taking place in the industry. Their work relies heavily on concepts from Ansoff to describe three strategy transformations that took place in the Swedish industry between 1990 and 2005: 1) market channel, 2) product value adding, and 3) service value adding. The market channel transformation refers to disintermediation and a tendency to deal directly with end-users. Product value adding means companies became more active in meeting the precise product specifications demanded by end-users. Finally, service value adding is primarily associated with distribution logistics services. Based on their findings, the authors argue that sawmilling companies clearly have developed new strategic behaviors, just not those described by Porter.

Hansen, Nybakk, and Panwar (2015)[60] looked at the effectiveness of pure versus hybrid strategies across US wood and paper manufacturers. As in previous research, they identified a tendency of companies to focus on overall cost leadership. Of their overall sample of 438 firms, they found 72 companies pursuing a pure differentiation strategy, 82 a pure cost leader strategy, 96 a hybrid strategy, and 188 were “strategically irresolute” or rated themselves low on both strategies. A differentiation strategy was most positively associated with firm financial performance.

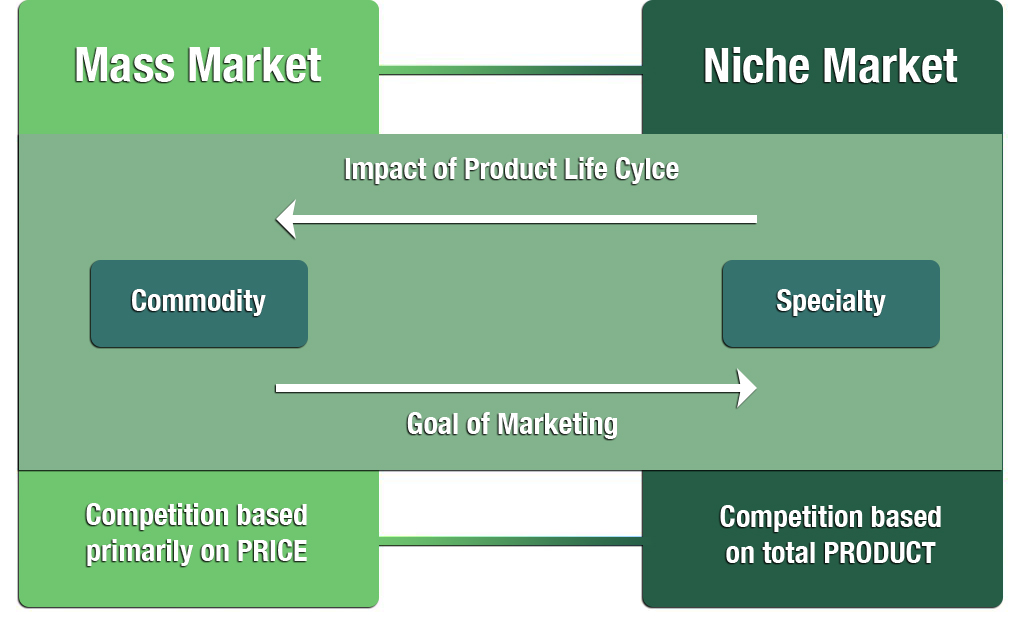

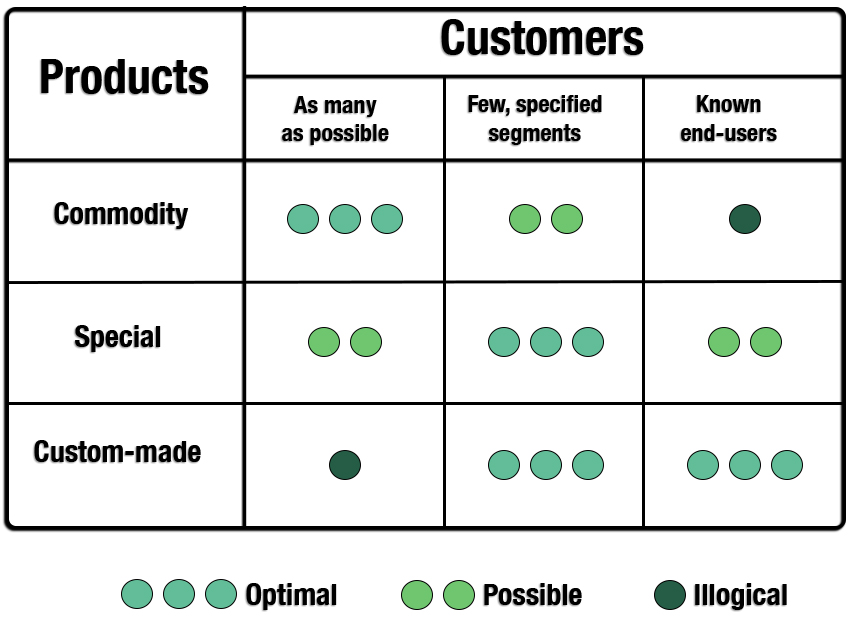

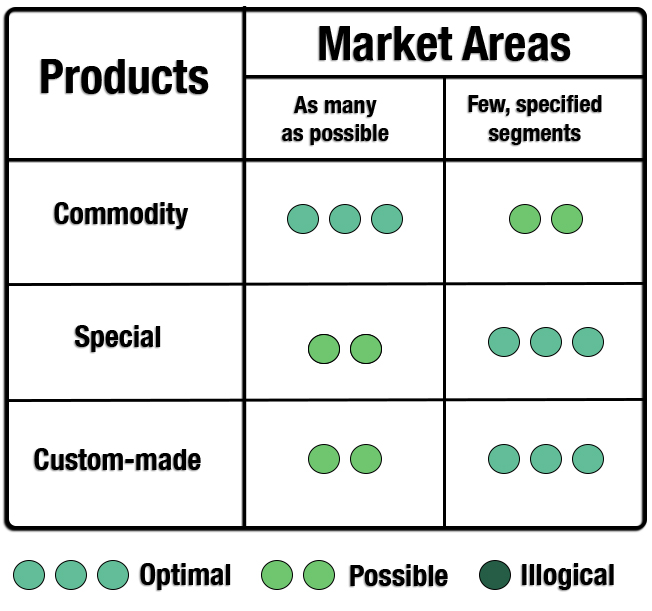

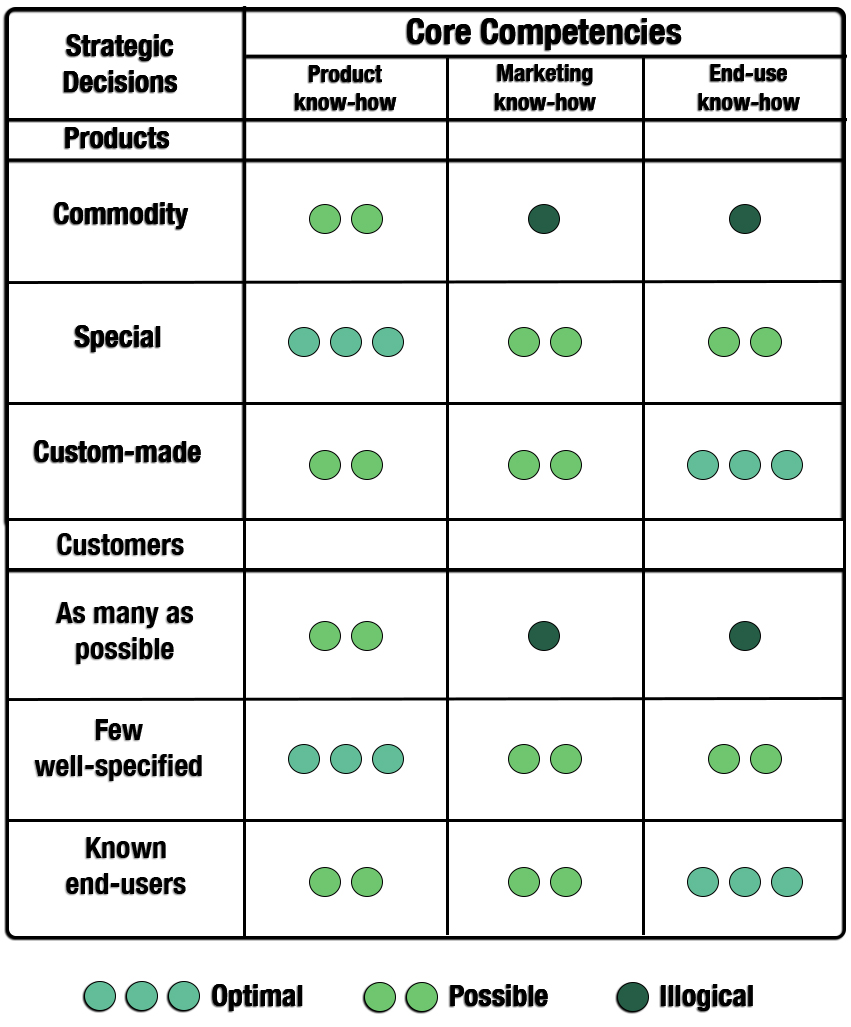

Clear connections can be found between Porter’s strategy concept and the modular strategy concept applied in this book (Table 1). Empirical studies suggest that in many cases it is difficult for companies to separate between few, well-specified customer segments and known end-users. The basic issue is if the company is selective or not in its strategic choices. This is also connected to a company’s marketing philosophy. A commodity product strategy is associated with a production-orientation and marketing decisions are rarely selective. Special and custom-made strategies are expressions of a market-orientation and marketing strategy decisions are selective. This is similar to Porter’s thinking. Cost leadership clearly emphasizes a production-orientation, and marketing issues are of minor importance. Differentiation and Focus strategies require marketing expertise and reflect a market orientation and selectivity in marketing decisions.

Table 4-1: Relationship between Porter’s Strategy Concept and the Modular Strategy Concept

| Modular Product Strategy | Porter’s Strategy Concept |

| Commodity Product Strategy | Cost Leadership |

| Commodity products As many customer groups as possible As many countries or regions as possible Cost and production-based competitive advantage |

|

| Special Product Strategy | Differentiation |

| Special products Few, well-specified customer segments Well-specified countries or regions Product and end-use based competitive advantage |

|

| Custom-made Product Strategy | Focus |

| Custom-made products Known end-users Well-specified countries and regions Customer relationship-based competitive advantages |

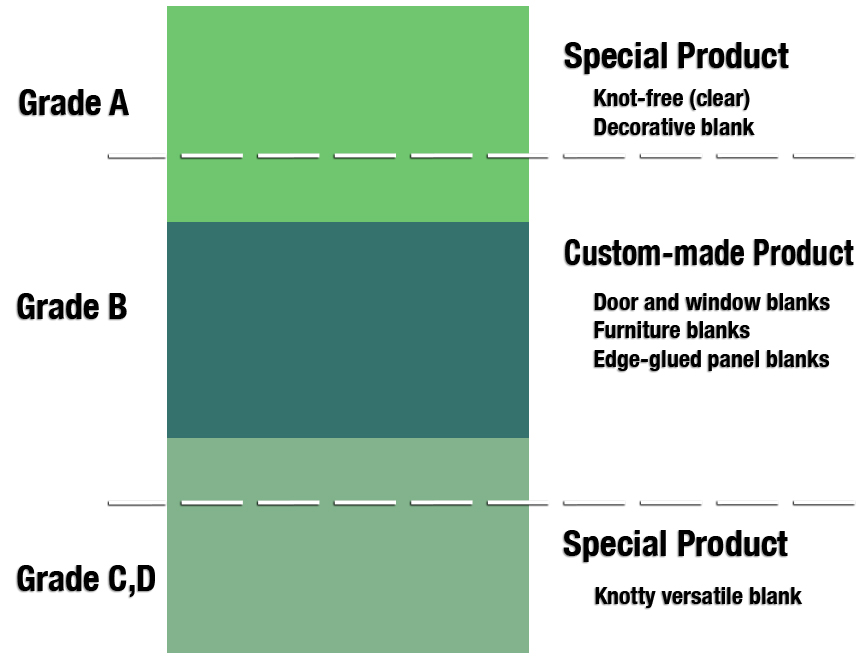

4.4 Strategic Product Decisions – Products to Produce

One of the most basic decisions facing a company is what product to produce. If a company decides that it will produce hardwood lumber, for example, there are still a huge number of decisions that must be made before it can determine exactly what the product will be and which services to offer.

4.4.1 The Concept of Product

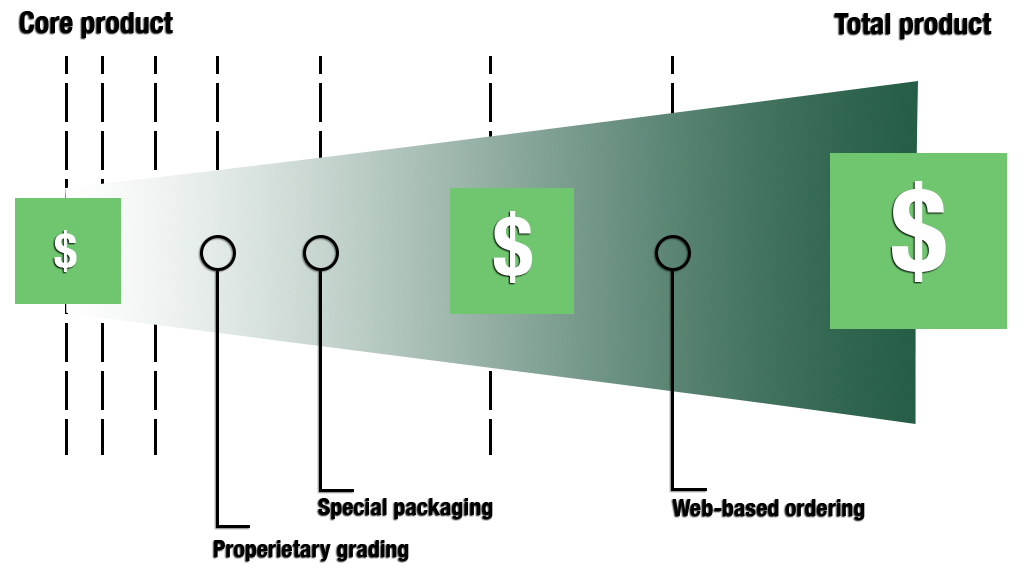

The Total Product

Early in the evolution of marketing, the term “product” simply referred to the physical object a company manufactured. In today’s highly competitive environment, companies must have more than just a good physical product. They must also provide an array of services associated with it that combine to form what has become known as the total product.

To understand strategic product decisions (product differentiation) we can think of products ranging from the core product to the total product (Figure 4-13). This is similar in concept to the levels of product proposed by Levitt.[61] The following list corresponds to Levitt’s categories and is based on Kalafatis et al.[62]

- Core product (the basic product, such as sawn wood)

- Generic product (softwood sawn wood to be used for manufacturing moulding)

- Expected product (minimum purchase condition, sawn wood of certain dimensions and species, packaged and delivered to meet specifications)

- Augmented product (an enhanced product based on the addition of special services such as credit or special delivery).

- Potential Product (everything that one might do to add value to the product)

The concept in Figure 4-13 is a way of looking at the product emphasizing that it is not only the physical piece resulting from the production process. In other words, we can consider a product to be a bundle of benefits satisfying customer needs. At the most basic level, the core product is the unimproved physical product. Through additions of either physical improvements or services and information, the product can move toward being a total product. The total product concept implies that a product is not ready until it is at the disposal of the customer accompanied by necessary information and service.

Traditionally, quality has been considered a critical element of the total product concept and an important differentiator among producers. However, it has been suggested that in today’s global business environment, where total quality management is virtually a given, product quality is also a given. This view suggests that product quality can no longer be used to differentiate among producers and ceases to be a source of competitive advantage. According to this notion, high product quality is simply a license to operate in the marketplace and provides no benefit to the producer.

While it is true that quality expectations are high in the modern marketplace, quality across the various aspects of a total product still present opportunities for competitive advantage. Achieving competitive advantage through quality requires an understanding of customer quality requirements, a method for measuring how well the company meets those requirements, and a strong commitment to do both.

Forest industry companies seldom systematically measure customer perceptions of product and service quality. Those that go the extra mile can put themselves in a position, through high product and service quality, to differentiate their product from the competition. In other words, a minimum standard may get you in the market, but superior quality is the only means of achieving competitive advantage.

The product concept above emphasizes the idea that product planning should be a shared responsibility between production and marketing. Naturally, customer needs and preferences and company capabilities are the most important starting points in product planning.

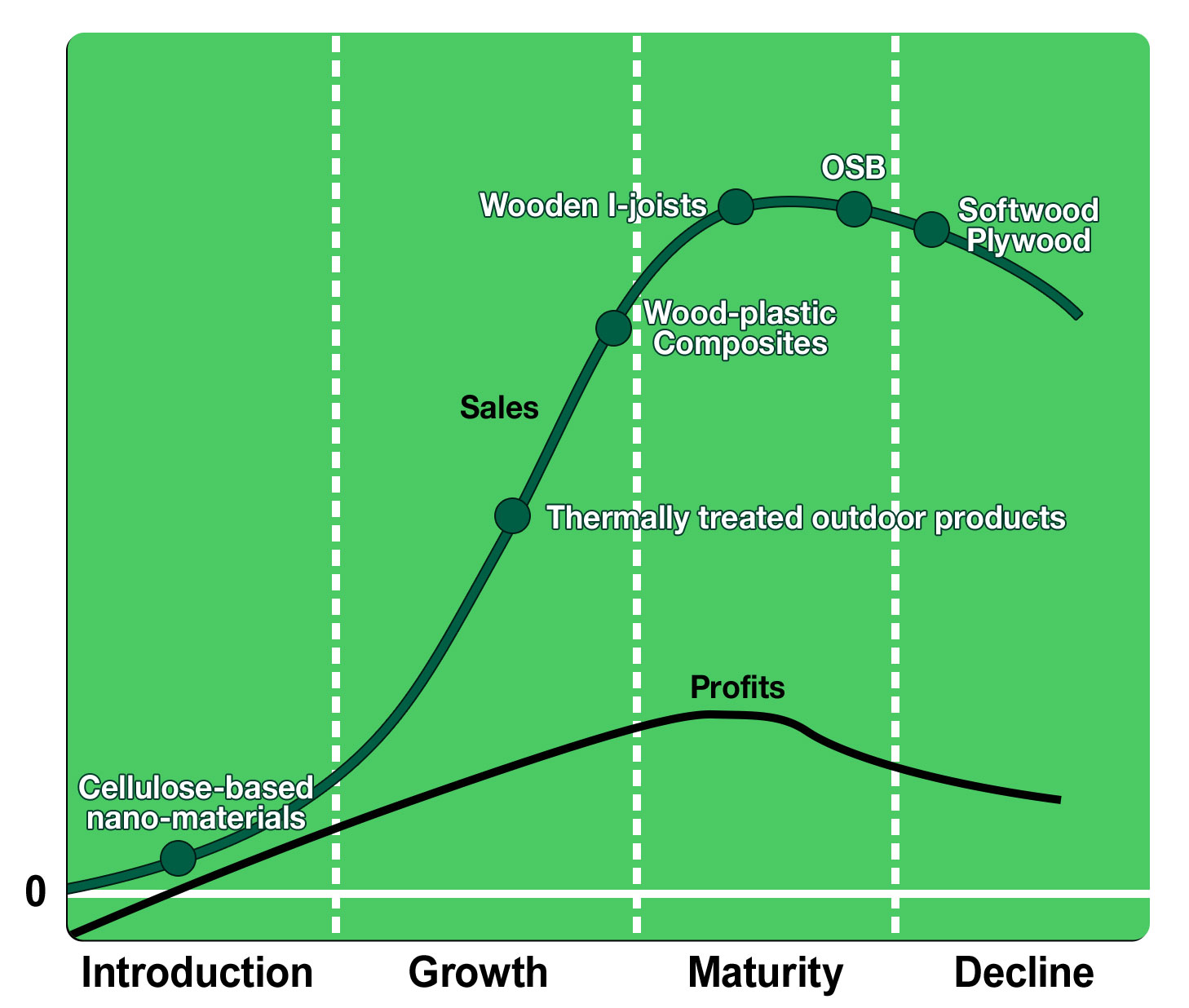

The Product Life Cycle

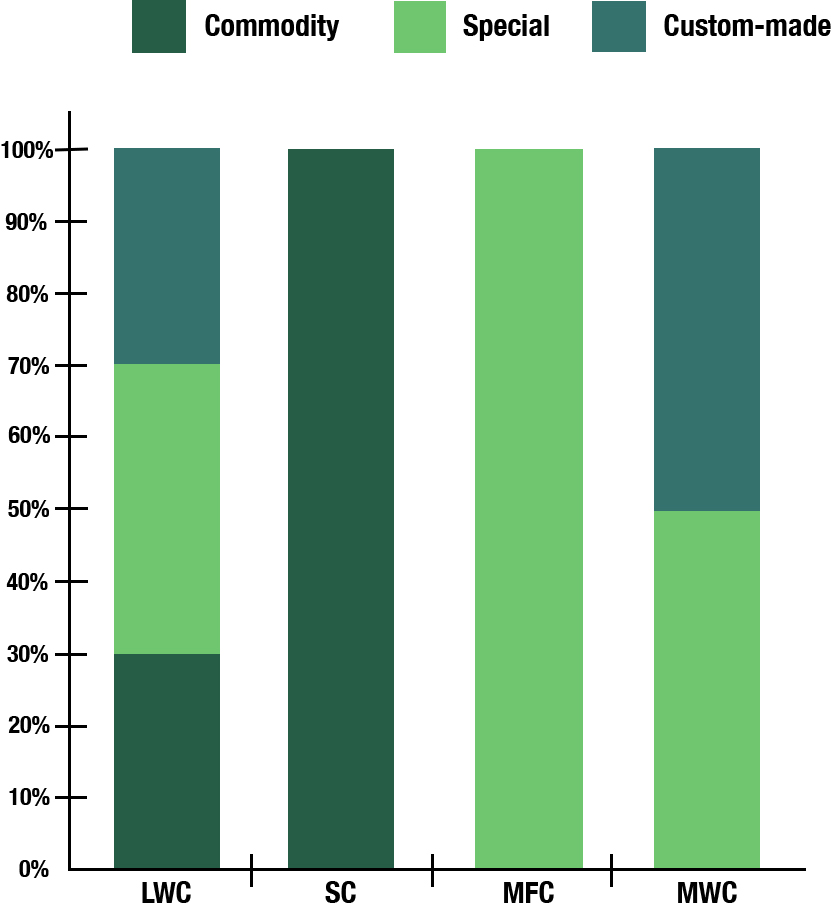

The product life cycle phenomenon is important from both a market attractiveness perspective and from a company-strengths perspective. Products progress through a life cycle similar to biological organisms. A typical product life cycle would follow the pattern shown in Figure 4-14. At introduction, the profitability of a product is negative due to investment to bring the product to market. As growth in demand increases, early investments are covered and the product becomes profitable. During maturity, the product should be profitable enough to contribute to the development of new products. A company should have a balanced set of products with respect to their relative stages in the life cycle. If a company is loaded with mature products and none in the introduction or growth stage, it is not well positioned.

At each stage of the life cycle, certain competitive conditions can be expected. At Introduction, there are few or no competitors. As the market growth of the product begins, it attracts competitors into the marketplace and the fight for market share begins. By the time the product reaches maturity and growth slows or stops, companies fight to maintain their market share and will tend to emphasize efficiencies and maintaining low cost. During decline, some competitors will leave the marketplace and the remaining ones will be selective in where they attempt to sell the product.[63] One incentive for maintaining a product during the decline stage is the exit of competition and the potential to develop a small but dedicated market.

An example from the North American industry can illustrate where various products fit along the product lifecycle. Nanoscience is in its infancy but some products have been commercialized such as cellulose nano-crystals used as an additive to the paper-making process. These products are at the early introduction stage of the product life cycle. Thermally treated outdoor products and wood plastic composites are in the growth stage. Wood I-joists are nearing maturity in the US marketplace while OSB has fully entered maturity. Softwood plywood is generally in the decline stage of the life cycle.