Week 4: Reading

Orthopteroid Orders

The Orthopteroid Orders is a general grouping of the more primitive neoptera groups that share characteristics similar to the order containing the grasshoppers, crickets and katydids, the Orthoptera. These orders are paurometabolous, meaning they complete development in successional stages with no pupal stage; sexual development and adult tissue development advances with each molting event until the insect has reached full maturity (for winged members, the wings are fully developed). All members of this group have chewing mouthparts, and many species have massive mandibles and maxilla. All members of this group are phytophygous except the Dermaptera (earwigs).

Usually for the Orthopteroids, eggs are laid in clutches, grouped together and held with some kind of material from the mother ranging from a wet, slightly viscous mucous to a toughed, styrofoam-like case. However, there are members of the Orthopteroids that do not do this – for example, stick insects (Order Phasmatodea) lay eggs one at a time, dropping them to the ground as they are produced (figure 4-1).

The Orthopteroid Orders

The Orthopteroid Orders include the extant orders of the Paleoptera, and the Blattodea/Isoptera Orders examined in Week 2 reading.

The Orthoptera are considered “primitive” because of the paurometabolous life cycle and the simplified body plan. They are relatively large insects in general, with two pairs of wings when present (several species have secondarily lost wing structures). The forewing is thicker in texture, parchment-like, and is referred to as the “tegmina”. This is a common term in other orders with similarly thickened wings. The wings may also be modified to create sound, and the calls of the Orthoptera will be specific to species and reason for the call: defense, mating calls, territorial calls, etc. In addition to the wings and sound production, the true Orthoptera can also be identified by the enlarged hind femora, modified for jumping (a saltatorial leg structure; figure 4-2).

Orthoptera are most often noticed in crop and production systems because of the rapid amount of destruction caused with large, chewing mouthparts. Within the order, however, there are only a few families that will become problem pests (like the Short-horned Grasshoppers in the family Acrididae), mostly because they will be multi-generational in the same season. Adult females will use the large, obvious ovipositors (figure 4-3) to dig holes at the base of host plants, depositing eggs into the hole where the newly-hatched offspring will have ready access to food.

Stoneflies, order Plecoptera, are also considered Orthopteroid, but have little importance to production systems. Though they are important contributors to aquatic and riverine trophic systems, they do not feed on crops or cause damage. Occasionally they will feed on pollen to gain sufficient protein for mating, but they do not feed with high enough intensity to be considered pollinators.

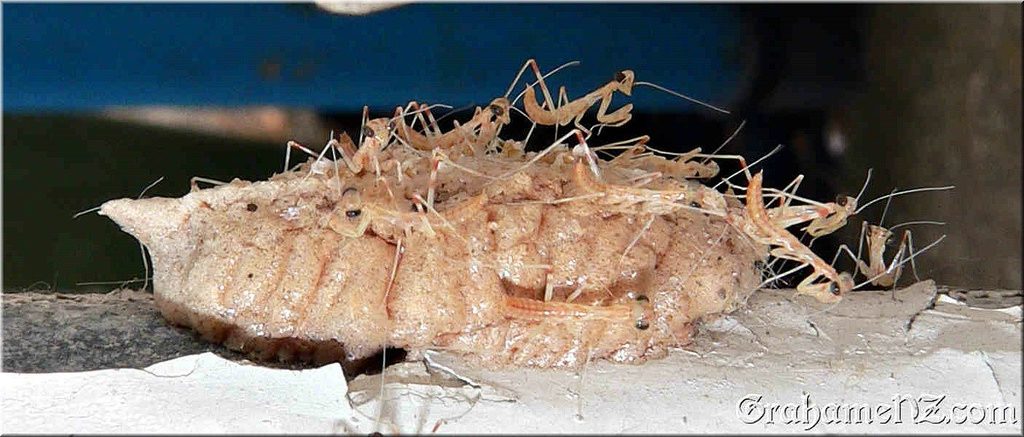

The Phasmatodea includes the walking sticks and leaf bugs. There is one species of stick bug, the Northern Stick Bug, that has been reported in Oregon but sightings are extremely rare (figure 4-4). Other species of this Order have been restricted for transport as pets or for husbandry in the last few years due to their ability to feed heavily on members of the Roseaceae family, particularly within the genus Rubus. These insects are a potential invasive pest due, especially since many of the females are parthenogenic, producing viable eggs without male fertilization, allowing colonies to grow rapidly.

The order Dermaptera is more commonly referred to as the “Earwig” order, and there is only one family in Oregon: Forficulidae, the family for the invasive European Earwig. The tegmina of the earwig is extremely short, covering only a few of the most anterior abdominal segments leaving the rest exposed dorsally. The hindwings are surprisingly large, and are folded fan-like beneath the tegmina when not in use. Another readily assessed characteristic of this group are the large, forcep-like terminal appendages. Males will use these to fight and remove other, competing males when there is a female present. The shape of these appendages make it easy to distinguish male from female: a recurved inner margin indicates male, while a relatively straight inner margin indicates female (figure 4-5).

The Dermaptera are cosmetic pests: not only can they be startling, but they may defecate on the surface of fruit and flowers of ornamental plants. However, these insects are not necessarily economically damaging, as this is the only Orthopteroid group that may predate on other pests present.