II. Learning and Success

Research as an Enterprise

Dr. Caroline C. Whitacre

Over the last two decades, the composition of Research Offices has dramatically changed along with the titles and expectations of research officers. What has caused this shift? And how can the contemporary Chief Research Officer (CRO) be successful in this new more demanding environment? First, there must be an ecosystem of research literacy among the top leaders of the university. The president, provost, and CRO collectively need to recognize the role that research plays in the advancement of the university’s reputation. Research successes of the faculty must regularly be communicated to the public in understandable, non-technical language. This communication should be coordinated among the top leaders of the university and be a regular occurrence. Second, contemporary research must be seen as highly purpose-driven and directed toward societal need. Today’s research enterprise requires the addition of center/institute structures, whereby faculty of widely different disciplines are co-located and performing interdisciplinary work. Third, funds to support this interdisciplinary work tend to rely on a diversity of funding sources, including federal grants, state and local grants, foundation grants, university-industry partnerships, entrepreneurial return, and philanthropy. While funding for university research has grown from all sources in recent years, there is substantial opportunity to grow further in the area of industry partnerships. Fourth, making fundamental decisions about university research such as what strategic areas to invest in, what funding sources to pursue, what centers/institutes to establish, and so on, necessitates access to reliable data. Building the case for research investment requires an understanding and appreciation of local assets as well as a thorough knowledge of the institutional faculty, their expertise and existing relationships.

Higher education institutions have changed dramatically in the past twenty years, certainly during the pandemic, but starting long before that. In this essay, I focus on research and start by postulating about what has brought on that significant change. In my view, there have been three elements which together have catalyzed a complete re-thinking of how research operations are conducted. First, expectations have changed for research at universities. Researchers are expected to be problem solvers for thorny problems in the community, attentive mentors for undergraduates, graduate students, postdocs as well as junior faculty, spellbinding communicators of their research findings, compliant followers of increasing loads of federal and state regulations, stimulating classroom instructors, dutiful members of university committees, conscientious reporters filling out miles of paperwork required by both internal and external offices, as well as leaders in their fields of research inquiry. These duties represent an expansion of the job description beyond the traditional research, teaching, and service responsibilities of the past. Second, there is an increased focus on rankings among universities today. US News and World report rankings, the National Science Foundation (NSF) Higher Education Research and Development (HERD) survey, the Times Higher Education World University Rankings and Blue Ridge rankings for medical schools are just a few of the major high-profile ranking systems in use today that elicit intense scrutiny among higher education leadership, all in the name of bragging rights. Central to those ranking systems is research funding, often measured in terms of research expenditures. A notable exception is US News and World Report, whose ranking includes a sizable proportion based on reputation. I would argue that research plays an outsized role in scoring of reputation. How often do we see press releases from University Communications offices touting an increase in rankings for any of these sets of metrics? Offices of Institutional Research (sometimes renamed to have Competitiveness or Strategic in their titles) spend hundreds of hours combing through university data trying to figure out how to game the system and gather every last piece of data to boost their university’s position. Reporting even higher numbers than last year doesn’t guarantee a higher ranking, since everyone else is rising as well. Third, there has been a notable emphasis placed on measurement of outputs in research. Rather than focusing solely on research dollars as in the past, there is increased emphasis placed on what institutions DO with that money—publications resulting from research grants, patents arising from university inventions, licensing of university discoveries, and start-up companies spinning out from university entrepreneurial activity.

As a result of changes in expectations, rankings, and measurement of university research output, there have been some rather noticeable changes in the organization and composition of University Research Offices. There has been an expansion of responsibilities to include commercialization, corporate engagement, entrepreneurship, competitive intelligence, research development, proposal development, and research communications to name a few (Droegemeier et al. 2017). Alternatively, some universities have elected to form new entities to handle these responsibilities, which oftentimes compete with University Research Offices for resources and confuse faculty. The leadership titles of some research offices have also undergone a transformation—from Vice Provost or Director for Research in the past to Vice president for Research, Senior Vice President for Research, Executive Vice President for Research, Senior Research Officer, Vice Chancellor for Research, and so on, often reflective of the reporting lines of these positions. Words have been added on to those titles, words like Innovation, Economic Development, Creative Activity, and Knowledge Enterprise, for example. With the expansion of responsibility that has occurred over the past twenty years, how can contemporary research officers coming into these positions be best positioned for success? In this essay, I treat four topics that I feel are critical to a successful research enterprise today—research literacy and recognition of the importance of research among university leadership, fostering an environment of interdisciplinary research, attraction of research funding from diverse sources, and access to comprehensive and reliable data sources.

Research Literacy

In this context, with the term “research literacy,” I am referring to familiarity and ease of speaking about research topics. While the senior Research officer at a university and their top-level staff are quite familiar with research topics (built into the qualifications for their positions), this is not always the case for the president, provost, and other university leaders, especially those coming into the academy from the outside rather than rising up through the academic ranks. It is absolutely essential that university leadership understands the importance of research to the reputation of a university.

University presidents and provosts have a myriad of opportunities to speak at occasions ranging from football game brunches to national higher education meetings. Those remarks, no matter the occasion, are typically highly scripted by attentive communications staff members who gauge the impact of the speech and the response of the audience both immediately and emanating from social media. It cannot be overestimated how important those opportunities are to get the message out about the university. With that sort of megaphone, the president and provost have become the major spokespersons for university messaging along with website content and message releases.

So how can chief research officers work research messages into presidential remarks and provost speeches? Some presidents/provosts get it right away, particularly if their background is in a traditional research-intensive discipline. If not and especially if they come from outside academia, a regular communication from the CRO to the president/provost about research highlights is helpful for getting the message across. Creation of a succinct list of top ten research highlights happening that month would be useful in providing the president with suggestions for his or her communications. When the CRO sends that list to the president, the CRO should also send it to the president’s or provost’s speech writer and to the university communications office for maximum coverage. Having research more broadly discussed at the top university leadership level also builds trust among the faculty.

The idea of research literacy is about building a culture of research on campus and in as many communications about the university as possible. The saying that “any publicity is good publicity” is not true for research. Sometimes there are negative stories about research, namely, research misconduct findings or lab accidents or financial fraud in research, that make headlines. These tend to stick around longer than positive stories and keep getting resurfaced particularly where litigation is involved. The goal is to get as many positive stories out as possible. For example, one campus recently conducted a contest for “Coolest Science Story of 2022” and had the entire campus vote to select the winner. Although the prize was a mere trophy and $500, the enthusiasm that was generated among faculty and students and the anticipation built around the ultimate announcement was palpable. And that was just inside the institution where over 4,000 votes were cast. There was also interest in the community where the story was carried in the local newspaper. Another example of building a positive culture for research is holding recognition events for highly productive researchers. These can take the form of dinners or receptions for researchers who have received national honorific recognition for their research or for innovations such as patents, licenses, or starting a company. It is often the recognition by one’s peers and heralding of success that is almost as valuable to faculty as a monetary prize.

The Case for Interdisciplinary Approaches to Research

Over the last fifteen years, there have been several lists of large, expansive challenges published with the goal of laying out global problems in need of solving. Two prominent examples of these lists are the Engineering Grand Challenges, released in 2008 (National Academies 2008), and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, first released in 2012 (United Nations, n.d.). A more recent list was put out by the National Science Foundation in 2017 to highlight NSF’s 10 Big Ideas (Table 1). The Engineering Grand Challenges were arrived at by an international group of technological thinkers who were asked to look ahead to the largest problems facing humankind in the twenty-first century. The group organized the challenges into four cross-cutting themes of sustainability, health, security, and joy of living. Some of these challenges were quite focused, such as managing the nitrogen cycle or making solar energy economical, while others have seemed virtually unlimited and unattainable, such as restoring and improving urban infrastructure or preventing nuclear terror. The UN Sustainable Development Goals and the NSF Big Ideas are similarly broad in their reach—to end poverty, take urgent action to combat climate change, and harness the data revolution, for example. One commonality characterizes the items on all three lists—they are purpose-driven and directed toward societal needs. Moreover, the lists cover huge swaths of disciplines—from physical science to social science, agriculture, education, and medicine.

Table 1. NSF’s 10 Big Ideas

- Future of Work—Building the human-technology relationship

- Growing Convergence Research

- Harnessing the Data Revolution

- Mid-Scale Research Infrastructure

- Navigating the New Arctic

- NSF 2026—Seeding investments in bold foundational research questions

- NSF INCLUDES—Transforming education and career pathways

- Quantum Leap

- Understanding the Rules of Life

- Windows on the Universe—Nature of matter and energy

These lists of problems received national and international attention and sparked thinking at universities. The problems lists catalyzed faculty from diverse disciplines to start talking to each other and collaborating. Not that faculty weren’t talking to each other and collaborating before 2008, but these highly publicized lists of pressing needs and “big hairy audacious goals” brought a new urgency to faculty collaboration and a new source of support as funding agencies willingly embraced the global problems approach.

With the emergence of larger foci of research such as the list in Table 1, research approaches directed at those questions required collaborators from widely varying disciplines. There has been a large increase in the emergence of research institutes or centers on campuses, in part to coalesce the interests of those researchers around a central theme and often resulting in co-locating those researchers in common spaces.

One curious aspect about the lists of global problems (as exemplified in Table 1) was the complete absence of any mention of humanistic or artistic approaches to these problems. This was something universities had to wrestle with in the approach to their new centers and institutes directed at global problems. The arts and humanities have a lot to contribute! For example, the UN Sustainable Development Goal of “ensuring inclusive and equitable quality education and promoting lifelong learning opportunities for all” would be quite lacking without the inclusion of artistic and humanistic approaches. Moreover, the understanding of the goal of “reducing inequality within and among countries” would be incomplete without a historic and philosophic context. So universities set about designing new centers and institutes directed at global problems and with the goal of inclusion of all disciplines.

A prime example of a long-standing university institute that was “at the right place at the right time” to further the UN Sustainable Development Goal of “taking urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts” is the Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center at The Ohio State University. First started in 1960 as simply the Byrd Polar Research Center, the goals of the center have always been to promote interdisciplinary research and to highlight the climate changes in the polar and alpine regions of the world as well as the impacts of climate on the environment and society. These goals have been facilitated by an extensive library, archives of polar exploration, polar rock repository, and ice core collection, as well as a strong program of public outreach and communication. It is centers such as Byrd that train succeeding generations of climate scientists. Thus, this center is an excellent example of an already existing entity that was poised to undertake the daunting challenge of climate change.

What about a more recently developed initiative that grew out of the explosion of global challenges environment? Arizona State University’s Sustainability Initiative represents such an example, as a vision of the president, Dr. Michael Crow, and begun in 2004 with a $15 million gift. Today, almost twenty years later, the Initiative has more than 500 members and places special emphasis on urban environments, connecting scientists, scholars, humanists, engineers, policymakers, business leaders, students, and communities as partners to advance teaching, learning, discovery, and innovation. What is most notable about this initiative is that the science is translated into sustainable operations across all units of the four ASU campuses and beyond to the city of Phoenix. The Sustainable Development Goals are explicitly called out in the description of the Global Institute of Sustainability and Innovation.

Thus, the creation of centers and institutes are an outstanding mechanism for faculty to come together around an area of research focus. These centers have become increasingly interdisciplinary as the global problems they focus on are more all-encompassing and thorny. It is important that the new knowledge created in these centers/institutes get embedded into the learning environment, particularly into relevant courses and seminar series. Some of these centers/institutes have spawned new undergraduate and graduate degree programs, teaching students concepts and tools they need to solve real-world problems. Examples include the Master of Sustainability Solutions Degree and Master of Sustainability Leadership offered by the ASU Sustainability Initiative.

These institutes have also become the focus of philanthropic successes as big global problems often catch the attention of large donors, as was the case with the ASU Sustainability Initiative. Also, funding agencies have put expanded dollars toward global problems and awarded funds to some of these large centers. Thus, the funding models for these centers are somewhat more varied than traditional university research programs. In the creation of a center, often, a small pot of internal university dollars can be leveraged to attract federal, state, foundation, and philanthropic support. Offices of research can be quite helpful in creating these interdisciplinary centers by offering a pot of seed money and requiring the participation of multiple departments and colleges. A clear set of requirements and guidelines for center creation can circumvent turf wars occurring at the department, college, and university levels, when applying for internal as well as external funding.

Together with center/institute growth over the last ten years, there has been a growth in research space at US universities. Data recently released from the National Science Foundation show that research space at colleges and universities in the United States increased by more than 30 million square feet in the past ten years, representing an increase of 17 percent (June 2023). Specifically, academic institutions had 202.2 million square feet of science and engineering research space in 2011, which increased to 236.1 million square feet in 2021. Interestingly, five fields accounted for the vast majority of the research space in the 2021 data—biological/biomedical sciences, engineering, health sciences, agricultural sciences, and physical sciences.

Funding Sources for Research in Higher Education

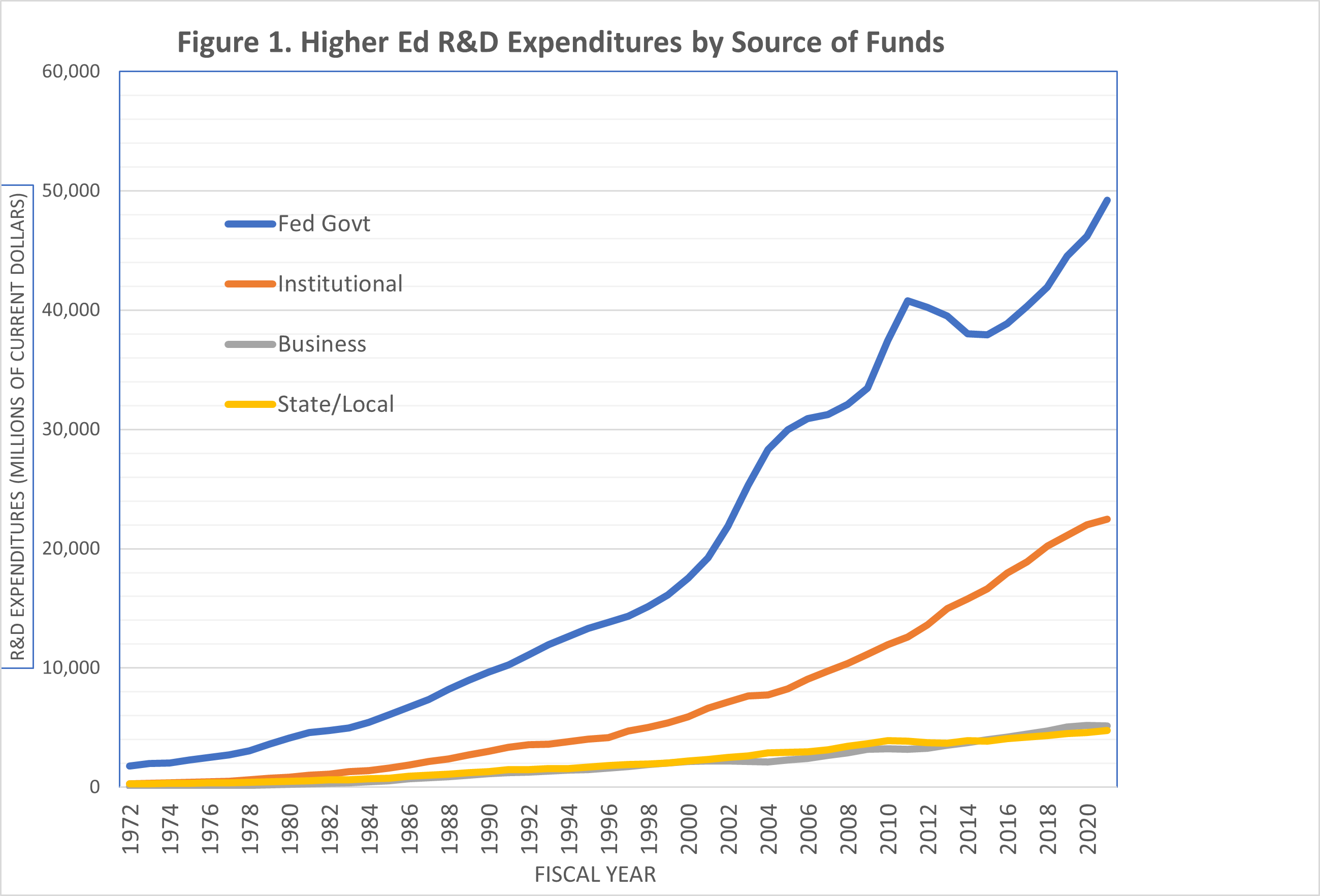

Funding of research in higher education has been tracked since 1953 by the National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics (NCSES) within the NSF. Each year, data is gathered for each institution as part of the Higher Education Research and Development survey (HERD 2021). It is important to note that the HERD numbers are self-reported research expenditures by each institution, albeit with some fairly strict guidelines and oversight of reporting by the NSF. If we consider the past twenty-one years (up to the year 2021, which is the most recent data available), all R&D expenditures had a significant uptick during those two decades. Figure 1 shows that the predominant source for those monies came from the US federal government, with $17.5 billion in 2000 increasing to $49.2 billion in 2021, an increase of 181 percent (HERD 2021).

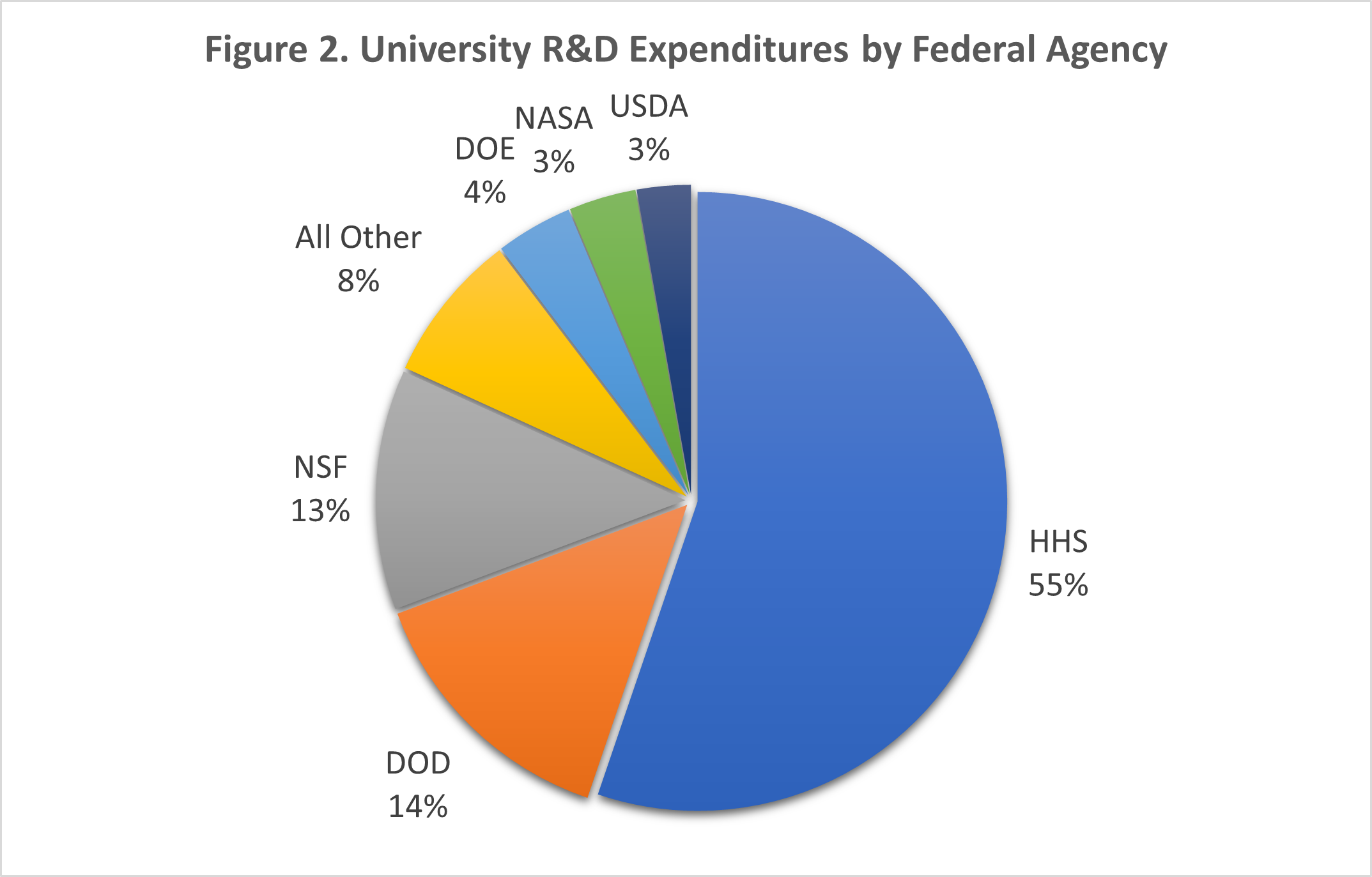

What federal agencies supply those funds to higher education institutions? Health and Human Services (97 percent of which comes from the National Institutes of Health [NIH]) provides the majority of the resources—nearly 55 percent of the federal pie (Figure 2). The NSF and the Department of Defense (DOD) each supply around 13–14 percent of the federal share of R&D. The Department of Energy (DOE), the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), and the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) each supply 2–4 percent of the resources to universities (HERD 2021). By and large, federal monies coming to universities are geared toward a health focus.

Among non-federal sources of support, institutional funds were the next largest source, followed by an equivalent amount from state/local government and business (Figure 1). What constitutes institutional funds and how are those funds used? NCSES categorizes these expenditures as unrecovered indirect costs, cost sharing, and direct funding for R&D. Many campuses also include start-up funding for new faculty in this category. It is noteworthy that institutional funds increased from 18 percent of total R&D in 2000 to nearly 25 percent of total R&D in 2021, perhaps resulting from increased start-up costs for new faculty and bridge funding for existing faculty. Direct funding for R&D is typically a small component of institutional funds for research, but it is vital to some disciplines which do not have traditional external sources for support. For example, small seed investments into the creative and performing arts can provide increased visibility and leverage for outside investments where an internal investment is needed. What stands out most starkly in Figure 1 is the minuscule amount of business support for research in higher education institutions, accounting for 5–7 percent of all R&D expenditures.

The publication R&D World comes out each year with the Global R&D Funding Forecast, which gives an overview of recent trends in global research and development as well as predictions for the future (R&D World 2022). This publication reports that in the US, the business sector is the largest funding source for R&D, amounting to $447 billion or 65.8 percent of R&D funds for 2022. Industry performs the most R&D in the US, doing 69.7 percent of the work for which $421 billion comes from companies and $52 billion from the federal government. Surprisingly, academia performs only about 14 percent of the R&D conducted in the entire United States.

Why is there not more investment by business in academic research? There have been several reasons put forward. First, the slower pace of academic research has been cited as a prominent reason—with the involvement of students and postdocs, they have other responsibilities like taking classes and teaching, that take their time away from research. We in academia don’t seem to get it, according to some industry partners, with respect to industrial timelines and milestones. Universities have also been labeled as “difficult to work with,” always haggling over budgets and adding extraneous costs to cover overhead.

There is a significant opportunity to garner greater business support of academic research, and many universities have met the challenge head on. There has been increasing attention paid to industry relationship building, particularly those industries in close proximity to university campuses. For example, Procter and Gamble, headquartered in Cincinnati, has built a close working relationship with the University of Cincinnati; Honda has a similar relationship with Ohio State University; and John Deere has partnered with the University of Illinois. Internal structures have been newly developed inside some universities to specifically court industry, such as corporate development offices, industry liaison offices, and similar offices. These internal university offices are often led by industry-experienced leaders who know the ins and outs of working with the corporate world. Some universities have seen marked success in building new industry partnerships, specifically by focusing on areas of shared interest and engaging faculty who understand the nuances of industry schedules.

The Importance of Reliable Data

Today, more than ever, university campuses need reliable sources of data. In my experience, campuses have a plethora of data sources—ranging from financial management systems to space management systems to differing email systems, and on and on. Most of these data systems do not talk to each other and there is local control over them. As many campuses migrate to new data management systems like Workday or Oracle, where some of the many existing data systems do talk to each other, the complexity of these tools is mind-boggling, the price tag enormous, and the time required to train on these new systems extensive. Often, in the transition, new data governance rules must be established.

In the monitoring and tracking of research, it is important to have robust and up-to-date data sources that you trust, enabling you to make informed decisions. The idea of homegrown data systems, while seemingly sufficient in the past, is no longer viable, because they require substantial resources to maintain. First, there are personnel required to keep these systems up to date, which siphons resources away from core mission areas. Second, if faculty are expected to keep their bibliographical information up to date, these staff personnel will spend their time chasing down faculty or in the end entering faculty data themselves. Some off-the-shelf systems provide automatically updated data beyond the scope of what a homegrown system could hope to provide. Third, homegrown databases require an increasingly sophisticated security apparatus to prevent data breaches. When all the costs for homegrown systems are calculated, it is often more economical and reliable to go with a commercial source that is based on the most up-to-date industry best practices.

There are several companies offering research tracking systems which can be immensely valuable to a research office and beyond. Examples of those companies include Huron, InfoReady, Wellspring, Cayuse, and Academic Analytics. Advantages of these commercial sources are that tracking of research is the core business of these companies, and the data are highly reliable. For example, disambiguation methods have been highly developed, such that faculty with similar names can be attributed to the correct institution. Often these companies provide data on faculty publications, citations, conference proceedings, books, book chapters, federal grants, patents, and clinical trials. Central to several of these products are tools for faculty development, such as suggested honorific awards, and funding opportunities as well as visualization of collaborative interactions. An attractive feature of using commercial sources for research data is the way the data are displayed. In many of the research data products now available, the graphics are of such high quality, they can be imported directly into conference presentations or board of trustee or regents materials. Thus, by using a commercial source for this type of data, the chief research officer can focus less on gathering the data and spend more time on data interpretation and follow-on actions. It is clear that having better data can help the chief research officer do more with the assets that they have on campus.

Another attractive feature of commercial research data sources is the ability to compare metrics for your campus with those of your peers. These true apples to apples comparisons are not possible with homegrown data systems or even data sharing between institutions. Many companies have gone to great effort to make the data comparable between schools so that true comparisons are possible.

Some examples of research questions that can be addressed by these powerful data systems:

- What is a good way to identify our true peers today and our aspirational peers of tomorrow?

- How does the overall research at our university compare with that of our peers?

- How do the infrastructure, facilities, equipment, faculty, and centers/institutes on our campus compare with those of our peers?

- How does our university compare with our peers in regard to federal, state, local, foundation, industry, and philanthropic funding?

- How do we compare with peers in the area of commercialization, e.g., patents, licenses, royalties, start-up companies, and venture capital funding?

- Who are the rising stars emerging among our faculty?

- How do our departments compare nationally?

- How do our strategic areas of research stack up nationally?

- Where are our alumni and what positions do they hold?

- How can our faculty be more recognized nationally?

- How can arts and humanities be more engaged in campus-wide research areas?

- What is our international research and collaboration profile?

Thus, these sorts of tools allow powerful research questions to be asked and answered, not only for curiosity’s sake or for bragging rights, but for strategic uses in planning. Discovering a pocket of faculty excellence distributed across campus can lead to new center formation in a unique niche area as well as expanded grant or philanthropic support.

References

Droegemeier, Kelvin K., Lori A. Snyder, Alicia Knoedler, William Taylor, Brett Litwiller, Caroline Whitacre, Howard Gobstein, Christine Keller, Teri L. Hinds, and Nathalie Dwyer. 2017. “The Roles of Chief Research Officers at American Research Universities: A Current Profile and Challenges for the Future,” Journal of Research Administration 48, no. 1, 26–43.

June, Audrey Williams. “Higher Ed’s Research Footprint Is Growing,” Chronicle of Higher Education, March 20, 2023. https://www.chronicle.com/article/higher-eds-research-footprint-is-growing

National Academies. 2008. “21st Century’s Grand Engineering Challenges Unveiled,” https://www.nationalacademies.org/news/2008/02/21-centurys-grand-engineering-challenges-unveiled.

National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics. 2021. “Higher Education Research and Development (HERD) Survey 2021,” https://ncses.nsf.gov/pubs/nsf23304.

National Science Foundation. n.d. “NSF’s 10 Big Ideas,” https://www.nsf.gov/news/special_reports/big_ideas/nsf2026.jsp.

R&D World Magazine. 2022 Global R&D Funding Forecast, https://forecast.rdworldonline.com/

United Nations. n.d. “Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development,” A/RES/70/1 https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf.