II. Learning and Success

Redesigning Higher Education Around Student Success

Dr. Bridget Burns

There are a significant number of barriers to college completion and student success, but most are merely a symptom of a singular underlying problem: higher education was never designed around students. This design failure shows up daily in systems and processes that students struggle to navigate. Isomorphism explains some of these persistent design challenges showing up in the lives of students across every sector or institutional type, and it also represents the greatest hope to address this issue. If higher education was never designed around students, and the solution is to center students (across various identities) in the design of the institution, the isomorphic design of institutions means that campuses can join forces to engage in this redesign work together rather than going it alone.

This essay will outline a specific change management strategy to address institutional redesign to improve student success for institutions navigating the complexity of managing and leading in a “post-Covid” workforce climate. The author will identify the key underlying design, cultural, and systemic issues contributing to the current state of national student outcomes for low-income and first-generation students and students of color, as well as provide solutions, recommendations, and a broader change management approach designed to support sustainable campus improvement that also represents a solution for the burnout epidemic facing administrators and staff in higher education.

Every student who enrolls in college should graduate with a degree or credential that positions them for social mobility, career success, and productive citizenship. This is not a revolutionary concept, but it is far from reality. Too many students who start college never finish. Completion rates today are only modestly better than they were forty years ago, while racial and socioeconomic gaps persist. In the 1970s, six out of every one hundred low-income students earned a bachelor’s degree. Fifty years later, that rate is around 12 percent. But for high-income populations, the attainment rate has doubled (Edsall 2012).

There are a number of barriers to college completion and student success, but most are a symptom of a single underlying problem: higher education was never designed around students.

The original model of higher education centered on the faculty (Rudolf 1990), but college design today is less intentional and more a collection of responses to externally imposed administrative requests and demands. This design failure shows up daily in systems and processes that students struggle to navigate.

Isomorphism—the similarity in structure between higher education institutions—explains some of this persistent design challenge, and it also represents the greatest hope to fix the problem (Cardona Mejia, Pardo del Val, Dasi Coscollar 2020). If higher education was never designed around students, and the solution is to center students (across various identities) in the design of the institution, it is likely that solutions that work in one institution can be modified or adapted to work in another, and campuses can collaborate to engage in this redesign work together rather than going it alone.

Institutional redesign is closely linked to innovation. Reorienting universities around students requires innovative mind-sets, practices, and habits, including a willingness to take many chances on improving the student experience knowing that a significant number of them will fail. Turning failure into an acceptable learning process can be enhanced by collaboration among universities—if institutions are willing to try new things together, the stigma of failure will be reduced while the benefits of success can be magnified.

These concepts are more than theoretical. For the past decade, a group of public research universities has worked together under the banner of the University Innovation Alliance (UIA) to develop, scale, and share innovations with promising potential to improve student success rates by redesigning university processes from a student perspective. In 2014, the UIA founding member universities committed to five core goals:

- dramatically increase the number of college graduates each university produces;

- produce far more low-income graduates;

- innovate together;

- hold down costs;

- and eliminate the disparity in outcomes across student populations.

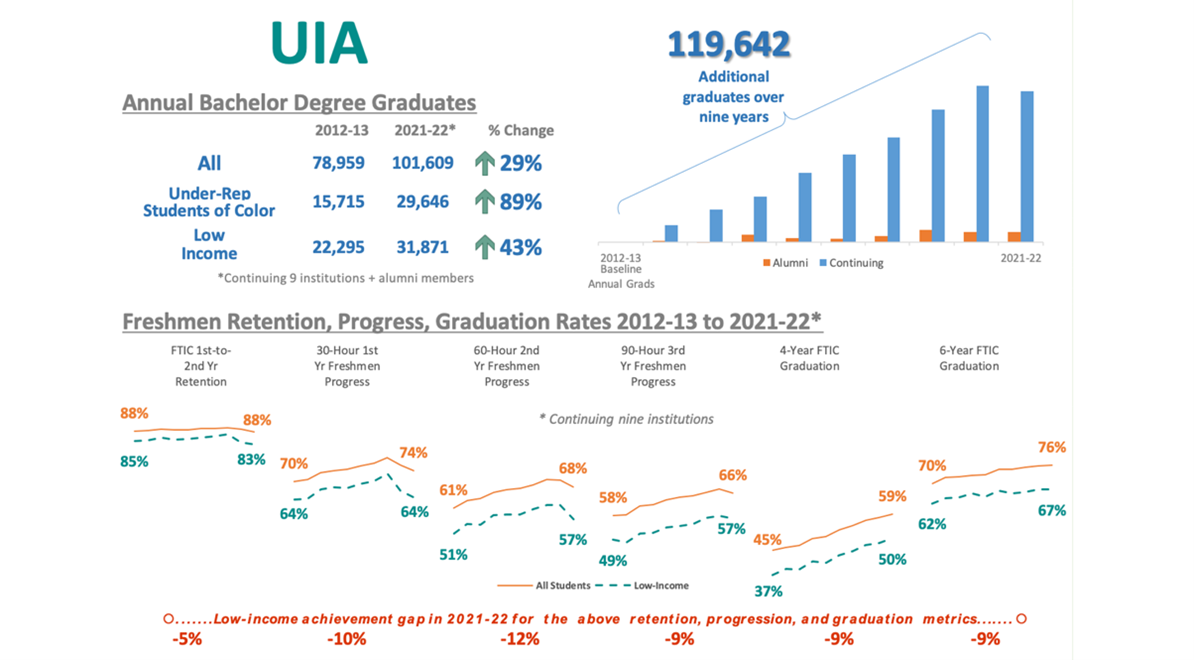

Through 2023, the founding UIA institutions had already graduated 119,642 additional students (beyond their stretch capacity at the time of founding), increased graduates of color annually by 89 percent, and increased low-income graduates annually by 43 percent.

Below is the annual data report for the University Innovation Alliance produced in June 2023 by the UIA’s external evaluator, Postsecondary Analytics.

Along the way, including through the pandemic, the UIA has learned lessons about high-impact collaborative innovation, how to effectively leverage and share learning from failure, and how to redesign institutions around the needs of students. New challenges constantly emerge, but UIA campuses have developed habits that allow them to keep making progress toward enrollment and completion goals, particularly for students of color and low-income and first-generation students. This chapter shares some of those insights as well as my perspective gleaned from working with institutions across the country.

Poor Design Holds Back Student Success

The process starts with understanding why higher education has struggled to help more students graduate. At the most fundamental level, it comes down to poor design—or at least, a design that is poorly suited to today’s students, who live in a world in which nearly every consumer-facing product is designed with the user experience in mind. Most people have experienced or grown accustomed to better user interfaces. From Uber to DoorDash to Netflix and even banks, services today are designed to be navigated easily and provide results tailor-made for consumers.

Compare the user-centered experience of these well-known companies to the experience of a first-generation or low-income college student. Most arrive on campus with high expectations that the university will direct them to good outcomes. Yet they soon discover how difficult it is to receive adequate direction. No one steps forward to answer questions like: When do you meet with an academic advisor? How do you reconcile a financial aid hold? How do you know—before it’s too late—if you’re on track or off track? Administrators with decades of experience in university processes may think the path is clear, but complex structures and coded language create barriers for students and make them feel unwelcome. Unfortunately, poor design has persisted because the historic culture of higher education places the blame for any failure on the shoulders of the student rather than seeing design flaws for what they are (Burns 2023).

Collaborative Student-Centered Redesign Is the Answer

To fix this situation and help more students graduate, universities need to change. But of course, change is difficult for any organization, and especially for complex bureaucratic organizations with massive multi-billion-dollar footprints. Universities were designed to last, not to change. Therefore, it is my recommendation that in order to achieve the changes needed to better serve students and position institutions to thrive in the future, they should work together.

Collaboration is not always an easy path for organizations, especially ones existing in a competitive environment with different cultures, identities, and leadership. At the same time, it’s nearly impossible for universities to sustain organizational change unless a visionary and powerful president or chancellor remains on the job long enough to outlast those who are resistant to change within their organization. These leaders exist, but they’re rare; the average presidency is now just 5.9 years, according to the American Council on Education (Jesse, 2023). To help overcome the tendency for innovation to flag when an individual leader leaves an institution, universities should collaborate with each other, building infrastructure and momentum for student-centered innovation that can last through multiple administrations on any particular campus.

When to Collaborate and with Whom

Not all collaboration is created equal in higher education. There are many experiences dubbed “collaboration” that merely represent additional unpaid work that is expected of the collaboration partners and ends up being far more difficult than working alone. What I’m proposing is an authentic collaboration that is sustained over time, adds relatively equal value to all partners, and achieves significant change or impact. Smart, well-directed collaboration typically needs a spur. At the UIA, we’ve determined that the most effective collaboration happens for three reasons: (1) there is a shared problem that does not have a solution, and all partners want to find a solution; (2) there is a big goal that all parties aspire to, yet none of them can accomplish that goal alone; and (3) the partners in the collaboration are advancing a shared vision that they develop and refine together—no institution should feel pressured to participate by funders, associations, or other outside entities.

How do you find presidents and chancellors who meet these criteria and are eager to collaborate? Look for those who are signaling a shared sense of frustration with a problem you want to solve, or are talking about an objective you care about. Then start with smaller conversations among select groups. At national meetings and conferences, you’ll likely find that the best conversations with potential allies happen away from the main stage, in the hallway, at dinners, or in places where a microphone is not present. Presidents are rarely able to be candid until they know and trust each other, and those relationships are best built over time.

The UIA was formed when the New America Foundation’s Next Generation Universities report signaled potential shared interests among the six institutions profiled (Selingo, Fishman, Palmer, and Carey 2013). Each was noted for its commitment to expanding access and improving outcomes for students while also pursuing world-class research. Using the Next Generation Universities list as a kick start, Arizona State University President Michael Crow invited a small group of presidents to a side meeting at another event to discuss what they might do together for the future of the United States. The report served as a signal of shared interests and spurred President Crow to follow up with a discussion among a small select group of like-minded leaders to determine where there was potential for collaboration—and the UIA was born. There are many ways to identify potential partners for student success redesign work—for instance, other campuses using the same technology partners your campus uses, or small affinity groups formed at association meetings. The important thing is to identify common bonds and goals and start to build the trust required for effective collaboration one conversation at a time. Once all the partners have agreed on a basic premise, start with a small project or collaboration to test the waters and determine if your vision and values are as aligned as you initially supposed.

Innovating for Twenty-First-Century Students

Organizational change is difficult work, but collaboration is an effective vehicle to build momentum, hold your institution accountable, and hopefully save time and money along the way. The organizational change work higher education urgently needs institutions to embark upon is that which enables campuses to redesign their systems and student-facing processes around the needs of today’s students.

The traditional eighteen- to twenty-two-year-old student isn’t necessarily the norm, especially at public universities. Demographic trends show this population shrinking. Meanwhile, for the first time in US history, low-income students are the majority in public K-12 schools, resulting in a pipeline of potential students coming from a low-income background (Layton, 2015; Southern Education Foundation, 2015). Reimagining education for people who are adults, parents, caregivers, transfer students, full-time workers, low-income, first-generation, and students of color is an ideal place for collaborative efforts between colleges, because of the universality of the challenge, and the historic universality of our sector’s failure to serve these students well.

Beyond demographics, other factors about students, and about their expectations of higher education, are changing. The students of today and the future will be the most sensitive to bad design of any generation that’s come before. As a result, they’re less likely to tolerate a poorly designed education experience. If something isn’t working for them, such as a mystifying advising and registration process or an incomprehensible financial aid package, they will clearly get the message that the university isn’t committed to their success and they may look for better options elsewhere—perhaps outside of traditional higher ed altogether.

Finally, more students will be looking for options beyond traditional degree programs. Whether certifications or accelerated programs, students who are older, more career-focused, and pressed for time will be seeking credentials that provide tangible, career-enhancing skills that can be completed as flexibly as possible, perhaps even as they weave in and out of higher education over many years. Institutions should be constantly listening and innovating to provide the skills, competencies, certificates, and badges students want. This is fundamental to serving and supporting learners at every stage of their life.

Steps to Advance Student-Centered Learning

Many university leaders, especially new leaders, want to instill a more innovative, problem-solving culture among their team but don’t know where to start. Your team needs more guidance, but you’re understandably busy doing your own overwhelming job and can’t provide constant direction. The following steps grew out of my accumulated experience with the UIA and can help you point your team in the right direction.

Steps to scale:

- Find an example you can learn from. Look to universities that have solved similar challenges and find out how they approached the work.

- Find a guide or mentor you can learn from.

- Determine where you are starting from.

- Be intentional about educating everyone at your campus about what you are trying to do. Do not limit the learning to a small group of people who will be doing the work—they will at some point need friends and allies, and many of them will transition.

- Be intentional about ensuring that the journey the campus is on is not just known about or owned by a select group.

- Form a cross-functional team that includes a variety of thinkers, doers, and people who will impact the change.

- Staff the team with a project manager or equivalent to ensure the work happens between meetings.

- Be intentional about meeting agendas to ensure they are high-impact and bring significant value to everyone who attends. The focus should be very high level and there should be a dashboard or data points the group is constantly monitoring.

- Be intentional about the kinds of habits that will help the team or campus be successful: a weigh-in, annual reporting, and meaningful connection-building experiences.

- Backward plan where you want to be in six months, a year, or two years.

- Start by process mapping in a community environment to get everyone on the same page about the area you are working on.

- Once you see the challenges, you will identify some low-hanging fruit associated with the process or topic.

- Take action on the low-hanging fruit and be explicit that this is connected to what you are scaling so people feel good about the experience and start to associate this work with action and fulfillment.

- Create a calendar of the additional areas to take action on in the coming months, and be sure to celebrate victories along the way and share about the courage and bravery of those doing the work.

- Spread the love and celebrate those who contributed. The more people shine a light on the work of others, the more they keep coming back for more, and this type of activity gets the reputation for being one that gives satisfaction and opportunity.

Solutions: Designing a Student-Centered Innovation Process

Redesigning higher education to promote student success will require subtle culture change and shifts to normalize a consistent focus on capturing empathy and learning from the lived experience of today’s students, coupled with consistent design experiences that enable professionals to walk through the actual systems and processes students are wading through. The early steps are low cost and will make the most difference in the long term for your campus, but the challenge is instilling consistency of practice and orienting your culture toward becoming a learning organization rather than merely being focused on efficiency.

The following steps are essential and underlie every broader complex innovation solution referenced afterward:

- Empathy sprints: Empathy is the first step of design. Attend any experience hosted by the Stanford d. School and you will hear this mantra over and over. You cannot create good experiences and solutions for someone you do not understand. Employees should be expected to speak to at least one or two students in the week prior to coming to a meeting with leadership. There should be a portion of the agenda where people go around and share what they learned that surprised them, or share the specific topics they heard students offer commentary on. This cannot just be a one-time thing. It needs to become a part of who you are as an organization—you are now a university that is curious and wants to hear from students themselves rather than relying on data and observations offered secondhand.

- Process mapping sessions: An effective, action-oriented way to bring together everyone working on a problem is to engage in an exercise called process mapping, which entails going through all the steps a student must take to successfully navigate a university process. Process mapping is a simple activity with limited cost, but leaves any organization with a better understanding of the user experience and enables groups of people to see the system failures and process hurdles more clearly than they can in their day-to-day roles (Aljets and Burns 2018). The humble sticky-note is vital to process mapping and turns out to be one of the most powerful innovation tools at our disposal. Everyone on the process mapping team writes out on sticky-notes the touchpoints a student has with their office. Detail is key. Every interaction should be surfaced. The sticky-notes help visualize the process and illuminate how many different steps a student must take to get from point A to point B. The new map replaces the administration’s vision of how a process works with the student’s experience of how it works—and it’s always revealing.One example of process mapping I frequently cite comes from Michigan State University (MSU). After attending the first convening of the UIA hosted at Georgia State University (GSU) where GSU administrators talked about their experiences with process mapping, the MSU team put the idea to work. They were concerned that they were sending newly admitted students an overwhelming number of emails between admission and arrival on campus. By bringing together various offices responsible for communicating with new students and using sticky-notes to log all the emails they were sending, they soon discovered that a newly enrolled student could receive as many as 450 emails from the university by the time they got to campus. New students—particularly first-generation or low-income students with limited support networks—would have little way to prioritize which were most important and which could wait until later. Identifying these challenges created clarity, and alignment, and elevated new topics for further refinement, review, and improvement across the institution (Aljets and Burns, 2018).In just one exercise, administrators were able to identify a challenge and craft a solution to help students engage more easily with the institution. Furthermore, they did so in a way that brought connection and purpose to administrators (“We are solving an actual problem!”). It’s a process that can be repeated again and again, seeking student input as often as possible. Leaders can also signal their approval and encourage progress and proper mind-set by asking at the end of each exercise, “What did we learn?” Focusing on learning destigmatized whatever problems were revealed. What’s important now is how to innovate and improve.

- Clarify and prioritize your challenges: Pursue innovations and solutions that address the problems on your campus. Do not pursue innovation for innovation’s sake. Whatever challenge you aim to address, this is a moment in time where there are many important and effective solutions worth embracing, and regardless of an institution’s funding, governance structure, state policies, or leadership, there are specific low-cost actions universities can take to cultivate greater empathy, problem recognition, and diagnosis to improve outcomes for students.

- Set ambitious but realistic goals, and establish a scoreboard and cadence for assessment: Many campuses struggle to make progress for an array of reasons, but one aspect rarely missing from successful efforts is a clear goal that is set by the organization and consistently reiterated as a north star, coupled with a consistent habit of revisiting and reviewing progress toward that goal. When reviewing progress, ensure that the goal you are working on is treated separately and not one of fifty metrics being reviewed at the same time as you look at research numbers, athletic outcomes, budget formulas, and any other area you might also be working to improve. The conversation about improvement needs to enable a level of focus that is difficult when the conversation is crowded by unrelated topics.

In 2014, UIA campuses set individual campus goals that were combined into a collective ten-year goal that was announced by President Obama at the 2014 White House College Opportunity Summit: we were committed to producing 68,000 more graduates than our current and stretch capacity at the time, and at least half of those additional graduates were going to be from low-income students by 2025 (Obama 2014). Although this goal was ambitious for us at the time, the more important aspect was that it was set by each campus leader and not imposed upon them. Conversely, there are many examples of state and institutional goals that were not set by the people leading the work, and there can be a lack of buy-in toward that goal which results in less likelihood of success. At the UIA, our measures may be imperfect, but we use them consistently and intentionally. We review our collective data one time per year and always in the same format, focusing on the measures agreed upon by the campuses: student outcomes across income and race at the 30-, 60-, and 90-credit-hour threshold. We are focusing on equity gaps and progress for improvement in addition to annually capturing graduation data. Whatever your goal, make sure you create a consistent dashboard you review and reflect upon to make consistent progress.

Insights from UIA Collaborations

UIA members have collaborated on a series of demonstration projects designed to make each campus more student centered and remove specific barriers students face. Areas of focus have included predictive analytics, proactive advising, financial aid, career readiness, and academic recovery. In each, UIA campuses advanced innovations that can keep students enrolled and on the path to graduation.

For instance, by using predictive analytics and proactive advising, UIA members gained greater insight into which courses gave students the greatest difficulty, and where students went off track in their progression toward a degree. The data produced rich insights into the student experience, revealing which students were struggling, the courses most likely to stymie a particular student, the most challenging instructional modality for that student, and even the time of day a student is most likely to struggle in class.

Insights derived from predictive analytics can be integrated with other university systems, such as course scheduling and academic advising. In this way, the university can be more responsive to student needs at the macro level—for instance, by anticipating which courses large numbers of students will need to take and scheduling classes at the times students need to take them—and at the micro level—for instance, by spurring proactive communications with students to ensure they’re accessing the resources they need to schedule and succeed in the classes they need to progress and graduate. In the UIA’s project, academic advisors were equipped with data derived from predictive analytics, allowing them to proactively reach out to students through a series of automated and personalized prompts, helping the students avoid falling behind in their degree programs and guiding them back on course (or toward a different path). Furthermore, when advisors know a student has struggled, or is likely to struggle, in a particular class, they can connect the student with additional wraparound services to make successful course completion more likely.

The UIA’s financial aid innovation involved providing completion grants—small (less than $1,000) financial awards that allowed students who were close to graduation to remain enrolled, finish their required coursework, and graduate rather than disenroll close to the finish line due to financial hardship. While implementing the completion grant project, UIA members gained greater insight into the variety of financial holds placed by offices across campuses for such minor issues as overdue library fees and parking fines. On many campuses, these hold categories were rarely reviewed and had proliferated over time to number in the dozens—each a potentially unnecessary obstacle to student success. Simply shining a light on this reality helped campuses initiate processes to review and remove these financial hurdles.

The UIA’s career readiness work revealed a key insight across multiple universities: The only place all students go is to the classroom, so career preparation should be integrated into the classroom, not simply offered as a standalone, separate function students are expected to pursue outside of class. Faculty should be equipped with career readiness expertise and support. For instance, career readiness personnel can offer suggestions for how faculty can integrate career readiness into classroom work. Furthermore, career readiness needs to start on day 1, not in junior or senior year. It’s important to help students think early and often about how their classroom learning can be leveraged to support their career aspirations. And students should be given more opportunities to experience potential careers through internships and related work—preferably paid internships to overcome equity challenges.

At root, each of these interventions and adjustments requires centering and prioritizing students’ needs in everything the university does. At a time when we are thinking more deeply than ever about how to ensure students’ social and emotional well-being—in addition to their academic success—knowing the university has their back and wants them to succeed can be a great relief to students. Whatever else may be going on in a student’s life, alleviating the fear of academic failure or financial struggle, and equipping students with the tools to succeed in the classroom and prepare for a successful career after graduation can ease mental burdens and help students feel more empowered to control their college experience.

What Gets in the Way of Progress

There are several obstacles that get in the way of innovation, delay change, and impede progress on closing achievement gaps. Currently, the biggest impediment to change and innovation is turnover and transition, as well as our lack of planning for either. The constant shuffle without any plan for sustainability means institutions stop and start efforts and waste energy with limited progress. This can be overcome with a consistent cultural practice of co-captains for every project, initiative, and strategy, and by designing around turnover as a feature of the system, not a bug.

In addition, higher education’s persistent bias toward quantitative data over qualitative data and the lack of a singular office or role tasked with the sole purpose of listening to the challenges students face contribute to the lack of empathy required to engage in systemic change. Addressing student success challenges and growing equity gaps requires institutions to recognize that student identities and experiences are not a monolith; instead, the institution needs to engage in specific practices to support a greater understanding of the complexity and nuance of the needs of different student populations.

Universities also need to take a hard look at what they expect from the people who work in higher ed. Capacity deficits and burnout are major challenges confronting university staff. Administrator fatigue has been building for many years. Paperwork burdens have proliferated as boards, presidents, accreditors, legislators, and others require reporting on a plethora of issues, only some of which may feel particularly meaningful or useful. Time and resources have not kept pace. Higher education as a field suffers from the mistaken assumption that if we give an administrator a new task, their plate will expand to accommodate it.

The result is that work and committees tend to be task-oriented rather than goal-oriented. There is little unstructured time for individuals or action-oriented teams to generate new ideas or a game plan how to move a good idea forward—both critical to innovation. The pandemic added stresses, including, of course, the existential stress of living through a major health crisis, but also the small daily stresses of reduced human interaction, to which Zoom calls were a very imperfect remedy. The literature—and years of experience—suggests that for people to thrive at their work they need community, purpose, and inspiration (Moss 2021). All three have been in short supply in recent years. Making real progress on student success outcomes requires a changed management approach intentionally designed to overcome transition, turnover, and burnout.

Conclusion

Advancing student-centered innovation will require strong leadership with a clear vision and direction repeated consistently. A key message should be that iteration and failure are okay. Not every idea has to be fully vetted before moving forward, but it should be informed by student input and seek to solve actual problems students are confronting. When an idea doesn’t pan out, it shouldn’t be hidden; it should be discussed and studied to surface lessons that can be applied to the next iteration—or to a completely different problem.

In addition to fueling innovation, being honest about failure also opens the door to genuine collaboration with other universities. The University Innovation Alliance has found that the key to collaboration between institutions is not comparing peaks, but sharing valleys. Because of isomorphism, most institutions are grappling with similar problems, particularly when it comes to student success—and most leaders and administrators are hungry for solutions.

Fortunately, isomorphism also makes it easier to transfer successful ideas from one campus to another. Innovation isn’t a cut-and-paste endeavor, but rather an understand-and-adapt process of taking an intervention that has worked in one place and shifting it to work within your structure and systems. Acknowledging common failures across institutions will help build the community that makes common success possible. Clearing away the stigma around failure and overcoming the idea that all good ideas must originate at your own institution will make it possible to adopt innovative practices and innovative touchstones from other places and put more innovation shots on goal, which is vital to generating innovation wins.

In addition to benefiting students, innovating to improve the student experience can bring community, purpose, and inspiration back to the people working at the university. Effective innovation processes require people to engage in community-oriented activities. Innovation itself provides purpose as people work together toward a common improvement goal. And the idea of helping students succeed is what inspired most people to work in higher education in the first place.

The key is to break out of old habits. Because innovation is new work, universities shouldn’t feel bound to approach it the same way they’ve approached projects in the past. Innovation can and should be pursued in ways that promote collaboration, acceptance of failure, meaningful engagement with other universities, and community, purpose, and inspiration for the people working on it. While innovation in a large institution isn’t easy, it is deeply rewarding—especially when the beneficiaries are students who finally see that the university is working with them to help them achieve their college and life goals.

References

Burns, Bridget, 2023. “Fostering Change in Higher Education,” Trusteeship, Nov-Dec 2023, https://agb.org/trusteeship-article/fostering-change-in-higher-education/

Burns, Bridget and Alex Aljets. 2018. “Using Process Mapping to Redesign the Student Experience,” Educause Review, March 26, 2018, https://er.educause.edu/articles/2018/3/using-process-mapping-to-redesign-the-student-experience.

Cardona Mejía, Liliana Maria, Pardo del Val, Manuela, and Dasí Coscollar, Maria del S. Angels. (2020). “The Institutional Isomorphism in the Context of Organizational Changes in Higher Education Institutions,” International Journal of Research in Education and Science 6, no. 1 (2020): 61–73.

Edsall, Thomas B. 2012. “The Reproduction of Privilege.” New York Times, March 12, 2012. https://archive.nytimes.com/campaignstops.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/03/12/the-reproduction-of-privilege/

Jesse, David. 2023. “Portrait of the Presidency: They Are Less Experienced than Ever- and Eyeing the Exits,” Chronicle of Higher Education, April 14, 2023. https://www.chronicle.com/article/college-presidents-are-less-experienced-than-ever-and-eyeing-the-exit

Layton, Lyndsey. 2015. “Majority of US Public School Students Are in Poverty,” Washington Post, January 16, 2015. https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/education/majority-of-us-public-school-students-are-in-poverty/2015/01/15/df7171d0-9ce9-11e4-a7ee-526210d665b4_story.html

Moss, Jennifer. 2021. The Burnout Epidemic: The Rise of Chronic Stress and How We Can Fix It. Boston: Harvard Business Review Press.

Obama, Barack. 2014. “Remarks by the President at the College Opportunity Summit,” December 4, 2014. Retrieved from https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2014/12/04/remarks-president-college-opportunity-summit.

Reardon, Sean F. 2011. “The Widening Academic Achievement Gap between the Rich and the Poor: New Evidence and Possible Explanations.” edited by R. Murnane and G. Duncan Whither Opportunity? Rising Inequality, Schools, and Children’s Life Choices: 91–116. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Rudolph, Frederick. 1990. The American College and University: A History. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press.

Selingo, Jeff, Rachel Fishman, Iris Palmer, and Kevin Carey, 2013. “The Policy Paper of the Next Generation University,” New America Foundation, May 21, 2013. https://www.newamerica.org/education-policy/policy-papers/the-next-generation-university/

Suitts, Steve. 2015. “New Majority Research Bulletin: Low-Income Students Now a Majority in the Nation’s Public Schools,” Southern Education Foundation Research Bulletin, January, 2015. https://southerneducation.org/wp-content/uploads/documents/new-majority-update-bulletin.pdf