Mechanisms of Social Movement Suppression

What You’ll Learn

- How the US suppresses social movements

- What COINTELPRO (Counter Intelligence Program) was and the mechanisms employed to suppress social movements of that era

The US has a long history of interference, including on its own soil in the form of suppressing the efforts of social movements and, in particular, liberatory and leftist social movements. Labor organizing, independence, civil rights, and environmental movements have all been subject to opposition by the US government, often at the behest of or in cooperation with large corporations.

In trying to grapple with the risks associated with a social movement not attending to digital security, it is helpful to look at how the State has interfered with social movements in the past. This history can be overwhelming, and it can be tempting to dismiss this as something that has happened in the past but that is not happening now. Going through this history can also lead to defeatism, especially in light of the additional digitally enhanced tools that the State can employ against an adversary (perceived or actual).

However, since we should not condemn ourselves to repeat mistakes of the past, we need to attend to enough history to learn appropriate lessons so that our movements may be successful moving forward. In order to do so without turning this into a history textbook, we draw on the scholarship of Jules Boykoff, who categorized the ways in which the US has messed with social movements in the twentieth century. Boykoff enumerated twelve modes of suppression, which we compress to seven in this presentation.

Understanding these historical modes will allow us to predict how digital surveillance could support or enhance those modes, as we will discuss in the chapter “Digital Threats to Social Movements.” But more importantly, we will be able to see how encryption and attending to digital hygiene can protect social movements against (some of) these oppositional forces, as we will cover in part 3 of this book.

Modes of Suppression

These are seven ways in which the US has suppressed and continues to suppress social movements, each with a few examples of its use. Unfortunately, these examples are far from exhaustive.

1. Direct Violence

Beatings, bombings, shootings, and other forms of violence are carried out by the State or other institutions or nodes of power against dissident citizens.

This may be the result of the policing of large groups (such as when the Ohio Army National Guard fired at students during an antiwar protest at Kent State University, killing four people and injuring nine others) or targeted assassinations (such as in the FBI-organized night-raid shooting of Black Panther Party leader Fred Hampton). To risk an understatement, these actions discourage participation in social movements for fear of life and limb.

2. The Legal System

The legal system allows for harassment arrests, public prosecutions and hearings, and extraordinary laws that are used to interfere with individuals in biased fashions. The State arrests activists for minor charges that are often false and sometimes based on obscure statutes that have remained on the books, buried and dormant but nevertheless providing vessels for selective legal persecution. Public prosecutions and hearings can land dissidents in jail or consume their resources in legal proceedings that sidetrack their activism and demobilize their movements. Current supporters and potential allies are discouraged from putting forth dissident views. Prosecution and hearings publicized in the mass media reverberate outward into the public sphere. Another form of legal suppression, the State promulgates and enforces exceptional laws and rules to tie up activists in the criminal justice labyrinth. This is the legal system being used to squelch dissent.

Controversial stop-and-frisk programs allow police officers to briefly detain and at times search people without probable cause. Free-speech zones greatly limit the time, place, and manner of protests. Those arrested at First Amendment–protected protests on the inauguration of Donald Trump faced public prosecutions that were unlikely to ever reach a conviction. And certain crimes, such as arson or the destruction of property, are elevated to terrorism when they are accompanied by a political motive and allow for the State to greatly increase the punishment doled out. Other laws are specifically tailored to prevent activism, such as “ag-gag laws,” which criminalize the filming of agricultural operations (which is done to expose the abuse of animals).

3. Employment Deprivation

One’s political beliefs can result in threats to or actual loss of employment due to one’s political beliefs or activities. Some dissidents are not hired in the first place because of their political beliefs. This is typically carried out by employers, though the State can have a powerful direct or indirect influence.

Recently, we have seen university professors forced out of their jobs or have job offers revoked, as with Steven Salaita, whose offer of employment as a professor of American Indian studies was withdrawn following university donors’ objections to a series of Tweets critical of Israel and Zionism. For several years (but since struck down by a federal court), government contractors in Texas were required to sign a pledge to not participate in the pro-Palestinian Boycott, Divestment, and Sanction movement or else they would have their contracts canceled; this resulted in the firing of an American citizen of Palestinian descent who worked as a school speech pathologist and refused to sign the statement.

4. Conspicuous Surveillance

Conspicuous surveillance aims primarily not to collect information (which is best done surreptitiously) but to intimidate. This is intended to result in a chilling effect, in which individuals guard their speech and action out of fear of reprisal. It may drive away those engaged in activism or make it difficult to encourage new activists. Although the chilling effect has been deemed unconstitutional, it is difficult to prove harm in a court (as required), so it is a safe means of suppression (from the perspective of the surveiller).

The FBI has a long history of “knock and talks” or simply visiting the houses of dissidents and activists (and those of their families and employers) to “have a chat” in order to let people know that they are being watched.

5. Covert Surveillance

Surveillance might be concentrated or focused, as with the use of spies, targeted wiretaps, and subpoenas or warrants for data; the use of infiltrators (covert agents who become members of the target group); or the use of informants (existing group members who are paid or threatened in order to extract information). Surveillance might also be diffused, such as the accumulation, storage, and analysis of individual and group information that is obtained through internet monitoring, mail openings, and other mass-surveillance techniques.

The scale of the FBI informant program is sizeable, having over fifteen thousand informants in 2008. In the wake of 9/11, the FBI and large law enforcement agencies such as the NYPD turned their intelligence programs against Muslim American communities. This included the close surveillance of lawyers, professors, and the executive director of the largest Muslim civil rights organization in the US (the Council on American-Islamic Relations) by the FBI. The NYPD singled out mosques and Muslim student associations, organizations, and businesses through the use of informants, infiltrators, and surveillance. The NYPD’s supposed rationale was to identify potential “terrorists” by looking for “radicalization indicators,” including First Amendment–protected activities such as “wearing traditional Islamic clothing [and] growing a beard” and “becoming involved in social activism.”

6. Deception

Snitch jacketing is when a person (often an infiltrator) intentionally generates suspicion that an authentic activist is a State informant or otherwise maliciously present in a social movement group. Infiltrators or informants who are in place to encourage violence or illegal activities or tactics (rather than simply report on activities) are known as agent provocateurs and do so in order to legally entrap or discredit the group. False propaganda is the use of fabricated documents that are designed to create schisms or undermine solidarity between activist organizations. These controversial, offending, and sometimes vicious documents are meant to foment dissension within and between groups.

FBI infiltrators have acted as agent provocateurs by leading them down a path to illegal activity that they would not have otherwise followed. Mohamed Mohamud was an Oregon State University student who was contacted by an undercover FBI agent who over a period of five months suggested and provided the means to bomb the lighting of the Portland Christmas tree on November 26, 2010. The bomb was a fake, but Mohamud was sentenced to thirty years of imprisonment.

Eric McDavid spent nearly nine years in prison for conspiring to damage corporate and government property after a paid FBI informant acted as an agent provocateur, encouraging McDavid’s group to engage in property destruction and providing them with bomb-making information, money to buy the raw materials needed, transportation, and a cabin to work in. McDavid’s conviction was overturned due to the FBI failing to disclose potentially exculpatory evidence to the defense.

7. Mass Media Influence

There are two major types of mass media manipulation: (1) story implantation, whereby the State makes use of friendly press contacts who publish government-generated articles verbatim or with minor adjustments, and (2) strong-arming, whereby the State intimidates journalists or editors to withhold unwanted information from reaching publication. In addition to that, mass media deprecation portrays dissidents as ridiculous, bizarre, dangerous, or otherwise out of step with mainstream society. This is often not so much due to conspiracy as to dutiful adherence to journalistic norms and values. Mass media underestimation occurs when activists and the State come up with discrepant estimates of crowd sizes for protests, marches, and other activities, with the mass media tending to accept the State’s lower numbers. The mass media may also falsely balance dissidents with counterdemonstrators. Many dissident efforts never make it onto the mass media’s agenda or are buried in the minor sections of the newspaper. Not only the State but also powerful media organizations or individual owners are able to carry out this type of suppression.

Following the invasion of Iraq after 9/11, antiwar sentiment was consistently downplayed through underreporting. As just one example, the September 2006 antiwar protests that saw more than two hundred thousand people take to the streets across the US was reported by the Oregonian in this way: A one-hundred-thousand-strong antiwar protest in Washington, DC, was reported on page 10, along with an article on a Portland protest. The article estimated one hundred people at the protest, even though aerial evidence pointed to over three thousand. A counterdemonstration to the Washington, DC, antiwar protest was covered on page 2 with a larger photo and longer text, even though only four hundred people attended.

Information Technology Interference

This resource would be lacking if we didn’t talk about censorship and other interference with information technology. It is an additional mode of suppression with particular relevance to the Information Age that dovetails with deception and mass media influence, wherein access to the internet or related infrastructure is blocked or otherwise denied to social movements—for example, cutting off internet or mobile network access during a protest, censoring certain sites or types of internet traffic, or shutting down a social movement group’s website.

Boykoff does not include this in his catalog of suppression, since its use is not widespread within the US by the US largely due to the country’s constitutional protections. However, its use is widespread around the globe. Governments have been known to cut off internet access at the country level (such as the week-long total shutdown of the internet in Iran as a means to suppress protests) or limit access to certain sources (such as the Great Firewall of China blocking Google, Facebook, Twitter, and Wikipedia). US companies also participate in this, complying with foreign censorship: Zoom (a web conferencing service) shut down the accounts of three activists at the behest of China, who had planned online events to commemorate the Tiananmen Square massacre.

In Context: COINTELPRO and the COINTELPRO Era

From the 1950s through the 1970s, the FBI conducted a set of secret, domestic counterintelligence activities, which became known as COINTELPRO, under the leadership of FBI director J. Edgar Hoover. Originating with US government anticommunist programs during the Red Scare, COINTELPRO aimed to “disrupt, by any means necessary,” the organizing and activist efforts of the Black Power, Puerto Rican independence, civil rights, and other movements. With respect to civil rights and Black Power movements (including the activities of Martin Luther King Jr.), COINTELPRO was ordered to “expose, disrupt, misdirect, discredit, or otherwise neutralize the activities of black-nationalist, hate-type organizations and groupings, their leadership, spokesmen, membership and supporters to counter their propensity for violence and civil disorder.”

COINTELPRO was exposed through the theft of boxes full of sensitive FBI paperwork obtained through a burglary in 1971 by the Citizens’ Commission to Investigate the FBI, the members of which only went public in the wake of Ed Snowden’s disclosures, with remaining COINTELPRO documents coming to light through Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests. The commission’s leak resulted in the formation of the US Senate’s Church Committee in 1975, which castigated the FBI for the “domestic intelligence activities [that] have invaded individual privacy and violated the rights of lawful assembly and political expression” and ultimately shut down COINTELPRO. The Church Committee prefaced their admonishment this way:

We have seen segments of our Government, in their attitudes and action, adopt tactics unworthy of a democracy, and occasionally reminiscent of totalitarian regimes. We have seen a consistent pattern in which programs initiated with limited goals, such as preventing criminal violence or identifying foreign spies, were expanded to what witnesses characterized as “vacuum cleaners,” sweeping in information about lawful activities of American citizens. The tendency of intelligence activities to expand beyond their initial scope is a theme which runs through every aspect of our investigative findings. Intelligence collection programs naturally generate ever-increasing demands for new data. And once intelligence has been collected, there are strong pressures to use it against the target.

All the following modes of suppression were used by the FBI or support partners as part of COINTELPRO or against COINTELPRO targets:

1. Direct violence

The murder of Fred Hampton mentioned above was a joint operation of the FBI and Chicago Police Department. Fred Hampton was the chairman of the Black Panther Party, a revolutionary socialist political organization of the late 1960s through 1970s that aimed to protect Black Americans and provide social programs (such as free breakfast and health clinics). The Black Panther Party (BPP) was labeled as a “Black nationalist hate group” by the FBI for inclusion as a COINTELPRO target. Hampton’s assassination was supported by other modes of suppression, including the following:

- Covert surveillance. A paid FBI infiltrator provided intelligence that made the raid leading to Hampton’s murder possible.

- Deception. The same infiltrator created an atmosphere of distrust and suspicion within the BPP in part by snitch jacketing other members of the BPP.

- Mass media influence. Following Hampton’s assassination, BPP members were depicted as “folk devils,” with media representations becoming increasingly distorted.

2. The legal system

Communist and Black Panther Party member and COINTELPRO target Angela Davis was charged with “aggravated kidnapping and first-degree murder” in the death of a judge in California who was kidnapped and killed during a melee with police, even though Davis was not on the scene. California held that the guns used by the kidnappers were owned by Davis and considered “all persons concerned in the commission of a crime, whether they directly commit the act constituting the offense . . . , principals in any crime so committed.” Davis could not be found at the time and was listed by J. Edgar Hoover on the FBI’s “Ten Most Wanted Fugitives” list. Months later, Davis was apprehended and spent sixteen months in prison awaiting a trial in which she was found not guilty.

3. Employment deprivation

Prior to Davis’s battle with the legal system, Davis was fired from her job as a philosophy professor at UCLA for her Communist Party membership in her first year of employment in 1969, called unsuitable to teach in the California system. The firing was at the request of then California governor Ronald Reagan, who pointed to a 1949 law outlawing the hiring of Communists in the University of California. This highlights the lingering Red Scare era or McCarthyism that ran through the 1940s and 1950s. The FBI supported the demonization of communism through a predecessor program to COINTELPRO: COMINFIL (Communist Infiltration) probed and tracked the activities of labor, social justice, and racial equality movements.

4. Conspicuous surveillance

Among the first round of FBI documents to come to light about COINTELPRO was a document memo called “New Left Notes.” The New Left refers to a broad political movement of the 1960s and 1970s, groups of which campaigned on social issues such as civil, political, women’s, gay, and abortion rights. In discussing how to deal with “New Left problems,” the FBI Philadelphia field office memo says, “There was a pretty general consensus that more interviews with these subjects and hangers-on are in order for plenty of reasons, chief of which are it will enhance the paranoia endemic in these circles and will further serve to get the point across [that] there is an FBI Agent behind every mailbox. In addition, some will be overcome by the overwhelming personalities of the contacting agent and volunteer to tell all—perhaps on a continuing basis.”

5. Covert surveillance

The Church Committee reported enumerated covert surveillance that “was not only vastly excessive in breadth . . . but also often conducted by illegal or improper means.” Notably, both the CIA and FBI had “mail-opening programs” that indiscriminately opened and photocopied letters mailed in the US on a vast scale: nearly a quarter of a million by the CIA between 1953 and 1973 and another 130,000 by the FBI from 1940 to 1966. Further, both the CIA and the FBI lied about the continuation of these programs to President Nixon.

6. Deception

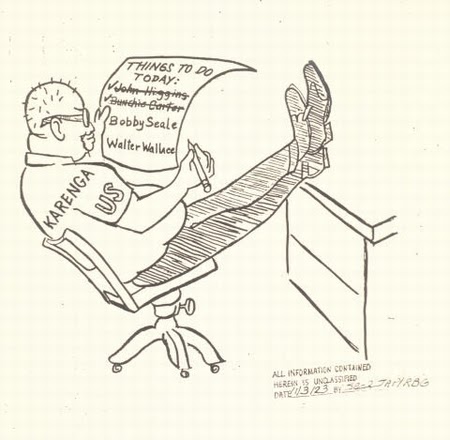

The FBI often sent fake letters or flyers in order to drive wedges between otherwise aligned groups. Below is an example of a cartoon drawn by FBI operatives as a forgery of movement participants and is intended to incite violence between the Black nationalist groups Organization Us (coestablished by Maulana Karenga) and the Black Panther Party (with prominent members Huey Newton, David Hilliard, Bobby Seale, John Huggins, and Bunchy Carter). The cartoon depicts BPP being knocked off by Karenga. The FBI later claimed success in the deaths of two BPP members by US gunmen.

7. Mass media influence

Manipulation of the mass media was an explicit tenet of the FBI’s COINTELPRO against the New Left. According to the Church Committee, “Much of the Bureau’s propaganda efforts involved giving information to ‘friendly’ media sources who could be relied upon not to reveal the Bureau’s interests. The Crime Records Division of the Bureau was responsible for public relations, including all headquarters contacts with the media. In the course of its work (most of which had nothing to do with COINTELPRO), the Division assembled a list of ‘friendly’ news media sources—those who wrote pro-Bureau stories. Field offices also had ‘confidential sources’ (unpaid Bureau informants) in the media, and were able to ensure their cooperation.”

What to Learn Next

External Resources

- Boykoff, Jules. Beyond Bullets: The Suppression of Dissent in the United States. AK, 2007. Oakland, CA.

- Wikipedia. “2019 Internet Blackout in Iran.” December 18, 2020.

- Shieber, Jonathan. “Zoom Admits to Shutting Down Activist Accounts at the Request of the Chinese Government.” TechCrunch, June 2020.

- Duane de la Vega, Kelly, and Katie Galloway. “Eric and ‘Anna.’” Field of Vision, November 19, 2015.

- US Senate Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities. Intelligence Activities and the Rights of Americans. Report No. 94-755. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1976.

- Churchill, Ward, and Jim Vander Wall. The COINTELPRO Papers: Documents from the FBI’s Secret Wars against Domestic Dissent. South End, 1990. Cambridge, MA.

Media Attributions

- things-to-do © Federal Bureau of Investigation is licensed under a Public Domain license